The efficacy of antipsychotic drugs in improving negative symptoms of schizophrenia remains controversial. Psychological interventions, such as Social Skills Training (SST) and Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT), have been developed and applied in clinical practice. The current meta-analysis was therefore conducted to evaluate the efficacy of controlled clinical trials using SST and SCIT on treating negative symptoms.

MethodsSystematical searches were carried out on PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO databases. The standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated to assess the effect size of SST/SCIT on negative symptoms. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were conducted to explore sources of heterogeneity and identify potential factors that may influence their efficacy.

ResultsA total of 23 studies including 1441 individuals with schizophrenia were included. The SST group included 8 studies with 635 individuals, and the SCIT group included 15 studies with 806 individuals. The effect size for the efficacy of SST on negative symptoms was -0.44 (95% CI: -0.60 to -0.28; p < 0.01), while SCIT was -0.16 (95% CI: -0.30 to -0.02; p < 0.01).

ConclusionsOur findings suggest that while both SST and SCIT can alleviate negative symptoms, the former appears to be more effective. Our results provide evidence-based guidance for the application of these interventions in both hospitalized and community individuals and can help inform the treatment and intervention of individuals with schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a group of major mental spectrum disorders of unknown etiology, the main clinical symptoms include positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive dysfunction.1-3 Whereas positive symptoms include hallucination, delusion, and disorganized speech. Cognitive dysfunctions include deficits in attention, working memory, and executive function. Negative symptoms have been defined as reductions in motivation, emotion,and/or expressive behavior, are considered to have a prevalence of 15% in first-episode schizophrenia and 25%–30% in cases of chronic schizophrenia, which are even stronger predictors of poor functional outcomes in diagnosed schizophrenics.4,5 Specifically, social dysfunction is predictive of both course and prognosis of schizophrenia.6 Although pharmacological agents are schizophrenia's first-line treatment, they have minimal impact on negative symptoms and cognitive impairments.7,8

Psychosocial treatments, as an adjunct treatment to medications, are now a widely accepted treatment approach, but the overall evidence regarding the efficacy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia is limited. The literature review shows that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) might have the potential to ameliorate negative symptoms of schizophrenia individuals. However, so far there are no methodologically sound clinical trials on CBT, which address negative symptoms as a primary outcome.9-11 The effects of family interventions or psychoeducation on negative symptoms are unsatisfying.12 Although supported employment is superior to other modes of vocational rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness, there are few studies on the impact of negative symptoms.13 Social Skills Training (SST) for schizophrenia was developed to help people with schizophrenia with difficulties in interpersonal situations and relationships, some studies suggest that SST can be effective for improving negative symptoms in the short-term.14,15 Studies have shown that adjunct music therapy improved negative symptoms, but the quality of evidence is still low, more well-designed studies with larger sample size and high quality are needed to confirm the efficiency of adjunct music therapy in treating schizophrenia.16 Empirical studies that have investigated the efficacy of psychosocial treatments (such as SST or SCIT) on negative symptoms are accumulating fast.9,17,18 However, to our knowledge, few of the recent reviews used a meta-analysis design.

Schizophrenia patients individuals with more pronounced negative symptoms have been found to exhibit significantly poorer levels of social skills in conversational and role-play measures.19 Social skills training (SST) is a form of therapy that focuses on improving verbal and nonverbal communication, perception, and responses to social cues. Thereby, SST enhances patients participants’ social functioning, and their ability to cope with navigate social situations.20 Several studies have examined the effects of SST on negative symptoms. Some randomized controlled trials found no significant treatment effect for negative symptoms after SST interventions.21-24 A review identified 11 controlled trials of SST, within which 5 studies indicated that SST was associated with a reduction in negative symptoms at posttreatment.9 A meta-analysis targeting the effect of SST on patients with schizophrenia found the effect of SST on negative symptoms to be inconsistent. Another meta-analysis of 22 clinical trials reported moderate mean effect sizes for negative symptoms.25 Turner et al. (2014) reported similar small-to-medium effect sizes in favor of SST for negative symptoms, and found SST to be superior to other interventions.26 In their most recent meta-analysis of 27 clinical trials, Turner et al. (2018) reported significant medium effects on negative symptoms for SST [20]. Despite the above studies in clinical schizophrenic samples recommending SST for treating negative symptoms,15,25,26 another research suggests that they did not identify any study that tested SST in the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, thereby positing that there is little evidence to support this recommendation.27

Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) is yet another newly developed psychosocial intervention aimed to address the core social cognitive deficits found in schizophrenia.28 SCIT includes cognitive-behavioral therapy and social skills training and is delivered in a group setting.29 The efficacy of SCIT in improving social cognition and other functions in people with schizophrenia has been investigated in previous studies using controlled trials.30,31 Evidence on the efficacy of SCIT for negative symptoms, however, is relatively scarce. Two studies found no significant effects of social cognitive training programs on the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia or on social functioning.32,33 Another meta-analysis showed that patients who received SCIT had lower negative symptom scores.34 Further research is needed to clarify its potential benefits for negative symptoms.

The present meta-analysis advances prior studies on psychosocial rehabilitation for schizophrenia by juxtaposing the efficacy of SST and SCIT in mitigating negative symptoms. We have two primary objectives: First, both SST and SCIT aim to bolster individual adaptation to social contexts, enhance social functioning, and elevate the quality of life. In our investigation, we will amalgamate the effect sizes of both SST and SCIT for a comprehensive analysis, while also executing distinct meta-analyses for each. Second, we aim to validate our hypothesis that SCIT, by fusing cognitive remediation with social skills and problem-solving training, would result in more pronounced alleviation of negative symptoms compared to SST.

MethodsLiterature search strategyWithout publication year limits, the following keywords were entered for identifying relevant published studies: ‘social cognitive interaction training’ OR ‘SCIT’ OR ‘social skills training’ OR ‘SST’ AND ‘schizophrenia’ on PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. We also screened the potentially eligible articles for previous meta-analyses and unpublished articles. Three authors with expertise in psychiatry independently conducted eligibility assessments during three rounds, each involved evaluating titles, abstracts, and full texts. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus was reached under the supervision of the remaining authors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were studies in which: (1) all individuals participating in the study were diagnosed with schizophrenia; (2) the intervention group received SST or SCIT in addition to conventional drug therapy, while the control group received routine medication and care; (3) validated scales such as PANSS, SANS, CAINS, or BNSS were used to measure negative symptoms as disease outcome; (4) the study design was either randomized controlled or cohort studies. All studies were published in English.

Excluded were studies in which: (1) participants were with comorbid diagnoses, such as substance abuse or ultrahigh risk of psychosis; (2) data was missing and could not be obtained by contacting the authors; (3) interventions methods were mixed (such as SST/SCIT plus oxytocin); (4) included overlapping samples. Articles that were case reports, editorials, comments, or review papers were excluded. Reference lists of literature reviews and relevant papers were screened for additional potential papers.

Literature quality assessment for included studiesThe quality of each study was evaluated using the modified Jadad scale,35 which consists of seven items grouped into categories: randomization, blinding strategy, withdrawals/dropouts, inclusion/exclusion criteria, adverse effects, and statistical analysis. Two authors independently assessed the quality of each included study, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus. All studies included in this meta-analysis had Jadad scores of 3 or higher.

Data extractionThe data extracted for the meta-analysis were as follows: patient participant characteristics (mean age, gender ratio, sample size, diagnosis, and initial positive symptom score), intervention details (type, form, frequency, duration), control interventions (type, frequency, active/waitlist control), first author's name, year of publication, and outcome data of included patients. If data were not provided in the study, it was marked as "NR" (not reported). If multiple studies contained overlapping data from the same population, the one with the largest sample size was used in the analysis. Two authors independently extracted the data, and any inconsistencies were discussed with the third author before reaching a consensus.

Effect measuresTo assess the effectiveness of SST/SCIT, we calculated the standard mean difference (SMD) for each study and the pooled SMD. An SMD between 0.2 and 0.5 was considered indicative of mild-to-moderate efficacy, while an SMD between 0.5 and 0.8 indicated moderate-to-large efficacy, in accordance with Cohen's criteria.36 To assess the heterogeneity in effect sizes, I2 was applied which determine the proportion of variability due to true differences between studies rather than chance. A fixed-effect meta-analysis assumes a common effect size across all studies, whereas a random-effects meta-analysis estimates the mean of a distribution of effects. The choice of computational model for meta-analysis should be based on the expected similarity of effect sizes across studies and analytical goals.37

Statistical analysisTo determine statistical significance, we used a significance level of p < 0.05 and conducted all analyses using R (version 3.5.3) with the “meta” or “metafor” packages.38 Our meta-analysis consisted of five steps. First, we assessed the quality of the included studies using the Jadad scale, with studies scoring less than 3 on the scale being excluded. Second, we assessed publication bias using Egger's test and presented a funnel plot for visual inspection. Third, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to identify studies that contributed to high heterogeneity, excluding any study that caused a change in heterogeneity greater than 5%. Fourth, we calculated the pooled effect size based on the SMD. Finally, we conducted subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis to explore sources of heterogeneity in the effect sizes of SST/SCITs for negative symptoms and to identify potential factors influencing their efficacy. This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,39 including careful definition of selection criteria and data analyses of interest.

