Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is of concern. We describe the epidemiology and assess the vaccination schedule adequacy of IPD episodes (2019–2021) in northern Madrid.

MethodsClinical, laboratory and vaccination data were collected from clinical/epidemiological records. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed according to EUCAST and serotyping by Pneumotest-agglutination/Quellung.

ResultsIPD was identified in 103 patients (71 [IQR 23.5] year-old; 50.4% males), 85.4% associated with bacteremia and a high mortality rate (19.4%). Serotypes 8 (29.9%), 3 and 22F (8% each) were dominant (45.9%), all antibiotic-susceptible. β-Lactams increased MICs and macrolide resistance were mainly linked to serotypes 19A, 23F, 24F, 6C, and 15A. Only 10.5% of adults eligible for vaccination had an adequate vaccine regimen before IPD being 40% due to nonvaccine-preventable serotypes (13, 23B, 24F, 31).

ConclusionIPD episodes were dominated by antibiotic-susceptible ST8 and frequently occurred in adults at risk. Despite recommendations, vaccination adherence rates were very low.

Describimos la epidemiología y evaluamos la adecuación de la vacunación de los episodios de la enfermedad neumocócica invasiva (ENI) (2019-2021) en el norte de Madrid.

MétodosLos datos se obtuvieron de registros clínicos/epidemiológicos, las pruebas de sensibilidad se realizaron mediante criterios EUCAST y el serotipado mediante Pneumotest/Quellung.

ResultadosSe detectaron 103 casos en varones (50,4%) asociados a bacteriemia (85,4%) con una elevada tasa de mortalidad (19,4%). Predominaron (45,9%) los serotipos sensibles a antibióticos: 8, 3 y 22F. El aumento de CMI para β-lactámicos/resistencia a macrólidos se detectó en los serotipos 19A, 23F, 24F, 6C y 15A. Solo el 10,5% de los adultos candidatos a vacunación tenían una adecuada pauta vacunal antes del episodio y el 40% se debió a serotipos no prevenibles mediante vacunación.

ConclusionesLos episodios de ENI ocurrieron frecuentemente en adultos de riesgo y se debieron al serotipo 8. Pese a las recomendaciones, las tasas de adherencia a la vacunación fueron muy bajas.

Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizes the nasopharynx of healthy individuals1 and eventually, it may spread through the bloodstream triggering invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), defined as the isolation of pneumococcus in typically sterile locations. IPD is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide,2 especially children and older populations with risk factors (RF). To prevent pneumococcal disease four vaccines have been sequentially available: three conjugated (PCV7, PCV10 Synflorix®, GlaxoSmithKline and PCV13 Prevnar 13®, Pfizer) and a polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Pneumovax 23®, MSD). Recently, two new conjugate vaccines (PCV15, Vaxneuvance®, MSD and PCV20, Apexxnar®, Pfizer) have been marketed for use in adults (PCV15 also approved for children).3 The conjugate vaccines induce immunological memory and are less prone to lose effectiveness over the years. Traditionally, the recommendations for S. pneumoniae vaccination have considered comorbidities and immune status but varied across regions in Spain.3 The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiology of IPD in a tertiary hospital and to assess the adequacy of the vaccination schedule and its impact on pneumococcal serotype circulation.

MethodsClinical and microbiological dataThis is an observational retrospective study aiming at analyzing IPD detected at Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal tertiary hospital in Madrid from January 2019 to December 2021 (Ethics Committee approval number 215/23). Demographic, clinical and vaccination data were extracted from clinical, microbiological, and epidemiological records. Pneumococcal isolates were serotyped in the Madrid Regional Public Health Laboratory with Pneumotest-Latex agglutination kit and Quellung reaction (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST; penicillin, amoxicillin, cefotaxime, erythromycin, vancomycin, and levofloxacin) was performed (E-test; bioMèrieux, France) and interpreted using EUCAST breakpoints (https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints). Data were analyzed employing STATA™ software v 13.0 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA).

Pneumococcal vaccinationVaccine type and administration dates were extracted from an epidemiological community database and adequacy of vaccine administration before and after IPD was examined according to Region of Madrid recommendations in 2020. For this analysis, only adult patients were included. Patients were considered adequately vaccinated if they received the recommended type and number of vaccine doses appropriate for their age and RF. Three groups were distinguished: adults over 60 years without RF, adults over 15 years old with a chronic pathology, and people of any age with high-RF.4 Patients who received at least one dose of the recommended vaccine before developing IPD episode were considered adequately vaccinated.

