To assess the pneumonia incidence in Navarre, Spain, in the 2023–2024 season.

MethodsUsing electronic medical records, we evaluated the incidence of clinical pneumonia, positive pneumococcal antigen cases and Mycoplasma pneumoniae positive PCR cases by age groups from 2017–2018 to 2023–2024 season.

ResultsCompared to the average of the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 seasons, in the 2023–2024 season, pneumonia incidence rate increased by 73% overall and multiplied by 4.43 in the age group of 5–14 years. The rate of confirmed pneumococcal pneumonia increased by 63%, and that of M. pneumoniae multiplied by 19.

ConclusionPneumonia incidence was unusually high in all ages in the 2023–2024 season and was related to upsurges in pneumococcal and Mycoplasma diseases.

Evaluar la incidencia de neumonía en Navarra, España, en la temporada 2023-2024.

MétodosUtilizando registros médicos electrónicos, se evaluó la incidencia de neumonía clínica, de casos con antígeno de neumococo positivo y los casos de Mycoplasma pneumoniae confirmados por PCR, por grupos de edad, desde la temporada 2017-2018 hasta la 2023-2024.

ResultadosEn comparación con la media de las temporadas 2017-2018 y 2018-2019, en la temporada 2023-2024 la tasa de incidencia de neumonía total aumentó un 73% en todas las edades y se multiplicó por 4,43 en el grupo de edad de 5-14años. La tasa de neumonía neumocócica confirmada aumentó un 63% y la de Mycoplasma pneumoniae se multiplicó por 19.

ConclusiónLa incidencia de la neumonía fue inusualmente alta en todas las edades en la temporada 2023-2024, y este incremento estuvo asociado con los repuntes de las enfermedades neumocócicas y por Mycoplasma.

Community-acquired pneumonia is a frequent cause of medical consultation and hospital admission.1 Different microorganisms can cause pneumonia.2,3 The incidence of non-COVID-19 pneumonia declined during the COVID-19 pandemic and returned to previous levels in the 2022–2023 season.4 In the 2023–2024 season, several surveillance indicators suggested an increased incidence of pneumonia in Europe.4,5 In Navarre (∼670,000 inhabitants), Spain, clinically diagnosed pneumonia and microbiologically confirmed cases are electronically reported. This study analyzed these data to compare the incidence of pneumonia in the 2023–2024 season with previous seasons.

MethodsThe syndromic surveillance system is based on daily reporting of specific diagnosis codes from the electronic clinical records of the Navarre Health Service. We analyzed all cases with pneumonia diagnoses (code R81 of the International Classification of Primary Care version 2) from October 2017 to March 2024. This system included clinical diagnoses performed in primary health care and the emergency room, including those admitted to hospitals. Viral pneumonia (code R8102) and COVID-19 cases (code A7701) were excluded.

From the microbiological surveillance system, we obtained all positive results for pneumococcal antigen test in urine and Mycoplasma pneumoniae polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test in a respiratory specimen from patients with pneumonia. Repeated results for the same clinical event were excluded.

For the present study, pneumonia season was defined as the period from October 1 of one year to March 31 of the following year. Seasonal incidence rates were calculated using the covered population of each age group and year as the denominator and compared using rate ratios (RR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) obtained by the Byar's method.

