A 67-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension and religious orientation of Jehovah's Witness, and refusing to receive red cell concentrate (RCC) transfusions, was admitted for acute lower gastrointestinal haemorrhage (LGH). By performing an initial colonoscopy, the LGH was associated with a sigmoid diverticular origin, without locating any specific bleeding point for treatment. Because of exteriorization persistence, an abdominal angiography computed tomography (angioCT), an arteriography, and a second colonoscopy were performed, with no possibility of therapeutic application. Haemoglobin (Hb) levels progressively decreased to 4.2g/dL. After compassionate administration of a barium enema, no new episodes of bleeding were reported, allowing discharge of the patient 12 days’ post-enema, with an Hb level of 6.4g/dL. At 88 months of follow-up, no new LGH episodes had been detected.

A 91-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, congestive heart failure, and atrial fibrillation on antiplatelet treatment was admitted for acute painless LGH, with initial haemodynamic instability. An angioCT was performed, visualizing multiple diverticula in the whole colonic tract, with an active bleeding point in the cecum. The patient did well and arterial blood pressure values returned to normal. Colonoscopy showed a cecal diverticulum with a visible vessel, treated with adrenaline and a haemostatic clip. Despite the endoscopic treatment, blood exteriorization persisted, with daily RCC transfusion requirements. During the following three weeks two more colonoscopies were carried out, along with a second angioCT with an arteriography, without revealing a specific bleeding spot to be treated. Finally, a barium enema was administered, leading to the cessation of the LGH. At 17 days’ post-enema, the patient was discharged, with an Hb of 8.5g/dL, after having received a total transfusion support of 17 RCC during the 5 weeks of admission. No new episodes of LGH were detected at 5 months of follow-up, when the patient was admitted for cardiac decompensation and acute pulmonary oedema with an end-of-live denouement.

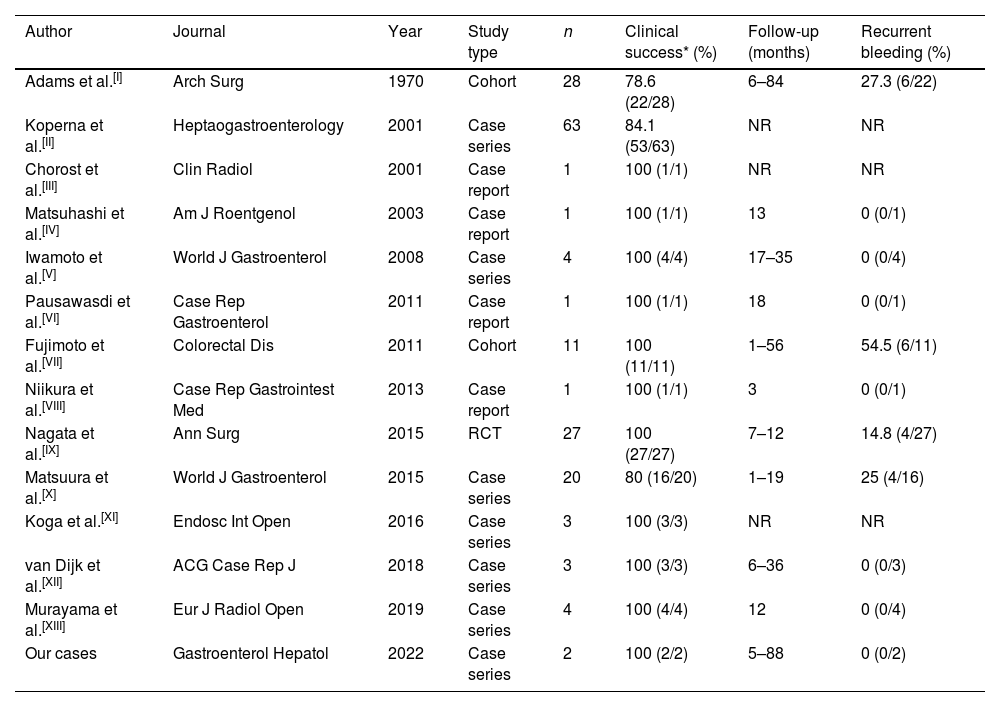

LGH of diverticular origin is the main cause of bleeding below the angle of Treitz requiring hospital admission in patients over 50 years of age. The usual clinical course in this type of bleeding is self-limiting (80–90% of cases). However, there are patients who require aggressive management of the pathology, with the need for RCC transfusion support, as well as interventions such as colonoscopy, arteriography, or even surgery.1 The patient's comorbidities and/or antecedents may lead to situations of contraindication of the usual management algorithms in this type of pathology, as in the two cases presented in this scientific letter. The use of barium enema as a therapeutic option in case of LGH of diverticular origin was first reported in 1970 by Adams et al.2 Since then, a string of publications have appeared, most of them in the form of case-reports or short series of cases like our experience (Table 1).3 Only one randomized clinical trial has been published, highlighting the usefulness of high-dose barium impaction therapy in the long-term prevention of recurrent bleeding (42.5% vs. 14.8%; log-rank test, P=0.04).2

Previous scientific literature on therapeutic barium enema for colonic diverticular haemorrhage (adapted, expanded, and updated from3).

