Healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) in neonates are frequent and highly lethal, in particular those caused by extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing bacteria. We evaluated the beneficial effects of ultraviolet C (UV-C) disinfection and copper adhesive plating on HCAIs in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) of a third level paediatric hospital in Mexico City, both in combination of hand-hygiene (HH) and prevention bundles.

MethodsAll NICU patients were included. There were 4 periods (P): P1: HH monitoring and prevention bundles; P2: P1+UV-C disinfection; P3: P2+Copper adhesive plating on frequent-contact surfaces and P4: Monitoring of P3 actions.

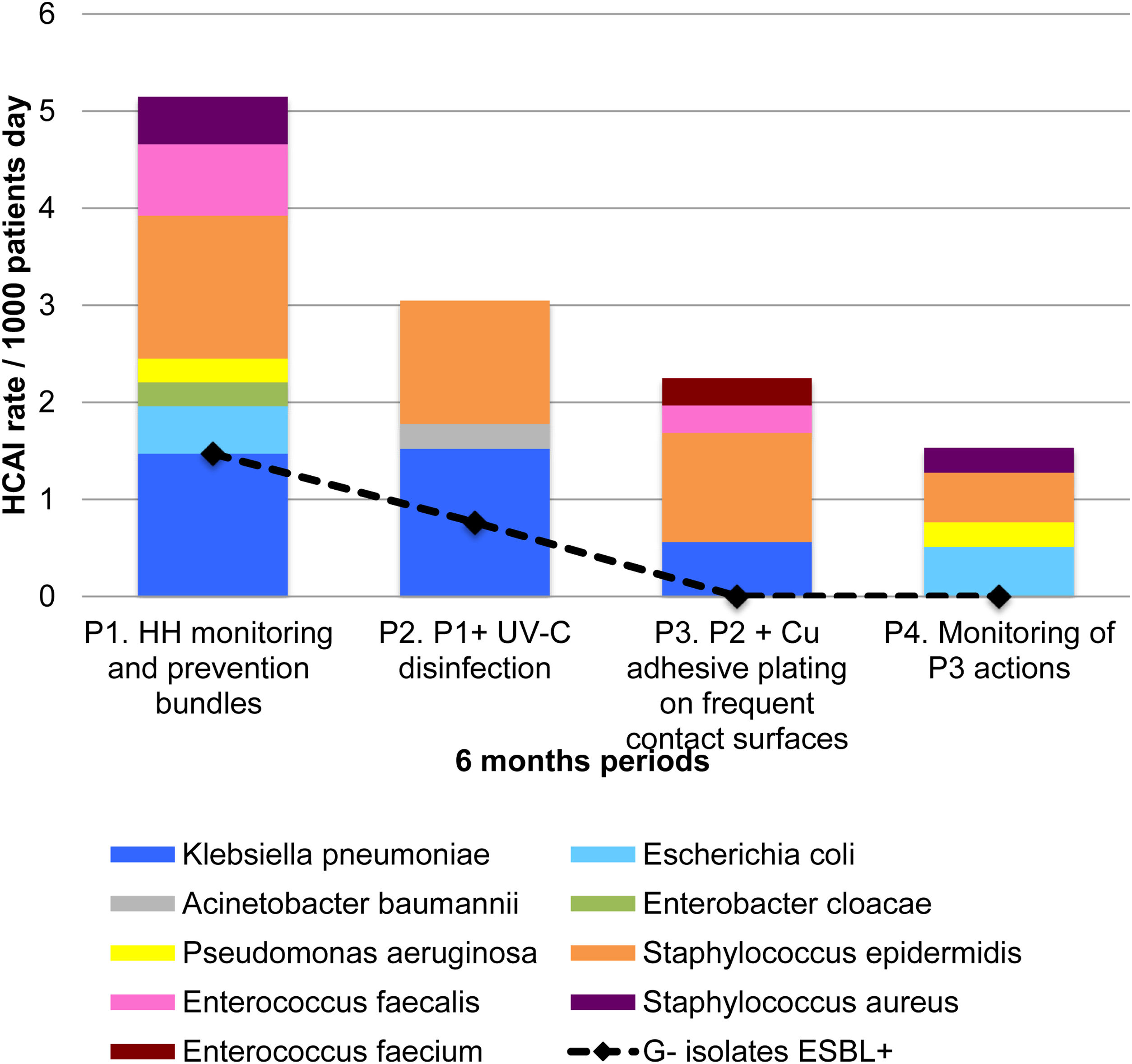

Results552 neonates were monitored during 15,467 patient days (PD). HCAI rates decreased from 11.03/1000 PD in P1 to 5.35/1000 PD in P4 (p=0.006). HCAIs with bacterial isolates dropped from 5.39/1000 PD in PI to 1.79/1000 PD in P4 (p=0.011). UV-C and copper were associated with significant HCAI prevention (RR 0.49, CI95% 0.30–0.81, p=0.005) and with lesser HCAIs with bacterial isolates (RR 0.33, CI95% 0.14–0.77, p=0.011).

