Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a severe clinical entity associated with elevated short-term mortality. We aimed to characterize patients with decompensated cirrhosis according to presence of ACLF, their association with active alcohol intake, and long-term survival in Latin America.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study of decompensated cirrhotic in three Chilean university centers (2017-2019). ACLF was diagnosed according EASL-CLIF criteria. We assessed survival using competing-risk and time-to-event analyses. We evaluated the time to death using accelerated failure time (AFT) models.

ResultsWe included 320 patients, median age of 65.3±11.7 years old, and 48.4% were women. 92 (28.7%) patients met ACLF criteria (ACLF-1: 29.3%, ACLF-2: 27.1%, and ACLF-3: 43.4%). The most common precipitants were infections (39.1%), and the leading organ failure was kidney (59.8%). Active alcohol consumption was frequent (27.7%), even in patients with a prior diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (16.2%). Ninety-two (28.7%) patients had ACLF (ACLF-1: 8.4%, ACLF-2: 7.8%, and ACLF-3: 12.5%). ACLF patients had a higher MELD-Na score at admission (27 [22-31] versus 16 [12-21], p<0.0001), a higher frequency of alcohol-associated liver disease (36.7% versus 24.9%, p=0.039), and a more frequent active alcohol intake (37.2% versus 23.8%, p=0.019). In a multivariate model, ACLF was associated with higher mortality (subdistribution hazard ratio 1.735, 95%CI: 1.153-2.609; p<0.008). In the AFT models, the presence of ACLF during hospitalization correlated with a shorter time to death: ACLF-1 shortens the time to death by 4.7 times (time ratio [TR] 0.214, 95%CI: 0.075-0.615; p<0.004), ACLF-2 by 4.4 times (TR 0.224, 95%CI: 0.070-0.713; p<0.011), and ACLF-3 by 37 times (TR 0.027, 95%CI: 0.006-0.129; p<0.001).

ConclusionsPatients with decompensated cirrhosis and ACLF exhibited a high frequency ofactive alcohol consumption. Patients with ACLF showed higher mortality and shorter time todeath than those without ACLF.

La insuficiencia hepática aguda sobre crónica (ACLF, por sus siglas en inglés) es una entidad clínica grave asociada con una elevada mortalidad a corto plazo. Nuestro objetivo fue caracterizar a los pacientes con cirrosis descompensada según la presencia de ACLF, su asociación con la ingesta activa de alcohol y la supervivencia a largo plazo en América Latina.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte retrospectivo de cirróticos descompensados en tres centros universitarios chilenos (2017-2019). La ACLF se diagnosticó según los criterios EASL-CLIF. Evaluamos la supervivencia mediante análisis de riesgo competitivo y de tiempo hasta el evento. Evaluamos el tiempo hasta la muerte usando modelos de tiempo de falla acelerada (AFT).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 320 pacientes, mediana de edad de 65,3±11,7 años, y el 48,4% eran mujeres. Un total de 92 (28,7%) pacientes cumplieron criterios de ACLF (ACLF-1 29,3%, ACLF-2 27,1%, y ACLF-3 43,4%). Los precipitantes más frecuentes fueron las infecciones (39,1%) y la principal insuficiencia orgánica fue la renal (59,8%). El consumo activo de alcohol fue frecuente (27,7%), incluso en pacientes con diagnóstico previo de enfermedad de hígado graso no alcohólico (EHGNA) (16,2%); 92 (28,7%) pacientes tenían ACLF (ACLF-1: 8,4%, ACLF-2: 7,8% y ACLF-3: 12,5%). Los pacientes con ACLF tenían una puntuación MELD-Na más alta al ingreso (27 [22-31] frente a 16 [12-21], p<0,0001), una mayor frecuencia de enfermedad hepática asociada al alcohol (36,7% frente a 24,9%, p=0,039), y una ingesta activa de alcohol más frecuente (37,2% frente a 23,8%, p=0,019). En un modelo multivariado, ACLF se asoció con una mayor mortalidad (cociente de riesgos instantáneos de subdistribución 1,735, IC del 95%: 1,153-2,609; p<0,008). En los modelos AFT, la presencia de ACLF durante la hospitalización se correlacionó con un menor tiempo hasta la muerte: ACLF-1 acortó el tiempo hasta la muerte en 4,7 veces (relación de tiempo [TR] 0,214, IC 95%: 0,075-0,615; p<0,004), en ACLF-2 4,4 veces (TR 0,224, IC 95%: 0,070-0,713; p<0,011), y en ACLF-3 en 37 veces (TR 0,027, IC 95%: 0,006-0,129; p<0,001).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con cirrosis descompensada y ACLF presentaban una alta frecuencia de consumo activo de alcohol. Los pacientes con ACLF mostraron una mayor mortalidad y un tiempo más corto hasta la muerte que aquellos sin ACLF.

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) was first described in 1995 as a particular clinical entity of acute severe deterioration in patients with chronic liver disease.1 Currently, ACLF is considered a syndrome associated with intense systemic inflammation and single- or multiple-organ failure, which usually develops in close temporal relationships with proinflammatory precipitating events.2 This syndrome occurs in up to 30% of hospitalized cirrhotic patients, and most of them require intensive medical support, reaching a 90-day mortality of 60%.3–5 More than 13 definitions of ACLF have been proposed in the last decades.6 The most widely used are the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF),3 the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NASCELD),7 and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) definitions.8 ACLF has a huge impact on the healthcare system, and the costs per hospitalization for ACLF are five times higher than for patients with cirrhosis but without ACLF.9 Also, the costs associated with ACLF increased 5-fold from $320 million to $1.7 billion annually between 2001 and 2011 in the United States (US).9

