Substance use disorder (SUD) has become a major concern in public health globally, and there is an urgent need to develop an integrated psychosocial intervention. The aims of the current study are to test the efficacy of the integrated treatment with neurofeedback and mindfulness-based therapy for SUD and identify the predictors of the efficacy.

MethodsThis study included 110 participants with SUD into the analysis. Outcome of measures includes demographic characteristics, severity of dependence, quality of life, symptoms of depression, and anxiety. Independent t test is used to estimate the change of scores at baseline and three months follow-up. Generalized estimating equations are applied to analyze the effect of predictors on the scores of dependence severity over time by controlling for the effects of demographic characteristics.

ResultsA total of 22 (20 %) participants were comorbid with major mental disorder (MMD). The decrement of the severity in dependence, anxiety, and depression after treatment are identified. Improved scores of qualities of life in generic, psychological, social, and environmental domains are also noticed. After controlling for the effects of demographic characteristics, the predictors of poorer outcome are comorbid with MMD, lower quality of life, and higher level of depression and anxiety.

ConclusionThe present study implicates the efficacy of integrated therapy. Early identification of predictors is beneficial for healthcare workers to improve the treatment efficacy

Substance use has become a major public health concern affecting many people worldwide. According to the World Drug Report 2021,1 around 275 million people used substances globally in 2020 with a prevalence of 0.55 %, which is an increase of 22 % from 2010. In Taiwan, the estimated prevalence of substance use was around 0.6 % in 2020,1 and another epidemiological study reported a 1.29 % lifetime prevalence of ever using an illicit drug,2 demonstrating the unneglected impact of substance use. Substance use killed about half a million people in 2019, and the use of injected substances is commonly associated with blood borne diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C infection.1 These injected substances are often related to opioids, which are also associated with crime, violence, and comorbidity with other mental illnesses.3,4 Although not popular in East Asia, cocaine, as an injected substance, has been associated with suicidality, blood borne diseases, violence, mortality, and decline in productivity.5,6

In addition to injected drugs, other non-injected substances also have harmful effects. Ketamine acts as a psycho-depressant with sedative, dissociative, and anesthetic effects, and it has been reported to induce hallucinations.7 The long-term abuse of ketamine has been shown to result in cognitive dysfunction, schizophrenia-like symptoms, fibrosis of the bladder, and neuron toxicity such as pain and tremors.8 Amphetamine and its derivative, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) are psychostimulants which are also having an increasing impact on society. Chronic amphetamine abuse has been shown to cause delusions, hallucinations, and cognitive impairment.9 MDMA is a well-known “club drug” which is associated with intense excitement and euphoria.10,11 However, chronic abusers of MDMA experience sleep disturbance, impulsivity, and mood disorder.12 Moreover, new psychoactive substances with similar structures to amphetamine have has also become a serious problem.13 These substances can also have neurotoxic effects resulting in mood swings and agitation,14 and they can often be undetected in urine screening due to growing variability.15

Due to the growing and harmful impacts of substance use disorder (SUD), various treatment strategies have been developed. Besides pharmacotherapy, recent evidence has shown that psychosocial interventions such as family-based therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), multicomponent approaches, and mindfulness-based therapy can be effective for SUD.16 Moreover, neurofeedback also demonstrates its efficacy in substance use disorder to alter activities of brain waves, enhance neuropsychological function, reduce craving and anxiety.17,18 On the other hand, factors interfering with the treatment outcomes of SUD have also gained increasing attention. A previous study demonstrated that higher pre-treatment impulsivity could predict worse treatment outcomes in patients with SUD.19 Another study revealed that patients receiving treatment for SUD had higher rates of substance overdose if they had a history of intravenous drug use and mood dysregulation.20 Cognitive impairment has been reported to predict the risk of dropout during treatment for SUD.21

In addition, comorbidity with major mental disorder (MMD) may also interfere the treatment efficacy and prognosis of SUD. Among patients with SUD, those who coexisted with other mental illness demonstrated poor quality of life, impaired sleep pattern, and worse clinical outcomes.22,23 Other studies with longitudinal follow-up also exhibited the undesirable impact of mental comorbidities for treatment outcome of SUD.24,25 In summary, identifying the predictors of treatment efficacy or factors associated with treatment for SUD may help healthcare workers to make appropriate decisions or consider alternative interventions for patients who may have a poor response to treatment.

To effectively treat SUD, it is important to establish a comprehensive treatment program to integrate the multiple domains of intervention, such as case management, clinical treatment, and psychological interventions. However, few studies have assessed the psychosocial predictors of treatment outcomes among patients with SUD. Therefore, in this study, we developed an integrated treatment program to enhance the treatment efficacy of patients with SUD. This program includes psychological interventions, which combines neurofeedback therapy and mindfulness-based relapse prevention group therapy. The aims of the current study were to estimate the efficacy of this integrated program and identify the factors associated with treatment outcomes.

MethodsEthicsBefore initiating the present study, it was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital (KSPH-2019-23) according to the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and national legal requirements (Human Subjects Research Act, Taiwan). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants at the time of recruitment.

Protocols, participants, and proceduresThe current study derived data from the “Establish an integrated medical demonstration center for drug addiction: a pilot program (EIMDCDA)” project, which is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04426565). We collected data from March 2020 to May 2023 in the database of the EIMDCDA project. The EIMDCDA project was initiated in March 2020 with the aim of developing multi-dimensional strategies for the treatment and rehabilitation of patients with SUD, and further provide intervention programs to the community. This ongoing project is conducted by healthcare workers at the psychiatric departments of seven clinical institutes in Kaohsiung, Pingtung, and Penghu, Taiwan, including medical centers, regional hospitals, and district hospitals. The EIMDCDA project consists of three major intervention components, case management, clinical treatment in the outpatient department (OPD), and psychological intervention. The details are as follows:

- 1)

Case management: Initial screening of participants is performed by case managers with a multi-dimensional and patient-centered approach. A SBIRT (screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment)26 service is used for the early identification and interventions for patients with SUD, and it has been reported to be effective in reducing alcohol and illicit substance use.27 After recruiting the participants, the case managers refer them for clinical treatment and psychological interventions, and then follow their condition regularly to ensure adherence to treatment. In addition, the participants are referred to a social welfare department if necessary.

- 2)

Clinical treatment at the OPD: The participants are evaluated at the OPD of a hospital by qualified psychiatrists who are specialized in substance addiction. A diagnostic interview is used initially to confirm the diagnosis of SUD and comorbidities. Clinicians then discuss the treatment course, recent stressors, and feedback of treatment with the participants. A brief psychological intervention is applied if necessary. The participants are treated with pharmacotherapy if they are intoxicated, have substance withdrawal symptoms, or psychiatric comorbidities such as depressive disorder. The case managers assist in regular assessments using questionnaires.

- 3)

Psychological intervention: The participants are referred to a psychological department after the first OPD visit. The integrated therapy consists of 12 sessions of mindfulness-based relapse prevention group therapy28 and 12 sessions of neurofeedback therapy alternatively. The entirely psychological intervention will be completed in 12 weeks. The mindfulness-based relapse prevention group therapy alters the guideline developed by Professor Bowen and colleagues,28,29 and it holds 12 sessions, once per week, and 60 minutes per session. The protocol of neurofeedback therapy in the EIMDCDA project principally followed previous evidences.30-32 The neurofeedback was applied to enhance the beta wave and sensorimotor rhythm, and these trainings could improve attention and cognitive deficiency, which were associated with addiction.30-32 We hold the 12 sessions twice per week, and 50 min per sessions. The details of psychological intervention are shown in Supplementary tables 1 and 2.

Recruitment advertisements are placed on the billboards of local government offices, hospitals, clinics, schools, and public areas in the community. Online advertisements are uploaded to popular social media platforms such as Facebook and Line. People who wish to participate in this project are assessed by case managers and clinicians at an OPD. The inclusion criteria of the EIMDCDA are participants who: (1) are at least 20 years of age; (2) meet the DSM-5 criteria for SUD as assessed by psychiatrists; (3) can understand the objective and process of the project; and (4) sign informed consent before treatment. The exclusion criteria are participants who: (1) are below 20 years of age or above 65 years of age; and (2) cannot cooperate with the investigation tools. The initial screening and interventions include SBIRT, diagnostic interview, physio-biological examination, and psychological clinical assessment as well as self-reported questionnaires. After the initial assessment, the participants receive integrated psychological intervention in 12 weeks. The frequency of visits to the OPD is around once every 2 weeks to once a month depending on the clinical judgement of the psychiatrists. The whole course of treatment is completed within 9 months after the initial assessment. The questionnaires are completed on initiating treatment and then once every 3 months.

Outcome measuresThe severity of dependence scale (SDS)The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) is used as the primary outcome to measure treatment efficacy. The SDS is composed of five self-reported items scored using a 4-point Likert scale to measure the severity of addiction to illicit substances. A higher total SDS score indicates a higher severity of dependence. The Chinese version of the SDS has been verified with good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha: 0.75) and test-retest reliability (0.88).33

The world health organization quality of life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)The Taiwan version of the WHOQOL-BREF is used to estimate the quality of life in various domains.34 This self-administered questionnaire is widely used to measure generic psychometric status with good reliability and validity.34 It is composed of 28 items and five categories. Each item is scored using a 5-point Likert scale. The five categories include two generic items, seven items of physical capacity, six items of psychological well-being, four items of social relationships, and nine items of environmental factors. Higher scores of each category represent better quality of life in that category.

Beck depression inventory (BDI)The Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is one of the most widely used tools to measure the severity of depression in Taiwan. This translated version has been tested with good reliability and validity.35 It is a self-administered questionnaire with 21 items, and each item is scored using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. A higher total BDI score indicates a more severe level of depression.

Beck anxiety inventory (BAI)The Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is used to measure the severity of anxiety. It is also a self-reported questionnaire and is comprised of 21 items. Each item is scored using a 4-point Likert scale. The Chinese version of the BAI has been shown to have good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha: 0.95) and validity.36

Demographic informationDemographic information from the EIMDCDA was collected, including sex (male or female), employment status (employed or unemployed), marital status (married, single, divorced, or widowed), nicotine use (yes or no), alcohol use (yes or no), MMD (with or without), age, and duration of education. The MMD indicated that participants had other mental comorbidities and received pharmacotherapy for the comorbidities.

Statistical analysisAs the EIMDCDA is an ongoing project, data were collected from March 2020 to May 2023. Due to the limited number of cases, only baseline scores and measurements at 3 months of follow-up were used in the analysis. Initially, descriptive statistics were conducted to summarize the clinical characteristics at baseline. The patients were divided into groups with and without MMD, and the two groups were compared. Pearson's χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and the independent t-test was used for continuous variables. The efficacy of treatment was estimated using the independent t-test for comparisons between the scores at baseline and at 3 months of follow-up. These scores included SDS, five category scores of the WHOQOL (generic, physical, psychological, social, and environmental scores), BAI and BDI. To adjust the effect of age, we further applied the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for the difference of scores at baseline and at 3 months follow-up.

To estimate the factors associated with changes in SDS scores over time by controlling for the effects of other factors, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with a first-order autoregressive working correlation structure37 were used. Furthermore, each factor in the analysis was adjusted for demographic characteristics, including sex, age, duration of education, marital status, and employment. All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All data were processed using SPSS version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

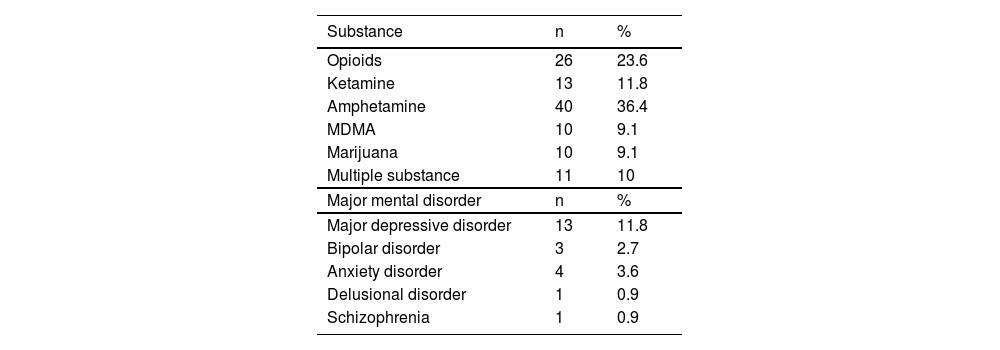

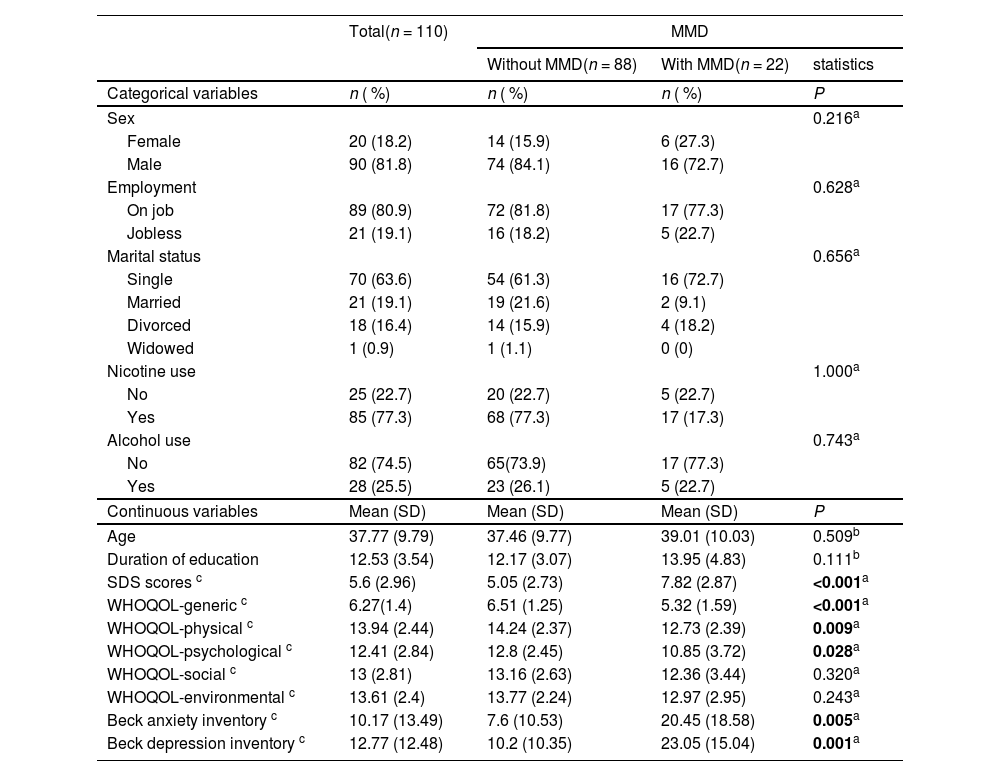

ResultsDuring the inclusion period, a total of 180 individuals were screened. Of these individuals, 48 dropped out from the project (26.67 %) due to loss of contact during the treatment course (n = 17), legal problems (e.g., being arrested, n = 12), and conflict of schedule during treatment (n = 19). Moreover, 22 participants did not complete the first 3 months of follow-up and therefore did not complete questionnaires. The data of the remaining 110 participants were entered into the analysis. Of these 110 participants, 36.4 % (n = 40) had amphetamine use disorder, and 11.8 % (n = 13) were comorbid with major depressive disorder (Table 1). The demographic characteristics and comparisons between the participants with or without MMD are summarized in Table 2. Of the 110 participants, 81.8 % (n = 90) were male, the mean age was 37.77±9.79 years, and 20 % (n = 22) were comorbid with MMD. In the comparison between the MMD and non-MMD groups, the participants with MMD had significantly higher SDS, BAI, and BDI scores than those without MMD. In addition, participants with MMD demonstrated significantly lower scores of generic, psychological, and physical categories of the WHOQOL than those without MMD.

Distribution of substance use disorder and major mental disorder (n = 110).

MDMA: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Demographic characteristics at baseline comparing patients with substance use disorder comorbid with or without major mental disorder.

| Total(n = 110) | MMD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without MMD(n = 88) | With MMD(n = 22) | statistics | ||

| Categorical variables | n ( %) | n ( %) | n ( %) | P |

| Sex | 0.216a | |||

| Female | 20 (18.2) | 14 (15.9) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Male | 90 (81.8) | 74 (84.1) | 16 (72.7) | |

| Employment | 0.628a | |||

| On job | 89 (80.9) | 72 (81.8) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Jobless | 21 (19.1) | 16 (18.2) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Marital status | 0.656a | |||

| Single | 70 (63.6) | 54 (61.3) | 16 (72.7) | |

| Married | 21 (19.1) | 19 (21.6) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Divorced | 18 (16.4) | 14 (15.9) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Widowed | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Nicotine use | 1.000a | |||

| No | 25 (22.7) | 20 (22.7) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Yes | 85 (77.3) | 68 (77.3) | 17 (17.3) | |

| Alcohol use | 0.743a | |||

| No | 82 (74.5) | 65(73.9) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Yes | 28 (25.5) | 23 (26.1) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Continuous variables | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P |

| Age | 37.77 (9.79) | 37.46 (9.77) | 39.01 (10.03) | 0.509b |

| Duration of education | 12.53 (3.54) | 12.17 (3.07) | 13.95 (4.83) | 0.111b |

| SDS scores c | 5.6 (2.96) | 5.05 (2.73) | 7.82 (2.87) | <0.001a |

| WHOQOL-generic c | 6.27(1.4) | 6.51 (1.25) | 5.32 (1.59) | <0.001a |

| WHOQOL-physical c | 13.94 (2.44) | 14.24 (2.37) | 12.73 (2.39) | 0.009a |

| WHOQOL-psychological c | 12.41 (2.84) | 12.8 (2.45) | 10.85 (3.72) | 0.028a |

| WHOQOL-social c | 13 (2.81) | 13.16 (2.63) | 12.36 (3.44) | 0.320a |

| WHOQOL-environmental c | 13.61 (2.4) | 13.77 (2.24) | 12.97 (2.95) | 0.243a |

| Beck anxiety inventory c | 10.17 (13.49) | 7.6 (10.53) | 20.45 (18.58) | 0.005a |

| Beck depression inventory c | 12.77 (12.48) | 10.2 (10.35) | 23.05 (15.04) | 0.001a |

MMD: major mental disorder; SD: standard deviation; SDS: the severity of dependence scale.

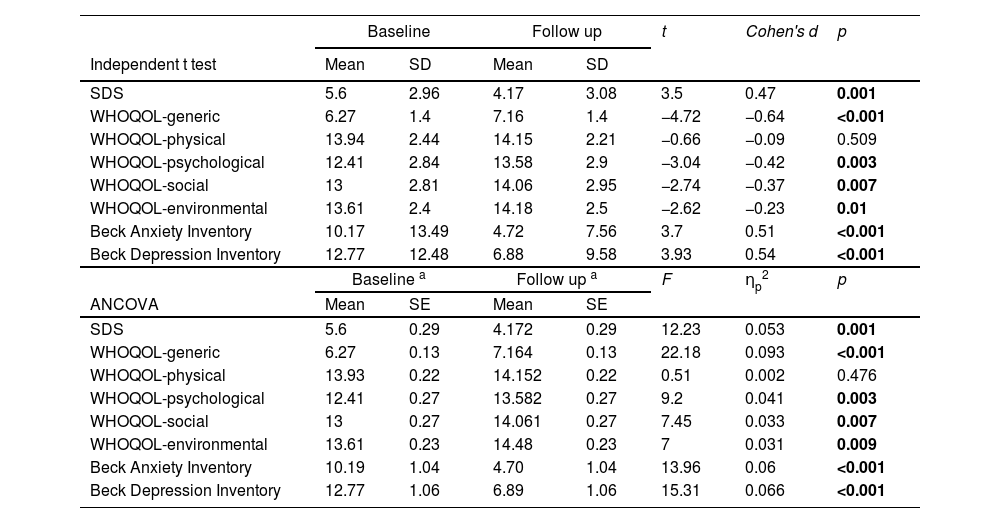

Table 3 demonstrates the treatment efficacy according to comparisons of scores at baseline and follow-up at 3 months. The SDS, BAI and BDI scores were significantly lower at 3 months than those at baseline (baseline vs. follow-up: 5.6±2.96 vs. 4.17±3.08; 10.17±13.49 vs. 4.72±7.56; and 12.77±12.48 vs. 6.88±9.58, respectively). This indicated decreases in the severity of dependence, anxiety, and depression after treatment. In addition, significant increases in the generic, psychological, social, and environmental domain scores of the WHOQOL at 3 months demonstrated improvements in the quality of life in these domains (baseline vs. follow up: 6.27±1.4 vs. 7.16±1.4; 12.41±2.84 vs. 13.58±2.9; 13±2.81 vs. 14.06±2.95; 13.61±2.4 vs. 14.18±2.5). On the other hand, the result of ANCOVA demonstrated the same pattern as independent t-test. The SDS, BAI, and BDI scores were significantly decreased at 3 months. The generic, psychological, social, and environmental domain scores of the WHOQOL significantly increased at 3 months.

Efficacy of treatment derived from the difference of scores between baseline and follow up.

| Baseline | Follow up | t | Cohen's d | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent t test | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| SDS | 5.6 | 2.96 | 4.17 | 3.08 | 3.5 | 0.47 | 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-generic | 6.27 | 1.4 | 7.16 | 1.4 | −4.72 | −0.64 | <0.001 |

| WHOQOL-physical | 13.94 | 2.44 | 14.15 | 2.21 | −0.66 | −0.09 | 0.509 |

| WHOQOL-psychological | 12.41 | 2.84 | 13.58 | 2.9 | −3.04 | −0.42 | 0.003 |

| WHOQOL-social | 13 | 2.81 | 14.06 | 2.95 | −2.74 | −0.37 | 0.007 |

| WHOQOL-environmental | 13.61 | 2.4 | 14.18 | 2.5 | −2.62 | −0.23 | 0.01 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 10.17 | 13.49 | 4.72 | 7.56 | 3.7 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 12.77 | 12.48 | 6.88 | 9.58 | 3.93 | 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Baseline a | Follow up a | F | ηp2 | p | |||

| ANCOVA | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

| SDS | 5.6 | 0.29 | 4.172 | 0.29 | 12.23 | 0.053 | 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-generic | 6.27 | 0.13 | 7.164 | 0.13 | 22.18 | 0.093 | <0.001 |

| WHOQOL-physical | 13.93 | 0.22 | 14.152 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.002 | 0.476 |

| WHOQOL-psychological | 12.41 | 0.27 | 13.582 | 0.27 | 9.2 | 0.041 | 0.003 |

| WHOQOL-social | 13 | 0.27 | 14.061 | 0.27 | 7.45 | 0.033 | 0.007 |

| WHOQOL-environmental | 13.61 | 0.23 | 14.48 | 0.23 | 7 | 0.031 | 0.009 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 10.19 | 1.04 | 4.70 | 1.04 | 13.96 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 12.77 | 1.06 | 6.89 | 1.06 | 15.31 | 0.066 | <0.001 |

SDS: the severity of dependence scale; WHOQOL: world health organization quality of life-BREF; ANCOVA: analysis of covariance.

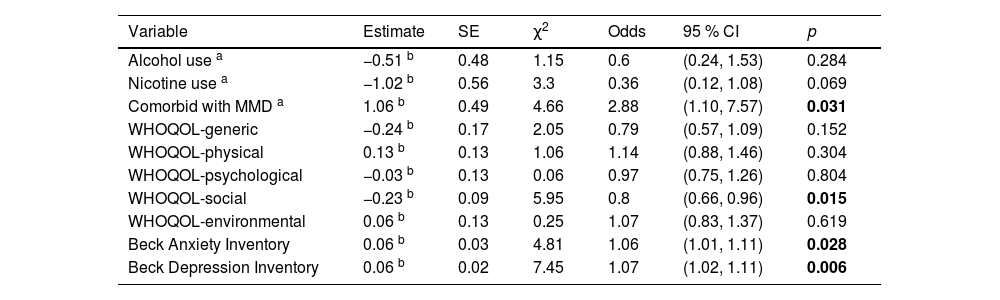

Finally, Table 4 shows the results of GEEs examining the factors associated with changes in SDS scores over time. After controlling for the effects of the demographic factors, being comorbid with MMD remained statistically significant (estimate: 1.06, 95 % CI: 1.1–7.57, P = 0.031), meaning that the participants who were comorbid with MMD had a higher SDS score (1.06 points) than those without MMD. This indicated that the participants who were comorbid with MMD had worse treatment outcomes with regards to the severity of substance dependence. With regards to the WHOQOL scores, the social (estimate: −0.23, 95 % CI: 0.66-0.96, P = 0.015) domains reached statistical significance. For every 1-point increase in social scores, there was a reduction in SDS score of 0.23 points. This showed that a higher level of quality of life in social domain was associated with a lower severity of dependence. In addition, higher BAI (estimate: 0.06, 95 % CI: 1.01–1.11, P = 0.028) and BDI (estimate: 0.06, 95 % CI: 1.02-1.11, P = 0.006) scores were significantly associated with higher SDS scores, demonstrating worse treatment outcomes in those with more severe symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Predictors over time on the total scores of SDS using generalized estimating equations.

| Variable | Estimate | SE | χ2 | Odds | 95 % CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use a | −0.51 b | 0.48 | 1.15 | 0.6 | (0.24, 1.53) | 0.284 |

| Nicotine use a | −1.02 b | 0.56 | 3.3 | 0.36 | (0.12, 1.08) | 0.069 |

| Comorbid with MMD a | 1.06 b | 0.49 | 4.66 | 2.88 | (1.10, 7.57) | 0.031 |

| WHOQOL-generic | −0.24 b | 0.17 | 2.05 | 0.79 | (0.57, 1.09) | 0.152 |

| WHOQOL-physical | 0.13 b | 0.13 | 1.06 | 1.14 | (0.88, 1.46) | 0.304 |

| WHOQOL-psychological | −0.03 b | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.97 | (0.75, 1.26) | 0.804 |

| WHOQOL-social | −0.23 b | 0.09 | 5.95 | 0.8 | (0.66, 0.96) | 0.015 |

| WHOQOL-environmental | 0.06 b | 0.13 | 0.25 | 1.07 | (0.83, 1.37) | 0.619 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 0.06 b | 0.03 | 4.81 | 1.06 | (1.01, 1.11) | 0.028 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 0.06 b | 0.02 | 7.45 | 1.07 | (1.02, 1.11) | 0.006 |

SDS: the severity of dependence scale; MMD: major mental disorder; SE: standard error; χ2: Wald chi-square; Odds: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Most of the participants in this study had amphetamine use disorder, and the majority of the patients comorbid with MMD had mood disorder. Our results showed the good efficacy of treatment for patients with SUD in the EIMDCDA project. The significant decreases in SDS, BAI and BDI scores demonstrated the efficacy of treatment with regards to substance dependence, anxiety, and depression. Moreover, the significant increment of generic, psychological, social, and environmental domains of WHOQOL indicated the improvement of quality of life after treatment. We also identified the unique role of comorbidity with MMD in attenuating treatment efficacy. Compared to the patients without MMD, those with MMD had higher baseline SDS, BAI and BDI scores, demonstrating worse substance dependence, anxiety and depression. In addition, the significantly lower scores of the generic, physical, and psychological domains of the WHOQOL revealed the worse quality of life in the patients comorbid with MMD. On the other hand, comorbidity with MMD, higher level of depression, higher level of anxiety, and lower quality of life predicted worse treatment efficacy for substance dependence. The quality-of-life domain included social domain, and similar but insignificant trends were also found in the generic and psychological domains of the WHOQOL. Several clinical implications of the current study are addressed. First, we developed a combination therapy with mindfulness-based relapse prevention group therapy and neurofeedback therapy in relatively fewer courses than conventional neurofeedback therapy. Previous evidences suggested that most of the training courses for mental illness took thirty to fifty courses,38,39 which may be a burden for patients and healthcare workers. We simplify the courses of neurofeedback to 12 times and add additional 12 courses of mindfulness-based therapy, which demonstrates good efficacy and saves time for patients and healthcare workers. Second, we reported the treatment efficacy in reducing severity of substance dependence, depression, and anxiety, which were comparable to other study with conventional neurofeedback.39 Third, the combination therapy with neurofeedback and mindfulness-based therapy is novel and rarely reported. Few clinical trials focus on the combination therapy, and it is common with cognitive behavior therapy and motivation interview.40 Therefore, it deserves further studies with this combination therapy to explore the detailed efficacy for SUD, and it may provide valuable data for the head-to-head comparison with other psychological intervention in the meta-analytic study.

At follow-up after 3 months, improvements in the symptoms of dependence and depression were noted. A previous integrated intervention study consisting of CBT and mindfulness-based relapse prevention therapy among patients with bipolar disorder and SUD also demonstrated decreases in depressive symptoms and substance use.41 Another study also reported the efficacy of the neurofeedback therapy on reducing somatic symptoms, depression, and craving for patients with opioid use disorder.39 Our findings are consistent with those of these previous studies, indicating the efficacy of treatment in both severity of dependence and mood symptoms including depression and anxiety. In addition, a higher severity of depression and anxiety was associated with a higher severity of dependence over time, indicating worse efficacy of treatment. A previous study of an integrated intervention for patients with alcohol use disorder reported that a higher level of depression was associated with an increased use of the intervention program.42 This may imply an association between depression and dependence. Moreover, another study of patients comorbid with SUD and other mental disorders showed a significant association between a higher level of depression and anxiety with a lower odds of substance abstinence.43

In the current study, comorbidity with MMD was associated with worse baseline scores and could predict worse treatment outcomes. As most of the individuals with MMD had mood disorder in this study, it is rational that they have higher levels of depression and anxiety, leading to more severe substance dependence. Moreover, comorbidity of MMD was not only associated with more severe substance dependence at baseline, but it also predicted a worse outcome with regards to dependence severity after treatment. Although few studies have investigated the association between severity of dependence and comorbidity with MMD, relationships between SUD and other psychiatric comorbidities have been investigated. A 10-year follow-up study reported the significant prospective predictors of mental disorders for the onset of SUD over time.44 Another study indicated that individuals with mental disorders are at a higher risk of transitioning from the first use of a substance to dependence.45 Similarly, a previous study of group intervention therapy for SUD reported that patients with severe mental illnesses had higher dropout rates from treatment courses than those without severe mental illnesses, and subsequently worse treatment outcomes.46 Worse clinical outcomes have also been reported for patients comorbid with SUD and other mental illnesses compared to those with SUD without comorbidities.47 Regarding the etiology between comorbidity with MMD and poor clinical outcome, it may result from several factors. First, precious literatures report the association between MMD and impaired treatment adherence.48,49 Second, lack of insight among patients with MMD is common and results in poor prognosis.50 In summary, the current study further extends the applicability of these previous studies, and demonstrates that comorbidity with MMD can predict more severe dependence, leading to worse treatment outcomes for SUD.

In addition to the severity of mood symptoms and comorbidities, the present study showed the effect of quality of life on treatment efficacy. A prospective study of in-patient treatment for SUD reported efficacy on improving the quality of life,51 which is consistent with the findings of the current study. Another study also reported improvements in health-related quality of life after treatment for SUD.52 A previous study investigating the association between severity of dependence and quality of life in subjects with benzodiazepine dependence reported that a lower quality of life was associated with higher benzodiazepine intake,53 implying the higher severity of dependence. Furthermore, a higher severity of dependence has been associated with lower health-related quality of life among patients with SUD receiving treatment.54 The current study further confirms the role of quality of life in the severity of dependence. Moreover, we identified that social domain of the WHOQOL can significantly affect the severity of substance dependence, and generic as well as psychological domain of the WHOQOL show similar pattern.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the limited numbers of participants may have compromised the interpretation and applicability of the results. Difficulty during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and relatively frequent OPD visits as well as psychological interventions in the first 3 months may have contributed to the dropout rate. Second, as an interventional study with no placebo group, it cannot be considered to be a formal clinical trial. However, the present study may have included patients more representative of real-world clinical practice. Third, as the common comorbidity with SUD and other mental illness,55 the mental comorbidity in our study is relatively low (20 %). It may result from the selection bias of the inclusion criteria, where participants should fully understand the goals and the whole process of treatment course. Therefore, some participants may not be recruited due to predominantly cognitive impairment due to their mental comorbidities. Fourth, some of important variables are not measured in this study. For instance, the coping strategies for patients with SUD are associated with treatment adherence.56 Moreover, the clinical severity of mental comorbidities is unidentified. Fifth, the combination therapy requires psychologists or related specialists for mindfulness group therapy and neurofeedback, which may limit the applicability. Finally, psychopharmacotherapy for mental comorbidities, substance intoxication or withdraw may interfere the efficacy of combination therapy.

ConclusionsThe findings of the current study demonstrated the efficacy of treatment and its predictors among patients with SUD. The results imply the importance of integrated therapy for patients with SUD, including case management and combination of neurofeedback as well as mindfulness-based therapy. Healthcare workers should pay attention to patients with higher levels of mood symptoms, worse quality of life, and comorbidity with MMD, as these factors may compromise treatment efficacy. However, how to maintain a balance between the intensity or frequency of treatment and dropout remains a challenge. Moreover, the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic shows the urgent need to establish alternative interventions for patients with SUD, such as teletherapy or changing the frequency of visits. Finally, several efforts may be beneficial to extend the applicability of the current study. First, combination therapy with longer follow-up may help us to identify other dimension of treatment efficacy, such as relapse or abstinence period. Second, a well-controlled study can improve the evidence level of combination therapy, such as non-treatment group or group of treatment as usual.

Role of the funding sourceThis work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (1101761097).

Patient consent statementAll of the participants have signed the informed consent prior to the initiation of the study.

Ethical publication statementThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital (KSPH-2019-23). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

All authors are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The authors thank to the assistances from paramedical staffs at Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital.