To analyze the prognostic accuracy of the scores NEWS, qSOFA, GYM used in hospital emergency department (ED) in the assessment of elderly patients who consult for an infectious disease.

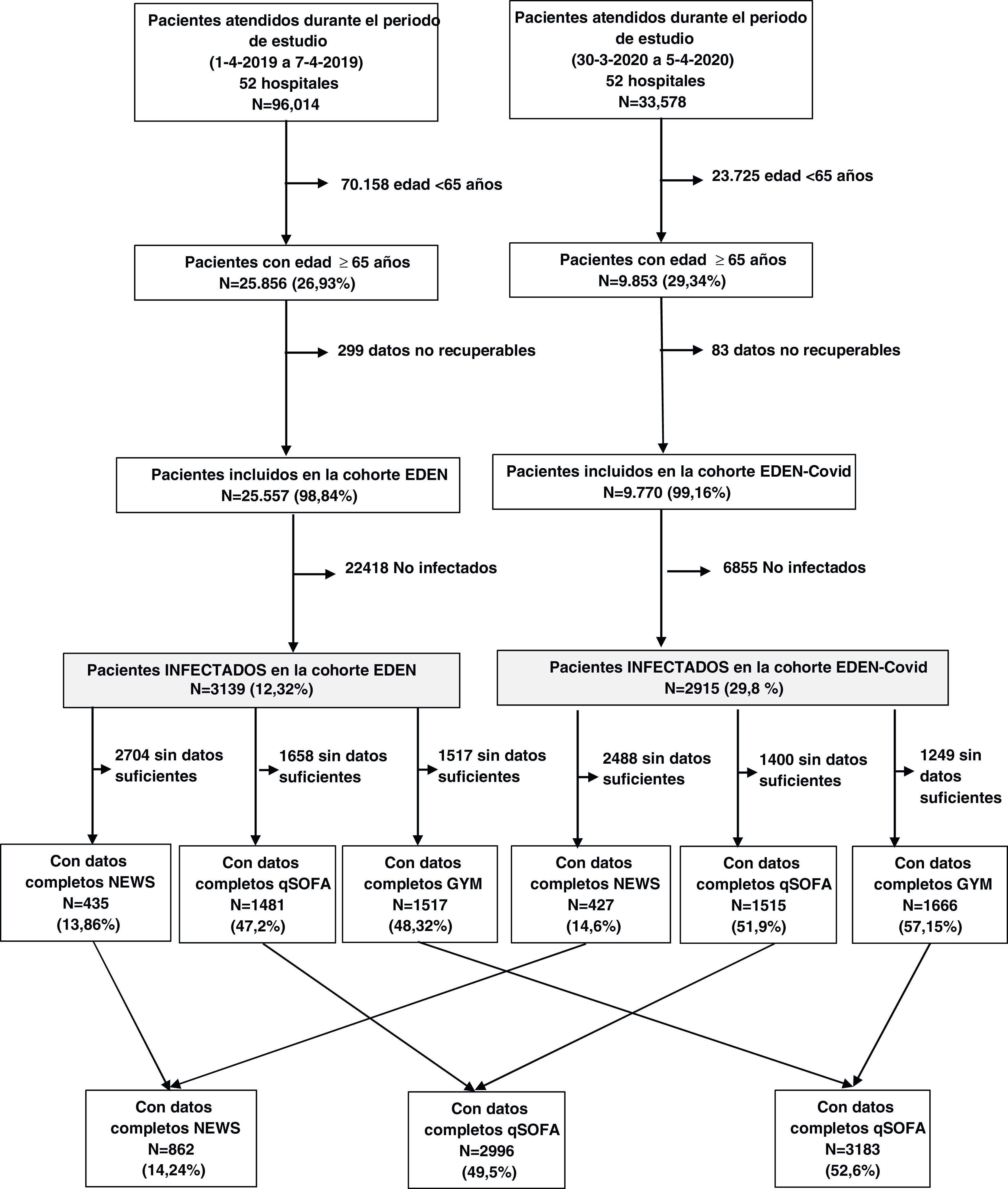

MethodsData from the EDEN (Emergency Department and Elderly Need) cohort were used. This retrospective cohort included all patients aged ≥65 years seen in 52 Spanish EDs during two weeks (from 1-4-2019 to 7-4-2019 and 30/3/2020 to 5/4/2020) with an infectious disease diagnosis in the emergency department. Demographic variables, demographic variables, comorbidities, Charlson and Barthel index and needed scores parameters were recorded. The predictive capacity for 30-day mortality of each scale was estimated by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and sensitivity and specificity were calculated for different cut-off points. The primary outcome variable was 30-day mortality.