ConclusionsCopper adhesive plating combined with UV-C disinfection were associated with a drop in HCAI rates and with the elimination of ESBL-caused HCAIs. Hence, we propose that these strategies be considered in MDRO proliferation preventions.

Las infecciones asociadas a la atención a la salud (IAAS) en neonatos son frecuentes y altamente letales, en particular las causadas por bacterias productoras de BLEE. Se evaluaron los efectos de la desinfección por UV-C y las placas adhesivas de cobre sobre las IAAS en la unidad de cuidados intensivos neonatales (UCIN) de un hospital pediátrico de tercer nivel en la Ciudad de México, en combinación con higiene de manos (HM) y con paquetes de prevención.

MétodosSe incluyeron todos los pacientes de la UCIN. Hubo 4 periodos (P): P1: monitorización de HM y paquetes preventivos; P2: P1 + desinfección con UV-C; P3: P2 + recubrimiento con placas de cobre en superficies de alto contacto y P4: monitorización de acciones de P3.

ResultadosQuinientos cincuenta y dos neonatos fueron monitoreados durante 15,467 días/paciente (DP). Las tasas de IAAS disminuyeron de 11,03/1.000 DP en P1 a 5,35/1.000 DP en P4 (p=0,006). Las IAAS con aislamiento bacteriano disminuyeron de 5,39/1.000 DP en P1 a 1,79/1.000 DP en P4 (p=0,011). La UV-C y el cobre se asociaron con una prevención significativa de las IAAS (RR: 0,49; IC 95%: 0,30-0,81; p=0,005) y con menores IAAS con aislados bacterianos (RR: 0,33; IC 95%: 0,14-0,77; p=0,011).

ConclusionesLas placas adhesivas de cobre combinadas con la desinfección por UV-C se asociaron con una caída en las tasas de IAAS, y con la eliminación de las IAAS causadas por BLEE. Por lo tanto, proponemos que estas estrategias se consideren en la prevención de la proliferación de MDRO.

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) associated infections have become one of the major causes of death worldwide1 and a public health matter of importance.2 Moreover, healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) continue to contribute greatly to the global death rate3 aggravated by the increasing prevalence of MDRO.4

According to the European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), paediatric HCAI prevalence is nearly 4%, but this figure is more than double in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) environments, where more than one in ten newborns (10.7% CI 95% 9–12.7%) acquire a type of HCAIs.5

The prevalence of infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) producing bacteria in newborns has been reported as high as 11% (CI 95% 6–17%) and appears to be increasing by approximately 3.2% annually. It is associated with twice the mortality percentage when compared to HCAIs caused by other organisms (36% and 18%, respectively).6

Furthermore, the important role played by hospital environmental surfaces in the transmission of ESBL-producing bacteria has been reported.7 The use of UV-C light has been shown to reduce the rate of HCAIs caused by these group of microorganisms and is one of the preferred terminal cleaning methods.8 The biocidal effect of copper has also been proven, although there are very few studies, which have assessed the impact of its use on infections caused by MDRO, particularly in the case of newly born patients.9,10 When used for prevention purposes, copper has advantages, in terms of reducing the number of infections, such as aiding in the reduction of antibiotic use and length of hospital stay.11,12

This study was undertaken to assess the staggered effect of UV-C and copper adhesive plating (CAP), within the context of NICU with a high incidence of HCAIs caused by ESBL-producing bacteria. The effect of the strategies on the contamination of high-contact surfaces was also measured.

