Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is often linked to sleep problems, but previous studies on sleep abnormalities in AUD have produced inconsistent results. This study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of objectively measured sleep abnormalities in AUD and determine the impact of related and demographic factors on sleep disturbance.

MethodsWe conducted a comprehensive search of several databases from 1968 to 2023 to identify relevant studies. A total of 12 studies, consisting of 13 datasets, were included in the analysis. We extracted information on sleep microarchitecture, as well as demographic and clinical features, from each study. The GRADE approach was used to assess the reliability and strength of the evidence.

ResultsPatients with AUD exhibited several sleep abnormalities, including longer sleep onset latency, lower sleep efficiency, increased stage 1 sleep, decreased stage 2 sleep, reduced slow wave sleep, and elevated rapid eye movement (REM) sleep density and first REM minute. The sleep patterns in individuals with AUD were also influenced by factors such as ethnicity, age, gender, and abstinence period.

ConclusionsThis study is the largest quantitative assessment of impaired sleep as a diagnostic marker in patients with AUD. Understanding the sleep patterns of individuals with AUD can assist clinicians in developing effective treatment plans for managing sleep-related symptoms associated with AUD.

Alcohol is one of the most commonly used psychoactive substances worldwide. Reportedly, about 50% of adult respondents consume alcohol, of whome some indulge in heavy drinking.1 The heavy drinking pattern is prevalent among individuals suffering from alcohol use disorder (AUD) or alcohol dependence disorder (AD), which is linked to a higher incidence of medical and mental health conditions characterized by sleep disturbance.2

According to the Rechtschaffen and Kales (R&K) standardized scoring system described in 1968, sleep is comprised of two states: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep (NREM), which can be further dissected into four stages (S1–4).3 S1, the lightest stage and always considered a measure of sleep quality, is commonly known as light NREM sleep (N1). During this stage, individuals experience fluctuations in consciousness. S2, also referred to as N2, is a distinct sleep stage characterized by the presence of sleep spindles and K-complexes. This stage makes up approximately 45–55% of the sleep cycle. S3 and S4, collectively known as slow wave sleep (SWS) or N3, represent a phase of deep restorative sleep. Sleep typically starts with N1 and progresses towards deeper stages of NREM until the first period of REM sleep is reached. Afterwards, REM and NREM sleep alternate in cycles lasting about 90 min. The states of sleep are regulated by homeostasis, meaning that a lack of REM or SWS triggers a need to enter that stage, and once it begins, there is an increased intensity of that stage to compensate for the deprivation.

Among patients with AUD, the rate of sleep disturbance is higher than that in the general population.4 The correlation between sleep disturbance and AUD is bidirectional. Alcohol is often used as a sleep aid, and it can have either a stimulating or sedating effect, inducing sleep.56 Stimulating effects are commonly observed at lower doses as blood alcohol levels increase, typically within the first hour following consumption. Conversely, sedating effects manifest at higher doses and as blood alcohol levels gradually decrease. Instead of seeking professional treatment, many adolescents and adults suffering from insomnia often resort to using alcohol as a means to induce sleep, only to experience adverse effects and unintentionally worsen their condition.7 Mounting evidence suggests that alcohol consumption significantly disrupts sleep patterns, particularly by affecting REM, SWS as well as sleep duration, latency, and continuity.8 The net effect of an intoxicating alcohol dose is to worsen sleep by increasing awakeness after sleep onset (WASO) and reducing sleep onset latency (SOL).9-11 Therefore, the persistent use of alcohol can be deemed a counterproductive long-term approach, as it not only hampers the quality of sleep but also exacerbates the urge to consume excessive amounts of alcohol. Furthermore, individuals who are dependent on alcohol commonly encounter sleep difficulties not only while actively drinking but also during different phases of abstinence, such as acute, subacute, or chronic periods.12-14 Consequently, increasing clinical awareness of sleep problems as a symptom of AUD can potentially enable prompt intervention and timely treatment.

Polysomnography (PSG) is an objective method to derive quantitative sleep measures and record electroencephalogram, electrooculogram, and electromyogram. PSG can provide detailed examination of sleep macroarchitecture, which refers to the latencies and durations of sleep stages.15 To date, numerous studies have used PSG to understand the neurobiology of AUD. Using PSG, these studies have documented sleep disturbances in individuals with AUD compared to healthy controls, which include abnormalities in TST, sleep onset latency (SOL), sleep efficiency (SE), S1, SWS, REM sleep, REM sleep latency (REML), and REM sleep density (REMD).16-18 It is worth mentioning that a number of past studies have relied on subjective self-report measures to define "sleep problems" but did not find a significant association between alcohol use and insomnia.19,20 As a result, there is a need for a comprehensive analysis of objective sleep measures in order to provide a more accurate understanding of the relationship between alcohol use and sleep disturbances.

The present study aimed to examine the comprehensive pattern of objectively measured sleep abnormalities in individuals with AUD by synthesizing previous relevant research findings. In addition, moderator analysis was used to identify potential variables that could influence the sleep features of AUD. We hypothesized that individuals with AUD would exhibit impaired sleep continuity and PSG characteristics compared to healthy controls, with variations in clinical and methodological factors moderating the heterogeneity observed among the studies.

MethodsDesign and registrationThis review was conducted according to the registered protocol PROSPERO CRD42022344827 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.21

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were as follows: (1) Participants: individuals with AUD, alcohol abusers, or chronic heavy alcohol users; (2) Intervention: sleep parameters were assessed using PSG; (3) Comparison groups: a non-using or limited use group; (4) Outcomes: means and standard deviations of TST, SOL, SE, WASO, S1/N1, S2/N2, SWS/N3, REM, REML, REMD, and 1st REM min; (5) Type of studies: case-control studies conducted in English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participants with any other severe neurological or mental disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV); (2) studies conducted on animals; (3) studies that did not use the R&K or the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) criteria for PSG scoring; (4) studies that duplicated previous publication(s); (5) studies in which essential data were unavailable from the corresponding author through email. The inclusion of the studies was determined by two independent investigators, and any disputes were resolved through discussion.

