We simulated the impact of implementing different health interventions to improve the HIV continuum of care for people diagnosed, on treatment, and virologically suppressed in Spain for the 2020–2030 period.

MethodsThe model was carried out in four phases involving a multidisciplinary expert panel: (1) literature review; (2) selection/definition of the interventions and their effectiveness; (3) consensus meeting; and (4) development of an analytical decision model to project the impact of implementing/strengthening these interventions to improve the HIV continuum of care, corresponding to 2017–2019 (87% diagnosed, 97% on treatment, 90% with viral suppression), through the creation of different scenarios for 2020–2030. A total of 19 interventions were selected based on expanding the offer of HIV rapid tests and implementing training/peer programmes, electronic alerts, multidisciplinary care, and mHealth, among others. The effectiveness of the interventions was defined by the percentage increases in diagnosis, treatment, and viral suppression after their implementation, targeting the entire population and specific groups at high-risk (men who have sex with men, migrants, female sex workers, transgender people, and people who inject drugs).

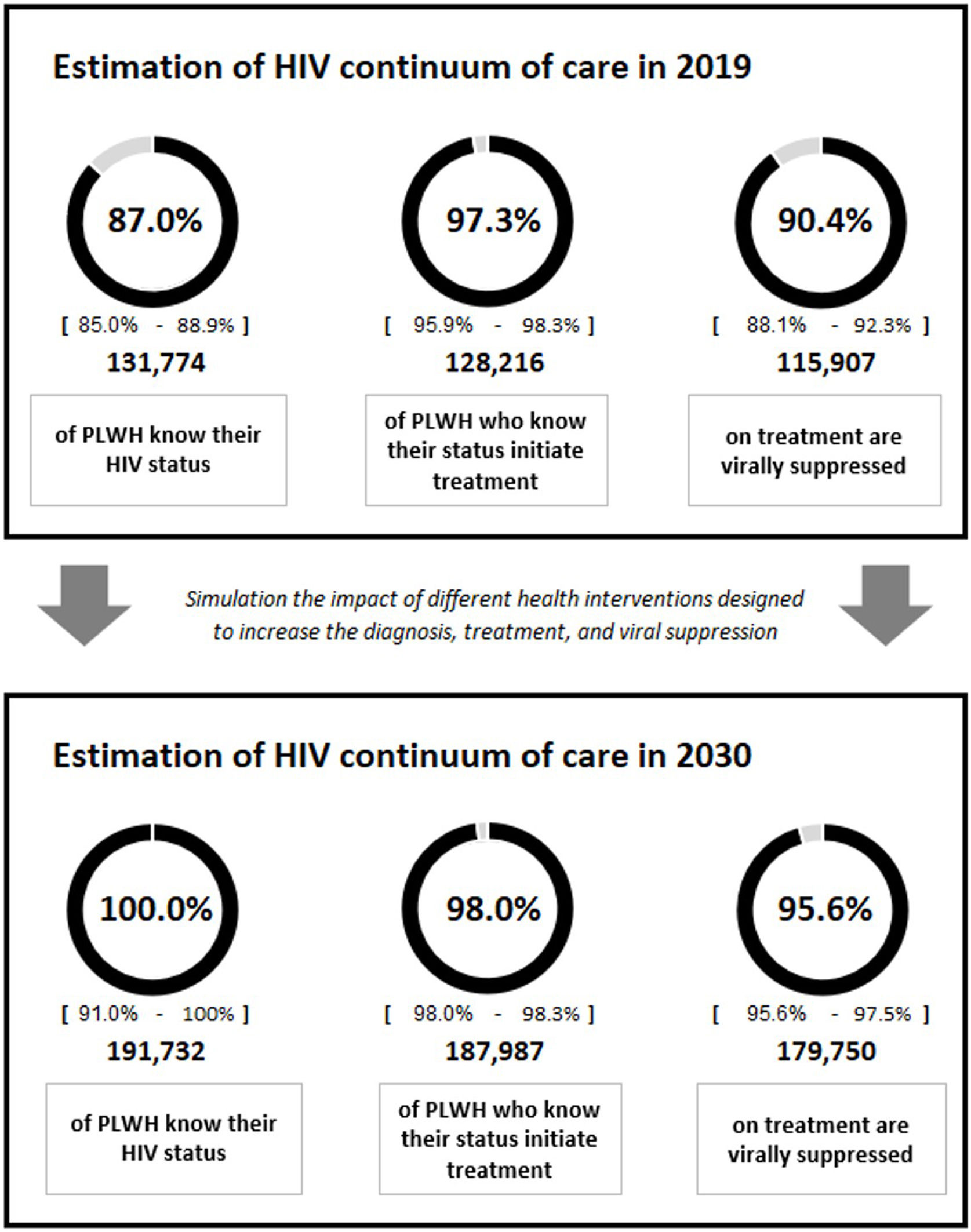

ResultsImplementing eight interventions for diagnosis, three for treatment, and eight for viral suppression for the target populations during 2020–2030 would increase the continuum of care to approximately 100% diagnosed (remaining residual undetectable cases), 98% treated, and 96% virologically suppressed.

ConclusionsPlanification, prioritization, and implementation of selected interventions based on the current HIV continuum of care could allow achievement of the 95-95-95 UNAIDS goals in Spain by 2030.

Simulamos el impacto de la implementación de diferentes intervenciones sanitarias para mejorar la atención continua de las personas diagnosticadas, en tratamiento y con supresión vírica del VIH en España para el período 2020-2030.

MétodosEl modelo se llevó a cabo en 4 fases con la participación de un panel de expertos multidisciplinario: (1) revisión de la literatura médica publicada; (2) selección/definición de las intervenciones y su eficacia; (3) reunión de consenso, y (4) desarrollo de un modelo de toma de decisiones analítico para proyectar el impacto de la implementación/refuerzo de estas intervenciones para mejorar la atención continua de las personas con VIH, correspondiente al período 2017-2019 (87% diagnosticados, 97% en tratamiento y 90% con supresión vírica), a través de la creación de diferentes escenarios para el período 2020-2030. Se seleccionaron un total de 19 intervenciones sobre la base de ampliar la oferta de pruebas rápidas de VIH, y la implementación de programas de formación/entre pares, alertas electrónicas, atención multidisciplinaria y mHealth, entre otras. La efectividad de las intervenciones se definió a partir del porcentaje de incremento en el diagnóstico, tratamiento y supresión vírica tras la implementación, dirigida a toda la población y a grupos específicos de alto riesgo (hombres que mantienen relaciones sexuales con otros hombres, migrantes, trabajadoras sexuales, personas transgénero y personas que consumen drogas inyectables).

ResultadosLa implementación de 8 intervenciones para el diagnóstico, 3 para el tratamiento y 8 para la supresión vírica dirigidas a las poblaciones objetivo durante el período 2020-2030 debería mejorar la atención continua recibida en aproximadamente un 100% de personas diagnosticadas (con un remanente de casos residuales indetectables), un 98% de personas tratadas y un 96% de personas con supresión vírica.

ConclusionesLa planificación, la priorización e implementación de una selección de intervenciones basadas en la atención continua del VIH actual podría permitir alcanzar los objetivos 95-95-95 de ONUSIDA en España para 2030.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) continues to be a major public health issue worldwide. To end the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) proposed meeting 90-90-90 targets by 2020, which include 90% of people living with HIV (PLWH) knowing their HIV status, 90% of people who know their HIV status receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of people on treatment having a suppressed viral load.1 The targets for 2030 have been upgraded to 95-95-95, implying that further efforts are necessary to end this pandemic. Achieving these targets by this date would avoid 21 million AIDS-related deaths and 28 million HIV infections worldwide according to UNAIDS.1

In Spain, is it estimated that 151,387 PLWH,2 with 19253 new cases of HIV diagnosed in 2020, although this figure may be underestimated due to a delay in notification caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the rate of undiagnosed infection remained at 13% (19,613 people).2 Additionally, an estimated 82.7% of transmissions occur through sexual intercourse, which is most frequent among men who have sex with men (MSM) (55.2%), followed by heterosexual transmissions (27.5%).3 Several populations, such as MSM, sex workers, transgender people, people who inject drugs (PWID), and migrants, have a higher risk of acquiring HIV for different reasons. Despite this, there is a delay in diagnosis, except for MSM, mainly due to difficulty to access to healthcare.4

Most PLWH have no symptoms for years; therefore, they may not know their HIV status. Despite a decline in the number of people living with undiagnosed HIV in Spain, the median time from infection to diagnosis is almost 3 years, and as a result, 25–28% of individuals have an advanced (<200CD4 cells/mL) infection at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Early diagnosis of infection allows people to benefit from ART earlier and thus avoid HIV progression.4,6 ART has enabled PLWH to remain with undetectable viral load levels and to reach a life expectancy close to that of the general population, reducing morbidity and mortality and transmission of the virus7; thus, this treatment is clearly an effective strategy.8 However, despite the enormous benefits of ART, a proportion of persons with HIV are unable to fully achieve them because of inadequate therapeutic compliance.9 Thus, poor adherence and resistance to treatment are causes of therapeutic failure and increase the risk of transmitting HIV infection; therefore, knowing the causes is important for correcting them.9

Accordingly, initiatives to increase HIV diagnosis and access to ART and achieve viral suppression must be promoted. Our objective was to evaluate the impact of different health interventions on increases in the percentages of PLWH diagnosed, on treatment, and virologically suppressed, aiming to achieve the UNAIDS targets by 2030 in Spain, through simulations performed by modelling during the 2020–2030 period.

MethodsTo perform the study, a multidisciplinary expert panel was considered (an epidemiologist, infectious diseases specialists, a hospital pharmacist, and health economics consultants), and a four-phase work plan was established: (1) selection and definition of the interventions to be reviewed and their target populations; (2) an exhaustive review of the literature on potential interventions; (3) a consensus meeting or deliberative process; and (4) a modelling process.

In phase 1, based on structured questionnaires and several consensus meetings, the population groups with the highest risk of HIV infection were identified, and for each group, a set of interventions that would potentially impact the HIV continuum of care were defined.

The population groups included were the heterosexual population and key populations such as MSM, migrants, female sex workers (FSWs), transgender people, and PWID. The groups were established according to the mode of HIV acquisition and their incidence rate.10,11

The experts selected and validated a list of relevant interventions focused on increasing the numbers of PLWH diagnosed, on treatment, and with viral suppression for each population group and classified them into three categories: diagnosis, treatment, and strategies aimed at increasing the number of patients with viral suppression. The interventions in the last category were characterized as those to be implemented (i) before starting ART to prepare a patient in a care facility for HIV, (ii) at the beginning of ART based on the choice of ART regimen, and (iii) during ART. Finally, all the experts validated a list of potential interventions that would serve as the basis for the model. In addition, in this phase, the concept of intervention effectiveness was also defined by the percentage increases in people diagnosed with HIV, on treatment among those diagnosed, and with viral suppression among those treated, after its implementation.

In the second phase, an exhaustive review of the published literature was performed to identify information regarding the effectiveness of the interventions selected in the previous phase.14–33 This review was conducted through public database searches with the support of experts.