MethodologyThe study was conducted at the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG), a third level national referral paediatric hospital in Mexico. The NICU of the hospital has 26 beds and receives an annual average of 267 patients with approximately 6460 patient-day (PD) (Mean 7.5 PD, SD 2.7). Intensive care is provided for surgical pathologies, premature patients and other medical conditions. The hospital implemented a hand hygiene (HH) programme in 2013 whose methods and results have already been published.13 Since then, subsequent implementation of prevention bundles has also been documented.14

The project undertaken involved a four-stage quasi-experimental study. Each stage was designed to last six months. The design was as follows: Phase 1 (P1) covered only HH and prevention bundle monitoring; Phase 2 (P2); covered the use of UV-C light exposure in combination with P1; Phase 3 (P3), the placement of copper adhesive plates on high-contact NICU surfaces plus P1 and P2 actions. During Phase 4 (P4) all previous actions continued and were monitored.

All patients admitted to NICU from December 26, 2017 to December 26, 2019 were included in the study. Active HCAI epidemiological surveillance was carried out by hospital epidemiologists and infectious disease physicians with strict adherence to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHS) criteria.15 Surveillance at HIMFG has been previously reported by the authors.13 This consists of daily visits to NICU by trained nurses with the objective of gathering HCAI data. In addition, data were recorded for patient-days, central line-days, catheter-days, ventilator-days, surgical interventions and clinical evolution of surgical wounds. The nursing staff also monitored HH and prevention bundles, mainly central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) prevention bundles.

Vitek R 2 XL equipment and the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration by micro-dilution technique were used for the antimicrobial susceptibility test. Vancomycin-resistance was verified according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. This identification was carried out by means of mass spectrometry in the VITEKR MS equipment. ESBL detection was carried out according to the CLSI recommendations, that is, with a phenotypic confirmatory combined disc test. This test consists of measuring the growth-inhibitory zones around discs of clavulanate and third and fourth generation cephalosporins. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to methicillin was performed using cefoxitin. For the control, reference strains, American type culture collection was used.

HH was monitored using previously described protocols.16 Trained covert observers, validated using WHO criteria,16 were assigned by the epidemiology department. These people visited the NICU once a month to perform surveillance. Also, feedback for NICU staff was provided once a month. Training in a prevention bundle to prevent bacteraemia, based on no-touch aseptic techniques,17 has been in place at the hospital since 201614 and remained unchanged during the study period.

NICU incubator washing and disinfection actions: For washing, all incubator detachable parts were removed and soaked in an enzymatic cleaner for 15min. Thereafter, they were dried with a towel, reassembled disinfected with a 400ppm chlorine solution. Non-detachable incubator parts were first cleaned with an enzymatic cleaner and then disinfected with a 70% alcohol solution. Surface cleaning was done on a daily basis, while washing was done every time a new patient was admitted or on the contrary, every 15 days. When an incubator was soiled, the patient was transferred to a clean incubator. The head nurse in each shift supervised these procedures.

P2 started in June 2018 by disinfecting incubators twice a week by exposure to UV-C (UVDI-360, INIMED S.A. de C.V.). All the detachable parts of the incubator were separated to facilitate their disinfection on all sides. Other medical equipment and cell-phones were placed in an uncontaminated room and each side of these was exposed to UV-C light (UVDI-360®) for five minutes, at a distance of 2.4m and a setting of 254nm, 2–3 times a week.

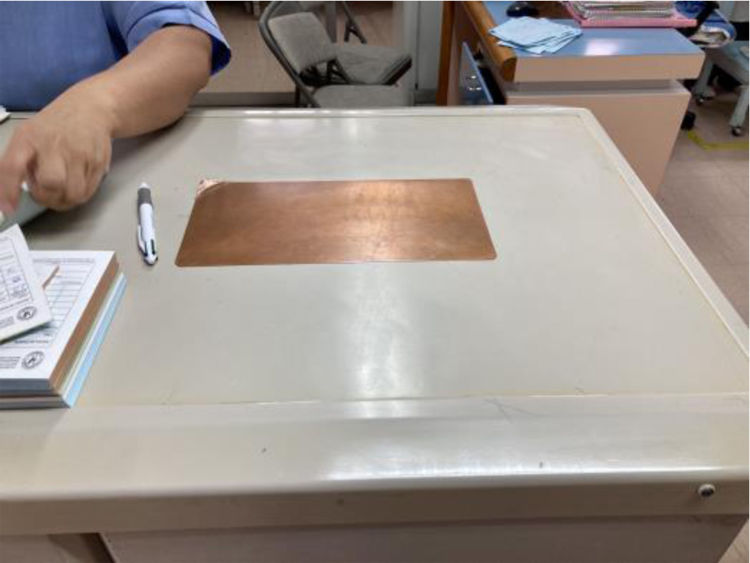

In January 2019, a total of 158 copper adhesive plates were placed on frequent-contact surfaces for P3 as follows: 112 in the incubators, 20 on tables, 17 on chairs, 2 on ultra-sound equipment, 1 on the nurse control station table, 1 on the telephone handset, 2 on weighing scales, 2 on door handles and 1 on the refrigerator handle. There were some complications for the placement of the copper plates. For example, the provider could not put a copper square on each key of the ultrasound keyboard. However, since the handle is always taken to move the ultrasound from one patient to another, it was decided to put the plate there. If any copper adhesive plate came off, the supplier would change it in a maximum period of 3 days.