ResultsPatient characteristicsDuring the study period, 103 patients with IPD were identified (median age 71 [IQR 23.5] years; 52 [50.4%] male) and only four cases occurred in children (aged 3–13 years). IPD was more frequently identified before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: 59.2% in 2019 vs 24.1% in 2020 and 17.5% (18/103) in 2021. Pneumonia, with (52/103) or without (11/103) concomitant bacteremia, was the most frequent clinical presentation (63; 61.2%). Seventeen (16.5%) patients needed admission to the Intensive Care Unit and 19.4% of the patients (29% in high-risk patients) died within one month after diagnosis (50% having sepsis criteria). Most of the patients (95.2%; 98/103) had some RF for developing IPD, mainly chronic cardiovascular disease (37%; 38/103) and chronic smoking (29%; 30/103) (Table 1). In IPD with a respiratory focus, ceftriaxone (23/74; 31.1%) and piperacillin–tazobactam (20/74; 27.0%) were most frequently prescribed empirical regimens, alone or in combination with levofloxacin or macrolides. Nearly 45% of these treatments were adjusted to ceftriaxone (33/74) in monotherapy. No significant differences regarding admission days were observed in patients with de-escalation in empirical regimen (p>0.05).

Characteristics of patients and S. pneumoniae isolates.

| Feature | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 71 (59–84) | |||

| Man, n (%) | 52 (50.4) | |||

| Clinical | ||||

| Comorbidities, n (%)a | 98 (95.2) | |||

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 38 (37) | |||

| Chronic smoking | 30 (29) | |||

| Diabetes | 25 (24.3) | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 23 (22.3) | |||

| Neurologic/neuromuscular disease | 8 (7.8) | |||

| High-risk factors, n (%)a | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (7.8) | |||

| Liver cirrhosis | 6 (5.8) | |||

| IPD history | 6 (5.8) | |||

| HPSTC | 4 (3.9) | |||

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory disease | 73 (70.9) | |||

| Meningitis | 13 (12.6) | |||

| Isolated bacteremia | 3 (2.9) | |||

| Septic arthritis | 3 (2.9) | |||

| Others | 11 (10.6) | |||

| Median admission days, n (IQR) | 8 (4–20) | |||

| 30-Day mortality, n (%) | 20 (19.4) | |||

| Microbiological features | ||||

| No of serotype detected, serotype | ||||

| n=26 | 8 | |||

| n=7 | 3, 22F | |||

| n=4 | 19A | |||

| n=3 each | 4, 15A, 23B, 23F, 35B | |||

| n=2 each | 10A, 12B, 15B, 24F, 35F, 6C, 9N | |||

| Serotype distribution per year, n (%)b | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total |

| Covered by PCV13 | 15 (24.6) | 5 (20.8) | 2 (11.1) | 22 (21.4) |

| Additionally covered by PPS23V | 22 (36.1) | 9 (37.5) | 10 (55.6) | 41 (39.8) |

| Non covered by PCV13–PPS23V | 14 (23.0) | 6 (25.0) | 3 (16.7) | 23 (22.3) |

| Serotype not available | 10 (16.4) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (16.7) | 17 (16.5) |

| Total, n | 61 | 24 | 18 | 103 |

| Antimicrobial susceptibility (n=88) | %S | %I | %R | MIC50–MIC90c |

| Penicillin | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0.023–1 |

| Amoxicillin | 87.5 | 4.6 | 7.9 | 0.023–1.5 |

| Cefotaxime | 94.4 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 0.016–0.5 |

| Erythromycin | 80.7 | – | 19.3 | 0.13–>256 |

| Vancomycin | 100 | – | 0 | 0.5–0.75 |

| Levofloxacin | – | 100 | 0 | 1–1.5 |

IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; HPSTC, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell transplantat; IQR, interquartile range; PCV13, pneumococcal conjugate 13-valent vaccine; PPS23V, pneumococcal polysaccharide 23-valent vaccine; S, susceptible; I, susceptible increased exposure; R, resistant.

