Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a well-recognized adverse drug reaction associated with anti-tuberculosis treatment (ATT), with higher prevalence in people living with HIV (PLWH) concurrently receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART). The incidence of DILI varies widely, ranging from 5% to 33% in patients taking ATT, and from 9% to 30% in those on both ATT and ART, depending on the treatment regimen. This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with the development of DILI in PLWH.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a retrospective case–control study involving 121 patients from August 2015 to December 2023. The study population was PLWH co-infected with tuberculosis (TB) receiving guidelines-based ATT.

ResultsFifty cases with DILI and 71 controls without liver injury were identified. Moderate DILI was observed in 14 patients (27%), and severe DILI in 37 patients (73%). DILI was diagnosed after a median interval of 32.6 days (IQR: 8–47.2), with 56% diagnosed within 30 days and 86% within 60 days of ATT initiation. Baseline BMI, CD4 T cell levels, ALT, and concomitant use of ART were associated with DILI. Furthermore, DILI was associated with increased 3-month all-cause mortality (OR 6.4, 95% CI 1.66–24.7).

ConclusionsA low BMI, high baseline ALT, concomitant ART, and low CD4 T cell levels at the time of TB diagnosis were associated with higher odds of DILI in PLWH. Targeted interventions on these risk factors may help reduce DILI incidence in PLWH and improve clinical outcomes.

La lesión hepática inducida por fármacos (DILI) es una reacción adversa asociada al tratamiento para tuberculosis (TB), particularmente prevalente en personas con VIH que reciben terapia antirretroviral (TAR). La incidencia de DILI varía entre 5-33% en pacientes que reciben tratamiento para TB y 9-30% en aquellos con tratamiento para TB y TAR, dependiendo del esquema. El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar factores de riesgo para DILI en esta población.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles que incluyó 121 adultos con VIH y TB, quienes recibieron tratamiento para TB basado en guías clínicas, entre 2015 y 2023.

ResultadosSe identificaron 50 casos con DILI y 71 controles sin lesión hepática. Se observó DILI moderado en 14 pacientes (27%) y DILI grave en 37 pacientes (73%). Se diagnosticó DILI tras una mediana de 32.6 días (IQR: 8-47.2), 56% durante los primeros 30 días y 86% durante los primeros 60 días desde el inicio del tratamiento. El IMC, los niveles de albúmina y ALT, y el uso concomitante de TAR se asociaron con DILI. La presencia de DILI se asoció con un aumento en la mortalidad general a 3 meses (OR: 6.4, IC95%: 1.66-24.7).

ConclusiónIMC bajo, ALT basal alto, uso de TAR y conteo de células T CD4 al momento del diagnóstico de TB se asociaron con una mayor probabilidad de desarrollar DILI en personas con VIH. Intervenciones dirigidas podrían reducir la incidencia de DILI en esta población y mejorar desenlaces clínicos.

In 2022, an estimated 39 million people worldwide were living with HIV (PLWH), with approximately 1.3 million new infections reported annually.1,2 Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death and hospitalization worldwide among PLWH (accounting for 40% of deaths and 18% of admissions).3 In 2020, TB-related deaths in PLWH were estimated at 214,000, underscoring TB as a significant cause of premature death in this population.4,5

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a well-documented adverse drug reaction associated with anti-tuberculosis treatment (ATT) and is particularly prevalent in PLWH on antiretroviral therapy (ART).6,7 Among hospitalized patients, DILI has emerged as the leading cause of severe liver damage in PLWH, followed by viral hepatitis coinfection.8 The incidence of DILI varies, occurring in 5–33% of patients on ATT and in 9–30% of those receiving both ATT and ART, depending on the treatment regimen.9 An Ethiopian prospective study reported a 10-fold increase in the risk of DILI in patients receiving both ATT and ART compared to those on ATT alone. Furthermore, the incidence of DILI among patients treated with both ATT and ART was significantly higher than among patients receiving either therapy independently, indicating a toxic synergy between these drug groups rather than a mere additive effect.7