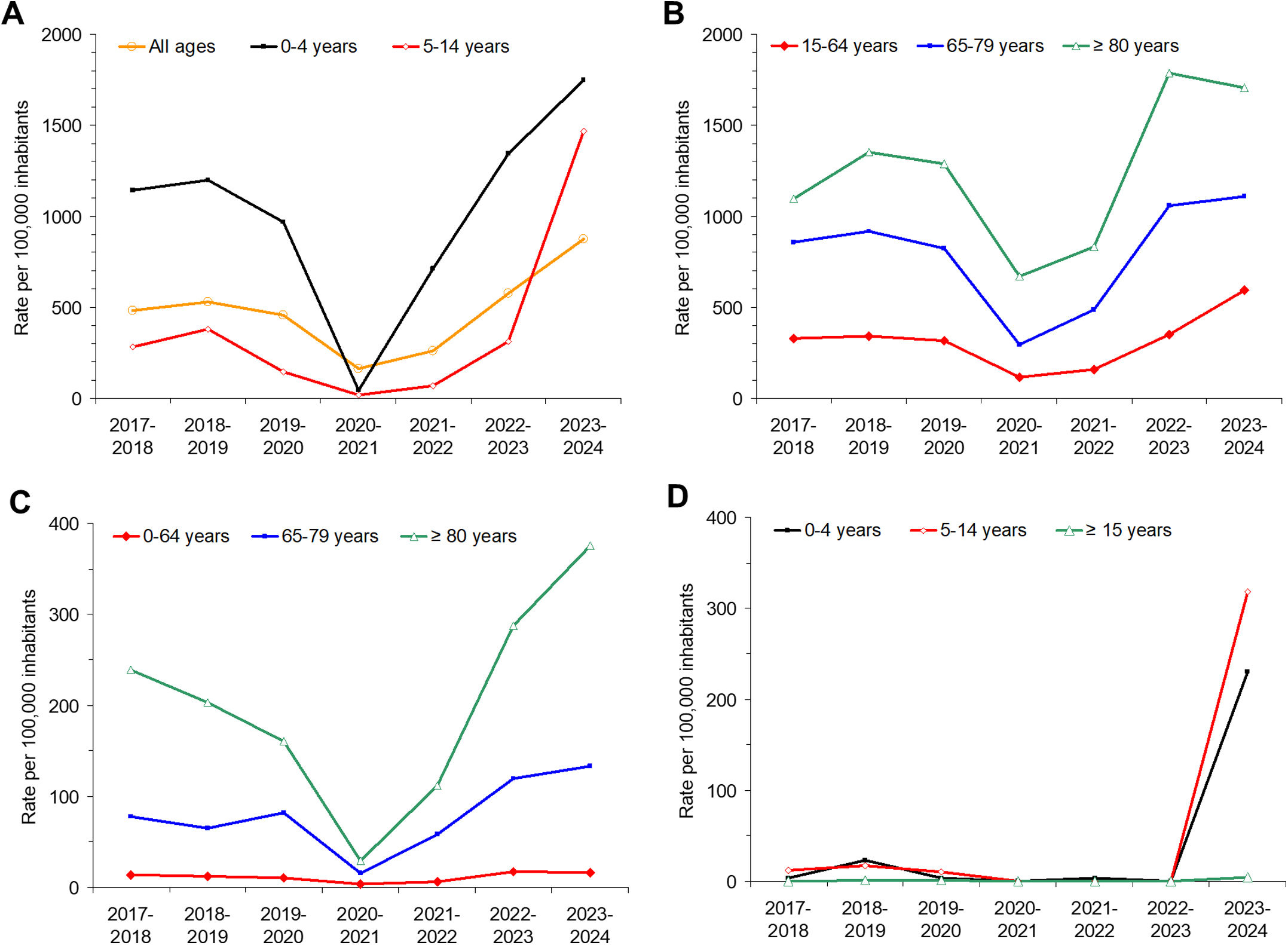

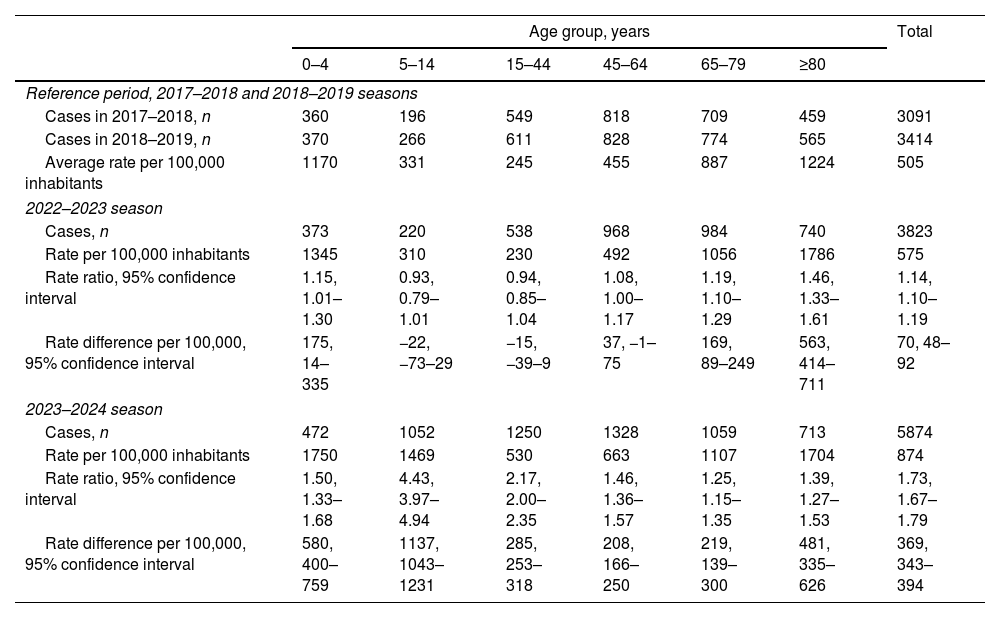

ResultsThe reference period included the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 seasons, with 3091 and 3414 cases of clinical pneumonia, and incidence rates of 481 and 528 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively. The incidence rate of pneumonia fell to 161 and 258 cases per 100,000 in the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 seasons, respectively, recovered the previous incidence level in the 2022–2023 season (575 cases per 100,000) and increased noticeably again in the 2023–2024 season (874 per 100,000) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Comparison of the pneumonia incidence in the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 seasons with the average of the seasons 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 by age groups, Navarre, Spain.

| Age group, years | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 5–14 | 15–44 | 45–64 | 65–79 | ≥80 | ||

| Reference period, 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 seasons | |||||||

| Cases in 2017–2018, n | 360 | 196 | 549 | 818 | 709 | 459 | 3091 |

| Cases in 2018–2019, n | 370 | 266 | 611 | 828 | 774 | 565 | 3414 |

| Average rate per 100,000 inhabitants | 1170 | 331 | 245 | 455 | 887 | 1224 | 505 |

| 2022–2023 season | |||||||

| Cases, n | 373 | 220 | 538 | 968 | 984 | 740 | 3823 |

| Rate per 100,000 inhabitants | 1345 | 310 | 230 | 492 | 1056 | 1786 | 575 |

| Rate ratio, 95% confidence interval | 1.15, 1.01–1.30 | 0.93, 0.79–1.01 | 0.94, 0.85–1.04 | 1.08, 1.00–1.17 | 1.19, 1.10–1.29 | 1.46, 1.33–1.61 | 1.14, 1.10–1.19 |

| Rate difference per 100,000, 95% confidence interval | 175, 14–335 | −22, −73–29 | −15, −39–9 | 37, −1–75 | 169, 89–249 | 563, 414–711 | 70, 48–92 |

| 2023–2024 season | |||||||

| Cases, n | 472 | 1052 | 1250 | 1328 | 1059 | 713 | 5874 |

| Rate per 100,000 inhabitants | 1750 | 1469 | 530 | 663 | 1107 | 1704 | 874 |

