We all recognize the Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection as the main cause of gastric cancer (GC), mainly adenocarcinomas. While its association with tubular (intestinal) type adenocarcinoma is well-established, it also plays an important role in the development of poorly cohesive (diffuse) type GC.1 In both cases, the presence of chronic inflammatory environment and gastric atrophy produced by Hp provides the substrate for the emergence of more advanced premalignant lesions, such as intestinal metaplasia (IM) and dysplasia, ultimately leading to adenocarcinoma.2 Currently, there is no doubt about the carcinogenic risk of gastric dysplasia (annual risk ranging from 0.6% to 6%), which is much lower for IM (0.25%) or gastric atrophy (0.1%).3 However, a subgroup of patients with atrophy or IM are at higher risk for GC, but the high-risk criteria for these patients have evolved and changed over time. For this purpose, the Young Group by the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) has considered to release this new section with a brief review of the history and a summary of current recommendations by different scientific societies about the identification and surveillance of patients with chronic atrophic gastritis at higher risk for GC. This story began in Sydney!

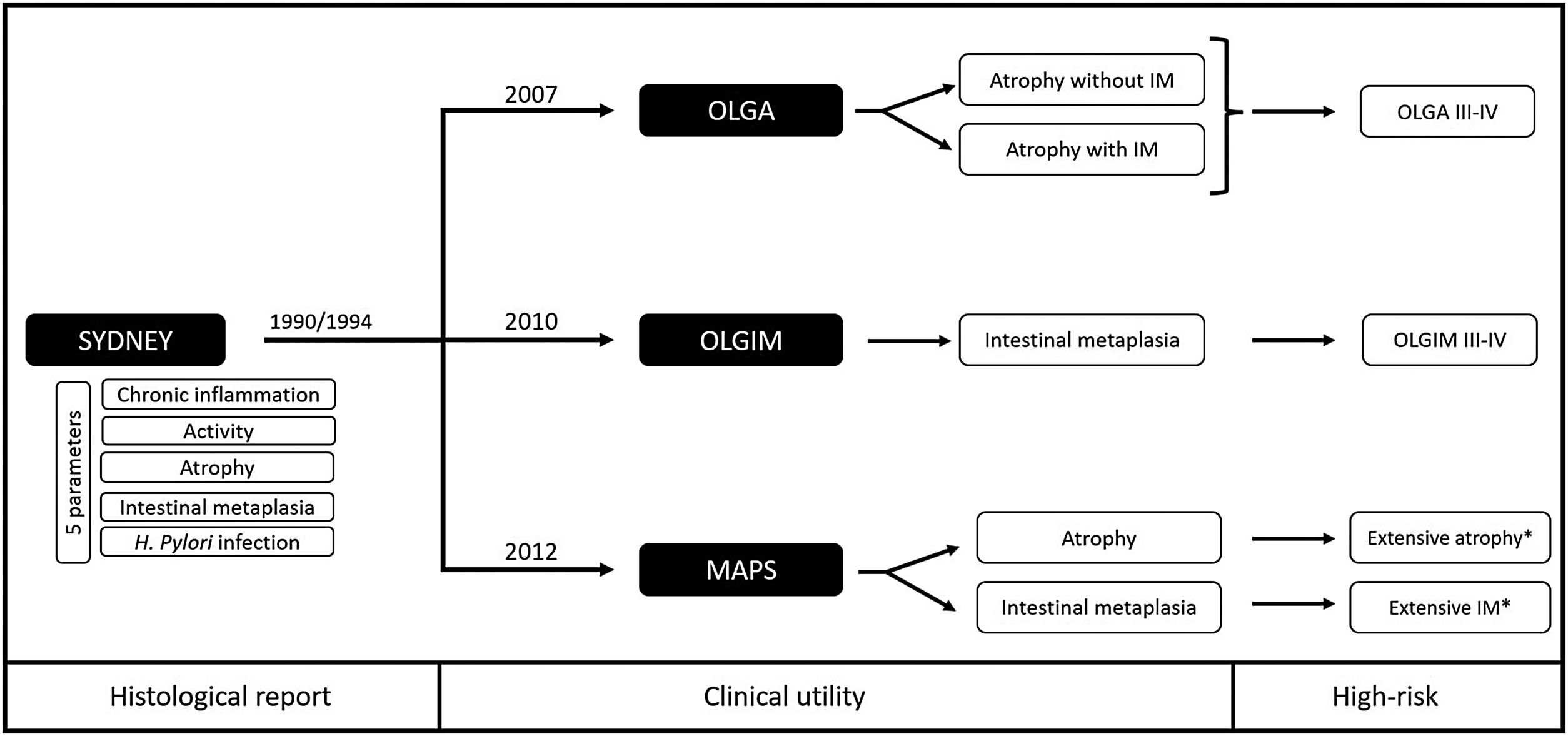

Sydney Consensus (first and updated version)In 1990, the first Sydney Consensus meant a step forward for the standardization of gastritis suggesting the histological report in terms of aetiology, topography, and morphology. This consensus established the histological examination of the distal gastric compartment (antrum) separately from the proximal one (corpus).4,5 In the updated consensus (1994) biopsies taken from the lesser and greater curvature of both the antrum and the body are recommended, and adding a biopsy from the middle part of the incisura together with those from the antrum. In each biopsy, the severity of the following five parameters should be reported: (i) chronic inflammation, (ii) activity, (iii) atrophy (loss of glands), (iv) intestinal metaplasia, and (v) presence of Hp. The severity of each parameter should be quantified based on a visual analogue scale in mild, moderate, and marked.6 Despite this significant step in standardizing the histological reporting of gastritis, this information does not have a clinical utility in predicting the GC risk.

OLGA (Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment)In 2007, the OLGA system was proposed to translate the histological information from the updated Sydney Consensus into clinically useful information. Based on the combined assessment of atrophy and IM observed in both the distal and proximal compartments, patients can be categorized into five stages (0, I, II, III, and IV).7 This way of determining severity has demonstrated its importance in predicting the GC risk. Patients in stages III and IV are considered to be at high risk.8 However, the main criticism of this classification is the moderate concordance in assessing gastric atrophy reported among pathologists. In addition, atrophy reproducibility also depends on the orientation of the biopsies, being more reproducible in the body than in the antrum/incisura.9