Several factors significantly increase the risk of developing DILI among PLWH. These risk factors include elevated baseline ALT and AST levels, a CD4 cell counts below 100cells/mm3, HIV RNA level exceeding 100,000copies/mL, a body mass index (BMI) below 18.5kg/m2, male sex, extrapulmonary TB, low baseline hemoglobin levels, hepatitis B or C virus coinfection, and exposure to other hepatotoxic medications.7,10–12 Due to the ageing HIV population, advanced age has become a relevant risk factor as it has been associated with greater odds of DILI development. In PLWH and TB receiving ART, the risk of DILI increases by 21% for every five-year increment in age.9 In HIV negative, additional risk factors for DILI include alcohol consumption, higher drug doses not corresponding to body weight, underlying liver disease, and slow acetylator status.7,13,14 DILI is associated with poor outcomes; including a mortality rate of 35% within 3 months of diagnosis in cases associated with ATT.15,16 Most population-based studies investigating DILI have focused on Asian or European populations with scarce evidence in the Hispanic population. Only one study performed in the US, found that PLWH of Hispanic ethnicity present a significantly higher risk of severe DILI, compared to Caucasians and African Americans suggesting that ethnicity and genetic background may play a role.17 Moreover, DILI outcomes also differ by regional and racial differences.18 To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined risk factors in the Mexican population. Therefore, objective of this study was to identify clinical risk factors associated with DILI development and DILI-related mortality in Mexican subjects admitted to an HIV Unit at a third-level university hospital.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patient selectionWe conducted a retrospective case–control study involving 121 patients from August 2015 to December 2023 at the HIV Unit of Hospital Civil in Guadalajara, Mexico. Two study groups were defined: 50 cases (patients diagnosed with DILI) and 71 controls (patients without DILI). Eligible patients were PLWH over 18 years of age who were coinfected with TB receiving ATT between 2012 and 2023. Patients were included irrespective of their ART regimen, RNA HIV viral load, or CD4 lymphocyte count status. The development of DILI associated with ATT was assessed during follow-up.

Tuberculosis diagnosis and ATTTB diagnosis was confirmed using the Xpert MTB/RIF (Xpert) assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California) or through culture. HIV infection was validated using screening tests and RNA viral load measurements. All patients received standard treatment for TB consisting of a fixed combination of rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for the initial 2 months (intensive phase), followed by a fixed combination of isoniazid and rifampicin for 4 months (continuation phase), and 10 months for tuberculous meningitis. Doses were tailored according to the patient's pre-treatment body weight. Most of the patients were newly diagnosed with TB. All patients received standard co-trimoxazole prophylaxis as per the current guidelines.19

The standard first-line ART regimen included 300mg tenofovir, 200mg emtricitabine, and 600mg efavirenz prior to 2015. Integrase inhibitor-based regimens were preferentially used once they became available. In patients with integrase inhibitor-based regimens including dolutegravir (DTG) or raltegravir (RAL), dose adjustments were made when starting ATT, consisting of increasing the dosing frequency of DTG 50mg and RAL 400mg from once daily to twice daily. For patients already on ART, treatment was continued, whereas the initiation of ART in treatment-naïve patients was based on their CD4 T cell count at the time of TB diagnosis. ART was initiated within two weeks of starting ATT in patients with a CD4 T cell count ≤50cells/mm3 when TB meningitis was not suspected. For those with a CD4 T cell count above 50cells/mm3, ART was started within 2–8 weeks of ATT initiation, based on current clinical guidelines.19

Data collectionThe data collected included patient demographics (age, sex), HIV-related information (ART regimen, RNA viral load, CD4 lymphocyte count at admission), and details regarding TB diagnosis and treatment (TB location, diagnostic method, ATT with weight-adjusted dosing). Additionally, relevant comorbidities were documented, including hepatitis B and C virus infections, metabolic disease states (obesity, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, and arterial hypertension), and the use of hepatotoxic medications before or during hospitalization. A history of significant alcohol consumption was also recorded (defined as more than three standard drinks per day for males or >30g/day, and more than two standard drinks per day for females or >20g/day).20–22 BMI was calculated based on the measured height and weight at hospital admission. The number and burden of prevalent comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index.23 Current hard drug use was defined as self-reported use and recorded as discrete variable.

The interval between ATT initiation and DILI onset was documented. Liver function test (LFT) values were collected at TB diagnosis and upon the diagnosis of DILI. Other variables such as time to normalization of LFTs, recurrence of DILI, duration of hospitalization, and 3-month mortality rate were also recorded.

Laboratory methods and definition of drug-induced liver injury (DILI)The normal range values for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were 29–33IU/L in males and 19–25IU/L in females. For aspartate aminotransferase (AST), the normal value was 18IU/L for both males and females. Normal range values for gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) (0–50IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (42–98IU/L), total bilirubin (0.2–1.2mg/dL), direct bilirubin (0–0.5mg/dL), and indirect bilirubin (0.1–1mg/dL) levels were determined based on the local laboratory's upper limit of normal (ULN).

The diagnosis of DILI was based on a consensus statement regarding the management of DILI in PLWH treated for TB.24 DILI was defined as an ALT level greater than 120IU/L accompanied by symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, jaundice) or total bilirubin >40μmol/L (2.34mg/dL); or an ALT level exceeding 200IU/L without symptoms, or a total serum bilirubin concentration ≥40μmol/L (2.34mg/dL), regardless of symptoms. According to its severity, DILI was classified as mild when the patient was clinically well with elevated ALT (<200IU/L) and total bilirubin (<40μmol/L) levels. Moderate DILI was defined when the patient was clinically well with elevated ALT (>200IU/L) irrespective of total bilirubin, or with isolated jaundice (ALT <120IU/L and total bilirubin >40μmol/L). Severe DILI was diagnosed when the patient was clinically unwell or symptomatic (nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain) and met the criteria for DILI diagnosis.24 To minimize potential misclassification, we carefully reviewed all cases to rule out immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, and the diagnosis of DILI was retained only when the clinical and temporal relationship with ATT exposure supported this as the primary etiology.

Liver injury was designated as “hepatocellular” when there was a five-fold or higher rise in ALT alone or when the ratio of serum activity (expressed as a multiple of ULN) of ALT to ALP was five or more. Liver injury was termed “cholestatic” when there was a two-fold or higher rise in ALP alone, or when the ratio of serum activity of ALT to ALP was two or less. When the ratio of the serum activity of ALT to ALP was between two and five, liver injury was classified as “mixed”. The pattern of DILI was determined using the first set of laboratory tests available regarding the clinical event.25

Various factors were systematically assessed using the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM), including the timing of drug exposure and liver damage, exclusion of alternative causes, identification of risk factors for adverse hepatic reactions, and monitoring the patient's response to drug re-exposure. Each component of RUCAM is assigned an individual score, and the cumulative scores determine the final assessment for the case. The final score classifies an event as highly probable (>8 points), probable (6–8 points), possible (3–5 points), unlikely (1–2 points), or excluded (0 points).26

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were compared using parametric or non-parametric tests, depending on their distribution. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical program version 1.3.1073 (Vienna, Austria). The association between clinical factors and DILI was first investigated with univariate and then multivariable logistic regression with a backward elimination approach. Variables with a Wald test <0.25 were used in the multivariate model. Goodness-of-fit and model performance were assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (“ResourceSelection” package) and c-statistic (“DescTools” package), respectively. Finally, the association between DILI and 3-month all-cause mortality was estimated with multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, CD4 cell count, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Ethical considerationsThis study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde (approval number: CEI 79/25). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before collecting data from medical records.

ResultsDILI diagnosisData from 121 PLWH receiving ATT were analyzed. Among them, 50 patients (41.3%) were diagnosed with DILI, whereas the remaining 71 patients (58.7%) were considered as controls without liver injury. DILI was diagnosed after a median interval of 32.6 days [IQR 8–47.2], with 56% occurring within 30 days and 86% within 60 days following the initiation of ATT. Most DILI patients exhibited a cholestatic pattern of injury in 23 cases (45%), followed by a mixed pattern in 18 cases (35%), and a hepatocellular pattern in 10 cases (20%). According to the RUCAM score, DILI was possible in 33 patients (66%) and probable in 17 patients (34%). Most patients presented severe DILI (73%, n=37), total oral suspension of ATT was necessary for 23 patients (45%), while partial suspension was required for 16 patients (31%). ATT was reintroduced gradually once LFTs improved, according to current guidelines. Symptomatic disease was observed in 42 patients (82%), of whom 13 (25%) developed hepatic encephalopathy. LFT values normalized after a median of 13 days (IQR 6–29.5).

