People with HIV (PWH) in suppressive antiretroviral treatment suffer from chronic inflammation-related comorbidities, mainly cardiovascular diseases. However, given the lack of specific evidence about inflammation in PWH, clinical guidelines do not provide recommendations for the management of this issue. To date, physician awareness of inflammation in PWH remains unclear. We analyzed the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) related to inflammation, particularly in the clinical management of PWH, of infectious disease specialists (IDS)/internists compared to other specialists treating inflammation directly (rheumatologists) or its cardiovascular consequences (cardiologists).

MethodsA committee of IDS/internists treating PWH, cardiologists, and rheumatologists designed the KAP questionnaire. The survey was completed by 405 participants (135 physicians per specialty) stratified by Spanish geography, hospital size, and number of PWH under care (IDS/internists only).

ResultsIDS/internists treating PWH scored higher than cardiologists and rheumatologists on knowledge of inflammation (5.5±1.4 out of 8 points vs. 5.2±1.3 and 4.6±1.4 points, respectively; p<0.05). Nevertheless, rheumatologists showed the most proactive attitude toward inflammation (i.e., biomarkers monitoring, anti-inflammatory drug prescription and cardiologist referral), followed by cardiologists and IDS/internists (13±3 of a total of 16 points vs. 11±3 and 10±3.3 points, respectively; p<0.05), irrespective of hospital size and years of experience. Most IDS/internists (59%) include inflammation in their therapeutic recommendations. However, in IDS/internists treating PWH, we observed a negative correlation between years of experience and concern about the clinical consequences of inflammation.

ConclusionOur findings show that, compared to other specialists, infectious disease specialists/internists have high knowledge about inflammation in HIV infection, but, in the absence of scientific evidence to base their decisions on inflammatory markers, the therapeutic implications are scarce. The results support the need for more evidence on the monitoring and treatment of inflammation in PWH.

Las personas con VIH (PCV) en tratamiento antirretroviral presentan comorbilidades relacionadas con la inflamación crónica, principalmente enfermedades cardiovasculares. Sin embargo, dada la falta de evidencia específica sobre la inflamación en PCV, las guías clínicas no proporcionan recomendaciones sobre el manejo de este problema. Hasta ahora, no se ha evaluado el conocimiento médico de la inflamación en PCV. Aquí analizamos los conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas (CAP) relacionados con la inflamación, particularmente en el seguimiento clínico de las PCV, de infectólogos/internistas comparados con otros especialistas que tratan la inflamación directamente (reumatólogos) o sus consecuencias cardiovasculares (cardiólogos).

MétodosUn comité formado por las 3especialidades diseñó el cuestionario CAP. La encuesta fue completada por 405 participantes (135 médicos por especialidad) estratificados por geografía española, tamaño del hospital y número de PCV.

ResultadosLos infectólogos/internistas que tratan a PCV puntuaron más alto que los cardiólogos y reumatólogos en conocimiento de la inflamación (5,5±1,4 de 8 puntos frente a 5,2±1,3 y 4,6±1,4 puntos, respectivamente; p<0,05). No obstante, los reumatólogos mostraron una actitud más proactiva hacia la inflamación (es decir, seguimiento de biomarcadores, prescripción de medicamentos antiinflamatorios y derivación al cardiólogo), seguidos de los cardiólogos y los infectólogos/internistas (13±3 de un total de 16 puntos vs. 11±3 y 10±3,3 puntos, respectivamente; p<0,05). La mayoría de los infectólogos/internistas (59%) incluyen la inflamación en sus recomendaciones terapéuticas. Sin embargo, en infectólogos/internistas que tratan PCV, observamos una correlación negativa entre los años de experiencia y la preocupación por las consecuencias clínicas de la inflamación.

ConclusiónNuestros hallazgos muestran que, en comparación con los otros especialistas, los conocimientos sobre inflamación en los infectólogos/internistas son altos, aunque, en ausencia de evidencia científica para condicionar la toma de decisiones a marcadores inflamatorios, las implicaciones terapéuticas escasas. Los resultados apoyan la necesidad de mayor evidencia sobre el seguimiento y el tratamiento de la inflamación en PCV.

Despite the efficacy of antiretroviral treatments (ART) in suppressing the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) load and restoring normal levels of CD4+ cells,1 most people with HIV (PWH) present a spectrum of comorbidities similar to uninfected individuals that are ten years older. These include cardiovascular (CV) diseases, cancer, diabetes, anemia, osteoporosis, and bone fragility.2,3 Several studies have associated PWH premature aging with a characteristic state of low-grade chronic systemic inflammation.3–6 In fact, there appears to be a direct relationship between levels of inflammation markers and morbimortality in PWH.7 In particular, inflammation has been associated with increased occurrence of CV alterations.1,8 Although the management and treatment of CV complications in the context of HIV have been extensively studied,9–15 clinical guidelines have so far made no specific recommendations on monitoring, treatment or prevention of chronic inflammation and CV events in PWH. But the impact of inflammation on health seems to be wider. In PWH, inflammation has been associated to an extensive spectrum of diseases, including emerging conditions such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease16 or obesity.17

In Spain, there is no officially recognized medical specialty of Infectious Diseases. In large hospitals, HIV is managed by medical experts (mainly internists and microbiologists) in infectious diseases, with some of these hospitals having specialized HIV units. In smaller hospitals, however, PWH are managed by internists with varying levels of specialization in treating this condition. We investigated the level of knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) related to inflammation in PWH among this heterogeneous group of physicians. Their answers were compared with those of a group of rheumatologists and cardiologists, specialists who would be expected to have deeper understanding of chronic inflammation and CV disease, respectively. Our findings will allow us to draw a picture of the current state of awareness of professionals treating PWH and will drive further discussion and training on this problem.

MethodsStudy design and questionnaire developmentIn this study, we define an “infectious disease specialist (IDS)” as a physician from any specialty with a monographic dedication to patients with infectious diseases; and we define as “internist” as those from this specialty without monographic dedication to patients with infectious disease. A steering committee consisting of three IDS (SSV, JM, MM) specialized in HIV management, one cardiologist (LPI) and one rheumatologist (CDT) was formed to draft the questionnaire and analyze and interpret the results.

First, we performed a literature review to retrieve recent publications on the state of the knowledge and recommended practices in low grade chronic inflammation in general, and in PWH in particular. Based on these results, we drew up a series of questions to test respondents’ KAP relating to chronic inflammation, including a separate HIV-specific section solely for IDS/internists. Non-HIV-related chronic inflammation questions are defined as those addressed to assess the knowledge/practices of physicians about chronic inflammation in general, while HIV-related chronic inflammation questions were addressed to assess the knowledge/practices of physicians about chronic inflammation in the context of HIV infection.

The final questionnaire consisted of 16 general questions subdivided into three sections: knowledge (n=8), attitude (n=4), and practices (n=4). Four additional HIV-specific questions were generated for each section. The knowledge section consisted of multiple-choice questions. Each correct answer was awarded one point, giving a maximum score of eight points in the general section and four in the IDS/internist section. The attitude and practice sections included a combination of dichotomous, 0–4 Likert scale (no importance at all – highest importance), and multiple response questions. We evaluated each item separately. Even though there are no evidence about monitoring inflammation markers for the follow-up of HIV patients in routine clinical practice, we defined a proactive attitude toward this problem by assessing (1) the importance attributed to (1) chronic inflammation in the prevention of comorbidities; (2) monitoring inflammation biomarkers; (3) having specific drugs available to treat chronic inflammation; and (4) referring patients to a cardiologist.

We conducted a pilot study with a small group of physicians – two IDS, two cardiologists and two rheumatologists – who were asked their opinion on the content, extent and formulation of the questions. Their feedback was implemented in the final version of the questionnaire (see Supplementary Information).

Sample size calculation and inclusion criteriaThe final questionnaire was posted online, and an email with a link to the survey was sent to participants. We calculated that a sample size of 405 participants (135 for each specialty) would be required. To calculate the necessary sample size, we assumed that at least 60% of the participating rheumatologists will have a good or very good knowledge level about chronic inflammation compared to 50% and 40% of IDS/internist and cardiologists, respectively. Following this estimation, we calculated that, to reach a statistical power of 80% with an α=0.05 level, it was necessary to recruit 405 participants (135 for each of the specialties). This sample size estimate was calculated considering a potential loss of 10% of the participants.

The sample was stratified according to Spanish geography, hospital size, and in the case of IDS/internists, proportion of PWH seen in their practice. Selection criteria for participants were: at least 4 years of experience in their specialty; employed in a public hospital; ≥70% of working time devoted to patient care. An additional criterion for IDS/internists was: involved in the care of PWH and responsible for their treatment and follow-up. This last inclusion criterion was implemented to narrow the focus of our study specifically on the subpopulation of IDS/internists with PWH under their care. A geographically representative sample of participants from each specialty was recruited by stratifying centers according to four health areas: north (9,840,865 total population), south (12,426,555 total population), west-center (9,860,217 total population), and east (15,266,587 total population). In the case of cardiology, only clinical specialists and non-interventionists were included. The recruitment, as well as the implementation of the online survey and the fieldwork were carried out by Amber Marketing. Participant recruitment and data collection were blind for both the coordinator, the panel of experts, the company promoting (Gilead Sciences) the study and the scientific consulting company (Medical Science Consulting) that was in charge of analyzing the results.

Data analysis and statisticsWe collected sociodemographic variables (age, sex, region, specialty, years of clinical experience in their specialty, and in the case of IDS/internists, proportion of PWH usually seen), and the answers to the KAP questionnaire.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the sample and categorized continuous variables to facilitate interpretation. Categoric variables were described by frequency and percentage. We used the Chi-square test to compare primary outcomes between specialty groups and analyze differences according to years of experience, hospital size, and proportion of PWH seen. The demographic variables in Table 1 were compared using a Kruskal–Wallis test in the case of continuous variables and a Chi-square test in the case of categoric variables. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.1. Statistical significance level was set at p<0.05.

Participant demographic characteristics and grouping.

| Cardiologist (N=135) | IDS/internist (N=135) | Rheumatologist (N=135) | p-Value | Total (N=405) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | |||||

| Median [Min, Max] | 45.0 [30.0, 66.0] | 51.0 [31.0, 68.0] | 46.0 [30.0, 64.0] | <0.001 | 48.0 [30.0, 68.0] |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (1.5%) | 9 (6.7%) | 40 (29.6%) | 51 (12.6%) | |

| Clinical experience, n (%) | |||||

| <10 years | 38 (28.1%) | 13 (9.6%) | 25 (18.5%) | <0.001 | 76 (18.8%) |

| 10–20 years | 70 (51.9%) | 59 (43.7%) | 61 (45.2%) | 190 (46.9%) | |

| >20 years | 27 (20.0%) | 63 (46.7%) | 49 (36.3%) | 139 (34.3%) | |

| Hospital size, n (%) | |||||

| <500 beds | 43 (31.9%) | 51 (37.8%) | 50 (37.0%) | 0.852 | 144 (35.6%) |

| 500–800 beds | 42 (31.1%) | 44 (32.6%) | 37 (27.4%) | 123 (30.4%) | |

| >800 beds | 50 (37.0%) | 40 (29.6%) | 48 (35.6%) | 138 (34.1%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Man | 89 (65.9%) | 79 (58.5%) | 65 (48.1%) | 0.0319 | 233 (57.5%) |

| Woman | 46 (34.1%) | 56 (41.5%) | 70 (51.9%) | 172 (42.5%) | |

| Type of hospital, n (%) | |||||

| Public and private | 48 (35.6%) | 14 (10.4%) | 35 (25.9%) | <0.001 | 97 (24.0%) |

| Only public | 87 (64.4%) | 121 (89.6%) | 100 (74.1%) | 308 (76.0%) | |

| Proportion of PWH attended | |||||

| Median [Min, Max] | NA [NA, NA] | 50.0 [2.00, 100] | NA [NA, NA] | – | 50.0 [2.00, 100] |

| Missing, n (%) | 135 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 135 (100%) | 270 (66.7%) | |

| Percentage of time in investigation | |||||

| Median [Min, Max] | 5.00 [0,20.0] | 5.00 [0,25.0] | 5.00 [0,25.0] | 0.472 | 5.00 [0,25.0] |

NA: not applicable; PWH: people with HIV.

The study sample consisted of 405 specialists from more than 300 public hospitals of various sizes, representative of the Spanish geography. Participants were subdivided equally into three groups (n=135) (Table 1) with spanned a wide range of age (30–68 years) and clinical experience (4–38 years) in each group. The demographic characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Knowledge about chronic inflammation, related and unrelated to HIVIDS/internists obtained the highest average of correct answers (5.50±1.40 points), followed by cardiologists (5.2±1.3 points) and rheumatologists (4.6±1.4 points). All pairwise differences were statistically significant (Fig. 1A): cardiologists vs. IDS/internists (p=0.043), cardiologists vs. rheumatologists (p=0.0005) and rheumatologists vs. IDS/internists (p=6.4e−07). The analysis of general knowledge according to the size of the hospital (Supplementary Fig. S1A) showed that the differences observed between specialties were accentuated in large and small centers. However, in mid-sized centers, we observed no differences in knowledge among the three specialties. When analyzing knowledge scores according to years of experience in the specialty, more experienced physicians (10–20 years) obtained significantly lower mean scores than less experienced ones (<10 years; p=0.02). Responses were more similar in the subset of specialists with less than 10 years of clinical experience, while variability was greater in the groups with 10–20 years and over 20 years of experience (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