OLGIM (Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment)In the same line, the OLGIM system (2010) was proposed to stratify the risk of GC assessing only IM. This classification proved to be simpler and showed better agreement among pathologists compared to OLGA.10 Since IM goes one step further in the multistep histological model for GC development, in which atrophy precedes IM, the OLGIM system was proposed as an improvement in the patient's risk assessment. However, this new proposal led to a misunderstanding regarding the OLGA score. OLGA is not solely the assessment of atrophy (understood as gland loss), as it is explained in the next section.

OLGA vs OLGIMPreviously, in 2002, the OLGA research group highlighted a concept briefly mentioned in the initial Sydney Consensus: metaplastic changes occur at the expense of the loss of normal gastric glands and is invariably associated with atrophy.4 This group redefined the concept of chronic atrophic gastritis, in which atrophy can be of two types: (a) atrophy (gland loss) without metaplasia, and (b) atrophy (functional loss) with metaplasia (complete or incomplete, including pseudo-pyloric metaplasia). The practical utility of this redefinition of chronic atrophic gastritis is hindered by the complexity of the mathematical calculations that the pathologist must perform to subsequently obtain the OLGA score.11 A tutorial for OLGA was published to ensure its proper understanding and use by other pathologists.12 On the other hand, the OLGIM score, by evaluating only a fraction of the components of the OLGA, may underestimate the true risk in some patients with atrophy but without IM.13,14 Nevertheless, the OLGIM system emerged from the need to simplify the complexity of the different calculations proposed by OLGA. If the severity of IM is informed in the histological report, the OLGIM stage can be performed by any clinician in their practice, whereas the OLGA stage must be provided by the pathologist (since it represents a combined assessment of atrophy in its two variants – atrophy with and without IM).12

MAPS (management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach)In 2012, the European MAPS guideline proposed a simpler risk concept. This consensus suggested identifying patients based on the extent of atrophy or IM into two groups: low risk if it is limited (to the antrum±incisura) and high risk if it is extensive [antrum (± incisura)+body] but clinically significant (from moderate to marked).15,16 This simplification also has its weaknesses, and some high-risk patients may not be properly identified.17 In this regard, the guideline suggests to assess other factors that help correctly identify high-risk patients (see below).

Scientific societies and current recommendationsCurrently, the updated Sydney Consensus remains valid in both endoscopic (biopsy protocol) and histological recommendations (assessment of the five parameters). Since then, three systems have been proposed to translate this information into clinical practice, considering higher risk conditions: OLGA III/IV, OLGIM III/IV and extensive clinically significant atrophy or IM (Fig. 1).

Proposals to assess histological risk based on the Sydney Consensus. OLGA: Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment; OLGIM: Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment; MAPS: Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach; IM: intestinal metaplasia; *Clinically significant (moderate to marked) in both antrum/incisura and corpus.

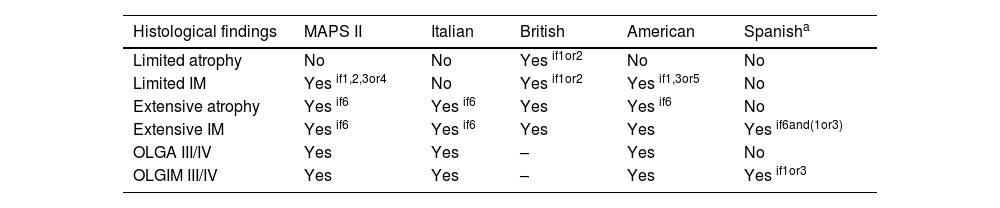

The assessment of gastric chronic atrophy and the GC risk requires a high-quality histological report considering not only the severity of atrophy and IM but also the IM subtype.16,18–21 However, in clinical practice incomplete IM could be not detected due to biopsy sampling error, and other risk factors should be assessed before excluding a patient with IM from endoscopic surveillance16,18,22 (Table 1). Considering these drawbacks in clinical practice, the British Society of Gastroenterology agrees considering high-risk conditions the extensive distribution of atrophy/IM regardless their severity or IM subtype.18

Surveillance recommendations according to different scientific societies.

| Histological findings | MAPS II | Italian | British | American | Spanisha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited atrophy | No | No | Yes if1or2 | No | No |

| Limited IM | Yes if1,2,3or4 | No | Yes if1or2 | Yes if1,3or5 | No |

| Extensive atrophy | Yes if6 | Yes if6 | Yes | Yes if6 | No |

| Extensive IM | Yes if6 | Yes if6 | Yes | Yes | Yes if6and(1or3) |

| OLGA III/IV | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | No |

| OLGIM III/IV | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes if1or3 |

1Family history of GC; 2Persistent Hp infection; 3Incomplete IM; 4Presence of autoimmune gastritis; 5High-risk ethnicity or immigrants from high-incidence regions (such as Asians and Latin Americans); 6Clinically significant (moderate to marked); GC: gastric cancer; IM: Intestinal Metaplasia; Hp: Helicobacter pylori.

Taking guided biopsies from areas of atrophy and IM during gastroscopy can significatively contribute to reduce the sampling error and get a better risk stratification.16,19,23 For this purpose, endoscopists should be familiar with endoscopic findings of atrophy and IM.24,25 Endoscopic classifications for atrophy (Kimura–Takemoto) and IM (EGGIM – Endoscopic Grading of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia) have proved their value showing a good concordance with histology among experts and being related with the presence and future development of GC.26–29 Furthermore, the regular arrangement of collecting venules in the body indicates a normal proximal gastric mucosa and the absence of Hp infection (if this pattern is also found in the distal part of the lesser curvature near incisura).30 Although high-definition imaging and virtual chromoendoscopy have shown to improve the recognition of these findings, the evidence that support the routine use of endoscopic classifications in western countries is limited.31

Kimura–Takemoto classificationThis classification is based on the identification of the pyloric and fundic gland transition (the so-called atrophic border). Atrophy is characterized by a yellowish pale colour and increased visibility of vessels in the mucosa.32 The atrophic border reflects the progression of atrophy from the distal to the proximal part of the stomach and is associated with the progression of the Hp infection (this fact explains why the regular arrangement of collecting venules is first affected in the distal part of the lesser curvature of the body).33 This classification has two important groups, the close (C) and open (O) types.32 The close type ranges from the absence of atrophic border (C0) to its presence in the antrum/incisura (C1) or to the lesser curvature of the body which could include its distal part (C2) to its proximal part (C3). The open type affects the whole lesser curvature of the body including the cardia (O1), progressing to the anterior/posterior wall (O2) and reaching to the greater curvature of the body (O3).25 Different studies have reported an increased risk for GC in patients from C3 to O3 type.26

EGGIM classificationThis classification has been prospectively validated and is based on the simplified NBI classification in which IM is characterized by a regular tubulo-villous pattern and the presence of the Light Blue Crest sign.27,34 Additional endoscopic findings for IM have been described and might be used for its estimation.24 The EGGIM classification assesses the absence (0 points) or presence of IM (1 point if <30% or 2 points if >30%) in five gastric areas: the lesser and greater curvature of the antrum, the incisura and the lesser and greater curvature of the body. If the total score is ≥5 points, the patient is considered at higher risk of GC.27

Summary of management recommendations- -

A high-quality endoscopic examination of the gastric mucosa should be assured during a first diagnostic gastroscopy. Protocolised biopsies from the antrum (better including incisura) and the body must be sent in two separated vials and including additional guided biopsies from endoscopic areas of atrophy or IM.

- -

A high-quality histological report should be informed according the Updated Sydney recommendations (5 parameters) including the severity of atrophy and IM (mild, moderate or marked) which allows the better patient's risk stratification. Presence of incomplete IM should be reported. If the OLGA score is used, it must be provided by the pathologist.

- -

Patients at higher histological risk (OLGA/OLGIM III/IV, extensive atrophy/IM or incomplete IM) should be offered for endoscopic surveillance every 3 years (balancing risk/benefits and considering the patient's age and comorbidities).

- -

Patients with IM who do not meet high-risk criteria, should be assessed considering other factors before being excluded from endoscopic surveillance. These factors are: family history of GC, persistent HP infection, presence of autoimmune gastritis, and high-risk ethnicity or immigrants from high-incidence regions (such as Asians or Latin American population). In such cases, endoscopic surveillance should be also offered.