The VINCat Program: a 19-year model of success in infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, Spain

Más datosColorectal surgery has the highest surgical site infection (SSI) rates of all abdominal surgeries. Epidemiological surveillance is an excellent instrument to reduce SSI rates, but its effects may be time-limited and need to be monitored periodically. This study analyses the effectiveness of an interventional surveillance programme with regard to reducing SSI rates after elective colorectal surgery.

MethodsCohort study analysing a SSI surveillance programme in elective colorectal surgery over a 15-year period. Prospectively collected data were stratified by 5-year periods (Periods 1, 2 and 3), and SSI rates, length of stay, readmission, mortality and microbiological aetiology were investigated.

ResultsA total of 64,074 operations were included (42,665 colon surgery and 21,409 rectal surgery). Overall SSI incidence in colon surgery fell from 19.6% in Period 1 to 7.6% in Period 3 (rho=−0.961). Organ-space SSI (O/S-SSI) was 8.3% in Period 1 and 4.7% in Period 3 (rho=−0.815). In rectal surgery, overall SSI fell from 20.6% to 12.8% (rho=−0.839), and O/S-SSI from 8.5% to 8.3%, the latter difference being non-significant. The intervention that achieved the greatest SSI reduction was a preventive bundle comprising six measures. Hospital stay and mortality rates decreased, while SSIs after discharge and readmissions increased. An increase in Gram-positive cocci and fungi, and reductions in Gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes were detected for both incisional and O/S-SSI.

ConclusionsDetailed analysis of SSI rates allows the design of strategies for reducing their incidence. An interventional surveillance programme was effective in decreasing SSI rates in colorectal surgery.

La cirugía colorrectal presenta las tasas de infección de localización quirúrgica (ILQ) más elevadas de la cirugía abdominal. La vigilancia epidemiológica las reduce, pero sus efectos pueden ser limitados y deben supervisarse periódicamente. Este estudio analiza la eficacia de un programa de vigilancia intervencionista en la reducción de las tasas de ILQ tras cirugía colorrectal.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes analizando un programa de vigilancia en cirugía colorrectal electiva durante 15 años. Los datos recogidos prospectivamente se estratificaron por periodos de 5 años (Periodos 1, 2 y 3). Se investigaron tasas de ILQ, duración de estancia, reingresos, mortalidad y microbiología.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 64.074 operaciones (42.665 cirugía de colon y 21.409 cirugía rectal). La ILQ en cirugía cólica descendió del 19,6% en el Periodo 1 al 7,6% en el Periodo 3 (rho=−0,961). La ILQ órgano-espacio (ILQ-O/E) fue del 8,3% en el Periodo 1 y del 4,7% en el Periodo 3 (rho=−0,815). En cirugía rectal, la ILQ descendió del 20,6 al 12,8% (rho=−0,839) y la ILQ-O/E del 8,5 al 8,3%, siendo esta última no significativa. La intervención con eficacia fue la implantación de seis medidas preventivas. La estancia hospitalaria y mortalidad disminuyeron, pero aumentaron ILQ postalta y reingresos. Hubo un aumento de cocos grampositivos y hongos, y reducción de bacterias gramnegativas y anaerobios, en ILQ incisionales e ILQ-O/E.

ConclusionesEl análisis detallado de las tasas de ILQ permite diseñar estrategias para reducir su incidencia. Este programa de vigilancia intervencionista resultó eficaz para disminuir las tasas de ILQ en cirugía colorrectal.

Among abdominal surgeries, colorectal surgery has the highest rate of surgical site infection (SSI), ranging from 15% to 30% in some studies.1 The most dreaded complication of this surgery is organ/space SSI (O/S-SSI) which triples hospital length of stay (LOS), lengthens intensive care unit stay, and raises readmission and re-intervention rates, thus incurring a substantial increase in costs.2

SSI surveillance is one of the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s core components for effective infection prevention and control programmes.3 Although epidemiological surveillance with feedback to providers has been shown to be an excellent means of reducing SSI rates,4,5 a “dilution” of the surveillance effect has been reported after five years of surveillance.5 Some authors suggest that surveillance programmes should include dynamic interventions so as to improve outcomes.6

This nationwide cohort study analyses the effectiveness of a national surveillance programme with regard to reducing the SSI rate after elective colorectal surgery over a 15-year timespan. Specifically, it investigates the impact of several improvements introduced over this period, above all the consecutive implementation of two specific care bundles.

Material and methodsVINCat Colorectal Surveillance ProgrammeSince 2008, the VINCat Programme has been conducting active surveillance of SSIs in elective colorectal surgery at public and private hospitals in Catalonia, Spain. The structure of the programme has been described in detail elsewhere.7 The results of this quality improvement project for the period from 2008 to 2022 are analysed here. Infection control teams (ICTs) at each hospital conducted prospective surveillance following the standardised programme methodology described in Table S1. A detailed computerised operational document was shared with all hospitals in the network and was modified every year, with the occasional inclusion of changes in methodology or definitions. The structure and surveillance process, as well as its results, were validated periodically by researchers with specific training and full knowledge of the methodology. ICT staff conducting surveillance had been trained in surveillance methodology to ensure homogeneous and accurate data collection. Several training meetings were held with the staff in order to standardise data collection.

Cases of elective wound class 2 (clean-contaminated) and 3 (contaminated) according to the National Healthcare Safety Network classification8 were followed. Patients with previous ostomies or active infection at the time of intervention (wound class 4) were excluded. Table S2 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria in detail. The hospitals were classified into three groups according to their complexity and number of hospital beds: >500 beds; 200–500 beds; ≤200 beds.

Mandatory active surveillance after discharge was conducted until postoperative day 30 using a multimodal approach, including electronic review of medical records (with access to out-of-hospital care notes), verification of readmissions, verification of emergency department visits, and review of microbiological and radiological data.

Study design, setting and patientsPragmatic, multicentre cohort study analysing a prospective SSI surveillance database run by the national network. The study compares three 5-year periods: from January 2008 to December 2012 (Period 1); from January 2013 to December 2017 (Period 2); and from January 2018 to December 2022 (Period 3). Sixty-one hospitals contributed cases in the analysis.

Interventions implemented during the surveillance periodIn 2010, the Colorectal Surgery Group, comprising infectious disease specialists and infection control staff, was expanded to include surgeons dedicated to surgical infections and colorectal surgeons. Data on colon and rectal surgery, which had been collected together for the first three years, were segregated from 2011 onwards. In 2015, a working group was formed in conjunction with the Societat Catalana de Cirurgia to develop a specific SSI prevention bundle. Starting in January 2016, this six-measure bundle was voluntarily implemented by the participating hospitals. The measures included are shown in Table 1. In 2017, a multidisciplinary group developed the PREVINQ-CAT prevention programme, which was implemented as of January 2018. This programme introduced a general bundle of six measures and an accessory bundle of six further measures, which were added to those in the specific bundle, constituting the final colorectal bundle (Table 1).

Measures included in the VINCat colorectal and PREVINQ-CAT bundles.

| Colorectal VINCat bundle – 2016 | PREVINQ-CAT bundle – 2018 |

|---|---|

| “Adequate” iv antibiotic prophylaxis | Preoperative shower |

| Mechanical bowel preparation | Adequate hair management |

| Oral antibiotic prophylaxis | Adequate surgical hand hygiene |

| Laparoscopic surgery | Skin antisepsis with CHG 2%-alcohol |

| Maintenance of normothermia | Control of perioperative glycaemia |

| Double-ring plastic wound edge retractor | Maintenance of normovolemia |

| Change of surgical instruments and gloves | |

| Wound irrigation with saline |

CHG 2%-alcohol: 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol.

The primary endpoint of the study was the occurrence of a SSI within 30 days of surgery, in accordance with CDC-NHSN (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention-National Healthcare Safety Network) definitions.9,10 SSIs were defined as superficial incisional (S-SSI), deep incisional (D-SSI) or O/S-SSI. SSIs were stratified into surgical procedure categories (−1 to 3) according to the risk of infection as defined by the NHSN. The incidence of SSIs was measured as events per 100 procedures included.

Secondary variables were length of hospital stay (LOS), readmission, 30-day postoperative mortality, and microbiological aetiology of infections. Basic demographic data were recorded, including age, gender, type of surgical procedures, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) operative risk score, wound contamination class, surgical approach, quality of antibiotic prophylaxis, and duration of surgery. The criteria used to consider antibiotic prophylaxis “adequate” took into account: the type of drug, the dose administered, the timing of infusion, its completion before the surgical incision, and the duration of therapy. A single deviation from the recommended guidelines was enough to consider the process inadequate. Participating hospitals with fewer than 10 cases per year were excluded from the analysis.

Ethical issues.Data extraction was approved by the Institutional Research Committee (code no. 20166009), and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital General de Granollers (code no. 2021006). The need for informed consent and for the provision of an information sheet was waived because the data were collected routinely as part of hospital surveillance and quality improvement practices. Anonymity and data confidentiality (access to records, data coding and archiving of information) were maintained throughout the research process. Confidential patient information was protected in accordance with European regulations. The study is reported in accordance with the STROCSS 2021 criteria.11 The project was registered with the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04496635 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04496635).

Statistical analysisData were summarised as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, and as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Infection rates were expressed as cumulative incidence, i.e., the crude percentage of operations resulting in SSIs/number of surgical procedures. Analyses were stratified by 5-year periods, risk index category, hospital group and type of SSI. To assess differences in percentages, we conducted chi-squared tests or Fisher's tests, as deemed suitable. For continuous variables, comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test, as appropriate. Crude odds ratios (OR) were computed from a table 2-by-2 to compare the likelihood of SSI between the two most recent periods, considering the earlier of those two as the reference. To evaluate the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between infection rates, 30-days mortality rates, length of stay (LOS) and post-discharge SSI over the years, a Spearman correlation (rho) was conducted. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all tests. In addition, LOESS smoothing was used in the graphics to better illustrate the trends in the data. Furthermore, we constructed boxplots representing annual surgical site infection rates for each hospital and we computed the mean and percentiles (25th, 50th, and 75th) for infection rates within each of the three hospital size categories. Results were analysed using the R statistical software version 4.2.2, developed by The R Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

ResultsThe study included 64,074 elective colorectal procedures, 42,665 of them colon surgery and 21,409 rectal surgery. The demographic characteristics and risk factors for SSI of the procedures included are displayed in Table 2. The use of the laparoscopic technique rose over the period under study in both colon and rectal surgery, while the duration of surgery and ASA score had statistical but clinically non-significant differences in all three periods.

Demographic data of patients and surgical characteristics of the procedures included in the colorectal surgery programme.

| Characteristics | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon surgery | N=42,666 | N=13,177 | N=14,866 | N=14,623 | |

| Participating hospitals, n | |||||

| Total | 59 | 51 | 56 | 57 | |

| Large | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Medium | 17 | 14 | 16 | 17 | |

| Small | 33 | 28 | 31 | 31 | |

| Age, median (Q1–Q3) | 70.45 (61.48–78.64) | 70.98 (61.36–78.52) | 69.78 (61.26–78.53) | 70.81 (61.82–78.88) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 17,845 (41.82) | 5,446 (41.33) | 6,212 (41.79) | 6,187 (42.31) | 0.253 |

| Clean-contaminated surgery, n (%) | 41,419 (97.08) | 12,357 (93.78) | 14,565 (97.98) | 14,497 (99.14) | <0.001 |

| Duration of intervention (min), median (Q1–Q3) | 157 (120–205) | 155 (120–200) | 151 (117–196) | 165 (127–214) | <0.001 |

| Adequate prophylaxis, n (%) | 36,424 (85.37) | 12,080 (91.67) | 12,192 (82.01) | 12,152 (83.1) | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopy, n (%) | 26,949 (63.16) | 5,823 (44.19) | 9,682 (65.13) | 11,444 (78.26) | <0.001 |

| ASA ≥II, n (%) | 39,911 (93.54) | 12,317 (93.47) | 13,971 (93.98) | 13,623 (93.16) | 0.016 |

| NISS ≥1, n (%) | 13,972 (32.75) | 5,389 (40.9) | 4,530 (30.47) | 4,053 (27.72) | <0.001 |

| Rectal surgery | N=21,410 | N=10,464 | N=5,860 | N=5,086 | |

| Participating hospitals, n | |||||

| Total | 57 | 50 | 43 | 42 | |

| Large | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Medium | 17 | 14 | 16 | 17 | |

| Small | 31 | 27 | 18 | 16 | |

| Age, median (Q1–Q3) | 69.42 (60.42–77.65) | 70.7 (61.19–78.2) | 68.37 (59.92–76.88) | 68.63 (59.68–77.3) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 8,109 (37.87) | 4,231 (40.43) | 2,027 (34.59) | 1,851 (36.39) | <0.001 |

| Clean-contaminated surgery, n (%) | 20,404 (95.3) | 9,693 (92.63) | 5,737 (97.9) | 4,974 (97.8) | <0.001 |

| Duration of intervention (min), median (Q1–Q3) | 185 (135–246) | 165 (120–215) | 205 (154–262) | 223 (170–280) | <0.001 |

| Adequate prophylaxis, n (%) | 18,598 (86.87) | 9,624 (91.97) | 4,736 (80.82) | 4,238 (83.33) | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopy, n (%) | 12,186 (56.92) | 4,362 (41.69) | 3,812 (65.05) | 4,012 (78.88) | <0.001 |

| ASA ≥II, n (%) | 20,046 (93.63) | 9,756 (93.23) | 5,513 (94.08) | 4,777 (93.92) | 0.065 |

| NISS ≥1, n (%) | 7,511 (35.08) | 4,384 (41.9) | 1,728 (29.49) | 1,399 (27.51) | <0.001 |

Large: hospitals with >500 beds; medium: hospitals with 200–500 beds; small: hospitals with ≤200 beds; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; NNISS: national nosocomial infections surveillance system index. Adequate prophylaxis: type of antibiotic according to local guidelines, in addition to correct timing, dosage and duration.

Fig. 1a shows the trends of SSI incidence. There were 5700 SSIs, representing a cumulative incidence of 13.4%. The overall SSI rate fell significantly over the years, dropping to 7.6% in Period 3. As regards the surgical site affected, 4.9% of infections were S-SSI, 1.9% D-SSI and 6.5% O/S-SSI (Table 3). There was a significant decrease in all three SSIs over the three study periods, falling to 2.2%, 0.7% and 4.7% respectively in Period 3.