ACLF is usually preceded by some initial harmful event, such as hazardous alcohol intake.3,10 Patients with ACLF are generally younger and have a higher prevalence of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), infections, and increased inflammatory parameters than decompensated cirrhotics that did not meet ACLF criteria.5 Some studies suggest that the prevalence and severity of ACLF have a linear association with alcohol consumption, which determines its severity and prognosis.2,11 A recent study in the US showed a rise in admissions due to ALD in younger patients, with a notably higher prevalence of ACLF in this population.12 Therefore, alcohol intake could modulate the development and prognosis of decompensated cirrhotics. Metabolic risk factors such as hypertension (HTN) and type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) are also associated with poor outcomes in patients with ACLF.13 For example, a study including 96 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and ACLF evidenced that T2DM increased the risk of death at 90 days (odds ratio [OR] 3.60).14

The lack of unified criteria has resulted in heterogeneous epidemiological data on ACLF, making it very difficult to predict the prevalence and outcomes of ACLF worldwide.15,16 Only a few studies have evaluated the incidence and prognosis of ACLF criteria in Latin America. Studies conducted in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico have evidenced an incidence of 24-37% in hospitalized decompensated patients with cirrhosis.17–21 However, some authors have reported essential differences in clinical characteristics and a higher mortality rate in the Latin American population compared to North American and European cohorts.19 These differences might be related to the significant heterogeneity in etiologies of cirrhosis and patterns of alcohol intake,22 genetic background, health care access disparities,23 and significant differences in the existence and implementation of public health policies on alcohol, non-alcohol fatty liver disease (NAFLD), viral hepatitis, and cirrhosis among Latin American countries.24,25 Therefore, to better estimate the incidence and clinical implications of ACLF in Hispanic patients, we aimed to characterize patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ACLF in a Chilean multicenter cohort study, identifying precipitant factors, relationship with alcohol intake, organ failure prevalence during admission, and long-term prognosis based on the EASL-CLIF consortium ACLF criteria.

MethodsStudy design and participantsWe conducted a retrospective registry-based study of patients admitted for decompensated cirrhosis in the regular ward unit, intermediate unit, and intensive care unit (ICU), between January 1st, 2017, and December 31st, 2019, in three centers: Hospital Clínico Red de Salud UC-CHRISTUS (Santiago, Chile), Hospital del Salvador (Santiago, Chile), and Hospital Clínico de la Universidad de Chile (Santiago, Chile). We included all patients with cirrhosis, regardless of the etiology and severity, who were admitted due to decompensation of cirrhosis, defined as one or more of the following complications: ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (based on West Haven scale criteria), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (confirmed by an upper endoscopy), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and suspected bacterial or fungal infection. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on the clinical history and imaging by the attending physician. A liver biopsy was not mandatory for inclusion and was considered only in clinical uncertainty by the attending physician. The data on the etiologies of cirrhosis were obtained from the clinical records, lacking details of therapy indications for all of them (for example, we did not have records regarding the use of direct antivirals in HCV or NUC treatment in HBV). We excluded patients aged under 18-year-old, pregnant women, acute or subacute liver failure without underlying cirrhosis, patients with cirrhosis who develop decompensation in the postoperative period after partial hepatectomy, advanced or metastatic local stage neoplasia, severe extrahepatic diseases previously known (chronic kidney failure on hemodialysis, severe heart disease, or severe chronic lung disease), use of immunosuppressants drugs, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection without treatment.

We defined organ failure and ACLF using the EASL-CLIF consortium criteria.3 Liver failure was defined with serum bilirubin≥12mg/dL; renal failure: serum creatinine≥2mg/dL or renal replacement therapy; coagulation failure: an International Normalized Ratio (INR)≥2.5; brain failure: HE grades 3 or 4; and circulatory failure: the need for vasopressor/s; and respiratory failure as PaO2/FiO2<200, SpO2/FiO2<214, or need of mechanical ventilation.3 We established the diagnosis of a confirmed infection based on clinical, microbiological, and radiological features using the NACSELD consortium criteria.26 The infections were diagnosed by the attending clinicians, who were not part of the study group. The alcohol consumption was defined as mild (<10g per day in women and men), moderate (between 10 and 20g per day in women and 10–30g per day in men), and excessive (>20g per day in women and >30g in men per day).27,28

Data collectionWe used a de-identified electronic spreadsheet database to collect data from patients with the aforementioned criteria. Two independent reviewers registered all information after data extraction in each center. A third reviewer was consulted in case of differences between the two reviewers. We obtained demographic, clinical, and analytical data recorded on days 0, 4, 8, and discharge. Mortality and liver transplantation (LT) were assessed using the publicly available Chilean national registry. The history of alcohol consumption was obtained from the clinical records and psychiatric interviews during admission. Only the main researchers of the study managed the electronic database. We requested an informed consent waiver at each participating center, and de-identified data were analyzed.

Statistical analysisContinuous data were described using mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile ranges [IQR] for those variables without normal distribution. Normal distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Nominal data were described using percentages. To compare numerical variables with normal distribution, Student's t-test or ANOVA was used. For numerical variables that do not have a normal distribution, non-parametric tests were used. In the case of multiple proportions, the p-value was estimated using binomial regression with a log link function.