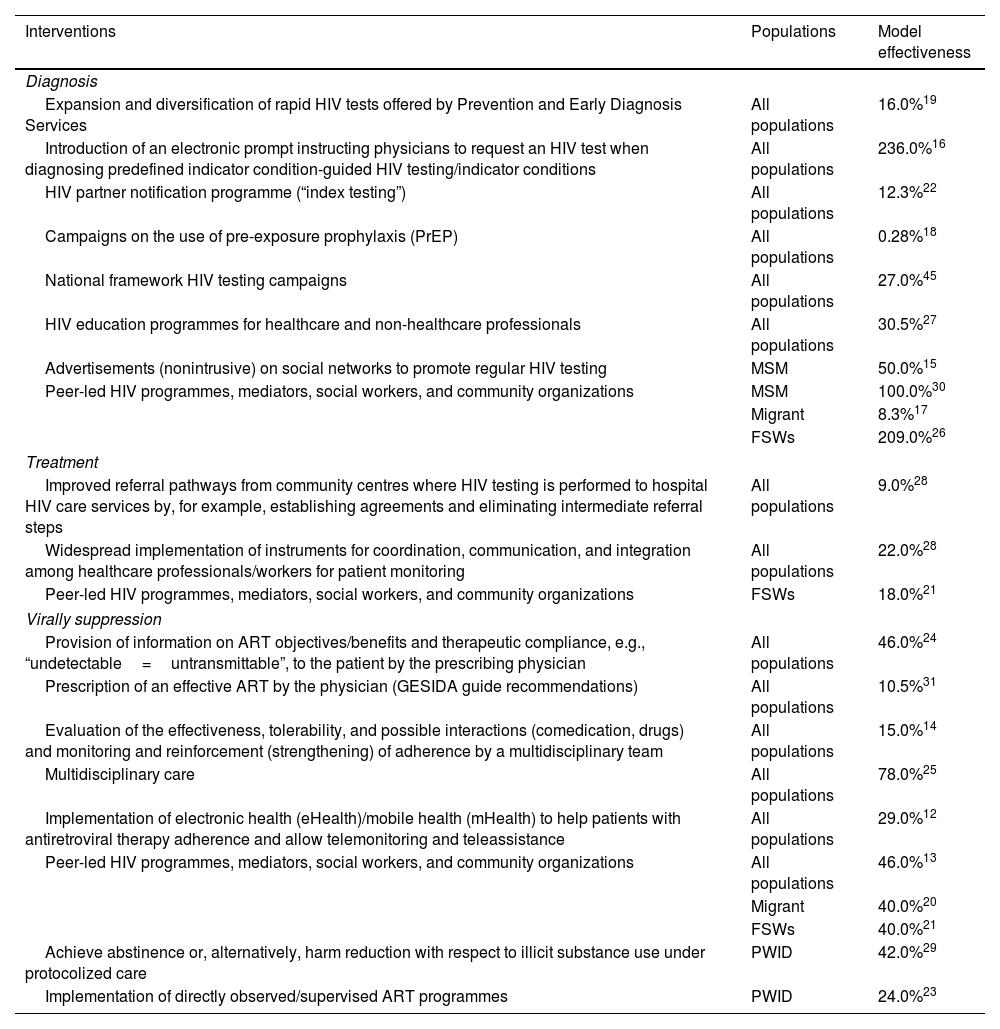

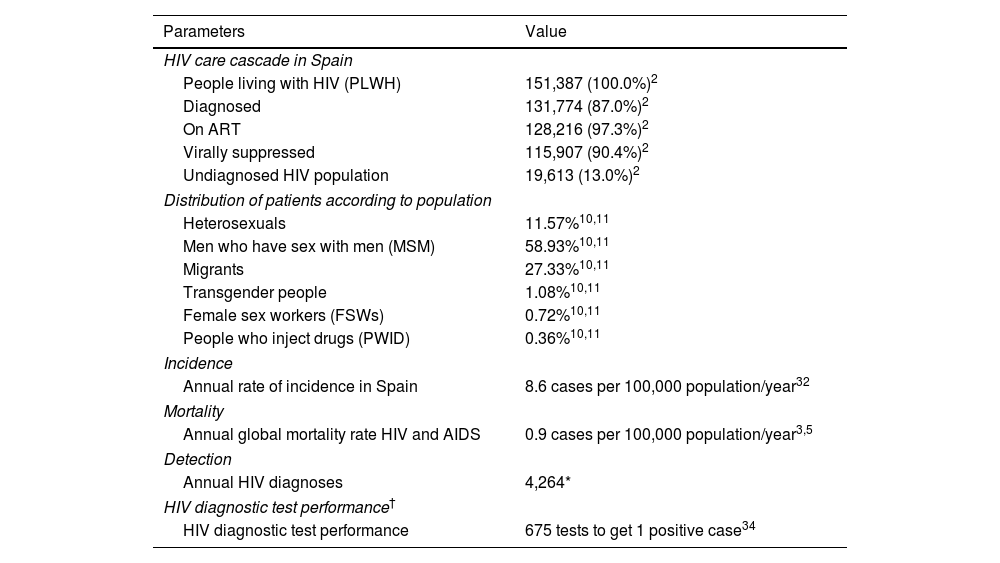

In the third phase, quantifiable interventions with available information on their effectiveness were selected to be included in the analysis. For interventions with data on effectiveness available from different data sources, those with the most robust evidence were chosen. Ultimately, a total of 19 interventions were selected: eight for diagnosis, three for treatment, and eight for viral suppression. All interventions together with their effectiveness data12,27–31 are listed in Table 1. All the additional information for the different actions is expanded in the supplementary material (Table 1S). In the last phase, an analytical decision model was designed with Microsoft Excel to simulate and project the impact of implementing or strengthening the interventions selected in the previous phase on the continuum of HIV care in the 2020–2030 period (Figure 1S). The model allows us to create different scenarios by selecting the interventions and the time in years that they would be active. All the parameters considered in the model were obtained from the literature and were validated by the expert panel (Table 2).