Trends in colorectal SSI rates during the VINCat Programme surveillance period (2008–2022).

| Overall | Period 12008–2012 | Period 22013–2017 | Period 32018–2022 | OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon surgery | N=42,666 | N=13,177 | N=14,866 | N=14,623 | |

| Overall SSI | 5,700 (13.36%) | 2,588 (19.64%) | 2,004 (13.48%) | 1,108 (7.58%) | 0.56 (0.52–0.61) |

| S-SSI | 2,091 (4.9%) | 1,052 (7.98%) | 720 (4.84%) | 319 (2.18%) | 0.45 (0.39–0.51) |

| D-SSI | 825 (1.93%) | 448 (3.4%) | 270 (1.82%) | 107 (0.73%) | 0.40 (0.32–0.50) |

| O/S-SSI | 2,784 (6.53%) | 1,088 (8.26%) | 1,014 (6.82%) | 682 (4.66%) | 0.68 (0.62–0.76) |

| Rectal surgery | N=21,410 | N=10,464 | N=5,860 | N=5,086 | |

| Overall SSI | 3,855 (18.01%) | 2,154 (20.58%) | 1,051 (17.94%) | 650 (12.78%) | 0.71 (0.64–0.79) |

| S-SSI | 1,246 (5.82%) | 840 (8.03%) | 276 (4.71%) | 130 (2.56%) | 0.54 (0.44–0.67) |

| D-SSI | 722 (3.37%) | 427 (4.08%) | 199 (3.4%) | 96 (1.89%) | 0.56 (0.43–0.71) |

| O/S-SSI | 1,887 (8.81%) | 887 (8.48%) | 576 (9.83%) | 424 (8.34%) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) |

SSI: surgical site infection; S-SSI: superficial incisional site infection; D-SSI: deep incisional site infection; O/S-SSI: organ/space surgical site infection; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

The overall SSI rate was 18.0%, with a significant decrease from 20.6% in Period 1 to 12.8% in Period 3. While the S-SSI and D-SSI rates fell significantly over time, the overall O/S-SSI rate did not, remaining at 8.3% in Period 3 (Table 3 and Fig. 1b).

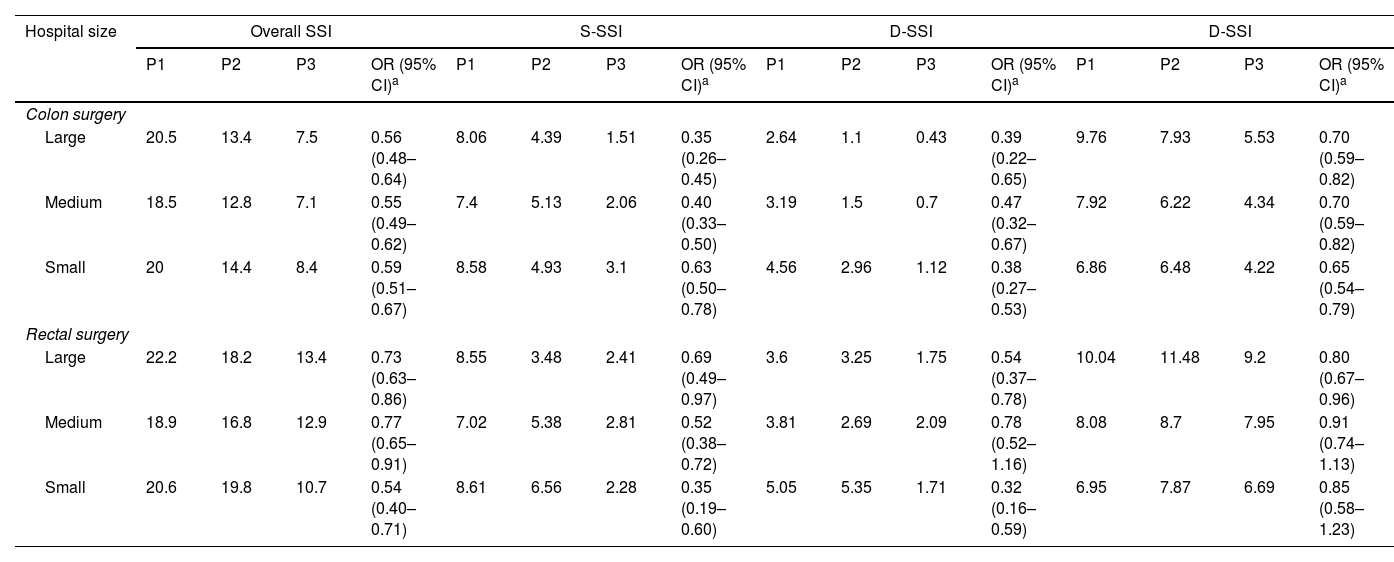

SSI according to size of hospital.Table 4 and Figs. S1 and S2 show the distribution of overall colon and rectal surgery SSI rates according to hospital size. A homogeneous decrease in overall SSIs was observed at all three types of institution, although significant differences were found in the crude rates by hospital volume. By surgical site levels, the decrease in incisional SSIs was significant and similar among the three hospital types. The rates of O/S-SSIs also decreased significantly, although they were higher for rectal surgery and at high complexity hospitals.

Distribution of SSI rates according to hospital size.

| Hospital size | Overall SSI | S-SSI | D-SSI | D-SSI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | P1 | P2 | P3 | OR (95% CI)a | |

| Colon surgery | ||||||||||||||||

| Large | 20.5 | 13.4 | 7.5 | 0.56 (0.48–0.64) | 8.06 | 4.39 | 1.51 | 0.35 (0.26–0.45) | 2.64 | 1.1 | 0.43 | 0.39 (0.22–0.65) | 9.76 | 7.93 | 5.53 | 0.70 (0.59–0.82) |

| Medium | 18.5 | 12.8 | 7.1 | 0.55 (0.49–0.62) | 7.4 | 5.13 | 2.06 | 0.40 (0.33–0.50) | 3.19 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.47 (0.32–0.67) | 7.92 | 6.22 | 4.34 | 0.70 (0.59–0.82) |

| Small | 20 | 14.4 | 8.4 | 0.59 (0.51–0.67) | 8.58 | 4.93 | 3.1 | 0.63 (0.50–0.78) | 4.56 | 2.96 | 1.12 | 0.38 (0.27–0.53) | 6.86 | 6.48 | 4.22 | 0.65 (0.54–0.79) |

| Rectal surgery | ||||||||||||||||

| Large | 22.2 | 18.2 | 13.4 | 0.73 (0.63–0.86) | 8.55 | 3.48 | 2.41 | 0.69 (0.49–0.97) | 3.6 | 3.25 | 1.75 | 0.54 (0.37–0.78) | 10.04 | 11.48 | 9.2 | 0.80 (0.67–0.96) |

| Medium | 18.9 | 16.8 | 12.9 | 0.77 (0.65–0.91) | 7.02 | 5.38 | 2.81 | 0.52 (0.38–0.72) | 3.81 | 2.69 | 2.09 | 0.78 (0.52–1.16) | 8.08 | 8.7 | 7.95 | 0.91 (0.74–1.13) |

| Small | 20.6 | 19.8 | 10.7 | 0.54 (0.40–0.71) | 8.61 | 6.56 | 2.28 | 0.35 (0.19–0.60) | 5.05 | 5.35 | 1.71 | 0.32 (0.16–0.59) | 6.95 | 7.87 | 6.69 | 0.85 (0.58–1.23) |

P1: Period 1 (2008–2012); P2: Period 2 (2013–2017); P3: Period 3 (2018–2022); SSI: surgical site infection; S-SSI: superficial incisional site infection; D-SSI: deep incisional site infection; O/S-SSI: organ/space surgical site infection; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Within each type of hospital there was a large variability in rates, with differences of up to 25 points between different centres. However, these intra-group differences were less pronounced in Period 3.

Other outcomesTable 5 shows the results of other patient outcomes. SSI was diagnosed during post-discharge surveillance in one third of patients, half of whom required readmission. The rates of post-discharge SSI and readmissions increased progressively in all three groups.

Secondary outcomes.

| Characteristics | Overall | Period 12008–2012 | Period 22013–2017 | Period 32018–2022 | Spearman correlation* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho | p | |||||

| Colon surgery | N=42,666 | N=13,177 | N=14,866 | N=14,623 | ||

| LOS, median (Q1–Q3) | 6 (5–10) | 8 (6–13) | 7 (5–10) | 5 (4–8) | −0.986 | <0.001 |

| 30-Days mortality | 461 (1.08) | 153 (1.16) | 201 (1.35) | 107 (0.73) | −0.455 | 0.102 |

| Post-discharge SSI | 1,531 (26.88) | 601 (23.24) | 566 (28.29) | 364 (32.85) | 0.882 | <0.001 |

| Rectal surgery | N=21,410 | N=10,464 | N=5,860 | N=5,086 | ||

| LOS, median (Q1–Q3) | 7 (5–13) | 9 (7–16) | 8 (6–13) | 6 (5–10) | −0.984 | <0.001 |

| 30-Days mortality | 168 (0.78) | 94 (0.9) | 48 (0.82) | 26 (0.51) | −0.536 | 0.048 |

| Post-discharge SSI | 1,061 (27.57) | 512 (23.78) | 326 (31.11) | 223 (34.41) | 0.718 | 0.003 |

Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile; Rho: Spearman's rank correlation coefficient; LOS: length of hospital stay; IQR: interquartile range; SSI: surgical site infection.

The median postoperative LOS for colon surgery was six days (IQR 5–10) and decreased significantly over time, falling to five days in Period 3. In rectal surgery, overall LOS was seven days; again, a significant decrease was observed, from nine days in Period 1 to six days in Period 3.

Mortality in the series decreased during the time frame of the study, being 0.7% for colon surgery and 0.5% for rectal surgery in Period 3. Only in rectal surgery was this decrease statistically significant.

Effect of interventionsThe main interventions implemented in the programme were spread over the three periods. In Period 1, the multidisciplinary colorectal group was expanded and data from colon and rectal surgery were separated. The intervention that achieved the highest reduction in SSI rate was the introduction of the VINCat preventive bundle, at the end of Period 2, which was associated with a 23% decrease in overall SSI during the first year of its implementation. Its effect was significant for both incisional and O/S-SSIs. With the application of the PREVINQ-CAT bundles at the beginning of Period 3, SSI rates continued to fall, albeit at a less pronounced rate.

Microbiology of SSITable 6 shows the results of microbiological isolates, grouped into S-SSI samples and deep samples (D-SSI plus O/S-SSI). A slight but non-significant increase in the isolation of Gram-positive cocci and fungi was detected in S-SSI in the last five-year period.