S. pneumoniae was isolated in blood cultures of 88 patients (85.4%), and in 11 of them, also from other sterile fluids (8 CSF, 2 pleural and 1 synovial fluids). In 15 patients S. pneumoniae was recovered only from pleural fluid (n=7), CSF (n=3), peritoneal (n=2) or synovial fluids (n=2) and vitreous humor (n=1). Twenty-nine different serotypes were identified (84.5%, 87/103 available for serotyping), 11 of which were not included in either PCV13 or PPSV23, representing 21.6% of all IPD episodes. Serotypes 8 (26/87; 29.9%), 3 and 22F (14/87; 8% each) were responsible for 38.8% of IPD cases being serotype 8 the most prevalent throughout the entire study period (Table 1). Meningitis cases (8/13 available) involved various serotypes, including 3, 7F, 8, 19A, 22F, 31, and 33. Influenza virus co-detections occurred in 6.8% of cases: four (3.9%) in 2019, one (0.9%) in 2020, and two (1.9%) in 2021. Additionally, only one (1.1%) case of SARS-CoV-2 co-infection was detected in 2020. Pneumococcal urinary antigen testing was performed in 72.6% of patients with pneumonia (45/62), being positive in only 62.2% of the cases. No association was found between the serotype responsible for the IPD and a negative urinary pneumococcal antigen result.

All isolates were susceptible to penicillin (including 22 [25%] categorized as susceptible with increased exposure; I), vancomycin and levofloxacin (all categorized as I) (Table 1). Isolates with resistance and/or increased MICs to β-lactams (22/88) mainly belonged to serotypes ST19A, 23B, 23F (n=3; 13.6% each) and 6C, 15A, 24F and 35B (n=2; 9.1% each). Macrolide resistance (n=17) was mainly associated with serotypes 19A and 23F (n=3 each; 17.6% each), and 6C, 15A and 24F (n=2; 11.8% each). All isolates belonging to serotype 8 were susceptible to the antibiotics tested.

