The VINCat Program: a 19-year model of success in infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, Spain

Más datosThe VINCat programme focuses on monitoring surgical site infections (SSI) in caesarean sections (CS) performed across affiliated hospitals.

MethodsThe study included CS performed from 2008 to 2022, with a follow-up of 30 days after the intervention. The analysis of cumulative incidence rate of SSI was stratified into three 5-year periods (Periods 1–3). SSI was defined according to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) classification. SSI surveillance was carried out in accordance with the methodology established by the VINCat programme.

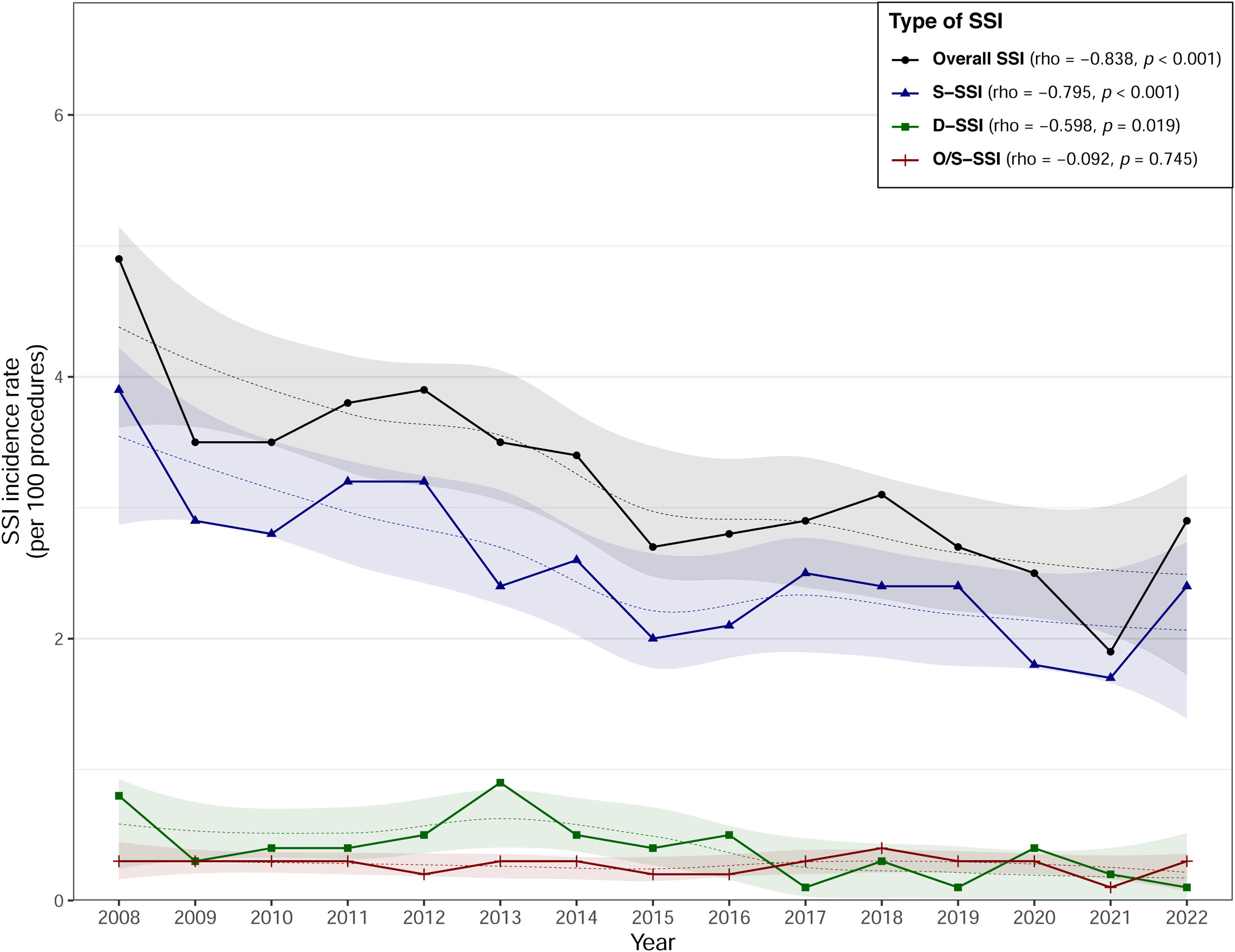

ResultsFrom 2008 to 2022, 36,387 CS were surveyed at 34 hospitals: 13,502 in Period 1, 12,985 in Period 2 and 9900 in Period 3. The mean age was 33 years. Overall, SSI incidence fell from 3.81% in Period 1 to 2.66% in Period 3 (rho=−0.838; p<0.001). Superficial SSI decreased from 3.1% in Period 1 to 2.15% in Period 3 (rho=−0.795; p<0.001). The rate of organ-space SSI remained consistent across all three periods, maintaining a rate of 0.27 (rho=−0.092; p=0.745). Culture was performed in 58.9% of infections. The microorganisms most frequently identified were Staphylococcus aureus (20.64%), Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) (13.52%), and Escherichia coli (11.27%). Antibiotic prophylaxis was appropriate in 73.76% of the procedures.

ConclusionsAppropriate monitoring of post-CS SSI rates allows the implementation of preventive measures to reduce their incidence.

El programa VINCat se centra en el seguimiento de las Infecciones de Localización Quirúrgica (ILQ) en las cesáreas realizadas en los hospitales afiliados.

MétodosEl estudio incluyó las cesáreas realizadas entre 2008 y 2022, con un seguimiento de 30 días tras la intervención. El análisis se estratificó en tres periodos de 5 años (periodos 1, 2 y 3). Las ILQ se definieron según los criterios de los Centers for Disease Control (CDC), y el riesgo quirúrgico según la clasificación de la National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). La vigilancia de las ILQ se llevó a cabo de acuerdo con la metodología establecida por el programa VINCat.

ResultadosDe 2008 a 2022, se realizaron 36.387 CS en 34 hospitales: 13.502 en el periodo 1, 12.985 en el periodo 2 y 9.900 en el periodo 3. La edad media de las pacientes fue de 33 años. La incidencia global de ILQ disminuyó del 3,81% en el periodo 1 al 2,66% en el periodo 3 (rho= -0,838; p<0,001). Las ILQ superficiales disminuyeron del 3,1% en el periodo 1 al 2,15% en el periodo 3 (rho= -0,795; p<0,001). La tasa de incidencia de ILQ órgano-espacio permaneció constante en los tres periodos, manteniendo una tasa de 0,27 (rho= -0,092; p = 0,745). Se realizaron cultivos en el 55,3% de las infecciones. Los microorganismos más frecuentemente identificados fueron S. aureus (20,64%), estafilococos coagulasa-negativa (13,52%) y E. coli (11,27%). La profilaxis antibiótica fue adecuada en el 73,76% de los procedimientos.

ConclusionesUna adecuada monitorización de las infecciones poscesárea y el análisis de las tasas de infección permiten implementar mecanismos para reducir su incidencia.

Caesarean section (CS) is one of the most common major surgical procedures. Data provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) show that the percentage of CS worldwide almost doubled between 2000 and 2015, rising from 12% to 21%.1

In Spain, the percentage of CS between 2010 and 2018 was 26.9%. The intervention is more frequent in women over 40 years of age, and the rate varies considerably between different autonomous communities.2 In Catalonia, CS deliveries account for 28.1% of the total, a rate that has remained stable over the last 15 years.3 It is more frequent in women over 35 years of age. One of the most common complications of CS is surgical site infection (SSI), which can increase morbidity and mortality rates and costs, and can also prolong hospital stay.4

A recent meta-analysis of 180 studies from 58 countries published between the years 2000–2023, including a population of 2,188,242 women, estimates the global incidence of post-CS SSI at 5.63% (95% CI 5.18–6.11%). In Africa the incidence is higher, at 11.91% (95% CI 9.67–14.34%). In the US the overall incidence is 3.72% (95% CI 2.91–4.64%). In Europe the global incidence is 4.45% (95% CI 3.66–5.31) with large differences between countries.5

Risk factors for post-CS SSI include chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes, duration of surgery>1h, blood loss>1000ml, emergency surgery, labour>24h, diabetes mellitus, obesity, high blood pressure, multiparity, gestational age and lack of prenatal medical care.6

This article describes the epidemiology of SSI in patients undergoing CS at Catalan hospitals affiliated to the VINCat Programme from 2008 to 2022.

MethodsPatient population and surveillance of SSIThe 34 hospitals (public and private) included in this analysis participated in the CS surveillance of SSI plan between 2008 and 2022. The number of hospitals varied between periods and decreased from 27 in Period 1 to 20 in Period 3 (Table 1). The hospitals are classified into three groups according to the number of beds: 3 large hospitals, with more than 500 beds; 9 medium-sized hospitals, ranging between 200 and 500 beds; and 22 small hospitals, with fewer than 200 beds.

Demographic data of patients and surgical characteristics of the procedures included in the caesarean section surgery programme.

| Characteristics | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=36,387 | N=13,502 | N=12,985 | N=9900 | ||

| Participating hospitals, n | |||||

| Number of hospitals | 34 | 27 | 25 | 20 | |

| Large | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Medium | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| Small | 22 | 18 | 15 | 12 | |

| Patient details | |||||

| Age, median (Q1–Q3) | 33.5 (29.77–36.99) | 32.75 (29.18–36.1) | 33.74 (29.98–37.11) | 34.33 (30.35–38.05) | <0.001 |

| ASA≥II, n (%) | 19,311 (53.07) | 6100 (45.18) | 6906 (53.18) | 6305 (63.69) | <0.001 |

| NISS≥1, n (%) | 8620 (23.69) | 2995 (22.18) | 3052 (23.5) | 2573 (25.99) | <0.001 |

| Surgery details | |||||

| Urgent | 18,844 (51.79) | 6765 (50.1) | 6990 (53.83) | 5089 (51.4) | <0.001 |

| Adequate prophylaxis, n (%) | 26,807 (73.67) | 10,960 (81.17) | 9601 (73.94) | 6246 (63.09) | <0.001 |

| Duration of intervention (minutes), median (Q1–Q3) | 42 (31–54) | 40 (29–54) | 40 (31–54) | 45 (35–54) | <0.001 |

Large: hospitals with >500 beds; Medium: hospitals with 200–500 beds; Small: hospitals with ≤200 beds; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; NNISS: National nosocomial infections surveillance system index. Adequate prophylaxis: type of antibiotic according to local guidelines, in addition to correct timing, dosage and duration.

The surveillance methodology is defined in the VINCat Programme Manual.7 Surveillance is active and continuous and must be carried out in all the procedures performed in a 1-year period. Infection Control Teams (ICT) at participating hospitals identify patients who have had a CS and have been followed up 30 days after surgery to screen for surgical infection.

Demographic data and other information relating to the intervention and surveillance are recorded on a data collection sheet at all hospitals and are then transferred to a VINCat programme database. Table S5 shows the surveillance methodology applied during hospital admission and after discharge for CS, and Table S6 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria. CS is a procedure with a very short hospital stay, and telephone monitoring after discharge is an option if adequate supervision by other means is not possible. SSI was defined according to National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) surveillance definition.8

Study designMulticenter, prospective cohort study of surveillance for CS-related infections in Catalonia (8million population), Spain. The study compares three 5-year periods: January 2008 to December 2012 (Period 1); from January 2013 to December 2017 (Period 2); and from January 2018 to December 2022 (Period 3).

Interventions implemented during the surveillance periodThe PREVINQ-CAT programme was created by a multidisciplinary group in 2017, and it began operations in 2018. The programme introduces a bundle of six general evidence-based measures to prevent surgical infection, which are presented in Table S7. Since 2017, surgical antibiotic prophylaxis has only been assessed in elective CS. Prophylaxis is considered correct if the antibiotic was administered in the 60min prior to the surgical incision.

Study outcomes, variables, definitions and data sourceThe primary outcome was the occurrence of SSI within 30 days after CS, as specified by the CDC's National Healthcare Safety Network definitions.8 Type of SSIs was classified as superficial incisional (S-SSI), deep incisional (D-SSI) and organ space (O/S-SSI). The term “overall SSI” refers to the sum of the SSI at all three anatomical levels. The cumulative incidence of SSIs was measured in events per 100 procedures included.

Secondary variables included LOS (length of stay), readmission rates, and the microbiological aetiology of infections. Basic demographic data such as age, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score were recorded. Additionally, information on surgical details, including surgical approach, adequate prophylaxis, and duration of surgery, was collected. The National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) score was also calculated for each patient. Participating hospitals with fewer than 10 cases per year were excluded from the analysis. Process and outcome data were collected locally and submitted via a web form.

Statistical analysisThe data were summarized using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. For continuous variables, we presented medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviations, depending on the distribution. Infection rates were expressed as cumulative incidence, i.e. the crude percentage of operations resulting in SSIs/number of surgical procedures. Analyses were stratified by 5-year periods, risk index category, hospital group and type of SSI. To assess differences in percentages, we conducted Chi-square tests or Fisher's tests, as deemed suitable. For continuous variables, comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test, as appropriate. Odds ratios (OR) were computed to compare the likelihood of SSI between two time periods. When comparing periods by OR, we assessed the two most recent periods, considering the earlier of those two as the reference.

To evaluate the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between infection rates, length of stay (LOS) and post-discharge SSI over the years, we performed a Spearman correlation (rho). A significance level of 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests. Additionally, LOESS smoothing was applied to the graphs to enhance the clarity in depicting data trends. Furthermore, we constructed boxplots representing annual surgical site infection rates for each hospital and we computed the mean and percentiles (25th, 50th, and 75th) for infection rates within each of the three hospital size categories. The results were analyzed using the R statistical software version 4.2.2, developed by The R Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

ResultsBetween 2008 and 2022, 36,387 CS carried out at 34 centres were included in the CS surveillance programme. Of these, 13,502 corresponded to Period 1; 12,985 to Period 2; and 9900 to Period 3. Further characteristics of the population are displayed in Table 1. Significant differences were observed in all the population characteristics among the three periods.

Trends over time in SSI incidence ratesFig. 1 and Fig. S2 show the trends of SSI incidence over the course of the study period. There were 1179 SSIs, representing a cumulative incidence of 3.24%. The annual evolution shows a significant and strongly negative correlation between the infection rate and the year of study (rho=−0.838, p<0.001). This indicates a clear downward trend in the infection rate as the years passed, suggesting that over time there was a steady fall in the overall SSI, with both S-SSI and D-SSI also showing a statistically significant decrease, while the O/S-SSI remained unchanged. Additionally, when comparing Period 2 and Period 3, as shown in Table 2, the overall SSI rate was 3.1 in Period 2 and decreased to 2.66 in Period 3 (OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.73–1.00). Furthermore, this reduction was more pronounced in D-SSI, with a rate of 0.52 in Period 2 and 0.23 in Period 3 (OR=0.45, 95% CI 0.28–0.72).

Trends in caesarean section related surgical site infections rates during the VINCat Programme surveillance period (2008–2022).

| Primary outcomes | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=36,387 | N=13,502 | N=12,985 | N=9900 | ||

| Overall SSI | 1179 (3.24) | 514 (3.81) | 402 (3.10) | 263 (2.66) | 0.86 (0.73–1.00) |

| S-SSI | 933 (2.56) | 419 (3.10) | 301 (2.32) | 213 (2.15) | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) |

| D-SSI | 149 (0.41) | 59 (0.44) | 67 (0.52) | 23 (0.23) | 0.45 (0.28–0.72)* |

| O/S-SSI | 97 (0.27) | 36 (0.27) | 34 (0.26) | 27 (0.27) | 1.04 (0.62–1.73) |

SSI: surgical site infection; S-SSI: superficial incisional site infection; D-SSI: deep incisional site infection; O/S-SSI: organ/space surgical site infection; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

The distribution of SSI rates according to hospital size, spread over the three-time groups studied is shown in Table 3. A homogeneous decrease in overall SSI was observed in medium and small-sized institutions, while an increase in SSI rates was observed in large hospitals. Notably, the cumulative incidence rate of O/S-SSI increased between periods for large hospitals, with only one large hospital participating in Period 3. This trend necessitates careful interpretation, as it may reflect hospital-specific factors rather than a generalizable trend.

Distribution of surgical site infections rates according to hospital size.

| Overall SSI | S-SSI | D-SSI | O/S-SSI | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital size | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a |

| Large | 3.6 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 1.44 (0.85–2.40) | 3.11 | 3.54 | 3.59 | 1.02 (0.56–1.81) | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.93 (0.19–17.94) | 0.14 | 0.11 | 1.6 | 7.43 (1.85–60.05)* |

| Medium | 4.1 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 0.81 (0.62–1.04) | 3.25 | 2.48 | 2.15 | 0.87 (0.65–1.15) | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.51 (0.22–1.07) | 0.35 | 0.2 | 0.16 | 0.78 (0.26–2.13) |

| Small | 3.6 | 3 | 2.5 | 0.84 (0.67–1.04) | 2.98 | 2.05 | 2.02 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.39 (0.20–0.71)* | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.73 (0.36–1.42) |

P1: Period 1 (2008–2012); P2: Period 2 (2013–2017); P3: Period 3 (2018–2022); SSI: surgical site infection; S-SSI: superficial incisional site infection; D-SSI: deep incisional site infection; O/S-SSI: organ/space surgical site infection; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence Interval.

Other patient outcomes are shown in Supplementary Table S8. Surgical site infections were diagnosed during post-discharge surveillance in 1039 (88.96%) patients. The rates of post-discharge SSI and readmissions increased progressively in all three periods (rho=0.471, p=0.076).

The median postoperative LOS for the overall study period was 4 days (IQR 3–4). Between Period 1 and Period 3, a consistent stability was observed, with no substantial change in LOS, ranging from 4 days in Period 1 to 3 days in Period 3 (rho=−0.164, p=0.560).

Microbiology of SSITable 4 details the aetiology of post-caesarean surgical site infections (SSI). Cultures were obtained from 695 (58.9%) of 1179 patients with SSI. Of these, 473 (68%) were monomicrobial infections, 166 (23.8%) were polymicrobial, and 56 (8%) had negative culture results. A total of 843 microorganisms were isolated, with 45.57% being Gram-positive cocci (GPC) and 35.23% being Gram-negative bacilli (GNB). The most frequently identified microorganisms included Staphylococcus aureus (20.64%), Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) (13.52%), and Escherichia coli (11.27%), while yeast and anaerobes were infrequently detected. Significant differences in the prevalence of GPC and GNB were observed across Periods 1–3, with a marked reduction in GPC (51.96–36.31%) and an increasing trend in GNB (34.56–42.26%) respectively.

Aetiology of caesarean section related surgical site infections.

| Family/microorganism | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Number of isolates,N | 843 | 408 | 267 | 168 | |

| Gram-positive cocci | 401 (47.57) | 212 (51.96) | 128 (47.94) | 61 (36.31) | 0.003 |

| S. aureus | 174 (20.64) | 101 (24.75) | 43 (16.1) | 30 (17.86) | 0.015 |

| CoNS | 114 (13.52) | 63 (15.44) | 39 (14.61) | 12 (7.14) | 0.025 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 61 (7.24) | 25 (6.13) | 22 (8.24) | 14 (8.33) | 0.485 |

| Other | 52 (6.17) | 23 (5.64) | 24 (8.99) | 5 (2.98) | 0.033 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 297 (35.23) | 141 (34.56) | 85 (31.84) | 71 (42.26) | 0.079 |

| Other GNB | 126 (14.95) | 57 (13.97) | 41 (15.36) | 28 (16.67) | 0.694 |

| Escherichia coli | 95 (11.27) | 45 (11.03) | 24 (8.99) | 26 (15.48) | 0.112 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 42 (4.98) | 23 (5.64) | 10 (3.75) | 9 (5.36) | 0.527 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 34 (4.03) | 16 (3.92) | 10 (3.75) | 8 (4.76) | 0.860 |

| Yeasts | 5 (0.59) | 3 (0.74) | 1 (0.37) | 1 (0.6) | 1.000 |

| Other yeasts | 4 (0.47) | 2 (0.49) | 1 (0.37) | 1 (0.6) | 1.000 |

| Candida spp. | 1 (0.12) | 1 (0.25) | – | – | – |

| Anaerobes | 16 (1.9) | 7 (1.72) | 4 (1.5) | 5 (2.98) | 0.508 |

| Other anaerobes | 9 (1.07) | 3 (0.74) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.19) | 0.611 |

| Bacteroides spp. | 6 (0.71) | 3 (0.74) | – | 3 (1.79) | 0.365 |

| Clostridium spp. | 1 (0.12) | 1 (0.25) | – | – | – |

| Other | 124 (14.71) | 45 (11.03) | 49 (18.35) | 30 (17.86) | 0.014 |

CoNS: coagulase-negative Staphylococci; GPB: Gram-positive bacteria; GNB: Gram-negative bacteria.

This study presents the results of the surveillance of infection in CS carried out in the hospitals in Catalonia affiliated to the VINCat Programme over the last 15 years. Most hospitals are small (with fewer than 200 beds) or medium-sized (with between 200 and 500 beds) and four are public and 30 private funded by Catalan Health Service.

To homogenize the surveillance results, the ICT received training regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the infection surveillance methodology, in accordance with the provisions of the VINCat Programme Manual.7 The managers of the programme also carried out a validation of the structure of the ICT, the surveillance process and the data sent by the hospitals to the Programme Coordinating Center to ensure its reliability.9

The cumulative incidence of post-CS infection was 3.24%, with a downward trend over the course of the period studied in small and medium-sized hospitals. A recent meta-analysis reported notable geographical differences in CS rates, from 3.87% in the US and 11.91% in Africa. The rate observed in our study is lower than the overall rate in Europe (4.42%), where significant variability is observed both in the number of studies and in the infection rates between countries, which range from 0.51 to 19.55%; the rate reported in one Spanish study was 3.41%.5 A 2018–2020 surveillance report carried out by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported an infection rate in CS of 1.3% (0.5–3.6) and, as in our study, a downward trend in infections over the 3-year period. Seven of the 13 EU countries included in the report stated that they performed post-discharge surveillance of SSIs based on the testimonies of either patients or surgeons and general practitioners.10

Most infections recorded in our study were superficial-incisional. The rate of organ-space infections was 0.27%, with no significant differences observed based on hospital size, except for one large university hospital in Period 3. Notably, the proportion of samples taken for culture increased from 30% in Period 1 to 60% in Period 3.

A retrospective study conducted in Ireland between 2005 and 2016 that included 219,859 CS reported a rate of detection of superficial infection during admission of 0.63%.11 This rate differs from those reported in other studies incorporating post-discharge surveillance, in which post-CS infection rates were between 3 and 15%.12 Without post-discharge surveillance, 88.89% of the infections in our study would not have been diagnosed; these events would probably have been relatively mild and would have been detected and treated in the community. The methods used to carry out post-discharge surveillance include telephone interviews 30 days after discharge13 and the use of mobile applications.14,15 Currently there is no gold standard for post-discharge surveillance. The ideal method should ensure a high follow-up rate, should not be excessively time-consuming, should be cost-effective and should offer high sensitivity and specificity.13,16

Comparison of the infection rates in the three periods analyzed indicates a fall over time. In the third period, the decrease in infection rates may be related to the implementation of the package of six general preventive measures. A meta-analysis published in 2017 demonstrated significantly lower infection rates in CS after the application of bundles, despite the heterogeneity of the studies analyzed and the differences in the components of the bundles.17 Other studies have shown that the application of bundles that include skin preparation, antibiotic prophylaxis administered before the incision, not removing skin hair if unnecessary, and maintaining normothermia reduces the infection rate in CS.18,19 Surprisingly, despite the implementation of the prevention bundle, the percentage of appropriate surgical antibiotic prophylaxis administered during Period 3 was lower than in previous periods. Differences in adherence to protocols, variations in staff training, and resource availability could have impacted the consistent application of adequate prophylaxis. Furthermore, with the implementation of PREVINQ-CAT, there may have been a heightened focus on monitoring and reporting practices. This increased scrutiny might have led to more rigorous reporting of instances where prophylaxis did not meet the established criteria, thereby reflecting a decrease in adequate prophylaxis rates.

In our study, the most frequently identified microorganisms responsible for post-CS infections were S. aureus, CoNS and E. coli. These findings align with the data reported by the ECDC for the period 2018–2020 regarding S. aureus and CoNS. However, our study observed a higher rate of E. coli infections. Other studies have also identified E. coli as the second most frequently involved microorganism in post-caesarean section SSIs.20,21

Limitations of the study: due to the length of time studied, the results may contain the effect of different changes in surgical practice and in the organization of the health care system. As in other surveillance databases, the number of variables collected was restricted, and some valuable factors such as body mass index, diabetes and smoking were not assessed. Adherence to the preventive bundle, intended for application across all participating hospitals, was challenging and not documented. The adherence to preventive bundle designed to be applied across all participating hospitals, was challenging and not recorded. Furthermore, we acknowledge the limitation posed by varying hospital participation across the study periods and the inherent difficulties in collecting superficial SSI, which are generally mild and managed by primary care physicians. Our primary analysis includes all hospitals to reflect real-world conditions. Future studies should aim for consistent participation to minimize potential biases. Finally, self-reported data can be a potential source of bias, although several validation actions were carried out to mitigate this issue.

This study also has several strengths. It is grounded on a large population and a high volume of cases followed up according to a consolidated, audited, and reviewed reporting method. Although the programme is based on voluntary hospital participation, almost all public hospitals in the area and several private-public funding institutions are included. We believe that the inclusion of different types and sizes of hospitals may make the results generalizable to other settings.

In conclusion, continuous surveillance and detailed knowledge of infection rates in caesarean section are essential for implementing preventive measures among VINCat hospitals.

Publishing ethicsThe study was conducted by the VINCat caesarean coordination team as a performance improvement project.

The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, with international human rights, and with the legislation regulating biomedicine and personal data protection. All data were treated as confidential, and records were accessed anonymously. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bellvitge Hospital (Ref. PR066/18). Patient data was anonymized, and so the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research.

The study is reported in accordance with the STROCSS 2021 criteria.

FundingThe VINCat Programme is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this article. All authors submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and the conflicts that the editors consider relevant to this work are disclosed here.

Data availability statementRestrictions apply to the availability of these data, which belong to a national database and are not publicly available. Data was obtained from VINCat and are only available with the permission of the VINCat Technical Committee.

This article is our original work, has not been previously published, and is not under consideration elsewhere. All named authors are appropriate co-authors, and have seen and agreed to the submitted version of the paper.

The authors wish to thank CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support, and all nurses and physicians in the participating hospitals involved in gathering and reporting their infection data.

Vicens Diaz-Brito Fernandez, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Deu. Hospital de Sant Boi; Mª Teresa Ros Prat, Fundació Sant Hospital. La Seu d’Urgell; María Ramirez Hidalgo and Elisa Montiu González, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida; Montserrat Olona Cabases and Antonia Garcia Pino, Hospital universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona; David Blancas Altabella and Esther Moreno Rubio, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedès i Garraf – Hospital Sant Camil; Roger Malo Barres and Marilo Marimon Moron, Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya; Francisco José Vargas-Machuca Fernández and Mª de Gracia García Ramírez, Centre MQ Reus; Ricardo Gabriel Zules Oña, Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta; Alba Guitard Quer, Hospital Universitari Santa Maria; Anna Besolí Codina, Consorci hospitalari de Vic; Simona Iftimie and M. Rosa Prieto Butille, Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus; Maria de la Roca Toda Savall, Mª Luisa Monje Beltran and Arantzazu Mera Fidalgo, Hospital de Palamós; Josep Cucurull Canosa and Carme Burgas Balibrea, Hospital de Figueres; Dolors Rodriguez-Pardo and Elisa Navarro Royo, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Pilar de la Cruz, Hospital Universitari Dexeus; Marta Milián Sanz and Alexandra Lucia Moise, Hospital Pius de Valls; Yolanda Meije Castillo, Hospital de Barcelona.SCIAS; José Carlos de la Fuente Redondo and Montserrat Nolla Ávila, Hospital Comarcal de Móra d’Ebre; Eva Palau Gil and Yurisel Ramos Fernandez, Clinica Girona; Elisabet Lerma Chippirraz and Demelza Maldonado López, Hospital General de Granollers; Josep Farguell Carreras and Mireia Saballs Nadal, Hospital QuironSalud Barcelona; Ludivina Ibáñez Soriano and Mª Angeles Ariño Ariño, Espitau Val d’Aran; Angels Garcia Flores and Roser Ferrer i Aguilera, Hospital Sant Jaume de Calella; Núria Bosch Ros, Hospital Sta. Caterina Girona; Sandra Insa Mone, Aroa Sancho Galan, Montserrat Carrascosa Carrascosa and Teresa Domenech Forcadell, Clinica Terres de l’Ebre; Laura Linares Gonzalez and María Cuscó Esteve, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedès i Garraf. Hospital Alt Penedés; Nerea Roch Villaverde and Joaquín López-Contreras Gonzalez, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Rafel Perez Vidal, Elena Gomez Valencia and Dolors Mas Rubio, Althaia, Xarxa Assistencial Universitària de Manresa. Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Manresa; Nieves Sopena Galindo, Montserrat Gimenez Perez and Elvira Carballas Valencia, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol; Elena Vidal Diez, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme. Hospital de Mataró.