List, classification and effectiveness of the interventions included in the analysis.

| Interventions | Populations | Model effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||

| Expansion and diversification of rapid HIV tests offered by Prevention and Early Diagnosis Services | All populations | 16.0%19 |

| Introduction of an electronic prompt instructing physicians to request an HIV test when diagnosing predefined indicator condition-guided HIV testing/indicator conditions | All populations | 236.0%16 |

| HIV partner notification programme (“index testing”) | All populations | 12.3%22 |

| Campaigns on the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) | All populations | 0.28%18 |

| National framework HIV testing campaigns | All populations | 27.0%45 |

| HIV education programmes for healthcare and non-healthcare professionals | All populations | 30.5%27 |

| Advertisements (nonintrusive) on social networks to promote regular HIV testing | MSM | 50.0%15 |

| Peer-led HIV programmes, mediators, social workers, and community organizations | MSM | 100.0%30 |

| Migrant | 8.3%17 | |

| FSWs | 209.0%26 | |

| Treatment | ||

| Improved referral pathways from community centres where HIV testing is performed to hospital HIV care services by, for example, establishing agreements and eliminating intermediate referral steps | All populations | 9.0%28 |

| Widespread implementation of instruments for coordination, communication, and integration among healthcare professionals/workers for patient monitoring | All populations | 22.0%28 |

| Peer-led HIV programmes, mediators, social workers, and community organizations | FSWs | 18.0%21 |

| Virally suppression | ||

| Provision of information on ART objectives/benefits and therapeutic compliance, e.g., “undetectable=untransmittable”, to the patient by the prescribing physician | All populations | 46.0%24 |

| Prescription of an effective ART by the physician (GESIDA guide recommendations) | All populations | 10.5%31 |

| Evaluation of the effectiveness, tolerability, and possible interactions (comedication, drugs) and monitoring and reinforcement (strengthening) of adherence by a multidisciplinary team | All populations | 15.0%14 |

| Multidisciplinary care | All populations | 78.0%25 |

| Implementation of electronic health (eHealth)/mobile health (mHealth) to help patients with antiretroviral therapy adherence and allow telemonitoring and teleassistance | All populations | 29.0%12 |

| Peer-led HIV programmes, mediators, social workers, and community organizations | All populations | 46.0%13 |

| Migrant | 40.0%20 | |

| FSWs | 40.0%21 | |

| Achieve abstinence or, alternatively, harm reduction with respect to illicit substance use under protocolized care | PWID | 42.0%29 |

| Implementation of directly observed/supervised ART programmes | PWID | 24.0%23 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; FSWs, female sex workers; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drug.

Analysis parameters.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| HIV care cascade in Spain | |

| People living with HIV (PLWH) | 151,387 (100.0%)2 |

| Diagnosed | 131,774 (87.0%)2 |

| On ART | 128,216 (97.3%)2 |

| Virally suppressed | 115,907 (90.4%)2 |

| Undiagnosed HIV population | 19,613 (13.0%)2 |

| Distribution of patients according to population | |

| Heterosexuals | 11.57%10,11 |

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) | 58.93%10,11 |

| Migrants | 27.33%10,11 |

| Transgender people | 1.08%10,11 |

| Female sex workers (FSWs) | 0.72%10,11 |

| People who inject drugs (PWID) | 0.36%10,11 |

| Incidence | |

| Annual rate of incidence in Spain | 8.6 cases per 100,000 population/year32 |

| Mortality | |

| Annual global mortality rate HIV and AIDS | 0.9 cases per 100,000 population/year3,5 |

| Detection | |

| Annual HIV diagnoses | 4,264* |

| HIV diagnostic test performance† | |

| HIV diagnostic test performance | 675 tests to get 1 positive case34 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; FSWs, female sex workers; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MSM, men who have sex with men; PLWH, people living with HIV; PWID, people who inject drugs.

The most recent data available for the continuum of care, which were those for the 2017–2019 period (87% diagnosed, 97% on treatment, 90% with viral suppression),2 were considered in the first year of the simulation. The total population at each stage of the continuum and the number of people included in each population group (heterosexuals, MSM, migrants, FSWs, transgender people, and PWID) were used as a basis to project the continuity of HIV care throughout the time horizon (Table 2).

To estimate the number of new cases of HIV diagnosed annually in clinical practice, the incidence rate and the number of PLWH were considered.32 This value was calculated as the mean number of new diagnoses from 2012 to 2017. In addition, a corrected incidence was calculated, from which we assumed a decrease of 1% associated with the continued use of pre-exposure prophylaxis.33 The annual mortality rate was applied only to the total number of PLWH.32 All these data were obtained from Spanish epidemiological surveillance data sources (Table 2). Likewise, the numbers of patients treated annually and with viral suppression were calculated from the data estimated for the HIV care continuum assuming that 97% of diagnosed patients are on treatment and 90% of those treated are virologically suppressed.

For the interventions whose published effectiveness was measured by the increase in the number of tests (indirect effectiveness), we calculated the ratio between the number of diagnoses and the number of annual HIV tests performed to estimate how much the number of diagnoses would increase with each additional test (test performance). The relationship between these two variables was obtained from a review of the literature (Table 2).34 In addition, we assumed that the effectiveness of the interventions would remain constant while the intervention was implemented (the time associated with the duration of the action after its implementation). On the other hand, in studies in which the effectiveness was given in periods greater than 1 year, it was adjusted to the same period (annual). For this part, a series of assumptions were made: (1) for actions with a duration greater than 1 year, the effectiveness of the action was assumed to be linear; (2) for actions with a duration of less than 1 year, the action was assumed to develop only once a year, thus yielding the annual effectiveness; and (3) in studies without information on the time period, the period was assumed to be 1 year.

Alternative analysisTo assess the uncertainty regarding whether the effectiveness of the interventions persists over time and their impact on the results of the analysis, an alternative analysis was performed considering a linear decrease in effectiveness. Based on the reference studies used, which reported the effects of interventions over different periods and the incidence of new cases detected by population, an annual percentage decrease (29.1%) in the effectiveness of interventions focusing on treatment and viral suppression was estimated.35–37 In the absence of data on decreases in the effectiveness of interventions related to diagnosis, a decrease equal to the undiagnosed fraction (−13%) was assumed.

Qualitative analysisBased on the complexity of initiating and executing all the interventions incorporated in the analysis simultaneously in real-world practice, a prioritization matrix was developed for each group of interventions (diagnosis, treatment, and viral suppression). The prioritization criteria incorporated into the matrix were effectiveness, feasibility (ease of implementation), cost, and acceptability by the target population. Each criterion was weighted according to high priority (a score of 75% out of 100%) and low priority (a score of 25% out of 100%). The matrix was reviewed, validated, and approved by the experts, and its results provided guidance to establish the preference of the most relevant actions to achieve the 95-95-95 goal.

Cost analysisA cost analysis was performed to estimate the economic impact of implementing the interventions. The consumption of resources necessary to carry out the interventions, the unit costs and the total cost of each of them, are listed in Table 2S. For those interventions for which resources are already available in the health system, no additional cost related to their implementation was considered. In addition, the cost of diagnosis (€968.3)38 and treatment (€8788.2)8 associated with the increase in the number of cases were included. All costs included in the analysis were updated to 2019.

ResultsBaseline analysisThe results of the baseline analysis prioritizing all diagnostic interventions for 3 years and the interventions focusing on treatment and viral suppression throughout the time horizon (2020–2030) are included in Table 1. Starting from a current situation results showed that implementation or strengthening of all the interventions from their initiation until 2030 would increase the diagnosis percentage from 87% to approximately 100.0% (with remaining undetectable cases being almost residual), the treatment percentage from 97% to 98.0%, and the viral suppression percentage from 90% to 95.6%, varying versus the initial situation 13%, 1% and 5%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Alternative analysisIn the results for alternative scenarios, when assuming a decrease in effectiveness over time, the percentage of diagnosed patients did not vary from that in the baseline analysis results (100.0%). The percentage of patients treated and with viral suppression decreased from 98.0% to 97.8% and from 95.6% to 94.1%, respectively.

Qualitative analysisThe results of the prioritization matrix evaluated according to the established criteria showed that the criterion with the greatest weight was the effectiveness of the intervention to achieve 95-95-95 objectives, followed by the acceptability criterion and finally the cost. In turn, when evaluating the order of the actions in the three groups, the interventions for the entire population had greater weight than those aimed at specific groups. The most valuable diagnostic interventions were those focused on training health and non-health professionals, electronic alerts, and national campaigns. In the case of treatment, the two interventions aimed at improving referral between care circuits and coordination and communication between professionals had the same score. Among the viral suppression interventions, multidisciplinary care, providing information to patients about treatment benefits, and the prescription of effective ART had the highest scores (Table 3S).

Cost analysisThe estimated economic impact associated with the elected interventions was approximately €14.3 million yearly, €1.5 million of which was associated with diagnosis, €12.5 million with treatment, and €220,506 with the implementation of the interventions.

DiscussionSpain reached 90% for two of the targets proposed by UNAIDS, even exceeding 95% regarding people diagnosed with HIV who are on ART, according to the latest data published in October 20202 (87% diagnosed, 97% on treatment, 90% with viral suppression). To evaluate how the 95-95-95 targets could be achieved in the diagnosis and viral suppression and reinforce the treatment, we built a dynamic model focusing on different interventions among different population groups to increase the number of PLWH diagnosed, receiving ART, and achieving viral suppression.

According to the results of the baseline analysis, the implementation or strengthening actions intended to increase the three targets would help to achieve or even exceed the 95-95-95 goals by 2030. Interventions aimed at health professionals such as training, coordination and communication between them, have a high impact on diagnosis or treatment. In the case of viral suppression, it is more difficult to get interventions that are maintained over time but those aimed at forming multidisciplinary teams or information on ART objectives/benefits to the patients could be the most with greater force. In addition, to evaluate the uncertainty of the model and the variability of the results, an alternative scenario was created considering a decrease in the effectiveness of the interventions over time. The results showed that, as in the baseline analysis, almost all PLWH would be diagnosed; however, the third target would not be achieved (94.1%), necessitating intensification of the actions to ensure that treated patients achieve an undetectable viral load. The economic analysis showed that the cost associated with the interventions would not have a high economic burden, with the highest costs being related to diagnoses and treatment.

On the other hand, UNAIDS is calling on countries to make a global effort and to adopt new and ambitious targets for 2025. Thus, compliance with people-centred targets, especially in vulnerable populations, would help to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. In this sense, adapting the data from our model until 2025, we would obtain similar results to those for 2030 (100% diagnosis, 98% treatment, and 96% viral suppression); that is, performing the interventions proposed in the analysis would allow us to achieve these targets in 2025 and maintain them until 2030.

The major strength of this analysis is the inclusion in the model of enormous amounts of data population, epidemiological and on the interventions to be implemented and the ability to select different values, such as effectiveness and duration in years, to simulate several scenarios in clinical practice, which allowed an assessment of whether the current pace of activity is sufficient to end the pandemic or whether efforts should be focused on certain actions or populations. This flexibility facilitates decision-making. In addition, although the model is theoretical, it was reviewed and validated by a panel of HIV experts who agreed on all the parameters, the included interventions, and their effectiveness, conferring robustness to the obtained results. The model also considered actions currently in practice and their impact on the annual number of patients diagnosed, treated, and with viral suppression associated with different analysis parameters. The incorporation of different population groups based on the number of diagnoses and transmission routes of the disease also confers robustness to the model. The model also allows us to evaluate the economic impact of the interventions. Notably, most interventions would not entail an additional cost because the health system and the community already have the resources to implement them.

The analysis has some limitations discussed below. A limitation is the lack of available evidence on the effectiveness of some actions. To overcome the scarcity of data, some interventions such as community-based HIV initiatives, referral and coordination pathways between centres and counselling, motivational interviewing to patients were combined, creating broad strategies focused on addressing different areas of HIV care and targeting all populations, thus precluding their separation for different groups. Likewise, the possibility of selecting the interventions and their durations led to the assumption of some conservative premises, with synergies that were not considered in the baseline analysis, which was resolved in the qualitative analysis incorporating a prioritization matrix of the actions. Notably, many other relevant actions, for example, the elimination of administrative barriers to access to ART for undocumented migrants,39 were identified that could not be implemented because no evidence was available to quantify their impact, that is, effectiveness data were lacking due to their qualitative nature. Their incorporation into the analysis may have had a greater impact on the results. These actions are listed in Table 4S. Another limitation of the analysis is the lack of updated information on the incidence in certain risk groups. It would be advisable to carry out in-depth epidemiological studies to improve the quality of the evidence of these data. Lastly, another limitation is related to cost analysis. Some premises on the cost derived from the different interventions were included due to the lack and the heterogeneity of information in the published literature.

Regarding the diagnosis of PLWH, the nonavailability of tests, together with the fear of being infected, a misconception about HIV infection, and/or the HIV stigma, may delay the linkage to care, especially in certain population groups. Health and non-health professionals are key to preventing this issue; thus, awareness and training measures must be implemented to create a climate of trust between them and patients.27 Additionally, although HIV is a reportable disease in Spain,40 the effectiveness of active and protocolized communication of all positive HIV tests to health authorities must be increased and reinforced such that patients can be linked to the public health system and to the HIV referral unit.

With regard to treatment access for people diagnosed with HIV, patient clinical management in Spain requires less improvement than other continuum-of-care stages, since we are currently above the 95% target. However, actions that guarantee referral and continuity of care for patients, ensuring that treatment is always prescribed according to current official recommendations, should be emphasized.7 Furthermore, the time from (suspected) diagnosis to consultation with an HIV specialist must be shortened such that ART can be started as soon as possible and to achieve fluid communication between HIV detection points and HIV units.28 The creation of a shared information application among centres would optimize resources and allow detection of losses to follow-up and thus immediate action to link these patients to care.

Multidisciplinary care is also necessary to ensure proper and persistent adherence to treatment.25 Improving access to drugs through home delivery, shared management of drug dispensing between hospital and community pharmacists, and mHealth12 may facilitate therapeutic compliance, especially among pretreated patients. Insufficient information on the benefits of ART causes many people to reject it or not adhere to it continuously. Adherence is closely linked to the type of treatment that the patient is receiving; hence, selection of the optimal ART considering the patient's preferences that provides better quality of life is essential to achieve viral suppression while also accounting for each patient's drug-drug interactions and the presence of non-HIV-related comorbidities.7,9

A fourth 95% target concerns the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of PLWH. Among the factor that determine the HRQoL is mainly the socioeconomic level and the presence of clinical factors for example HCV,41 as well as antiretroviral therapy. Early initiation of ART has a positive impact on the immunological status of HIV-positive individuals by improving CD4 counts with the course of treatment, leading to an increase in quality of life.42,43 Although this fourth target was not included in the scope of our analysis, interventions focusing on early treatment initiation and the introduction of robust treatments with improved efficacy, safety, convenience, and persistence, a high genetic barrier to resistance, a reduced number of drug-drug interactions, and lower bothersome symptoms reported by patients will help improve the adherence and quality of life of patients and consequently achieve this goal.

Finally, advances in treatment and HIV care have improved the HRQoL and life expectancy of PLWH but the social stigma is still present and affects all UNAIDS objectives. The stigmatization of HIV is the main barrier when seeking resources, especially in certain population groups. It is necessary to continue advancing towards the elimination of the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV with the support of institutions and society in order to favour equal treatment and opportunities and social acceptance.39,44

ConclusionsThe planning and prioritization of interventions could favour achievement of the 95-95-95 UNAIDS targets in Spain, increasing the continuum of care to approximately 100% diagnosed, 98% treated, and 96% virologically suppressed during the 2020–2030. Simulation of different scenarios through modelling, being possible to choose interventions focused on the improvement of HIV healthcare, could serve as a tool to evaluate the most effective and efficient interventions and thus increase the percentages of PLWH knowing their serologic status, initiating treatment, and virally suppressed.

FundingThis word was supported by Gilead Sciences.

Conflict of interestsPC reports grants and personal fees from Gilead, MSD, Janssen, ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work.

IJ has received teaching fees from ViiV Healthcare and has been an external evaluator of scientific projects for GILEAD Sciences.

EM has received honoraria for lectures or advisory boards and his institution has received research grants from Gilead, Janssen, MSD and ViiV.

JMM has received honoraria for consultancies and participation as a speaker for Gilead, ViiV, MSD and Janssen.

RDH is an employee of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia, a consultancy firm specializing in the economic evaluation of healthcare interventions that has received unconditional funding from Gilead Sciences.

MAC is an employee of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia, a consultancy firm specializing in the economic evaluation of healthcare interventions that has received unconditional funding from Gilead Sciences.

AC: is an employee of Gilead Sciences Spain. Biopharmaceutical company that has carried out the financing of the project.