Statistical analyses were done with STATA 13. Measures of central tendency were calculated. To evaluate statistical differences between groups, Kruskal–Wallis, Chi squared and Chi squared for linear trend tests were applied. Logistic regression was used to calculate HCAIs, death and ESBL risk. To avoid the family-wise error, Bonferroni correction was used.

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics and research committee of HIMFG.

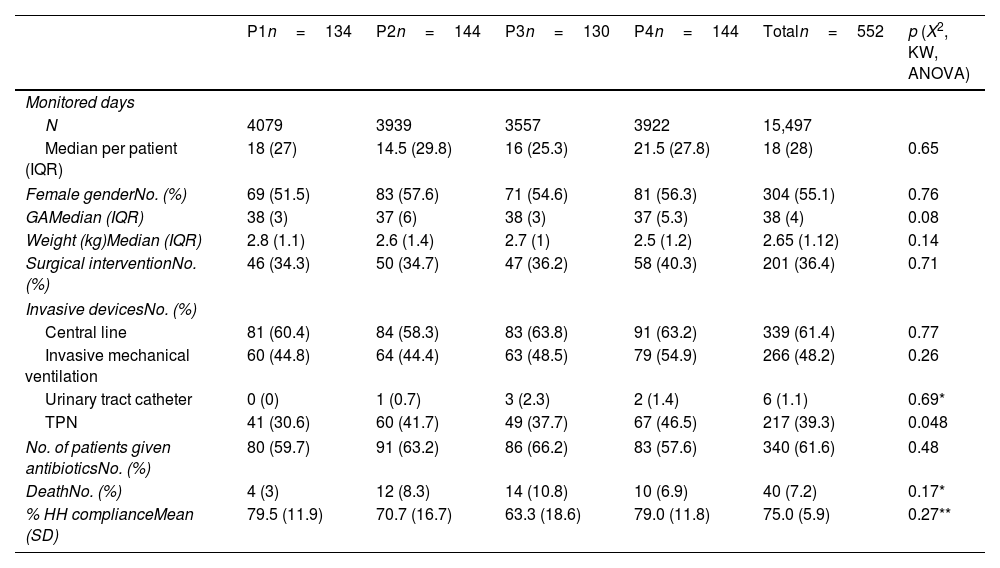

ResultsFrom December 26, 2017 to December 26, 2019, 15,497 PD of 552 infants were recorded. Our analysis did not yield statistical differences for gender, gestational age, length, weight, surgical intervention, use of invasive devices, antibiotic use or deaths between the study periods (Table 1).

Baseline data.

| P1n=134 | P2n=144 | P3n=130 | P4n=144 | Totaln=552 | p (X2, KW, ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitored days | ||||||

| N | 4079 | 3939 | 3557 | 3922 | 15,497 | |

| Median per patient (IQR) | 18 (27) | 14.5 (29.8) | 16 (25.3) | 21.5 (27.8) | 18 (28) | 0.65 |

| Female genderNo. (%) | 69 (51.5) | 83 (57.6) | 71 (54.6) | 81 (56.3) | 304 (55.1) | 0.76 |

| GAMedian (IQR) | 38 (3) | 37 (6) | 38 (3) | 37 (5.3) | 38 (4) | 0.08 |

| Weight (kg)Median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.7 (1) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.65 (1.12) | 0.14 |

| Surgical interventionNo. (%) | 46 (34.3) | 50 (34.7) | 47 (36.2) | 58 (40.3) | 201 (36.4) | 0.71 |

| Invasive devicesNo. (%) | ||||||

| Central line | 81 (60.4) | 84 (58.3) | 83 (63.8) | 91 (63.2) | 339 (61.4) | 0.77 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 60 (44.8) | 64 (44.4) | 63 (48.5) | 79 (54.9) | 266 (48.2) | 0.26 |