Search strategiesA literature search was conducted on PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, MedLine, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane from 1968 to 2023, without any date restrictions. The following keywords were used: (“alcohol” OR “ethanol abuse” OR “alcoholism” OR “alcohol dependence” OR “alcohol addiction” OR “alcohol abuse” OR “alcohol use disorder”) AND (“sleep” OR “sleep disturbance” OR “polysomnography” OR “PSG” OR “REM” OR “slow wave sleep” OR “slow wave activity” OR “NREM sleep” OR “delta sleep” OR “sleep macroarchitecture”). The final literature searches were conducted in May 2023. The retrieved studies were then reviewed and duplicates were removed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to select appropriate articles. The titles, abstracts, keywords, and full texts of the retrieved studies were reviewed to exclude irrelevant articles. Additionally, the reference lists of the retrieved studies and recent reviews were manually checked to identify any additional studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Quality assessmentIncluded studies were assessed for methodological quality and the putative risk of bias using the validated Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which evaluates the non-randomized trials consisting of cohort and case-control studies.22

Data extractionThe following demographic information was obtained from eligible studies in this meta-analysis: the first author's name, publication year, number of participants, number of male participants, mean age, ethnicity, and years of education. The illness-related information included diagnostic tools, length of dependence, duration of abstinence, drinks per day, and drinking days per month. Mean effect measures and their standard deviation were then extracted, including TST, SOL, SE, WASO, REML, REMD, 1st REM min, and the proportion of S1, S2, SWS, and REM. Two independent reviewers extracted the data and any discrepancies in the results were resolved through discussion. A third independent reviewer assessed the coding for accuracy by randomly selecting and recoding five articles and examining potential outliers in the data. In cases of missing data, corresponding authors were contacted via email. If no feedback was received, studies with missing information were excluded.

Data analysisFor each measure, we calculated Cohen's d in accordance with the standard systematic approach on the platform (http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/resources/effect-size-input.php), using means and standard deviations or standard errors whenever feasible. Occasionally, F, t, or p-values were used along with the sample size to estimate the effect size. The magnitude of the difference between groups was expressed using hen's d which is a measure of effect size. This parameter indicates the extent to which the dependent variable is present in the sample group or the extent to which the null hypothesis is false. Due to the expected variability resulting from demographic characteristics and inclusion and exclusion criteria, we employed the random effects model to determine the overall effect size. To address the issue of overestimating the effect size associated with small sample sizes, Hedge's correction was applied to each effect size. Additionally, the inverse variance weights for each study were calculated using the corrected effect size.23

Heterogeneity was tested using Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic.24 A significant Q indicated substantial differences between the studies contributing to the pooled effect size. I2 was used as a second measure of heterogeneity of effect size representing within-study heterogeneity expressed as a percentage of the total variation across studies. In this study, we considered lack of statistical heterogeneity for 0≤I2<25%, low for 25%≤I2<50%, moderate for 50%≤I2<75%, and high for 75%≤I2. The publication bias was checked using the funnel plot and Egger's tests.25 Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out method to examine the influence of each study on the synthesized effect size in the random effects model.26

After calculating the overall effect size, Hedge's g was computed as the effect size for the moderator analysis, which included both categorical and continuous moderators.27,28 The planned subgroup analysis for categorical moderators included the following pre-defined categories: ethnicity (African, European, and Mixed),29,30 age (< 40, > 40),31 sample size (small < 40, large ≥ 40), gender composition (male, mixed, and female), diagnostic system (DSM-IV, DSM-III-R, and others) and duration of abstinence (short-abstinence period ≤ 1 month and long-abstinence period > 1 month).32 On the other hand, meta-regression analysis was used to examine whether the pre-defined quantitative moderators could influence the effect size. These included education years, length of dependence, drinks per day, and drinking days per month. To ensure that all participants fell within the range of the moderators, the distribution was examined rather than just the mean. All statistical analyses were performed using the R package "meta".

Assessment of cumulative evidenceThe quality of evidence for each outcome across studies was evaluated using four levels of confidence (high, moderate, low, or very low confidence) according to the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria.33

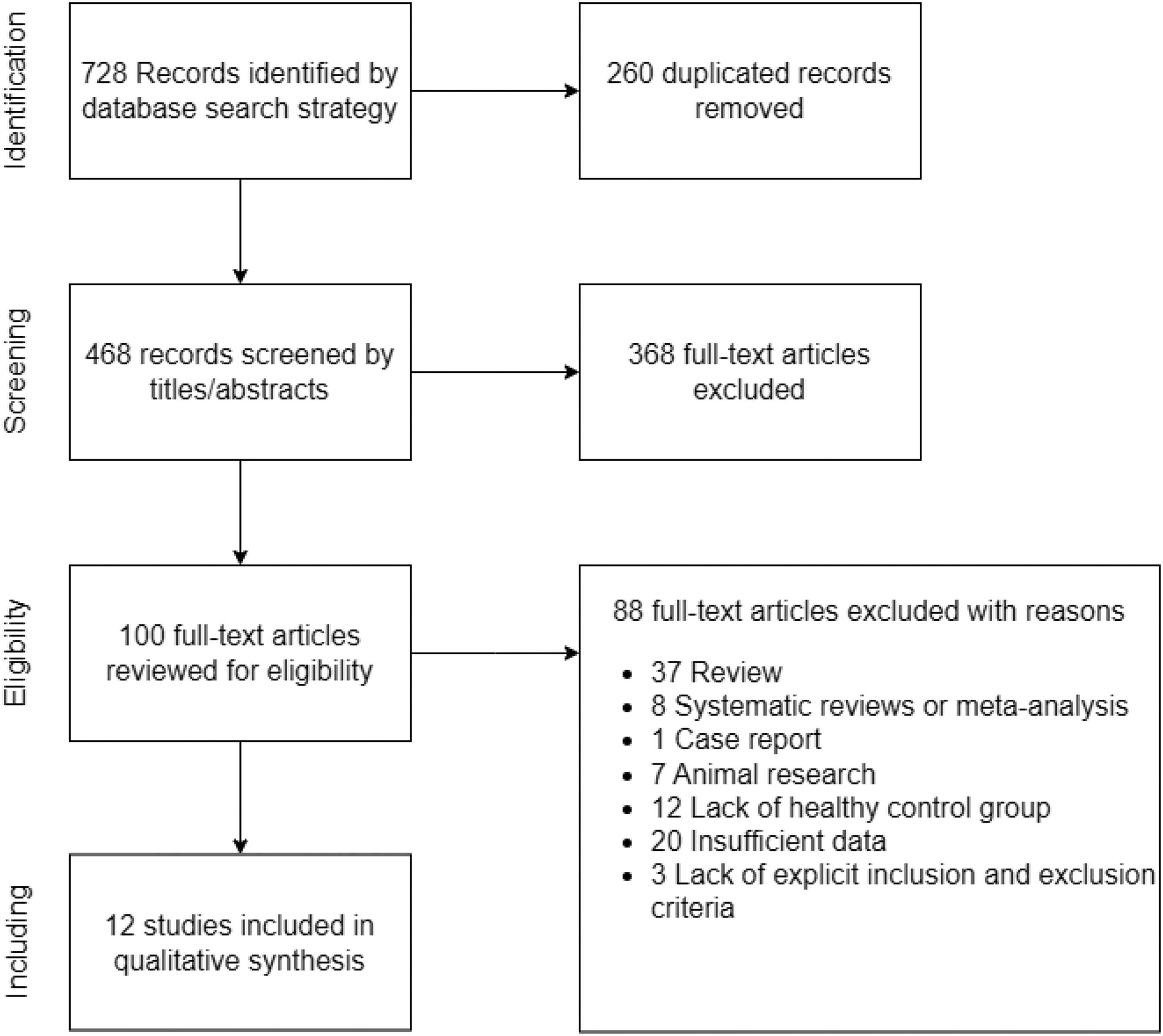

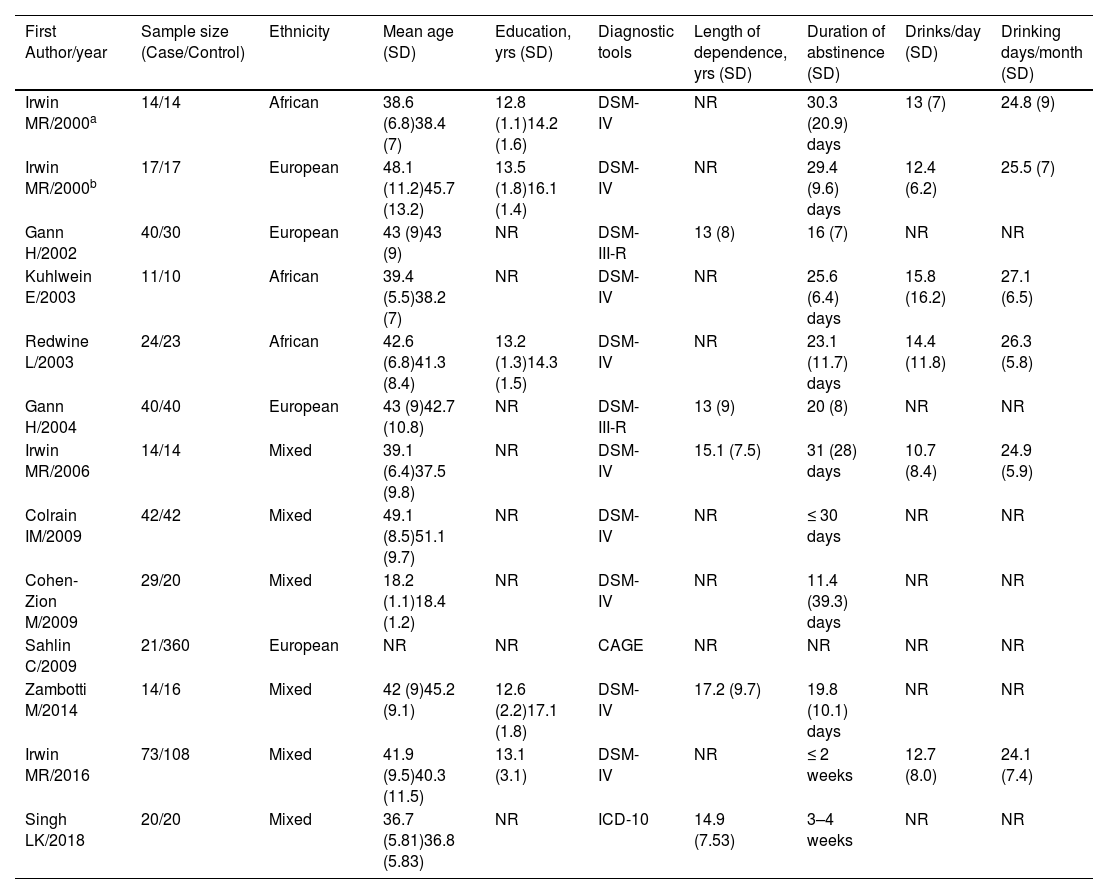

ResultsCharacteristics of included studiesA total of 13 datasets from 12 studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in this meta-analysis.16-18,34-42 The study by Irwin et al. (2000) consisted of two case groups.34 A summary of the screening process is presented in Fig. 1. The cohort comprised 359 patients with AUD (283 males/76 females) and 714 healthy controls (286 males/428 females). Other demographic and clinical information for each study is presented in Table 1. In addition, the methodological quality of the studies assessed by NOS is summarized in the Supplementary materials. Most of the included studies were scored ≥ 6 stars, and hence rated high quality.

Demographic and clinical information of studies included.

Abbreviations: %, percentage; CAGE, the cut down, annoyed by criticism, guilty about drinking and eye-opener drinks questionnaire; DSM-III/DSM-IV, third/fourth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; ICD-10, the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; No., number; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation; yrs, years.

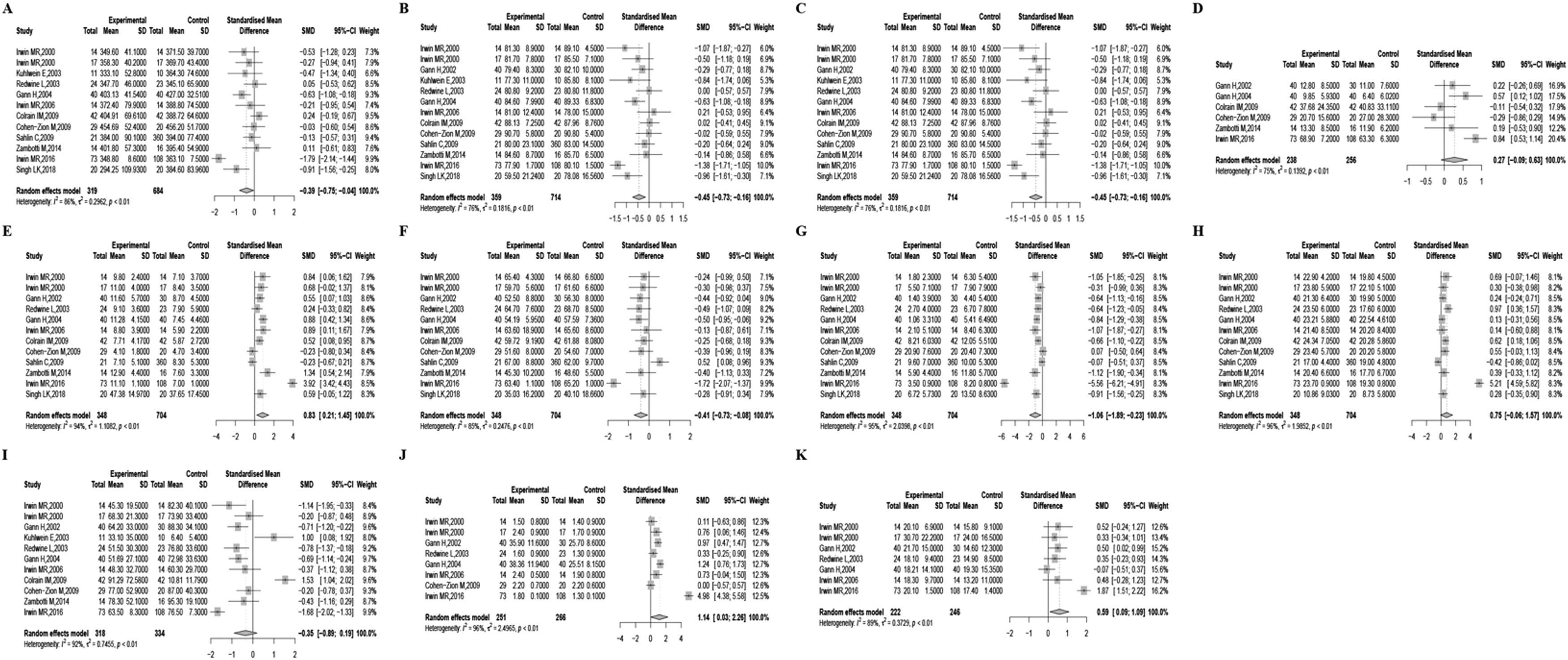

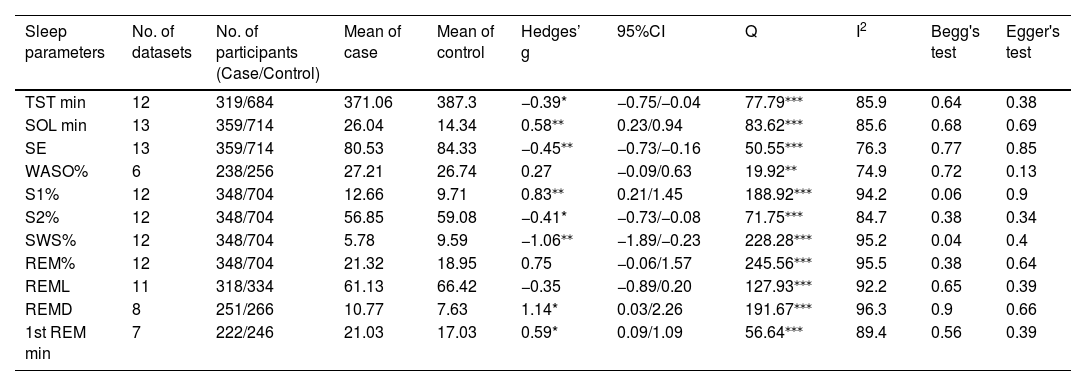

Due to moderate heterogeneity, we used the random-effects model to synthesize the pooled effect size. Patients with AUD exhibited several sleep-related alterations compared to non-dependent individuals. They experienced decreased TST, increased SOL, decreased SE, increased S1%, decreased S2%, decreased SWS%, increased REMD, and increased 1st REM min. Significant heterogeneity was noted in all results except for WASO%, REM%, and REML. To provide specific details concerning the pooled effect sizes and heterogeneity, please refer to Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Summary of meta-analyses.

| Sleep parameters | No. of datasets | No. of participants (Case/Control) | Mean of case | Mean of control | Hedges’ g | 95%CI | Q | I2 | Begg's test | Egger's test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST min | 12 | 319/684 | 371.06 | 387.3 | −0.39* | −0.75/−0.04 | 77.79⁎⁎⁎ | 85.9 | 0.64 | 0.38 |

| SOL min | 13 | 359/714 | 26.04 | 14.34 | 0.58⁎⁎ | 0.23/0.94 | 83.62⁎⁎⁎ | 85.6 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| SE | 13 | 359/714 | 80.53 | 84.33 | −0.45⁎⁎ | −0.73/−0.16 | 50.55⁎⁎⁎ | 76.3 | 0.77 | 0.85 |

| WASO% | 6 | 238/256 | 27.21 | 26.74 | 0.27 | −0.09/0.63 | 19.92⁎⁎ | 74.9 | 0.72 | 0.13 |

| S1% | 12 | 348/704 | 12.66 | 9.71 | 0.83⁎⁎ | 0.21/1.45 | 188.92⁎⁎⁎ | 94.2 | 0.06 | 0.9 |

| S2% | 12 | 348/704 | 56.85 | 59.08 | −0.41* | −0.73/−0.08 | 71.75⁎⁎⁎ | 84.7 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| SWS% | 12 | 348/704 | 5.78 | 9.59 | −1.06⁎⁎ | −1.89/−0.23 | 228.28⁎⁎⁎ | 95.2 | 0.04 | 0.4 |

| REM% | 12 | 348/704 | 21.32 | 18.95 | 0.75 | −0.06/1.57 | 245.56⁎⁎⁎ | 95.5 | 0.38 | 0.64 |

| REML | 11 | 318/334 | 61.13 | 66.42 | −0.35 | −0.89/0.20 | 127.93⁎⁎⁎ | 92.2 | 0.65 | 0.39 |

| REMD | 8 | 251/266 | 10.77 | 7.63 | 1.14* | 0.03/2.26 | 191.67⁎⁎⁎ | 96.3 | 0.9 | 0.66 |

| 1st REM min | 7 | 222/246 | 21.03 | 17.03 | 0.59* | 0.09/1.09 | 56.64⁎⁎⁎ | 89.4 | 0.56 | 0.39 |

p< 0.001.

Abbreviations: %, percentage; CI, confidence interval; min, minutes; Q, Cochran's Q statistic; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; REMD, rapid eye movement sleep density; REML, rapid eye movement sleep latency; S1, stage 1; S2, stage2; SE, sleep efficiency; SOL, sleep onset latency; SWS, slow wave sleep; TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake after sleep onset.

Forest plots describing the features of sleep macroarchitecture. Features of sleep macroarchitecture include (A) total sleep time, (B) sleep onset latency, (C) sleep efficiency, (D) wake after sleep onset, (E) stage 1, (F) stage 2, (G) slow wave sleep, (H) rapid eye movement sleep, (I) rapid eye movement sleep latency, (J) rapid eye movement sleep latency, (K) 1st rapid eye movement sleep minutes.

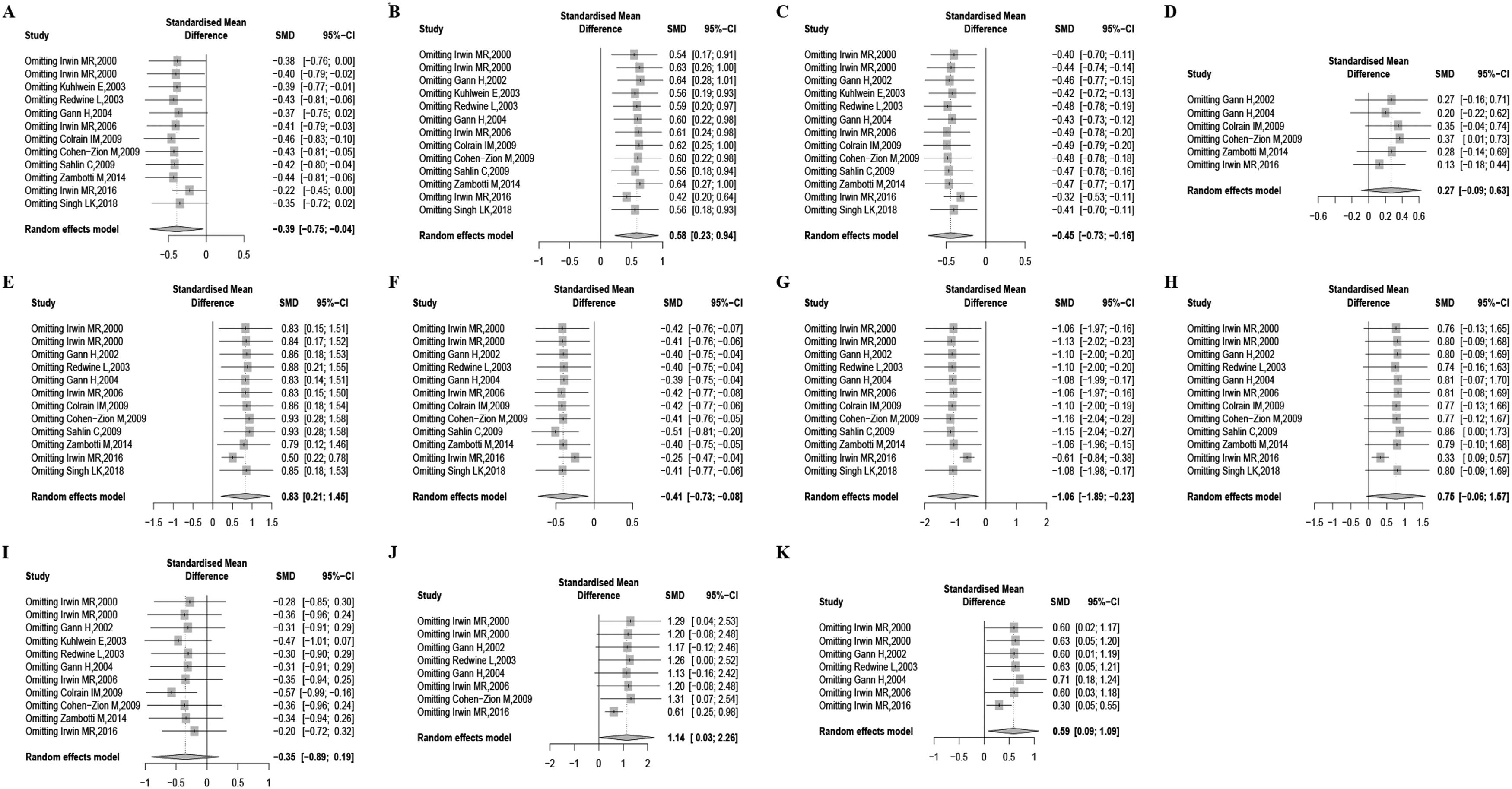

To evaluate the influence of outliers, we examined the standardized residual across all studies. Furthermore, we performed a sensitivity analysis by systematically removing one study at a time to assess the impact of individual studies on the pooled SMDs. The results revealed a reduction in heterogeneity for TST (I2=33.5), SOL (I2=44.0), SE% (I2=37.4), WASO (I2=43.7), N1% (I2=61.7), N2% (I2=31.5), SWS% (I2=43.2), REM% (I2=48.7), REMD (I2=61.9), and 1st REM min (I2=0) after excluding the study conducted by Irwin et al. (2016). However, even after removing the outlying study, the effect sizes for SOL (p<0.001), SE% (p<0.001), N1% (p<0.001), N2% (p<0.05), SWS% (p<0.001), REMD (p<0.001), and 1st REM min (p<0.001) remained significant. In contrast, the results for TST and REM% exhibited inconsistency. The detailed results are referred to in Fig. 3.

Results of “one-study removed” sensitivity analysis for all studies included on the features of sleep macroarchitecture. Features of sleep macroarchitecture include (A) total sleep time, (B) sleep onset latency, (C) sleep efficiency, (D) wake after sleep onset, (E) stage 1, (F) stage 2, (G) slow wave sleep, (H) rapid eye movement sleep, (I) rapid eye movement sleep latency, (J) rapid eye movement sleep latency, (K) 1st rapid eye movement sleep minutes.

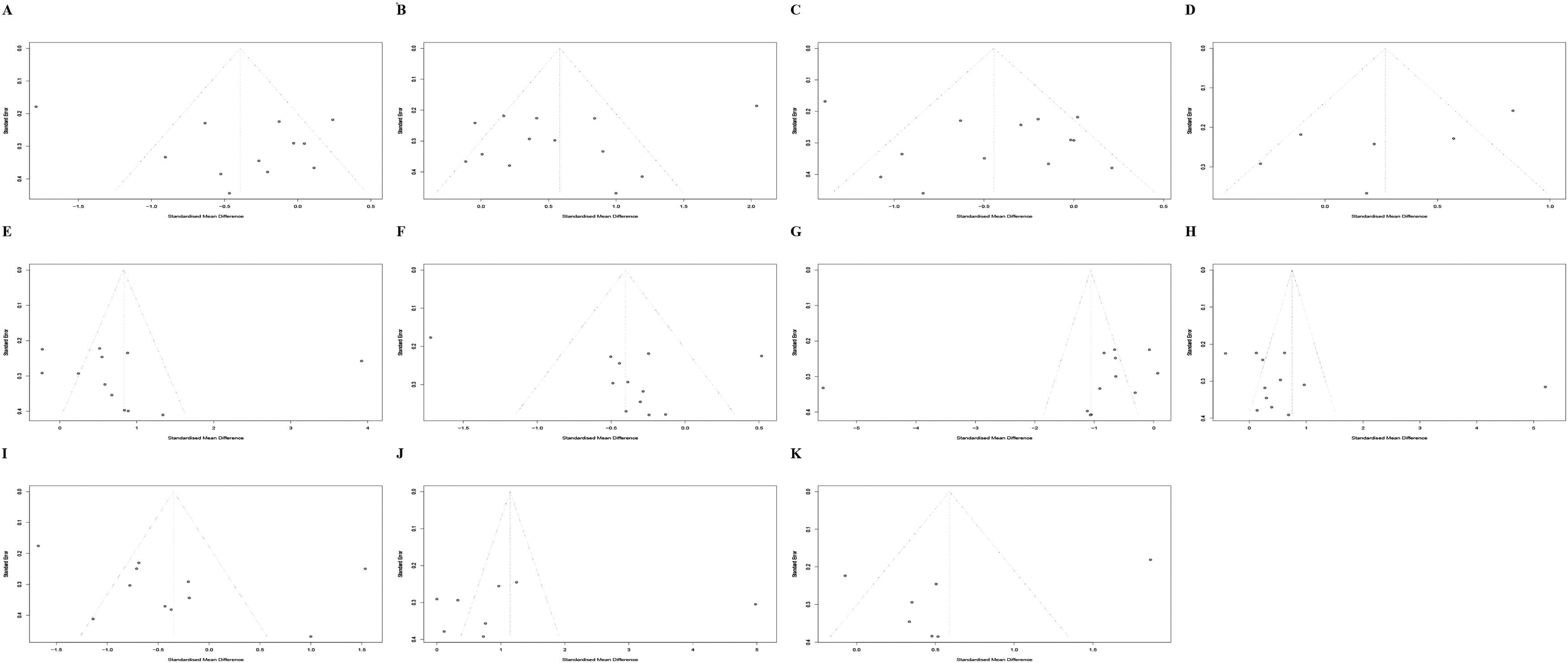

Funnel plots, Begg's test, and Egger's test were used to reveal the possible publication bias. The results indicate that there is no overestimation of the parameters (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

Funnel plots describing the spread of studies on the features of sleep macroarchitecture. Features of sleep macroarchitecture include (A) total sleep time, (B) sleep onset latency, (C) sleep efficiency, (D) wake after sleep onset, (E) stage 1, (F) stage 2, (G) slow wave sleep, (H) rapid eye movement sleep, (I) rapid eye movement sleep latency, (J) rapid eye movement sleep latency, (K) 1st rapid eye movement sleep minutes. Asymmetry in funnel plots represents publication bias.

Despite their high methodological quality, direct evidence, and precision, the studies included in the analysis exhibited moderate heterogeneity. As a result, the existing evidence to comprehend the sleep characteristics in AUD was deemed of very low quality based on the GRADE rating system (see Supplement materials).

Moderator analysisIn the subgroup analysis of ethnicity, it was found that African patients with AUD exhibited increased SOL, decreased SWS%, and increased REM% compared to healthy controls. On the other hand, European patients showed decreased SE, increased WASO, decreased SWS, decreased REML, and increased REMD in comparison to the healthy controls. Regarding age-based subgroup analysis, younger patients showed an increase in SOL and REM% while experience a decrease in SWS%. On the other hand, older patients exhibited an increase in WASO and S1% along with a decrease in SE, S2% and SWS. In the subgroup analysis based on sample size, we observed that studies with smaller sample sizes showed higher S1%, lower SWS%, higher REM%, longer REMD, and longer 1st REM min. Conversely, studies with larger sample sizes recorded lower. When considering the subgroup analysis according to DSM-IV criteria, it was found that patients exhibited increased SOL, WASO, and 1st REM min but decreased S2% and SWS%. Male patients had shorter TST, longer SOL, lower SE%, higher S1%, lower S2%, lower SWS%, higher REM%, longer REMD, and longer 1st REM min compared to female patients. In the subgroup analysis based on the duration of abstinence, patients with a long abstinence period had higher S1%, lower SWS%, and higher REM%, while patients with a short abstinence period had shorter TST, longer SOL, lower SE%, higher S1%, lower S2%, lower SWS%, and shorter REML. According to the meta-regression results, the effect size remained unaffected by the pre-defined moderators. These findings are presented in the Supplementary materials.

DiscussionThe present study, which is the first meta-analysis of polysomnographic studies, examines the differences in sleep architecture between individuals with and without AUD. In total, 13 datasets were analyzed to investigate the effects of AUD on 11 sleep parameters, including TST, SOL, SE, WASO%, S1%, S2%, SWS%, REM%, REML, REMD, and 1st REM min. In addition, preliminary comparisons were conducted for six potential categorical moderators, namely ethnicity, age, sample size, gender composition, diagnostic tools, and duration of abstinence. In terms of each sleep parameter, the overall mean effect sizes indicated that individuals with AUD exhibited higher levels of N1 sleep but lower levels of N2 and SWS sleep in comparison to healthy controls. Moreover, patients with AUD had greater SOL, REMD, and 1st REM min but shorter TST and SE. The high coexistence of insomnia and AUD may be due to unfavorable sleep habits and irregular sleep-wake schedules that inevitably arise from drinking.43 Changes in brain structure, function, and neurochemistry may also play a pivotal role in the aforementioned comorbidities.44 Strikingly, the occurrence of insomnia in individuals with AUD has been reported to be approximately 91%.45 Additionally, these individuals often experience poor SE and reduced SWS.On the other hand, they have elevated SOL, WASO, and stage N1 sleep. It has also been observed that abstinent AUD patients exhibit a rebound in REM sleep.14,46-48 Furthermore, the sleep disturbance of patients with AUD during the recovery period persists for several months to years following the last instance of alcohol use, and gradually improves over time.49 Therefore, previous findings partially support our results of centrally measured hyperarousal during sleep in patients with AUD.

Ethnicity is a significant factor associated with AUD. The prevalence of alcohol use in adults is higher among Caucasians than among African-Americans.1 Caucasians are inherently at a higher risk than African-Americans for developing AUD throughout their lives, according to research.50 However, once alcohol dependence occurs, African-Americans have a higher prevalence than Caucasians of recurrent or persistent alcohol dependence in their native population.51 African-American adult drinkers are disproportionately more likely to report symptoms of alcohol dependence and experience social consequences as a result of their drinking compared to Caucasian drinkers.52 The ethnic disparities in alcohol problems can be attributed to social and cultural factors. According to reports, both individual and neighborhood level economic disadvantage have been found to predict lower rates of alcohol treatment completion and higher alcohol consumption among Blacks compared to Whites. The ethnic discrimination against African-Americans is linked to significant severity of AUD in the USA, regardless of their specific ethnic group affiliation or poverty status.53 Previous studies have suggested that sleep-disordered breathing and insomnia may be more prevalent and severe among African-Americans compared to Caucasians.54 However, the results of a meta-analysis indicated that African-Americans took longer to fall asleep and had lighter sleep with more N2 and less SWS in comparison to Caucasians.55 Therefore, African-American patients with AUD may be more prone to sleep disturbances and experience more sleep problems compared to European-American patients. In the present study, it was found that African-American patients had higher sleep onset latency (SOL) and rapid eye movement (REM) percentage, but lower slow wave sleep (SWS) percentage, while European-American patients had decreased sleep efficiency (SE) and altered REM parameters (REML and REMD). Although direct comparison between African-American and European-American patients was not possible in this study, it suggests that ethnic differences independently contribute to sleep disturbances in individuals with AUD.

Few studies have investigated the influence of sex differences on the impact of drinking to intoxication, withdrawal, and protracted abstinence on sleep. Studies have shown that there are sex differences in drinking patterns and the way alcohol is processed in the body. For instance, women typically have less body water and more body fat compared to men. As a result, women often experience higher blood alcohol levels than men after consuming the same amount of alcohol due to its hydrophilic properties.56 Historically, AUD has been more prevalent among men than women. However, the gender gap in both alcohol consumption and AUD is decreasing.57 Women with AUD typically have lower quality-of-life scores compared to men with the disorder.58 However, no sexual differences were observed in the frequency of insomnia among men and women who received treatment for AUD.4 Colrain et al. reported that women exhibited higher SE and more delta activity during NREM sleep compared to men, irrespective of diagnosis. They also found that men diagnosed with AUD showed a more substantial decrease in delta activity during NREM sleep compared to women with AUD.39 In this study, we observed increased SOL, N1%, REM%, REMD, and 1st REM min, but decreased TST, SE, N2%, and SWS% in male patients with AUD, which aligns with previous findings. However, studies that included both male and female patients demonstrated a decrease in N2 and SWS sleep. We hypothesized that female patients may experience problems with NREM sleep. Unfortunately, due to the scarcity of research on female patients with AUD, we could not thoroughly analyze sex differences. Given the increasing prevalence of AUD in women, it is crucial for future studies to include large samples of both men and women with AUD to better understand potential gender-related differences in the impact of heavy drinking, alcohol withdrawal, and prolonged abstinence on sleep.

Age is a critical factor related to AUD and sleep.59 Several studies have shown a clear decline in alcohol consumption as individuals age. The period of highest consumption typically falls between the ages of 20 and 40, while rates of alcohol abuse are more prevalent among young people and those in middle age.60 Some elderly individuals claim that smaller doses of alcohol have a stronger perceived effect, as they may not socialize as much in settings where drinking is common or simply have a decreased desire to drink. Others develop a distaste for the taste and effects of alcohol as they age. Some mentioned giving up alcohol due to poor health or financial reasons.31 Compared to younger individuals, older alcoholics are much more likely to have significant medical problems, including sleep issues. Typical symptoms of sleep problems in elderly patients with AUD include difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep, early morning awakening, and excessive daytime sleepiness.61 Thus, the elderly population with AUD exhibited a decrease in prevalence but experienced more severe symptoms of sleep disturbances. Our findings indicated that younger patients with AUD experienced issues with SOL, SWS%, and REM%, whereas older patients primarily experienced problems with SE and NREM sleep. Generally, as individuals age, the deeper stages of NREM sleep are often reduced or absent. However, REM sleep tends to be preserved, which aligns with our study results.

The present study also investigated the effects of abstinence periods on sleep disturbance in individuals with AUD. Abnormal sleep patterns in patients with AUD continue for several months or even years during the recovery and abstinence process. Even after one to two years of quitting drinking, sleep tends to remain short, shallow, and fragmented.62 Reportedly, TST, SOL, SE, SWS%, and REML improved slowly by the end of 1–2 weeks of abstinence, but REM% remained elevated in most patients with AUD even after more than 1 year of abstinence.48,63,64 The latest findings have shown that patients with AUD who had short periods of abstinence exhibited abnormal sleep parameters, such as TST, SOL, SE, and NREM%, as well as decreased SWS sleep and increased REM sleep. The heightened REM sleep observed during withdrawal could be interpreted as a "REM sleep rebound".6

Several previous studies have indicated that the impact of alcohol on sleep is influenced by the amount consumed and works in both directions.6 Specifically, lower doses of alcohol have been shown to potentially enhance TST. On the other hand, higher doses of alcohol have been linked to reduced REM sleep and heightened SWS.9 Despite this, our study did not find any correlation between the amount of alcohol consumed and its impact on sleep for individuals with AUD. A possible reason that may have contributed to the results is that all the patients included are AUD patients with high alcohol consumption. This specific population could have unique physiological and psychological responses to alcohol that could impact the results. Other reasons include a potential lack of an adequate sample size, as well as individual differences that were not accounted for in the study, such as individual tolerance levels and timing of consumption.

The sensitivity analysis results revealed that the study conducted by Irwin et al. heightened the heterogeneity of the majority of the findings.17 The patients with AUD from the study were non-treatment-seeking, a characteristic that distinguished them from the participants in other studies that were included. Consequently, these patients had a shorter period of abstinence, suggesting that their clinical symptoms, such as sleep problems, were more severe. This disparity in symptom severity can be considered as the primary factor contributing to the observed heterogeneity. On the other hand, the results of SOL, SE, N1, N2, SWS, REMD, and 1st REM min were relatively robust between AUD patients and healthy controls after the outlying study was omitted, thus rendering them as reliable measures. This suggests that they could effectively reflect the true characteristics of sleep disturbance in individuals with AUD.

Although this meta-analysis provides insights into sleep disturbance in AUD patients, there are several limitations. First, the number of studies included was small. This prevented us from examining the interaction effects of multiple moderator variables and exploring extended moderator analysis. Similarly, the small number of studies increased the second-order sampling error and decreased the accuracy in the estimation of the mean effect sizes. Additionally, AUD patients may experience different sleep disturbances during dependence, abstinence, and recovery. The current results may reflect the sleep disturbance of AUD patients with abstinence, thus limiting generalizability to other stages of AUD. Finally, the present study only reviewed the parameters of sleep macroarchitecture commonly reported in PSG studies with AUD patients; however, AUD-related sleep abnormalities are not limited to these variables. Other variables, such as periodic leg movements, delta-band power/integrated amplitude, and quantitatively analyzed heart rate variability, have also been observed.35,65,66 Therefore, it is important for future studies to explore these variables and continue to investigate other aspects of sleep disturbances related to AUD.

ConclusionThe main objective of this meta-analysis was to comprehensively examine the sleep macroarchitecture abnormalities in individuals with AUD and the impact of AUD-related factors and demographic factors on sleep disturbance. The findings of this study indicated that individuals with AUD exhibited impairments in TST, SOL, SE, NREM, REM, and 1st REM min compared to their healthy counterparts. Furthermore, factors such as ethnicity, age, gender, abstinence period, and concurrent substance use were found to moderate the effects of AUD on sleep macroarchitecture. These results suggest that sleep macroarchitecture characteristics could serve as valuable descriptive parameters for addressing sleep-related issues associated with AUD and for profiling the clinical condition of patients. Further exploration of the neurobiology of sleep in individuals with AUD is crucial to fully grasp the implications of these findings, which should be considered within the context of normal developmental changes in sleep patterns.

Ethical considerationsAll analyses were based on previously published studies, therefore no ethical approval or patient consent is required.

This work was supported by grants from Discipline Leader of the Three-Year Action Plan for the Construction of Public Health System in Shanghai (Psychology and Mental Health, GWV-10. 2-XD26) and Shanghai Clinical Research Center for Mental Health (19MC1911100).