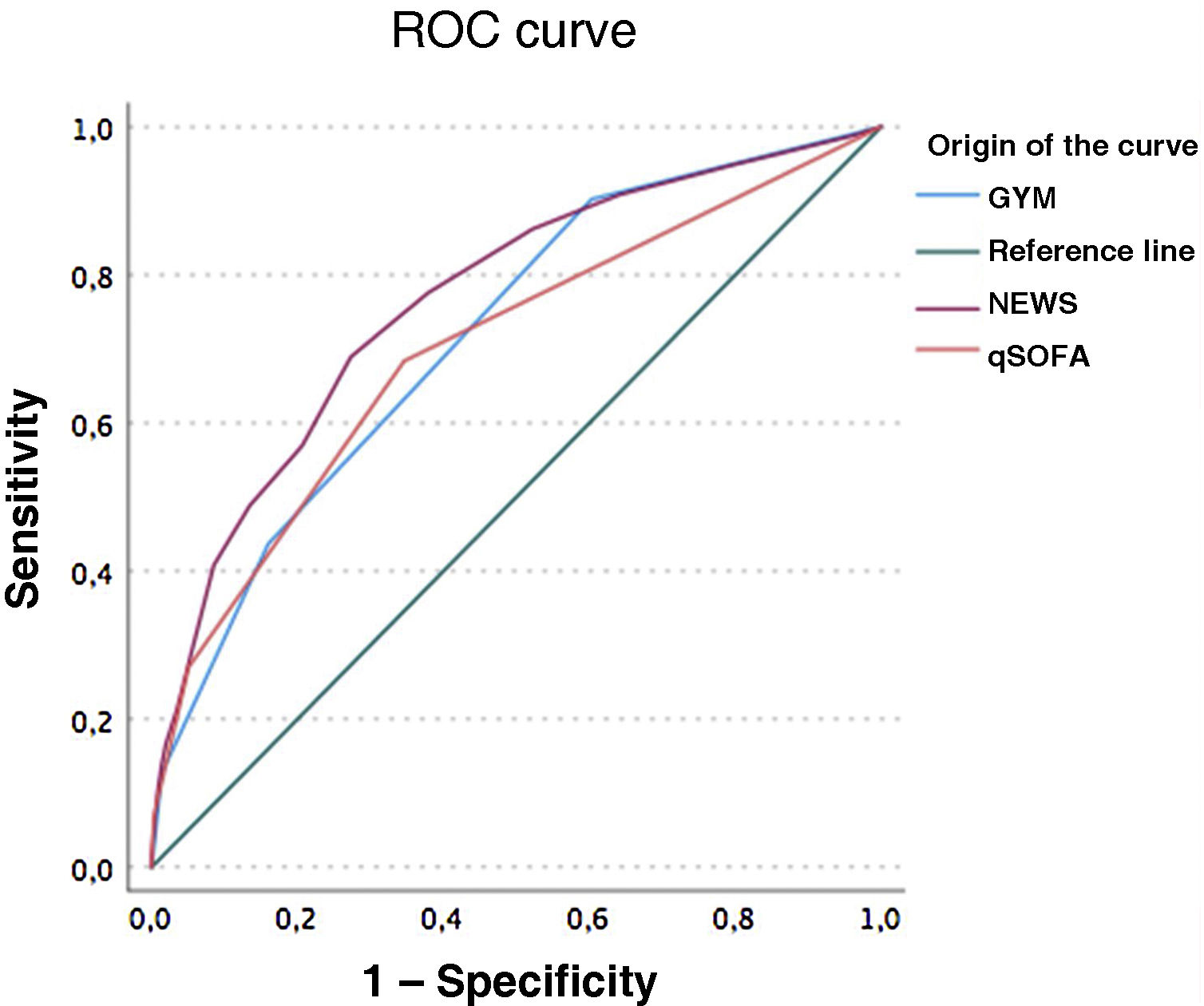

Results6054 patients were analyzed. Median age was 80 years (IQR 73–87) and 45.3% women. 993 (16,4%) patients died. NEWS score had better AUC than qSOFA (0.765, 95CI: 0.725–0.806, versus 0.700, 95%CI: 0.653–0.746; P < .001) and GYM (0.716, 95%CI: 0.675–0.758; P = .024), and there was no difference between qSOFA and GYM (P = .345). The highest sensitivity scores for 30-day mortality were GYM ≥ 1 point (85.4%) while the qSOFA score ≥2 points showed high specificity. In the case of the NEWS scale, the cut-off point ≥4 showed high sensitivity, while the cut-off point NEWS ≥ 8 showed high specificity.

ConclusionNEWS score showed the highest predictive capacity for 30-day mortality. GYM score ≥1 showed a great sensitivity, while qSOFA ≥2 scores provide the highest specificity but lower sensitivity.

Analizar la capacidad predictiva de mortalidad de las principales escalas pronósticas (NEWS, qSOFA, GYM) empleadas en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios (SUH) en pacientes ancianos que acuden por procesos infecciosos.

MétodoSe incluyeron todos los pacientes de ≥65 años que acudieron a 52 SUH españoles por un proceso infeccioso, entre el 1/4/2019 y 7/4/2019 (cohorte EDEN-Emergency Department and Elder Needs-) y entre el 30/3/2020 y 5/4/2020 (cohorte EDEN-COVID). Se consignaron variables demográficas, comorbilidad, situación funcional y datos clínicos relacionados con las escalas. Se estimó la capacidad predictiva para mortalidad a 30 días de cada escala calculando el área bajo la curva(ABC) de la característica operativa del receptor(COR), y se calcularon sensibilidad y especificidad para diferentes puntos de corte.

ResultadosSe analizaron 6054 pacientes (edad mediana:80 años; 45,3% mujeres). Fallecieron 993 pacientes(16,4%). La escala NEWS tuvo mejor ABC de las curvas COR que qSOFA (0,765, I95:0,725–0,806, versus 0,700, IC95%: 0,653–0,746; P < ,001) y que GYM (0,716, IC95%: 0,675–0,758; P = ,024), y no hubo diferencia entre qSOFA y GYM (P = ,345). En la escala GYM el punto de corte GYM ≥ 1 destacó como el más sensible, mientras que en la escala qSOFA el punto de corte ≥2 presentó una alta especificidad. La escala NEWS ≥ 4 presentó una alta sensibilidad, mientras que NEWS ≥ 8 presentó alta especificidad.

ConclusiónLa escala NEWS mostró la mayor capacidad predictiva de mortalidad a 30 días. La escala GYM con punto de corte en 1 punto o más presentó una gran sensibilidad. La escala qSOFA se caracterizó por una mayor especificidad, pero una menor sensibilidad.

For a long time the scientific community has worked hard to find the best way of estimating the prognosis of patients with infections, particularly in situations of sepsis. The first definitions of sepsis were based on the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria.1 However, the limitations of these criteria in terms of specificity and the change in the definition of sepsis in 2016, in which organ dysfunction became the cornerstone, made it necessary to analyse new screening methods.2 The quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score was introduced with the new Sepsis-3 definition.3 However, subsequent studies showed the limited sensitivity of qSOFA.4,5 This then led to the analysis of other scoring systems with better predictive capacity. They include the National Early Warning Score (NEWS), which assesses seven vital parameters to quantify the patient's clinical status.6 Since then, several studies have suggested that systems such as NEWS could be a better screening tool for the patient with sepsis.7,8 Most of these studies were conducted in relatively young patients, so their utility in identifying high-risk older adult patients may be affected by other factors associated with this age group, such as comorbidity and functional dependency, which can increase their frailty. These patients often end up attending hospital accident and emergency departments (A&E), which face the challenge of having to adapt to ensure optimal care.9,10 A study in Spain looking at patients aged over 75 found that the variables apparently associated with 30-day mortality were comorbidity, tachypnoea and altered mental state. These findings led to the GYM score (Glasgow coma scale <15, tachYpnoea, severe co-Morbidity) being defined as a tool with a good ability to predict 30-day mortality.11 A later study compared the GYM score with qSOFA and SIRS, finding better sensitivity and proposing it as an alternative for screening older adult patients with infection to predict 30-day mortality.12

Taking the above data into account, our aim with this study was to analyse the predictive capacity of the main prognostic scales (NEWS, qSOFA, GYM) used to assess patients coming to A&E with infections in older adult patients (aged ≥65).

MethodDescription of the SIESTA network and the EDEN projectThe SIESTA (Spanish Investigators in Emergency Situations TeAm) network is made up of investigators working in A&E and its main purpose is to address multidisciplinary research challenges in clinical practice related to emergency medicine from a multicentre perspective with a broad representation of Spanish A&E. The SIESTA network was established in 2020.13 Its first research challenge was the COVID-19 pandemic, in which 62 A&E participated (approximately 20% of Spanish public hospital A&E departments). The results of that challenge were published recently.14

The second project of the SIESTA research network was the EDEN challenge. The aim of EDEN was to provide comprehensive knowledge about clinical, sociodemographic, organisational, care and outcome aspects of the population aged 65 and over seen in Spanish A&E. To this end, a multipurpose registry was created which included all patients seen at the A&E of the network's member hospitals, regardless of the reason for consultation, during a pre-COVID period (1−7 April 2019, EDEN cohort) and another during the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 (30 March-5 April 2020, EDEN-COVID cohort). In the end 52 A&E participating in the study completed the inclusion of all their patients. A number of primary variables were collected for the index visit. Follow-up was carried out telematically by consulting the patient's medical records and the variables were recorded using an electronic case report form. The extended details of the project have been described previously in two published articles.15,16

EDEN-5 study designThe EDEN-5 study was specifically designed to analyse the predictive ability of the main prognostic scores used in the assessment of patients seen in A&E because of an infection. These scores included qSOFA, NEWS and GYM. We included all patients in the EDEN registry (52 participating hospitals) with the diagnosis of a suspected infection on arrival at A&E who received antibiotic treatment. We did not included patients for whom there was any explicit mention of limitation of therapeutic measures. For the analysis of the scores, only patients who had all the necessary items for calculation were analysed, the main reason for exclusion being a lack of the necessary data in the medical records for any of the items required for the calculation of these scores.