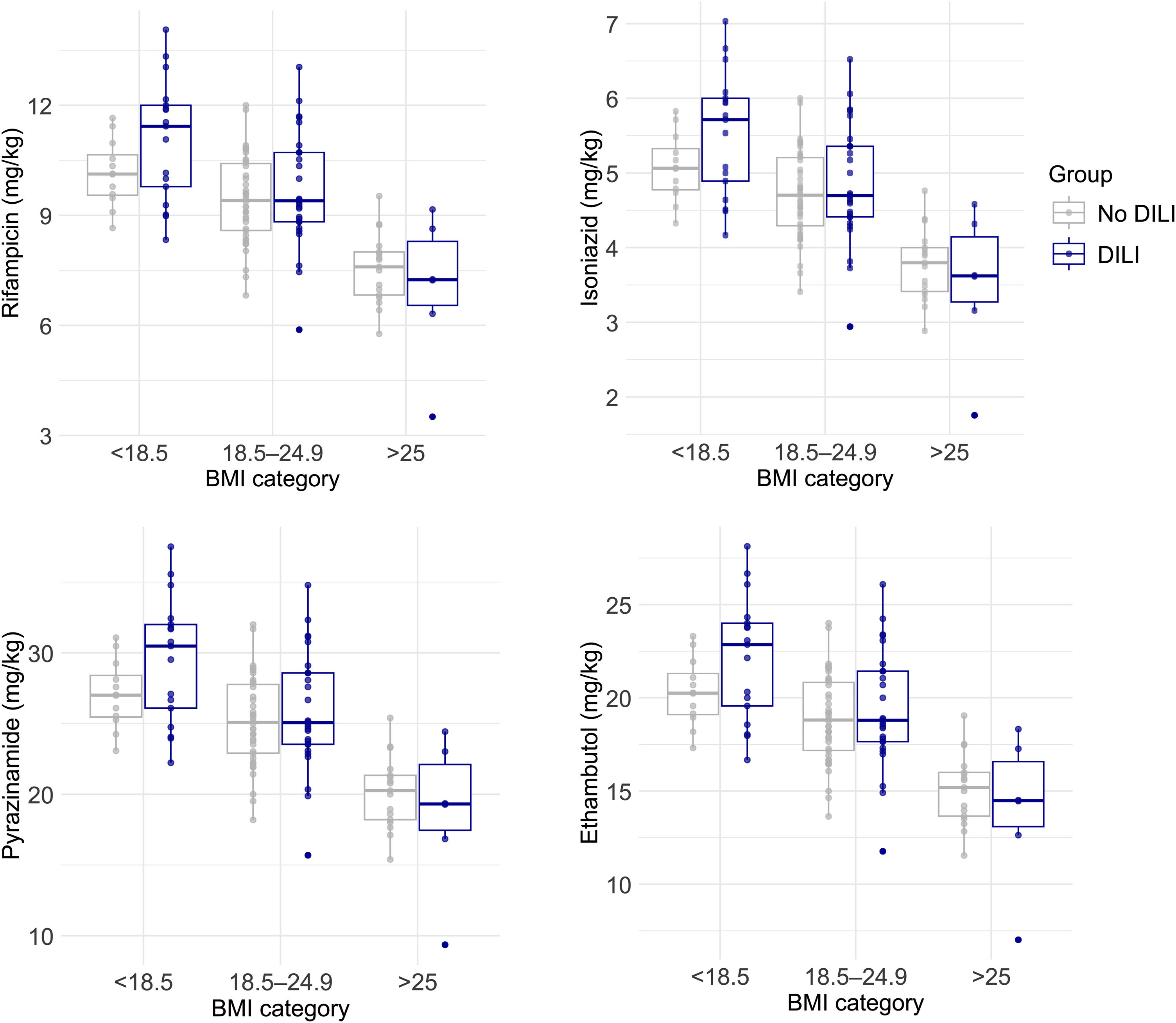

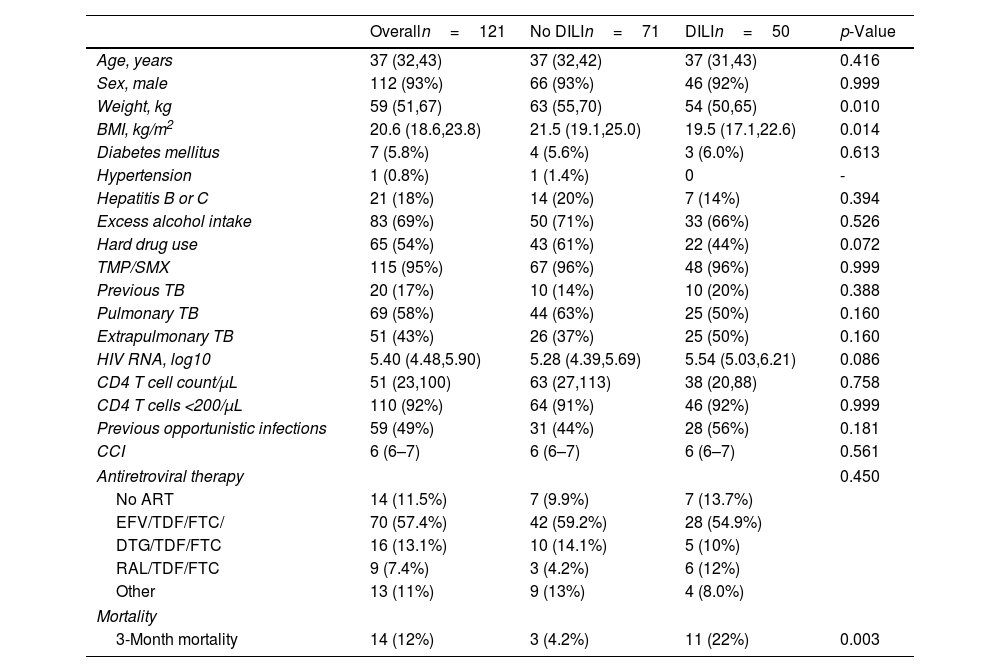

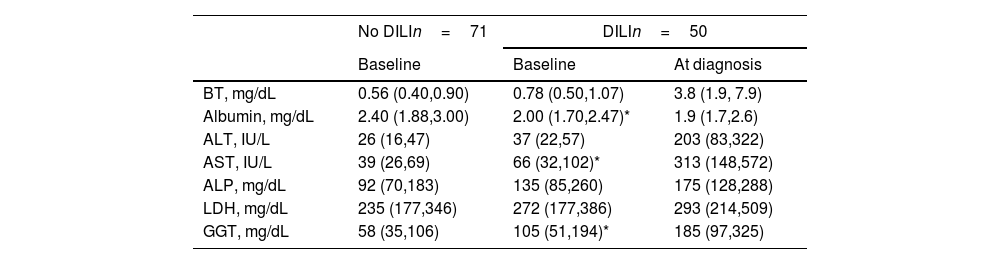

Patient characteristicsThe patient demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. In the overall sample, patients were mostly young males with a high prevalence of low CD4 T cell count <200 (91%). Both groups presented similarly high rates of excess alcohol intake, intake of TMP/SMX, hard drug use and ART regimens. The prevalence of previous TB infection, current TB infection location (pulmonary or extrapulmonary), and comorbid conditions including diabetes mellitus and previous opportunistic infections was similar between DILI and control groups. However, DILI patients had significantly lower body weight (54kg [IQR: 50–65] vs. 63kg [IQR: 55–70]; p=0.010) and BMI compared to controls (19.6 [IQR: 17.3–22.6] vs. 21.5 [IQR: 19.1–24.7]; p=0.021). Weight-based doses of the antituberculosis drugs were higher in patients with low and normal BMI categories compared to those with high BMI. This trend was observed consistently in patients with and without DILI (Fig. 1). Peritoneal TB was more frequent in DILI patients compared to controls (12% vs. 1.4%; p=0.041, Supplementary Table 1). In terms of LFTs, patients with DILI presented significantly lower albumin, higher GGT and AST levels, and a trend toward higher baseline ALT (p=0.061) compared to controls. In contrast, the levels of total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and lactate dehydrogenase were similar between the two groups (Table 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of PLWH and tuberculosis with and without DILI.

| Overalln=121 | No DILIn=71 | DILIn=50 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37 (32,43) | 37 (32,42) | 37 (31,43) | 0.416 |

| Sex, male | 112 (93%) | 66 (93%) | 46 (92%) | 0.999 |

| Weight, kg | 59 (51,67) | 63 (55,70) | 54 (50,65) | 0.010 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.6 (18.6,23.8) | 21.5 (19.1,25.0) | 19.5 (17.1,22.6) | 0.014 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (5.8%) | 4 (5.6%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0.613 |

| Hypertension | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | - |

| Hepatitis B or C | 21 (18%) | 14 (20%) | 7 (14%) | 0.394 |

| Excess alcohol intake | 83 (69%) | 50 (71%) | 33 (66%) | 0.526 |

| Hard drug use | 65 (54%) | 43 (61%) | 22 (44%) | 0.072 |

| TMP/SMX | 115 (95%) | 67 (96%) | 48 (96%) | 0.999 |

| Previous TB | 20 (17%) | 10 (14%) | 10 (20%) | 0.388 |

| Pulmonary TB | 69 (58%) | 44 (63%) | 25 (50%) | 0.160 |

| Extrapulmonary TB | 51 (43%) | 26 (37%) | 25 (50%) | 0.160 |

| HIV RNA, log10 | 5.40 (4.48,5.90) | 5.28 (4.39,5.69) | 5.54 (5.03,6.21) | 0.086 |

| CD4 T cell count/μL | 51 (23,100) | 63 (27,113) | 38 (20,88) | 0.758 |

| CD4 T cells <200/μL | 110 (92%) | 64 (91%) | 46 (92%) | 0.999 |

| Previous opportunistic infections | 59 (49%) | 31 (44%) | 28 (56%) | 0.181 |

| CCI | 6 (6–7) | 6 (6–7) | 6 (6–7) | 0.561 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | 0.450 | |||

| No ART | 14 (11.5%) | 7 (9.9%) | 7 (13.7%) | |

| EFV/TDF/FTC/ | 70 (57.4%) | 42 (59.2%) | 28 (54.9%) | |

| DTG/TDF/FTC | 16 (13.1%) | 10 (14.1%) | 5 (10%) | |

| RAL/TDF/FTC | 9 (7.4%) | 3 (4.2%) | 6 (12%) | |

| Other | 13 (11%) | 9 (13%) | 4 (8.0%) | |

| Mortality | ||||

| 3-Month mortality | 14 (12%) | 3 (4.2%) | 11 (22%) | 0.003 |

Data are presented as the median (IQR) and n (%). BMI, body mass index; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; TB, tuberculosis; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; EFV, efavirenz; TDF, tenofovir; FTC, emtricitabine; DTG, dolutegravir; RAL, raltegravir.

Comparison of baseline liver function tests between groups and at DILI diagnosis.

| No DILIn=71 | DILIn=50 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Baseline | At diagnosis | |

| BT, mg/dL | 0.56 (0.40,0.90) | 0.78 (0.50,1.07) | 3.8 (1.9, 7.9) |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 2.40 (1.88,3.00) | 2.00 (1.70,2.47)* | 1.9 (1.7,2.6) |

| ALT, IU/L | 26 (16,47) | 37 (22,57) | 203 (83,322) |

| AST, IU/L | 39 (26,69) | 66 (32,102)* | 313 (148,572) |

| ALP, mg/dL | 92 (70,183) | 135 (85,260) | 175 (128,288) |

| LDH, mg/dL | 235 (177,346) | 272 (177,386) | 293 (214,509) |

| GGT, mg/dL | 58 (35,106) | 105 (51,194)* | 185 (97,325) |

Data are presented as the median (IQR). BT, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase.

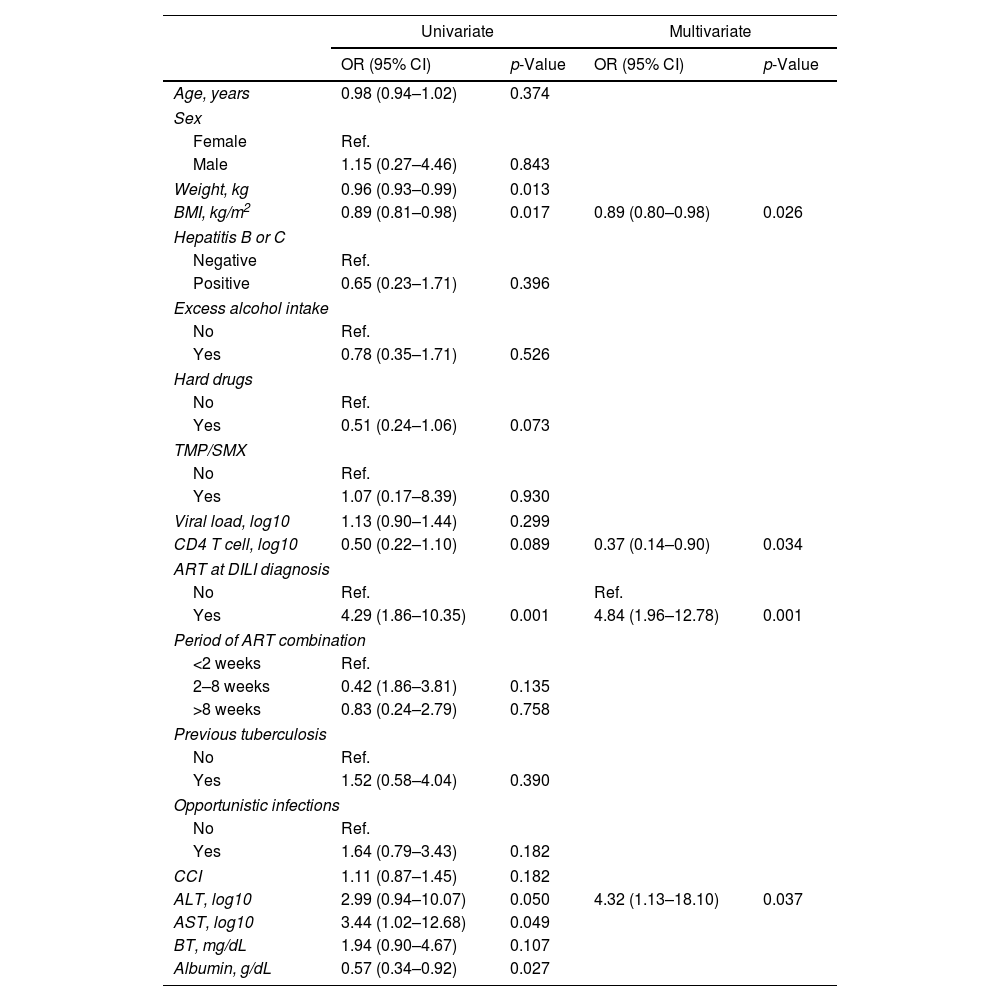

In the univariate analysis, BMI, weight and serum albumin level were inversely associated with DILI, whereas ART at TB diagnosis and ALT level were positively associated with increased risk of DILI. Multivariate analysis showed that lower BMI and CD4 T cell count, baseline ALT and concomitant ART were associated with greater risk of DILI (Table 3).

Association between demographic and clinical characteristics with DILI.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age, years | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.374 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Ref. | |||

| Male | 1.15 (0.27–4.46) | 0.843 | ||

| Weight, kg | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.013 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 0.017 | 0.89 (0.80–0.98) | 0.026 |

| Hepatitis B or C | ||||

| Negative | Ref. | |||

| Positive | 0.65 (0.23–1.71) | 0.396 | ||

| Excess alcohol intake | ||||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 0.78 (0.35–1.71) | 0.526 | ||

| Hard drugs | ||||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 0.51 (0.24–1.06) | 0.073 | ||

| TMP/SMX | ||||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.07 (0.17–8.39) | 0.930 | ||

| Viral load, log10 | 1.13 (0.90–1.44) | 0.299 | ||

| CD4 T cell, log10 | 0.50 (0.22–1.10) | 0.089 | 0.37 (0.14–0.90) | 0.034 |

| ART at DILI diagnosis | ||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 4.29 (1.86–10.35) | 0.001 | 4.84 (1.96–12.78) | 0.001 |

| Period of ART combination | ||||

| <2 weeks | Ref. | |||

| 2–8 weeks | 0.42 (1.86–3.81) | 0.135 | ||

| >8 weeks | 0.83 (0.24–2.79) | 0.758 | ||

| Previous tuberculosis | ||||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.52 (0.58–4.04) | 0.390 | ||

| Opportunistic infections | ||||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.64 (0.79–3.43) | 0.182 | ||

| CCI | 1.11 (0.87–1.45) | 0.182 | ||

| ALT, log10 | 2.99 (0.94–10.07) | 0.050 | 4.32 (1.13–18.10) | 0.037 |

| AST, log10 | 3.44 (1.02–12.68) | 0.049 | ||

| BT, mg/dL | 1.94 (0.90–4.67) | 0.107 | ||

| Albumin, g/dL | 0.57 (0.34–0.92) | 0.027 | ||

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI calculated using binary logistic regression. BMI, body mass index; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; ART, antiretroviral therapy; DILI, drug induced liver injury; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BT, total bilirubin. The period of ART combination reflects the time ranges between antituberculosis treatment and ART. The C-statistic of the multivariate model was 0.767 and the goodness-of-fit was χ2=8.7, p=0.361.

The 3-month mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with DILI compared to controls (n=11 [21.6%] vs. n=3 [4.2%], p=0.004), although only one death in the DILI group was attributed to liver failure. The specific causes of death by group are presented in Supplementary Table 2. DILI were associated with increased risk of 3-month all-cause mortality (aOR 6.19, 95% CI 1.68–31.45), after adjusting for age, sex, T cell CD4 count, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

DiscussionOur study describes a cohort of patients with an unusually high incidence of DILI, likely owing to the presence of multiple risk factors in this population. We found an increased risk of DILI in PLWH treated with ATT with abnormal baseline ALT levels, lower BMI, lower CD4 T cell count, and ART at TB diagnosis. These associations have been previously described in other studies, underscoring the established association between these risk factors and DILI development.10,12,24,27

Abnormal basal liver transaminase levels have been described as an independent risk factor associated with DILI in patients with and without HIV.7,13,14 The proposed causes for these findings include previous viral hepatitis coinfection, mycobacterial liver infiltration, alcohol consumption, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.28 In our study, unadjusted associations were observed for AST and ALT and DILI, but in the multivariate model, only ALT was associated with higher odds of developing DILI. Baseline LFT assessment is not routinely recommended for patients initiating ATT unless they have known risk factors associated with DILI. Although abnormal LFTs are not a contraindication for starting standard ATT, closer monitoring should be performed, especially if additional risk factors are identified.19

A low CD4 T cell count (<100cells/mm3) and a higher baseline RNA HIV viral load, as indexes of HIV disease severity, have been previously identified as risk factors for DILI development.7,10,12,24 An HIV-immunocompromised state could increase the risk of opportunistic infections potentially requiring hepatotoxic drugs for prophylaxis or treatment. For example, one study found that the prescription of fluconazole during the first week of ATT was related to severe liver toxicity, suggesting that the concomitant use of azoles and ATT increases the risk of severe DILI.27 In our study, a lower CD4 T cell count was significantly associated with a higher risk of DILI, with more than 90% of our study population having CD4 T cell counts below 200cells/mm3. This finding is consistent with a retrospective study of hospitalized HIV patients, which reported a univariate association between low CD4 counts and risk of DILI, though this association did not persist in the multivariate analysis.10 Severe immunosuppression may necessitate intensified regimens including hepatotoxic prophylactic medications. However, in our cohort, neither TMP/SMX nor opportunistic infections were associated with DILI. This may suggest that the risk of DILI may derive from other aspects of advanced HIV, including altered drug metabolism or immune dysregulation that require further research. Conversely, it has also been suggested that severely immunosuppressed patients with CD4 T cell counts below 50cells/mm3 may have a lower risk of DILI, possibly due to the absence of immunological mechanisms mediating hypersensitivity-related liver toxicity.27

BMI was significantly lower in patients who presented DILI in this study, with a mean value of 19.6kg/m2 (IQR: 17.3–22.6; p=0.021). We found that a higher BMI was associated with a lower risk for DILI development. A retrospective study conducted in the UK reported similar findings regarding weight-based ATT dose adjustment as a risk factor for DILI.13 Lower BMI has also been identified as a clear risk factor,7 especially in subjects with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2.11 This association may be explained by the impairment of drug metabolism pathways during protein-energy malnutrition, including the acetylation pathways involved in isoniazid metabolism and the depletion of glutathione reserves. This disruption increases susceptibility to oxidative damage and slows the liver's ability to metabolize drugs.29 When analyzing weight-based doses of individual antituberculosis drugs, we found that patients with BMIs in the low and normal ranges consistently received higher doses than those with BMIs in the high range. However, these trends were similar among patients with and without DILI, suggesting that the association between DILI and lower BMI reflects intrinsic risk factors rather than an effect from higher weight-based drug dosing. Importantly, in PLWH and tuberculosis infections may present with significant sarcopenia, which is not necessarily associated with lower BMI. Given this, BMI alone should not be used as a definitive marker of nutritional status, especially in patients with chronic infections.

