Liver diseases create a significant burden for our healthcare system due to their high prevalence and associated morbidity and mortality rates. For the last 30 years, hepatitis C has been seen as the leading cause of liver disease. Still, thanks to effective direct antiviral treatment and screening strategies, it now occupies a far less prominent position. Hepatitis B virus infection continues to affect almost 0.7% of the Spanish population. At the same time, alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) have become the main liver health problems in our area. There are biomarkers for viral hepatitis which are considered as the reference diagnostic tests: in the case of hepatitis C, detection of antibodies and HCV RNA; and in the case of hepatitis B, detection of the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and HBV DNA. In contrast, there are no diagnostic biomarkers for ALD and MAFLD. The main prognostic factor in both conditions has been found to be the stage of liver fibrosis. At present, therefore, the detection of occult prevalent liver diseases is based on the early identification of populations at risk of developing advanced fibrosis. The Spanish Triple A (AAA) framework can be used for suspected ALD: Anamnesis [medical history], Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test - Consumption (AUDIT-C) and Alcoholic Liver Disease/Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Index (ANI); while for suspected MAFLD, having any metabolic comorbidity will be taken into account, particularly obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2). In patients suspected of having MAFLD or ALD, even with persistently normal transaminases, non-invasive biochemical fibrosis assessment methods will be used, based on both routine clinical-analytical parameters and recorded scores, as well as imaging methods, in particular, transient elastography (TE) and shear wave elastography (Fig. 1).

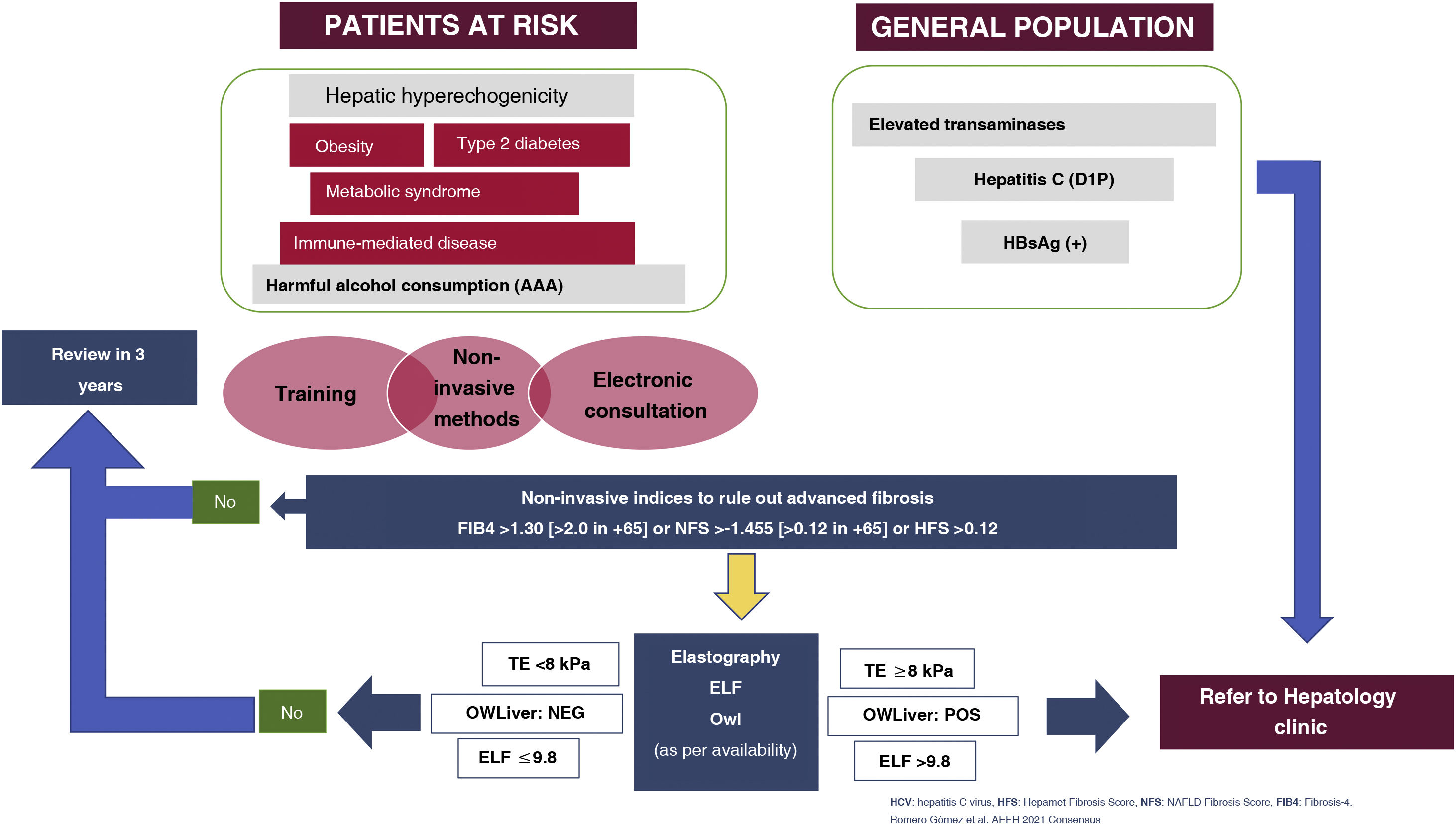

Algorithm for detection and referral of prevalent liver diseases (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol-related liver disease and metabolic fatty liver disease).