Initially, we conducted a transplant-free survival study employing Kaplan–Meier analysis, which measured survival time from admission to the time of death. Subsequently, we analyzed the risk of mortality using competing risk survival models, allowing us to estimate a subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR). The cause-specific hazards for survival were estimated through a competing-risk model. The primary event of interest was mortality in presenting with ACLF criteria, and the competing event corresponds to LT. The SHR and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to report these results. Also, we used accelerated failure time models (AFT) for time-to-event analysis, where the event was defined as death. We used the AFT model instead of the Cox proportional hazards model. Under AFT models, we measure the direct effect of the explanatory variables on the survival time instead of the hazard, as we do in the proportional hazards models.29 The AFT model better fits the event rate in ACLF patients since the differences between the degrees of ACLF occur in the short term. This model is more appropriate when the group differences are seen over a shorter timeframe, while in the longer term, the probability of remaining event free is similar in the two groups.30 We interpret the effect of the AFT model as the change in timescale by a factor of exp(xjβ). This is a function of whether this factor is greater or less than 1, so survival time is interpreted as accelerating or decelerating. AFT does not imply a positive acceleration of time with an increase in a covariate but a deceleration or, that is, an increase in the expected waiting time to failure. We adjusted models by age, gender, history of T2DM, HTN, and coronary heart disease (CHD) as these variables, as mentioned previously, have shown to be associated with higher mortality in patients with ACLF.13,14 Statistical analysis was performed with STATA software version 17.0 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

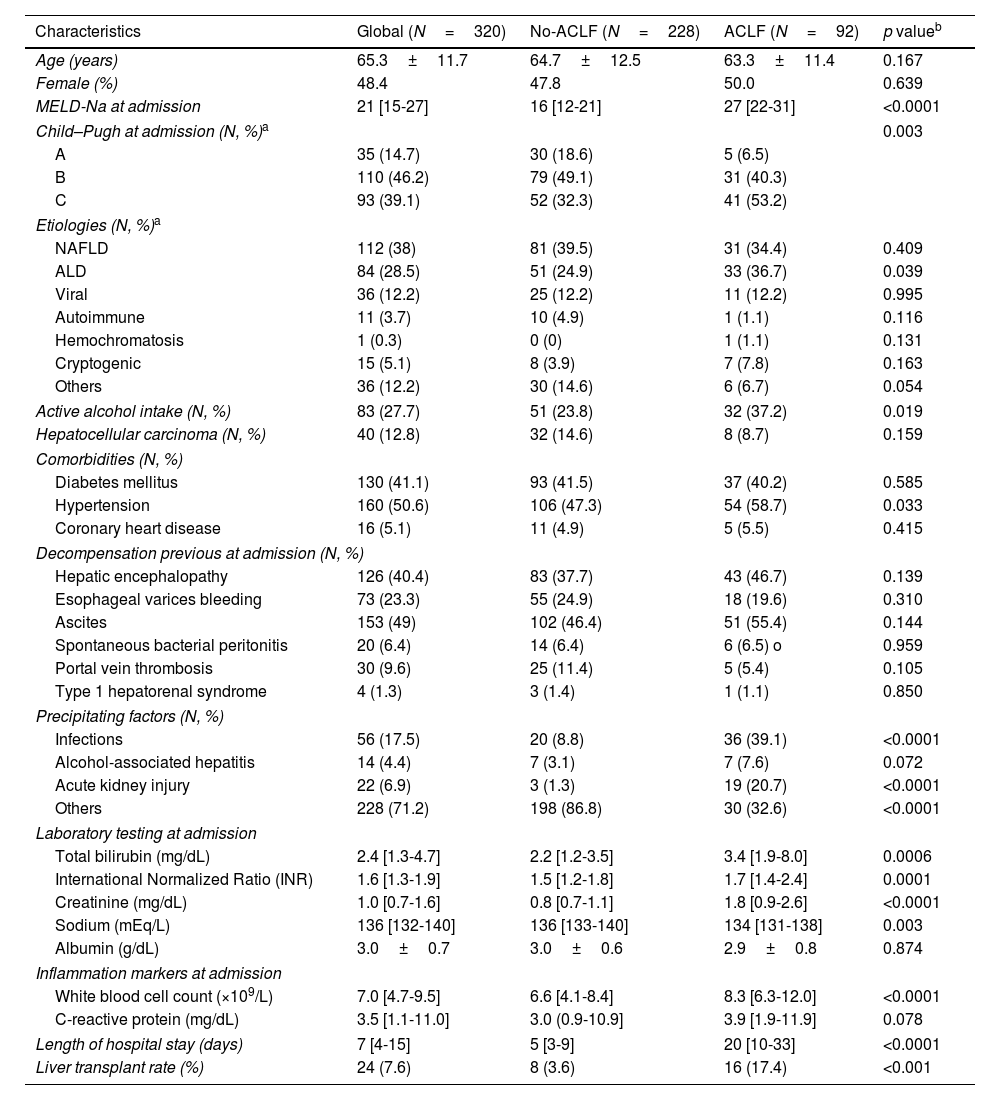

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the cohort at admissionWe included 320 patients from three Chilean university centers. The mean age was 65.3±11.7 years old, and 48.4% were women (Table 1). The main causes of cirrhosis were NAFLD (38%), ALD (28.5%), and chronic viral hepatitis (12.2%). The median Model of End-Stage Liver Disease sodium (MELD-Na) at admission was 21 [15–27], while 14.7% were Child–Pugh A, 46.2% were Child–Pugh B, and 39.1% were Child–Pugh C. The median follow-up was 520 [85–795] days, and 18 patients were readmitted within 30 days after discharge, with a median time to readmission of 14 [2–29] days. Of note, 56.1% of patients had esophageal varices bleeding, 49.0% ascites, 40.4% history of HE, 12.8% hepatocellular carcinoma, 9.6% portal vein thrombosis, and 6.4% had an episode of SBP before admission.

Main characteristics of the patients included in the study at admission.

| Characteristics | Global (N=320) | No-ACLF (N=228) | ACLF (N=92) | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.3±11.7 | 64.7±12.5 | 63.3±11.4 | 0.167 |

| Female (%) | 48.4 | 47.8 | 50.0 | 0.639 |

| MELD-Na at admission | 21 [15-27] | 16 [12-21] | 27 [22-31] | <0.0001 |

| Child–Pugh at admission (N, %)a | 0.003 | |||

| A | 35 (14.7) | 30 (18.6) | 5 (6.5) | |

| B | 110 (46.2) | 79 (49.1) | 31 (40.3) | |

| C | 93 (39.1) | 52 (32.3) | 41 (53.2) | |

| Etiologies (N, %)a | ||||

| NAFLD | 112 (38) | 81 (39.5) | 31 (34.4) | 0.409 |

| ALD | 84 (28.5) | 51 (24.9) | 33 (36.7) | 0.039 |

| Viral | 36 (12.2) | 25 (12.2) | 11 (12.2) | 0.995 |

| Autoimmune | 11 (3.7) | 10 (4.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0.116 |

| Hemochromatosis | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.131 |

| Cryptogenic | 15 (5.1) | 8 (3.9) | 7 (7.8) | 0.163 |

| Others | 36 (12.2) | 30 (14.6) | 6 (6.7) | 0.054 |

| Active alcohol intake (N, %) | 83 (27.7) | 51 (23.8) | 32 (37.2) | 0.019 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (N, %) | 40 (12.8) | 32 (14.6) | 8 (8.7) | 0.159 |

| Comorbidities (N, %) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 130 (41.1) | 93 (41.5) | 37 (40.2) | 0.585 |

| Hypertension | 160 (50.6) | 106 (47.3) | 54 (58.7) | 0.033 |

| Coronary heart disease | 16 (5.1) | 11 (4.9) | 5 (5.5) | 0.415 |

| Decompensation previous at admission (N, %) | ||||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 126 (40.4) | 83 (37.7) | 43 (46.7) | 0.139 |

| Esophageal varices bleeding | 73 (23.3) | 55 (24.9) | 18 (19.6) | 0.310 |

| Ascites | 153 (49) | 102 (46.4) | 51 (55.4) | 0.144 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 20 (6.4) | 14 (6.4) | 6 (6.5) o | 0.959 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 30 (9.6) | 25 (11.4) | 5 (5.4) | 0.105 |

| Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0.850 |

| Precipitating factors (N, %) | ||||

| Infections | 56 (17.5) | 20 (8.8) | 36 (39.1) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol-associated hepatitis | 14 (4.4) | 7 (3.1) | 7 (7.6) | 0.072 |

| Acute kidney injury | 22 (6.9) | 3 (1.3) | 19 (20.7) | <0.0001 |

| Others | 228 (71.2) | 198 (86.8) | 30 (32.6) | <0.0001 |

| Laboratory testing at admission | ||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.4 [1.3-4.7] | 2.2 [1.2-3.5] | 3.4 [1.9-8.0] | 0.0006 |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) | 1.6 [1.3-1.9] | 1.5 [1.2-1.8] | 1.7 [1.4-2.4] | 0.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 [0.7-1.6] | 0.8 [0.7-1.1] | 1.8 [0.9-2.6] | <0.0001 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136 [132-140] | 136 [133-140] | 134 [131-138] | 0.003 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.0±0.7 | 3.0±0.6 | 2.9±0.8 | 0.874 |

| Inflammation markers at admission | ||||

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 7.0 [4.7-9.5] | 6.6 [4.1-8.4] | 8.3 [6.3-12.0] | <0.0001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 3.5 [1.1-11.0] | 3.0 (0.9-10.9] | 3.9 [1.9-11.9] | 0.078 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 7 [4-15] | 5 [3-9] | 20 [10-33] | <0.0001 |

| Liver transplant rate (%) | 24 (7.6) | 8 (3.6) | 16 (17.4) | <0.001 |

A total of 92 (28.7%) patients met ACLF criteria (ACLF-1: 29.3%, ACLF-2: 27.1%, and ACLF-3: 43.4%). Around 75% of patients with ACLF fulfilled the criteria of ACLF at admission, while the in-hospital onset of ACLF was infrequent. Table 1 summarizes the main differences at admission according to the presence of ACLF. There were no significant differences between patients with ACLF and those without in terms of age (63.3±11.4 versus 64.7±12.5 years, p=0.167), gender (50% versus 47.8% women, p=0.639), and type of decompensation before admission (Table 1 and Fig. 1). ALD was more frequent in patients with ACLF (36.7% versus 24.9%, p=0.039), while other etiologies did not exhibit differences. Patients with ACLF exhibit a higher MELD-Na score at admission (27 [22-31] versus 16 [12-21], p<0.0001) and a longer length of hospital stay (20 [10-33] versus 5 [3-9] days, p<0.0001) than cirrhotics without ACLF. Regarding precipitant factors at admission, patients with ACLF showed a higher infection incidence (39.1% versus 8.8%, p<0.0001) and acute kidney injury (AKI) (20.7% versus 1.3%, p<0.0001) than those without ACLF (Table 1). The main comparisons according to ACLF grade are described in Table 2. In particular, there was a trend for a higher length of hospital stay in patients with ACLF-3, but it was not statistically significant (p=0.130).

History of decompensation before admission. (A) The diagram shows the percentage of patients with ACLF and without ACLF who had a history of having had some decompensations. No significant differences were observed between the groups in the history of ascites (p=0.144); HE (p=0.139); EGVB (p=310); SBP (p=0.959); PVT (p=0.105) and SHR (p=850). (B) The figure shows the number of patients who had episodes of decompensation before admission according to the degree of ACLF. ns: no statistically significant; HE: hepatic encephalopathy; EGVB: esophageal varices bleeding; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; PVT: Portal vein thrombosis; HRS: hepato-renal syndrome.

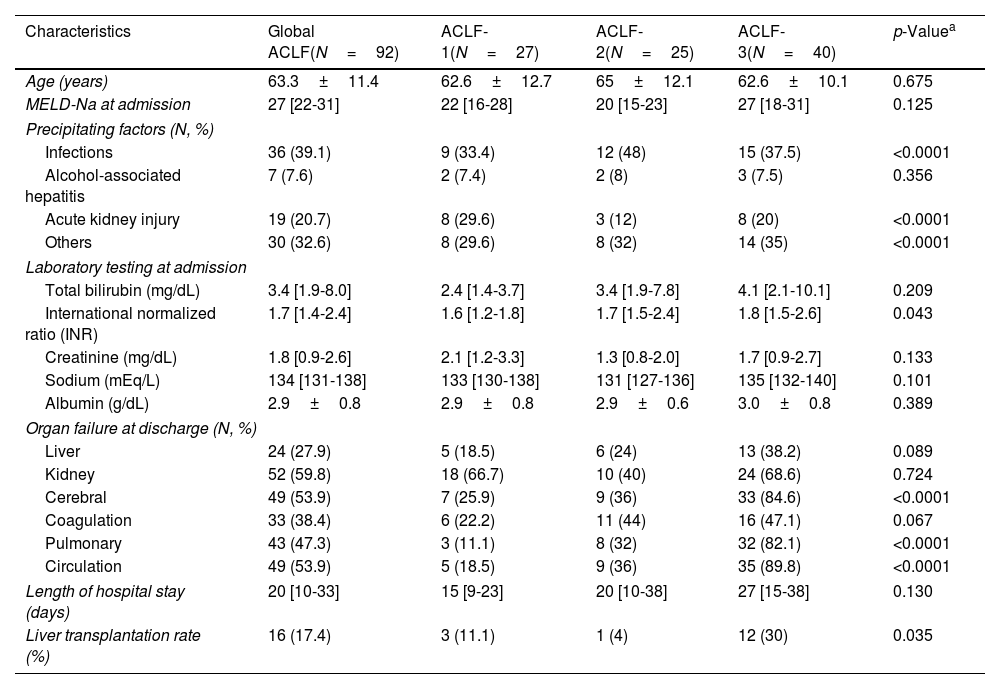

Characteristics of the patients who developed ACLF during admission according to ACLF grade.

| Characteristics | Global ACLF(N=92) | ACLF-1(N=27) | ACLF-2(N=25) | ACLF-3(N=40) | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.3±11.4 | 62.6±12.7 | 65±12.1 | 62.6±10.1 | 0.675 |

| MELD-Na at admission | 27 [22-31] | 22 [16-28] | 20 [15-23] | 27 [18-31] | 0.125 |

| Precipitating factors (N, %) | |||||

| Infections | 36 (39.1) | 9 (33.4) | 12 (48) | 15 (37.5) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol-associated hepatitis | 7 (7.6) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (8) | 3 (7.5) | 0.356 |

| Acute kidney injury | 19 (20.7) | 8 (29.6) | 3 (12) | 8 (20) | <0.0001 |

| Others | 30 (32.6) | 8 (29.6) | 8 (32) | 14 (35) | <0.0001 |

| Laboratory testing at admission | |||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.4 [1.9-8.0] | 2.4 [1.4-3.7] | 3.4 [1.9-7.8] | 4.1 [2.1-10.1] | 0.209 |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.7 [1.4-2.4] | 1.6 [1.2-1.8] | 1.7 [1.5-2.4] | 1.8 [1.5-2.6] | 0.043 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.8 [0.9-2.6] | 2.1 [1.2-3.3] | 1.3 [0.8-2.0] | 1.7 [0.9-2.7] | 0.133 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 134 [131-138] | 133 [130-138] | 131 [127-136] | 135 [132-140] | 0.101 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9±0.8 | 2.9±0.8 | 2.9±0.6 | 3.0±0.8 | 0.389 |

| Organ failure at discharge (N, %) | |||||

| Liver | 24 (27.9) | 5 (18.5) | 6 (24) | 13 (38.2) | 0.089 |

| Kidney | 52 (59.8) | 18 (66.7) | 10 (40) | 24 (68.6) | 0.724 |

| Cerebral | 49 (53.9) | 7 (25.9) | 9 (36) | 33 (84.6) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulation | 33 (38.4) | 6 (22.2) | 11 (44) | 16 (47.1) | 0.067 |

| Pulmonary | 43 (47.3) | 3 (11.1) | 8 (32) | 32 (82.1) | <0.0001 |

| Circulation | 49 (53.9) | 5 (18.5) | 9 (36) | 35 (89.8) | <0.0001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 20 [10-33] | 15 [9-23] | 20 [10-38] | 27 [15-38] | 0.130 |

| Liver transplantation rate (%) | 16 (17.4) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (4) | 12 (30) | 0.035 |

A total of 49.5% of patients had a history of alcohol intake, which was considered excessive in 52.7% of them. In addition, 27.7% of admitted patients had active alcohol intake, despite a prior diagnosis of cirrhosis. Active alcohol intake was more frequent in patients with ACLF (37.2% versus 23.8%, p=0.019). In the case of ALD, 50 (61%) patients had an active alcohol intake. The prevalence of active alcohol intake was also higher in patients with ALD who fulfilled ACLF criteria compared to those without ACLF (79% versus 49%, p<0.0001). Notably, a total of 17 (16.2%) patients with a prior diagnosis of NAFLD had active alcohol consumption, which was higher than the traditional threshold of alcohol intake defined for the diagnosis of NAFLD (Fig. 2).

Active alcohol consumption at admission according to etiology of cirrhosis. The graph shows the percentage of patients according to the etiology of their cirrhosis who at admission, despite having a diagnosis of cirrhosis, were still actively consuming alcohol. ALD: alcohol-associated liver disease; NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

In patients who developed ACLF, the kidney (52 patients, 59.8%) was the most frequent organ failure, followed by cerebral (49 patients, 53.9%), circulation (49 patients, 53.9%), lungs (43 patients, 47.3%), coagulation (33 patients, 38.4%) and liver failure (24 patients, 27.9%) (Table 2). In the analysis according to ACLF grade, in those with ACLF-1, kidney failure was the most frequent organ failure (as previously defined) (18 patients, 66.7%). In ACLF-2 an increase in coagulation failure was observed (11 patients, 44%), while in ACLF-3, circulation (35 patients, 89.8%), cerebral (33 patients, 84.6%), and lungs (32 patients, 82.1%) failure were very frequent, followed by kidney (24 patients, 68.6%), coagulation (16 patients, 47.1%) and liver (13 patients, 38.2%) failure (Fig. 3).

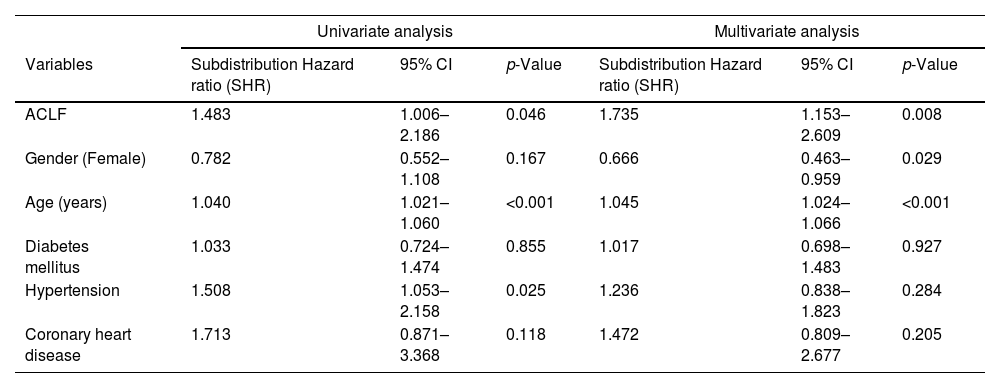

Long-term survival and liver transplantationA total of 43 patients with ACLF died during the follow-up. The result of the transplant-free survival curve through Kaplan–Meier analysis is presented in Fig. 4. We assessed survival according to the presence of ACLF using a competing-risk model. We performed a univariate analysis and then conducted a multivariate-adjusted model to improve the characterization of factors associated with mortality. In the univariate analysis, we observed that variables independently associated with mortality were ACLF (dichotomized) (SHR 1.483, 95%CI: 1.006-2.186; p=0.046), age (SHR 1.040, 95%CI: 1.021-1.060; p<0.001) and HTN (SHR 1.508, 95%CI: 1.053-2.158; p=0.025). In the multivariate-adjusted model, the presence of ACLF was associated with higher mortality (SHR 1.735, 95%CI: 1.153-2.609; p=0.008) (Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate competing risk analyses. Mortality is the primary event, and liver transplant is the competing risk.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Subdistribution Hazard ratio (SHR) | 95% CI | p-Value | Subdistribution Hazard ratio (SHR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

| ACLF | 1.483 | 1.006–2.186 | 0.046 | 1.735 | 1.153–2.609 | 0.008 |

| Gender (Female) | 0.782 | 0.552–1.108 | 0.167 | 0.666 | 0.463–0.959 | 0.029 |

| Age (years) | 1.040 | 1.021–1.060 | <0.001 | 1.045 | 1.024–1.066 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.033 | 0.724–1.474 | 0.855 | 1.017 | 0.698–1.483 | 0.927 |

| Hypertension | 1.508 | 1.053–2.158 | 0.025 | 1.236 | 0.838–1.823 | 0.284 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.713 | 0.871–3.368 | 0.118 | 1.472 | 0.809–2.677 | 0.205 |

In an accelerated failure time model to study the speed to the event (mortality), we performed a univariate analysis and then conducted a multivariate-adjusted modeling. In the univariate analysis, we observed that the presence of ACLF-1 at admission (time ratio [TR] 0.176, 95%CI: 1.006-2.186; p=0.046), increased age (TR 1.040, 95%CI: 0.532-0.582; p<0.004), ACLF-3 (TR 0.079, 95%CI: 0.023-0.266; p<0.001), and HTN (TR 0.506, 95%CI: 0.239-1.072; p=0.076) were associated with a faster time to death. In the multivariate-adjusted model, the presence of ACLF 1 or 2 was statistically different from patients without ACLF, both of which show a faster time to death (ACLF-1; TR 0.214, 95%CI: 0.075-0.6146; p<0.004), (ACLF-2; TR 0.224, 95%CI: 0.070-0.713; p<0.011). Patients with ACLF-3 criteria also showed a shorter time to event (TR 0.027, 95%CI: 0.006-0.129; p<0.001), evidencing higher mortality at a shorter time. Thus, developing ACLF-1 shortens the time to death by 4.7 times, ACLF-2 by 4.4 times, and ACLF-3 by 37 times (Table 4).

Results from the accelerated failure time model.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Time ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | Time ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

| ACLF grade 1 | 0.176 | 0.532–0.582 | 0.004 | 0.214 | 0.075–0.6146 | 0.004 |

| ACLF grade-2 | 0.395 | 0.113–1.382 | 0.146 | 0.224 | 0.070–0.713 | 0.011 |

| ACLF grade 3 | 0.079 | 0.023–0.266 | <0.001 | 0.027 | 0.005–0.128 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 1.822 | 0.871–3.813 | 0.111 | 2.364 | 1.11–4.61 | 0.025 |

| Age (years) | 0.933 | 0.903–0.965 | <0.001 | 0.926 | 0.895–0.957 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.793 | 0.3728–1.690 | 0.549 | 0.943 | 0.463–1.919 | 0.872 |

| Hypertension | 0.506 | 0.239–1.072 | 0.076 | 0.952 | 0.460–1.971 | 0.896 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.320 | 0.709–1.451 | 0.140 | 0.572 | 0.147–2.226 | 0.421 |

| Active alcohol use | 0.829 | 0.380–1.807 | 0.638 | 1.132 | 0.527–2.429 | 0.750 |

A total of 16 (17.3%) patients with ACLF were transplanted. The median time to transplant was 41 [2-490] days. Patients with ACLF-3 trended toward a higher rate of LT, compared to ACLF-1 and ACLF-2, although it was not statistically significant (30% versus 11.% versus 4%, respectively, p=0.035) (Table 2). LT was more frequent in patients who met ACLF-3 criteria (12, 13%). In the transplanted group, 7 (37%) had suspected or confirmed ALD etiology, 3 (18%) had variceal bleeding, 2 (12%) had SBP, and 14 (87%) had AKI. None of the patients who underwent LT died during follow-up.

DiscussionACLF is a clinical syndrome associated with elevated short-term mortality and healthcare costs. Although its evidence has grown exponentially during the last two decades, this entity has not been characterized adequately in Latin America. In this Chilean multicenter registry-based cohort study of 320 patients admitted for decompensated cirrhosis, we identified ACLF criteria in almost a third of patients. ALD was the most common etiology for patients who presented ACLF during admission. Also, patients with ACLF in our study had a higher frequency of kidney injury, as organ failure as well as a precipitating factor (along with infections). In our models, the presence of ACLF during hospitalization was associated with higher mortality (SHR 1.73) and a shorter time to death in a dose-dependent manner. Therefore, ACLF-1 shortens the time to death by 4.7 times, ACLF-2 by 4.4 times, and ACLF-3 by 37 times. As expected, the presence of ACLF was associated with higher rates of LT. Active alcohol intake was frequent in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, even those with diagnoses other than ALD.

Only a few studies in Latin America have characterized patients with ACLF and estimated the mortality of this entity.16 Most of these previous studies excluded severely ill patients and generally enrolled few participants. The ACLF incidence was 28.7% in our cohort, similar to that published in prior Latin American studies.17,18,20,21,31 However, the prevalence was lower than that reported in some European and Asian studies.16 This finding might be partly explained by some degree of under-reporting and due to diverse clinical and biochemical definitions of ACLF. Another reason is that Latin America, as a region, suffers from severe economic and cultural inequalities. Thus, potential healthcare access disparities for severely ill patients could bias that incidence.32,33 The lack of technical resources to reach the diagnosis (e.g., lack of access to laboratory tests and trained medical personnel) could also lead to under-report and under-identification of patients with ACLF. The combination of these factors probably leads to bias against less severe patients, which decreases the prevalence of ACLF in the region. In addition to confirming that patients with ACLF have higher mortality, they show a shorter time to death when evaluated using time-to-event models.

Previous publications have established that the presence of ACLF has a strong negative impact on long-term survival. We decided to use an AFT model instead of the Cox proportional hazards model to directly measure the effect of the explanatory variables on survival time instead of the hazard, as we do in the proportional hazards models. Given the high short-term mortality of patients with decompensated cirrhosis, this method can better evaluate mortality and, more importantly, time to death.29,30 The patients with ACLF, and more strongly patients with ACLF-3, presented a shorter time to event (TR 0.027). The findings of our time-to-event model are interesting since it emphasizes the importance that patients with ACLF-3 not only have higher mortality but, more worryingly, a faster time to death. Therefore, those patients who died in this event occurred very early after admission. These findings highlight the importance of early intensive management and raise the need for clear criteria to define ACLF and adequate therapeutic measures. In Latin America, patients with ACLF-3 since admission likely corresponds to extremely severe patients whose prognosis is defined at the time of arrival at the hospital.

The harmful consequences of alcohol use in liver disease are well-known globally.34,35 However, there is little data on the role of alcohol consumption in patients with ACLF, when it is not in the context of alcohol-associated hepatitis. In our study, patients with ALD have a higher incidence of ACLF than those patients with other etiologies. Also, the patients with ACLF, independent of etiology, had higher rates of active alcohol consumption at admission. It is of concern that 61% of the patients with a history of cirrhosis due to ALD and 17% of those with cirrhosis due to NAFLD had excessive alcohol consumption at admission. We evidenced a clear association between ACLF and alcohol consumption as expected, especially considering that acute and chronic alcohol consumption is associated with an abnormal immune response (altering leukocyte function and immune system activation at very different levels)36,37 and it may have some effect in the clinical course and outcome of these patients. Thus, all patients admitted for ACLF should undergo screening and assessment for alcohol use. Furthermore, it is crucial to evaluate alcohol consumption in all cirrhotic patients who are being monitored on an outpatient basis, either through clinical interviews or biomarkers, and to initiate treatment for AUD when deemed suitable

Infections are frequent in patients who develop ACLF. They correspond to one of the main triggering causes, and the presence of ACLF increases the risk of infection. In this group of patients, infections are usually severe and associated with poor clinical outcomes.38,39 In a study from Spain, that included 407 patients, 37% presented bacterial infections at the time of ACLF diagnosis, and of those who did not present infection at admission, 46% developed it the following four weeks. This group had higher mortality at 90 days (71%) compared to those who did not develop infections.38 Interestingly, in another study, survival at 30 days was lower in patients with ACLF triggered by bacterial infection than in patients with other decompensating factors (71.6% versus 33.8%, p<0.001). Furthermore, infection as a trigger was independently associated with increased mortality (OR 4.28).40 In the CANONIC study, it was found that 32.6% of patients had a bacterial infection as the trigger of ACLF. This percentage was found to be higher in patients with higher grades of ACLF. Specifically, the percentage of patients with a bacterial infection trigger was 29.9%, 30.8%, and 44.7% for ACLF-1, ACLF-2, and ACLF-3, respectively.3 Data regarding infections in ACLF in Latin America is conflicting. In a study from Brazil that included 43 patients with ACLF, only 3.4% presented infections (other than SBP) and 6.4% SBP.18 In the same country, a study reported that 50% of the patients with ACLF were admitted with a bacterial infection.20 In another study, only 5.6% had infections not corresponding to SBP, and 11.1% had SBP.17 In an Argentinean study including 29 patients with ACLF, bacterial infection was determined as a trigger factor in 41.3% of the patients.21 Finally, in a study developed in Peru that included 34 patients with ACLF, infections were triggering factors in 29% of the patients.31 Our results were similar to those published in other cohorts, infections at admission were very frequent in patients with ACLF (39.1% versus 8.8% in decompensated cirrhosis without ACLF, p<0.0001). They were similar to those published in series in Europe3 and Argentina.21 However, they were higher than studies published in Brazil17,18 and Peru. These differences may be attributed to the inclusion of patients with lower severity in these studies. These findings highlight the heterogeneity that exists between countries and even within the same country. This heterogeneity may be influenced by factors such as access to healthcare, diagnostic tools, and therapeutic resources.

It is well known that the development of AKI in patients with cirrhosis is associated with increased mortality and a worse prognosis.41–43 A study in Taiwan, which included 134 cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU, found a mortality of 32.1% in those without AKI. The authors used the RIFLE classification, which assesses the severity of renal failure based on plasma creatinine values and urine output, and classifies AKI into three severity classes: Risk, Injury, and Failure. In patients who met the criteria for AKI, the mortality was 68.8% in RIFLE-R, 71.4% in RIFLE-I, and 94.8% in RIFLE-F.44 A similar association was observed in a study in the UK, which included 412 cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU. Mortality increased from 42.5% in patients without AKI to 71% in RIFLE-R and 88% in RIFLE-I/F patients.45 Another study in the US involving 192 patients also found increased mortality dependent on the AKI stage, with a mortality of 2% for AKIN 1, 15% for AKIN 2, and 44% for AKIN 3 (independent of the admission ward).46

In patients with ACLF, AKI is frequent. The CANONIC study reported AKI in 13.2% and kidney failure in 55.8% of ACLF patients.3 Other studies based on APASL criteria reported kidney dysfunction in 22.8% and 51% of the patients.8,47,48 Studies have shown that the kidneys are affected differently in patients with decompensated cirrhosis without ACLF criteria than in patients with ACLF. Patients with ACLF more frequently present with AKI secondary to structural alterations, with a greater potential for reversibility, but with a higher rate of progression and higher mortality.49 In a study of post-mortem renal biopsies of patients with AKI and ACLF, evidence of structural compromise due to AKI was observed, unlike the functional alterations observed in patients with cirrhosis. Cholemic nephropathy (CN) was observed in 54%, acute tubular necrosis (ATN) in 31%, and a combination of CN and ATN in 15%.50 In our study, AKI was significantly higher in the group that developed ACLF versus cirrhotic patients without ACLF (20.7% versus 1.3%, p<0.0001). A large proportion of patients with ACLF-1 met ACLF criteria exclusively because of the presence of acute renal injury. It was present in 66% of patients with ACLF-1 and 68% of patients with ACLF-3. Interestingly, in patients with ACLF-1, despite AKI being the only organ failure, increased mortality was observed, which corroborates the importance of renal failure in cirrhotic patients and particularly in patients who develop ACLF.

Our study has several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the retrospective design limits our ability to control for confounding variables that may have influenced the results. Additionally, the use of registry-based data may introduce biases. Furthermore, the initial diagnosis of cirrhosis was not confirmed by biopsy, and the diagnoses of etiology and complications were mainly based on clinical data and medical records. Alcohol consumption was also self-reported, which may have led to inaccuracies. Although we recruited over 90 patients with ACLF, the number of patients who experienced the main outcome (mortality) or underwent liver transplantation was relatively small, which limited our ability to conduct subgroup analyses. It is important to note that Latin American countries have significant differences in access to healthcare and social characteristics. Therefore, new studies are necessary to characterize this region more thoroughly. Additionally, prospective studies should be conducted to evaluate the impact of different patterns of alcohol consumption on mortality in patients with ACLF in our region. This is especially important given the high rate of alcohol consumption in Latin America and its fundamental effect on liver disease.

In conclusion, our study of Chilean patients with decompensated cirrhosis highlights the high prevalence of alcohol consumption in this population. ACLF was a frequent occurrence in hospitalized patients, particularly those with ALD and a history of alcohol intake. Our results demonstrate that ACLF is associated with higher and faster mortality rates compared to those without ACLF. Additionally, AKI was the most common organ dysfunction observed in our cohort. To improve patient outcomes, efforts should be made to promote alcohol abstinence in all patients with cirrhosis, regardless of the underlying etiology. Future prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings and guide clinical management.

Authors’ contributionsAuthors confirm contribution to the article as follows: Francisco Idalsoaga: Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing. Luis Antonio Diaz: Conceptualization, Writing - Review and Editing. Eduardo Fuentes-López: Analyzed the data, Review and Editing. Gustavo Ayares: Writing - Review and Editing. Francisco Valenzuela: Conceptualization, Writing - Review and Editing. Victor Meza: Recruitment and Writing. Franco Manzur: Recruitment and Writing. Joaquín Sotomayor: Recruitment and Writing. Hernán Rodriguez: Recruitment and Writing. Franco Chianale: Recruitment and Writing. Sofía Villagran: Recruitment and Writing. Maximiliano Schalper: Recruitment and Writing. Pablo Villafranca: Recruitment and Writing. Maria Jesus Veliz: Recruitment and Writing. Paz Uribe: Recruitment and Writing. Maximiliano Puebla: Recruitment and Writing. Pablo Bustamante: Recruitment and Writing. Herman Aguirre: Recruitment and Writing. Javiera Busquets: Recruitment and Writing. Juan Pablo Roblero: Writing - Review and Editing. Gabriel Mezzano: Writing - Review and Editing. Maria Hernandez-Tejero: Writing - Review and Editing. Marco Arrese: Writing - Review and Editing. Juan Pablo Arab: Conceptualization, Writing - Review, Editing and Supervision.

Data availability statementThe datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial supportThis article was partially supported by the Chilean government through the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT 1200227 to JPA and 1191145 to MA); and research funds for residents/fellows from P. Universidad Católica de Chile.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.