The VINCat Program: a 19-year model of success in infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, Spain

Más datosCatheter-related bacteremia (CRB) is one of the most frequent infections acquired during hospitalization. We summarize the results of CRB surveillance conducted by the Catalan Program of Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections (VINCat) over the past fifteen years.

MethodsAll episodes of hospital-acquired CRB diagnosed in the 55 Catalan hospitals participating in the VINCat program (2008–2023) were recorded. Annual incidence rates per 1000 patient-days were calculated. Analyses were stratified into three relevant five-year periods: 2008–2012, 2013–2017, and 2018–2022. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were used to compare infection rates.

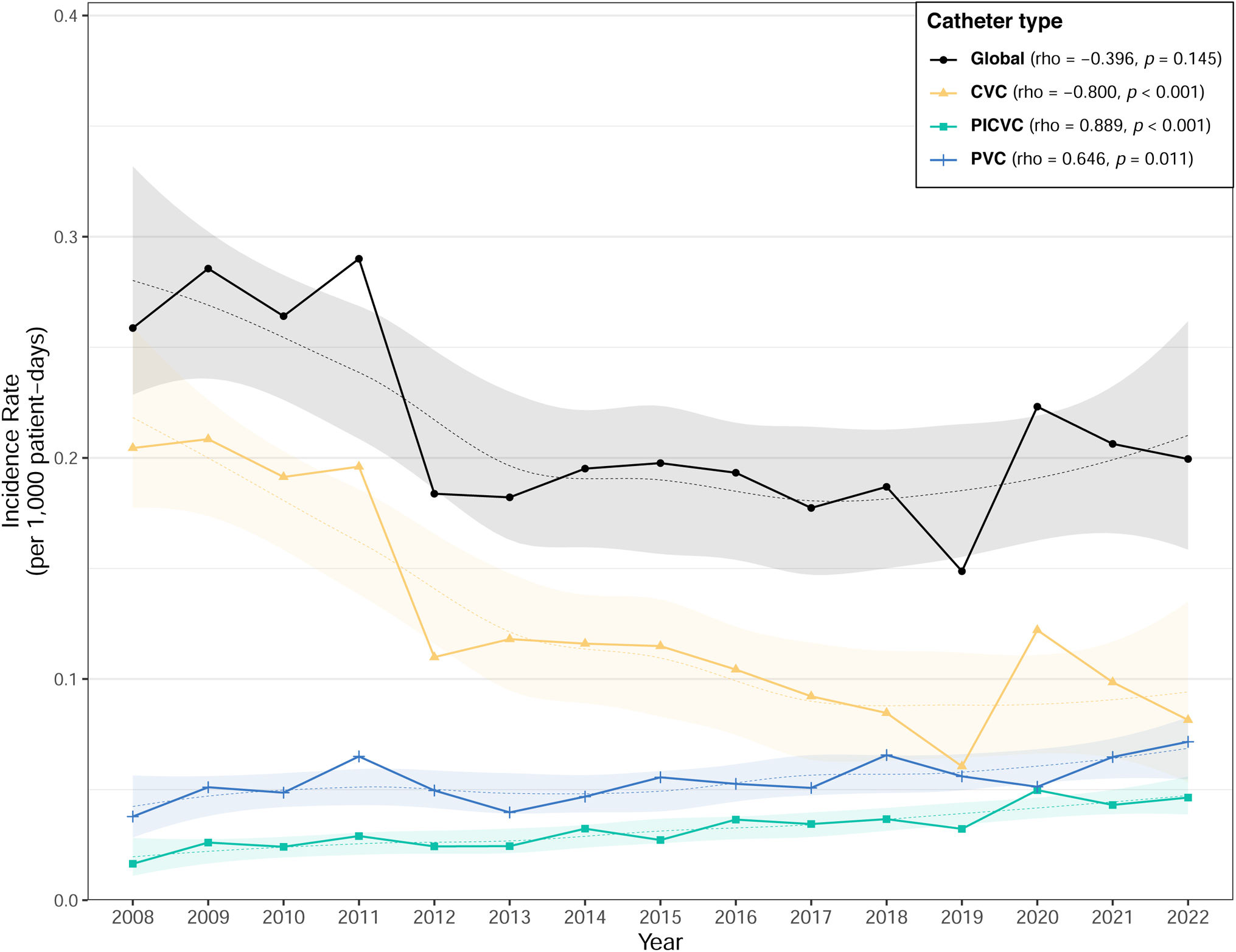

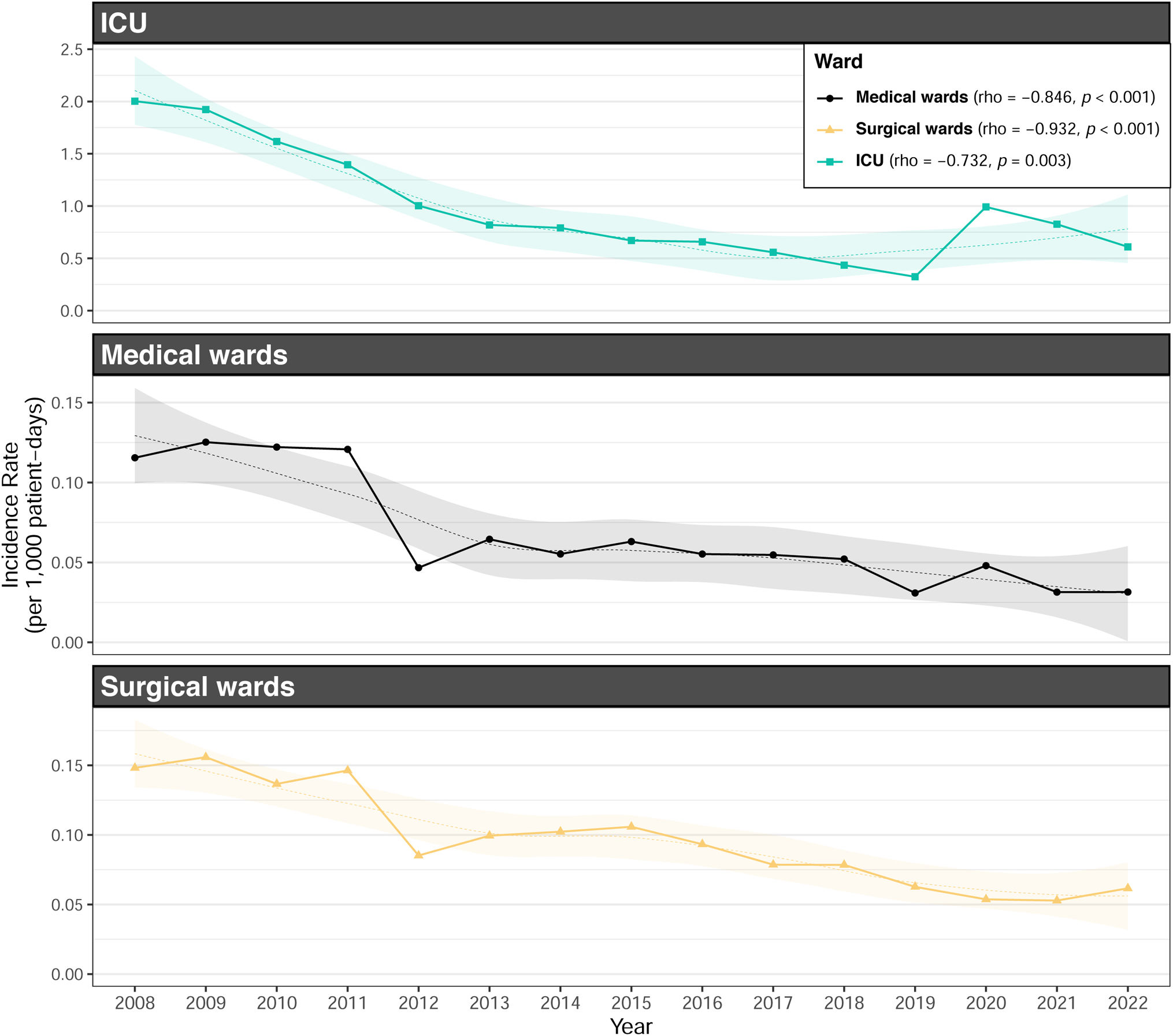

ResultsDuring the study period, 10,212 episodes of nosocomial CRB were diagnosed. The global incidence rate was 0.21 episodes per 1000 patient-days (intensive care units (ICUs): 1.13; medical wards: 0.16; surgical wards: 0.15). Gram-positive bacteria caused 68.3% of the episodes. The incidence rate of CRB acquired in ICUs and that of CRB associated with central venous catheters decreased during the study period, while episodes associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVCs) and peripherally-inserted central venous catheters (PICVCs) significantly increased (p<0.001).

ConclusionsThe current study underscores the necessity for interventional programs targeting PVCs, particularly in non-ICU wards.

La bacteriemia relacionada con catéter (BRC) es una de las infecciones más frecuentes adquiridas durante la hospitalización. Se resumen los resultados de la vigilancia de la BRC llevada a cabo por el Programa Catalán de Vigilancia de las Infecciones Nosocomiales (VINCat) durante los últimos 15 años.

MétodosSe registraron todos los episodios de BRC de adquisición hospitalaria diagnosticados en los 55 hospitales catalanes participantes en el programa VINCat (2008-2023). Se calcularon las tasas de incidencia anuales por 1.000 pacientes/día. Los análisis se estratificaron en 3 periodos relevantes: 2008-2012, 2013-2017 y 2018-2022. Se utilizaron razones de densidad de incidencia (RDI) para comparar las tasas de infección.