| Rate ratio, 95% confidence interval | 1.50, 1.33–1.68 | 4.43, 3.97–4.94 | 2.17, 2.00–2.35 | 1.46, 1.36–1.57 | 1.25, 1.15–1.35 | 1.39, 1.27–1.53 | 1.73, 1.67–1.79 |

| Rate difference per 100,000, 95% confidence interval | 580, 400–759 | 1137, 1043–1231 | 285, 253–318 | 208, 166–250 | 219, 139–300 | 481, 335–626 | 369, 343–394 |

In the 2023–2024 season, all age groups presented the highest incidence rates of pneumonia observed since 2017, except people aged 80 years and older, who reached the highest incidence in the 2022–2023 season (Fig. 1).

Compared with the average rate of the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 seasons (reference period for comparisons), in the 2023–2024 season, the rate increased 73% in all ages (RR=1.73; 95% CI 1.67–1.79), multiplied by 4.43 (95% CI 3.97–4.94) in the age group of 5–14 years, and by 2.17 (95% CI 2.00–2.35) in the age group of 15–44 years. The highest difference in pneumonia incidence rates was observed in people younger than 15 years, followed by those aged 80 years and older. Unlike other age groups, the incidence rate of people aged 80 years and older showed the main increase in the 2022–2023 season and remained in the 2023–2024 season (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

In the 2023–2024 season, 371 patients with pneumonia presented a positive pneumococcal urine antigen test (55 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, 24% of patients tested), reaching the highest incidence rate since 2017. This rate was 63% higher (RR=1.63; 95% CI 1.42–1.88) compared to that in the reference period for all ages, and the higher increases were observed in the age groups of 65–79 years (RR=1.86; 95% CI 1.45–2.39), and 80 years and older (RR=1.70; 95% CI 1.37–2.10) (Fig. 1). Among pneumococcal positive cases, 76.5% were 65 years old and older, 62% have received any pneumococcal vaccine and 13% have received a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Most pneumococcal confirmed cases were hospitalized (90%), ranging from 85% of those younger than 65 years to 92% of those aged 80 years and older.

In the 2023–2024 season, 314 cases were confirmed by PCR for M. pneumoniae, reaching an exceptionally high incidence rate (46.7 per 100,000 inhabitants; 22% of patients tested). This rate multiplied by 19.4 (95% CI 13.4–28.1; from 2.4 to 46.7 per 100,000) the average of the reference period. The incidence rate was higher in children younger than 5 years (230 per 100,000) and in those aged 5–14 years (318 per 100,000) (Fig. 1). Of all cases, 12% were admitted to the hospital. Most confirmed cases (92%) and hospitalized cases (76%) were under 15 years old.

Each of the other bacteria causing community-acquired pneumonia was detected in less than 50 cases each during the 2023–2024 season.

DiscussionWe found an exceptionally high incidence of pneumonia in the 2023–2024 season in Navarre, Spain, overall and in each age group. Although the increased incidence of pneumonia affected all ages, it was proportionally more pronounced in people younger than 45 years and especially in those aged 5–14 years. Since pneumonia incidence is usually higher in older people, a moderate increase in percentage among them represented an important increase in the number of cases.

The increases observed in the incidence of confirmed pneumococcal and M. pneumoniae diseases largely explained the increased incidence of pneumonia. Surveillance of respiratory viruses in the 2023–2024 season showed moderate waves of respiratory syncytial virus and COVID-19 with peaks in December and early January, respectively, and a slightly high incidence of influenza hospitalizations that peaked in the first week of January.5

M. pneumoniae disease usually presents low incidence,6 but it became a frequent infection in the 2023–2024 season, mainly affecting children younger than 15 years. Similar increases were reported in China7 and other European countries in late 2023,8–11 but we found that the increased incidence continued during the first quarter of 2024.

Pneumococcal disease is a frequent cause of pneumonia that affects all ages and, especially, older people.12 The observed increase of more than 60% in the incidence of confirmed pneumococcal pneumonia represented an important number of additional cases. There have been no recent changes in pneumococcal vaccination coverage that could explain the changes in the incidence in Navarre, where the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine was offered to all children and adults with high-risk conditions, and the polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine to all adults aged 65 years and older, reaching a coverage of 67%.13 Among invasive pneumococcal disease cases diagnosed in Navarre in 2023, 70% were due to serotypes not covered by the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, suggesting some serotype replacement.14

Other bacteria and viruses could also contribute to the increased incidence of pneumonia in the 2023–2024 season.15 Since viral infections could lead to bacterial pneumonia,3 the peaks of the seasonal influenza and COVID-19 epidemics could have influenced the increase in pneumonia.4 Nevertheless, the unusual excess of pneumonia cases contrasts with the normal incidence of viral infections observed in the 2023–2024 season.5,8

The important excess in pneumonia cases affecting all age groups and involving at least two different bacteria suggests a multi-causal phenomenon. The low circulation of some microorganisms during the COVID-19 pandemic might explain their intense re-emergence in the 2023–2024 season.4 Timely monitoring of pneumonia cases and specific causal agents supported the management of the unexpected increase in patients demanding health care.

These results have analyzed few indicators from population-based surveillance and may be subject to some limitations. The number of reported clinical cases of pneumonia is a quite sensitive indicator; however, most cases do not have an etiological diagnosis. Although unlikely, we cannot rule out the inclusion of any nosocomial pneumonia case. Confirmed diagnoses underestimate the actual number of cases. Many patients with pneumonia were not tested for antigen test, and, on the other hand, false-positive results are possible. Additionally, an unknown proportion of patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia were not tested by PCR.

The syndromic surveillance of pneumonia includes all cases diagnosed in the Navarre Health Service and has not experienced relevant changes during the study period, except those due to the introduction of the specific COVID-19 code. Although changes in clinical, diagnostic or codification practices could affect comparability over time, the consistent trends observed in different pneumonia-related indicators obtained from independent data sources (clinical diagnoses and microbiological confirmation) strongly suggest an unusual excess in pneumonia incidence.

ConclusionsAn unusually high incidence of community-acquired pneumonia has been detected in Northern Spain in the 2023–2024 season, affecting all ages and involving at least pneumococcal and M. pneumoniae. A simultaneous upsurge in the circulation of some microorganisms after the very low activity during the COVID-19 pandemic could explain this finding. Timely monitoring of pneumonia cases and specific causal agents helped to understand and address the situation.

Ethical approvalNo ethical approval was required for this study based on routine epidemiological and microbiological surveillance data.

FundingThis study was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III with the European Fund for Regional Development (CP22/00016 and PI23/01519).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.