| Author | Journal | Year | Study type | n | Clinical success* (%) | Follow-up (months) | Recurrent bleeding (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al.[I] | Arch Surg | 1970 | Cohort | 28 | 78.6 (22/28) | 6–84 | 27.3 (6/22) |

| Koperna et al.[II] | Heptaogastroenterology | 2001 | Case series | 63 | 84.1 (53/63) | NR | NR |

| Chorost et al.[III] | Clin Radiol | 2001 | Case report | 1 | 100 (1/1) | NR | NR |

| Matsuhashi et al.[IV] | Am J Roentgenol | 2003 | Case report | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 13 | 0 (0/1) |

| Iwamoto et al.[V] | World J Gastroenterol | 2008 | Case series | 4 | 100 (4/4) | 17–35 | 0 (0/4) |

| Pausawasdi et al.[VI] | Case Rep Gastroenterol | 2011 | Case report | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 18 | 0 (0/1) |

| Fujimoto et al.[VII] | Colorectal Dis | 2011 | Cohort | 11 | 100 (11/11) | 1–56 | 54.5 (6/11) |

| Niikura et al.[VIII] | Case Rep Gastrointest Med | 2013 | Case report | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 3 | 0 (0/1) |

| Nagata et al.[IX] | Ann Surg | 2015 | RCT | 27 | 100 (27/27) | 7–12 | 14.8 (4/27) |

| Matsuura et al.[X] | World J Gastroenterol | 2015 | Case series | 20 | 80 (16/20) | 1–19 | 25 (4/16) |

| Koga et al.[XI] | Endosc Int Open | 2016 | Case series | 3 | 100 (3/3) | NR | NR |

| van Dijk et al.[XII] | ACG Case Rep J | 2018 | Case series | 3 | 100 (3/3) | 6–36 | 0 (0/3) |

| Murayama et al.[XIII] | Eur J Radiol Open | 2019 | Case series | 4 | 100 (4/4) | 12 | 0 (0/4) |

| Our cases | Gastroenterol Hepatol | 2022 | Case series | 2 | 100 (2/2) | 5–88 | 0 (0/2) |

NR: not reported; RCT: randomized clinical trial.

[I] Adams JT. Therapeutic barium enema for massive diverticular bleeding. Arch Surg 1970;101:457–60. [II] Koperna T, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bleeding colonic diverticula. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:702–5. [III] Chorost MI, et al. The therapeutic barium enema revisited. Clin Radiol 2001;56:856–8. [IV] Matsuhashi N, et al. Barium impaction therapy for refractory colonic diverticular bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180:490–2. [V] Iwamoto J, et al. Therapeutic barium enema for bleeding colonic diverticula: four case series and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:6413–7. [VI] Pausawasdi N, et al. Therapeutic high-density barium enema in a case of presumed diverticular haemorrhage. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2011;5:88–94. [VII] Fujimoto A, et al. Effectiveness of high-dose barium enema filling for colonic diverticular bleeding. Colorectal Dis 2011;13:896–8. [VIII] Niikura R, et al. High-dose barium impaction therapy is useful for the initial hemostasis and for preventing the recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding unresponsive to endoscopic clipping. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2013;2013:365954. [IX] Nagata N, et al. High-dose barium impaction therapy for the recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2015;261:269–75. [X] Matsuura M, et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic barium enema for diverticular haemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:5555–9. [XI] Koga M, et al. Barium impaction therapy with balloon occlusion for deep colonic diverticular bleeding: a three-case series. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E560-3. [XII] van Dijk B, et al. Barium enema for treatment for diverticular bleeding. ACG Case Rep J 2018;5:e71. [XIII] Murayama Y, et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic standard concentration barium enema for colonic diverticular bleeding: Preliminary results. Eur J Radiol Open 2019;6:139–43.

When performing a colonoscopy in case of colonic diverticular bleeding, it is difficult to locate the bleeding vessel and it is usually not possible to apply targeted therapy. Recently, non-directed endoscopic haemostatic techniques using haemostatic powder devices have appeared, with favourable results described (initial clinical success greater than 95%, with one-month rebleeding rate of 5.5–12.9%).4,5 Although the use of the barium enema might hypothetically be compared to these devices for non-directed attempts at haemostasis, the published literature is limited and a direct causal relationship between its use and LGH cessation cannot be clearly established, because in most cases the bleeding ceases spontaneously. Barium enema might be an option to consider in selected cases, like the two presented here, in which the usual management options for diverticular LGH are not successful, or when it is not possible to apply them. More studies with larger numbers of patients would be needed to clarify its use as a compassionate therapy for diverticular LGH.

Authors’ contributionsJosep Mª Botargues, Mireia Peñalva, Antonio Soriano, Jordi Guardiola: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the article, and final approval.

Francesc Bas-Cutrina, Albert Martín-Cardona, Francisco Rodríguez-Moranta: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the article, editing of the table, critical revision of the article, and final approval.

Ethical approvalThe study researchers have carried out their tasks in compliance with the ethical principles of clinical research established in the Declaration of Helsinki, and with the norms of Good Clinical Practices (International Conference on Harmonization).

The data underlying this short report cannot be shared publicly in order to protect the privacy of the subjects for ethical/privacy reasons. The data, without personal identification of participant subjects, will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

FundingNo specific funding has been received. Data have been generated as part of our routine work at our hospital.

Conflict of interestAlbert Martín-Cardona has received financial support for travelling and educational activities from Abbvie, Biogen, Ferring, Jannsen, MSD, Takeda, Dr Falk Pharma and Tillotts.

Jordi Guardiola has served as a speaker and as consultant for or has received research or education funding from MSD, Abbvie, Kern, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Roche and General Electric.

Francisco Rodríguez-Moranta has served as a speaker for Abbvie, Takeda, Pfizer, Jansen, and MSD, and has served as an advisor for Abbvie, Jansen, MSD, and Pfizer.

The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.