ResultadosDurante el período de estudio, se diagnosticaron 10.212 episodios de BRC nosocomial. La tasa de incidencia global fue de 0,21 episodios por 1.000 pacientes/día (unidades de cuidados intensivos [UCI]: 1,13; salas médicas: 0,16; salas quirúrgicas: 0,15). Las bacterias grampositivas causaron el 68,3% de los episodios. La tasa de incidencia de BRC adquirida en la UCI y la de BRC asociada a catéteres venosos centrales disminuyeron durante el periodo de estudio, mientras que los episodios asociados a catéteres venosos periféricos (CVP) y catéteres venosos centrales de inserción periférica (CVCIP) aumentaron significativamente (p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl presente estudio subraya la necesidad de programas de intervención dirigidos a los CVP, especialmente en las salas que no pertenecen a la UCI.

Catheter-related bacteremia (CRB) is a frequent infection that accounts for approximately 12% of all healthcare-associated infections (HAIs)1 and 25% of all nosocomial bloodstream infections.2 Incidence rates can vary depending on various factors, including the type of catheter, the patient population, and the healthcare setting. Patients with central venous catheters (CVCs) are at increased risk, as central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) incidence rate can range from 0.1 to 5.1 infections per 1000 catheter-days.1,3–5

CRB can cause significant clinical consequences, including sepsis, endocarditis, and organ dysfunction, leading to prolonged hospital stays, increased mortality rates, and soaring healthcare costs. Patients with CRB have a three-fold increase in mortality compared to those without.6 Moreover, the economic burden of CRB is substantial. It was estimated that each CRB case added an average of $45,814 to hospital costs.7 These expenses encompass not only extended hospitalization but also increased antibiotic usage and additional diagnostic procedures.

