Humanized care is the first aspect to consider to satisfy the surgical patient who will be or has undergone a surgical intervention.

ObjetiveDetermine the relationship that exists between perceived satisfaction and humanized nursing care in surgical patients in a public hospital in Peru.

MethodDescriptive, observational, correlational study, with a quantitative approach, with probabilistic sampling of 241 surgical patients. A validated questionnaire adapted to our reality was used, reporting a Cronbach Alpha coefficient of 0.890 (satisfaction) and 0.904 (humanized nursing care), presenting 36 multiple choice questions.

ResultsThe age group of 18−29 years predominated in 26.6% (n = 64), with the average age X = 42.6 years with a DS of 14.47, female sex with 55.2% (n = 133), single marital status 48.5% (n = 117) and secondary education level was 60.2% (n = 145). The majority of patients were satisfied with the care received, reporting 84.6% (n = 204), also found in the dimensions: Humane 81.8% (n = 197), timely 78.8% (n = 190) and safe 80.1% (n = 193). The perceived humanized nursing care was good 81.3% (n = 196), it was also evident in the dimensions: Phenomenological 78.4% (n = 189), interaction 75.9% (n = 183), scientific 61, 8% (n = 149) and human needs (82.2%) (n = 198).

ConclusionsA moderate correlation was found between the variables, behaving in a moderately positive manner, that is, the higher the level of satisfaction, the higher the level of humanized nursing care in the surgical patient, and vice versa.

El cuidado humanizado es el primer aspecto a considerar para satisfacer al paciente quirúrgico que será o ha sido sometido a una intervención quirúrgica.

ObjetivoDeterminar la relación que existe entre la satisfacción percibida y el cuidado humanizado de enfermería en pacientes quirúrgicos de un hospital público del Perú.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo, observacional, correlacional, con enfoque cuantitativo, con muestreo probabilístico de 241 pacientes quirúrgicos. Se utilizó un cuestionario validado y adaptado a nuestra realidad, reportando un coeficiente Alfa Cronbach de 0,890 (satisfacción) y 0,904 (cuidado humanizado de enfermería), presentando 36 preguntas de opción múltiple.

ResultadosPredomino el grupo etario de 18−29 años en un 26,6% (n = 64), siendo la edad promedio X¯ = 42,6 años, con una DE de 14,47, sexo femenino con un 55,2% (n = 133), estado civil soltero 48,5% (n = 117) y nivel educativo secundaria fue 60, 2% (n = 145). La mayoría de pacientes estuvo satisfecho con la atención recibida reportándose 84,6% (n = 204), hallándose también en las dimensiones: Humana 81,8% (n = 197), oportuna 78,8% (n = 190 ) y segura 80,1% (n = 193). El cuidado humanizado de enfermería percibido fue bueno 81,3% (n = 196), igualmente se evidenció en las dimensiones: Fenomenológica 78,4% (n = 189), interacción 75,9% (n = 183), científica 61,8% (n = 149) y necesidades humanas (82,2%) (n = 198).

ConclusionesSe halló correlación moderada entre las variables, comportándose de forma positiva moderada, es decir, que, a mayor nivel de satisfacion, mayor sera el nivel del cuidado humanizado de enfermería, en el paciente quirúrgico, y viceversa.

Palabra ClaveSatisfacción del paciente, asistencia quirúrgica, enfermería.

User satisfaction is an indicator of quality and studied at a global level but one of the challenges in clinical nursing care is to satisfy a high quality humanised care for the patient undergoing surgery and few studies exist that have assessed the satisfaction of this particular type of patient.

What does it contribute?A specific limited study conducted in Peru indicated that satisfaction and humanised nursing care were optimal, but the proportion of satisfaction was lower in the dimensions of satisfaction with timeliness and with scientific needs, indicating the need to establish improvement strategies.

Satisfaction is regarded as a vital component of quality in health, as considered and studied in different countrie1–3 Offering an optimal health service that currently fits in with the competitive times of a globalised era, therefore constitutes a great challenge for health institutions worldwide. In this sense, in 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) reaffirmed its commitment to achieve universal health coverage by 2030. This means that all everybody in the world needs to have access to optimal quality health services with preventive-promotional care, and rehabilitation.4

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) state that quality is an essential issue for universal health coverage. Each year, around 8.4 million deaths occur due to inadequate health care in underdeveloped countries, representing 15% of deaths. The WHO also points out that 10% of patients suffer harm when receiving medical care, and seven out of 100 hospitalised patients suffer from an infection associated with the health service.5

Despite the theoretical diversity about how to satisfy external users and the constant efforts made by health institutions to do so, studies show that there are gaps in dissatisfaction, with a negativity in the opinion of Spanish hospital users.6 A similar situation is shown in the trend at the Latin American level. In Peru, a study shows low satisfaction of health users in the five dimensions evaluated by the Servqual instrument.7

In its various initiatives to measure quality according to user satisfaction in health establishments, the Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA) reported problems of increasing dissatisfaction among users.8 Health professionals therefore play a vital role in providing quality care to users.

Furthermore, in Peru, it has been reported that there is an estimated deficit of 18 thousand doctors and 60 thousand nurses, coupled with organisational problems that lead to user dissatisfaction in health establishments. These have also increased due to inadequate working conditions and low salaries that cause poor performance of professionals, ultimately affecting patient recovery.9 As a result, the issue has recently become highly significant for the medical community.10

Patient satisfaction is the degree of user perceptions-expectations in relation to the medical services offered.8 Therefore, "the practice of care should be assessed within a human framework for the satisfaction of holistic needs",11 especially in nurses who care for surgical patients, considering that this profession means care in the face of health-illness, rehabilitation and health promotion. Nurses are present from the beginning to end. They observe, listen, appreciate, diagnose, monitor, manage, treat and cure, but, above all, nursing means care,12 i.e., care is the origin of nursing.13

One of the challenges that health professionals face is to provide humanised care, especially when technological advances occasion the depersonalisation of care.14 As a result, "humanistic care is not only the core of nursing work, but also the transmission of human nature and the embodiment of the humanistic spirit".15 Humanisation is present in every nursing process, since its essence is framed within care. Patient characteristics must therefore be considered not only for practical reasons, but also in compliance with the indicators for humane treatment to the user. This helps the nurse’s ability to communicate intersubjectively, and promotes their continuing professional development to provide humanised care at all times.13

The scientific knowledge, therapeutic relationship and technical capacity that the nursing professional maintains with patients are essential points for top quality and comforting care,16 which leads to patient satisfaction. Furthermore, "nursing professionals can also benefit from providing humanised care, achieving greater professional and even personal satisfaction".17 However, there are factors that contribute to dehumanisation in nursing care, cited by several studies such as work overload, cutting-edge technology, organisation, complex structures, training, stress, among others.18–20

For Watson (cited by Echevarría), one of the factors of dehumanisation is the administrative restructuring in the health system, where it is essential to rescue the spiritual, human and transpersonal aspect.21 In this context, the quality of service impacts satisfaction, and to provide optimal care, nurses face ethical challenges in daily practice.22 The 2021 review of the literature in Canada indicates that satisfaction and meaning in nursing work seems to be closely related to the development of humanistic care, highlighting within its findings that the working conditions of nurses must be improved to maintain humanistic care after graduation.23 In Chile in 2021, the results indicated a good perception of humanised care, emphasizing the dimension of the quality of nursing work as the best evaluated. Communication, however, was the weakest or least perceived dimension.24 In Peru in 2020, its findings showed that overall user satisfaction in a health facility was 60.3%, reporting satisfaction values in the security and empathy dimensions of 86.8% and 80.3% respectively. The highest level of dissatisfaction came from the tangible aspects dimension at 57.1%, and the response capacity of health services at 55.5%.2

We therefore considered it important, impactful and significant for the public health area to evaluate the satisfaction perceived by the surgical patient regarding human nursing care in a public institution in Peru today, where the development of technology causes the loss or limited assertive therapeutic communication that is the essence of humanised care. A priority would be to strengthen strategies that improve empathy and encourage communication between nurse and patient. Likewise, the study would provide relevant data, leading to rethinking aspects for the continuous improvement of humanised care, detecting deficiencies found based on expectations and perceptions identified by the surgical patient. The study consisted of determining the relationship between perceived satisfaction and humanised nursing care in surgical patients in a public hospital in Peru, identifying the relationship between the level of perceived satisfaction and the dimensions of humanised care in this type of patients and determining the sociodemographic characteristics.

MethodDescriptive and observational study. The population comprised all patients who underwent surgery in the surgical department of the Santa María del Socorro Hospital in Ica, Peru (HSMSI).

The study inclusion criteria were postoperative patients of legal age (18 years and older), hospitalised in the surgical department who underwent surgery for various general surgery pathologies such as appendectomies in all their phases: congestive, phlegmonous, perforated, including complications such as localised and generalised peritonitis, appendicular plastron; conventional and non-conventional cholecystectomies (laparoscopic cholecystectomy), hernioplasties: inguinal, umbilical, strangulated, incarcerated hernias, intestinal obstruction: mechanical and paralytic ileus, etc., as well as postoperative trauma patients (reduction plus osteosynthesis, lower limb amputation, etc.). Patients with an altered level of consciousness, with the effects of anaesthesia, and who voluntarily decided not to participate were excluded. From the postoperative patients in the HSMSI surgical service in 2022, the population of 644 was obtained. Selecting a sample of 241 surgical patients obtained using a formula for a finite population with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% and a precision of +/- 5 percentage units. The probabilistic method was used to select the sample. The main variable of the study was perceived satisfaction, an ordinal qualitative variable that was applied in parallel to the variable humanised nursing care using a Likert scale from 1 to 5: never (1), almost never (2), sometimes (3), almost always (4), and always (5). Using an instrument validated by López in 2017,25 for both variables. In July 2023, the pilot test was applied to 15% of the sample, reporting a Cronbach's Alpha reliability coefficient of .890 (satisfaction) and .904 (humanised care), considered acceptable in both instruments with a total of 36 questions (18 questions for each variable).

In August and October, a survey was carried out integrated into a questionnaire that consisted of three parts. Part one: sociodemographic data of surgical patients, referring to age, sex, origin, marital status and educational level. This information that was used to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. Part two: corresponded to the user satisfaction questionnaire, which was used to determine the perceived satisfaction of the surgical patient, validated25 with a Cronbach's Alpha reliability of .87. It had 18 questions divided into three dimensions, which offered information on perceived satisfaction in each one: (D1) human dimension (good treatment, personalised attention, if the nurse comes when you call that you need them, etc. D2: timely dimension (if they answer your questions in a timely manner about medications and inform you about institutional aspects and the doctor's report and (D3) safe dimension (if the nurse places safety rails to avoid accidents, concentration on the procedures, if they ask your name and identify you, etc. (with six questions each). The perceived satisfaction was analysed on three levels, with their scores determined according to the statistical interval technique, with equal proportions in each level: for global satisfaction: dissatisfied (18–42), moderately satisfied (43−66-) and satisfied (67−30). Regarding the dimensions the score was dissatisfied (6–14), moderately satisfied (15–22), and satisfied (23–90). Part three involved the humanised care questionnaire, used to establish humanised nursing care and obtain information about humanisation in care, validated by the same author,25 with a Cronbach's Alpha reliability of .727 with 18 questions divided into four dimensions: D1. Phenomenological (if they treat you with respect, kindness, patience, sensitivity, etc.) (four questions), D2: interaction (if there is active listening, communication with the patient, etc.) (five questions), D3: scientific (explanation to the patient about medication administered, adverse effects caused by medications, etc.) (four questions) and D4: human needs (facilitates care of basic health needs, food, bathing, comfort, etc.) (five questions). The questionnaire rating was determined with the interval statistical technique, with equal proportions in its three levels: poor overall humanised care (18–42), average (43–66), good (67–90). The dimensions had the following scores: poor (4–9), average (10–15), good (16–20)

The data obtained were analysed using the free-license SPSS version 25 statistical programme, performing a descriptive analysis, using the mean, standard deviation (SD) and minimum and maximum values for the relationship of variables that do not come from a normal distribution. Likewise, the non-parametric Spearman's Rho statistical test was used to analyse the relationship between categorical variables, satisfaction and humanised nursing care and its dimensions.

The study took into account the ethical considerations described in the Good Clinical Practice Guide, the Declaration of Helsinki, ethical principles of reliability, privacy, beneficence, non-beneficence and informed consent, which was signed by all participants. The study was approved by the Institution's Research Ethics Committee.

ResultsThe 18−29 years age group predominated at 26.6% (n = 64), with an average age of X¯ = 42., with a minimum age of 18 years and a maximum of 79 years and a SD of 14.47, female sex was 55.2% (n = 133), place of origin of 90.5% (n = 218) from the study site Ica, Peru, marital status single with 48.5% (n = 117) and secondary education level 60, 2% (n = 145).

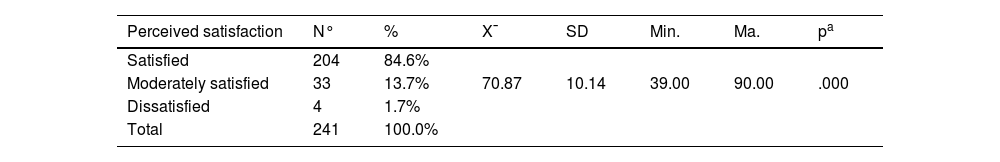

Eighty-four point six per cent (n = 204) of surgical patients were satisfied with the care received, 13.7% (n = 33) were moderately satisfied, and 1.7% (n = 4) were dissatisfied. According to the descriptive analysis of the variable, the arithmetic mean is 70.87 points, with a minimum value of 39.0 points and a maximum of 90.0 points, presenting a SD of ± 10.14. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistician determined that the data do not come from a normal distribution (p = .000) (Table 1).

Perceived satisfaction in surgical patients. Public Hospital of Peru.

| Perceived satisfaction | N° | % | X¯ | SD | Min. | Ma. | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied | 204 | 84.6% | |||||

| Moderately satisfied | 33 | 13.7% | 70.87 | 10.14 | 39.00 | 90.00 | .000 |

| Dissatisfied | 4 | 1.7% | |||||

| Total | 241 | 100.0% |

Surgical patients were satisfied according to the dimensions: humane 81.8% (n = 197), timely 78.8% (n = 190) and safe 80.1% (n = 193) (Table 2).

Perceived satisfaction according to dimensions, in surgical patients. Public Hospital of Peru.

| Dimensions of perceived satisfaction | N° | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Satisfied | 197 | 81.8% |

| Moderately satisfied | 41 | 17.0% | |

| Dissatisfied | 3 | 1.2% | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0% | |

| Timely | Satisfied | 190 | 78.8% |

| Moderately satisfied | 47 | 19.5% | |

| Dissatisfied | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0% | |

| Safe | Satisfied | 193 | 80.1% |

| Moderately satisfied | 44 | 18.2% | |

| Dissatisfied | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0% |

Eighty-one point three per cent 81.3% (n = 196) of surgical patients perceived that humane nursing care was good, 16.2% (n = 39) average, and 2.5% (n = 6) bad. According to descriptive analysis of the variable, the arithmetic average was 75.19 points, with a minimum value of 38.0 points and a maximum of 90.0 points, presenting a SD of 10.89. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic determined that the data did not come from a normal distribution (p = .000) (Table 3).

Humanised nursing care perceived by surgical patients. Public Hospital of Peru.

| Humanised care | N° | % | X¯ | SD | Min. | Max. | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |Good | 196 | 81.,3% | 75.19 | 10.89 | 38.00 | 90.00 | .000 |

| Average | 39 | 16.2% | |||||

| Poor | 6 | 2.% | |||||

| Total | 241 | 100.0% |

A greater predominance of satisfaction with the care received was observed in patients who perceived that humanised care is good 78.0% (n = 188). Likewise, it was observed that medium satisfaction was more frequent in those who perceived that humanised care was average 9.6% (n = 23). Regarding dissatisfaction, a higher proportion was found in patients who considered that humanised care was deficient 1.7% (n = 4). The Spearman Rho statistical test found a moderate correlation between the variables (r = .668, p = .000), behaving in a moderately positive manner, meaning that the higher the level of humanised nursing care, the higher the level of patient satisfaction and vice versa (Table 4).

Relationship between perceived satisfaction and humanised nursing care in surgical patients. Public Hospital of Peru.

| Perceived satisfaction | Humanised nursing care | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Average | Poor | ||||||

| N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | |

| Satisfied | 188 | 78.0% | 16 | 6.6% | 0 | .0% | 204 | 84.6% |

| Moderately satisfied | 8 | 3.3% | 23 | 9.6% | 2 | .8% | 33 | 13.7% |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | .0% | 0 | .0% | 4 | 1.7% | 4 | 17% |

| Total | 196 | 81.3% | 39 | 16.2% | 6 | 2.5% | 241 | 100.0% |

It was observed that there was a moderate positive correlation between perceived satisfaction and the dimensions of humanised nursing care: phenomenological (r .643, p = .000), interaction (r = .652, p = .000), scientific (r = .565, p = .000), and human needs (r = .620, p = .000), with satisfaction predominating in surgical patients who considered these dimensions to be good (Table 5).

Relationship between perceived satisfaction and the dimensions of humanised nursing care in surgical patients. Public Hospital of Peru.

| Perceived satisfaction | Phenomenological dimension | Total | Sp Rho | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Average | Poor | |||||||

| N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | r = 643ap = .000 | |

| Satisfied | 183 | 75.9% | 19 | 7.9% | 2 | .8% | 204 | 84.6% | |

| Moderately Satisfied | 6 | 2.5% | 26 | 10.8% | 1 | .4% | 33 | 13,7% | |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 1.2% | 1 | .4% | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 189 | 78.4% | 48 | 19.9% | 4 | 1.7% | 241 | 100.0% | |

| Perceived satisfaction | Interaction dimension | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Average | Poor | |||||||

| N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | ||

| Satisfied | 179 | 74.2% | 25 | 10.4% | 0 | .0% | 204 | 84.6% | r = .652ap = .000 |

| Moderately Satisfied | 4 | 1.7% | 28 | 11.6% | 1 | .4% | 33 | 13.7% | |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | .0% | 1 | .4% | 3 | 1.2% | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 183 | 75.9% | 54 | 22.4% | 4 | 1.7% | 241 | 100.0% | |

| Perceived satisfaction | Scientific dimension | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Average | Poor | |||||||

| N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | r = .565ap.000 | |

| Satisfied | 145 | 60.2% | 59 | 24.5% | 0 | .0% | 204 | 84.6% | |

| Moderately Satisfied | 4 | 1.7% | 26 | 10.8% | 3 | 1.2% | 33 | 13.7% | |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | .0% | 0 | .0% | 4 | 1.7% | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 149 | 61.8% | 85 | 35.3% | 7 | 2.9% | 241 | 100.0% | |

| Perceived satisfaction | Human needs dimension | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Average | Poor | |||||||

| N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | r = .620ap = .000 | |

| Satisfied | 189 | 78.4% | 15 | 6.2% | 0 | .0% | 204 | 84.6% | |

| Moderately Satisfied | 9 | 3,8% | 22 | 9,1% | 2 | .8% | 33 | 13.7% | |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | .0% | 3 | 1.3% | 1 | .4% | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 198 | 82.2% | 40 | 16.6% | 3 | 1.2% | 241 | 100.0% | |

One of the challenges of clinical practice for nurses is to provide satisfactory humanised, high-quality care for the surgical patient.

As a result, “humanistic care has become a global concern in nursing education”.15 and “satisfaction and the meaning of nursing work therefore seem to be closely related to humanistic development.”23

Regarding the findings of the first variable satisfaction, surgical patients were mostly satisfied with the humane care received, and these data coincide with a study in Iran, which indicates that patients were very satisfied with humane care in critical care units.11 Likewise, the results are similar to studies in Ecuador, Havana, and with studies in Peru, which reported a predominance of satisfaction in patients who received nursing care.1,10 No similarity was found with other research, which found a low level of user satisfaction with nursing care.6,7

We would therefore highlight that “user satisfaction is an indicator of the quality of care provided in the health area”,3 and that “quality of care affects satisfaction”. Regarding perceived satisfaction according to the human dimension, surgical patients were satisfied, stating that there was good treatment and patience from the nurse when caring for them. In the timely dimension, satisfaction was also found, in which patients perceived that nurses answered their questions about medications, and that they received information on institutional aspects and a report from the doctor. Satisfaction also predominated in the safety dimension, in which patients stated that nurses placed safety railings to avoid accidents, among others. These results show similarity with the study in Iran, which concludes that patients showed satisfaction with humanised treatment in the dimensions evaluated. However, it is recommended to reinforce the skills of nurses, especially regarding information and effective communication with patients.11 Another study in Peru reported that satisfaction according to the human, timely and safety dimensions was perceived more predominantly by users as moderately satisfactory.26

Regarding the perception of humanised nursing care, the research reported that patients predominantly received a good level of it. This variable was measured in three levels: good, average and poor. These results were similar to various studies that categorise behaviours of humanised nursing care as good, adequate, excellent and constant. Nurses satisfy the patient with human care in medical-surgical units and hospitalisation services.16,19,21,24,27 This is not consistent with another study where it concludes that human nursing care in the hospitalisation service is average.28

Similarly, in China, the study concluded that the humanistic care capacity of nursing students was poor and was positively associated with emotional intelligence and empathy, characteristics that are vital to providing humane care.15 We therefore consider that nursing is the essence of care, as research indicates, "humanised care must practice the values of empathy, solidarity, and respect, among others." 20 Regarding the results of humanised care according to dimensions and perceived satisfaction in surgical patients, the Rho Spearman correlation analysis was used, observing that there is a moderate positive correlation according to phenomenological care, interaction, scientific care and human needs, with satisfaction predominating in surgical patients who considered these dimensions to be good, with the behaviour of said relationship being direct, that is, the greater the satisfaction of these dimensions of humanised nursing care, the greater the satisfaction in the surgical patient and vice versa. Examining these dimensions, the majority of patients had a positive opinion of the care regarding: human needs (basic health needs, food, bathing, convenience, etc.), phenomenological (good treatment, patience, sensitivity, etc.), interaction (active listening, communication) and scientific dimension (explanation to the patient about the medication administered, adverse effects caused by the medications, etc.), which is consistent with Jean Watson, the leading exponent of the theory of humanised care.29 These results were similar to those reported by another study, which indicates that it found an association between the level of satisfaction and the perception of humanised care, and according to its dimensions: qualities of nursing practice, openness to communication and willingness to provide care.10 Similarly, the study in Chile indicates that there is a good appreciation of humanised care and the quality of nursing work, stating that the quality of the task dimension was the best evaluated, and communication was the best perceived.24 However, one study reported an intermediate level in all dimensions of humanised care, and according to the order of priority they were: scientific, phenomenological and interaction and human needs.25

Regarding the relationship between perceived satisfaction and humanised nursing care in general, the Spearman Rho test was also applied, finding in the study a significant correlation, behaving in a moderately positive way, that is, the higher the level of humanised care, the higher the level of satisfaction in patients, showing consistency with studies that conclude that they feel satisfied with the humane treatment provided,1 and that there is a significant association between perception of care and the level of satisfaction.10 However, other studies show that there is no relationship between these variables.26 We highlight in the study that surgical patients perceived themselves to be satisfied with human nursing care in all its dimensions, rated as good, demonstrating strength, but that this human and empathetic care between the nurse-patient binomial must be sustained over time to favour the patient's recovery, and that nursing managers must formulate strategies to sustain it.

As limitations we could consider that the study data collected involved postoperative patients from a public institution in Peru and that it is feasible that the results are not fully generalisable to all postoperative patients in the surgical service, and therefore, to all surgical patients.

In conclusion, the Spearman Rho statistical test found a moderate correlation between the variables, behaving in a moderately positive way and therefore proving that the higher the level of humanised nursing care, the higher the level of satisfaction in the surgical patient, and vice versa.

It was also found, according to the statistical test mentioned above, that there was a positive moderate statistical correlation between perceived satisfaction and the dimensions of humanised nursing care: phenomenological, interaction, scientific and human needs, with satisfaction predominating in surgical patients, who considered these dimensions to be of a good level.

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, surgical patients were predominantly in the 18−29 year age group and were female, single, with a secondary educational level.

FundingThis research received no funding from public or private entities.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Our thanks to all participating patients, without whose opinion and participation this study would not have been possible. Also to the HSMI Surgical Service for its institutional support. To the Vice-Rectorate of Research of the Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga, Ica, Peru for its support and collaboration that enables us as research professors, to continue making our reality known.