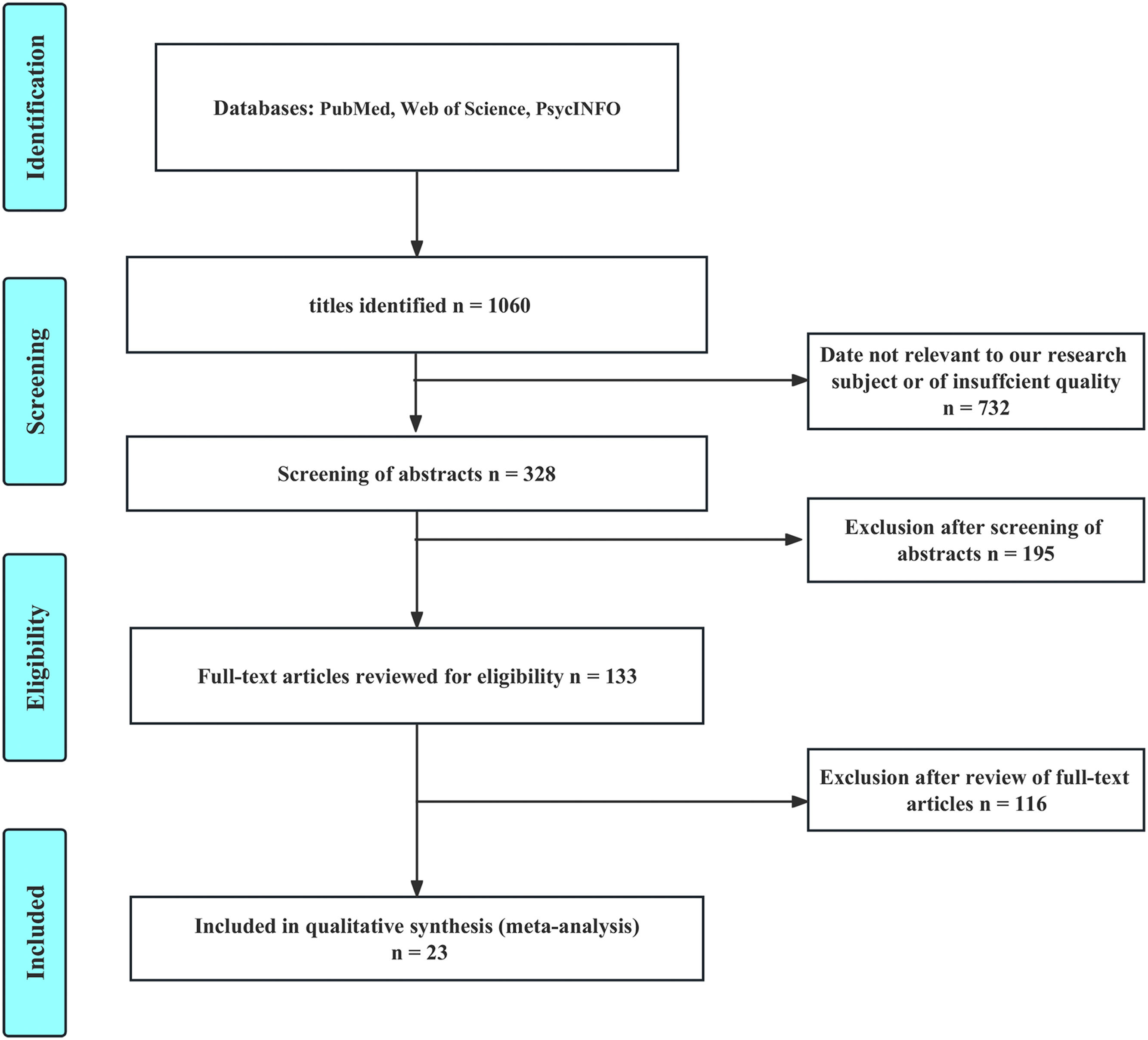

ResultsStudy selectionWe initially identified a total of 1060 potential articles by screening their titles, of which 328 articles were selected for abstract screening. Following this, two investigators conducted a thorough review of the selected articles to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the study. Ultimately, a total of 23 articles, with 1441 participants, met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. A detailed flowchart illustrating the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

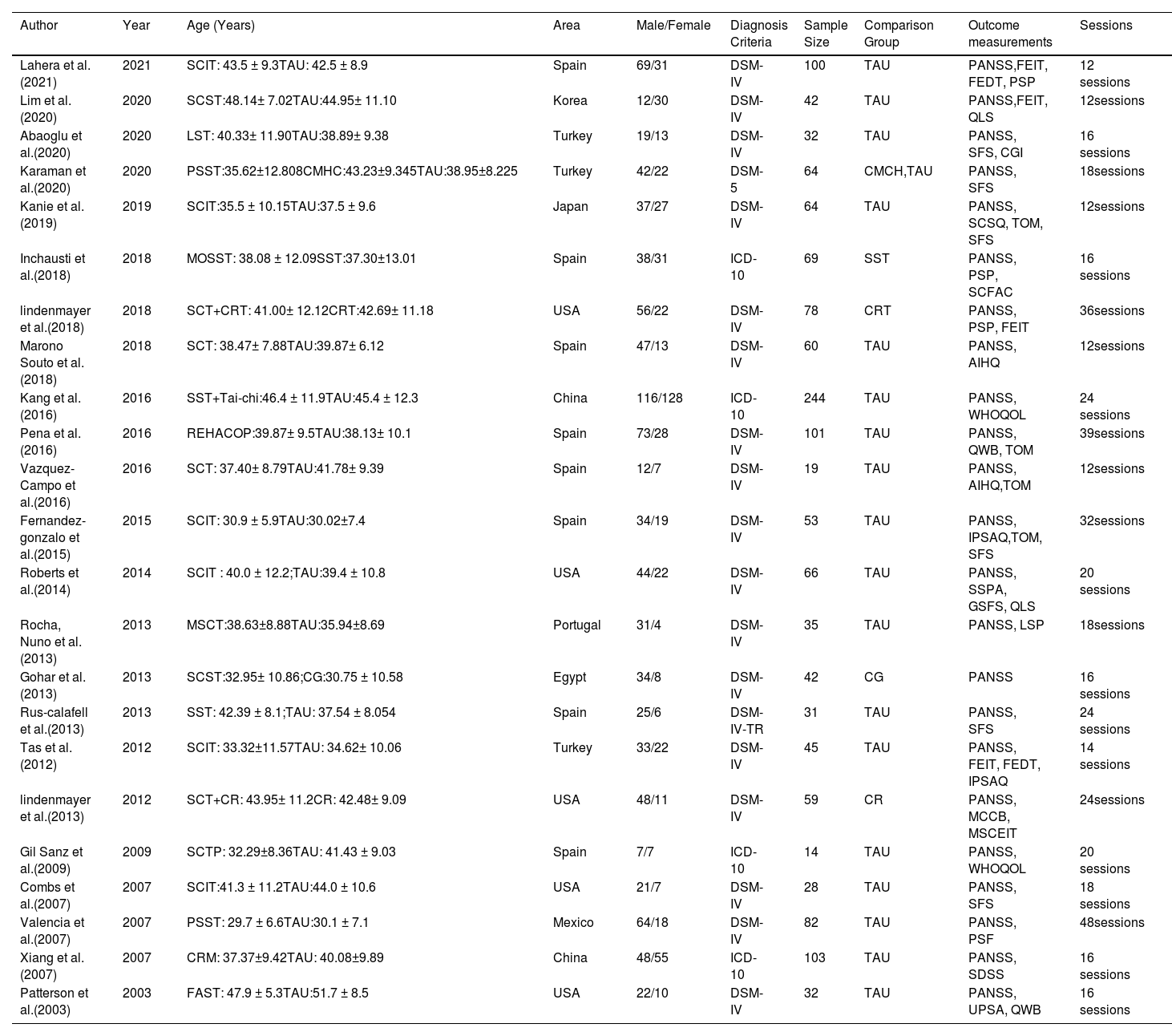

Characteristics of the included studiesTable 1 presents a summary of the 23 studies that were included in the meta-analysis. These studies were conducted in various regions across the world, including Asia (4 studies), Europe (12 study), Africa (1 study), and North America (6 studies). The studies evaluated a range of interventions, including Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT), Social Cognition Skills Training (SCST), Metacognitive and Social Cognitive Training (MSCT), Social Cognitive Training Programme (SCTP), Social Cognition Training (SCT), Social Cognition Training with Cognitive Remediation, Social Skills Training (SST), Psychosocial Skills Training (PSST), the Community Chinese version of the Community Re-Entry Module (CRM), the Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST), and Life Skills Training (LST). The number of studies assessing each intervention varied, with SCIT being the most frequently evaluated intervention (15 studies), followed by SST (8 studies). Table 1 provides more detailed information about the included studies and their characteristics.

The included studies.

Note:SCST,Social cognitive skills training; TAU,Treatment as usual; PANSS, The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale;FEIT,The Face Emotion Identification Task;FEDT,The Face Emotion Discrimination Task; PSP,The Personal and Social Performance Scale; QLS,Quality of Life Scale; LST,Life Skills Training); SFS, Social Functionality Scale; CGI,The Clinical Global Impression Scale; CMHC, The community mental health center;SCSQ, Social Cognition Screening Questionnaire; MOSST,Metacognition-oriented social skills training; SCFAC, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; CMHC,The community mental health center;CRT,Cognitive remediation therapy);AIHQ,Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire;WHOQOL,The World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale-Brief version; REHACOP, An integrative cognitive remediation program; QWB,The Quality of Well-Being; IPSAQ,The Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire; SSPA, Social Skill Performance Assessment;GSFS,The Global Social Functioning Scale; QLS,The Quality of Life Scale-Social; LSP,The life skills profile; CG, Control skills training program; FEDT,The Face Emotion Discrimination Task; CR, Cognitive Remediation; MCCB,The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery; MSCEIT,The Managing Emotions subtest of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; SCTP, Social Cognitive Training Programme; PSF, Psychosocial functioning; CRM, A module of a standardised, structured socialskills trainingprogramme devised at the Universityof California,Los Angeles; SDSS,The Social Disability Screening Schedule; FAST,The Functional Assessment Short Test.

Studies were assessed for their quality using the Jadad scale, and all studies included in the analyses scored higher than 3. Please refer to Table S1 (in Supplemental Materials) for the Jadad scale items of each included study. Publication bias was assessed by illustrating a funnel plot and by Egger's test. The results showed no evidence of publication bias (p = 0.20) (Fig. S1 in Supplemental Materials).

Sensitivity analysisTo identify studies contributing to high heterogeneity, we conducted a sensitivity analysis for the included studies, no study has a greater change than 5% effect on I2 and no study was subsequently excluded (Fig. S2 in Supplemental Materials).

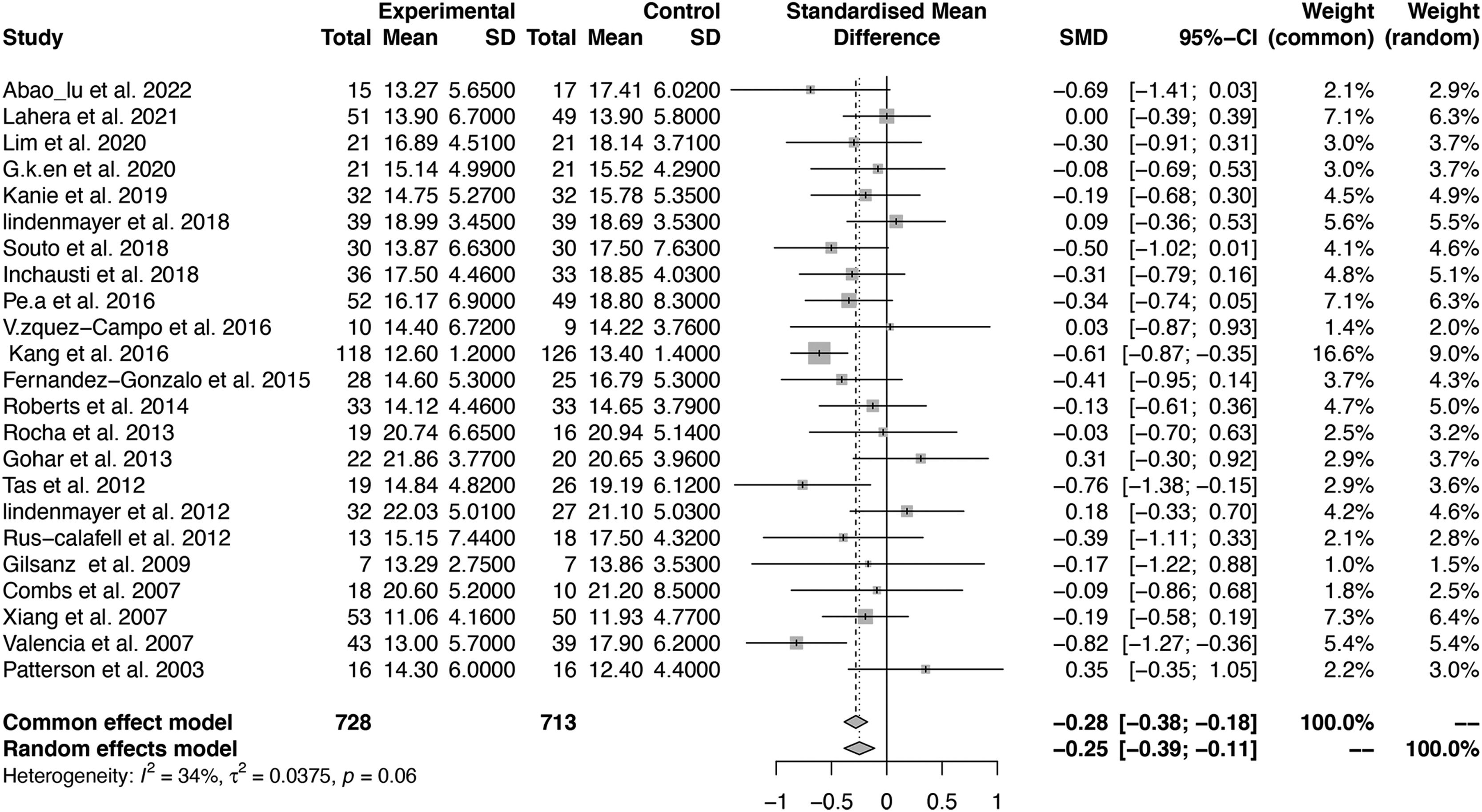

Effect size of SST and SCIT for negative symptomsWe calculated the effect sizes of SST and SCIT interventions (both included SST and SCIT) for the reduction of negative symptoms using the standardized mean difference (SMD). Out of the 23 included studies, all compared SST and SCIT interventions with treatment as usual (TAU) in terms of negative symptom scores in patients individuals with schizophrenia. The estimated effect size was statistically significant (SMD = −0.28, 95% CI [−0.38; −0.18], p < 0.001), with moderate heterogeneity observed among the studies (I2 = 33.9%). The forest plots displaying the pooled effect sizes are presented in Fig. 2.