AAA: Anamnesis [medical history]; AUDIT, ANI; D1P: diagnóstico en un solo paso [one-step diagnosis]; ELF: European Liver Panel; TE: transient elastography; HFS: Hepamet Fibrosis Score; NFS: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Fibrosis Score.

The aim of this consensus is to define a set of Clinical Practice Guidelines to promote the detection of silent prevalent liver diseases, beyond the hepatology clinic, in primary care, endocrinology, nutrition and diabetes, cardiology, neurology and internal medicine clinics, as well as in clinics for inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatology and dermatology. In all these departments, the prevalence of liver disease creates an additional care burden which we must not underestimate, with it representing a major health problem. As a starting point, we provide the view of Spanish hepatology as a proposal for improving the detection and referral of the disease, with the aim of extending it to society as a whole once further consensus has been reached. We also need to establish circuits based on the training of healthcare professionals, availability of diagnostic tools and fluent communication with hepatology clinics to guarantee quality care, ultimately improving citizens' health (Table 1).

Result of the evaluation of the consensus recommendations by the members of the AEEH (n = 89).

| Question | Agree % | Disagree % | Neither agree nor disagree % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 92.1 | 3.4 | 4.5 |

| 2 | 78.7 | 3.4 | 16.9 |

| 3 | 96.6 | 1.1 | 2.2 |

| 4 | 93.3 | 1.1 | 5.6 |

| 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 84.3 | 2.2 | 12.4 |

| 8 | 78.7 | 5.6 | 15.7 |

| 9 | 85.4 | 0 | 12.4 |

| 10 | 77.5 | 3.4 | 19.1 |

| 11 | 92.1 | 2.2 | 5.6 |

| 12 | 93.3 | 0 | 6.7 |

| 13 | 67.4 | 9 | 22.5 |

| 14 | 78.7 | 15.7 | 5.6 |

| 15 | 95.5 | 1.1 | 2.2 |

| 16 | 57.3 | 13.5 | 21.3 |

| 17 | 58.4 | 14.6 | 24.7 |

| 18 | 65.2 | 7.9 | 22.5 |

| 19 | 83.1 | 3.4 | 13.5 |

The consensus has been drawn up under the auspices of the Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado (AEEH) [Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver], with the collaboration of a panel of Spanish experts. For the preparation of this document, we set up working groups to prepare different PICO (Population/problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) questions, which were first discussed and agreed on before finally proposing the degree of recommendation and level of evidence, which were then voted on using the Delphi method.

The aim of this document is to propose recommendations on the detection of occult prevalent diseases, such as MAFLD, ALD and viral hepatitis, and answer key questions for daily clinical practice. We have also aimed to respond to how best to approach the detection, monitoring and referral to hepatology of these prevalent liver diseases, in addition to promoting the detection and diagnosis of hepatitis C in at-risk populations, to meet the World Health Organisation (WHO) objective of eliminating hepatitis C by the year 2030.

The recommendations in this guideline have been established according to: level of evidence: A (high), B (moderate), C (low); and grade of recommendation: strong (1), weak (2). In addition, we have added the percentage of participants who endorsed each of the three answers to each question out of a team of hepatologists specially dedicated to clinical practice in prevalent liver diseases.

Question 1. Is the screening for and detection of silent liver disease in the general adult population here in Spain justified?Answer 1: Yes. There may be over a million people with significant liver fibrosis (F ≥ 2) here in Spain, one in six of them with cirrhosis. Patients at risk of advanced fibrosis, such as those with obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, metabolic syndrome (MetS) or harmful alcohol consumption, should be screened. Hepatitis B and C virus serology should be requested in all people over the age of 40.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

There are an estimated 165,000–188,000 patients with cirrhosis in Spain.1,2 Compared to the general population adjusted for gender and age, this population has more comorbidity and uses healthcare resources more frequently, including visits to clinics and hospitals.3 It is estimated that the prevalence of significant fibrosis in the Spanish population, assessed using TE ≥ 9 kPa, is 3.6%, representing approximately 1,180,000 patients. Population-based studies show that being male, having central obesity, DM-2, elevated triglyceride levels, low HDL-cholesterol and elevated alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase (AST/ALT) ratio are all independently associated with greater liver stiffness in patients with harmful alcohol consumption, patients with chronic viral hepatitis due to hepatitis B or C, and patients with MAFLD. Therefore, in view of the significant disease burden, the detection of prevalent liver diseases should be promoted.

Question 2. Is it cost-effective screen for and detect occult prevalent liver diseases in the general population?Answer 2: Yes. The detection of silent liver disease is beneficial in terms of cost-effectiveness in a scenario of low prevalence of cirrhosis as here in Spain, where MAFLD is the most prevalent aetiology.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

It is theoretically attractive to promote early detection of a potentially serious disease with serious complications such as cirrhosis. As with any proposal for population screening, the method used must be cost-effective and the detection of cases must result in an intervention which changes the natural course of the disease. Non-invasive methods (including TE) have proven to be cost-effective for liver fibrosis screening and especially useful in primary care.4 To date, there is no specific treatment to reverse advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, beyond the treatment of the aetiology. There is no question of the benefits of therapeutic intervention in chronic hepatitis B and C virus liver disease. In the most prevalent liver diseases, such as MAFLD and ALD, however, one might think that these benefits are not defined. In a recent study, through modelling, three scenarios were analysed of low, intermediate and high cirrhosis prevalence, 0.27%, 2%, and 4% respectively. They found that, in a low-prevalence scenario, fibrosis index 4 (FIB-4) followed by TE, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or liver biopsy are cost-effective strategies with high diagnostic accuracy. However, Fib-4 + TE is the cheapest and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of FIB-4 + MRI is lower than that of FIB-4 + liver biopsy.5

It should be highlighted that the detection of ALD opens the way for intervention to eliminate alcohol consumption.6 In fact, in patients with ALD, abstinence is the most decisive prognostic factor for survival.7 Moreover, patients with MAFLD and fibrosis are advised to start a regime of diet and physical exercise with the aim of losing weight; weight-loss improves liver disease, helping resolve fatty liver lesions and leading to regression of the fibrosis.8 A two-way relationship has been demonstrated between the progression of fibrosis in MAFLD and cardiovascular risk factors such as the development of DM2 and hypertension. Advanced fibrosis has also been independently associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events,9 while metabolic disorders promote fibrosis progression. Importantly, however, the control of comorbidities associated with MAFLD affects the natural history of the disease, both through reducing cardiovascular events and a potential reduction in the risk of liver cancer, linked to the preventive effect of drugs such as metformin and statins observed in population studies; all of which supports both the need for early detection and its potential cost-effectiveness.10–12

Question 3. Should public authorities be asked to cooperate more in the prevention of risk factors for prevalent liver disease?Answer 3: Yes, the government can legislate in a way which has a significant impact on prevalent liver disease. It can define the minimum price per unit of alcohol, modulate taxes to favour healthy diets, promote healthy lifestyle habits and design a programme to eliminate viral hepatitis.

Level of evidence: C

Grade of recommendation: 2

The most common reason for liver transplantation in the European Union is alcoholic liver disease.13 Some interventions, such as the introduction of the minimum price per unit, direct taxes on alcohol, or a combination of the two, have resulted in a decrease in alcohol-related deaths.14 To be globally effective, this intervention does not require population screening, but it is not enough in itself. The implementation of policies encouraging a balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle through the promotion of physical exercise, such as cycle lanes, pedestrian, recreational and sports zones, providing incentives for using public transport, taxing sugary drinks and saturated fats, and reducing the VAT on the components of the Mediterranean diet can help boost health overall and specifically reduce the incidence of MAFLD.15

In addition, the involvement and effort of public authorities in the elimination of hepatitis C has made Spain one of the leading countries in terms of progress in achieving the WHO global strategy objectives for viral hepatitis ceasing to be a public health problem by 2030. The pursuit of this target has involved a large number of recommendations being put into practice, grouped into five broad categories: 1) age-group screening for hepatitis C; 2) simplifying diagnosis (one-step diagnosis and diagnosis at the patient's point of care); 3) simplifying treatment and improving care circuits; 4) health policy measures; and, finally 5) establishing hepatitis elimination indicators as included in the AEEH Guidelines on the elimination of hepatitis C.16

Question 4. Should the active search for and detection of occult prevalent liver disease be carried out mainly in primary care?Answer 4: Yes. Primary care is the ideal scenario to promote the active search for and detection of patients with liver disease, as it is the entry point to the healthcare system and the clinical setting for managing patients at risk.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

Primary care is the ideal space to actively find patients at risk of liver fibrosis, particularly in patients with harmful alcohol consumption, with MetS, obesity and diabetes, and patients at risk of viral hepatitis. In these at-risk populations3 screening for liver fibrosis should be promoted using non-invasive biochemical indices, elastography or the study of hepatitis B and C serology, as well as one-step diagnosis.17

Many algorithms have tried to use serological markers sequentially to be able to identify patients with MAFLD and fibrosis in primary care.18 In patients with suspected MAFLD, non-invasive studies using liver fibrosis indices such as FIB-4, Hepamet Fibrosis Score (HFS) or Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Score (NFS) to detect fibrosis are all recommended.19 In the case of hepatitis C, one-step diagnosis is recommended, meaning detection of anti-HCV antibodies and measurement of the viral load in those who are positive with a single blood sample. For hepatitis B, HBsAg should be requested. Lastly, harmful alcohol consumption must be ruled out through the AAA (Anamnesis [medical history], AUDIT-C and ANI).

Question 5. Is it clinically sufficient to detect advanced liver fibrosis by non-invasive biochemical methods in occult prevalent liver diseases such as MAFLD and ALD?Answer 5: Yes, for screening, the detection of data suggesting advanced fibrosis in prevalent liver disease may be the most appropriate criteria for decision-making in MAFLD and ALD. In viral hepatitis, serology and viral load will also be investigated.

Level of evidence: A

Grade of recommendation: 1

Prevalent liver diseases are divided into two groups: viral and non-viral. In the most prevalent viral diseases, such as hepatitis B or C, detection of fibrosis by biochemical methods is useful, but serological markers of viral infection, such as serology and viral load quantification, are the methods of choice for finding and detecting viral hepatitis.20,21 In the case of non-viral diseases (MAFLD and ALD), the assessment of fibrosis using biochemical methods is considered the most appropriate screening option, as fibrosis is the main prognostic factor and the therapeutic target.22 Patients with suspected advanced fibrosis should also be referred to a hepatologist, in order to confirm diagnosis and plan therapy and follow-up.23 In addition to assessing the fibrosis, a more in-depth investigation of the possible metabolic diseases involved in the development of MAFLD is necessary, in order to better control the liver disease.24

Question 6. Are the prevalence of MAFLD and associated morbidity rate increased in patients with diabetes?Answer 6: yes. The prevalence and severity of MAFLD are greater in patients with diabetes.

Level of evidence: A

Grade of recommendation: 1

The prevalence of MAFLD increases at the same rate as the prevalence of MetS, obesity and DM2.25 Among patients with DM2, the prevalence of MAFLD is estimated at 40%–70%, and the prevalence of fatty liver disease at 22%.26 The prevalence of DM2 in Spain is 13.8%, so DM2-related fatty liver disease is estimated to affect over 2.5% of the Spanish population.

Moreover, the insulin resistance in these patients with DM2 is related to liver fibrosis (odds ratio [OR]: 1.53: 95% CI: 1.1–2.2; P = .026).27 The early detection and diagnosis of MAFLD and fibrosis in patients with DM2 could improve their prognosis. In most previous studies, patients with MAFLD and DM2 tended to have advanced fibrosis.28 A recent meta-analysis showed that DM2 is related to a higher incidence of serious liver events (cirrhosis, complications and death) (HR: 2.25; 95% CI: 1.83–2.76; P < .001). That study, which assessed data from 12 papers, with 22.8 million patients followed up for 10 years (IQR: 6.4–16.9), also demonstrated that obesity has an influence, although with a lower HR. The application of non-invasive indices to patients with DM2, sequentially using the fatty liver index (FLI) and fibrosis indices such as the FIB-4 index, would lead to hepatology clinic referral in 13.4% of patients. It was also shown that 10% of patients with DM2 had a TE > 10 kPa and that 5% had liver biopsy findings of advanced fibrosis, so checking for liver fibrosis is mandatory in this at-risk population.29

Question 7. Should patients with immune-mediated skin diseases be checked for liver disease?Answer 7: Yes. Patients with immune-mediated skin diseases should be assessed and monitored for possible chronic liver disease.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

The prevalence of chronic liver disease and, specifically, MAFLD is higher in patients with immune-mediated diseases and, very particularly, in skin diseases such as psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa. Psoriasis is a chronic disease which has often been linked to MetS factors. The prevalence and severity of MAFLD is significantly higher in patients with psoriasis.30 Similarly, patients with psoriasis and MAFLD are more likely to have MetS and more severe psoriasis (even with joint involvement).31 The factors associated with MAFLD are: waist circumference; psoriasis activity and severity index (PASI); transaminase abnormalities; hypertension; and smoking.32 Therefore, all patients with psoriasis should be screened for MAFLD. A lack of liver damage on the first occasion does not mean it will not develop over the years. Periodic assessment of liver function using non-invasive fibrosis detection methods is therefore indicated in these patients.33 A recent position paper recommends that transient elastography be considered as a routine investigation in monitoring methotrexate treatment, repeated every three years if kPa < 7.5 and annually if kPa > 7.5. Liver biopsy should be considered in patients with kPa > 9.5.34 Lastly, patients with hidradenitis suppurativa also have a higher prevalence of MAFLD, regardless of metabolic risk factors,35 so this subgroup of patients should also be screened.

Question 8. Should chronic liver disease be tested for in patients with inflammatory bowel disease?Answer 8: Yes, chronic liver disease and specifically MAFLD is more prevalent in patients with IBD and may have a negative impact on their prognosis.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

MAFLD is the most common cause of elevated transaminases in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In a meta-analysis designed to determine the prevalence of MAFLD among patients with IBD and to identify possible associated risk factors in this subgroup of patients, an overall prevalence of 32% was found, although with great heterogeneity.36 In fact, most studies used abdominal ultrasound to diagnose MAFLD, which is known to have limited accuracy. Some studies have shown that increased body mass index is the most important predictor of significant fibrosis. MAFLD is associated with a high degree of morbidity in IBD, and in hospitalised patients it leads to mortality rates twice those of patients who only have IBD.37 MAFLD is known to increase the risk of drug-induced liver toxicity and vice versa. The factors associated with MAFLD among patients with IBD are: older age and higher body mass index; presence of DM2; duration of IBD; and previous history of bowel resection. In view of the high prevalence of MAFLD among patients with IBD, liver disease screening should be performed in patients with these comorbidities (in addition to other MAFLD components),38 and patients treated with drugs which increase the risk of developing of fatty liver disease. Abdominal ultrasound and non-invasive markers such as FLI have been proposed for this. Some studies have suggested using TE in conjunction with measurement of the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). In patients with evidence of fatty liver disease, advanced fibrosis must be ruled out. If this is ruled out, the patient should be reassessed periodically (every 2–3 years) and if advanced fibrosis is diagnosed, IBD patients should be referred to a hepatologist.39

Question 9. Is the frequency of chronic liver disease increased in diseases with inflammatory or immunological pathogenesis?Answer 9: Yes, the prevalence of chronic liver disease is increased in these diseases both by immunological and inflammatory mechanisms and due to hepatotoxicity.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

Impaired liver function occurs in up to 60% of diseases of inflammatory or immunological origin and is caused by both immunological and inflammatory mechanisms as well as drug toxicity. In most cases, the impairment is acute and becomes apparent with an increase in transaminases, being secondary to hepatotoxicity or the inflammatory activity of the disease itself. Chronic liver disease can occur in up to 30% of rheumatic diseases of immunological origin,40 such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis41 and Sjögren's syndrome.42 In this context, the pathogenesis of the liver disease may be autoimmune (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis), viral (HCV) or metabolic (MAFLD), in variable proportions according to each type of disease. In relation to systemic vasculitis, HCV and HBV infection are associated with cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis, and HBV infection, with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). The incidence of MAFLD is particularly high in rheumatoid arthritis, where the risk is doubled, and in non-immunological rheumatic diseases such as gout and fibromyalgia.43

Question 10. Should patients with severe mental illness be investigated for prevalent liver disease?Answer 10: Yes. Patients with severe mental illness should be assessed and monitored for possible chronic liver disease, whether alcohol-related, metabolic or due to hepatitis C.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

Severe mental illness (SMI) refers to “a heterogeneous group of people who suffer from severe psychiatric illnesses which cause long-lasting mental disorders with varying degrees of disability and social dysfunction, and who need to be supported using a variety of social and healthcare resources from the psychiatric and social care network”. Patients with psycho-affective disorders have been found to have an increased prevalence of hepatitis C,44 as well as a marked increase in the likelihood of developing MAFLD.45 However, comorbidities and the use of potentially hepatotoxic drugs are common in these patients. Therefore, screening for hepatitis C, MAFLD and ALD is recommended in patients with severe mental illness.

Question 11. Are biochemical methods based on non-invasive clinical-analytical indices useful in detecting fatty-liver-disease-related occult prevalent liver diseases?Answer 11: Yes. There are simple, validated biochemical methods which enable us to determine which patients have fatty liver disease and whether it may be associated with metabolic disorder or alcohol consumption.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 1

Chronic liver disease can be detected using reliable, validated biochemical methods (non-invasive indices based on clinical-analytical variables).46 There are at least five indices which enable diagnosis of fatty liver disease: FLI; triglyceride-glucose index (TyG); hepatic steatosis index (HSI); NFS; and the visceral adiposity index (VAI) (the first four can be calculated at https://www.mdapp.co/hepatology/). These methods use clinical parameters (gender, body mass index, waist circumference, MetS, DM2) and/or analytical parameters (triglycerides, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), insulin, transaminases, blood glucose). Diagnostic reliability is satisfactory with areas under the curve of 0.80−0.92, with a high positive predictive value (99%) and acceptable sensitivity (61%–80%).47 Their main limitation lies in their inability to distinguish between different degrees of steatosis. In patients with fatty liver disease, we need to know whether the cause is metabolic or alcohol-related. In the case of steatosis, the ANI is highly reliable in distinguishing whether the origin is alcohol-related or metabolic.48 Its variables are also simple (weight, height, gender, transaminases and mean corpuscular volume) and are easily calculable (Appendix Bannex I). The results are valid even after six months of abstinence. A negative score makes an alcohol-related origin unlikely, but a positive result does not rule out associated metabolic syndrome. The steatosis markers used alongside the biochemical fibrosis tests are useful in determining the metabolic origin of liver involvement in screening strategies. At the same time, AUDIT and ANI define the relevance of alcohol in liver disease.

Question 12. Is the diagnostic performance of the non-invasive clinical-analytical indices for the detection of liver fibrosis different in occult prevalent liver diseases of different aetiologies?Answer 12: Yes, the methods achieve better results in the diseases for which they were developed. HFS is superior to FIB-4 in the detection of MAFLD. FIB-4 is an excellent method in viral hepatitis. In ALD these methods have not been sufficiently validated.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

The FibroTest, FIB-4 and APRI have been studied in general population, showing a prevalence of fibrosis ≥ F2 of 2.8% and of cirrhosis of 0.3%–1.4%.49 Most of the non-invasive indices for the detection of fibrosis (FIB-4, Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet-ratio index [APRI], FibroTest, Enhanced Liver Fibrosis [ELF], Fibrometer), although developed for hepatitis C, have been validated in other chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B, ALD and MAFLD. In general, all of them impress for their reliability in the detection of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis (areas under the curve 0.800.94) and high negative predictive value (>90%).50 For hepatitis B, the APRI, ELF and FIB-4 have limited diagnostic capacity to detect significant fibrosis and do not reflect changes in fibrosis very well.51 With FIB-4 < 1.45 or APRI < 0.5, significant fibrosis can be ruled out with an area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) of 0.78 and 0.74 respectively, which is a less than ideal predictive capacity (AUROC from 0.85). In viral hepatitis, the indices such as ELF, FibroTest, Fibrometer and Fibroscore, which are all patented, have to paid for and are less accessible, and do not make up for the slightly better results they offer compared to the free indices.52

The NFS and HFS indices were developed specifically for MAFLD· In the population of MAFLD patients at risk of advanced fibrosis, the best results are obtained with HFS6 (https://www.hepamet-fibrosis-score.eu/, annex I), with an area under the curve in the detection of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis of 0.85, higher than FIB-4 and NFS (0.80), and fewer patients with indeterminate results (20% vs 30%).53 The combined use of HFS, NFS and FIB-4 enables the correct exclusion of patients without advanced fibrosis, which is why they are the methods of choice in primary care or in non-hepatology clinics. Patients in the grey area (combined index > 0 but <3, in other words with one or two methods abnormal) may benefit from a second non-invasive method such as ELF or OWLiver, which would help define which patients are at risk of advanced fibrosis. Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) is a method based on the determination of the levels of hyaluronic acid (HA), amino-terminal peptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP) and the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I (TIMP-1). Its use as a second test after FIB-4 reduced the referral rate to less than 20% and multiplied the cases referred with advanced fibrosis by five.54 Alternatively, OWLiver has shown a sensitivity of 63.3% and a specificity of 75.4% in the validation study in the NIMBLE cohort.55

In the detection of ALD advanced fibrosis, the indices that have to be paid for are superior to the free ones, with areas under the curve for FibroTest, Fibrometer and Hepascore of 0.83 for fibrosis ≥ F2 and 0.92–94 for cirrhosis, and of only 0.70 and 0.80 respectively with FIB-4.

Question 13. Do non-invasive methods make it possible to detect steatohepatitis in MAFLD?Answer 13: Yes, Owl-liver has shown capacity to diagnose steatohepatitis in patients with MAFLD. Routine non-invasive biochemical methods enable the presence of steatosis and/or fibrosis to be detected, but are sub-optimal in the detection of steatohepatitis. DeMILI's NASH-MRI is the imaging biomarker which can detect the presence of steatohepatitis.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 1

Non-invasive detection of metabolic steatohepatitis is an unmet need, as results have not been robust enough to date to displace liver biopsy. Methods including epidemiological, anthropometric and biochemical variables such as FIB-4, HFS and NFS have AUROC below 0.7 for the diagnosis of steatohepatitis. Cell death biomarkers such as CK1856 have provided results, but they are not used in routine clinical practice. Methods based on lipidomics57 such as OWLiver®58 have shown excellent AUROC in diagnosing steatohepatitis compared to biopsy, especially in populations with diabetes and obesity. Imaging biomarkers based on magnetic resonance imaging such as DeMILI (NASH-MRI) have similarly reported promising results.59 However, the gold standard in the diagnosis of steatohepatitis continues to be liver biopsy.

Question 14. Does conventional abdominal ultrasound have sufficient diagnostic accuracy (compared to other non-invasive diagnostic methods) for early detection of occult chronic liver disease in the general adult population?Answer 14: No. The sensitivity of ultrasound for detection of significant fibrosis is suboptimal.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 1

Abdominal ultrasound is part of the assessment of all patients with elevated transaminases or suspected liver disease, but it has limited diagnostic accuracy in detecting liver fibrosis. Its specificity is excellent (>90%) in the presence of signs of portal hypertension (intra-abdominal collateral circulation, splenomegaly) and/or liver surface nodularity, even in compensated patients.60 However, unlike other imaging techniques such as transient elastography, its sensitivity in detecting cirrhosis or significant fibrosis is suboptimal (<50%), which limits its utility in early detection programmes for fibrosis associated with prevalent liver disease.61

Question 15. From a practical point of view, can we assume the absence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in adults from the general population with transient elastography < 8 kPa?Answer 15: Yes. The 8 kPa threshold has shown a high negative predictive value for excluding cirrhosis in diagnostic studies and a low risk of liver events in longitudinal studies.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 1

TE (measured with FibroScan®) has proved to be very useful diagnostically in predicting advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis. When liver biopsy is used as the reference standard, TE provides high sensitivity and negative predictive values of over 95% for the detection of cirrhosis, for a wide range of prevalences and aetiologies of underlying liver disease, making it more useful for ruling out cirrhosis rather than for confirming it.62 The recommended TE cut-off points to rule out advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis vary from 8 to 13 kPa, depending on the underlying aetiology.63 It should be noted that the medium-term risk of liver events in patients with TE below these thresholds is very low (for the example of MAFLD, the 5-year risk of liver event with FibroScan® < 12 kPa is 0.3%).64 Based on the above, it seems prudent to generally adopt the value of TE < 8 kPa to rule out advanced fibrosis and TE < 10 kPa to rule out compensated cirrhosis, given its transferability between aetiologies, the low false negative rate and the practically zero incidence of liver events in the medium term.

Question 16. Are elastographic methods incorporated into general ultrasound equipment (Shear Wave Elastography [SWE] and Acoustic Radiation Force Imaging [ARFI]) valid compared to TE by FibroScan® for the detection of occult prevalent liver disease?Answer 16: No. Further epidemiological and follow-up studies are needed using these techniques, and their cut-off points need to be defined.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 1

The main theoretical advantages of these techniques (which are incorporated into conventional ultrasound devices) compared to TE by FibroScan® are the higher success rate in obese patients and the ability to assess liver morphology in the same examination. In general terms, and as with TE, these techniques have high sensitivity and negative predictive value to rule out the presence of cirrhosis, but less than ideal specificity and positive predictive value to confirm it.65 In the latest European guidelines, the suggested cut-off point for the diagnosis of cirrhosis was 1.8–1.9 m/s for ARFI and 10.1 kPa for SWE.66 In comparative studies between FibroScan®, ARFI and SWE, diagnostic performance was generally found to be similar. The main disadvantage in the use of these techniques (SWE, ARFI) is the limited number of epidemiological validation studies of the cut-off points and long-term clinical follow-up studies, which limits confidence in the safety of these values for use in large-scale early detection programmes.

Question 17. Should access to liver TE be guaranteed before referring the patient to hepatology?Answer 17: Yes, as long as it is carried out by accredited personnel, under optimal conditions and in conjunction with non-invasive biochemical tests. The sequential combinations of HFS and FibroScan® and FIB-4 and FibroScan® have shown high diagnostic performance.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

Primary care physicians and other specialities routinely request a liver profile with transaminases to check for liver disease. However, ALT and AST levels do not, in isolation, relate to the stage of fibrosis. A recent systematic review showed that 90% of patients with cirrhosis would not have been diagnosed using the usual liver profile tests.67 There are some clinical practice guidelines which recommend performing TE using FibroScan® in men and women with alcohol consumption greater than 50 and 35 units per week respectively.68 The specificity in this population for the diagnosis of cirrhosis is 95%, with a cut-off point of 14.6 kPa.69 In addition, TE has been shown to be cost-effective in primary care.4

Recent data suggest that the combinations of HFS and TE in Europe and FIB-4 and TE in the USA are the most cost-effective strategies in identifying patients with cirrhosis in the MAFLD population, showing high diagnostic accuracy (89.3%, 88.5% and 87.5% respectively, for an estimated prevalence of 0.27%, 2% and 4%). At the same time, the combination of the NFS index and TE has been shown to be cost-effective in the assessment of patients with MAFLD, both in Europe70 and in the USA.71

Question 18. Should access to proprietary non-invasive methods be guaranteed to confirm suspected advanced fibrosis in the event that transient elastography cannot be accessed?Answer 18: Yes, methods such as ELF have proven to be cost-effective as a second-line method in the selection of patients to be referred when there is no access to FibroScan®.

Level of evidence: B

Grade of recommendation: 2

Despite the limited cost-effectiveness data on screening for this disease, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends confirming the presence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with MAFLD using non-invasive tests, especially in patients with risk factors such as diabetes, being over the age of 50, obesity and MetS. The European guidelines on the management of MAFLD recommends that some non-invasive test should be used in the initial assessment of fibrosis in all patients with MAFLD, and place methods requiring payment such as ELF and FibroTest at the same diagnostic level as NFS and FIB-4 (EASL CPG). Although non-proprietary biochemical diagnostic methods such as FIB-4 and NFS have lower diagnostic accuracy, their low cost and easy accessibility have made them the most widely used in daily clinical practice. The inclusion of ELF sequentially after routine methods (FIB-4) in the algorithms for referral of patients with MAFLD from primary to specialised in the United Kingdom has been shown to be cost-effective.72 The utility of ELF has also been reported in the stratification of patients with a higher risk of progression and development of liver events in the future.73

Question 19. Is the detection and referral of patients with occult prevalent liver disease indicated in a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic situation?Answer 19: Yes, screening for diseases which may endanger a patient’s life and reduce their quality of life cannot be interrupted due to the emergence of other diseases.

Level of evidence: C

Grade of recommendation: 2

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, far from being a barrier, can be an opportunity for detecting occult prevalent liver diseases. Hepatitis B and C can be detected in the context of vaccination, for example when checking the antibody response. MAFLD should be checked for in all patients admitted for COVID-19, as it has been associated with worse outcomes.74 Elevated baseline FIB-4 levels impact the prognosis, clinical outcome and survival of patients with severe COVID-19 requiring hospital admission.75,76 Abnormal liver function tests, such as for AST, ALT and bilirubin, and liver cirrhosis are also independent predictors of mortality.77,78 Lastly, MAFLD should be checked for in all patients with an underlying metabolic or inflammatory component, whether chronic or acute immune-mediated, as occurs in SARS-CoV-2 infection.79

Conclusions- a)

Active testing for and detection of occult viral hepatitis in the general population is justified, cost-effective, endorsed by the institutions, and should be carried out in primary care.

- b)

In the case of metabolic fatty liver disease, the aim is to detect fibrosis in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic disorders and immune-mediated diseases, and in people with severe mental illness.

- c)

Non-invasive biochemical methods such as FIB-4, NFS and HFS in MAFLD, and the AAA in alcohol-related liver disease and serological determinations (One-step test for HBsAg and anti-HCV antibodies/HVC RNA) in viral hepatitis, form the frontline in the detection of prevalent liver disease.

- d)

Two-step detection combining non-invasive biochemical methods with transient elastography is the algorithm of choice. If that it is not available, ELF or OWLiver can be used in the same laboratory or substitute transient elastography with point or two-dimensional shear wave elastography.

- e)

In view of the impact of liver disease on the prognosis of COVID-19, the pandemic has increased the need for screening for prevalent liver diseases.

Manuel Romero Gómez declares paid consulting with: Abbvie, Alpha-sigma, Allergan, Astra-Zeneca, Axcella, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, Intercept, Inventia, Kaleido, MSD, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Prosciento, Rubió, Siemens, Shionogi, Sobi and Zydus. Research grants: Gilead, Intercept, Siemens. Inventor: Hepamet Fibrosis Score and DeMILI®.

José Luis Calleja declares paid consulting with: Intercept, Gilead Sciences, MSD and Echosens.

Sonia Alonso López declares paid consulting for Abbvie and Gilead and lectures for Abbvie and Gilead.

Conrado Fernandez Rodriguez declares paid consulting for Abbvie, Gilead and Intercept Pharma and research grants from Gilead and Intercept Pharma.

Javier Ampuero: Registration of the intellectual property of Hepamet Fibrosis Score.

Rocío Aller, Javier Crespo, Javier Rivera, Marta Hernández: Nothing to declare.

Work carried out with the support of the Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado (AEEH) [Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver]. No specific funding was received.

![Algorithm for detection and referral of prevalent liver diseases (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol-related liver disease and metabolic fatty liver disease). AAA: Anamnesis [medical history]; AUDIT, ANI; D1P: diagnóstico en un solo paso [one-step diagnosis]; ELF: European Liver Panel; TE: transient elastography; HFS: Hepamet Fibrosis Score; NFS: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Fibrosis Score. Algorithm for detection and referral of prevalent liver diseases (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol-related liver disease and metabolic fatty liver disease). AAA: Anamnesis [medical history]; AUDIT, ANI; D1P: diagnóstico en un solo paso [one-step diagnosis]; ELF: European Liver Panel; TE: transient elastography; HFS: Hepamet Fibrosis Score; NFS: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Fibrosis Score.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000004600000003/v1_202304191435/S2444382423000433/v1_202304191435/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)