| Urinary tract catheter | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (1.1) | 0.69* |

| TPN | 41 (30.6) | 60 (41.7) | 49 (37.7) | 67 (46.5) | 217 (39.3) | 0.048 |

| No. of patients given antibioticsNo. (%) | 80 (59.7) | 91 (63.2) | 86 (66.2) | 83 (57.6) | 340 (61.6) | 0.48 |

| DeathNo. (%) | 4 (3) | 12 (8.3) | 14 (10.8) | 10 (6.9) | 40 (7.2) | 0.17* |

| % HH complianceMean (SD) | 79.5 (11.9) | 70.7 (16.7) | 63.3 (18.6) | 79.0 (11.8) | 75.0 (5.9) | 0.27** |

KW, Kruskal–Wallis; No, number; IQR, interquartile range; GA, gestational age; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; HCAIs, Healthcare-Associated Infections; HH, hand hygiene.

A mean compliance of 75.0% (SD 5.9) was recorded for 1521 HH opportunities. No trend for this variable (p=0.75) was observed, and there were no significant compliance differences among phases (P1: 79.54% SD 11.19; P2: 70.73% SD 16.72; P3: 63.28% SD 18.62; P4: 79.01 SD 11.77; p=0.27).

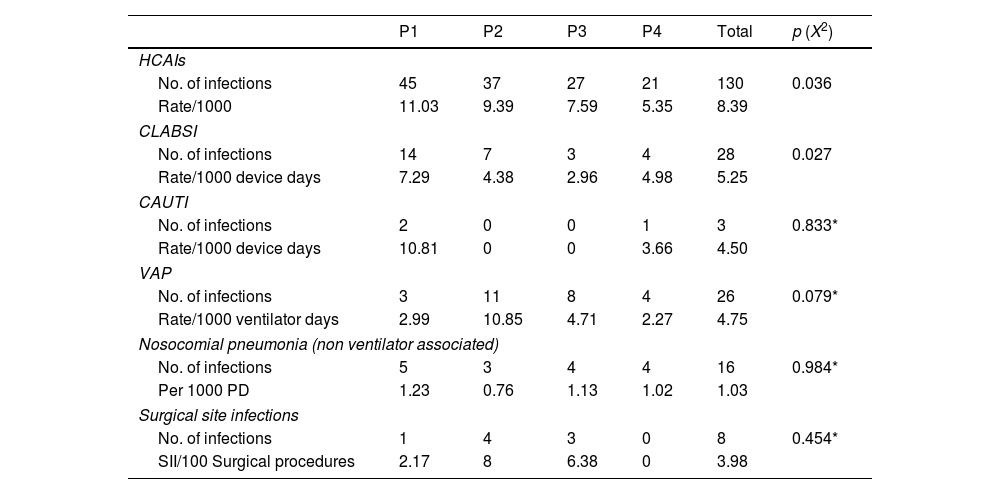

One hundred and thirty HCAIs were recorded (rate 8.39/1000 PD). The HCAI rate fell from 11.03/1000 PD in P1 to 5.35/1000 PD in P4 (p=0.036). Even though the rates for catheter associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) and ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) showed a slight reduction, the reduction was not statistically significant (p>0.079). On the other hand, central line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) was significantly reduced (p=0.027) (Table 2).

HCAIs types for the four study phases.

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | Total | p (X2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAIs | ||||||

| No. of infections | 45 | 37 | 27 | 21 | 130 | 0.036 |

| Rate/1000 | 11.03 | 9.39 | 7.59 | 5.35 | 8.39 | |

| CLABSI | ||||||

| No. of infections | 14 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 28 | 0.027 |

| Rate/1000 device days | 7.29 | 4.38 | 2.96 | 4.98 | 5.25 | |

| CAUTI | ||||||

| No. of infections | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0.833* |

| Rate/1000 device days | 10.81 | 0 | 0 | 3.66 | 4.50 | |

| VAP | ||||||

| No. of infections | 3 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 26 | 0.079* |

| Rate/1000 ventilator days | 2.99 | 10.85 | 4.71 | 2.27 | 4.75 | |

| Nosocomial pneumonia (non ventilator associated) | ||||||

| No. of infections | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 0.984* |

| Per 1000 PD | 1.23 | 0.76 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.03 | |

| Surgical site infections | ||||||

| No. of infections | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0.454* |

| SII/100 Surgical procedures | 2.17 | 8 | 6.38 | 0 | 3.98 | |

HCAIs, healthcare associated infections; PD, patient-days; CLABSI, central line associated blood stream infection; CAUTI, Catheter associated urinary tract infections; VAP, ventilator associated pneumonia.

The analysis showed that UV-C and copper plates proved to provide a significant level of protection against HCAIs (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.30–0.81, p=0.006 P4 vs. P1). This significance was maintained on performing Bonferroni correction test. This protection factor was also found for HCAIs with bacterial isolates (RR=0.33, 95% CI 0.14–0.77, p=0.011 P4 vs P1). Statistical significance for this was also maintained on performing Bonferroni correction (Table 3).

HCAI rates for each phase.

| Phase | Rate | RR (CI 95%) | p | p (X2 for linear trend) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAIs/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 11.03 | 1 | 0.004 | |

| 2 | 9.39 | 0.85 (0.55–1.31) | 0.47 | |

| 3 | 7.59 | 0.69 (0.43–1.11) | 0.123 | |

| 4 | 5.35 | 0.49 (0.30–0.81) | 0.006 | |

| HCAIs without isolates/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 5.15 | 1 | 0.14 | |

| 2 | 6.09 | 1.18 (0.66–2.12) | 0.572 | |

| 3 | 5.06 | 0.98 (0.53–1.84) | 0.957 | |

| 4 | 3.06 | 0.59 (0.29–1.21) | 0.150 | |

| HCAIs with viral isolates/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 0.49 | 1 | 0.801 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0.21 (0.01–4.31) | 0.31 | |

| 3 | 0.28 | 0.57 (0.05–6.32) | 0.65 | |

| 4 | 0.51 | 1.04 (0.15–7.38) | 0.97 | |

| HCAls with bacterial isolates/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 5.39 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| 2 | 3.3 | 0.61 (0.31–1.21) | 0.160 | |

| 3 | 2.25 | 0.42 (0.19–0.94) | 0.034 | |

| 4 | 1.79 | 0.33 (0.14–0.77) | 0.011 | |

| G- bacterial isolate HCAls/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 2.45 | 1 | 0.020 | |

| 2 | 1.78 | 0.73 (0.28–1.90) | 0.51 | |

| 3 | 0.56 | 0.23 (0.05–1.05) | 0.057 | |

| 4 | 0.76 | 0.31 (0.09–1.13) | 0.077 | |

| G- ESBL+bacterial isolate HCAls/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 1.47 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| 2 | 0.76 | 0.68 (0.27–1.71) | 0.35 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0.09 (0.005–1.57) | 0.098 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0.08 (0.005–1.42) | 0.085 | |

| G+bacterial isolate HCAls/1000 PD | ||||

| 1 | 2.70 | 1 | 0.056 | |

| 2 | 1.27 | 0.47 (0.16–1.35) | 0.162 | |

| 3 | 1.69 | 0.63 (0.23–1.70) | 0.355 | |

| 4 | 0.76 | 0.28 (0.08–1.02) | 0.053 | |

HCAIs, healthcare associated infections; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval, G, gram; ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamases *1 was added to do the operation.

A reduction in the rate of HCAIs caused by gram-negative bacteria as well as those caused by ESBL producing bacteria was observed (p=0.020 and p=0.003 respectively). The rate of HCAIs caused by gram-positive bacteria decreased marginally (p=0.056). The rate of HCAIS caused by ESBL producing bacteria decreased from 1.47/1000 PD in P1 to 0/1000 PD in P3 and remained so during P4 (Table 3). No effect was observed for infections caused by respiratory viruses or fungi (p>0.05).

Fig. 1 shows the results obtained, with the implementation of the interventions, in the reduction of HCAIs caused by gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, and in the reduction of HCAIs caused by ESBL. No infections caused by gram-positive MDRO, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) or vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) were detected in the course of the study.

DiscussionHospital surfaces have proven to be risk factors for HCAIs.18 The implementation of both HH and prevention bundles have been shown to reduce HCAI incidence. Nevertheless, HCAIs have continued to occur despite these measures19 and the rate of HCAIs by ESBL+ in newborns seems to be on the rise.6,20 This study yielded relevant findings with respect to the combined use of the proposed strategies, which might contribute to reduce the MDRO epidemic.

Various studies have reported effective reduction of HCAIs with the use of UV-C light.21,22 Most of these studies involved assessment before and after implementation of UV exposure, and some21 showed statistically significant differences. In our study, even though HCAI incidence fell, no significant differences were found with the sole use of UV-C light. Nevertheless, the combined use of UV-C light exposure and CAP placement on frequently used surfaces was associated with a reduction in HCAI with bacteria isolates.