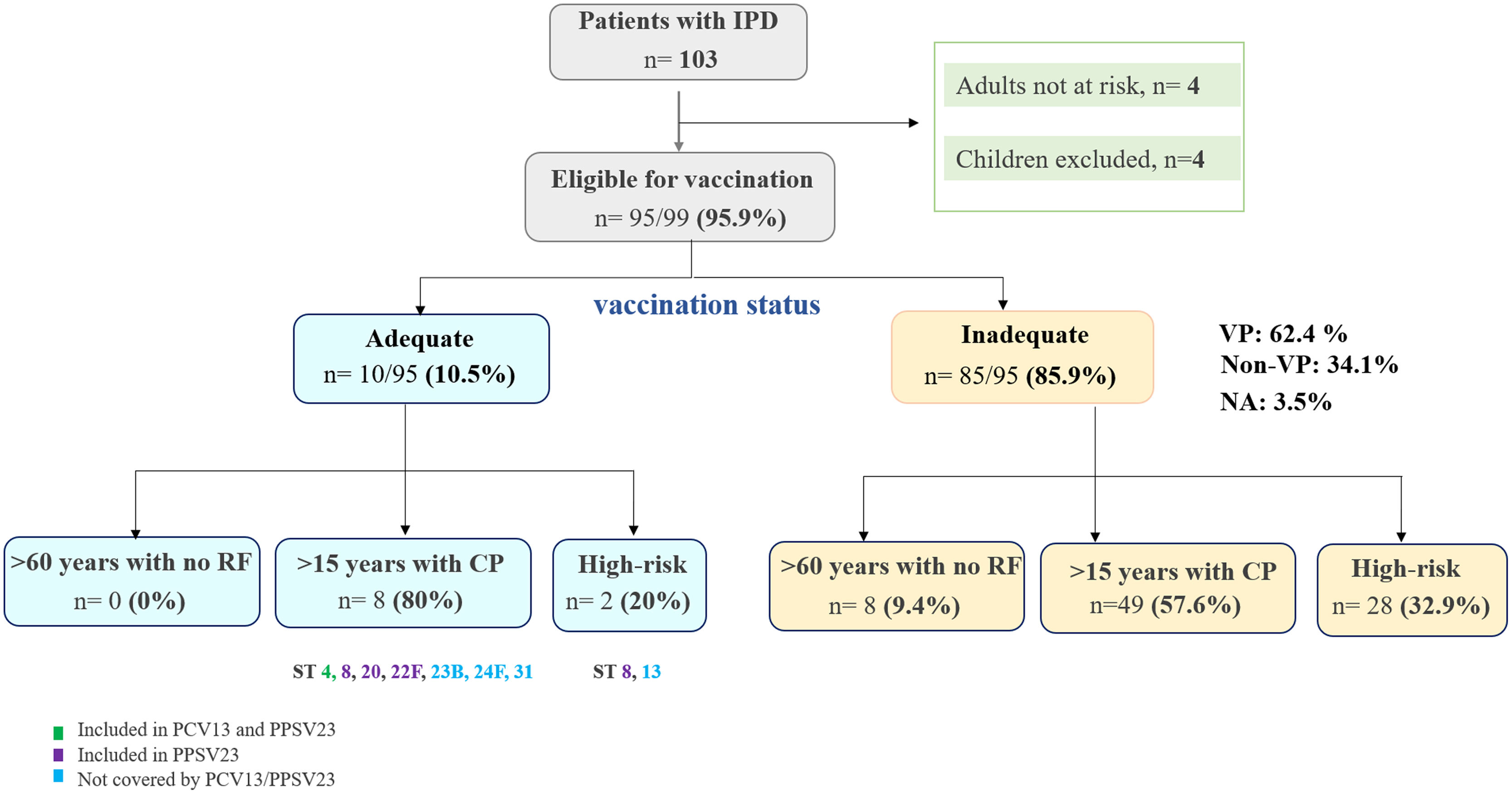

Vaccine administration and adequacyBefore the IPD episode, only 10.5% (10/95) of adult patients eligible for vaccination had an adequate vaccination schedule according to their risk group (Fig. 1). These patients had received at least one dose of PCV13, and 6 of them, additionally, at least one dose of PPSV23 within 5 years. Of the latter, all but one had IPD by a nonvaccine-preventable serotype (13, 23B, 24F, 31). The only vaccine failure detected was due to serotype 8, occurring in a patient with a history of immunosuppression. Therefore, the majority (85.8%; 85/99) of adult patients at risk did not have an adequate vaccine status. At least 53 IPD episodes could have been potentially prevented, as they were caused by serotypes covered by either the PCV13 (18/53) (serotypes 3, n=7; 19A, n=3; 23F, n=3; 4, n=2; 9V, n=1; 14, n=1; 18C, n=1) or PPSV23 (53/53) vaccine (Fig. 1). Remarkably, only 6.6% (2/30) of high-risk patients were adequately vaccinated, with 43.3% (13/30) not receiving any vaccine before IPD episode. After the IPD, only 16% (16/100) of adult patients received an adequate vaccine.

Vaccine administration before IPD episodes. Adequacy of vaccination regimen prior to IPD episode according to risk groups considered by Madrid Community (4). Abbreviations: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; RF, risk factors; CP, chronic pathology; VP, vaccine preventable; NA, not available; ST, serotype; PCV13, pneumococcal conjugate 13-valent vaccine; PPS23V, pneumococcal polysaccharide 23-valent vaccine.

This study highlights the severity of IPD and the importance of vaccination in patients at risk, revealing that one in five patients diagnosed with IPD died within a month with nearly half of them with sepsis. Despite having multiple comorbidities, only one in 10 adult patients was correctly vaccinated at the time IPD diagnosis. Notably, only one case was due to vaccine failure involving serotype 8, which PPV23 could potentially prevent, possibly due to the lower immunogenicity of this vaccine and the patient's history of immunosuppression.5 PCV13 has shown high effectiveness in preventing IPD in both infants (85–98%) and adults, though its effectiveness against serotype 3 is lower (20–80%). Studies suggest waning immunity after booster doses in children, particularly for serotypes 3 and 19A,6,7 which may explain the continued prevalence of serotype 3 in adult IPD cases. During the first two years of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, a reduction in nosocomial IPD incidence was observed,8,9 likely due to containment measures that involved reduced respiratory transmission, surveillance failures and changes in primary care-seeking behavior.10 Only three serotypes (3, 8, and 22F) caused nearly half of all IPD cases, with serotype 8 being the most prevalent.11 Serotype 8, once linked to HIV,12 is now common in adults over 60 with cardiovascular pathologies. Its rise in Madrid has been attributed to the replacement of clone 8-ST63 with the less resistant 8-ST53.13 In Europe, the approval of new conjugate pneumococcal vaccines for adults (PCV15 and PCV20) and the development of future vaccines (PCV21, PCV24, PCV26) necessitates the review of current recommendations for vaccination considering the serotype replacement that may subsequently occur. There is a trend toward replacing polysaccharide with conjugated vaccines, which could prevent current issues associated with sequential schedules. Given the challenge of influencing government vaccination policies, the focus should be on raising awareness of low adult vaccination rates compared to children. It is essential training primary care professionals to emphasize the need and benefits of vaccination for the target population over 65 to promote healthier aging and to reduce incidence and mortality of a disease that is always on the agenda.

FundingThis study was partially supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Infecciosas (CIBERINFEC) (CB21/13/00084).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We thank laboratory technicians of blood culture section in the Microbiology Department.

The results of this study were partially presented at the 32nd European Congress of Clinical Microbioloy and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID).