To estimate the management of UC associated costs from the societal perspective in Spain.

MethodsObservational, longitudinal study with retrospective data collection based on reviews of outpatient health records. Socio-demographic, clinical and sick leave information was gathered. Patients diagnosed of UC between 2002 and 2012, older than 18 years, followed-up by a minimum of 12 months post diagnosis, with at least two clinical and use of resources data recorded, were included.

Results285 UC patients [51.2% men; 44.5 (SD: 15.6) years old; 88.4% without family history of UC; 39.3% proctitis; 5.6 (2.5) years disease follow-up] participated. More than half (65.6%) were active workers, 75.9% were on sick leave for reasons different from UC [mean 0.66 (0.70) times per year] during (mean) 28.43 (34.45) days. Only 64 patients were on UC-related sick-leaves, lasting (mean) 26.17 (37.43) days. Absenteeism due to medical visits caused loss of 29.55 (21.38) working hours per year. Mean direct and indirect annual cost per UC patient were €1754.10 (95%CI: 1473.37–2034.83) and €399.32 (282.31–422.69), respectively. Absenteeism was estimated at €88.21(32.72–50.06) per patient per year, in which sick-leaves were the main component of indirect costs (88.2%). Age, UC family history, diarrhea at diagnosis, blood and blood-forming organs diseases and psychological disorders were the main predictors of indirect costs.

ConclusionsUC is a costly disease for the society and the Spanish National Healthcare System. Indirect costs imply a major burden by affecting the most productive years of patients. Further research is needed considering all components of productivity loss, including presenteeism-associated costs.

Evaluar la gestión de los gastos asociados a la CU desde la perspectiva social en España.

MétodosEstudio observacional, longitudinal con recopilación de datos retrospectiva basado en reseñas de registros sanitarios ambulatorios. Se compiló información sociodemográfica, clínica y de bajas por enfermedad. Se incluyó a aquellos pacientes diagnosticados con CU entre 2002 y 2012, mayores de 18 años, con un seguimiento después del diagnóstico como mínimo a los 12 meses y con al menos 2 de los datos clínicos y de uso de recursos registrados.

ResultadosParticiparon 285 pacientes con CU (51,2% hombres; 44,5±15,6 años); 88,4% sin antecedentes familiares de CU; 39,3% proctitis; 5,6±2,5 años de seguimiento de la enfermedad). Más de la mitad (65,6%) eran trabajadores en activo, un 75,9% estaban de baja por enfermedad por motivos ajenos a la CU (un promedio de 0,66 [0,70] veces al año) durante (media±desviación estándar) 28,43±34,45 días. Solo 64 pacientes estuvieron de baja por enfermedad relacionada con la CU, con una duración (media) de 26,17±37,43 días. El absentismo ocasionado por las visitas al médico originó una pérdida de 29,55±21,38 hs de trabajo al año. El promedio directo e indirecto del coste anual por cada paciente con CU fue de 1.754,10 € (IC95%, 1.473,37-2.034,83) y de 399,32€ (282,31-422,69), respectivamente. El absentismo se calculó en 88,21€ (32,72-50,06) por paciente al año, donde las bajas médicas son el mayor componente de los gastos indirectos (88,3%). La edad, los antecedentes familiares, la diarrea en el momento de diagnóstico, las enfermedades sanguíneas o de los órganos hematopoyéticos y los trastornos psicológicos fueron los principales factores predisponentes de los gastos indirectos.

ConclusionesLa CU es una enfermedad costosa para la sociedad y el Sistema Nacional de Salud español. Los gastos indirectos suponen una gran carga, al afectar a los años más productivos de los pacientes. Se precisa una mayor investigación que tenga en cuenta todos los componentes de la pérdida de productividad, entre otros los gastos asociados al presentismo laboral.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) caused by the continued inflammation of the colon mucosa which affects the rectum and a variable extension of the colon. UC may also have extra-intestinal manifestations that usually involve the skin, joints, the liver and eyes in nearly half of the affected individuals.1,2 Rectal bleeding is its cardinal symptom accompanied by diarrhea and rectal urgency. Fever, weight loss and abdominal pain are frequently present.3 Its diagnosis is based on differential diagnosis and on the clinical history, laboratory tests, imaging and endoscopic procedures with no specific biological marker existing for UC. Following the criteria of Montreal, UC can be classified in proctitis, left-side colitis or extended colitis according to its extension.3,4

The highest incidence and prevalence of UC have been seen in North Europe and North America and the lowest in continental Asia.5 UC etiology is unknown and has been linked to genetic, immunological and environmental factors.6 In Western countries, the incidence and prevalence of UC has increased in the past decades up to 8–14/100,000 and 120–200/100,000 persons, respectively.7,8 In Spain, incidence rates have increased over the past years, whose values are closer to those obtained in Northern Europe.7 Differences in Spanish incidence rates (from 2 to 9.6 per 100,000 inhabitants per year) are due to methodological differences between studies.7,9

UC is a chronic, incurable, lifelong disease that starts in young adulthood and continues throughout life. Regarding its social burden, most UC patients report frequent disturbing disease-related symptoms and have often visited their doctor or were absent from work due to UC problems over a year.10 Five years and twenty years subsequent to diagnosis, 10% and 30% of patients require surgery, respectively.11 An impaired Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) has been directly related to the number of physician visits, work absenteeism, and a higher amount of undergone procedures (p<0.001).12

Studies on the economic burden of the disease are scarce and its magnitude is little known in Spain. The extension of the disease critically determines the overall costs of its management while timely surgery seems to be associated with potential long term economic benefits.13 A Spanish study on the social and economic costs of IBD found that a patient with this disease costs 1730 € per year.14 While more detailed studies have been carried out on the direct costs of UC, and it has been shown that hospitalization, disease severity grade and disease extent correlate positively with the costs of illness, much less is known about the indirect costs of UC patients.15 Regarding the indirect costs of the disease, it has been documented that UC patients can be either absent from work or being at work while having symptoms as many as twice the general population and that their productivity loss can be similar to that of patients with other chronic conditions, including arthritis, cancer or diabetes.16 Given the limited available information locally, this study estimates the costs associated to the management of UC from a social perspective in Spain.

MethodsStudy designAn observational, longitudinal, retrospective study was conducted based on a review of outpatient health records from an administrative medical database including socio-demographic, clinical and sick leave data from patients of six primary care (PC) centers (Apenins-Montigalà, Morera-Pomar, Montgat-Tiana, Nova Lloreda, Martí-Julià and El Progrés) and one hospital (Hospital Municipal de Badalona), run by a health management organization (Badalona Serveis Assistencials S.A., Barcelona, Spain). Badalona Serveis Assistencial is a public organization with a private supply and is managed according to a business model, and its services portfolio is similar to that of most PC centers in Catalonia (Spain), with a decentralized management model and with integrated structural services. Badalona Serveis Assistencial takes care of 115,000 inhabitants of whom 17.1% are 64 or older and the assigned population is primarily urban.

The study population consisted of patients with diagnosis of UC (D94) in accordance with the International Classification PC-2 (ICPC-2)17 whose clinical and socio-demographic information were available in the database. To comply with inclusion criteria, patients had to (a) have a UC diagnosis which ICPC-2 code assigned between 1 January 2002 and 1 May 2012; (b) be older than 18 years of age; (c) have at least two clinical and resource use data recorded and (d) have 12 complete months follow-up since the diagnosis.

Ethical informationThe protocol of the study was approved by the Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Atención Primaria Jordi Gol Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Disease duration at study commencementTime from diagnosis at study commencement was calculated as the difference in years between the documented date of UC diagnosis and the date of the last use of health care resources or sick leave recorded.

Use of health care resources and cost estimatesHealth care resource utilization implied the number of general practitioner (GP) visits by all causes (UC related and non-related), number of referrals to the gastroenterologist, number of emergency room visits, number of hospitalizations and length of hospital stays (days); number of laboratory tests performed by all causes, and number and type of drug prescriptions reimbursed by the Spanish National Health Service (NHS). Biological treatments were not recorded in the database.

Unitary costs of health care resources were obtained from the CatSalut published tariffs.18 Direct costs were estimated multiplying the unitary cost of each individual health care resource used by the corresponding frequency of its use. To estimate the annual cost per patient, the direct cost calculated for the observation period was divided into the corresponding number of follow-up years. All costs were expressed in Euros 2012.

Productivity loss and cost estimatesOnly actively working patients were considered for estimating productivity loss associated to UC. Working days lost because of related and non-related UC sick leave, as recorded in the database, and medical visits in actively working individuals were taken into account. It was assumed that each medical visit implied the loss of half of a working day (4h) for each employed person.

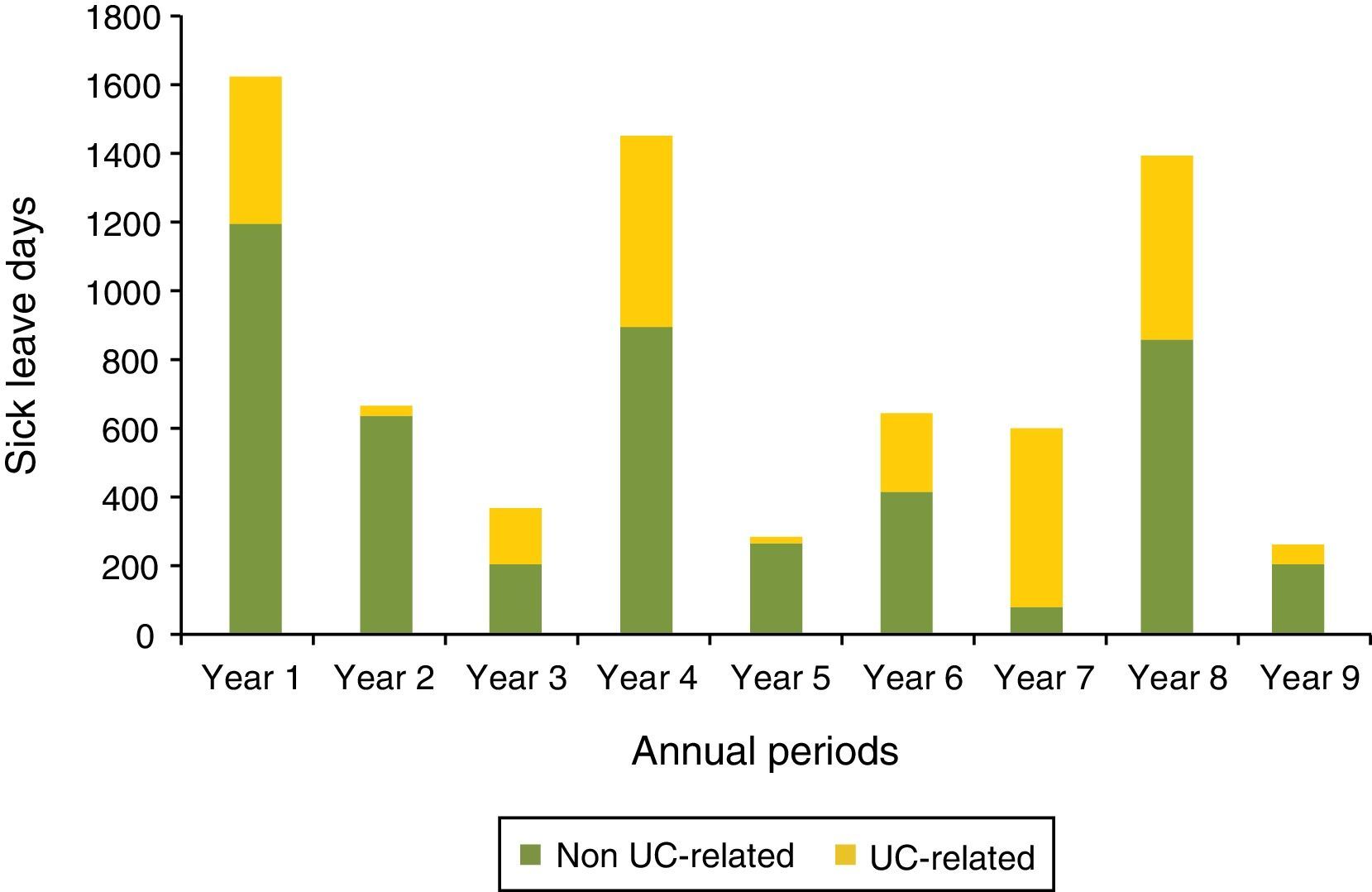

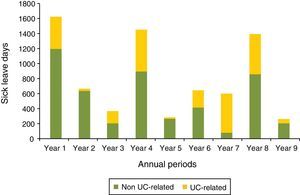

A longitudinal description of sick leave duration in the subgroup of patients with at least 9 years follow-up in the database was described. UC-related sick leaves were distinguished from the remaining causes.

Productivity loss was calculated as the sum of the yearly number of working days lost during sick leave and the time invested in medical visits (absenteeism) multiplied by the daily average inter-professional salary rate for Spain.19 To estimate the annual cost per patient, the indirect cost calculated for the observation period was divided into the corresponding number of follow-up years.

Statistical methodsA descriptive analysis was carried out in order to describe the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of study subjects. Absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables, and mean and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables were calculated.

Cost results were expressed as mean, SD and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Additional information about the distribution of the sample according to indirect costs was obtained dividing the patients into two groups using an arbitrary Z score of 2 defined as follows: patients with a Z score >2, whose indirect cost exceeded the mean cost by 2 SDs, and patients with a Z score ≤2, whose mean indirect cost was below the mean by 2 SDs. This analysis allowed distributing the sample of patients into two UC patients’ profiles by their cost estimates: patients with indirect costs closer to the mean, and patients with higher than the mean indirect costs.

A linear regression model was carried out to determine which variables have an effect on the indirect costs (dependent variable). Independent variables were demographic and clinical characteristics of patients. A stepwise procedure was implemented in order to select the best predictive set of variables according to Akaike information criteria.20,21 Statistical software R22 was used to perform the analysis and a significant level of 5% was considered.

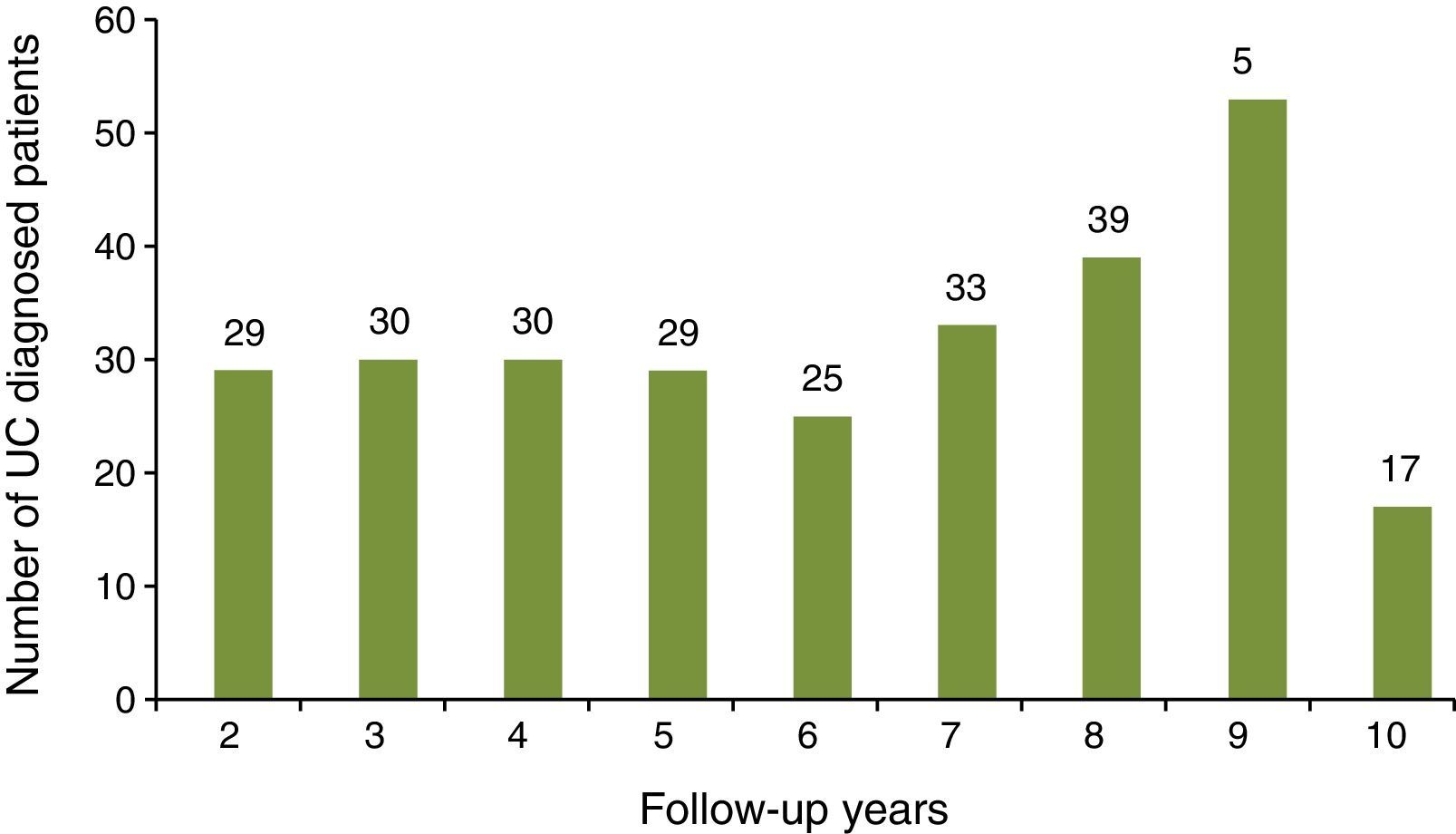

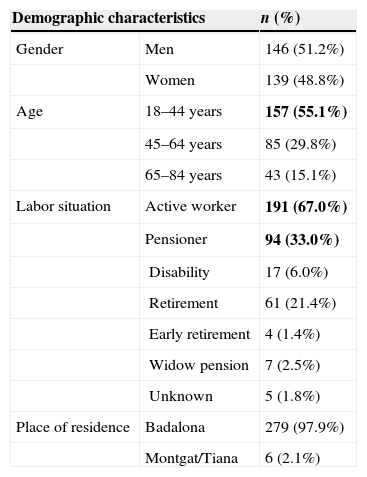

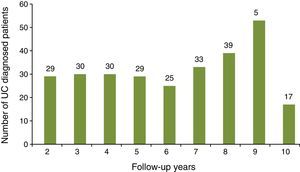

ResultsDemographic and clinical characteristics of the sampleA total of 385 UC patients were initially identified during the study observation period of whom 100 did not accomplish the inclusion criteria (14 patients were younger than 18 years old; 5 patients were diagnosed later than 1 May 2012; 81 patients did not have 12 complete months since UC diagnosis code had been assigned). The study sample corresponds to a total of 285 subjects. Disease follow-up duration varied between 2 and 10 years, with a mean of 5.6 years (SD: 2.5) (Fig. 1).

Half of patients were men (51.2%). Mean age was 44.5 (SD: 15.6) ranging from 18 to 84 years. More than half of the subjects were active workers (65.6%) at the time of study (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of study subjects.

| Demographic characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 146 (51.2%) |

| Women | 139 (48.8%) | |

| Age | 18–44 years | 157 (55.1%) |

| 45–64 years | 85 (29.8%) | |

| 65–84 years | 43 (15.1%) | |

| Labor situation | Active worker | 191 (67.0%) |

| Pensioner | 94 (33.0%) | |

| Disability | 17 (6.0%) | |

| Retirement | 61 (21.4%) | |

| Early retirement | 4 (1.4%) | |

| Widow pension | 7 (2.5%) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1.8%) | |

| Place of residence | Badalona | 279 (97.9%) |

| Montgat/Tiana | 6 (2.1%) | |

Bold text indicates most relevant results.

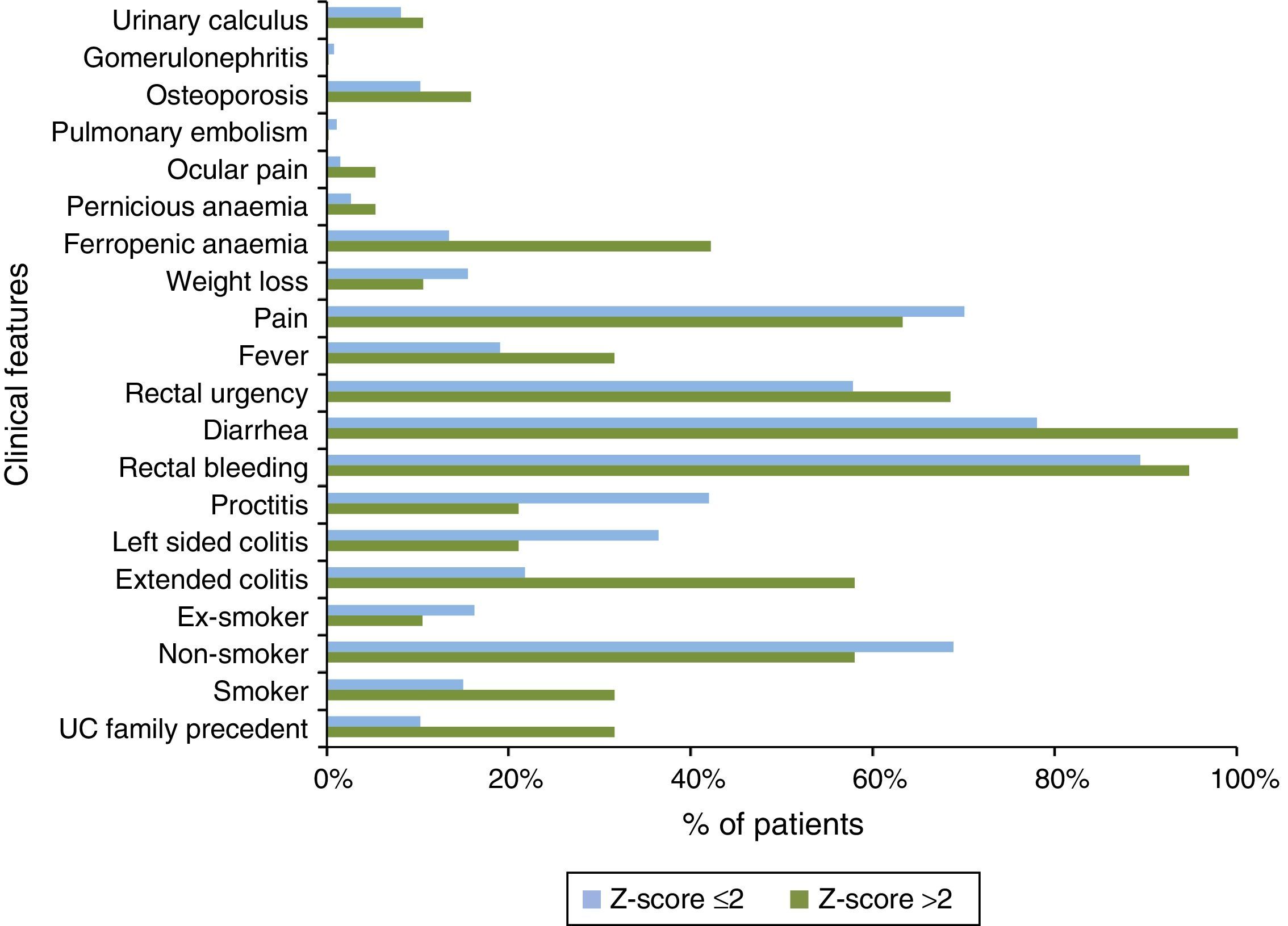

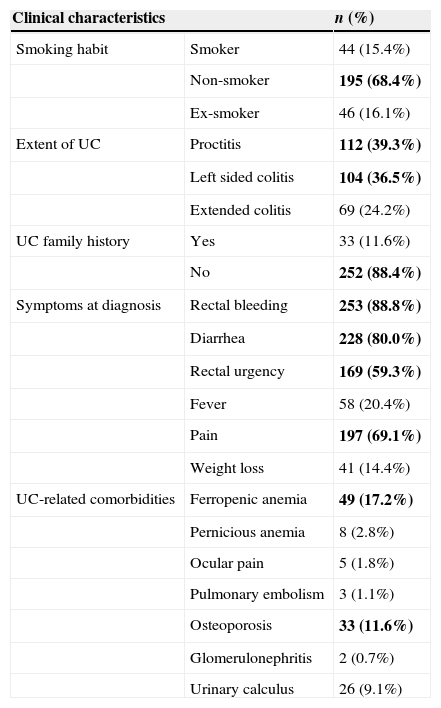

With regard to the clinical characteristics of the sample (Table 2), patients were mostly non-smokers (68.4%) with no family history of UC (88.4%). The extent of UC was fairly similar amongst the studied individuals with extended colitis representing the least frequent expression of the disease (proctitis, 39.3%; left side, 36.5%; extended colitis, 24.2%). The most usual symptoms at diagnosis were rectal bleeding (88.8%), diarrhea (80.0%), pain (69.1%) and rectal urgency (59.3%).

Clinical characteristics of study subjects.

| Clinical characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking habit | Smoker | 44 (15.4%) |

| Non-smoker | 195 (68.4%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 46 (16.1%) | |

| Extent of UC | Proctitis | 112 (39.3%) |

| Left sided colitis | 104 (36.5%) | |

| Extended colitis | 69 (24.2%) | |

| UC family history | Yes | 33 (11.6%) |

| No | 252 (88.4%) | |

| Symptoms at diagnosis | Rectal bleeding | 253 (88.8%) |

| Diarrhea | 228 (80.0%) | |

| Rectal urgency | 169 (59.3%) | |

| Fever | 58 (20.4%) | |

| Pain | 197 (69.1%) | |

| Weight loss | 41 (14.4%) | |

| UC-related comorbidities | Ferropenic anemia | 49 (17.2%) |

| Pernicious anemia | 8 (2.8%) | |

| Ocular pain | 5 (1.8%) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Osteoporosis | 33 (11.6%) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Urinary calculus | 26 (9.1%) | |

Bold text indicates most relevant results.

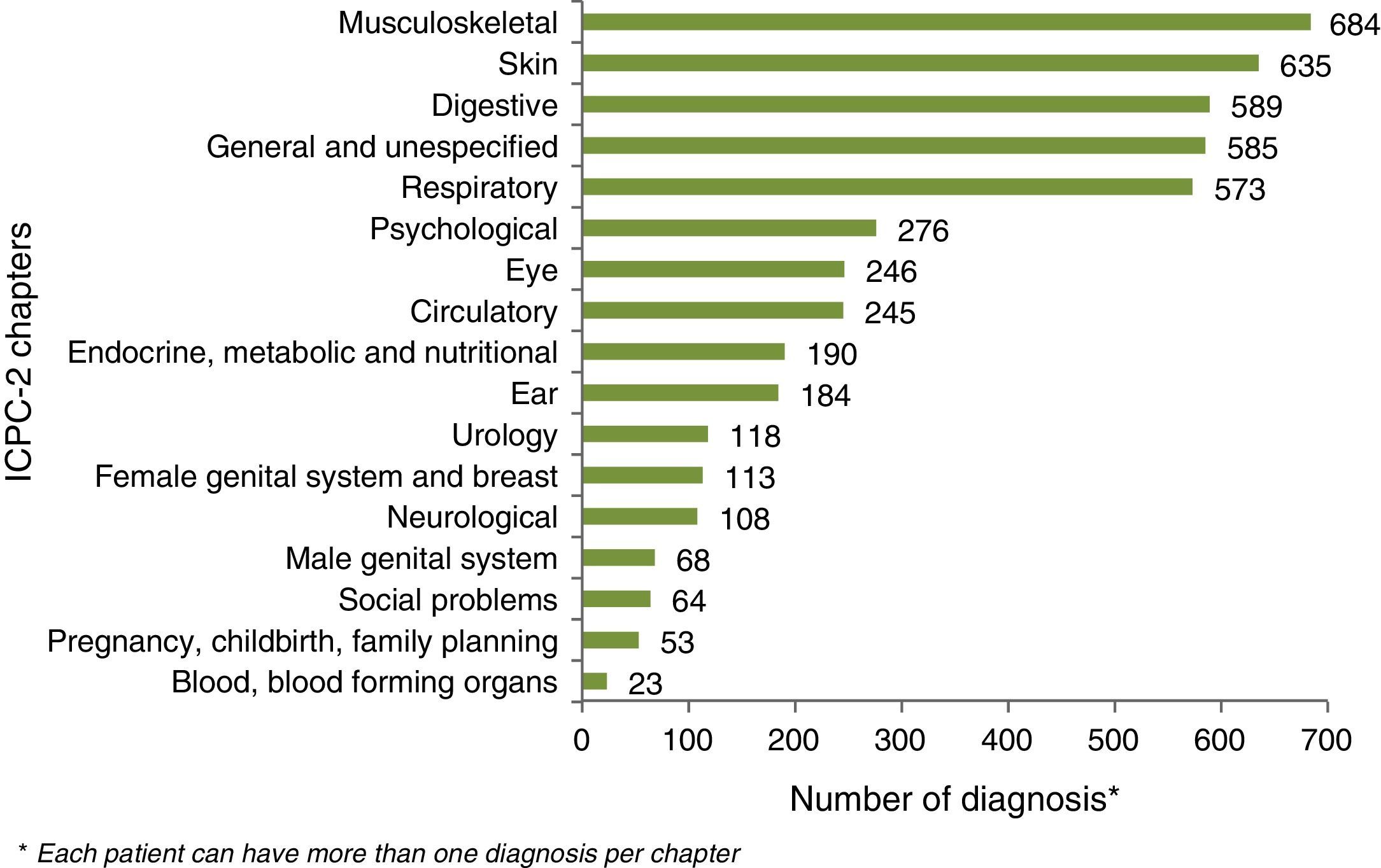

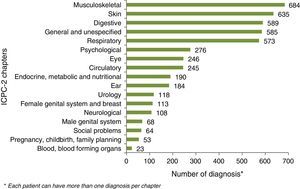

Ferropenic anemia was the most common UC-related co morbidity (17.2%) followed by osteoporosis (11.6%) and urinary calculus (9.1%). UC non-related comorbidities were mostly related to digestive and the musculoskeletal system and to skin pathologies (Fig. 2).

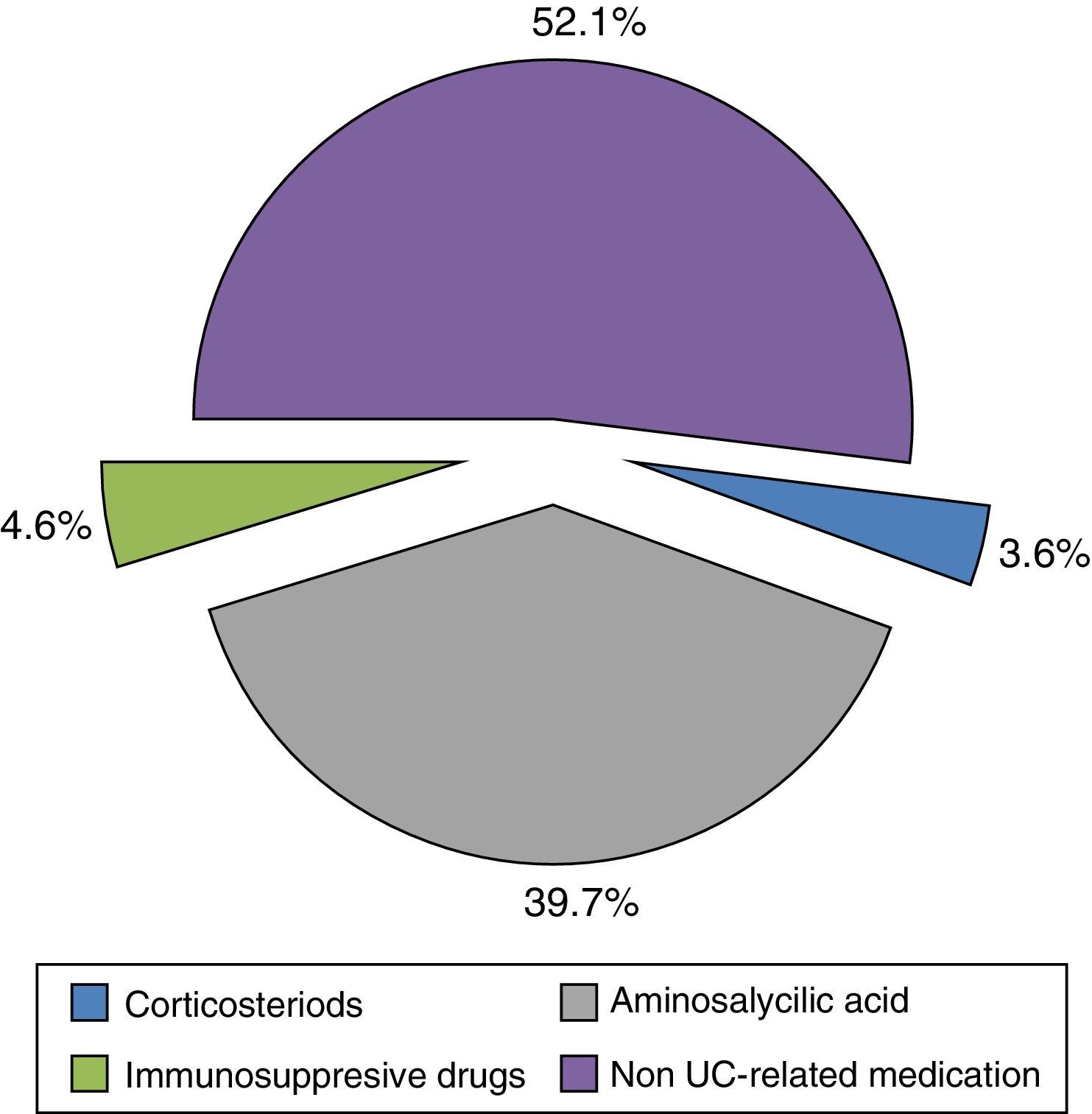

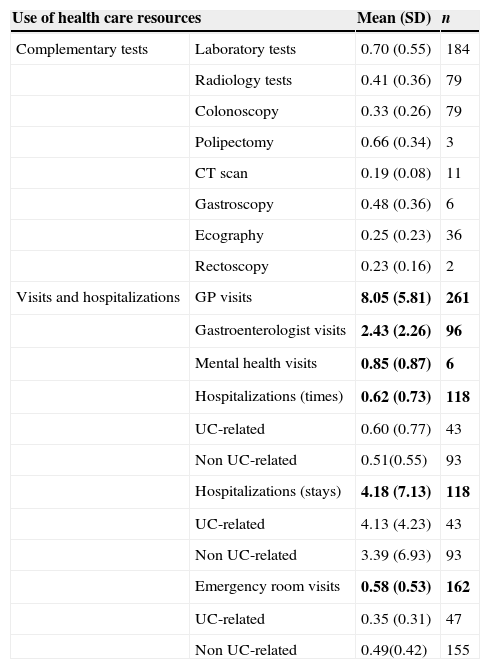

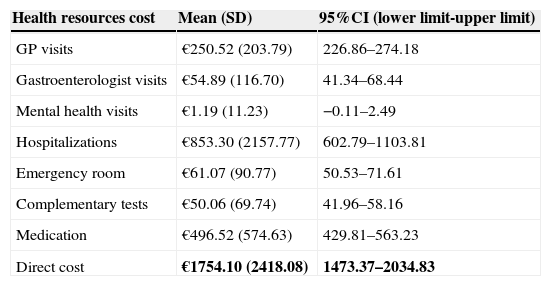

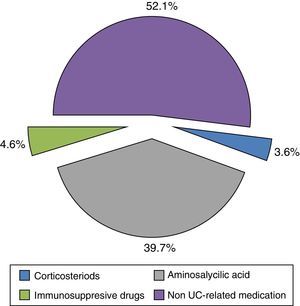

Resource utilization and direct costIn regard to visits and hospitalizations for any cause, patients visited the GP 8.05 (SD: 5.81) times per year and were hospitalized less than once a year [mean: 0.62 (SD: 0.73)]. Patients who were admitted into hospital due to UC-related causes had a relatively short stay duration [mean: 4.13 (SD: 4.23) days per year] (Table 3). Less than one laboratory test per patient [mean 0.70 (SD: 0.55)] was performed per year. Other diagnostic tests, such as radiological images [mean 0.41 (SD: 0.36)] and colonoscopies [mean 0.33 (SD: 0.26)], were performed less frequently (Table 3). Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as corticosteroids and amino salicylic acid, were used by 74.0% of patients while immunosuppressive drugs were prescribed up to 21.4% (Table 4). Biological treatments were not recorded.

Annual use of health care resources.

| Use of health care resources | Mean (SD) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complementary tests | Laboratory tests | 0.70 (0.55) | 184 |

| Radiology tests | 0.41 (0.36) | 79 | |

| Colonoscopy | 0.33 (0.26) | 79 | |

| Polipectomy | 0.66 (0.34) | 3 | |

| CT scan | 0.19 (0.08) | 11 | |

| Gastroscopy | 0.48 (0.36) | 6 | |

| Ecography | 0.25 (0.23) | 36 | |

| Rectoscopy | 0.23 (0.16) | 2 | |

| Visits and hospitalizations | GP visits | 8.05 (5.81) | 261 |

| Gastroenterologist visits | 2.43 (2.26) | 96 | |

| Mental health visits | 0.85 (0.87) | 6 | |

| Hospitalizations (times) | 0.62 (0.73) | 118 | |

| UC-related | 0.60 (0.77) | 43 | |

| Non UC-related | 0.51(0.55) | 93 | |

| Hospitalizations (stays) | 4.18 (7.13) | 118 | |

| UC-related | 4.13 (4.23) | 43 | |

| Non UC-related | 3.39 (6.93) | 93 | |

| Emergency room visits | 0.58 (0.53) | 162 | |

| UC-related | 0.35 (0.31) | 47 | |

| Non UC-related | 0.49(0.42) | 155 | |

Bold text indicates most relevant results.