Knowledge of chronic HIV-related and non-HIV-related inflammation. (A) Total knowledge scores. (B) Score from non-HIV-related chronic inflammation questions. (C) Specific knowledge of chronic inflammation and cardiovascular problems in HIV. (D) Advanced HIV knowledge among IDS/internists, according to the % of PWH seen in their clinic. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, n.s.: not significant.

To further clarify knowledge differences between specialties, we separated the HIV-related questions (items 1, 2 and 7) from those dealing with inflammation in general (see complete questionnaire in the Supplementary Information). In the latter, IDS/internists significantly outscored cardiologists and rheumatologists (Fig. 1B). In HIV-specific questions, both IDS/internists and cardiologists significantly outscored rheumatologists (p=1.4e−03 and p=9.4e−05, respectively), who obtained a lower median score with higher dispersion (Fig. 1C).

The second part of the knowledge questionnaire included four additional HIV-specific questions intended for IDS/internists only. We analyzed the results from this section according to the percentage of PWH that each IDS/internist sees in their clinical practice. Interestingly, physicians with a higher proportion of PWH (>50% of patients with HIV) obtained similar mean scores but higher dispersion compared to the other groups (Fig. 1D).

Attitude on chronic inflammation and HIV-related and non-HIV-related cardiovascular riskThis part consisted of four 0–4 Likert scale questions, with a maximum total score of 16 points. In contrast to the knowledge section, rheumatologists showed the most proactive attitude (see definition of proactive attitude in Methods section) toward chronic inflammation problems (13.1±2.2 points), followed by cardiologists (11.1±2.7 points), and lastly, IDS/internists (10.0±3.4 points). All these differences were statistically significant (p<3.0e−10, Fig. 2A). A subanalysis by hospital size showed the same attitude trend in all categories (Supplementary Fig. S2A), although the differences between the three specialties in small hospitals were somewhat smaller. Similarly, the specialist's years of experience do not appear to have a significant influence on their medical attitude (Supplementary Fig. S2B).

Attitude to HIV-related and non-HIV-related chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk. (A) Total attitude score using the Likert scale. **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001. (B) Suitability of using biomarkers to monitor chronic inflammation. (C) Need for specific drugs to treat chronic inflammation. (D) Degree of recommendation to refer PWH to a cardiologist, regardless of their disease status.

Next, we investigated this attitude item by item, since each represents a different aspect of chronic inflammation management. In all cases, the 0–4 Likert scale was used.

Item 1: What importance do you give to chronic inflammation in the prevention of comorbidities in your specialty?Rheumatologists attributed a median of four (highest importance) to the importance of treating chronic inflammation to prevent patient comorbidities (Supplementary Fig. S3), while IDS/internists and cardiologists scored a median of three (high importance).

Item 2: Do you consider it appropriate to monitor biomarkers associated with inflammation (e.g., CRP) in these patients?Rheumatologists gave the highest importance to the use of biomarkers to monitor chronic inflammation in their patients (Fig. 2B), followed by cardiologists and IDS/internists.

Item 3: Do you believe that specific drugs are needed to treat chronic inflammation?The responses to this item indicate that IDS/internists give less importance to having specific drugs available to treat chronic inflammation compared to cardiologists and rheumatologists, with the latter attaching particularly high importance to this item (Fig. 2C).

Item 4: Would you recommend referring HIV patients to a cardiologist regardless of their disease status?IDS/internists give less importance to referring PWH to a cardiologist compared to cardiologists and rheumatologists, who are more likely to give higher importance to this recommendation (Fig. 2D).

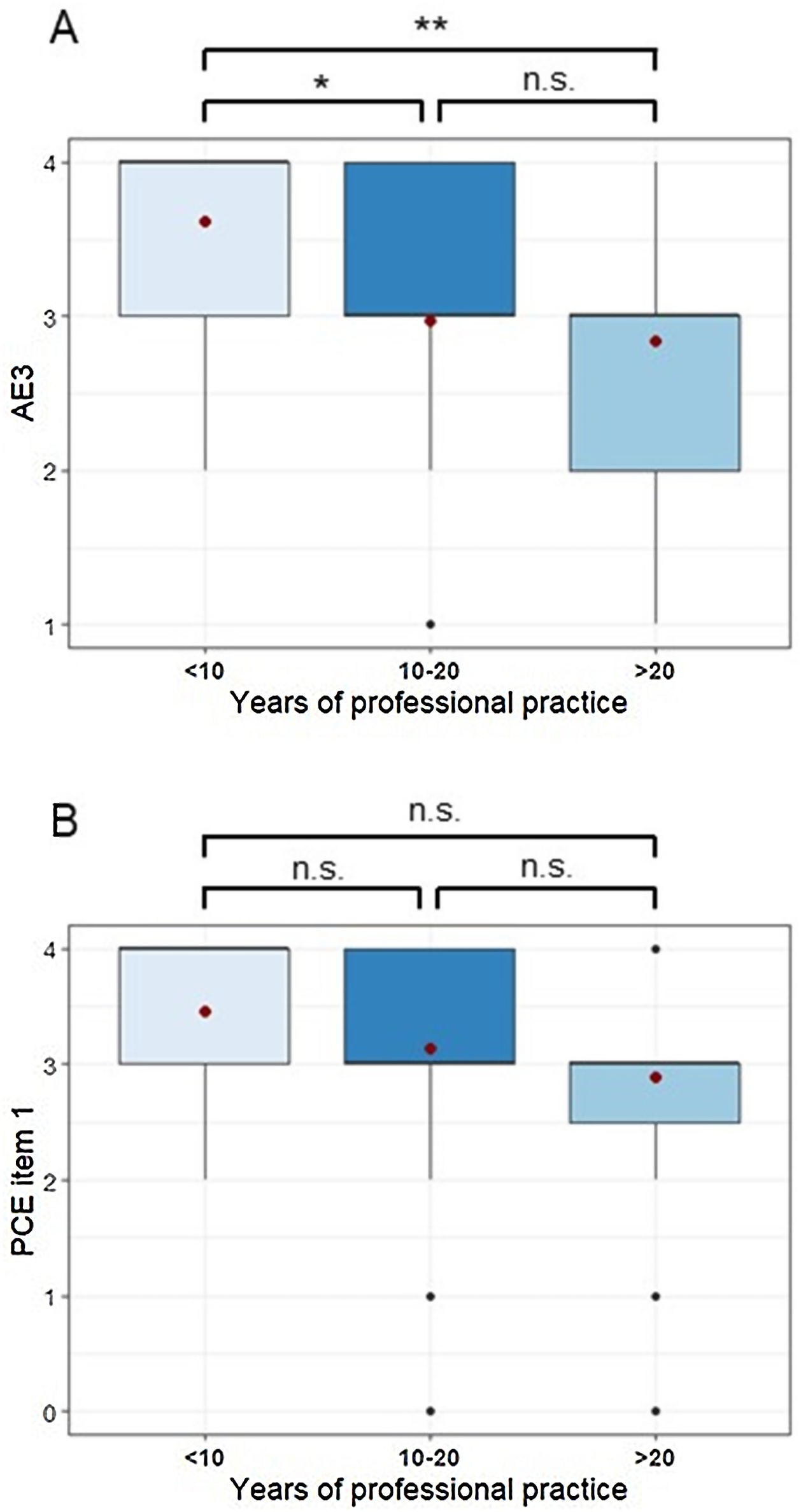

Attitude questionnaire for IDS/internists onlyThe second part of the attitude questionnaire included questions intended solely for IDS/internists. The degree of concern that PWH (on effective ART) may suffer a severe CV event (item AE3 of the questionnaire, see Supplementary Information) negatively correlated with the specialist's years of clinical experience (Fig. 3A). IDS/internists with less than 10 years of clinical experience showed the highest degree of concern about the ART used to treat a patient with a previous CV event with respect to the average of the whole group (item AE4, 3.7±0.5 vs 3.2±0.9). Regardless of their degree of experience with PWH, IDS/internist showed intermediate concern about the phenomenon of microbial translocation in HIV prognosis (item AE1, 2.3±0.9). In addition, most agree that interleukin-6 (IL-6) and D-dimer inflammatory biomarkers should not be systematically monitored, because they fluctuate too much in the same subject and they have no validated cut-off reference points (item AE2, 47.4%).