Aetiology of Incisional (I-SSI) and organ/space (O/S-SSI) surgical site infections of the colon and rectum.

| Period 12008–2012 | Period 22013–2017 | Period 32018–2022 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-SSI | ||||

| Gram-positive bacteria | 528 (24.14) | 278 (24.01) | 142 (28.98) | 948 (24.72) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 121 (5.53) | 41 (3.54) | 33 (6.73) | 195 (5.08) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 148 (6.77) | 82 (7.08) | 45 (9.18) | 275 (7.17) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 43 (1.97) | 33 (2.85) | 25 (5.1) | 101 (2.63) |

| CoNS | 87 (3.98) | 37 (3.2) | 21 (4.29) | 145 (3.78) |

| Other GPB | 129 (5.9) | 85 (7.34) | 18 (3.67) | 232 (6.05) |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 968 (44.26) | 588 (50.78) | 221 (45.1) | 1777 (46.34) |

| Escherichia coli | 591 (27.02) | 349 (30.14) | 104 (21.22) | 1044 (27.22) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 88 (4.02) | 72 (6.22) | 39 (7.96) | 199 (5.19) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 43 (1.97) | 32 (2.76) | 15 (3.06) | 90 (2.35) |

| Other GNB | 246 (11.25) | 135 (11.66) | 63 (12.86) | 444 (11.58) |

| Anaerobes | 96 (4.39) | 54 (4.66) | 14 (2.86) | 164 (4.28) |

| Clostridium spp. | 4 (0.35) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.13) | |

| Bacteroides spp. | 41 (1.87) | 29 (2.5) | 7 (1.43) | 77 (2.01) |

| Other anaerobes | 55 (2.51) | 21 (1.81) | 6 (1.22) | 82 (2.14) |

| Yeasts | 9 (0.41) | 4 (0.35) | 7 (1.43) | 20 (0.52) |

| Candida spp. | 2 (0.09) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.08) | |

| Other yeasts | 7 (0.32) | 4 (0.35) | 6 (1.22) | 17 (0.44) |

| Samples not taken | 407 (18.61) | 173 (14.94) | 80 (16.33) | 660 (17.21) |

| Others | 179 (8.18) | 61 (5.27) | 26 (5.31) | 266 (6.94) |

| D-SSI+O/S-SSI | ||||

| Gram-positive bacteria | 844 (22.94) | 603 (23.79) | 426 (27.92) | 1873 (24.2) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 311 (8.45) | 213 (8.4) | 164 (10.75) | 688 (8.89) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 154 (4.19) | 187 (7.38) | 151 (9.9) | 492 (6.36) |

| Other GPB | 188 (5.11) | 115 (4.54) | 52 (3.41) | 355 (4.59) |

| S. aureus | 94 (2.56) | 57 (2.25) | 34 (2.23) | 185 (2.39) |

| CoNS | 97 (2.64) | 31 (1.22) | 25 (1.64) | 153 (1.98) |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 1854 (50.39) | 1170 (46.15) | 621 (40.69) | 3645 (47.09) |

| Escherichia coli | 1130 (30.71) | 641 (25.29) | 293 (19.2) | 2064 (26.67) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 197 (5.35) | 146 (5.76) | 84 (5.5) | 427 (5.52) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 106 (2.88) | 98 (3.87) | 76 (4.98) | 280 (3.62) |

| Other GNB | 421 (11.44) | 285 (11.24) | 168 (11.01) | 874 (11.29) |

| Anaerobes | 170 (4.62) | 87 (3.43) | 39 (2.56) | 296 (3.82) |

| Bacteroides spp. | 66 (1.79) | 38 (1.5) | 10 (0.66) | 114 (1.47) |

| Other anaerobes | 88 (2.39) | 46 (1.81) | 22 (1.44) | 156 (2.02) |

| Yeasts | 50 (1.36) | 67 (2.64) | 82 (5.37) | 199 (2.57) |

| Candida spp. | 13 (0.35) | 20 (0.79) | 20 (1.31) | 53 (0.68) |

| Other yeasts | 37 (1.01) | 47 (1.85) | 62 (4.06) | 146 (1.89) |

| Clostridium spp. | 16 (0.43) | 3 (0.12) | 7 (0.46) | 26 (0.34) |

| Samples not taken | 450 (12.23) | 415 (16.37) | 254 (16.64) | 1119 (14.46) |

| Others | 311 (8.45) | 193 (7.61) | 104 (6.82) | 608 (7.86) |

S-SSI: superficial incisional site infection; D-SSI: deep incisional site infection; O/S-SSI: organ/space surgical site infection; CoNS: Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci; GPB: Gram-positive bacteria; GNB: Gram-negative bacteria.

On the other hand, the combined analysis of D-SSI and O/S-SSI detected that the differences between periods were more marked, with a sharp decrease in Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria in the latter period, complemented by an increase in Gram-positive cocci and fungi. There was an increase in the proportion of enterococci identification, especially Enterococcus faecium, which was isolated from 5.1% of S-SSI and from 9.9% of O/S-SSI in Period 3.

DiscussionIn this pragmatic cohort study, the VINCat surveillance programme achieved a sustained decrease in SSI rates and other adverse outcomes in elective colorectal surgery over time. In contrast to the previous reports of an immediate effect of surveillance programmes on SSI rates,4,5 this “surveillanceeffect” was slow to appear, and during the first five-year period SSI rates remained around 20% in both colon and rectal surgery.

This study again contrasts to the findings of a systematic review, which included data from four large national surveillance networks and described a “dilution” of the effect of surveillance from year 5 onwards.5 On the opposite, our second five-year period showed a solid and steady improvement in outcomes.

We believe this is probably due to the decision to move from an observational surveillance model to active, interventional surveillance, which ultimately led to the development of the first SSI prevention bundle in Period 2. In a previous analysis of the effect of this bundle, overall SSI rates ranged from 16.71% when none of the bundle measures were used to 6.23% when all six measures were applied appropriately. The application of the bundle halved the likelihood of overall SSI and O/S-SSI.12

The third five-year period reflects the cumulative effect of the colorectal-specific bundle and the multi-purpose PREVINQ-CAT bundle, which managed to maintain the fall in SSI rates, although at a slower pace. Other authors have also demonstrated the benefits of SSI preventive bundles in colorectal surgery,13,14 especially on incisional SSIs. However, in contrast to our results in colon surgery, most of the published bundles did not improve O/S-SSI rates.15,16 The pathophysiology of O/S-SSI is different from that of incisional SSI,17 due to the critical role of anastomotic leakage in its occurrence.18,19 The specific VINCat bundle was designed with the dual aim of reducing overall SSI and O/S-SSI. For the latter, mechanical bowel preparation and oral antibiotic prophylaxis were added, as in other studies.20 Nevertheless, this had no effect on O/S-SSI in rectal surgery, probably due to the higher rate of anastomotic leakage in these procedures.

It is obvious that during the period under study there have been improvements in care practices that may have acted as confounding factors in the evaluation of the specific interventions applied by the programme. These include the widespread introduction of the laparoscopic technique in colorectal surgery. Laparoscopy is known to reduce overall and incisional SSIs, although in most cases no effects on O/S SSIs have been reported.21,22 In contrast, in our series the progressive introduction of laparoscopy acted as a significant protective factor not only for overall and incisional SSI but also for O/S SSI, albeit to a lesser extent.

When, in 2018, the bundles of the PREVINQ-CAT programme were launched, the colorectal bundle was extended to 14 measures. It has been argued that, for optimal application, bundles should contain a limited number of measures.23 However, in two meta-analyses colorectal bundles containing 11 or more measures achieved the highest SSI reductions.24,25 All measures included in both bundles were adopted with an average adherence rate of 70–80% with an increase over time.

The differences in SSI rates depending on the volume and complexity of hospitals should be noted, and, above all, the variability in SSI outcomes within groups of hospitals with similar characteristics, a finding rarely discussed in other surveillance systems. Validation of the data by trained investigators, as suggested by other authors,26 did not demonstrate inter-hospital differences in the surveillance method. Other secondary outcomes such as LOS and mortality also decreased and were probably associated with the reduction in the SSI rate, in addition to the increased rate of laparoscopic surgery and other care improvements introduced during the study period.

Over the course of the surveillance period, changes in the flora isolated from SSI samples were identified, especially in D-SSI and O/S-SSI, the most clinically severe infections that most frequently require antibiotic treatment. At these sites there were falls in Gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes, in parallel with rises in Gram-positive bacteria and fungal isolates. Although the absolute figures are small, the increase in the isolation of enterococci is worth noting – especially Enterococcus faecium, which rose sharply at all three surgical sites. The increase in SSIs without microbiological samples can be explained by the increasingly frequent early diagnosis of O/S-SSI by biomarker monitoring and CT scanning, successfully treated with antibiotics, in many cases without percutaneous or surgical drainage.

Probably the main contribution of our findings is the confirmation that a surveillance network aimed at heightening “situationalawareness” of SSI rates has an effect, albeit limited, and that the implementation of targeted interventions can significantly improve outcomes. This would support the idea of the usefulness of HAI surveillance to guide decision-making and implementation of preventive interventions, as the first step before action. The evidence that epidemiological surveillance combined with the implementation of minor interventions did not achieve significant improvements in outcomes led to the planning of a more aggressive intervention with the design of the SSI prevention bundles. We think that the introduction of these high-impact interventions at multi-centre level in such a short time was only possible thanks to the consolidated surveillance system established by VINCat.

Indeed, the success of a surveillance system depends on the quality of the data it provides, which in turn is linked to the presence of highly trained infection control teams in each hospital, strong coordination between hospitals, a homogeneous surveillance methodology and regular auditing of the results.26 We believe that the successive interventions applied to the surveillance programme – namely, the formation of a multidisciplinary coordination group, the separation of colon and rectal data, and the implementation of the preventive bundles – were the key to the improved results.

Above all, a successful infection surveillance network requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving a wide range of specialities with the same objective. In this case, the commitment of the ICTs, infectious disease specialists and microbiologists, together with perioperative nursing teams, anaesthesiologists and colorectal surgeons was vital in the development of the programme and the design of interventions that have proven to be successful.

Limitations and strengths. Due to the length of time studied, the results may reflect the effect of changes in surgical practice and in the organisation of the health care system. Secondly, as in other surveillance databases, the number of variables collected was restricted, and some valuable factors such as body mass index, diabetes and smoking were not assessed. Furthermore, due to the descriptive nature of the study and the lack of adjustment for confounding variables, the presented ORs are unadjusted and do not reflect a causal relationship. Finally, self-reported data can be a potential source of bias, although several validation actions were carried out to mitigate this issue.

This study also has several strengths. It is grounded on a large population and a high volume of cases followed up in accordance with a consolidated, audited, and reviewed reporting method. Although the programme is based on voluntary hospital participation, almost all public hospitals in the area and several private institutions were included. We believe that the inclusion of different types and sizes of hospital may make the results generalisable to other settings.

ConclusionsThe detailed analysis of postoperative infection rates in colorectal surgery allows the design of preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of SSI. An interventional surveillance programme achieved a significant reduction in SSI rates in colorectal surgery over a 15-year period.

FundingThe VINCat Programme is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this article. All authors submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and the conflicts that the editors consider relevant to this work are disclosed here.

The authors thank the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support, and all nurses and physicians at the participating hospitals involved in reporting their infection data.

Dolors Castellana and Elisa Montiu González, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida; Graciano García Pardo and Francesc Feliu Villaró, Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona; Josep Rebull Fatsini and M. France Domènech Spaneda, Hospital Verge de la Cinta de Tortosa; Marta Conde Galí and Anna Oller Pérez-Hita, Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta Girona; Lydia Martín and Ana Lerida, Hospital de Viladecans; Sebastiano Biondo and Emilio Jiménez Martínez, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge; Nieves Sopena Galindo and Ignasi Camps Ausàs, Hospital Universitari Germans Tries i Pujol; Carmen Ferrer and Luis Salas, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Rafael Pérez Vidal and Dolors Mas Rubio, Althaia Xarxa Assistencial de Manresa; Irene García de la Red, Hospital HM Delfos; Mª Angels Iruela Castillo and Eva Palau i Gil, Clínica Girona; José Antonio Martínez Martínez and Mª Blanca Torralbo Navarro, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona; Maria López and Carol Porta, Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa; Alex Smithson Amat and Guillen Vidal Escudero, Fundació Hospital de l’Esperit Sant; José Carlos de la Fuente Redondo and Montse Rovira Espés, Hospital Comarcal Mora d’Ebre; Arantxa Mera Fidalgo and Luis Escudero Almazán, Hospital de Palamós; Susanna Camps Carmona, Hospital Parc Taulí de Sabadell; Vicens Diaz-Brito and Mª Carmen Álvarez Moya, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu – Hospital de Sant Boi; Laura Grau Palafox and Yésika Angulo Gómez, Hospital de Terrassa; Anna Besolí Codina and Carme Autet Ricard, Consorci Hospitalari de Vic; Carlota Hidalgo López, Hospital del Mar; Elisabeth Lerma-Chippirraz and Demelsa Mª Maldonado López, Hospital General de Granollers; David Blancas and Esther Moreno Rubio, Consorci Sanitari del Garraf; Roser Ferrer i Aguilera, Hospital Sant Jaume de Calella; Simona Iftimie Iftimie and Antoni Castro-Salomó, Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus; Rosa Laplace Enguídanos and Maria Carmen Sabidó Serra, Hospital de Sant Pau i Santa Tecla; Núria Bosch Ros, Hospital de Santa Caterina; Virginia Pomar Solchaga, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Laura Lázaro Garcia and Angeles Boleko Ribas, Hospital Universitari Quirón Dexeus; Jordi Palacín Luque and Alexandra Lucía Moise, Pius Hospital de Valls; Mª Carmen Fernández Palomares and Santiago Barba Sopeña, Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor; Eduardo Sáez Huertas and Sara Burges Estada, Clínica NovAliança; Josep María Tricas Leris and Eva Redon Ruiz, Fundació privada Hospital de Mollet; Montse Brugués Brugués and Susana Otero Acedo, Consorci Sanitari de l’Anoia. Igualada; Maria Cuscó Esteve and Lourdes Gabarró, Hospital Comarcal de l’Alt Penedès; Fco. José Vargas-Machuca and Mª de Gracia García Ramírez, Centre MQ de Reus; Elena Vidal Díez and Oscar Estrada Ferrer, Consorci Hospitalari del Maresme. Hospital de Mataró; Mariló Marimón Morón and Marisol Martínez Sáez, Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya; Josep Farguell and Mireia Saballs, QUIRON Salud; Montserrat Vaqué Franco and Leonor Invernón Garcia, Hospital de Barcelona; Rosa Laplace Enguídanos and Meritxell Guillemat Marrugat, Hospital Comarcal del Vendrell; Ana Coloma Conde, Hospital Moisès Broggi.