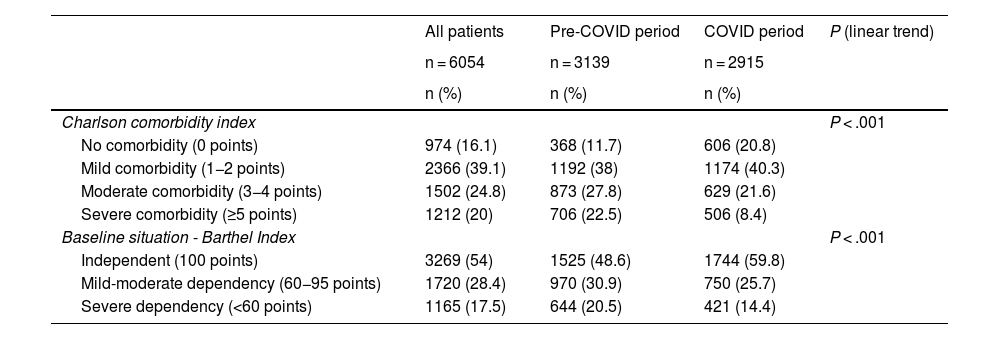

We analysed two demographic variables (age and gender), 22 previous medical conditions, the Charlson comorbidity index, classified as no comorbidity (0 points), mild (1−2 points), moderate (3−4 points) and severe comorbidity (≥5 points), and baseline functional status according to the Barthel index (BI), considering independent baseline status (BI = 100), mild-moderate dependency (BI < 100 and ≥60) and severe dependency (BI < 60). In addition, data were obtained on clinical aspects related to prognostic scales (blood pressure, level of consciousness according to the Glasgow Coma Scale, respiratory rate, temperature, O2 saturation, need for supplemental oxygen and heart rate) and the infection model was established based on the diagnoses obtained by ICD-10 coding in those cases where available. The outcome variable was 30-day all-cause mortality.

The prognostic scales were calculated according to their defining parameters.3,8,12 The cut-off values considered were those associated in the literature with poor prognosis (qSOFA ≥ 2, NEWS ≥ 5, NEWS ≥ 7, GYM ≥ 1 and GYM ≥ 2 points.6,11,12,17

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are expressed as absolute and relative values. Quantitative variables fitted to a symmetric distribution are shown with the mean and standard deviation, or with the median and interquartile range (IQR) if they do not fit such a distribution. Differences between groups were assessed using the chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test if necessary) for qualitative variables and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for quantitative variables. Associations are expressed as odds ratio (OR) with the 95% confidence interval (CI). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed for the qSOFA, NEWS and GYM scores. The areas under the curve (AUC) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) are shown for each of them and statistical differences were analysed by comparing the ROC curves using the Delong test. In addition, sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV respectively), positive and negative likelihood ratios (PLR and NLR respectively) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for the different scores for each scale. Comparison of proportions was performed with McNemar's test for qSOFA, NEWS and GYM values according to the different cut-off points. For all tests, significance was set at P < .05. All statistical processing was performed using SPSS Statistics v.26 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and STATA v14.

Ethical considerationsThe EDEN project was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid (protocol HCSC/22/005-E). The creation of the EDEN cohort and the work emanating from it has adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki at all times.

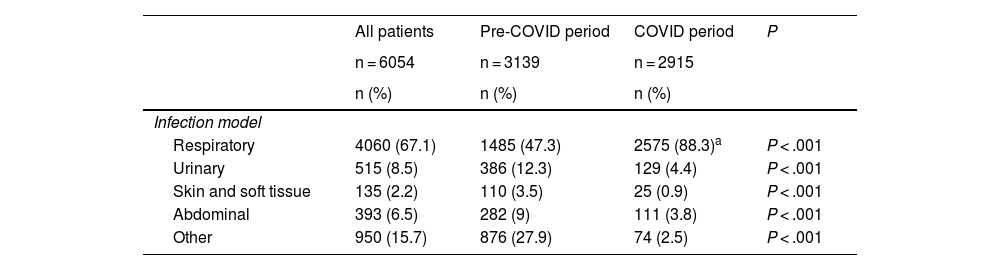

ResultsOf the 35,709 patients seen during both study periods, 6,054 (16.95%) went to A&E for an infectious condition, with 3139 (51.8%) cases corresponding to the pre-COVID period (EDEN cohort) and 2915 (48.14) to the COVID period (EDEN-COVID cohort) (Fig. 1). The median age was 80 (IQR: 73–87) and 45.3% were women, with the most common comorbidities being hypertension (73%), dyslipidaemia (51.6%), diabetes mellitus (33%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (26.6%). Moderate or severe comorbidity was observed in 44.8%, with comorbidity being significantly higher in the pre-COVID period (P for linear trend <.001). Functional dependency status was also higher in the pre-COVID period (P for linear trend <.001) (Table 1). The most common infection model in both periods was respiratory, being significantly higher in the COVID period (1,261 [47.3%] patients in pre-COVID period vs 2070 [88.3%] in the COVID period; P < .001) due to the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection (1236 [52.8%] patients) and to the detriment of the other infection models (Table 2).

Comorbidity and degree of independence in both study periods.

| All patients | Pre-COVID period | COVID period | P (linear trend) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 6054 | n = 3139 | n = 2915 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | P < .001 | |||

| No comorbidity (0 points) | 974 (16.1) | 368 (11.7) | 606 (20.8) | |

| Mild comorbidity (1−2 points) | 2366 (39.1) | 1192 (38) | 1174 (40.3) | |

| Moderate comorbidity (3−4 points) | 1502 (24.8) | 873 (27.8) | 629 (21.6) | |

| Severe comorbidity (≥5 points) | 1212 (20) | 706 (22.5) | 506 (8.4) | |

| Baseline situation - Barthel Index | P < .001 | |||

| Independent (100 points) | 3269 (54) | 1525 (48.6) | 1744 (59.8) | |

| Mild-moderate dependency (60−95 points) | 1720 (28.4) | 970 (30.9) | 750 (25.7) | |

| Severe dependency (<60 points) | 1165 (17.5) | 644 (20.5) | 421 (14.4) | |

Infection models obtained in ICD-10 diagnostic coding.

| All patients | Pre-COVID period | COVID period | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 6054 | n = 3139 | n = 2915 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Infection model | ||||

| Respiratory | 4060 (67.1) | 1485 (47.3) | 2575 (88.3)a | P < .001 |

| Urinary | 515 (8.5) | 386 (12.3) | 129 (4.4) | P < .001 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 135 (2.2) | 110 (3.5) | 25 (0.9) | P < .001 |

| Abdominal | 393 (6.5) | 282 (9) | 111 (3.8) | P < .001 |

| Other | 950 (15.7) | 876 (27.9) | 74 (2.5) | P < .001 |

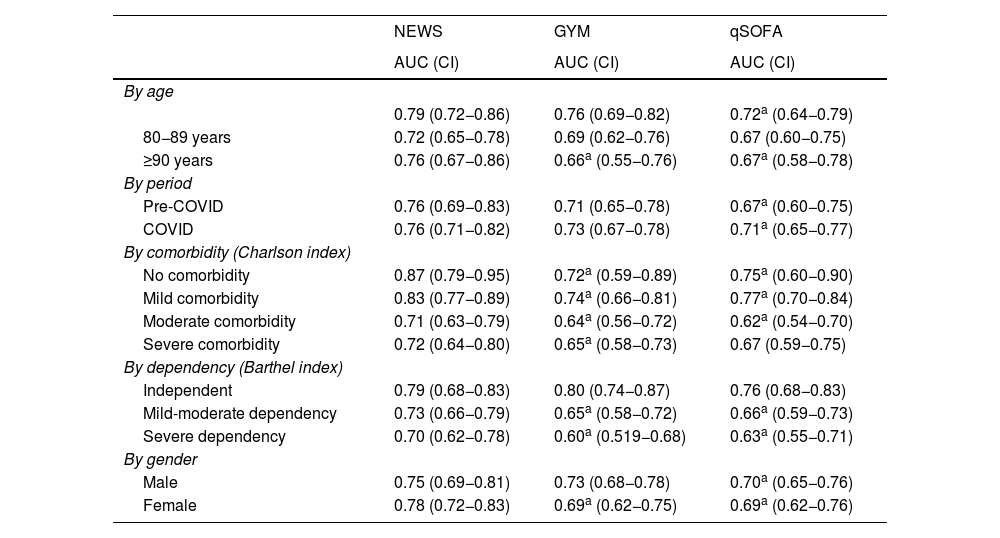

Of the total number of patients analysed, 993 (16.5%) died: 365 (11.6%) in the pre-COVID period and 628 (21.5%) in the COVID period, with these differences being statistically significant (P < .001). The overall AUC for 30-day mortality was 0.765 for NEWS (95% CI 0.725−0.806, P < .001), 0.70 for the qSOFA score (95% CI 0.653−0.746) and 0.716 for the GYM score (95% CI 0.675−0.758, P < .001). Statistical differences comparing ROC curves were: qSOFA vs NEWS, P < .001; GYM vs NEWS, P = .024; and qSOFA vs GYM, P = .345 (Fig. 2). The results of ROC curves and AUC of qSOFA, NEWS and GYM scores broken down by age, period, comorbidity, dependency and gender are shown in Table 3. It should be noted that the NEWS score has a higher AUC than GYM and qSOFA in all the breakdowns.

Result of ROC curves of NEWS, qSOFA and GYM scores.

The AUC-ROC for 30-day mortality was 0.765 (95% CI, 0.725−0.806, P < .001) for NEWS, 0.70 for the qSOFA score (95% CI, 0.653−0.746) and 0.716 for the GYM score (95% CI 0.675−0.758, P < .001). Statistical differences comparing the diagnostic performance curves (ROC) were: qSOFA vs NEWS P < .001; GYM vs NEWS P = .024; qSOFA vs GYM P = .345.

Results of ROC curves and AUC of qSOFA, NEWS and GYM by age, period, comorbidity, dependency and gender in relation to the prediction of 30-day mortality.

| NEWS | GYM | qSOFA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (CI) | AUC (CI) | AUC (CI) | |

| By age | |||

| 0.79 (0.72−0.86) | 0.76 (0.69−0.82) | 0.72a (0.64−0.79) | |

| 80−89 years | 0.72 (0.65−0.78) | 0.69 (0.62−0.76) | 0.67 (0.60−0.75) |

| ≥90 years | 0.76 (0.67−0.86) | 0.66a (0.55−0.76) | 0.67a (0.58−0.78) |

| By period | |||

| Pre-COVID | 0.76 (0.69−0.83) | 0.71 (0.65−0.78) | 0.67a (0.60−0.75) |

| COVID | 0.76 (0.71−0.82) | 0.73 (0.67−0.78) | 0.71a (0.65−0.77) |

| By comorbidity (Charlson index) | |||

| No comorbidity | 0.87 (0.79−0.95) | 0.72a (0.59−0.89) | 0.75a (0.60−0.90) |

| Mild comorbidity | 0.83 (0.77−0.89) | 0.74a (0.66−0.81) | 0.77a (0.70−0.84) |

| Moderate comorbidity | 0.71 (0.63−0.79) | 0.64a (0.56−0.72) | 0.62a (0.54−0.70) |

| Severe comorbidity | 0.72 (0.64−0.80) | 0.65a (0.58−0.73) | 0.67 (0.59−0.75) |

| By dependency (Barthel index) | |||

| Independent | 0.79 (0.68−0.83) | 0.80 (0.74−0.87) | 0.76 (0.68−0.83) |

| Mild-moderate dependency | 0.73 (0.66−0.79) | 0.65a (0.58−0.72) | 0.66a (0.59−0.73) |

| Severe dependency | 0.70 (0.62−0.78) | 0.60a (0.519−0.68) | 0.63a (0.55−0.71) |

| By gender | |||

| Male | 0.75 (0.69−0.81) | 0.73 (0.68−0.78) | 0.70a (0.65−0.76) |

| Female | 0.78 (0.72−0.83) | 0.69a (0.62−0.75) | 0.69a (0.62−0.76) |

Charlson index: no comorbidity 0 points; mild comorbidity 1−2; moderate 3−4; severe ≥5.

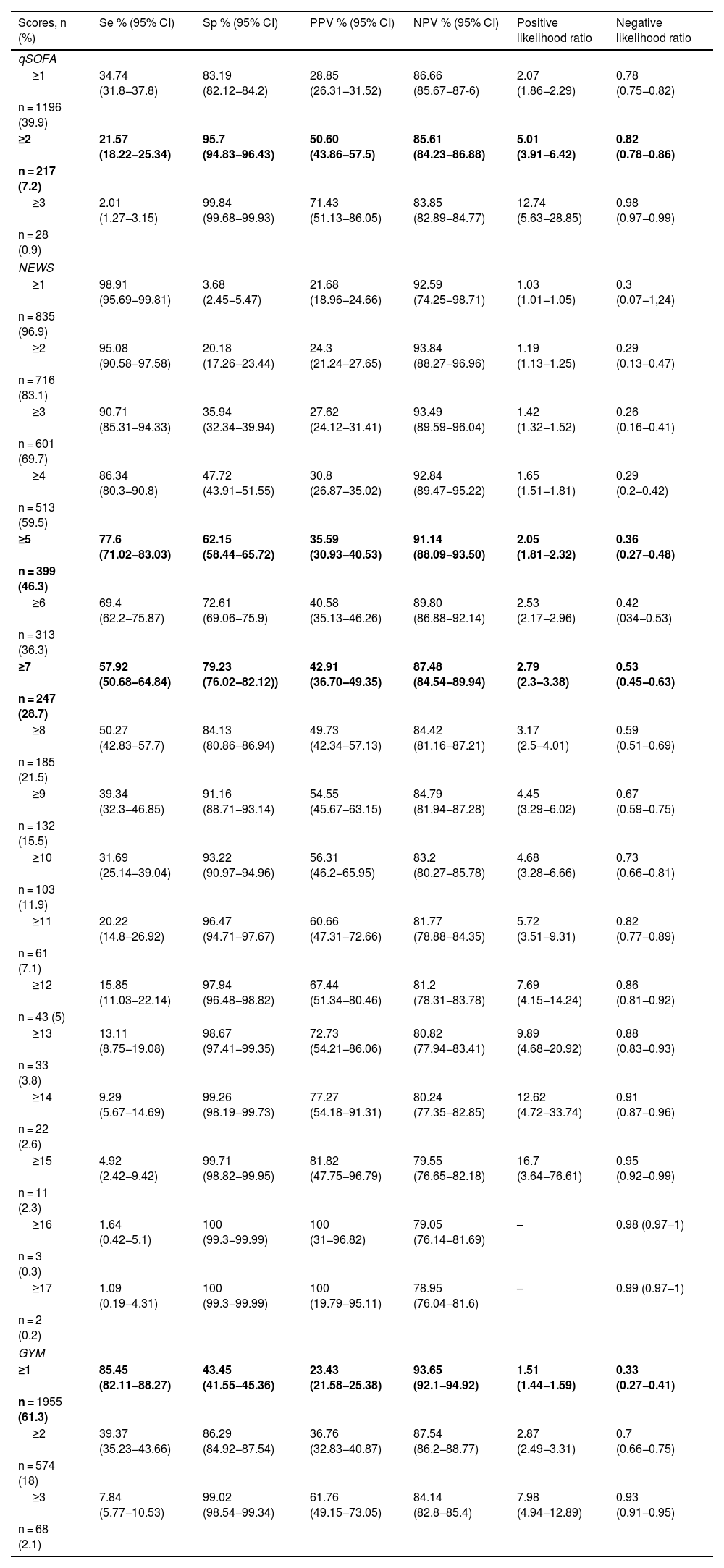

Table 4 shows the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, positive likelihood ratios (PLR) and negative likelihood ratios (NLR) for each of the cut-off points for the three scores. In the GYM score the cut-off point ≥1 stood out as the most sensitive, with NLR of 0.33, while in the qSOFA score the cut-off point ≥2 showed a high specificity with PLR > 3. In the case of the NEWS score, the cut-off point ≥4 showed a high sensitivity, with NLR < 0.3, while the cut-off point ≥8 showed a high specificity, with PLR > 3.

Predictive ability for 30-day mortality of the different qSOFA, NEWS and GYM scores according to different cut-off points.

| Scores, n (%) | Se % (95% CI) | Sp % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio | Negative likelihood ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qSOFA | ||||||

| ≥1 | 34.74 (31.8−37.8) | 83.19 (82.12−84.2) | 28.85 (26.31−31.52) | 86.66 (85.67−87-6) | 2.07 (1.86−2.29) | 0.78 (0.75−0.82) |

| n = 1196 (39.9) | ||||||

| ≥2 | 21.57 (18.22−25.34) | 95.7 (94.83−96.43) | 50.60 (43.86−57.5) | 85.61 (84.23−86.88) | 5.01 (3.91−6.42) | 0.82 (0.78−0.86) |

| n = 217 (7.2) | ||||||

| ≥3 | 2.01 (1.27−3.15) | 99.84 (99.68−99.93) | 71.43 (51.13−86.05) | 83.85 (82.89−84.77) | 12.74 (5.63−28.85) | 0.98 (0.97−0.99) |

| n = 28 (0.9) | ||||||

| NEWS | ||||||

| ≥1 | 98.91 (95.69−99.81) | 3.68 (2.45−5.47) | 21.68 (18.96−24.66) | 92.59 (74.25−98.71) | 1.03 (1.01−1.05) | 0.3 (0.07−1,24) |

| n = 835 (96.9) | ||||||

| ≥2 | 95.08 (90.58−97.58) | 20.18 (17.26−23.44) | 24.3 (21.24−27.65) | 93.84 (88.27−96.96) | 1.19 (1.13−1.25) | 0.29 (0.13−0.47) |

| n = 716 (83.1) | ||||||

| ≥3 | 90.71 (85.31−94.33) | 35.94 (32.34−39.94) | 27.62 (24.12−31.41) | 93.49 (89.59−96.04) | 1.42 (1.32−1.52) | 0.26 (0.16−0.41) |

| n = 601 (69.7) | ||||||

| ≥4 | 86.34 (80.3−90.8) | 47.72 (43.91−51.55) | 30.8 (26.87−35.02) | 92.84 (89.47−95.22) | 1.65 (1.51−1.81) | 0.29 (0.2−0.42) |

| n = 513 (59.5) | ||||||

| ≥5 | 77.6 (71.02−83.03) | 62.15 (58.44−65.72) | 35.59 (30.93−40.53) | 91.14 (88.09−93.50) | 2.05 (1.81−2.32) | 0.36 (0.27−0.48) |

| n = 399 (46.3) | ||||||

| ≥6 | 69.4 (62.2−75.87) | 72.61 (69.06−75.9) | 40.58 (35.13−46.26) | 89.80 (86.88−92.14) | 2.53 (2.17−2.96) | 0.42 (034−0.53) |

| n = 313 (36.3) | ||||||

| ≥7 | 57.92 (50.68−64.84) | 79.23 (76.02−82.12)) | 42.91 (36.70−49.35) | 87.48 (84.54−89.94) | 2.79 (2.3−3.38) | 0.53 (0.45−0.63) |

| n = 247 (28.7) | ||||||

| ≥8 | 50.27 (42.83−57.7) | 84.13 (80.86−86.94) | 49.73 (42.34−57.13) | 84.42 (81.16−87.21) | 3.17 (2.5−4.01) | 0.59 (0.51−0.69) |

| n = 185 (21.5) | ||||||

| ≥9 | 39.34 (32.3−46.85) | 91.16 (88.71−93.14) | 54.55 (45.67−63.15) | 84.79 (81.94−87.28) | 4.45 (3.29−6.02) | 0.67 (0.59−0.75) |

| n = 132 (15.5) | ||||||

| ≥10 | 31.69 (25.14−39.04) | 93.22 (90.97−94.96) | 56.31 (46.2−65.95) | 83.2 (80.27−85.78) | 4.68 (3.28−6.66) | 0.73 (0.66−0.81) |

| n = 103 (11.9) | ||||||

| ≥11 | 20.22 (14.8−26.92) | 96.47 (94.71−97.67) | 60.66 (47.31−72.66) | 81.77 (78.88−84.35) | 5.72 (3.51−9.31) | 0.82 (0.77−0.89) |

| n = 61 (7.1) | ||||||

| ≥12 | 15.85 (11.03−22.14) | 97.94 (96.48−98.82) | 67.44 (51.34−80.46) | 81.2 (78.31−83.78) | 7.69 (4.15−14.24) | 0.86 (0.81−0.92) |

| n = 43 (5) | ||||||

| ≥13 | 13.11 (8.75−19.08) | 98.67 (97.41−99.35) | 72.73 (54.21−86.06) | 80.82 (77.94−83.41) | 9.89 (4.68−20.92) | 0.88 (0.83−0.93) |

| n = 33 (3.8) | ||||||

| ≥14 | 9.29 (5.67−14.69) | 99.26 (98.19−99.73) | 77.27 (54.18−91.31) | 80.24 (77.35−82.85) | 12.62 (4.72−33.74) | 0.91 (0.87−0.96) |

| n = 22 (2.6) | ||||||

| ≥15 | 4.92 (2.42−9.42) | 99.71 (98.82−99.95) | 81.82 (47.75−96.79) | 79.55 (76.65−82.18) | 16.7 (3.64−76.61) | 0.95 (0.92−0.99) |

| n = 11 (2.3) | ||||||

| ≥16 | 1.64 (0.42−5.1) | 100 (99.3−99.99) | 100 (31−96.82) | 79.05 (76.14−81.69) | – | 0.98 (0.97−1) |

| n = 3 (0.3) | ||||||

| ≥17 | 1.09 (0.19−4.31) | 100 (99.3−99.99) | 100 (19.79−95.11) | 78.95 (76.04−81.6) | – | 0.99 (0.97−1) |

| n = 2 (0.2) | ||||||

| GYM | ||||||

| ≥1 | 85.45 (82.11−88.27) | 43.45 (41.55−45.36) | 23.43 (21.58−25.38) | 93.65 (92.1−94.92) | 1.51 (1.44−1.59) | 0.33 (0.27−0.41) |

| n = 1955 (61.3) | ||||||

| ≥2 | 39.37 (35.23−43.66) | 86.29 (84.92−87.54) | 36.76 (32.83−40.87) | 87.54 (86.2−88.77) | 2.87 (2.49−3.31) | 0.7 (0.66−0.75) |

| n = 574 (18) | ||||||

| ≥3 | 7.84 (5.77−10.53) | 99.02 (98.54−99.34) | 61.76 (49.15−73.05) | 84.14 (82.8−85.4) | 7.98 (4.94−12.89) | 0.93 (0.91−0.95) |

| n = 68 (2.1) | ||||||

Sp: specificity; Se: sensitivity; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

The cut-off points used in the literature as the main cut-off points are in bold.

This study compares the main prognostic scores used in the early detection of patients with severe infection applied to the subgroup of older adult patients. In our study, the NEWS had the best predictive ability for mortality overall compared to the GYM and qSOFA scores. Several studies comparing qSOFA and NEWS have been published in recent years with similar results, although generally conducted in a younger population.17,18 Churpek et al.19 compared the NEWS to the qSOFA and SIRS scores outside the intensive care unit setting, obtaining an AUC similar to that of our study, although their study was carried out in patients with a mean age of around 58 and included not only patients assessed in A&E but also on hospital wards. Similarly, Usman et al.20 compared NEWS versus qSOFA and SIRS in younger patients in A&E, with NEWS having better predictive ability (AUC: 0.91) for the detection of sepsis or septic shock (S/SS). In our study, however, we did not analyse the likelihood of S/SS, the outcome variable studied being 30-day mortality. Arévalo-Buitrago et al.21 recently published a study carried out in Spain in which they analysed the capacity of a variant of this scale (NEWS-2) as a predictor of hospital admission and the occurrence of adverse events (AE) from A&E triage in patients from the general population attending A&E, demonstrating an excellent predictive capacity for admission to the ICU, mortality and hospital admission. Nonetheless, most of the published studies were conducted in a population younger than that in our study. González del Castillo et al.11 published a study analysing factors associated with mortality in older adult patients, proposing the GYM scale as an alternative to SIRS for predicting mortality. Similarly, a later study compared this scale with qSOFA, showing an AUC of 0.73 versus 0.69 respectively.12 These results are similar to those obtained in our study, in which, although the GYM scale had a slightly higher AUC, the differences compared to qSOFA were not statistically significant. We were unable to find any published studies comparing the GYM score and the NEWS for prognosis in patients of any age. In the EDEN-5 study, the NEWS had greater predictive ability for mortality than the GYM score. This is only to be expected, as the GYM and qSOFA scores share two of their three items, which involve parameters that often represent symptoms of late organ failure, such as altered mental state. Although the GYM score had a higher AUC than the qSOFA, these differences were not statistically significant. In our study, we analysed the AUC according to age, study period, comorbidity, functional status and gender, finding that in all cases, the NEWS showed the best predictive ability for mortality; there were no significant differences between the GYM and qSOFA scores. We can therefore state that in our study, the NEWS had good predictive ability regardless of aspects such as age, gender, degree of functional dependency or comorbidity.

In relation to the sensitivity of the scores studied, the GYM score with the cut-off point at 1 point was one of the most sensitive, along with the NEWS, using 4 points as the cut-off point. The qSOFA score, however, had the lowest sensitivity at any of its cut-off points. These results are similar to the study by González del Castillo et al.,12 where the GYM score was proposed as a good screening method in older adults by virtue of its higher sensitivity. The low sensitivity of qSOFA for predicting death has been confirmed in different studies.4,19,20,22 This has led some authors not to recommend the use of the qSOFA as the sole screening method for sepsis.23 In their meta-analysis, Serafim et al.4 compared the predictive ability of qSOFA to that of SIRS, finding that qSOFA was less sensitive in detecting sepsis, but more predictive of in-hospital mortality, especially based on its high specificity. However, they did not compare other scales used in our study. A meta-analysis and systematic review by Fernando et al.22 analysed the sensitivity and specificity of qSOFA, and specifically for A&E patients, these values were 46% and 81% respectively. However, the authors made no distinction with regard to the age of the patients. In our study, the sensitivity of qSOFA was lower, but it was similar to studies in older patients.12

The literature shows that the NEWS has been widely used with cut-off points at 5 and 7 points. This aspect has been analysed in several studies, where the authors have noted the high sensitivity of the cut-off point ≥5points (Se: 87%–89%, Sp: 40%–42%) as well as its excellent negative predictive value.17,18 For that reason, some authors have suggested recommending the use of the NEWS scale as a screening test for the detection of sepsis in A&E from the first point of care at triage.20 Furthermore, our results are in line with the recommendation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) 2021 guidelines, which argue against the use of qSOFA, compared to SIRS, NEWS or Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), as the only screening tool for the detection of sepsis or septic shock.23 In the EDEN-5 study, the NEWS with a cut-off of ≥5 points showed good sensitivity, with higher specificity than the GYM score ≥1. However, we found ≥4and ≥8points respectively to be optimal cut-off points for NEWS. These cut-off points have also been referred to in the study by Usman et al.,20 where they compared SIRS, qSOFA and NEWS for early identification of sepsis in A&E. The authors also suggested that NEWS could offer greater scoring flexibility in relation to SIRS and qSOFA, by allowing the creation of multiple severity categories from low and moderate to high risk, suggesting the determination of lactate in moderate risk cases and an early diagnosis and treatment strategy in those at high risk.

With regard to specificity, the qSOFA score had the highest in the EDEN-5 study. These data are similar to previous published studies, in which the qSOFA had high specificity.4,17–20,22 At the same time, the utility of the GYM score has been indicated primarily on the basis of its high sensitivity with 1 as the cut-off point.12 However, in our study, we found a high specificity when the cut-off point was at 2, although it was still somewhat lower than that of the qSOFA score. The NEWS showed higher specificity with the cut-off at ≥8 points. This has also been reported in publications such as that of Liu et al.,24 which highlighted the high specificity of the NEWS, with even a better sensitivity profile, using a cut-off point of ≥8 points.

Lastly, we consider that all three scores are based on parameters which are accessible and easily measurable from the patient's bedside or at triage, making them applicable from the patient's first point of care, this being particularly useful for A&E or even out-of-hospital care. The most sensitive scores of these systems, such as GYM ≥ 1 or NEWS ≥ 4 points, make it possible to detect patients with the worst prognosis at an early stage, allowing the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures to be initiated in order to improve the patient's chances of survival. This could include activation of the sepsis code from both in-hospital and out-of-hospital settings, coordinated with the services involved in sepsis protocols. Although in our study we did not analyse the predictive capacity of these scores in relation to the likelihood of sepsis, we believe that their ability to predict death provides adequate screening to select cases in which early therapeutic measures should be initiated, and which may subsequently be categorised as sepsis once all the necessary diagnostic results are obtained.

LimitationsThis study has a number of limitations. Firstly, the 52 A&E departments which contributed patients to the EDEN registry were not chosen at random, but were eager to participate. However, the broad representation, both territorially (14 of Spain's 17 autonomous regions were represented) and in type-wise (university, high-tech and regional hospitals), means that the bias in this respect is likely to be small. Secondly, the analysis presented here was not carried out by disease groups, but on an overall basis. This may mean that the findings are determined by certain specific conditions, which are not analysed in this paper. Thirdly, there could be some reporting bias due to the high number of people involved in the data collection. However, all investigators involved in data collection had received prior training, and all data were verified by a principal investigator from each site. The different criteria, definitions and parameters were previously defined by the EDEN challenge's scientific committee and were agreed on by the investigators. In fourth place, this manuscript involves a secondary analysis of a multipurpose cohort, so the associations presented may be influenced by factors not addressed in the cohort design. The findings should therefore be seen as hypothesis-generating and should be confirmed by studies specifically designed for this purpose. In fifth place, given the retrospective design of the study, cases and information may have been lost in the different episodes when compiling the data in the medical records. A lack of necessary data in some items required for the calculation of these scores meant the exclusion of patients due to insufficient data. However, in order to avoid bias, the parameters inherent to the three prognostic scales were calculated exclusively in those who had all parameters collected. Last of all, the patients included in this study were those clinically suspected of having an infection by the Accident and Emergency physician, so microbiological confirmation of infection was not obtained. Although the lack of verification of the final diagnosis may represent a bias of the study, we felt that this approach based on the diagnosis of suspicion was more like real life and the decisions made during the initial assessment of patients in A&E.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the NEWS showed the highest predictive capacity for 30-day mortality with respect to the qSOFA and GYM scores, with the optimal cut-off for specificity at 8 points and at 4 points for sensitivity. The GYM scale with a cut-off point of 1 or more showed a high sensitivity, making it a good screening tool in the older adult patient with infection. The qSOFA scale was characterised by a higher specificity but lower sensitivity, which a priori would rule out the use of this scale as an initial screening tool in the older adult patient with infection.

FundingThis work was carried out without any direct or indirect financial support.

Author contributionsAll authors discussed the idea and design of the study and provided patients. The data analysis and writing of the first draft were carried out by EJGL, OM and JGC. All authors read this draft and provided feedback for the final version. EJGL is the guarantor of the document, taking responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to publication.

Conflicts of interestAll the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest directly or indirectly related to this manuscript.

Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid: Juan González del Castillo, Cesáreo Fernández Alonso, Eric Jorge García Lamberechts, Sara Vargas Lobé, Laura Fernández García, Beatriz Escudero Blázquez, Estrella Serrano Molina, Julia Barrado Cuchillo, Leire Paramas López, Ana Chacón García.

Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Parla: Diana Rosendo Mesino, Ángel Iván Diaz Salado, Alicia Fuente Gaforio, Cristina Güemes de la Iglesia.

Hospital Santa Tecla, Tarragona: Sílvia Flores Quesada, Lidia Cuevas Jiménez, Osvaldo Jorge Troiano Ungerer.

Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife: Guillermo Burillo Putze, Aarati Vaswani-Bulchand, Patricia Eiroa-Hernández.

Hospital Norte Tenerife: Montserrat Rodríguez-Cabrera, Patricia Parra-Esquivel.

Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia: Pascual Piñera Salmerón, Elena Sánchez García, Eduardo Alarcón Capel, Ana María Albaladejo Rubio, Juan Javier García Fernández, Paula Lázaro Aragüés.

Hospital Universitario del Henares, Madrid: Raquel Barrós González, Gema Domínguez Gioya, María Adalid Moll, Patricia Gantes Nieto.

Hospital Clínic, Barcelona: Òscar Miró, Sònia Jiménez, Sira Aguiló Mir, Francesc Xavier Alemany González, María Florencia Poblete Palacios, Claudia Lorena Amarilla Molinas, Ivet Gina Osorio Quispe, Sandra Cuerpo Cardeñosa.

Hospital General Universitario de Elche: Matilde González Tejera, Ana Puche Alcaraz, Cristina Chacón García.

Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia: Leticia Serrano Lázaro, Javier Millán Soria, Jésica Mansilla Collado, María Bóveda García.

Hospital Universitario Dr. Balmis, Alicante: Pere Llorens Soriano, Adriana Gil Rodrigo, Begoña Espinosa Fernández, Mónica Veguillas Benito, Sergio Guzmán Martínez, Gema Jara Torres, María Caballero Martínez.

Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, l'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona: Javier Jacob Rodríguez, Ferran Llopis, Elena Fuentes, Lidia Fuentes, Francisco Chamorro, Lara Guillen, Nieves López.

Hospital de Axarquía, Málaga: Coral Suero Méndez, Rocío Muñoz Martos, Rocío Lorenzo Álvarez, Lucía Zambrano Serrano.

Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga: Manuel Salido Mota, Valle Toro Gallardo, Antonio Real López, Lucía Ocaña Martínez, Esther Muñoz Soler, Mario Lozano Sánchez, Eva Fraguero Blesa.

Hospital Santa Bárbara, Soria: Fahd Beddar Chaib, Rodrigo Javier Gil Hernández.

Hospital Valle de los Pedroches, Pozoblanco, Córdoba: Jorge Pedraza García, Paula Pedraza Ramírez.

Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba: Francisco Javier Montero-Pérez, Carmen Lucena Aguilera, Francisco de Borja Quero Espinosa, Ángela Cobos Requena, Esperanza Muñoz Triano, Inmaculada Bajo Fernández, María Calderón Caro, Sierra Bretones Baena.

Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid: Melisa San Julián Romero, Montserrat Jiménez Lucena, María Dolores Pulfer, Juan Fernández Herranz, Marta Rincón Francés, Irene Arnaiz Fernández, Esther Gargallo Garcia, Juan Antonio Andueza Lillo.

Hospital Universitario de Burgos: Leopoldo Sánchez Santos, Monika d’Oliveira Millán, Amanda Ibisate Cubillas, Monica de Diego Arnaiz, Verónica Castro Jiménez.

Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León [León University Healthcare Complex]: Mónica Santos Orús, Rudiger Carlos Chávez Flores, Alberto Álvarez Madrigal, Albert Carbó Jordá, Enrique González Revuelta, Héctor Lago Gancedo, Miguel Moreno Martín.

Hospital Universitario Morales Meseguer, Murcia: Rafael Antonio Pérez-Costa, María Rodríguez Romero, Esperanza Marín Arranz, Ana Barnes Parra.

Hospital Francesc de Borja, Gandía, Valencia: Miriam Gamir Roselló, Sonia Cascant Pérez, Alessandro Evangelista, Anna Ferrús Ferrús.

Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganés, Madrid: Esther Álvarez-Rodríguez, Guillermo Villoria Almeida, María José Hernández Martínez, Ana Benito Blanco, Vanesa Abad Cuñado.

Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia: Laura Bernal Martínez, Marina Carrión Fernández, Lilia Amer al Arud, Miguel Parra Morata.

Hospital Universitario Lorenzo Guirao, Cieza, Murcia: Belén Morales Franco, Alberto Artieda Larrañaga.

Hospital Universitario Dr. Josep Trueta, Girona: Maria Adroher Muñoz, Ester Soy Ferrer, Eduard Anton Poch Ferrer.

Hospital de Mendaro, Guipuzkoa: Jeong-Uh Hong Cho.

Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza: Cristina Martín Durán, María Teresa Escolar Martínez-Berganza, Iciar González Salvatierra, Alberto Guillén Bobé, Violeta González Guillén, María Diamanti, Beatriz Casado Ramón.

Hospital Comarcal El Escorial, Madrid: Sara Gayoso Martín.

Hospital Do Salnes, Villagarcia de Arosa, Pontevedra: María Goretti Sánchez Sindín.

Hospital de Barbanza, Ribeira, A Coruña: Azucena Prieto Zapico, Jésica Pazos González.

Hospital del Mar, Barcelona: M. Carmen Petrus Rivas, Bárbara Gómez y Gómez, Isabel Cirera Lorenzo, Patricia Gallardo Vizcaíno.

Hospital Santa Creu y Sant Pau, Barcelona: Aitor Alquezar Arbé, Paola Ponte Márquez, Carlos Romero Carrete, Sergio Pérez Baena, Laura Lozano Polo, Roser Arenós Sambro, José María Guardiola Tey.

Hospital de Vic, Barcelona: Lluís Llauger.

Hospital Valle del Nalón, Langreo, Asturias: Cesar Roza Alonso, Ana Murcia Olagüenaga.

Hospital Altagracia, Manzanares, Cuidad Real: Francisco Javier Díaz Miguez.

Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado, Talavera de la Reina, Toledo: Ricardo Juárez González, Mar Sousa, Laura Molina.

Hospital Universitario Vinalopó, Elche, Alicante: Pedro Ruiz Asensio, Esther Ruescas, María Martínez Juan.

Hospital de Móstoles, Madrid: Fátima Fernández Salgado, Eva de las Nieves Rodríguez, Gema Gómez García.

Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville: Amparo Fernández-Simón Almela, Esther Pérez García, Pedro Rivas del Valle, María Sánchez Moreno, Rafaela Ríos Gallardo, Laura Redondo Lora, Teresa Pablos Pizarro, Mariano Herranz García.

Hospital General Universitario Dr. Peset, Valencia: María Amparo Berenguer Diez, María Ángeles de Juan Gómez, María Luisa López Grima, Rigoberto Jesús del Río Navarro.

Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca: Núria Perelló Viola, Bernardino Comas Diaz, Sandra Guiu Martí, Juan Domínguez Casasola.

Clínica Universitaria Navarra, Madrid: Lourdes Hernández-Castells.

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia: José J. Noceda Bermejo, María Teresa Sánchez Moreno, Raquel Benavent Campos, Jacinto García Acosta, Alejandro Cortés Soler.

Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo: María Teresa Maza Vera, Raquel Rodríguez Calveiro, Paz Balado Dacosta, Violeta Delgado Sardina, Emma González Nespereira, Carmen Fernández Domato, Elena Sánchez Fernández-Linares.

Hospital Universitario de Salamanca: Ángel García García, Francisco Javier Diego Robledo, Manuel Ángel Palomero Martín, Jesús Ángel Sánchez Serrano.

Hospital de Zumárraga, Gipuzkoa: Patxi Ezponda.

Hospital Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor, San Javier, Murcia: Juan Vicente Ortega Liarte.

Hospital Virxe da Xunqueira, A Coruña: Andrea Martínez Lorenzo.

Hospital Universitario Río Ortega, Valladolid: Virginia Carbajosa Rodríguez, Susana Sánchez Ramón, Inmaculada García Rupérez, Pablo González Garcinuño, Raquel Hernando Fernández.

Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva: José María Santos Martín, Setefilla Borne Jerez, Asumpta Ruiz Aranda, María José Marchena.

Hospital Central Asturias: Claudia Corugedo Ovies, Claudia Marinero Noval, Eugenia Prieto Piquero, Hugo Mendes Moreira, Isabel Lobo Cortizo, Jennifer Turcios Torres, Lucia Hinojosa Diaz, Jesús Santianes Patiño.