One of the main findings with the introduction of copper treated surfaces to the usual prevention measures and terminal disinfection with UV-C exposure protocols was the existence of a significant reduction, particularly in the rate of gram-negative HCAIs. Moreover, HCAIs by ESBL were no longer detected in new born infants after simultaneous implementation of the three strategies, thus highlighting the importance of environmental control in preventing their genesis and transmission. Although the rate of HCAIs caused by gram-negative bacteria decreased, CAUTIs and VAPs did not decrease significantly. With regard to CAUTI, we attribute the absence of non-significant statistical difference to the small sample size (3 cases) reported during the time of the study. In the case of VAPs, apart from the established risk factors for HCAIs, there are other associated factors, such as gastric aspiration, nasogastric tube, re-intubation, supine body position, thoracic surgery, tracheostomy, among others.23 These factors, that could have intervened in the number of VAPs, were not measured, since it was outside the scope of our study.

With regard to the use of copper, even though various studies have highlighted its efficacy as a method to reduce HCAIs,24,25 very few have been conducted in paediatric population. In Chile, Dessauer et al.10 and in Greece, Efstathiou et al.9 assessed its use in the paediatric intensive care unit and NICU environments respectively. However, these authors just measured bacterial reduction and did not assess its effect on HCAIs as in our study.

According with our results the overall reduction in the rates of HCAIs and the elimination of HCAIs by ESBL+ may be associated with the permanent and non-selective biocidal effect of copper26 when is combined with UVC. The roles played by surfaces and bacterial load as HCAI risk factors has been described.27 Schmidt et al.28 conducted a study where beds, with and without copper, were cleaned and samples for cultures taken. The authors showed that, even though cleaning reduced bed bacterial loads, the copper-treated beds had microbial loads of 85–90% lower than those of control beds. In addition, they proved that microbial load for copper-treated beds reached levels of 2.5–5CFU/cm2 at points of hand contacts and less than 1CFU/cm2 of hospital pathogens29 as proposed by various consensuses. Beds that had been disinfected, but without the application of copper treatment, did not reach these microbiological benchmarks. Although surface sampling and CFU assessment were outside the scope of the present study, HCAIs are known to be multifactorial. Nevertheless, we believe that the interventions performed during the study may have been associated with a reduction in the risk of cross-transmission from one surface to another; and this may explain the HCAI rate reduction observed in the present study.

An interesting finding is that gram-negative HCAI exhibit a significant decrease that was not seen on gram-positive in which just a borderline decrease was seen. Although this could be due to the small sample of HCAI gram-positive, we can explore other explanations. Gram-positive microorganisms are part of the normal flora of the skin and mucous membranes and can be spread just by talking,30 which may limit the control of transmission to inert surfaces. On the other hand, it has been found that some bacteria are resistant to the bactericidal properties of copper, such as Staphylococcus,31 of which both S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidids were present during the study. Another possible explanation would be that the decrease in healthcare-associated infections may have been due to temporary factors and not necessarily to copper or UV light. However, there were no changes in terms of adherence to HH or to the preventive HCAI protocols during the four study periods. We suggest that more and larger studies in population with higher gram-positive prevalence are needed.

While there was a reduction in HCAIs, the number of deaths did not change throughout the four phases of the study. This situation is in accordance with literature reports on mortality impact of the application of the prevention bundles as depicted in the systematic review conducted by Albarquoni.24 Very few of the studies reported in the work of the author addressed mortality, and those that did, reported no differences between patient mortality in hospitals, which implemented copper interventions and those that did not.10,27 Nevertheless, it should be noted that the number of deaths in the present study was low, and based on this, any significant differences could have resulted undetected.

One of the strengths of this study is that it is among those few where intervention implementation was conducted in staggered order. Thus, allowing the measurement of the added effect of human-based preventive actions; such as HH, disinfection and prevention bundles; followed by actions that do not require direct human intervention to act on microbial reservoirs permanently (CAP) or intermittently (UV-C light). The finding that the implementation of these kinds of measures was associated with decreased HCAIs, a problem that had persisted for several years among paediatric patients, strongly suggests the existence of environmental reservoirs that may have been eradicated by such measures.

Another contribution is that compliance with HH and prevention bundles was measured without recording differences between the phases. In addition, both HCAIs and their risk factors were prospectively documented.