Attitudes and practices of IDS/internists regarding cardiovascular events in HIV, according to their years of clinical experience. (A) Degree of concern among IDS/internists that HIV patients (on effective ART) could suffer a severe cardiovascular event. (B) Degree of recommendation to change the ART scheme in patients who have suffered a cardiovascular event. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, n.s.: not significant.

A series of questions was designed to identify the practices used by the different specialists when treating chronic inflammation.

Item 1: Do you generally take chronic inflammation into account in the management of HIV patients within your specialty?The question was answered on a Likert scale (0: never – 4: always), and an overall mean of 2.6 was obtained, with no significant differences between specialties.

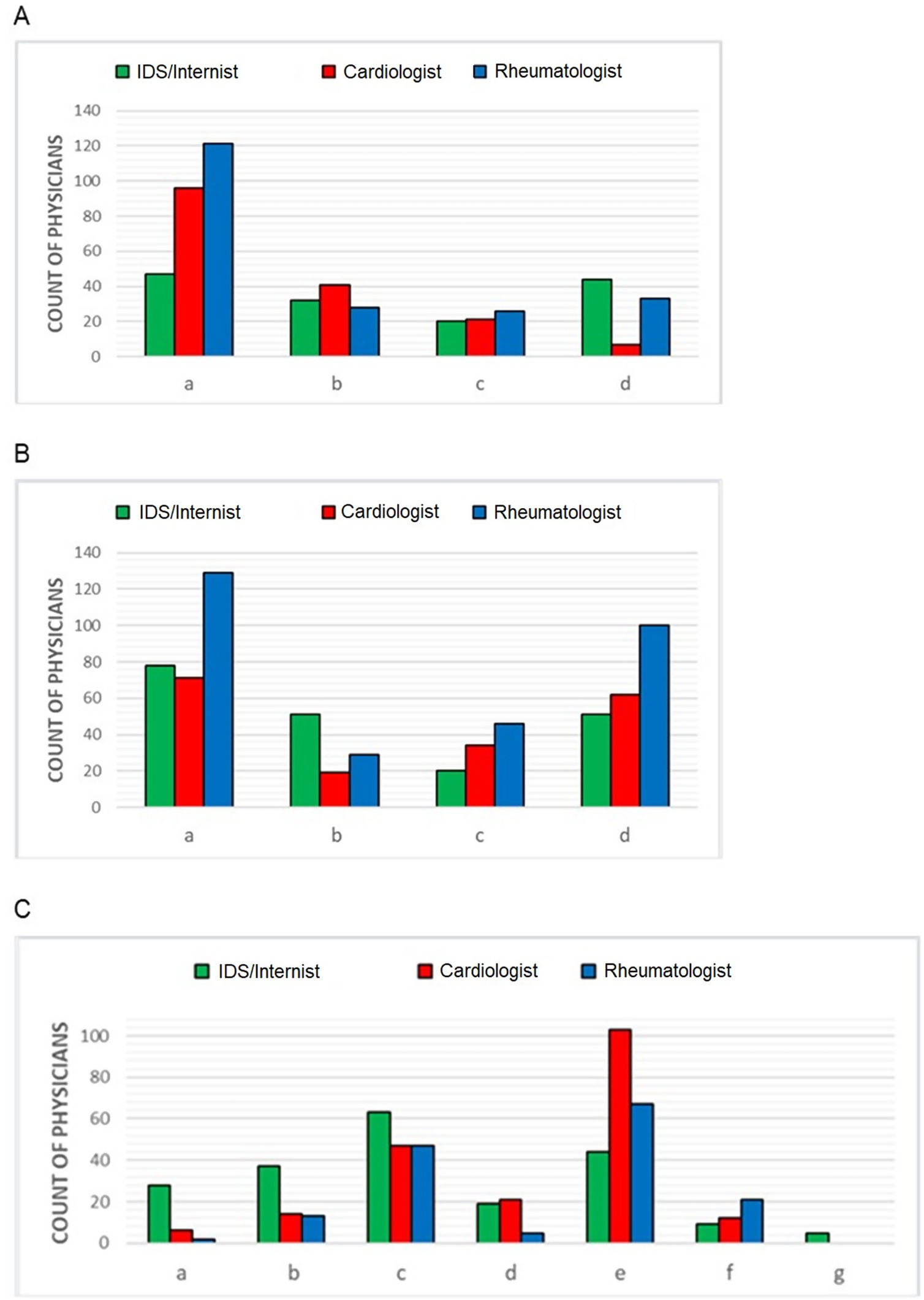

Item 2: Do you evaluate biomarkers associated with chronic systemic inflammation?This was a yes/no question. Respondents answering affirmatively were asked to choose from a list of biomarkers (Supplementary Table 1). More than 90% of rheumatologists recommended the use of biomarkers of chronic inflammation, followed by 71.1% of cardiologists and 42.2% of IDS/internists. Among the specialists who monitor inflammation, the most widely used marker (alone or in combination with others) was C-reactive protein (CRP) (Fig. 4A).

Biomarkers/therapies most commonly used in the context of chronic inflammation and recommended scales to evaluate cardiovascular risk, according to specialty. (A) Most widely used biomarkers to monitor chronic inflammation. (a) C-reactive protein; (b) D-dimer; (c) Interleukin-6; (d) CD4/CD8 fraction. (B) Most widely recommended therapeutic interventions to reduce chronic inflammation. (a) promote a healthy lifestyle in the patient; (b) recommend changes in ART treatment; (c) initiate treatment with acetylsalicylic acid; (d) intensify statin therapy. (C) Most widely used scales to define cardiovascular risk. (a) DAD scale; (b) Framingham (FGH) scale; (c) FGH scale adapted to the Spanish population; (d) American Heart Association scale (AHA/ACC ASCVD); (e) SCORE European scale; (f) none; (g) other.

As expected, almost all rheumatologists (97%) prescribe therapy to reduce chronic systemic inflammation (Supplementary Table 2), but only 53.3% of cardiologists and 58.5% of IDS/internists do so. Intensification of statins and promotion of healthier lifestyles were the most frequently chosen options offered (Fig. 4B).

Item 4: What scale do you use to define cardiovascular risk?The most frequently used CV risk scales (alone or in combination with others) are the European SCORE scale and the Framingham scale adapted to the Spanish population (Fig. 4C). However, while most cardiologists recommend the former scale for CV risk, most IDS/internists prefer the latter.

Practices questionnaire for IDS/internists onlyItem PCE1: Would you consider changing the ART regimen of patients who have had a cardiovascular event?We observed a negative trend between the Likert score of this recommendation (0: I wouldn’t recommend it – 4: I would definitely recommend it) and the respondent's years of clinical experience (Fig. 3B).

Item PCE2: An asymptomatic 53-year-old woman, single and not sexually active, diagnosed with HIV infection with viral load of 3.2logcopies/mL and a CD4 count 853mm−3. Unwilling to start ARTMost IDS/internist replied that the patient should start ART to prevent problems related to chronic inflammation (n=77, 57%), 40.7% considered that she should start ART for other issues unrelated to chronic inflammation, while only a small percentage of clinicians replied that ART should preferably be delayed (n=3, 2.2%).

Item PCE3: Does the presence of chronic inflammation in HIV patients affect your clinical decision-making, such as lowering the threshold for starting statins compared to patients without HIV?The majority of IDS/internist (n=106, 78.5%) stated that chronic inflammation does affect their clinical decisions.

Item PCE4: Does chronic inflammation affect the changes you apply in ART?Most IDS/internists (n=91, 67.4%) indicated that chronic inflammation may influence their decisions about a specific drug class or combination that has been associated with a more favorable anti-inflammatory profile.

DiscussionOur study revealed interesting information about the opinion of IDS/internists in Spain on the problem of chronic inflammation in PWH. They showed a higher level of knowledge compared to cardiologists and rheumatologists in questions on HIV-related or non-HIV-related chronic inflammation. In contrast, they seem less proactive about monitoring and treating HIV-related chronic inflammation problems compared with the other specialties. Finally, we observed a negative correlation between the reported concern for CV complications and the number of years of professional practice of the clinician.

The results of the knowledge section of our study suggest that cardiologists and IDS/internists appear to have greater knowledge of HIV-related questions compared to rheumatologists. Interestingly, in the section of the questionnaire not directly related to HIV (mainly dealing with non-autoimmune chronic inflammation in general), IDS/internists outperformed both rheumatologist and cardiologists. The seemingly lower level of knowledge on this topic among rheumatologists may be explained by the fact that, according to their guideline recommendations, they routinary monitor inflammation caused by autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus18–20; however, since these recommendations do not advise monitoring systemic chronic inflammation in non-autoimmune diseases, e.g. gout,21 rheumatologists could be less well informed than other specialties in this domain. Interestingly, a trend toward an inverse relationship between years of experience and knowledge score was observed in all specialties. This trend may be due to the relatively recent interest in problems derived from chronic inflammation in HIV.

The attitude section of the questionnaire showed that rheumatologists take the most proactive attitude toward inflammation problems compared to IDS/internists. We speculate that rheumatologists are better informed about the benefits of directly treating inflammation, since they routinely deal with diseases in which inflammation is a physio-pathogenic factor. In contrast, IDS/internists generally lack specific tools to properly address chronic inflammation problems. In fact, most IDS/internists reported not using biomarkers to monitor chronic inflammation in their clinical practice and gave less importance to the availability of specific drugs to treat this problem. This could be explained by the current lack of evidence about the use of anti-inflammatory drugs in PWH, in contrast with their use in rheumatic disorders. In fact, most rheumatologists and cardiologists recommended using CRP to monitor chronic inflammation, since this is the method established in their clinical practice for this purpose.22 We speculate that, historically, the main therapeutic focus of IDS/internists has been achieving HIV viral suppression in PWH and preventing the development of secondary diseases traditionally associated with HIV,23 rather than inflammation.

CV complications are one of the main comorbidities associated with chronic inflammation in HIV.24–27 Considering that some active principles used in ART have been reported to increase CV risk in PWH,24–27 we were interested in knowing whether clinicians consider it necessary to refer PWH to a cardiologist. According to our survey, IDS/internists are less likely than cardiologists and rheumatologists to recommend referring a PWH to a cardiologist, regardless of their disease status. This could be due to the fact that, in Spain, IDS/Internists often oversee PWH primary prevention for CV problems. All specialties recommended intensifying statin therapy, probably because they reduce the CV risk associated with inflammation in PWH patients and the general population.28,29 Of note, this study was performed before the preliminary results of the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) study were reported.30 According to the press release, daily pitavastatin in PWH without indication for statin reduced the risk of CV disease. These results will likely impact clinical guidelines and results in an increased prescription of statins in PWH by IDS/Internists.

When we specifically asked IDS/internists about their degree of concern about the development of severe CV problems in PWH, we observed that the score obtained was negatively correlated with the years of experience and age of the physician. This may be because the former were trained prior to the appearance of effective ART, when preventing the morbimortality associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was prioritized. In this regard, younger physicians are more prone to change the ART scheme in patients who have suffered a previous CV event, perhaps because they are more concerned about possible interactions between the drugs used for ART and CV treatment than their older peers. Alternatively, young physicians may be prone to change ART aiming to reduce chronic inflammation. Our results suggest a possible unmet need to implement specific training plans depending on the type of center and the experience of the physicians.

Our study has certain limitations. First, it was conducted in Spain and may not necessarily reflect the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians in other countries or regions. The findings may be influenced by the specific healthcare system, cultural factors, and availability of resources in Spain. Second, the absence of evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding inflammation in PWH is also a limitation of the current results. Lastly, there are limitations associated to intrinsic drawbacks of cross-sectional surveys.31 To control potential biases, we: (1) performed a pilot study with a small group of specialists, and their feedback was used to improve the final version of the questionnaire; (2) recruited a large sample (n=405), including two specialties as external reference; (3) recruited a representative sample in terms of Spanish geography, hospital size, and number of PWH under care.

Our study revealed that IDS/internist specialists have a high level of knowledge about inflammation in HIV infection, but they seldom modify their treatment strategies based on this factor due to the lack of clear guidelines. Most of them agree that starting ART early is important to prevent inflammation-related complications and that chronic inflammation can affect their ART selection. These findings highlight the need for more research on how to monitor and manage HIV infection beyond the conventional markers of HIV RNA plasma levels and CD4+ T cell counts.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

FundingThis research was funded by Gilead Sciences.

Conflict of interestOutside the scope of submitted manuscript, S.S.-V. reports personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Cilag, Gilead Sciences, and MSD as well as non-financial support from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences and research grants from MSD and Gilead Sciences.

The authors thank the participants who completed the questionnaire. Amber Marketing implemented the survey. Medical writing support, including the development of a draft outline and subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, assembling tables and figures, statistical analysis, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, and referencing was provided by Alfonso Picó, Anchel González Barriga and Maria Giovanna Ferrario (Medical Science Consulting SL., Spain), and funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, CA, USA).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version available at doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2023.07.005.