Preventing CRB is paramount. Strict adherence to catheter insertion and maintenance protocols, regular assessment of catheter necessity, and utilizing appropriate materials for each situation have shown efficacy in reducing infection rates.4,8 Also, in recent years, chlorhexidine dressings8 and antimicrobial-coated catheters9 have shown promise in reducing CLABSI incidence rates.

A trial led by Dr. Peter Pronovost and collaborators, published in 2008, demonstrated the profound impact of a bundled intervention in preventing CRB within intensive care units (ICUs).10 The study introduced a simple yet effective checklist-based intervention that encompassed hand hygiene, maximal barrier precautions during catheter insertion, chlorhexidine skin antisepsis, avoidance of the femoral site, and daily review of catheter necessity. This groundbreaking trial showcased a remarkable 66% reduction in CRB rates, highlighting the effectiveness of systematic, evidence-based interventions in healthcare settings.

Since CRB poses a significant threat to patient safety in healthcare settings, national surveillance programs such as National Healthcare Safety Network3 in the United States, National Healthcare-Associated Infections Surveillance System in Canada,11 the National Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the United Kingdom12 or the National Healthcare Safety Network in Australia13 have been developed around the world. These national surveillance programs rely on standardized definitions and reporting criteria, allowing for consistent data collection and analysis. The data collected not only help identify infection trends but also guide the development and evaluation of infection prevention strategies.

By the time the Catalan Programme for the Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections (VINCat) was established in 2008, a total of 692 episodes of catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRB) had been diagnosed in our region. The incidence of CRB was approximately 0.29 episodes per 1000 hospital stays, compared to 2.33 episodes per 1000 hospital stays across all Catalan intensive care units.14 VINCat thus represented a necessary healthcare initiative dedicated to the monitoring and prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), with a particular focus on CRB.

The primary aim of this review is to examine the surveillance of CRB over the past fifteen years, to assess changes in CRB incidence rates, and to explore trends in the epidemiology of this HAI. Finally, we seek to identify the most significant insights and lessons gained from our experience in this area.

MethodsMethodology has previously described elsewhere.14 Briefly, all detected hospital-acquired episodes of CRB, diagnosed in adult patients at each of the participating hospitals are reported to the VINCat program by the infection control teams. The detection of CRB is based on the daily evaluation of all patients with positive blood cultures.

SettingThe 55 Catalan hospitals participating in the VINCat program are classified into three categories according to complexity and number of beds available for hospitalization: 500 beds or more (Group I), 200–499 beds (Group II), and fewer than 200 beds (Group III).

Data from each hospital are continuously monitored. The annual incidence rates are compared with the hospitals’ records from previous years, and with the aggregate data compiled in the VINCat program.

DefinitionsA bloodstream infection in a patient using a venous catheter is defined as a CRB if it accomplishes the following criteria: The causing microorganism must be detected in at least one set of blood cultures obtained from a peripheral vein and, in the case of habitual skin-colonising microorganisms (coagulase-negative staphylococci [CoNS], Micrococcus spp., Propionibacterium acnes, Bacillus spp. and Corynebacterium spp.), in two sets. These cultures must be associated with clinical manifestations of infection (fever>37.5°C, chills and/or hypotension) and the absence of any apparent alternative source of BRC.

These conditions must be accompanied by one or more of the following:

- (i)

semiquantitative culture of catheter tip (>15colony forming units [CFU] per catheter segment) or quantitative culture (>103CFU per catheter segment), with detection of the same microorganism as in blood cultures obtained from the peripheral blood;

- (ii)

quantitative blood cultures with detection of the same microorganism, with a difference of 5:1 or greater between the blood obtained from any of the lumens of a venous catheter and that obtained from a peripheral vein by puncture;

- (iii)

difference in time to positivity of the blood cultures of above 2h between cultures obtained from a peripheral vein and from the lumen of a venous catheter;

- (iv)

presence of inflammatory signs or purulent secretions in the insertion point or the subcutaneous tunnel of a venous catheter. A culture of the secretion showing growth of the same microorganism as the one detected in the blood cultures is also recommended (but not obligatory).

Episodes in the following patients were not included in the study: patients up to 18 years of age; outpatients with a hospital stay of less than 48h at time of BSI detection; patients in whom CRB was detected at an outpatient service; CRB associated with arterial catheters.

Statistical analysisThe data were summarized using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. For continuous variables, we presented medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviations, depending on the distribution. The annual incidence rate of CLABSI was obtained by dividing the total number of episodes of CRB with the total number of patient days in 1 year and this is then adjusted for 1000 patient-days to give the annual incidence rate of CRB diagnosed per 1000 patient-days. The study period was stratified into three relevant time five-year periods: 2008–2012, 2013–2017, 2018–2022 to enhance consistency throughout the analysis.

To assess differences in percentages, we conducted chi-square tests or Fisher's tests, as deemed suitable. For continuous variables, comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test, as appropriate. For comparisons of incidence rates, we chose the incidence rate ratio (IRR) to compare infection rates between the last two periods due to its recent clinical and epidemiological relevance. This choice allows us to identify significant changes and provide useful data for current interventions. To evaluate the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between CRB incidence rates over the years, we performed a Spearman correlation (rho). A significance level of 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests. Additionally, LOESS smoothing was applied to the graphs to enhance the clarity in depicting data trends. The results were analyzed using the R statistical software version 4.2.2, developed by The R Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

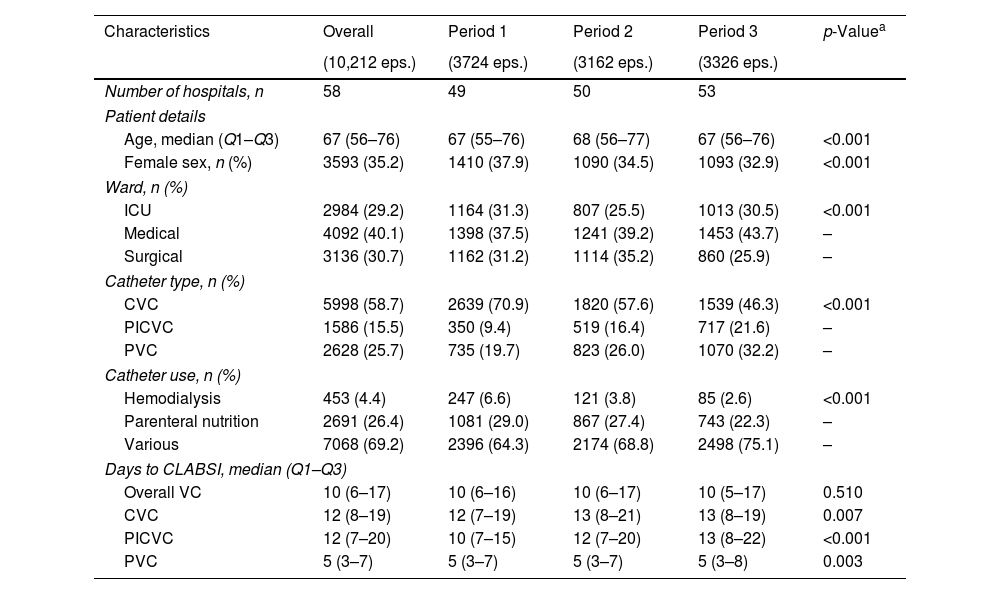

ResultsDuring the study period of 15 years (2008–2022), 10,212 episodes of nosocomial CRB were diagnosed (Table 1). As a result, a global incidence rate of 0.21 episodes per 1000 patient-days was observed (Table 2). Almost 60% of CRB episodes were related to a CVC (incidence 0.12 episodes per 1000 patient-days), while 25.7% and 15.5% were related to peripheral venous catheter (PVC) (0.05 episodes per 1000 patient-days) and peripherally inserted central venous catheter (PICVC) (0.03 episodes per 1000 patient-days). Median time from catheter insertion to CRB was 12 days (CVC), 12 days (PICVC) and 5 days (PVC), respectively. Most episodes were originated in catheters used for neither hemodialysis (4.4%) nor parenteral nutrition (26.4%).

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with catheter-related bacteremia stratifying by five-year periods.

| Characteristics | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10,212 eps.) | (3724 eps.) | (3162 eps.) | (3326 eps.) | ||

| Number of hospitals, n | 58 | 49 | 50 | 53 | |

| Patient details | |||||

| Age, median (Q1–Q3) | 67 (56–76) | 67 (55–76) | 68 (56–77) | 67 (56–76) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 3593 (35.2) | 1410 (37.9) | 1090 (34.5) | 1093 (32.9) | <0.001 |

| Ward, n (%) | |||||

| ICU | 2984 (29.2) | 1164 (31.3) | 807 (25.5) | 1013 (30.5) | <0.001 |

| Medical | 4092 (40.1) | 1398 (37.5) | 1241 (39.2) | 1453 (43.7) | – |

| Surgical | 3136 (30.7) | 1162 (31.2) | 1114 (35.2) | 860 (25.9) | – |

| Catheter type, n (%) | |||||

| CVC | 5998 (58.7) | 2639 (70.9) | 1820 (57.6) | 1539 (46.3) | <0.001 |

| PICVC | 1586 (15.5) | 350 (9.4) | 519 (16.4) | 717 (21.6) | – |

| PVC | 2628 (25.7) | 735 (19.7) | 823 (26.0) | 1070 (32.2) | – |

| Catheter use, n (%) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | 453 (4.4) | 247 (6.6) | 121 (3.8) | 85 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 2691 (26.4) | 1081 (29.0) | 867 (27.4) | 743 (22.3) | – |

| Various | 7068 (69.2) | 2396 (64.3) | 2174 (68.8) | 2498 (75.1) | – |

| Days to CLABSI, median (Q1–Q3) | |||||

| Overall VC | 10 (6–17) | 10 (6–16) | 10 (6–17) | 10 (5–17) | 0.510 |

| CVC | 12 (8–19) | 12 (7–19) | 13 (8–21) | 13 (8–19) | 0.007 |

| PICVC | 12 (7–20) | 10 (7–15) | 12 (7–20) | 13 (8–22) | <0.001 |

| PVC | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–8) | 0.003 |

ICU: intensive care unit; VC: venous catheter; CVC: central venous catheter; PVC: peripheral venous catheter; PICVC: peripherally inserted central venous catheter; CLABSI: central line-associated bloodstream infection.

Incidence of catheter-related bacteremia stratifying by admission unit and type of catheter divided by five-year periods.

| Ward/catheter type | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Crude IRRa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10,212 eps.) | (3724 eps.) | (3162 eps.) | (3326 eps.) | ||

| Global | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

| Number of patient-days | 48,585,432 | 14,586,142 | 16,715,688 | 17,283,602 | – |

| CVC | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.82 (0.76–0.88)* |

| PICVC | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1.34 (1.19–1.50)* |

| PVC | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 1.26 (1.15–1.38)* |

| Medical wards | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) |

| Number of patient-days | 25,080,943 | 7,595,243 | 8,331,001 | 9,154,699 | – |

| CVC | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.66 (0.58–0.76)* |

| PICVC | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.46 (1.21–1.76)* |

| PVC | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 1.29 (1.16–1.43)* |

| Surgical wards | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.83 (0.76–0.90)* |

| Number of patient-days | 20,860,614 | 6,350,552 | 7,501,802 | 7,008,260 | – |

| CVC | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.65 (0.58–0.73)* |

| PICVC | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.24 (1.02–1.50)* |

| PVC | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) |

| ICU | 1.13 | 1.82 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) |

| Number of patient-days | 2,643,874 | 640,347 | 882,884 | 1,120,643 | – |

| CVC | 0.89 | 1.55 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) |

| PICVC | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.12 (0.90–1.39) |

| PVC | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.00 (0.69–1.43) |

ICU: intensive care unit; VC: venous catheter; CVC: central venous catheter; PVC: peripheral venous catheter; PICVC: peripherally inserted central venous catheter; IRR: incidence rate ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Although medical wards accounted for most of the diagnosed episodes (40.1%, compared with 29.2% in surgical wards and 30.7% in intensive care units), incidence rate was higher in intensive care wards (1.13 vs 0.16 and 0.15) (Table 2). The IRR comparing periods 2 (reference) and 3 did not show a statistically significant change for ICU wards (IRR 0.99, 95% CI 0.90–1.08). However, surgical wards exhibited a significant decrease in incidence (IRR 0.83, 95% CI 0.76–0.90, p<0.05) (Table 2).

Gram-positive bacteria caused 68.3% episodes, being coagulase-negative staphylococci the most frequent (37.8%), followed by Staphylococcus aureus (24%). Among Gram-negative bacilli, Klebsiella pneumoniae (7.1%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5.3%) were the most frequent. Last, 6.0% were caused by yeasts (Table 3).

Etiology of microorganisms causing catheter-related bacteremia stratifying by five-year periods.

| Family/microorganism | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10,212 eps.) | (3724 eps.) | (3162 eps.) | (3326 eps.) | ||

| Gram-positive bacteria | 7346 (68.27) | 2632 (66.21) | 2225 (66.80) | 2489 (72.04) | <0.001 |

| CoNS | 4063 (37.76) | 1553 (39.07) | 1228 (36.87) | 1282 (37.11) | 0.011 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2580 (23.98) | 814 (20.48) | 801 (24.05) | 965 (27.93) | <0.001 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 450 (4.18) | 177 (4.45) | 113 (3.39) | 160 (4.63) | 0.023 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 184 (1.71) | 60 (1.51) | 66 (1.98) | 58 (1.68) | 0.319 |

| Other GPB | 69 (0.64) | 28 (0.70) | 17 (0.51) | 24 (0.69) | 0.516 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 2619 (24.34) | 1033 (25.99) | 863 (25.91) | 723 (20.93) | <0.001 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 759 (7.05) | 285 (7.17) | 262 (7.87) | 212 (6.14) | 0.011 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 574 (5.33) | 226 (5.69) | 195 (5.85) | 153 (4.43) | 0.008 |

| Escherichia coli | 234 (2.17) | 107 (2.69) | 77 (2.31) | 50 (1.45) | <0.001 |

| Other GNB | 1052 (9.78) | 415 (10.44) | 329 (9.88) | 308 (8.91) | 0.033 |

| Yeasts | 646 (6.00) | 236 (5.94) | 209 (6.27) | 201 (5.82) | 0.644 |

| Candida spp. | 291 (2.7) | 95 (2.39) | 87 (2.61) | 109 (3.15) | 0.173 |

| Others yeasts | 355 (3.3) | 141 (3.55) | 122 (3.66) | 92 (2.66) | 0.024 |

| Anaerobes | 7 (0.07) | 2 (0.05) | 3 (0.09) | 2 (0.06) | 0.612 |

| Bacteroides spp. | 3 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 1.000 |

| Clostridium spp. | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.03) | 0 (0.00) | 1.000 |

| Other anaerobes | 3 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 1.000 |

| Others | 142 (1.32) | 71 (1.79) | 31 (0.93) | 40 (1.16) | 0.003 |

CoNS: coagulase-negative Staphylococci; GPB: gram-positive bacteria; GNB: gram-negative bacteria.

Incidence rate of CRB associated to CVC decreased during the study period (p<0.001), while that associated to PICVC increased (p<0.001) (Fig. 1). This downward trend was observed both globally and in the three types of hospital wards (medical, surgical and intensive care units) (Fig. 2). Incidence rate of episodes associated with PVC increased in both medical wards and intensive care units, and BRC-PICVC incidence rates increased in medical and surgical wards (Table 2).

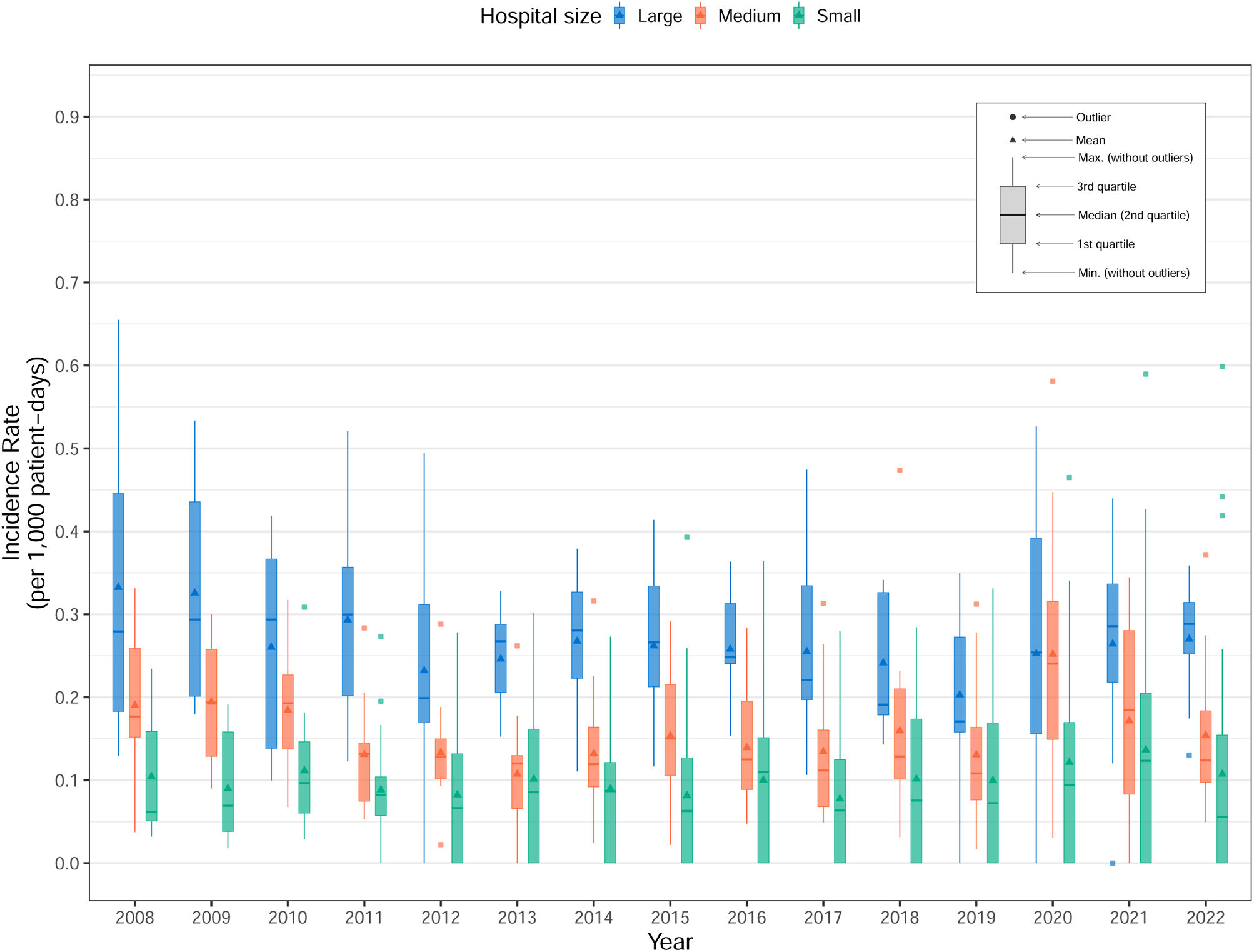

Stratifying by hospital size (Table 4, Fig. 3), CVC associated episodes decreased significantly in larger hospitals when comparing period 3 with period 2 (IRR 0.68, 95% CI 0.62–0.74, p<0.05). In contrast, medium-sized and smaller hospitals showed increases in the incidence of CRB associated with the three catheter types during the same comparison. Specifically, in medium-sized hospitals, significant increases were observed for PICVC (IRR 2.07, 95% CI 1.66–2.58, p<0.05) and PVC (IRR 1.27, 95% CI 1.08–1.49, p<0.05). Similarly, smaller hospitals experienced significant increases for PICVC (IRR 1.73, 95% CI 1.13–2.70, p<0.05) and PVC (IRR 1.66, 95% CI 1.38–2.00, p<0.05). Regarding the causing microorganisms, Gram-positive bacteria increased in the study period, contrary to what was observed with Gram-negative bacteria (Table 3).

Incidence rate per 1000 patient-days of catheter-related bacteremia stratifying by hospital size, and catheter type.

| CVC | PICVC | PVC | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital size | OP | P1 | P2 | P3 | cIRRa (95% CI) | OP | P1 | P2 | P3 | cIRRa (95% CI) | OP | P1 | P2 | P3 | cIRRa (95% CI) |

| Large | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.68 (0.62–0.74)* | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 1.08 (0.94–1.24) | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.07 (0.94–1.23) |

| Medium | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 1.14 (1.01–1.29)* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 2.07 (1.66–2.58)* | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 1.27 (1.08–1.49)* |

| Small | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.94 (0.76–1.16) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.73 (1.13–2.70)* | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 1.66 (1.38–2.00)* |

CVC: central venous catheter; PVC: peripheral venous catheter; PICVC: peripherally inserted central venous catheter; OP: overall period; P1: period 1 (2008–2012); P2: period 2 (2013–2017); P3: period 3 (2018–2022); cIRR: crude incidence rate ratio; CI: confidence interval.

This manuscript is a report of the CRB surveillance performed along 15 years in Catalonia. VINCat national surveillance program recompiled data from all the episodes of CRB, acquired in hospital setting, regardless of the catheter type and the unit of acquisition.15 This is probably, one of our program most significative characteristics, since peripherally inserted catheters have usually been neglected by most surveillance programs, being CLABSI surveillance their target.16 The decision to include all catheter types was taken with the convincement that peripherally inserted catheters were the most frequently used in healthcare setting and the most frequently involved in catheter failure and related infections, as more recently has been consistently remarked along the last years.17,18

Therefore, our surveillance program allows to describe the incidence increase of CRB associated with peripherally inserted catheters concomitantly to the downward trend observed in CVC CRB.

This differentiated behavior in the evolution of CRB associated with CVC and PVC can be explained by the much higher frequency of peripheral venous catheter use compared to CVC, its insertion in emergency facilities, as well as the disparity in adherence to preventive measures in both cases, during catheter insertion and maintenance.19

The downward trend in CVC-related CRB incidence observed over these fifteen years may be attributed to three primary factors. Firstly, the implementation of coordinated surveillance at each hospital, along with benchmarking of CRB rates between centers, has been associated with a decrease in nosocomial infection rates, as recently observed.20 Secondly, nearly all hospitals implemented “bacteremia zero” programs in their intensive care units, following the approach published by Pronovost and colleagues,10 in which a bundle of preventive measures significantly impacted CRB rates. Specifically, this intervention included proper hand hygiene, the use of chlorhexidine-alcohol solution for skin antisepsis, full barrier precautions, daily assessment of the need for catheterisation, and avoidance of the femoral site. Lastly, CRB associated with PVC and CVC in the general hospital wards of 11 Catalan hospitals was specifically monitored in 2010.21 The intervention consisted of implementing a bundle of best practices during catheter insertion and maintenance, along with a training program for healthcare providers, conducting four point-prevalence surveys, and providing feedback reports to the staff involved. The study included both central (CVC) and peripheral venous catheters (PVCs) and a decrease in CVC-associated CRB – but no in PVC CRB – was observed over the study period.

Notably, global incidence rate in intensive care units decreased until 2020, when it was observed a massive disruption of COVID19 pandemic in hospitals and lack of universal accomplishment of preventive measures, which had been appropriately implemented in previous years. During this period, the incidence rate of CRB was expected to increase by 1.07 (95% CI 1–1.15) for every 1000 COVID-19-related hospital admissions, particularly in intensive care units, where observed rates increased to 3.42 times the expected levels.22

In contrast to the VINCat program, other surveillance systems monitor only catheter-related bloodstream infections associated with central venous catheters and use the indicator “cases per 1000 catheter days.” Reported rates range from 0.5 to 2 cases per 1000 catheter days in adult ICUs, while in conventional units, they vary between 0.2 and 1 case per 1000 catheter days (2019–2020).3 The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (HAI-Net – Europe) reports CVC-associated bloodstream infection rates in European ICUs ranging from 1 to 2.5 cases per 1000 catheter days (2018–2021).11 Finally, in Spain, the reported rate of central line-associated bloodstream infections in adult ICUs and conventional units since the implementation of the “Zero Infection” program is between 0.3 and 1 case per 1000 catheter days, reflecting a considerable improvement in the control of these infections at the national level.23

Regarding the episode's etiology, the observed Gram-negative bacteria downward trend might be associated with the mentioned decrease of episodes diagnosed in ICUs, especially those associated with CVC. However, these microorganisms still cause one fifth of the episodes diagnosed at our area and must be empirically covered in patients with risk factors such as femoral insertion site, long-term vascular catheters, or neutropenic patients.24

The analysis of all the compiled data during these years, allows to process the future objectives of the interventions needed to improve the incidence rates at our hospitals. Looking at the median time until BRC, it can be hypothesized that a greater effort in maintenance (and not only in catheter insertion) is needed to improve BRC rates. Therefore, some of the measures that could have the greatest impact on the incidence of CRB associated with peripheral catheters include selecting the appropriate catheter based on specific indications and anticipated duration, ensuring proper skin disinfection and the use of aseptic techniques during insertion, employing semi-permeable transparent dressings to facilitate daily inspection of the insertion site and retreat of dispensable ones might be the cornerstone of any intervention to reduce BRC taxes.25 Also, appropriate ports disinfection and use of different gadgets as neutral pressure bioconnectors -instead of three-step keys – or caps and lines provided with antimicrobial barriers are some additional measures that may have positive impact.25

The primary limitation of this study is the absence of clinical information regarding the presence of chronic illnesses or other health conditions that could have affected the risk of CRB. This information may assist in identifying the most vulnerable populations in each hospital ward, determining specific risk factors, and implementing targeted preventive measures. Furthermore, CRB incidence rates were adjusted based on patient days rather than catheter days. Adjusting based on catheter days would likely be more appropriate, as it would allow estimation based on catheter use rather than the number of patients at risk. However, it would be impractical to monitor all types of catheters inserted across various hospital wards, not just in ICUs. Additionally, due to the multicentre nature of the study, the interventions and control programs may not have been consistent across all hospitals. The exact information regarding the specific preventive measures at each hospital would be valuable for interpreting the impact of each measure. To mitigate this limitation, the VINCat program strives to standardize definitions and preventive measures. Moreover, the reported data undergo annual audits, and any deviations are reviewed in collaboration with the responsible individual at each center. However, this surveillance program has allowed us to monitor the evolving epidemiology of CRB, which continues to be a significant healthcare-associated infection. The current study underscores the necessity for interventional programs targeting PVCs, particularly in non-ICU wards. In this regard, a project to reduce CRB in conventional wards is being implemented in some hospitals participating in VINCat program (Spanish Ministry of Economics and Competitiveness. Carlos II Institute Expedient: PI20/01563). The impact of this project will be soon reported.

FundingThe VINCat Program is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest

Data availability statementRestrictions apply to the availability of these data, which belong to a national database and are not publicly available. Data was obtained from VINCat and are only available with the permission of the VINCat Technical Committee.

Significant parts of the results have already been published in Badia-Cebada et al. Euro Surveill. 2022 May;27(19):2100610. And received the permission of Eurosurveillance Journal for the publishing in this special issue of Enf Infec Microb Clin. All named authors are appropriate co-authors, and have seen and agreed to the submitted version of the paper.

A significant part of the results reported in this manuscript have already been published in: Badia-Cebada et al. Euro Surveill. 2022 May;27(19):2100610. With the permission of Eurosurveillance Journal, we have included these results in this special issue of Enf Infec Microb Clin, focused on the 15 years of the VINCat program.

Clara Sala Jofre, Consorci Sanitari Integral. Hospital Dos de Maig; Encarna Moreno Castañeda and Vicens Diaz-Brito Fernandez, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan De Déu. Hospital de Sant Boi; MªTeresa Ros Prat, Fundació Sant Hospital La Seu d’Urgell; Dolors Castellana Perelló and María Ramirez Hidalgo, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida; Graciano Garcia Pardo and Montserrat Olona Cabases, Hospital universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona; Mireia Duch Pedret and Anibal Calderon Collantes, Badalona Serveis Assistencials; Silvia Alvarez Viciana and Esther Calbo Sebastian, Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa; Esther Moreno Rubio and David Blancas Altabella, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedes i Garraf. Hospital Sant Camil; Marilo Marimon Moron and Roger Malo Barres, Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya; Alejandro Smithson Amat, Fundació Hospital de l’Esperit Sant; Mª de Gracia García Ramírez, Francisco José Vargas and Machuca Fernández, Centre MQ Reus; Mª Carmen Eito Navasal and Ana Jiménez Zárate, Institut Català d’Oncologia L’Hospitalet de Llobregat; Laura Cabrera Jaime and Ana Jiménez Zárate, Institut Català d’Oncologia Badalona; Jessica Rodríguez Garcia and Ana Jiménez Zárate, Institut Català d’Oncologia Girona; Eduardo Sáez Huerta, Clínica NovAliança de Lleida; Anna Martinez Sibat, Hospital de Campdevànol; Marta Lora Diez and Ricardo Gabriel Zules Oña, Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta Girona; Cinta Casanova Moreno and Manel Panisello Bertomeu, Hospital comarcal d’Amposta; Laura Grau Palafox, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa; Laura Arias Acedo and Mariona Secanell Espluga, Institut Guttmann; Rosa Laplace Enguídanos, Csaba Feher and Alexander Cordoba Castro, Hospital Del Vendrell; Maria Ramirez Hidalgo and Alba Guitard Quer, Hospital Universitari Santa Maria; Patricia Aguilera Diaz and Anna Besoli Codina, Consorci hospitalari de Vic; Ana Felisa Lopez Azcona and Simona Iftimie Iftimie, Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus; Mª Angels Pages Roura and Maria de la Roca Toda Savall, Hospital de Palamós; Dolors Rodríguez-Pardo, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Pilar de la Cruz Sole, Hospital Universitari Dexeus; Marta Milián Sanz, Hospital Pius de Valls; Mercè Clarós Ferret and Irene Sánchez Rodriguez, Hospital Sant Rafael; Cristina Guillaumes Bosch and Maria Alba Serra Juhé, Hospital d’Olot Comarcal de la Garrotxa; Yolanda Meije Castillo, Hospital de Bercelona.SCIAS; Clàudia MIralles Adell and José Carlos de la Fuente Redondo, Hospital Comarcal de Móra d’Ebre; Elena Chamarro Martí and Josep Rebull Fatsini, Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta; Ana Coloma Conde and Lucrecia López Gonzalez, Consorci Sanitari Integral. Hospital Universitari Sant Joan Despi. Moises Broggi; Judit Santamaria Rodriguez and Montse Brugues Bruges, Consorci Sanitari de l’Anoia. Hospital d’Igualada; Pepi Serrats Collell and Eva Palau Gil, Clinica Girona; Demelza Maldonado López, Pilar Marzuelo Fuste and Elisabet Lerma Chippirraz, Hospital General de Granollers; David Pineda Fernández and Mª Rosa Coll Colell, Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor; Josep Farguell Carreras and Mireia Saballs Nadal, Hospital QuironSalud Barcelona; Oscar del Rio Perez and Angels Garcia Flores, Hospital Sant Jaume de Calella; Carme Gallés Pacareu and Angels Garcia Flores, Hospital Comarcal de Blanes; Milagro Montero, Carlota Hidalgo López and Juan Pablo Horcajada Gallego, Hoapital del Mar; Núria Bosch Ros, Hospital Sta. Caterina Girona; Joan Carles Gisbert Cases and Teresa Domenech Forcadell, Clinica Terres de l’Ebre; María Cuscó Esteve and Laura Linares Gonzalez, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedes i Garraf. Hospital Alt Penedés; Grethel Rodríguez Cabalé and Natalia Juan Serra, Centro Médico Teknon; Marta Piriz Marabajan and Joaquin López-Contreras Gonzalez, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Olga Melé Sorolla and Cristina Ribó Bonet, Hospital Vithas Lleida; Ana Lerida Urteaga and Lidia Martín González, Hospital de Viladecans; Encarna Maraver Bermudez, Dolors Mas Rubio and Rafel Perez Vidal, Althaia, Xarxa Assistencial Universitària de Manresa. Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Manresa; Susanna Camps Carmona and Conchita Hernández Magide, Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí de Sabadell; Montserrat Gimenez Perez and Nieves Sopena Galindo, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol; M Fernanda Solano Luque, Elena Vidal Diez and M Pilar Barrufet Barque, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme. Hospital de Mataró.