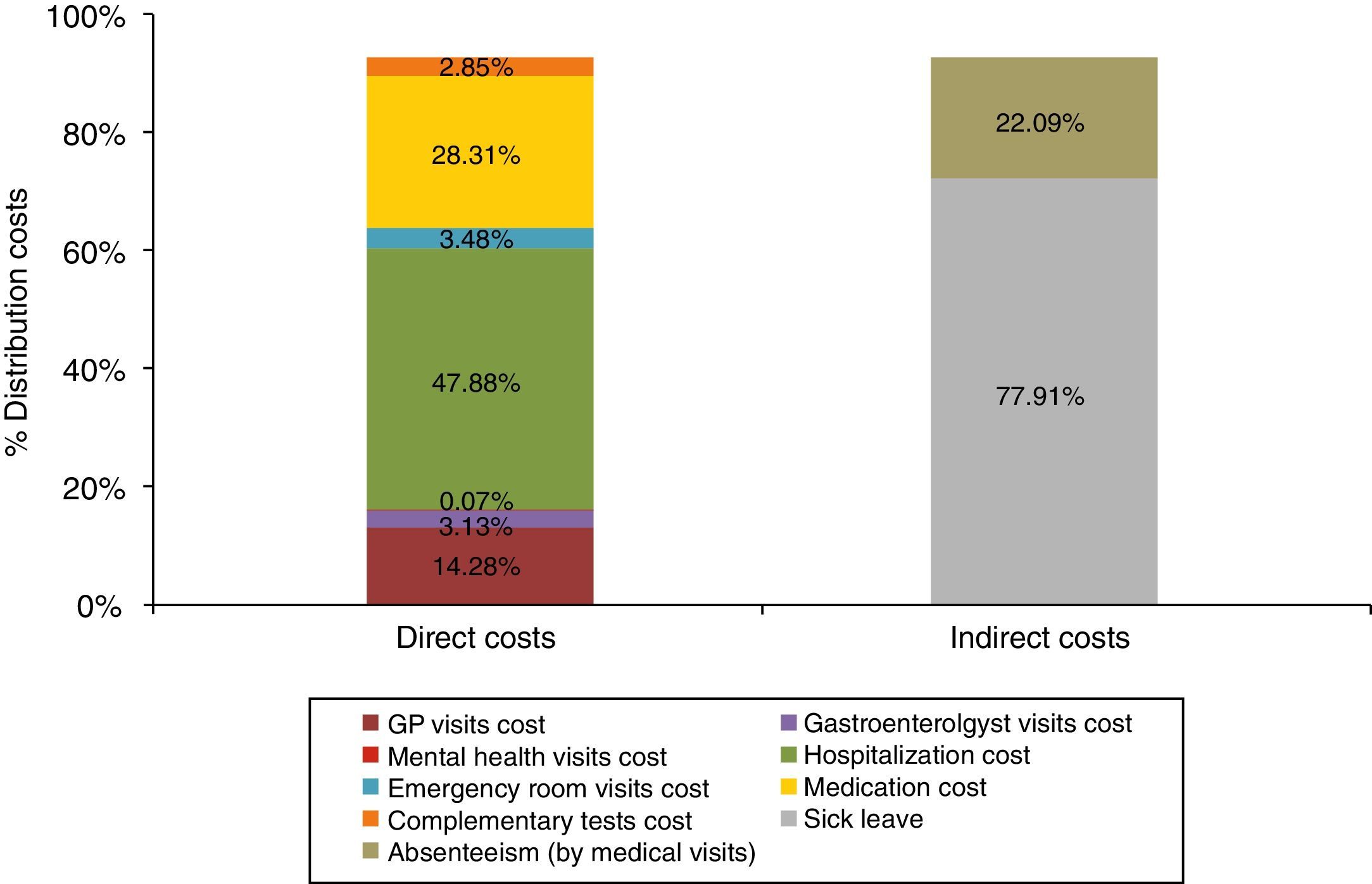

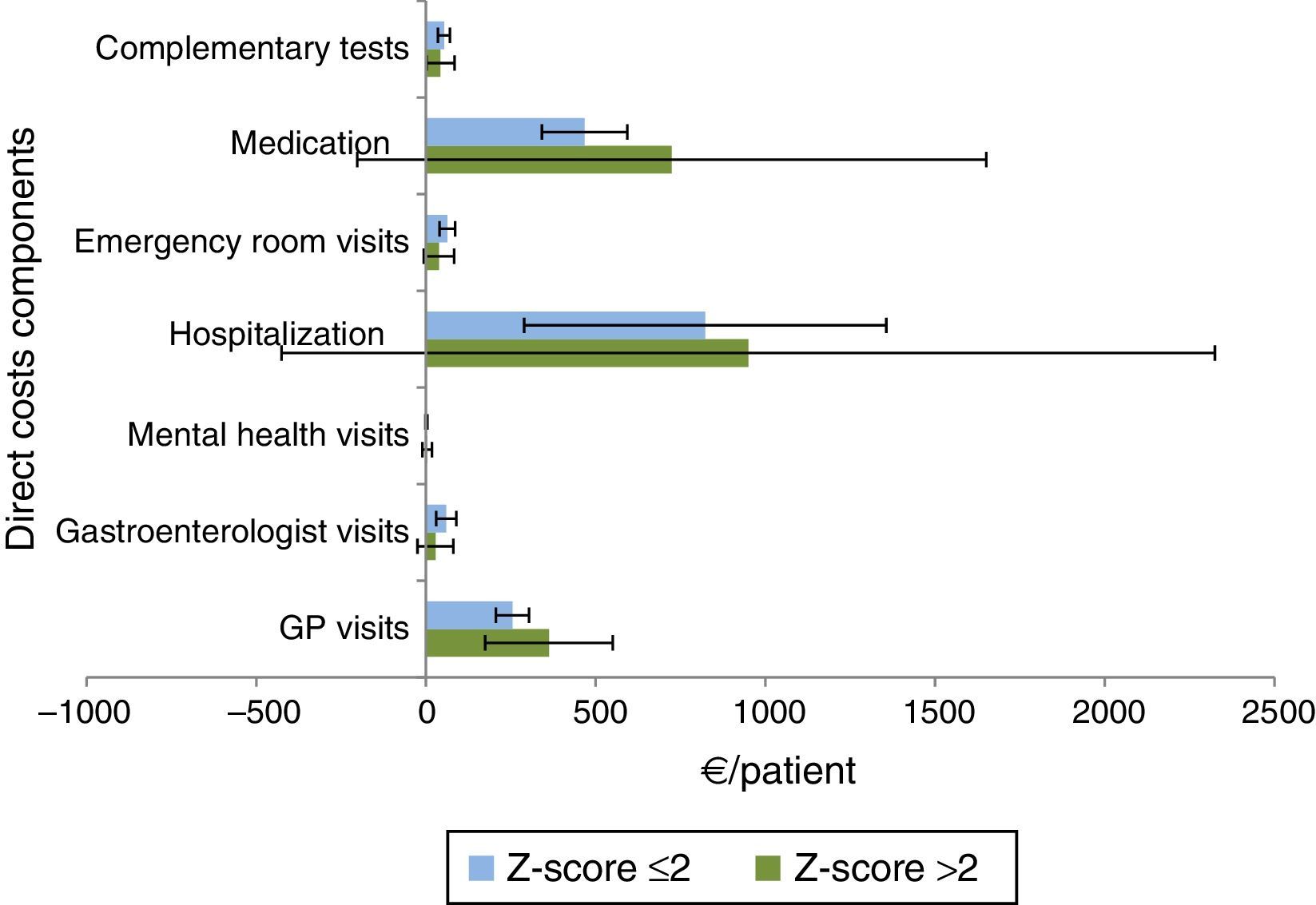

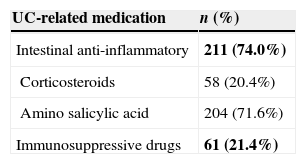

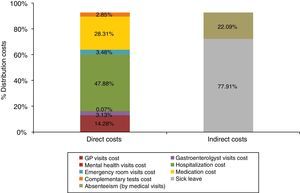

The mean direct annual cost of an UC ambulatory patient was €1754.10 (95%CI: 1473.37–2034.83) (Table 5). The main components of direct costs were hospitalizations (47.88%) and the prescribed pharmacological treatments (28.31%) for any cause (Fig. 3). 48% of medication cost was due to UC-related drugs (Fig. 4).

Annual direct costs estimates.

| Health resources cost | Mean (SD) | 95%CI (lower limit-upper limit) |

|---|---|---|

| GP visits | €250.52 (203.79) | 226.86–274.18 |

| Gastroenterologist visits | €54.89 (116.70) | 41.34–68.44 |

| Mental health visits | €1.19 (11.23) | −0.11–2.49 |

| Hospitalizations | €853.30 (2157.77) | 602.79–1103.81 |

| Emergency room | €61.07 (90.77) | 50.53–71.61 |

| Complementary tests | €50.06 (69.74) | 41.96–58.16 |

| Medication | €496.52 (574.63) | 429.81–563.23 |

| Direct cost | €1754.10 (2418.08) | 1473.37–2034.83 |

Bold text indicates most relevant results.

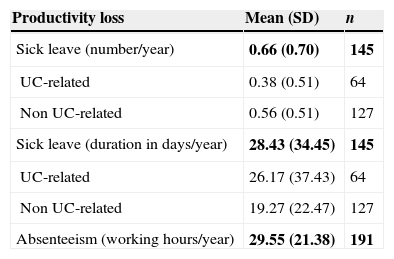

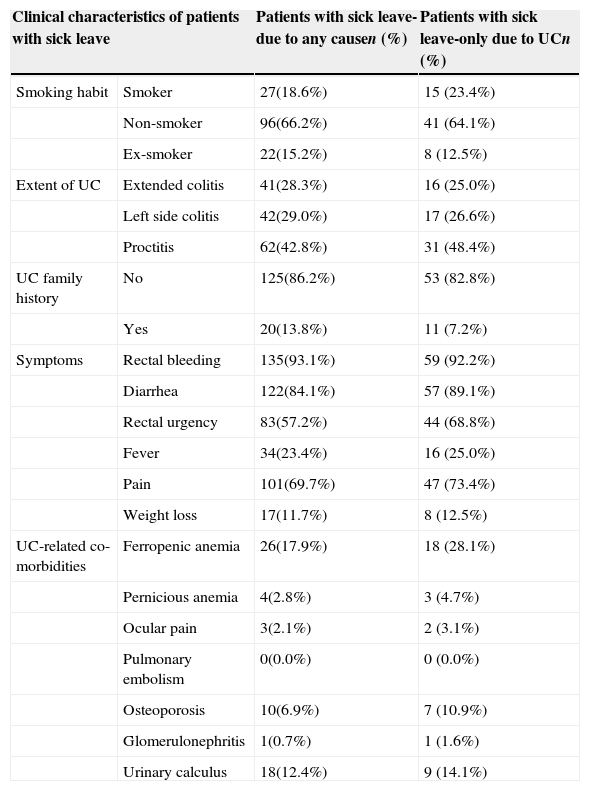

More than half of patients in the sample [65.6% (n=191)] were active workers; 145 of them had been on sick leave [mean 0.66 times (SD: 0.70) per year] for 28.43 days (SD: 34.45). Only 64 patients had a UC-related sick leave for 26.17 days (SD: 37.43). Absenteeism due to medical visits in these patients caused losing a mean of 29.55 working hours (SD: 21.38) per year (Table 6). Table 7 describes the clinical characteristics of patients with UC-related sick leave. 53.1% of patients were women. The mean age was 34.72 (SD: 9.46) years, mostly non-smokers (64.1%), with proctitis as subtype of the disease (48.4%) and without UC family history (82.8%). Most common symptoms were rectal bleeding (92.2%), diarrhea (89.1%), pain (73.4%) and rectal urgency (68.8%). In relation to UC-related co-morbidities, ferropenic anemia (28.1%) and urinary calculus (14.1%) were the most frequent diagnosis.

Annual productivity loss caused by sick leave.

| Productivity loss | Mean (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|

| Sick leave (number/year) | 0.66 (0.70) | 145 |

| UC-related | 0.38 (0.51) | 64 |

| Non UC-related | 0.56 (0.51) | 127 |

| Sick leave (duration in days/year) | 28.43 (34.45) | 145 |

| UC-related | 26.17 (37.43) | 64 |

| Non UC-related | 19.27 (22.47) | 127 |

| Absenteeism (working hours/year) | 29.55 (21.38) | 191 |

Bold text indicates most relevant results.

Clinical characteristics of patients on sick leave.

| Clinical characteristics of patients with sick leave | Patients with sick leave-due to any causen (%) | Patients with sick leave-only due to UCn (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking habit | Smoker | 27(18.6%) | 15 (23.4%) |

| Non-smoker | 96(66.2%) | 41 (64.1%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 22(15.2%) | 8 (12.5%) | |

| Extent of UC | Extended colitis | 41(28.3%) | 16 (25.0%) |

| Left side colitis | 42(29.0%) | 17 (26.6%) | |

| Proctitis | 62(42.8%) | 31 (48.4%) | |

| UC family history | No | 125(86.2%) | 53 (82.8%) |

| Yes | 20(13.8%) | 11 (7.2%) | |

| Symptoms | Rectal bleeding | 135(93.1%) | 59 (92.2%) |

| Diarrhea | 122(84.1%) | 57 (89.1%) | |

| Rectal urgency | 83(57.2%) | 44 (68.8%) | |

| Fever | 34(23.4%) | 16 (25.0%) | |

| Pain | 101(69.7%) | 47 (73.4%) | |

| Weight loss | 17(11.7%) | 8 (12.5%) | |

| UC-related co-morbidities | Ferropenic anemia | 26(17.9%) | 18 (28.1%) |

| Pernicious anemia | 4(2.8%) | 3 (4.7%) | |

| Ocular pain | 3(2.1%) | 2 (3.1%) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0(0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Osteoporosis | 10(6.9%) | 7 (10.9%) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1(0.7%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Urinary calculus | 18(12.4%) | 9 (14.1%) | |

For patients with at least a 9 years follow-up recorded in the database since the UC diagnosis (n=70), the duration of sick leave in days for each year was described (Fig. 5). The number of days due to sick leave per year for any cause was higher during the first, fourth and the eighth year while sick leaves caused by UC were more frequent in the first, fourth, seventh and eighth years. The non-parametric test equivalent to repeated measures ANOVA, Friedman test, showed statistically significant differences in duration of sick leave for any cause between years (p=0.028). In contrast, differences in duration of sick leave due to UC were not significant (p=0.929).

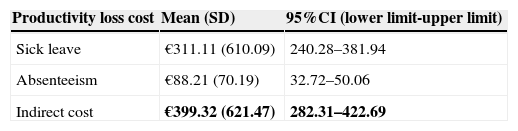

The mean annual indirect cost per patient was €399.32 (95%CI: 282.31–422.69). The main component of indirect cost was sick leave (88.25%) (Fig. 3). Absenteeism was estimated at €88.21 per patient per year (95%CI: 32.72–50.06) (Table 8).

The mean total annual cost of UC patients reached to €2153.42 (95%CI: 1809.97–2403.25), direct and indirect costs represented 81.5% and 18.5%, respectively.

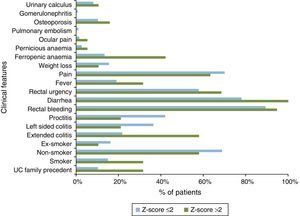

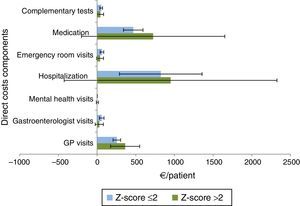

Indirect cost subgroup analysisFurther information about the distribution of the sample of working patients according to its indirect cost was obtained by grouping the participants using a Z-score of 2, defined as the indirect cost exceeding the mean cost by 2 SDs. That division allowed two profiles of patients to be defined: patients with indirect costs locked to an average expenditure (Z-score ≤2) and patients with higher indirect cost estimates (Z-score >2). Patients with a Z-score ≤2 (253 patients) and patients with a Z-score >2 (19 patients) were described.

UC patients defined by their higher indirect costs (Z-score >2) were mostly women (63.2% vs. 48.49%) and younger compared with Z-score ≤2 group patients [mean 44.7 (SD: 15.6) vs. mean 36.9 (SD: 9.5)]. UC disease duration (in years) was similar in both groups [mean 5.8 (SD: 2.5) vs. mean 5.7 (SD: 2.4)].

Also, differences in clinical characteristics between Z-score groups were observed (Fig. 6). Patients with Z-score >2 showed family history of UC (31.6% vs. 10.3%); smoking habits (31.6% vs. 15.0%); extended colitis subtype (57.9% vs. 21.7%) and UC symptoms as diarrhea (100.0% vs. 77.9%), rectal urgency (68.4% vs. 57.7%), and fever (31.6% vs. 19.0%) at diagnosis when compared with Z-score ≤2 patients. Consistent with previous characteristics, ferropenic anemia was the UC co-morbidity most frequently diagnosed in Z-score >2 patients group (42.1% vs. 13.3%).

Z-score >2 patients used more health resources compared with patients with Z-score ≤2 (Fig. 7), with higher costs due to hospitalizations [mean €949.50 (95%CI: 261.90–1637.11) vs. mean €822.93 (95%CI: 556.07–1089.79)] and medications [mean €724.31 (95%CI: 261.12–1187.50) vs. mean €467.33 (95%CI: 404.42–530.24)].

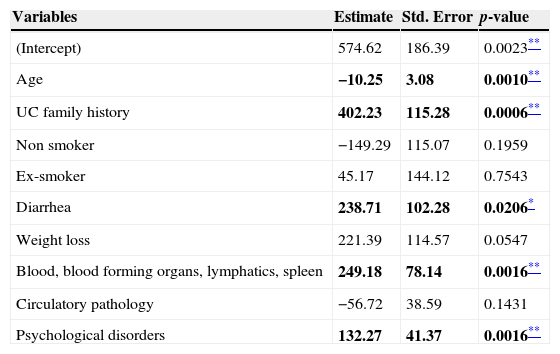

Factors influencing indirect costsA linear regression model was conducted in order to assess the effect of socio-demographic (age and gender) and clinical variables (UC duration, smoking habit, extent of UC, UC family history, symptoms and ICPC-2 co-morbidities) on the indirect costs in UC patients (Table 9). A stepwise approach was followed.

Linear regression model: influence of demographic and clinical variables on indirect cost in UC patients.

| Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 574.62 | 186.39 | 0.0023** |

| Age | −10.25 | 3.08 | 0.0010** |

| UC family history | 402.23 | 115.28 | 0.0006** |

| Non smoker | −149.29 | 115.07 | 0.1959 |

| Ex-smoker | 45.17 | 144.12 | 0.7543 |

| Diarrhea | 238.71 | 102.28 | 0.0206* |

| Weight loss | 221.39 | 114.57 | 0.0547 |

| Blood, blood forming organs, lymphatics, spleen | 249.18 | 78.14 | 0.0016** |

| Circulatory pathology | −56.72 | 38.59 | 0.1431 |

| Psychological disorders | 132.27 | 41.37 | 0.0016** |

Bold text indicates most relevant results.

Variables affecting costs (p<0.05) were age, UC family history, the presence of diarrhea and the number of ICPC-2 co-morbidities related to blood-forming organ diseases and due to psychological disorders. The highest coefficient corresponded to UC family history which implied an increase on indirect costs of €402.23 per patient compared to patients with no UC family history. The second coefficient with the highest effect on indirect costs was the presence of diarrhea. Patients with diarrhea were significantly more expensive (€238.71) than patients without it. For each additional diagnosis of blood-forming organs and of psychological problems, indirect costs increased by €249.18 and €132.27, respectively, per patient. Age had a negative effect on indirect costs: for each year of older age, indirect costs decreased by €10.25 per patient.

DiscussionThis study incorporates direct and indirect cost estimates in UC patients managed in a regional health care area in Spain. With regard to direct costs, findings are similar to those obtained in previous European publications. A study carried out in the United Kingdom estimated the direct costs of IBD, including UC patients, during a 6 months follow-up. Results showed that hospitalizations represented approximately 50% of direct costs followed by drugs prescriptions that corresponded to 25% of direct costs.15 Another study carried out in Israel and 8 European countries, including Spain, evaluated the expenditure on health care in Crohn's disease and UC patients during 10 years follow-up. The mean direct costs estimated for Spanish UC patients was €1524 (SD €4101) which were comparable to the results of the present study.23 None of these studies included biological treatment costs.

More recent studies have included the use of biological therapies in the treatment of UC.24,25 The study from EpiCom group showed that 3% of UC patients from Western Europe received biological treatment as rescue therapy.24 The other study carried out in Holland estimated the healthcare costs of IBD. Results showed that the use of biological therapies was the main costs driver, accounting for 31% of the total cost in UC patients.25

In the studied sample, visits to emergency room and hospital admissions were infrequent with less than one admission per year per patient, whereas hospital stays were short, probably indicating that no surgery for UC took place during admissions. These results were consistent with those obtained from an Italian 10-year cohort study based on electronic database registries. Although UC patients had at least 1 or more hospitalization during the follow-up period, only 9.5% of admissions implied a surgical procedure while over 90% of them had a diagnostic and/or medical therapeutic purpose.26

To project the direct costs of UC, it has to be considered that approximately one-third of patients with long-standing disease will require surgery during their lifetime, mainly due to medically refractory illness or to the development of colorectal dysplasia or colorectal cancer.27,28 Patients requiring hospitalization and surgery are among the most costly UC cases.29 The armamentarium of medical therapies currently available to both induce and maintain remission represents the second cost driver of the disease. In this study, medical treatment was the second component of direct costs despite biological treatment costs not being collected as no information was gathered directly from hospital databases.

Mean age of the studied population corresponded to individuals of working age, but with a slightly shorter duration of the disease than that observed in other European studies considering indirect costs.15,29,30 Indirect costs represented less than 20% of the total costs of the disease and implied productivity losses of about 26 days due to UC related sick leave and about 30h of working time lost because of medical visits, per patient and year. These figures show the important economic burden of UC. Only a few European recent studies calculate indirect costs of UC patients representing 5%15 to 68%29 of total costs, depending on the report. Bassi et al. carried out a 6-month study in the United Kingdom obtaining costs data from a postal questionnaire. The number of disease-related visits to a primary care doctor, out of pocket expenses, employment status and number of lost working days due to UC were collected. The results showed that 32% of employed patients with UC had loss of productivity with median annual indirect costs per patient amounting to €533 (£239).15 In Germany, the study carried out by Stark et al.29 analyzed the use of healthcare facilities, medications, sick leave, out-of-pocket expenditures and long-term disability in UC patients using cost diaries. A total cost of €1015 (95%CI 832–1258) per patient during 4 weeks was calculated, 54% of which were indirect costs. Methodological disparities as well as the costs attached to the loss of productivity and to medicines paid out-of-pocket may easily explain the costs differences observed between these studies.23

An additional description of participants was obtained using a Z-score which has shown to be useful to determine the distribution of a sample beyond a mean in cost studies.31 By selecting an arbitrary Z score, it is possible to identify groups of patients with higher costs who may potentially be different from other patients. It could then be argued that addressing the particular needs of these patients may contribute to reducing the mean annual costs of the disease. In the studied sample, patients with higher Z-score had showed more proportions of UC family history, smoking habits, extended UC subtype, ferropenic anemia, and diarrhea and fever at diagnosis. These patients represented higher health expenditures due to hospitalizations and medications.

When a regression model was conducted, factors with significant influence on indirect costs were age, smoking habit, family history of UC, psychological disorders and certain UC unrelated comorbidities. Amongst these features, family history of UC imposed the most significant effect on raising indirect costs. Comparison of these results with other studies cannot be conducted because regression model analysis considering only indirect cost has not been reported in the reviewed studies.15,29 Further insights are needed on the long term effects of these factors on the different components of the indirect costs of UC.

Findings reported for this study have to be interpreted in the context of its limitations inherent to its design, the nature of data coming from an administrative medical database and the costs used. Although a previous study carried out in Canada32 that compared self-reported and administrative data in IBD patients showed high concordance between both sources of information for collecting data on medical resource use, more precise data gathering methods on productivity loss need to be put in place. For a more accurate description of the social consequences of UC from an economic point of view, reduced productivity of paid work (presenteeism) and reduced opportunities for unpaid activities (loss of leisure) need to be assessed. They are more difficult to measure and require directly asking the patient. Their knowledge would allow for a more precise estimation of the true burden of UC in society, particularly in the actively working population. Results apply only to a local area in Spain and extrapolation to the entire population should not be attempted. No data about the general population (without UC) were collected to compare the use of resources and productivity losses vs. UC patients. This information would give results on the real prospect of the costs of the UC. Along the same lines, to put the results in the context of the Catalan population, it would be of interest to compare the population seen in Badalona Serveis Assistencials organization with the rest of Catalan population with ulcerative colitis. Nonetheless, the findings depict the magnitude of UC burden even if patients with mild disease in the primary care setting are to be considered. Given the way data are collected in the database, only hospital admissions and emergency room visits, together with sick leave due to UC could be distinguished from all disease causes. Although this seems to be a fairly common limitation in this type of design,33 average estimates for any disease cause had to be calculated.

In summary, UC is a costly disease for society and the healthcare system in Spain. Indirect costs imply a major burden by affecting individuals in the most productive years of their lives. Further research is needed taking into account all components of productivity loss including preseentism, particularly in the mild and moderate forms of the disease, when medical treatment has a key role to play in keeping the illness under control.

Conflict of interestsThe project was funded by AbbVie. AbbVie reviewed the final draft publication content for medical and scientific accuracy, and for intellectual property considerations, when applicable. The authors declare no conflicts of interests. The authors were responsible for all final content decisions and for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authors’ contributionX.A. and A.S. were expert advisors who participated in the interpretation of results, critically reviewed and drafted the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Outcomes’10 for its collaboration in the development of the project and for the assistance in the critical revision of the manuscript and Dr. Xavier Calvet for the critical revision of the manuscript.