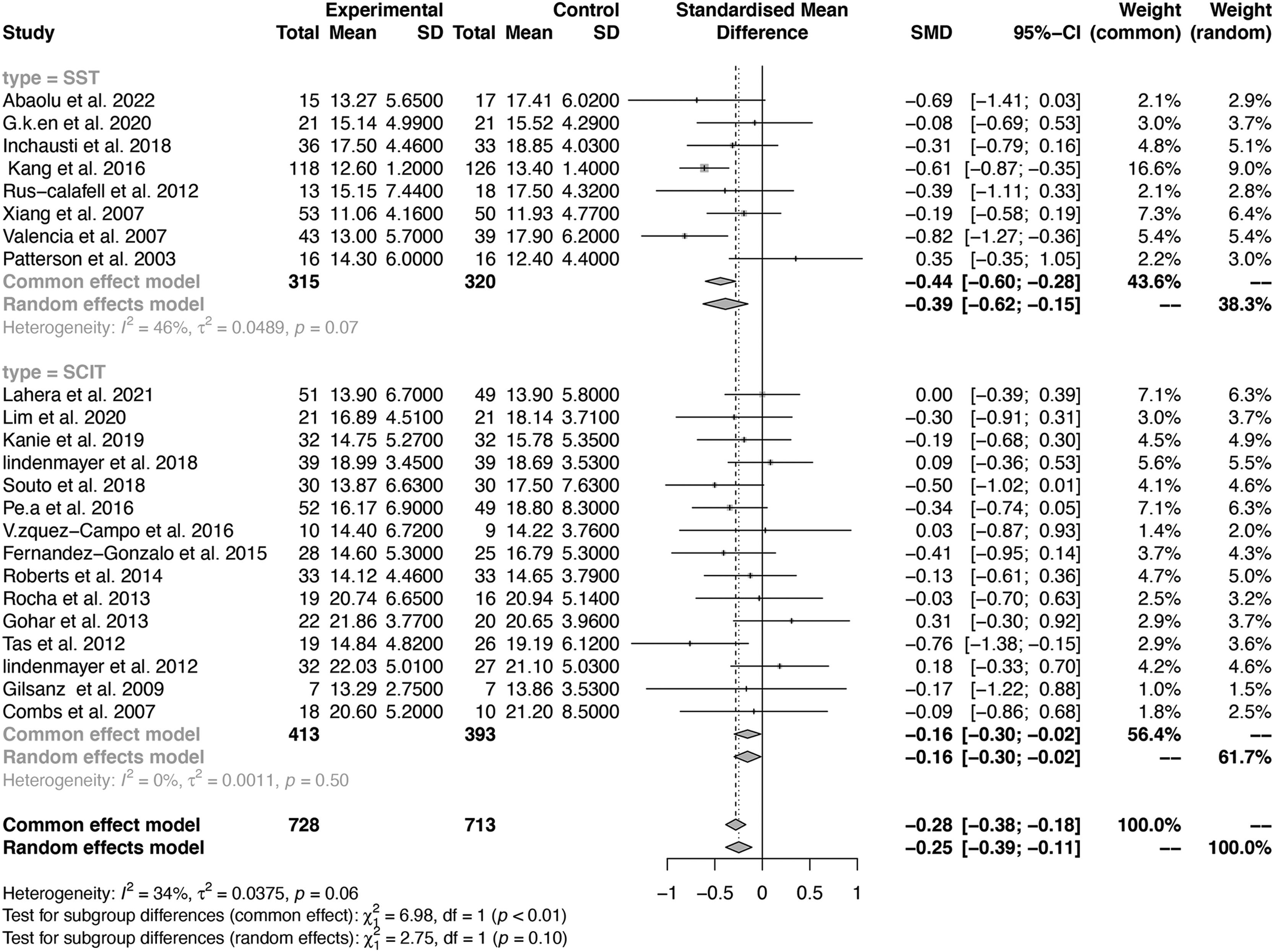

Subgroup analysisSubgroup analysis were caried out to compare the efficacy of SST and SCIT in treating negative symptoms. The effect sizes of SST and SCIT were indicated by the SMD. The pooled SMD and 95% confidence interval (CI) for SST was −0.44 (95% CI: −0.60 to −0.28), while the pooled SMD and 95% CI for SCIT was −0.16 (95% CI: −0.30 to −0.02). The results indicated that SST was more effective in improving negative symptoms compared to SCIT (p = 0.008). Forest plots of pooled effects are shown in Fig. 3.

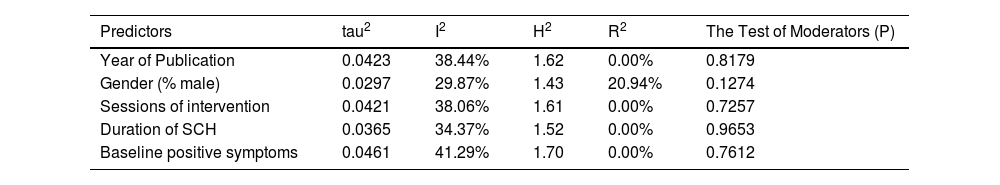

Meta-regression analysisWe conducted a meta-regression analysis to examine the potential influences of the following continuous variables: year of publication, gender ratio (male percentage), mean age, sessions of intervention, duration of illness, and baseline positive symptoms, on the effect size of the interventions for negative symptoms. Results showed that none of the above variables had a significant influence on the effect sizes of the interventions for negative symptoms (p > 0.05). Detailed meta-regression results are summarized in Table 2.

The meta-regression analysis for the efficacy of SST and SCIT to negative symptoms in schizophrenia.

Note: tau2: The estimated amount of residual heterogeneity; I2: The residual heterogeneity; H2: The unaccounted variability; R2: The amount of heterogeneity accounted for.

The current meta-analysis encompassing 1441 patients participants, with schizophrenia found notable effectiveness of both SST and SCIT on treating negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Specifically, SST had a moderate to large effect on negative symptoms, while the effect size of SCIT was relatively lower. Subgroup analyses demonstrated significant differences in the efficacy of the two interventions on negative symptoms, suggesting that SST may be more effective than SCIT in treating negative symptoms.

The study found that SST had a moderate to large effect on reducing negative symptoms. It might be speculated that SST's effectiveness in improving negative symptoms lies in its inherent procedure. First, the group format of the SST intervention allows for ample rehearsal opportunities for all participants. By using behavioral therapy techniques such as role play, participants acquire and practice the required skills, then either positive or corrective feedback is given accordingly. Through behavioral practice, participants observe and repeat the skills until they can successfully use them in real-life situations. Homework assignments are then given to motivate participants to implement these communication skills in their everyday lives.9,20 This training establishes a belief in interpersonal communication and improves patients participants ' social adjustment, capacity to live independently, and daily learning skills, thereby promoting interpersonal interaction, and reducing social withdrawal.