ATT- or ART-associated DILI has been associated with a high mortality rate. A retrospective observational study from South Africa reported an in-hospital and 3-month mortality among those receiving TB treatment or ART-associated DILI patients of 27% and 35%, respectively. Another retrospective study from the UK, which included only a small proportion of PLWH (7.6%), reported a DILI-attributable mortality of 4.8% in individuals with DILI secondary to ATT.13 In our study, the mortality rate among patients with DILI was 21.6%. Most deaths were related to sepsis, highlighting the high susceptibility to bacterial infections in patients with liver damage.15 Due to a small number of mortality events, all possible predictors of mortality could not be examined in the multivariate model. However, a large cohort reported that higher serum creatinine levels, higher INR, presence of hepatic encephalopathy, and ascites were significantly associated with higher mortality in DILI patients.16

We did not observe an association between age, diabetes mellitus, HIV viral load, opportunistic infections, or comorbidities with the risk of DILI and HIV. While older age (>50 years) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) have been previously associated with DILI,30 diabetes mellitus itself is not associated with DILI. This is noteworthy because diabetes mellitus has been linked to MASLD.31 In our study, only four subjects had diabetes mellitus, and none were diagnosed with hepatic steatosis. Future studies are necessary to clarify whether these conditions are associated with the risk of DILI in this population. Hepatitis B and C infections have been previously described as potential risk factors for hepatotoxicity.14 However, we found no association between viral hepatitis and DILI in our study. One possible explanation is the similar prevalence of chronic hepatitis among DILI patients versus controls (14% vs. 20%, respectively). In addition, the small sample size could have reduced the statistical power needed to detect any contribution of chronic hepatitis to DILI.

Preventing DILI associated with ATT remains a significant challenge in clinical practice. Evidence suggests that preventive interventions, such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC), may be beneficial in managing ATT-related DILI; however, a recent study indicated that NAC did not meet its primary endpoint (time to ALT <100U/L) when compared with placebo. Interestingly, those in the NAC group experienced shorter hospital stays, suggesting some beneficial effects despite not achieving the primary outcome.32 Another study demonstrated that silymarin, a hepatoprotective agent with free radical scavenging properties, reduced the incidence of ATT-DILI by 28% compared with placebo. The proposed mechanism of action for silymarin involves the restoration of superoxide dismutase, which helps mitigate oxidative stress in liver cells.33 Conversely, several other hepatoprotective agents, such as ursodeoxycholic acid, strong neo-minophagen C, and glycyrrhizin, have not shown efficacy in preventing ATT-DILI.34 Due to the high incidence of this complication, particularly among individuals with known risk factors, further clinical trials are necessary to identify effective preventive therapies for ATT-DILI.

Our study identified multiple risk factors associated with the development of DILI in a high-risk Mexican PLWH with TB co-infection, which is consistent with findings from similar populations.7,15 However, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, we were unable to confirm subjects’ adherence to their TB treatment regimen, indicating that some individuals may have missed doses, potentially affecting their overall risk of developing DILI. Second, while we evaluated the presence of relevant basal comorbidities, we did not routinely assess the presence of MASLD, which may also influence risk and serve as a potential confounder. Third, due to the low absolute all-cause mortality rate, we were underpowered to explore the risk factors associated with 3-month mortality in a multivariate model. Fourth, two-thirds of the patients were classified as possible DILI and one-third was categorized as probable on the RUCAM score, representing a limitation, as the probable and highly probable classifications are associated with the highest predictive performance. Lastly, the follow-up period for patients after initiating TB treatment was not standardized, hindering our ability to determine the average timeframe in which DILI developed. Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. It addresses an important clinical problem in a vulnerable high-risk population. In addition, the use of RUCAM as a standardized tool to evaluate the likelihood of DILI reduces the risk of classification bias, improves the reliability and reproducibility of our findings.

ConclusionWe found that PLWH coinfected with TB have an increased risk of DILI, primarily associated with lower BMI, higher basal ALT, and ART at the time of TB diagnosis. Notably, we observed a considerably high mortality of 21.6% among patients who developed DILI. These findings highlight the importance of closely monitoring the LFT's to detect this complication promptly. Preventive interventions for subjects with risk factors for DILI are urgently needed in this population.

CRediT authorship contribution statementPM-A: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. MS-D: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. JV-R: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. LA-G: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. FA-L: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. GA-S: Data curation, Writing, Formal analysis. JA-L: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. CA-R: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. VR-H: Writing and editing. SZ-Q: Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. PS-A: Investigation, Supervision. JA-V: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

FundingThe authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.