As mentioned earlier, this is one of the few studies with a staggered-design implementation strategy. Marik et al. conducted a similar study in the U.S. from 2014 to 2018.32 These authors implemented the use of copper oxide on textiles and found no differences in HCAIs between the control and experimental groups. In the second phase, they introduced copper treatment on high-contact surfaces and observed a reduction from 3.9/1000 PD to 1.3/1000 PD after the intervention. In the present work, copper use on soft surfaces was not implemented; however, it should be noted that the results obtained were similar when the use of CAP and UV-C light intervention were added.

We should mention that the present study had several limitations. The first was that the patients were not randomized and a control group was not established within the NICU. However, it would have been difficult to simultaneously randomize and maintain a control group, given the high risk of handling contamination in a NICU with contiguous incubators as ours. To illustrate, a reduction in bacterial load due to surface CAP would result in a concomitant reduction in the number of bacteria on other surfaces and on the patients, which would have been transmitted indirectly (surface-hand-surface). Logically, this would definitely reduce HCAI risk. Notwithstanding, in this work, other HCAI-associated variables were analyzed and controlled as previously mentioned. Moreover, there were no changes during the course of the study in hospital prevention bundles, cleaning protocols or antibiotic prescription policies. In addition, the staff members providing patient care and their workload did not undergo any change. Also, the nurse-patient ratio remained stable during the four phases. Finally, patient characteristics were similar throughout the study. We should point out that the beneficial use of copper in reducing HCAI-related risk has previously been reported, and it would have been unethical to randomize newborn patients and establish a control group, thus excluding the latter from the potential benefits. As a result, the objective was set to measure the additive effect of both strategies, taking period 1 as the control group, prior to the intervention.

Another limitation is that no samples were taken from healthcare personnel and patients or from surfaces to verify if they were colonized. Carrier screening varies for each type of microorganism. For some, there are guidelines, but they only suggest conducting screening if it's an endemic area or if there have been cases of infections.33,34 For other microorganisms, such as ESBL-producing bacteria, there are no guidelines or sufficient evidence to justify the screening.35,36 Because of this, screening has not been implemented in the hospital, and it was also beyond the scope of the study. Other authors have reported that measuring colonization in the staff who interact with the patients and the patients themselves, before and after the intervention, did no show any differences in the number of carriers.37,38 It would be beneficial to conduct further research on these interventions and carriers.

Regarding surfaces, it would have been very useful to measure the bacterial load on surfaces before and after the intervention. Other studies have analyzed CFUs, resistance mechanisms, and molecular tests to determine if environmental isolates matched bacteria isolated from patients. The aim of this study was to reduce HCAIs, as there is extensive evidence supporting the effect of copper and UV on surfaces. However, in the hospital, there are routine samplings of random surfaces (not part of the study), where we observed a decrease in gram-negative microorganisms in the NICU. It is likely that the decrease in HCAIs was due to a reduced load of microorganisms on surfaces, as previously described.27,39,40 However, we recommend conducting comprehensive studies on environmental reservoirs in this context and their implications in the future.

Even though cost-analysis was not among the scopes of this study, we calculate that the cost of UV-C and CAP would be recovered by eliminating approximately 7 infections. Nevertheless, further studies are required to prove this approximation.

ConclusionCopper treated surfaces, when used in combination with routine disinfection and UV-C light may be an effective strategy to reduce HCAIs in the NICU, including those caused by ESBL producing bacteria. This study sheds light on the importance of eliminating bacteria from high-contact surfaces to reduce MDRO infections in neonate patients. It also stresses the need for further research to determine whether these disinfection techniques should be included in the general guidelines to prevent HCAIs in the NICU and become part of the strategies currently applied to reduce the worldwide epidemic spread of MDRO. Studies, at greater scale, should be undertaken in other types of populations and the cost-benefit assessments should also be addressed.

FinancingThe UV-360 (UVDI) equipment was donated by INIMED. The copper plates were from COINDISSA. None of these companies participated in the design of the study and did not interfere with the analysis or the structure of the manuscript. Apart from these donations, no other type of financial or material support was received. The study was funded by the HIMFG.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We especially thank Salvador Resendiz for his dedication to disinfection. We also thank Victoria Cisneros and Cyril Ndidi Nwoye for translating and reviewing the English version of this article. We thank INIMED and COINDISSA for the donation of the UV-360 equipment and the copper plates respectively. Without these collaborations, this study would not have been possible.