Second, conversation and expressive skill training are the primary content of SST.40 This training improves patients participants' conversational expression skills, increases their interest in social contact, and improves their expression through verbal and non-verbal means (e.g., eye contact, facial expression, language fluency, gestures, and posture). Since negative symptoms of schizophrenia involve both motivational and expressive deficits, through improving patients participants ' expression ability, social skills training may help to reduce speech poverty.

Third, negative symptoms can serve as significant predictors of schizophrenic patients participants’ social functioning outcome.5 Passive-apathy, social withdrawal and active social avoidance are crucial determinants of social functioning. Most existing studies have found that SST improved social functioning of schizophrenia patients individuals,14,15 which in turn may promote the alleviating of negative symptoms. In fact, SST may also help to reduce social discomfort and negativity in social interactions, thereby improving indirect negative symptoms. Overall, SST has been identified as a core technology for social skill intervention and is thought to be essential for improving social function. Furthermore, SST is continuously developing and improving. Its future developments may well be depended on the addition of new social skill intervention components related to negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

The current study also found small to moderate effect size of SCIT in treating negative symptoms.34,41,42 Similarly, the effects of SCIT on negative symptoms may be attributable to several factors. Firstly, a number of previous studies have demonstrated that SCIT had a significant impact on emotion recognition of schizophrenia patients.32,33,43,44 The first stage of the SCIT protocol being emotion recognition training, which helps patients participants, improve their ability to identify others' emotions through facial expressions or tone of voice. Subsequently, patients participants may learn to identify and perceive their own and others' emotions more effectively, increasing their empathic abilities, thus alleviating emotional deficits associated with negative symptoms. Secondly, previous research suggested negative symptoms to be significantly associated with difficulties in theory of mind (ToM),45-47 and some previous studies found a strong relationship between inactive Type of ToM and negative symptoms,48-50 suggesting that improving a patient's participant's ToM may improve the dynamic deficits associated with negative symptoms. In regard of this finding, several studies reported that SCIT had a significant impact on levels of ToM.32,43 The second stage of SCIT intervention is "figuring out situations," which teaches patients participants how to recognize personal problems and improve their ability to infer the thoughts or intentions of others. Furthermore, negative symptoms were also associated with lower self-esteem, less self-serving bias, negative self-concepts related to interpersonal abilities, and dysfunctional acceptance beliefs.46

According to Wang et al. (2013), social skills and social cognition play a critical role in the recovery of social functioning in patients individuals with schizophrenia.51 In the procedure of SST, training of interpersonal communication and conversational skills reduced patients individuals’ asociality and poverty of speech, thus decreased their negative symptoms.9,20 In SCIT protocol, on the other hand, empathy and emotional expression are the main target which may be helpful in addressing anhedonia and affective expression deficiency.32,33,43,44 Regardless of the type of intervention, it is critical to pay attention to negative symptoms, as they are key to the recovery of social function.

In addition, digital psychiatry is on the rise.52 Studies that digitized SST and SCIT emerged, which applied computer-assisted interventions among clinical patients individuals.14 Although their efficacy still needs to be validated in larger samples. Digital interventions for social cognition currently focus on emotion recognition (ER) and ToM.50,53 Moreover, virtual reality technology can also be adjusted into procedures of both SST and SCIT. In one study, immersive virtual reality provided a safe learning environment for patients individuals who rejected social interaction, offering opportunities for them to practice social skills that were difficult to rehearse outside the virtual realm. This technology has been reported to have good tolerability and high patient participant satisfaction.54 Both computer-based digital intervention and VR-based intervention have the potential to improve the acceptability and universality of interventions and help individuals with schizophrenia better integrate into society.

This study is subject to two primary limitations. First, our relatively modest sample size restricts the generalizability of our findings. Future investigations with more extensive cohorts are essential to validate the impact of SST and SCIT on schizophrenia's negative symptoms. Second, our regression analysis failed to pinpoint any notable predictors that might determine the efficacy of the interventions on negative symptoms. This underscores the need for further research to unearth potential predictors that might influence the success of these treatments.

ConclusionBoth SST and SCIT have demonstrated efficacy in mitigating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, with SST emerging as the more robust approach. In light of these outcomes, there's a heightened need to prioritize addressing negative symptoms in rehabilitative interventions. Going forward, intervention strategies should emphasize elements that particularly address these negative symptoms.