To estimate the incidence of pneumonia diagnosis in elderly patients in Spanish emergency departments (ED), need for hospitalization, adverse events and predictive capacity of biomarkers commonly used in the ED.

MethodsPatients ≥65 years with pneumonia seen in 52 Spanish EDs were included. We recorded in-hospitaland 30-day mortality as adverse events, as well as intensive care unit (ICU) admission among hospitalizedpatients. Association of 10 predefined variables with adverse events was calculated and expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), as well as predictive capacity of 5 commonly used biomarkers in the ED (leukocytes, hemoglobin, C-reactive protein, glucose, creatinine) was investigated using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC).

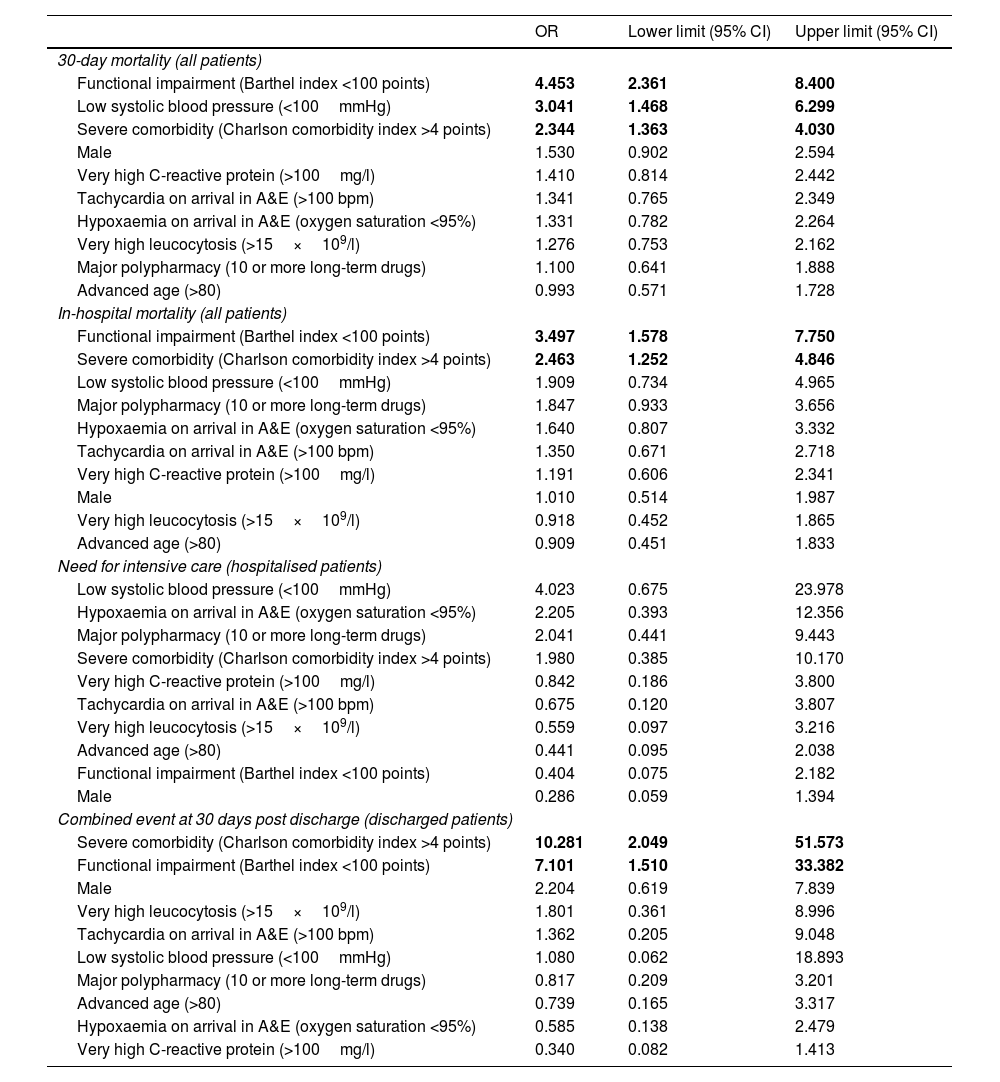

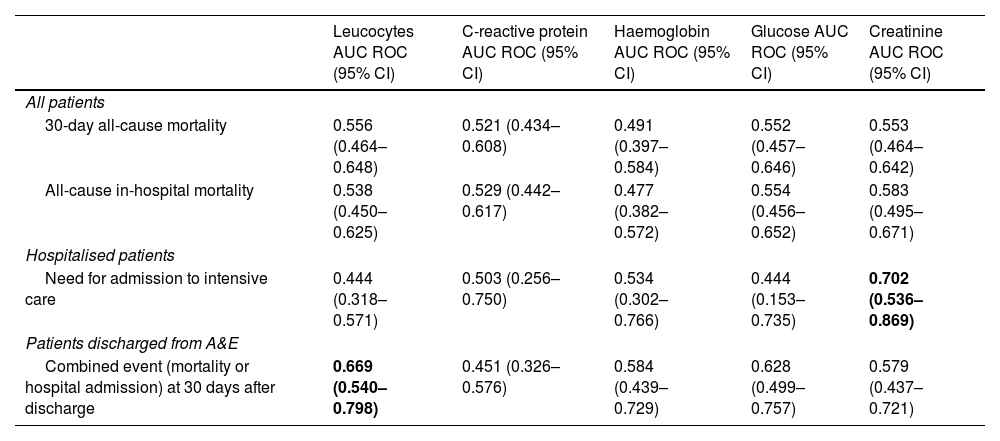

Results591 patients with pneumonia attended in the ED were included (annual incidence of 18,4 per 1000 inhabitants). A total of 78.0% were hospitalized. Overall, 30-day mortality was 14.2% and in-hospital mortality was 12.9%. Functional dependency was associated with both events (OR=4.453, 95%CI=2.361–8.400; and OR=3.497, 95%CI=1.578–7.750, respectively) as well as severe comorbidity (2.344, 1.363–4.030, and 2.463, 1.252–4.846, respectively). Admission to the ICU during hospitalization occurred in 3.5%, with no associated factors. The predictive capacity of biomarkers was only moderate for creatinine for ICU admission (AUC-ROC=0.702, 95% CI=0.536–0.869) and for leukocytes for post-discharge adverse event (0.669, 0.540–0.798).

ConclusionsPneumonia is a frequent diagnosis in elderly patients consulting in the ED. Their functional dependence and comorbidity is the factor most associated with adverse events. The biomarkers analyzed do not have a good predictive capacity for adverse events.

Estimar la incidencia de diagnóstico de neumonía en pacientes mayores en los servicios de urgencias (SU) españoles, necesidad de hospitalización, eventos adversos y capacidad predictiva de biomarcadores.

MétodosSe incluyeron pacientes de ≥65 años con neumonía atendidos en 52 SUespañoles. Como eventos adversos, se recogió mortalidad intrahospitalaria y a los 30 días, ingreso en unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI). Se calcularon las odds ratio (OR) ajustadas con su intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC95%) de estos eventos y se investigó la capacidad predictiva de 5 biomarcadores de uso habitual en urgencias (leucocitos, hemoglobina, proteína-C reactiva, glucosa, creatinina) mediante área bajo la curva de la característica operativa del receptor (ABC-COR).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 591 pacientes con neumonía (incidencia anual de 18,4 por 1000 habitantes). El 78,0% fue hospitalizado. La mortalidad global a 30 días fue del 14,2% y la intrahospitalaria del 12,9%. La dependencia funcional se asoció a ambos eventos (OR=4,453, IC95%=2,361–8,400; y OR=3,497, IC95%=1,578–7,750, respectivamente) así como la comorbilidad grave (2,344, 1,363–4,030, y 2,463, 1,252–4,846, respectivamente). El ingreso en UCI durante la hospitalización aconteció en el 3,5%. La capacidad predictiva de los biomarcadores solo resultó moderada para creatinina para ingreso en UCI (ABC-COR=0,702, IC 95%=0,536–0,869) y para leucocitos para evento adverso post-alta (0,669, 0,540–0,798).

ConclusionesLa neumonía es un diagnóstico frecuente en los pacientes mayores que consultan en SU. Su situación basal, especialmente dependencia funcional y comorbilidad, es el factor que más se asocia a eventos adversos. Los biomarcadores analizados no tienen buena capacidad individual predictiva de eventos adversos.

Pneumonia is a major cause of death overall in developed countries and the most common cause of infectious origin, as well as the leading cause of severe sepsis and septic shock.1 It is a common diagnosis which often leads to consultations in accident and emergency departments (A&E). In 2019, the annual incidence of hospital admissions due to pneumonia in Spain was 3.9 cases per 1000 population.2 This incidence increases with the age of the patients; 70% of hospital admissions are of patients over 65, in whom the annual incidence is 13.8 admissions per 1000 population.2 According to European and North American studies, it can reach an incidence of 25–40 cases per 1000 population/year and a mortality rate in the range of 7%–35% in patients aged over 65.3

The study of pneumonia has frequently focused on the aetiological, clinical, microbiological and therapeutic aspects.4 Fewer studies have been carried out from the perspective of patients diagnosed in A&E and virtually none focus on epidemiological aspects and care organisation in the context of this disease. A&E offers a closer perspective on the universe of pneumonia than that offered by the hospitalised patient, as not all pneumonia evaluated in A&E will ultimately be admitted to hospital. It is thought that only 20%–40% of patients with community-acquired pneumonia in the general population require hospital admission.2,5 The aims of this study were to estimate the incidence of pneumonia diagnosis in older adult patients in Spanish A&E, the need for hospitalisation and associated factors, and take a closer look at diagnostic confirmation of the diagnosis among hospitalised patients and associated factors, adverse events and associated factors, and the ability of various biomarkers commonly used in A&E to estimate these adverse events.

Material and methodsDesign of the EDEN registry and the EDEN-29 studyThe primary objective of the multipurpose Emergency Department and Elder Needs (EDEN) registry is to expand knowledge about sociodemographic, organisational, baseline, clinical, healthcare and outcome aspects of the population aged over 65 who visit Spanish A&E departments. Fifty-two A&E departments in 14 of Spain's autonomous regions participated in the creation of the EDEN registry, representing 17% of the public hospital A&E departments in Spain and covering 25% of the Spanish population (11,768,548 people). The participating A&E departments included all patients over 65 seen between 1 and 7 April 2019 (seven days), regardless of the reason for consultation. There was no reason for exclusion. The details of the EDEN registry have been described at greater length previously.6

The EDEN-29 study included patients from the EDEN cohort with diagnostic coding corresponding to pneumonia (ICD-10 codes: 480, 481, 482.9, 484, 485, 486, J12.0, J12.1, J12.89, J12.9, J13, J15.0, J15.1, J15.212, J15.8, J15.9, J16.8, J17, J18.0, J18.1, J18.8, J18.9). The diagnoses recorded at hospital discharge in the admitted patients were also collected. The EDEN-29 study had four endpoints: 1) determine the incidence of pneumonia diagnosis in Spanish A&E departments adjusted to the reference population of said A&E; 2) analyse the frequency and factors associated with hospital admission; 3) analyse the frequency and factors associated with diagnostic confirmation in hospitalised patients; and 4) explore the factors associated with adverse events and the ability of a series of biomarkers available in A&E to predict them.

Independent variablesTwenty-eight independent variables were collected, which included two sociodemographic factors (age, gender), nine comorbidity factors (Charlson comorbidity index [CCI], hypertension, diabetes mellitus, active cancer, heart failure, coronary heart disease, chronic lung disease, cerebrovascular disease, moderate/severe chronic kidney disease [defined in line with previous studies as patients with a prior recorded creatinine ≥2mg/ml]),7 seven baseline status factors (Barthel index [BI], number of long-term medications, need for help with walking, falls in the previous six months, previous diagnosis of depression, dementia or delirium), five about the patient's clinical status in A&E (systolic blood pressure [SBP], heart rate, basal oxygen saturation, fever if the temperature was >37.3°C, decreased consciousness) and five biomarkers associated with mortality and routinely determined in the majority of patients treated in A&E: leucocytes, C-reactive protein (CRP), creatinine, blood glucose and haemoglobin. Other prognostic biomarkers, such as procalcitonin or lactate, are not routinely requested in A&E for a patient with pneumonia, which is why it was decided not to include them.

Adverse eventsAll-cause mortality 30 days after the index event and in-hospital mortality were recorded. In hospitalised patients, the need for admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) was recorded and, for those who were discharged (not deceased during the index episode), the combined variable of death or need for hospital admission for any cause during the 30 days of post-discharge follow-up.

Statistical analysisThe median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe the quantitative variables, and absolute values and percentages for the qualitative variables. The characteristics of the patients with pneumonia were compared using the Mann-Whitney test for quantitative variables, and the χ2 test for qualitative variables. The estimation of the incidence of pneumonia diagnosis in Spanish A&E was carried out per year and 1000 population (considering the reference population assigned to each of the 52 participating A&E departments and a constant incidence of pneumonia throughout the year), and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated from the estimation of incidence using the Clopper-Pearson exact binomial method.

To identify the factors associated with adverse events, two approaches were used. The first consisted of investigating the relationship they had with 10 variables defined beforehand as potentially related to said adverse events, prior to the continuous variables using cut-off points with clinical significance or those which are commonly used. These were: advanced age (>80), gender, some degree of functional impairment (BI<100 points, which is not synonymous with functional dependence, considered to be scores of 60 or lower); severe comorbidity (CCI>4 points); major polypharmacy (>9 long-term drugs); tachycardia (>100 bpm); low systolic blood pressure (<100mmHg); and hypoxaemia (oxygen saturation <95%) on arrival at A&E; and very high leucocytosis or CRP (>15×109/l and >100mg/l respectively). To do this, a multivariate logistic regression model was used for explanatory purposes in which the introduction of the 10 variables was forced and the adjusted odds ratio (OR) with its 95% CI was recorded. The missing values of the variables introduced into the model were replaced by the mode or median, depending on whether they were qualitative or quantitative respectively. The second approach consisted of investigating the predictive capacity of the previously defined biomarkers available in any A&E and frequently used to estimate patient severity for each of the adverse events studied. To do this, the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was calculated, with its 95% CI. All biomarkers were considered quantitatively, and there was no imputation of missing values.

Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05, the 95% CI of the OR excluded the value 1 or the 95% CI of the AUC ROC excluded the value 0.5. All statistical processing was performed using the statistical package SPSS Statistics V26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical considerationsThe EDEN project was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid (protocol HCSC/22/005-E). The creation of the EDEN cohort and the work emanating from it has adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki at all times.

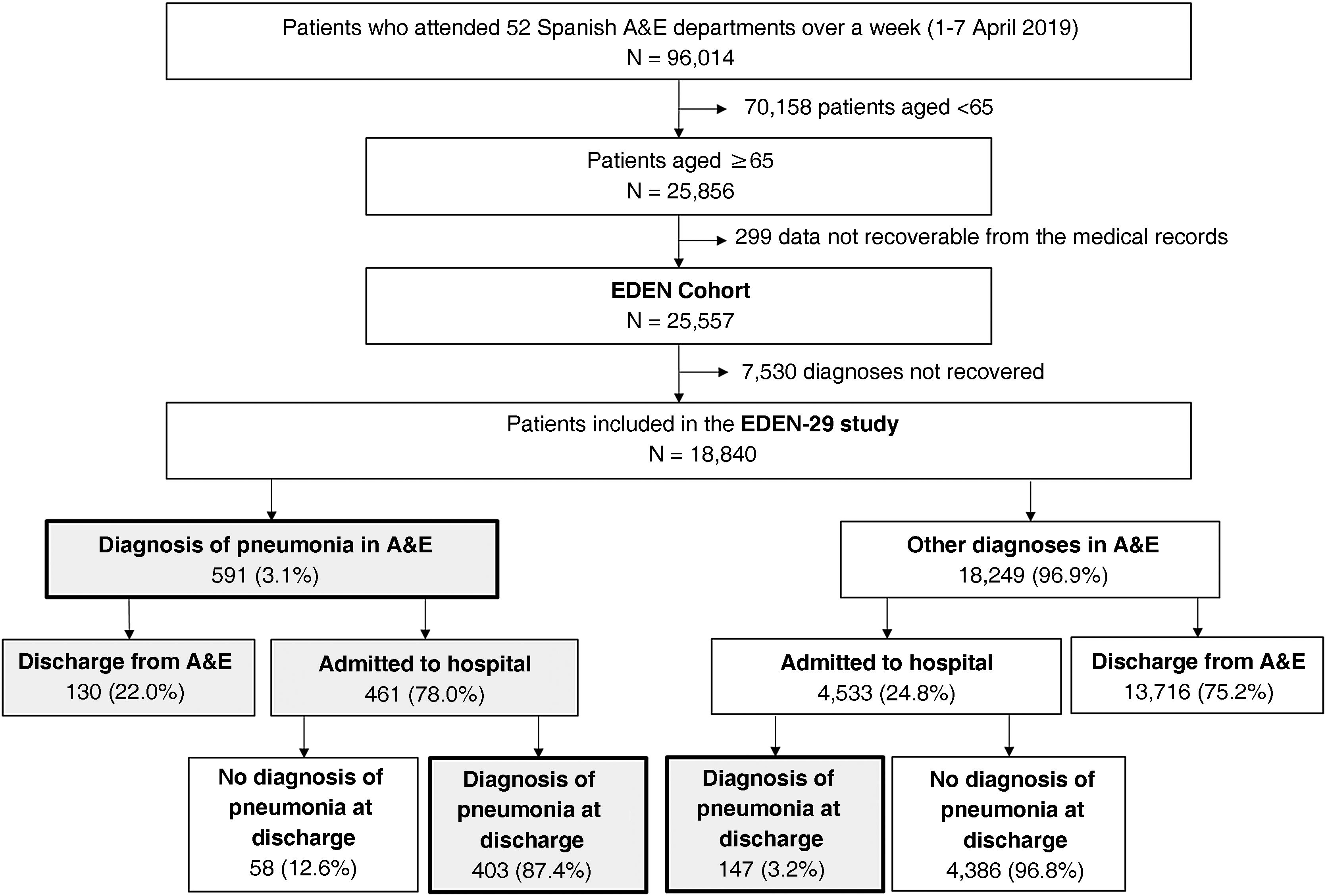

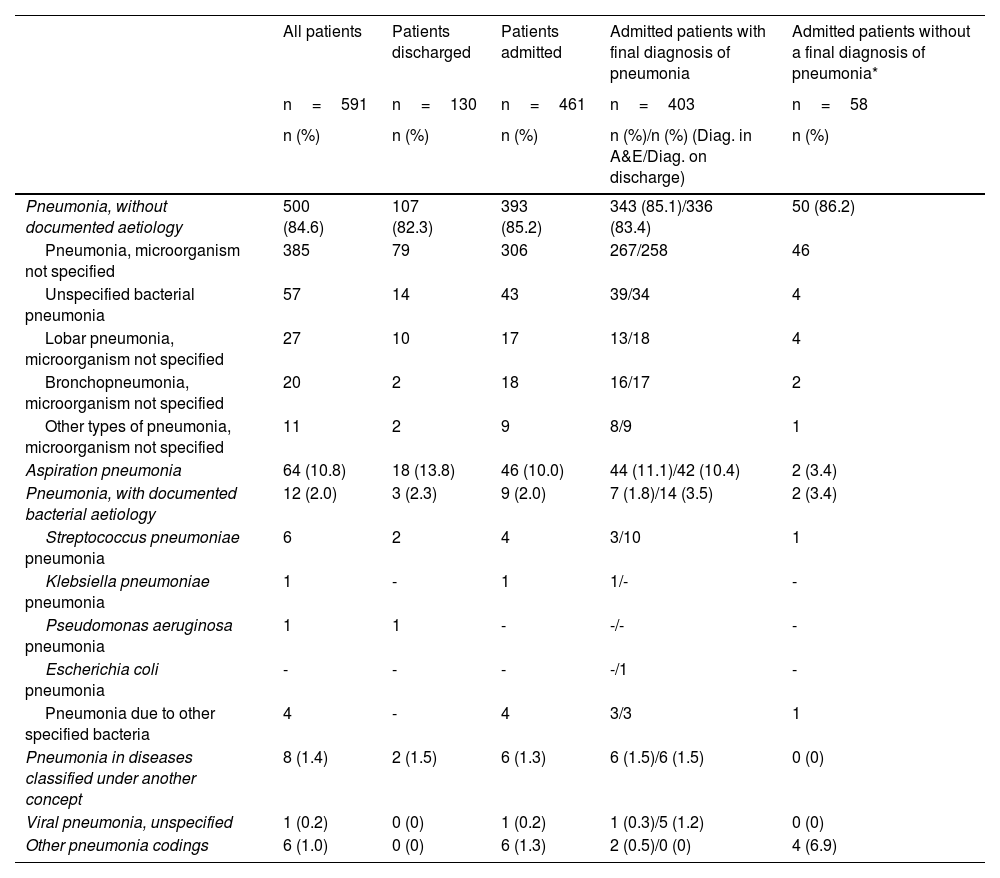

ResultsA total of 591 patients diagnosed with pneumonia in A&E were included (Fig. 1). Considering a constant incidence of pneumonia throughout the year, and that the inclusion period was seven days, that the 52 hospital A&E departments provide coverage to a total population of 11,768,548 people, that in 2019 (the year of the study) 19.3% of the Spanish population was aged over 65, and that 73.4% of patients treated in the 52 A&E departments were coded, the estimated annual incidence of pneumonia diagnoses in Spanish A&E departments in this study was 18.4 per 1,000 population aged over 65 (95% CI of 17.0 to 19.9 cases per 1,000). The diagnoses by large aetiological groups of pneumonia are shown in Table 1. Of the patients with pneumonia, 78% were admitted to hospital (with no differences in the type of pneumonia between hospitalised and non-hospitalised; P=.611) and in 87.4% of the admitted patients, the diagnosis of pneumonia was included in both reports (A&E and admission), with no differences found in the type of pneumonia (P=.212; Table 1). In hospitalised patients in whom the diagnosis of pneumonia was not included in the hospital discharge report (58 patients, 12.6% of cases), the most common diagnoses were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or bronchiectasis with acute exacerbation or acute lower respiratory tract infection (14 cases, 24.1%), unspecified lower respiratory tract infection (13 cases, 22.4%) and unspecified respiratory disorders (13 cases, 22.4%; Table 1). Last of all, of the 4,533 admitted patients with no diagnosis of pneumonia recorded in the A&E report, 147 (3.2%) had a pneumonia diagnosis in the discharge report at the end of their hospital stay (Fig. 1).

Diagnostic groups coded in the A&E report for the 591 patients diagnosed with pneumonia in A&E included in the EDEN-29 study.

| All patients | Patients discharged | Patients admitted | Admitted patients with final diagnosis of pneumonia | Admitted patients without a final diagnosis of pneumonia* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=591 | n=130 | n=461 | n=403 | n=58 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%)/n (%) (Diag. in A&E/Diag. on discharge) | n (%) | |

| Pneumonia, without documented aetiology | 500 (84.6) | 107 (82.3) | 393 (85.2) | 343 (85.1)/336 (83.4) | 50 (86.2) |

| Pneumonia, microorganism not specified | 385 | 79 | 306 | 267/258 | 46 |

| Unspecified bacterial pneumonia | 57 | 14 | 43 | 39/34 | 4 |

| Lobar pneumonia, microorganism not specified | 27 | 10 | 17 | 13/18 | 4 |

| Bronchopneumonia, microorganism not specified | 20 | 2 | 18 | 16/17 | 2 |

| Other types of pneumonia, microorganism not specified | 11 | 2 | 9 | 8/9 | 1 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 64 (10.8) | 18 (13.8) | 46 (10.0) | 44 (11.1)/42 (10.4) | 2 (3.4) |

| Pneumonia, with documented bacterial aetiology | 12 (2.0) | 3 (2.3) | 9 (2.0) | 7 (1.8)/14 (3.5) | 2 (3.4) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3/10 | 1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia | 1 | - | 1 | 1/- | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia | 1 | 1 | - | -/- | - |

| Escherichia coli pneumonia | - | - | - | -/1 | - |

| Pneumonia due to other specified bacteria | 4 | - | 4 | 3/3 | 1 |

| Pneumonia in diseases classified under another concept | 8 (1.4) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (1.3) | 6 (1.5)/6 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Viral pneumonia, unspecified | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3)/5 (1.2) | 0 (0) |

| Other pneumonia codings | 6 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.3) | 2 (0.5)/0 (0) | 4 (6.9) |

Diag.: diagnosis.

The main diagnoses of the 58 patients admitted to hospital for pneumonia for whom the diagnosis of pneumonia was not coded in the hospital discharge report were as follows: unspecified lower respiratory tract infection (13); unspecified respiratory disorders (13); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute exacerbation or acute lower respiratory tract infection (8); bronchiectasis with acute exacerbation or acute lower respiratory tract infection (6); acute respiratory failure (6); pleural effusion (3); sepsis/septic shock (3); lung cancer (2); acute bronchitis (2); pulmonary tuberculosis (1); pulmonary aspergillosis (1).

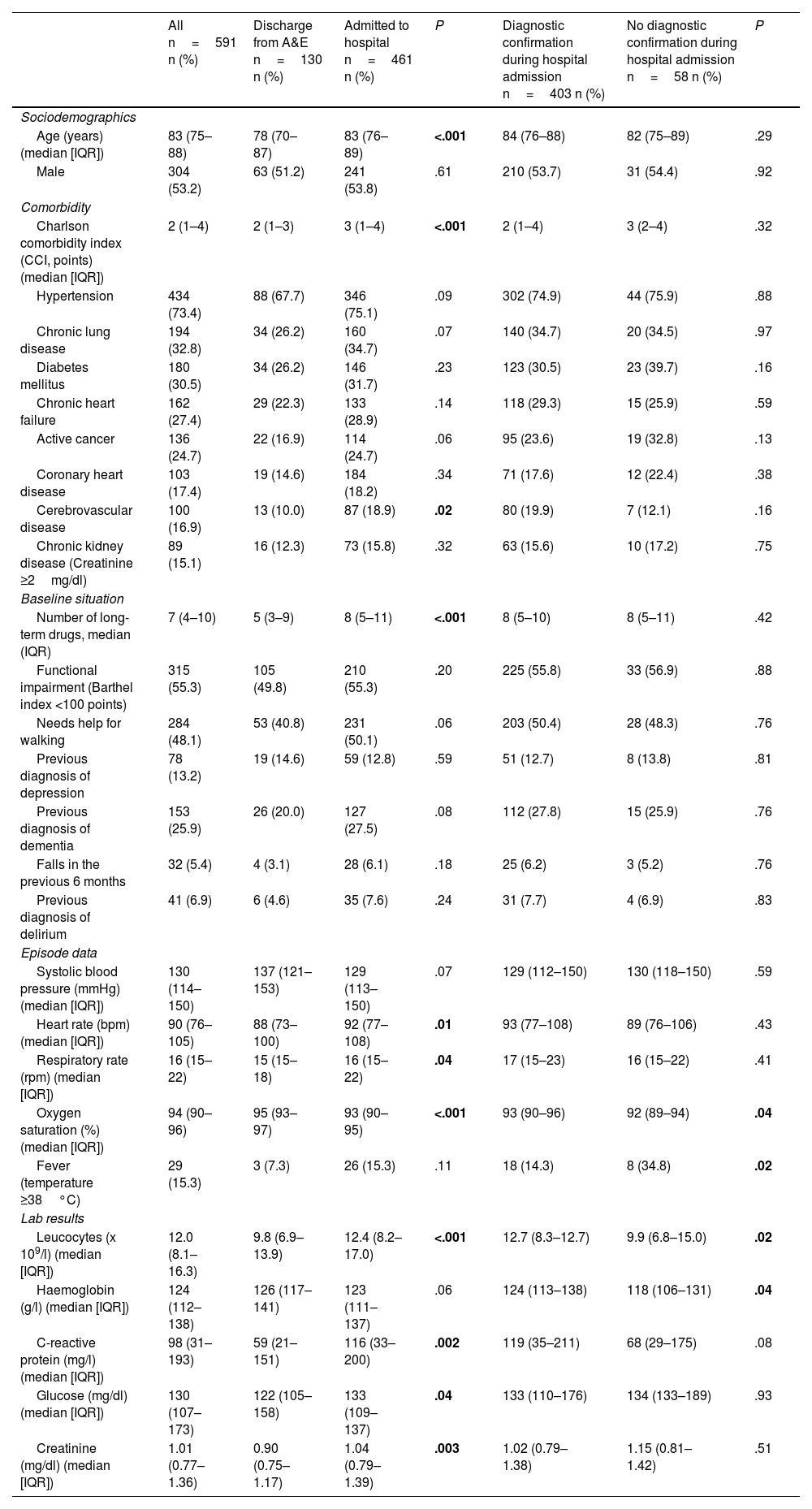

The median age was 83, 53.2% were male, comorbidity was common (severe in 22.3%, with CCI>4 points), with an altered functional status (BI<100 points) in more than 50% of the cases. The rest of the clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2. Hospitalised patients were older and had greater comorbidity and functional and analytical deterioration than patients discharged from A&E (Table 2). Among hospitalised patients, the lack of A&E confirmation of pneumonia diagnosis in the hospital discharge report was not associated with demographic, comorbidity or baseline status variables, and was only associated with having more hypoxaemia and more fever as clinical variables, and with having less leucocytosis and more anaemia as analytical variables (Table 2).

Analysis of the characteristics of patients diagnosed with pneumonia in A&E in the EDEN-29 study, and comparative analysis based on destination after emergency care (discharge/hospital admission) and whether or not the diagnosis was confirmed in the hospitalised patient.

| All n=591 n (%) | Discharge from A&E n=130 n (%) | Admitted to hospital n=461 n (%) | P | Diagnostic confirmation during hospital admission n=403 n (%) | No diagnostic confirmation during hospital admission n=58 n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||||||

| Age (years) (median [IQR]) | 83 (75–88) | 78 (70–87) | 83 (76–89) | <.001 | 84 (76–88) | 82 (75–89) | .29 |

| Male | 304 (53.2) | 63 (51.2) | 241 (53.8) | .61 | 210 (53.7) | 31 (54.4) | .92 |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Charlson comorbidity index (CCI, points) (median [IQR]) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–4) | <.001 | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–4) | .32 |

| Hypertension | 434 (73.4) | 88 (67.7) | 346 (75.1) | .09 | 302 (74.9) | 44 (75.9) | .88 |

| Chronic lung disease | 194 (32.8) | 34 (26.2) | 160 (34.7) | .07 | 140 (34.7) | 20 (34.5) | .97 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 180 (30.5) | 34 (26.2) | 146 (31.7) | .23 | 123 (30.5) | 23 (39.7) | .16 |

| Chronic heart failure | 162 (27.4) | 29 (22.3) | 133 (28.9) | .14 | 118 (29.3) | 15 (25.9) | .59 |

| Active cancer | 136 (24.7) | 22 (16.9) | 114 (24.7) | .06 | 95 (23.6) | 19 (32.8) | .13 |

| Coronary heart disease | 103 (17.4) | 19 (14.6) | 184 (18.2) | .34 | 71 (17.6) | 12 (22.4) | .38 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 100 (16.9) | 13 (10.0) | 87 (18.9) | .02 | 80 (19.9) | 7 (12.1) | .16 |

| Chronic kidney disease (Creatinine ≥2mg/dl) | 89 (15.1) | 16 (12.3) | 73 (15.8) | .32 | 63 (15.6) | 10 (17.2) | .75 |

| Baseline situation | |||||||

| Number of long-term drugs, median (IQR) | 7 (4–10) | 5 (3–9) | 8 (5–11) | <.001 | 8 (5–10) | 8 (5–11) | .42 |

| Functional impairment (Barthel index <100 points) | 315 (55.3) | 105 (49.8) | 210 (55.3) | .20 | 225 (55.8) | 33 (56.9) | .88 |

| Needs help for walking | 284 (48.1) | 53 (40.8) | 231 (50.1) | .06 | 203 (50.4) | 28 (48.3) | .76 |

| Previous diagnosis of depression | 78 (13.2) | 19 (14.6) | 59 (12.8) | .59 | 51 (12.7) | 8 (13.8) | .81 |

| Previous diagnosis of dementia | 153 (25.9) | 26 (20.0) | 127 (27.5) | .08 | 112 (27.8) | 15 (25.9) | .76 |

| Falls in the previous 6 months | 32 (5.4) | 4 (3.1) | 28 (6.1) | .18 | 25 (6.2) | 3 (5.2) | .76 |

| Previous diagnosis of delirium | 41 (6.9) | 6 (4.6) | 35 (7.6) | .24 | 31 (7.7) | 4 (6.9) | .83 |

| Episode data | |||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) (median [IQR]) | 130 (114–150) | 137 (121–153) | 129 (113–150) | .07 | 129 (112–150) | 130 (118–150) | .59 |

| Heart rate (bpm) (median [IQR]) | 90 (76–105) | 88 (73–100) | 92 (77–108) | .01 | 93 (77–108) | 89 (76–106) | .43 |

| Respiratory rate (rpm) (median [IQR]) | 16 (15–22) | 15 (15–18) | 16 (15–22) | .04 | 17 (15–23) | 16 (15–22) | .41 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) (median [IQR]) | 94 (90–96) | 95 (93–97) | 93 (90–95) | <.001 | 93 (90–96) | 92 (89–94) | .04 |

| Fever (temperature ≥38°C) | 29 (15.3) | 3 (7.3) | 26 (15.3) | .11 | 18 (14.3) | 8 (34.8) | .02 |

| Lab results | |||||||

| Leucocytes (x 109/l) (median [IQR]) | 12.0 (8.1–16.3) | 9.8 (6.9–13.9) | 12.4 (8.2–17.0) | <.001 | 12.7 (8.3–12.7) | 9.9 (6.8–15.0) | .02 |

| Haemoglobin (g/l) (median [IQR]) | 124 (112–138) | 126 (117–141) | 123 (111–137) | .06 | 124 (113–138) | 118 (106–131) | .04 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) (median [IQR]) | 98 (31–193) | 59 (21–151) | 116 (33–200) | .002 | 119 (35–211) | 68 (29–175) | .08 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) (median [IQR]) | 130 (107–173) | 122 (105–158) | 133 (109–137) | .04 | 133 (110–176) | 134 (133–189) | .93 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) (median [IQR]) | 1.01 (0.77–1.36) | 0.90 (0.75–1.17) | 1.04 (0.79–1.39) | .003 | 1.02 (0.79–1.38) | 1.15 (0.81–1.42) | .51 |

IQR: interquartile range.

Values in bold denote statistical significance (P<.05).

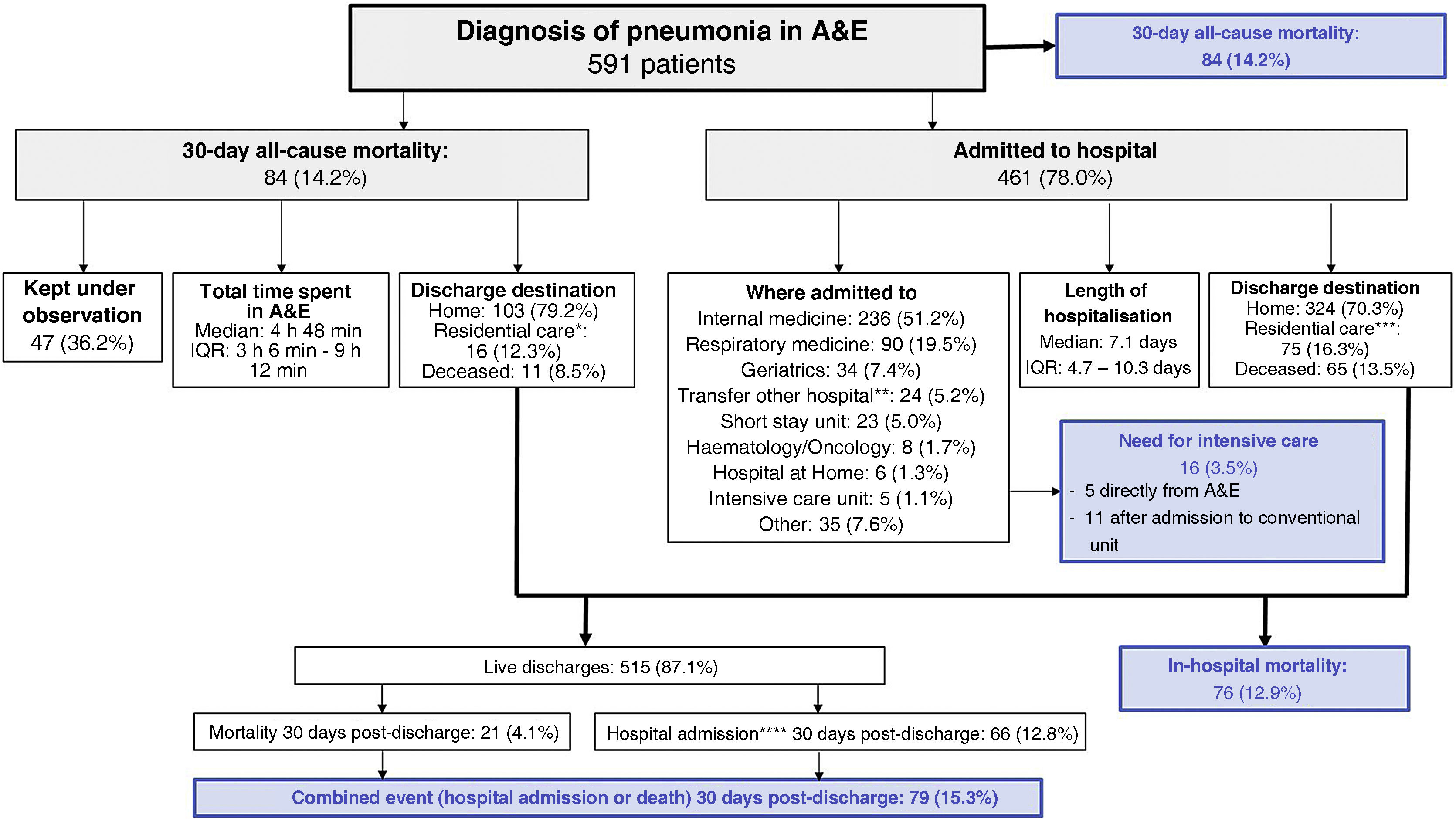

The median length of hospital stay was 7.1 days (IQR: 4.7–10.3) and the median time spent in A&E for those discharged without being admitted was 4:48h (IQR: 3:06–9:12) (Fig. 2). The overall 30-day mortality was 14.2%, while in-hospital mortality was 12.9%, and a worse prognosis was associated with functional deterioration (adjusted OR of 4.453, 95% CI: 2.361–8.400), a systolic blood pressure <100mmHg on arrival at A&E (OR 3.041; 95% CI 1.468–6.299) and having severe comorbidity (OR 2.344; 95% CI 1.363–4.030) (Table 3). These same three factors were also the most related to in-hospital mortality, although only functional impairment (OR 3.497; 95% CI 1.578–7.750) and severe comorbidity (OR 2.463; 95% CI 1.252–4.846) reached statistical significance. Some 3.5% of patients required admission to the ICU and, although the factor most strongly related to that was systolic blood pressure <100mmHg, this association did not reach statistical significance (OR 4.023; 95% CI 0.675–23.978). Lastly, the combined adverse event of death or hospitalisation at 30 days in discharged patients was observed in 15.3% of cases (4.1% and 12.8% respectively for each of these events considered individually), and was independently associated with severe comorbidity (OR 10.281; 95% CI 2.049–51.573) and functional impairment (OR 7.101; 95% CI 1.510–33.382).

Management of patients diagnosed with pneumonia in Accident and Emergency and frequency of adverse events (blue boxes) considered in the EDEN-29 study.

* The 16 patients (100%) came from residential care.

** The hospitals to which the patients were transferred were support hospitals in 10 patients (41.7%), hospitals with which the patient was linked by another process in six patients (25%), medium-stay or palliative care hospitals in five patients (20.8%) and transfer due to sectorisation in three cases (12.5%).

*** Fifty-five of the 75 patients (73.3%) came from residential care; the remaining 20 (26.7%) came from home.

**** In 41 of the 66 patients (62.1%), hospital readmission was related to the index event (pneumonia).

Multivariate analysis that explores the independent factors associated with adverse events in patients diagnosed with pneumonia in A&E. The odds ratios are presented in descending order.

| OR | Lower limit (95% CI) | Upper limit (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality (all patients) | |||

| Functional impairment (Barthel index <100 points) | 4.453 | 2.361 | 8.400 |

| Low systolic blood pressure (<100mmHg) | 3.041 | 1.468 | 6.299 |

| Severe comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index >4 points) | 2.344 | 1.363 | 4.030 |

| Male | 1.530 | 0.902 | 2.594 |

| Very high C-reactive protein (>100mg/l) | 1.410 | 0.814 | 2.442 |

| Tachycardia on arrival in A&E (>100 bpm) | 1.341 | 0.765 | 2.349 |

| Hypoxaemia on arrival in A&E (oxygen saturation <95%) | 1.331 | 0.782 | 2.264 |

| Very high leucocytosis (>15×109/l) | 1.276 | 0.753 | 2.162 |

| Major polypharmacy (10 or more long-term drugs) | 1.100 | 0.641 | 1.888 |

| Advanced age (>80) | 0.993 | 0.571 | 1.728 |

| In-hospital mortality (all patients) | |||

| Functional impairment (Barthel index <100 points) | 3.497 | 1.578 | 7.750 |

| Severe comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index >4 points) | 2.463 | 1.252 | 4.846 |

| Low systolic blood pressure (<100mmHg) | 1.909 | 0.734 | 4.965 |

| Major polypharmacy (10 or more long-term drugs) | 1.847 | 0.933 | 3.656 |

| Hypoxaemia on arrival in A&E (oxygen saturation <95%) | 1.640 | 0.807 | 3.332 |

| Tachycardia on arrival in A&E (>100 bpm) | 1.350 | 0.671 | 2.718 |

| Very high C-reactive protein (>100mg/l) | 1.191 | 0.606 | 2.341 |

| Male | 1.010 | 0.514 | 1.987 |

| Very high leucocytosis (>15×109/l) | 0.918 | 0.452 | 1.865 |

| Advanced age (>80) | 0.909 | 0.451 | 1.833 |

| Need for intensive care (hospitalised patients) | |||

| Low systolic blood pressure (<100mmHg) | 4.023 | 0.675 | 23.978 |

| Hypoxaemia on arrival in A&E (oxygen saturation <95%) | 2.205 | 0.393 | 12.356 |

| Major polypharmacy (10 or more long-term drugs) | 2.041 | 0.441 | 9.443 |

| Severe comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index >4 points) | 1.980 | 0.385 | 10.170 |

| Very high C-reactive protein (>100mg/l) | 0.842 | 0.186 | 3.800 |

| Tachycardia on arrival in A&E (>100 bpm) | 0.675 | 0.120 | 3.807 |

| Very high leucocytosis (>15×109/l) | 0.559 | 0.097 | 3.216 |

| Advanced age (>80) | 0.441 | 0.095 | 2.038 |

| Functional impairment (Barthel index <100 points) | 0.404 | 0.075 | 2.182 |

| Male | 0.286 | 0.059 | 1.394 |

| Combined event at 30 days post discharge (discharged patients) | |||

| Severe comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index >4 points) | 10.281 | 2.049 | 51.573 |

| Functional impairment (Barthel index <100 points) | 7.101 | 1.510 | 33.382 |

| Male | 2.204 | 0.619 | 7.839 |

| Very high leucocytosis (>15×109/l) | 1.801 | 0.361 | 8.996 |

| Tachycardia on arrival in A&E (>100 bpm) | 1.362 | 0.205 | 9.048 |

| Low systolic blood pressure (<100mmHg) | 1.080 | 0.062 | 18.893 |

| Major polypharmacy (10 or more long-term drugs) | 0.817 | 0.209 | 3.201 |

| Advanced age (>80) | 0.739 | 0.165 | 3.317 |

| Hypoxaemia on arrival in A&E (oxygen saturation <95%) | 0.585 | 0.138 | 2.479 |

| Very high C-reactive protein (>100mg/l) | 0.340 | 0.082 | 1.413 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Values in bold denote statistical significance (P<.05).

When the predictive capacity of each of five biomarkers commonly used in A&E to predict these adverse events was investigated, there was only a moderate, but statistically significant, capacity for creatine to predict admission to the ICU (AUC ROC of 0.702, 95% CI: 0.536–0.869), and for leucocytes to predict adverse events after discharge from A&E (0.669, 0.540–0.798). For the rest of the comparisons, the predictive capacity was very low or null (Table 4).

Predictive capacity of the five biomarkers most commonly used in A&E for adverse events in patients diagnosed with pneumonia in A&E.

| Leucocytes AUC ROC (95% CI) | C-reactive protein AUC ROC (95% CI) | Haemoglobin AUC ROC (95% CI) | Glucose AUC ROC (95% CI) | Creatinine AUC ROC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||

| 30-day all-cause mortality | 0.556 (0.464–0.648) | 0.521 (0.434–0.608) | 0.491 (0.397–0.584) | 0.552 (0.457–0.646) | 0.553 (0.464–0.642) |

| All-cause in-hospital mortality | 0.538 (0.450–0.625) | 0.529 (0.442–0.617) | 0.477 (0.382–0.572) | 0.554 (0.456–0.652) | 0.583 (0.495–0.671) |

| Hospitalised patients | |||||

| Need for admission to intensive care | 0.444 (0.318–0.571) | 0.503 (0.256–0.750) | 0.534 (0.302–0.766) | 0.444 (0.153–0.735) | 0.702 (0.536–0.869) |

| Patients discharged from A&E | |||||

| Combined event (mortality or hospital admission) at 30 days after discharge | 0.669 (0.540–0.798) | 0.451 (0.326–0.576) | 0.584 (0.439–0.729) | 0.628 (0.499–0.757) | 0.579 (0.437–0.721) |

Values in bold denote statistical significance (P<0.05).

The first important piece of data shown by the EDEN-29 study is that two in every 100 people aged over 65 will be diagnosed each year with pneumonia in an A&E in Spain. These figures were calculated from the data obtained over a week in April, considering them to be constant throughout the year, and the incidence is therefore similar to that in other studies, which report approximately 25–44 cases of pneumonia in older adults per 1000 population.8 In another study that included patients with outpatient treatment and those who required hospital admission, a classification was made into two groups depending on age; patients aged 65–69 had an incidence of 18.2 cases per 1000 population, while those over 85 had 52.3 cases per 1000 population.9 Similarly, another study found an incidence of community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospital admission in people over 65 of 18.3 cases per 1000 population. The incidence increased more than five times with age, from 8.4 cases per 1000 in patients aged 65–69 to 48.5 per 1000 in the over 90s.10 Risk factors for suffering from pneumonia include previous comorbidity (heart disease, respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, dementia, stroke), advanced age, smoking, functional impairment, immunosuppressive treatment and institutionalisation.11

The second important factor is that pneumonia is mostly diagnosed correctly in A&E. Only 3.5% of all patients hospitalised for diagnoses in A&E other than pneumonia ended up being diagnosed as pneumonia, and it is possible that in many of these cases it was a nosocomial infection.12 In a large worldwide multicentre study, half of the patients had infection, with 65% being of respiratory origin.13 Nosocomial and ventilator-associated pneumonia accounted for 22% of all hospital infections in a prevalence study carried out in 183 hospitals in the USA.14 However, it is not possible to rule out that a certain percentage of pneumonia diagnoses during a patient's stay in hospital may correspond to an error in the interpretation of the chest x-ray, as it is well known that the sensitivity of chest x-rays ranges from 38% to 76%.15 This same difficulty in the radiographic interpretation of segmental or subsegmental pneumonia may have been responsible for the fact that in one out of every eight patients diagnosed with pneumonia in A&E, this judgement was not included in the final hospital discharge report and that, in many cases, the discharge diagnoses were exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), infected bronchiectasis and pneumonitis.

The mortality rate associated with the diagnosis of pneumonia in our study was high: 12.9% in-hospital and 14.2% at 30 days. In other series, mortality rates range from 10% to 30% in the over-65s.16 Kaplan et al reported a mortality rate of 12% in patients hospitalised for pneumonia and of more than 40% at one year.17 Kothe et al confirmed these data, demonstrating that age in itself is associated with an increase in mortality rates.16 Other factors, in addition to age, related to poor prognosis are institutionalisation, dependency and previous comorbidity, as well as the complexity of the respiratory infection (22.5% mortality in complex cases vs 7.1% in patients with good recovery) and acute organ dysfunction (23.2% in patients with any organ failure vs 9.9% in cases with no dysfunction).11

Among those admitted to hospital in our study, the need for ICU was low (3.5%). This could be due to the patients' baseline situation and cognitive or functional deterioration, which made the application of invasive measures inadvisable. After reviewing previous studies, series stand out with rates of patients with pneumonia admitted to the ICU of up to 30%, in which an improvement was found in 30-day mortality associated with said admission.18 In another study, in which 23% were admitted to ICU, with a mortality rate in this subgroup of 45%, advanced age, being male, repeated infections, multi-resistance to antibiotics, complications deriving from the pneumonia, and a higher score in severity indices such as SMART-COP and CURB-65 were all defined as poor prognostic factors.19

After the patient was discharged, adverse events in the following 30 days occurred in 15.3% of cases. Bruns et al found that long-term mortality rates in convalescent patients after admission for pneumonia was three times higher than that of the general population, with the causes of death being related to the patient's previous comorbidity, including malignancy (27%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (19%) and cardiovascular disease (16%).20 In line with these results, other authors describe age, comorbidity, severity of the process and cardiovascular events as risk factors for long-term mortality after an episode of pneumonia.21

Lastly, the biomarkers analysed did not show a good ability to predict events, and only leucocytes and creatinine exhibited some potential utility. However, they should be factors to consider when deciding whether or not to discharge from A&E. Leucocytes could be one of the parameters to be assessed before directly discharging a patient with pneumonia from A&E, which occurs in around a quarter of cases, as it may indicate a greater risk of re-consultation in A&E after discharge, perhaps due to a greater inflammatory response in patients with leucocytosis. One of the most universally accepted inflammatory response biomarkers is CRP, which did not show an association with adverse outcomes in this study. However, various studies show contradictory results regarding its usefulness in identifying high-risk pneumonia. Chalmers et al.22 showed that high levels of CRP on admission and after three to four days were related to an increased risk of complications and short-term mortality in patients with pneumonia. In contrast, however, in another publication the increase in CRP did not predict the development of cardiovascular events in the short or long term.23 In another recent study,24 no relationship was found between CRP levels at admission and mortality one year after admission, although there was a relationship between increased CRP values (22mg/l) at discharge or less than 67% reduction in levels with respect to CRP at admission. This biomarker has limitations due to its slow kinetics and delay in clearance after resolution of the clinical condition. In addition, it offers lower diagnostic capacity for bacterial community-acquired pneumonia and prognosis (prediction of bacteraemia and mortality) than procalcitonin (PCT) or mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MRproADM). Its values depend on age, gender and race, so serum concentrations would have to be adjusted and interpreted in each patient.25 In short, A&E departments should have better tools, such as PCT, which provides information on the diagnosis, prognosis or therapeutic response,26 or MRproADM, whose high levels anticipate the patient's clinical deterioration and provide important information for deciding whether to admit or discharge the patient.27 Finally, we must emphasise that this study did not assess the utility of combining various biomarkers to predict adverse events, as this was not its objective. Other studies have clearly indicated that this combination of biomarkers, alone or in combination with clinical data, is useful for stratifying patient risk and helping decision-making in A&E.25

LimitationsFirstly, the 52 A&E departments which contributed patients to the EDEN registry were not chosen at random, but were eager to participate. However, the broad representation, both territorially and type-wise (university, high-tech and regional hospitals), means that the bias in this respect is likely to be small. A second limitation is that the analysis presented here was not carried out by aetiological groups, but on an overall basis. This may mean that the findings are determined by certain specific conditions, which are not analysed. All in all, we believe that with this approach the EDEN-29 study provides an overview of routine clinical practice in Spanish A&E departments. Thirdly, this manuscript involves a secondary analysis of a multipurpose cohort, so the associations presented may be influenced by factors not addressed in the cohort design. Fourthly, the results for the current status may have been affected by the individual dynamics of each hospital (especially with regard to the admission or discharge of patients) and may also have been influenced by the time of year in which the study was carried out (first week of April). Pneumonia has a seasonal pattern and the time of year analysed in this study is still under the conditions imposed by the usual flu and viral pandemics of winter and early spring. Therefore, there could be variations, especially in the incidence, when analysing other periods of the year. Fifth, the inclusion of patients in the EDEN cohort was carried out by episodes rather than by patients, so it is possible that in some cases, more than one episode could correspond to the same patient, although unlikely since the inclusion period was very short (seven days). Last of all, although in this study of older patients dependency and comorbidity were specifically considered, frailty was only evaluated tangentially through the existence of falls in the previous six months, and it is well known that frailty is an element with a significant impact on this population which is not sufficiently estimated, especially in A&E.28–30

ConclusionThe EDEN-29 study shows that pneumonia in older patients is common in A&E. The patient's baseline situation, especially their functional impairment and comorbidity, seems to influence the development of adverse events more than other factors more dependent on the pneumonia per se. Finally, the biomarkers most commonly and widely used in A&E do not, individually, have a good predictive capacity for adverse events, and this is especially true in the case of CRP.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid: Juan González del Castillo, Cesáreo Fernández Alonso, Jorge García Lamberechts, Paula Queizán García, Andrea B. Bravo Periago, Blanca Andrea Gallardo Sánchez, Alejandro Melcon Villalibre, Sara Vargas Lobé, Laura Fernández García, Beatriz Escudero Blázquez, Estrella Serrano Molina, Julia Barrado Cuchillo, Leire Paramas López, Ana Chacón García. Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Parla: Ángel Iván Díaz Salado, Beatriz Honrado Galán, Sandra Moreno Ruiz. Hospital Santa Tecla, Tarragona: Enrique Martín Mojarro, Lidia Cuevas Jiménez. Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife: Guillermo Burillo Putze, Aarati Vaswani- Bulchand, Patricia Eiroa-Hernández. Hospital Norte Tenerife: Patricia Parra-Esquivel, Montserrat Rodríguez-Cabrera. Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia: Pascual Piñera Salmerón, José Andrés Sánchez Nicolás, Yurena Reverte Pagán, Lorena Bernabé Vera, Juan José López Pérez. Hospital Universitario del Henares, Madrid: Martín Ruiz Grinspan, Cristóbal Rodríguez Leal, Rocío Martínez Avilés, María Luisa Pérez Díaz-Guerra. Hospital Clínic, Barcelona: Òscar Mir, Sònia Jiménez, Sira Aguiló Mir, Francesc Xavier Alemany González, María Florencia Poblete Palacios, Claudia Lorena Amarilla Molinas, Ivet Gina Osorio Quispe, Sandra Cuerpo Cardeñosa. Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia: Leticia Serrano Lázaro, Javier Millán Soria, Jésica Mansilla Collado, María Bóveda García. Hospital Universitario Dr Balmis, Alicante: Pere Llorens Soriano, Adriana Gil Rodrigo, Begoña Espinosa Fernández, Mónica Veguillas Benito, Sergio Guzmán Martínez, Gema Jara Torres, María Caballero Martínez. Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona: Javier Jacob Rodríguez, Ferran Llopis, Elena Fuentes, Lidia Fuentes, Francisco Chamorro, Lara Guillén, Nieves López. Hospital de Axarquía, Málaga: Coral Suero Méndez, Lucía Zambrano Serrano, Rocío Lorenzo Álvarez, Rocío Muñoz Martos. Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga: Manuel Salido Mota, Valle Toro Gallardo, Antonio Real López, Lucía Ocaña Martínez, Esther Muñoz Soler, Mario Lozano Sánchez, Eva María Fragero Blesa. Hospital Santa Bárbara, Soria: Fahd Beddar Chaib, Rodrigo Javier Gil Hernández. Hospital Valle de los Pedroches, Pozoblanco, Córdoba: Jorge Pedraza García, Paula Pedraza Ramírez. Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba: F. Javier Montero-Pérez, Carmen Lucena Aguilera, F. de Borja Quero Espinosa, Ángela Cobos Requena, Esperanza Muñoz Triano, Inmaculada Bajo Fernández, María Calderón Caro, Sierra Bretones Baena. Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid: Esther Gargallo Garc, Leonor Andrés Berián, María Esther Martínez Larrull, Susana Gordo Remartínez, Ana Isabel Castuera Gil, Laura Martín González, Melisa San Julián Romero, Montserrat Jiménez Lucena, María Dolores Pulfer. Hospital Universitario de Burgos: María Pilar López Diez, Karla López, Ricardo Hernández Cardona, Leopoldo Sánchez Santos, Monika D’ Oliveira Millán. Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León: Marta Iglesias Vela, Rudiger Carlos Chávez Flores, Alberto Álvarez Madrigal, Albert Carbó Jordá, Enrique González Revuelta, Héctor Lago Gancedo, Miguel Moreno Martín, María Isabel Fernández. Hospital Universitario Morales Meseguer, Murcia: Rafael Antonio Pérez-Costa, María Rodríguez Romero, Esperanza Marín Arranz, Sara Barnes Parra. Hospital Francesc de Borja de Gandía, Valencia: María José Fortuny Bayarri, Elena Quesada Rodríguez, Lorena Hernández Taboas, Alicia Sara Knabe. Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganés, Madrid: Cristina Iglesias, Beatriz Valle Borrego, Julia Martínez-Ibarreta Zorita, Irene Cabrera Rodrigo, Beatriz Mañero Criado, Raquel Torres Gárate, Rebeca González. Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen Arrixaca, Murcia: Eva Quero Motto, Nuria Tomas García, Lilia Amer Al Arud, Miguel Parra Morata. Hospital Universitario Lorenzo Guirao, Cieza, Murcia: Carmen Escudero Sánchez, Belén Morales Franco, José Joaquín Giménez Belló. Hospital Universitario Dr. Josep Trueta, Girona: María Adroher Muñoz, Ester Soy Ferrer, Eduard Anton Poch Ferrer. Hospital de Mendaro, Guipuzkoa: Jeong-Uh Hong Cho. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza: Rafael Marrón, Cristina Martín Durán, Fernando López López, Alberto Guillén Bove, Violeta González Guillén, María Diamanti, Beatriz Casado Ramón, Ana Herrer Castejón. Hospital Comarcal El Escorial, Madrid: Sara Gayoso Martín. Hospital Do Salnes, Villagarcia de Arosa, Pontevedra: María Goretti Sánchez Sindín. Hospital de Barbanza, Ribeira, A Coruña: Azucena Prieto Zapico, María Esther Fernández Álvarez. Hospital del Mar, Barcelona: Isabel Cirera, Bárbara Gómez y Gómez, Carmen Petrus Rivas. Hospital Santa Creu y Sant Pau, Barcelona: Aitor Alquezar Arbé, Miguel Rizzi, Marta Blázquez Andion, Carlos Romero Carret, Sergio Pérez Baena, Laura Lozano Polo, Roser Arenos Sambro, José María Guardiola Tey, Carme Beltrán Vilagrasa. Hospital de Vic, Barcelona: Lluís Llauger. Hospital Valle del Nalón, Langreo, Asturias: Ana Murcia Olagüenaga, Celia Rodríguez Valles, Verónica Vázquez Rey. Hospital Altagracia, Manzanares, Ciudad Real: Elena Carrasco Fernández, Sara Calle Fernández. Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado de Talavera de la Reina, Toledo: Ricardo Juárez González, Mar Sousa, Laura Molina, Mónica Cañete. Hospital Universitario Vinalopó, Elche, Alicante: Esther Ruescas, María Martínez Juan, Pedro Ruiz Asensio, María José Blanco Hoffman. Hospital General Universitario de Elche: Matilde González Tejera, Ana Puche Alcaraz, Cristina Chacón García. Hospital de Móstoles, Madrid: Fátima Fernández Salgado, Eva de las Nieves Rodríguez, Gema Gómez García, Beatriz Paderne Díaz. Hospital Universitario de Salamanca: Ángel García García, Francisco Javier Diego Robledo, Manuel Ángel Palomero Martín, Jesús Ángel Sánchez Serrano. Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva: José María Santos Martín, Setefilla Borne Jerez, Asumpta Ruiz Aranda. Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo: María Teresa Maza Vera, Raquel Rodríguez Calveiro, Paz Balado Dacosta, Violeta Delgado Sardina, Emma González Nespereira, Carmen Fernández Domato, Elena Sánchez Fernández-Linares. Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia: José J. Noceda Bermejo, María Teresa Sánchez Moreno, Raquel Benavent Campos, Jacinto García Acosta, Alejandro Cortés Soler. Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid: Susana Sánchez Ramón, Inmaculada García Rupérez, Pablo González Garcinuño, Raquel Hernando Fernández, José Ramón Oliva Ramos. Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset, Valencia: Maisica López, Rigoberto del Río, María Angeles Juan Gómez, Amparo Berenguer. Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville: Esther Pérez López, María Sánchez Moreno, Teresa Pablos Carrillo, Laura Redondo Lora, Rafaela Ríos Gallardo, Claudio Bueno Monreal, Pedro Rivas del Valle, Mariano Herranz García.