Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an eating disorder (ED) characterized by significant weight loss associated with body image distortion and an intense fear of gaining weight, even in the presence of low body weight.1 AN is a multifactorial disorder with considerable variability in clinical presentation, progression, and prognosis, with potential nutritional and organic complications associated with increased mortality. Several and multiple organ complications may arise, primarily stemming from dietary restriction and/or compensatory behaviors. GI complications, such as constipation or abdominal distension, are common and generally solve with nutritional restoration. However, unusual but potentially severe complications must also be considered in the evaluation of these patients.

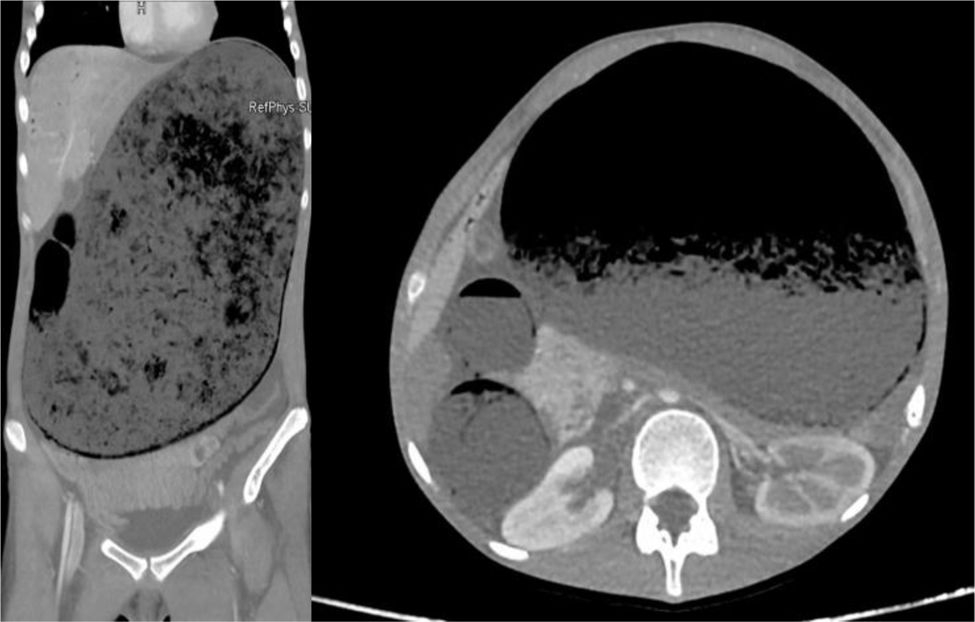

This is the case report of a 16-year-old girl with a 2-year history of restrictive AN, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, and low bone mineral density for her age (z-score -1.6) with a femoral fracture. She was admitted to general surgery after being transferred from the emergency department of a different center with a 3-day history of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension in the context of intestinal obstruction. Lab test results revealed elevated venous lactate levels at 4.2mmol/L (normal range [NR] 0.5–2.2mmol/L), amylase at 730 U/L (NR 30.0–118.0 U/L), and creatine kinase at 177 U/L (NR 24.0–170.0 U/L), without electrolyte, hematological, or coagulation abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed significant gastric and dilation of the first part of the duodenum due to a bezoar, with gastric and duodenal ischemia due to extrinsic aortic compression and hypoperfusion of the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, left kidney, jejunal, and ileal loops, as well as extrinsic urinary tract compression with right pyelocaliectasis (Fig. 1). According to the ED, before the medical complication leading to hospitalization, the patient had not attended follow-ups in recent months and reported increased physical activity along with progressively reduced dietary intake, primarily eating large amounts of fruit (10 pieces/day). At admission, her weight was 41.8kg for a height of 1.56m (body mass index [BMI], 17kg/m2; mean BMI percentage [mBMI%], 82.4%).

Initial conservative treatment included nasogastric tube aspiration, chemical dissolution of the bezoar, and parenteral nutrition (PN) for 25 days. After resolution of intestinal obstruction, oral intake was resumed with a pureed diet and oral nutritional supplements (ONS). Despite adjusting nutritional requirements, the patient experienced weight loss, reaching a nadir of 33.5kg (BMI, 13.7kg/m2; mBMI%, 66.3%). She was transferred to psychiatry for continued ED treatment. During progression to an easily digestible soft diet, she developed sialorrhea and the sensation of a foreign body in her esophagus. Oral endoscopy revealed erosive gastropathy and fibrotic areas, with decreased gastric distensibility and esophageal stenosis due to prior ischemia. Given these findings, a pureed diet and liquid ONS were maintained, along with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). During her psychiatric hospitalization, the patient achieved progressive weight gain without refeeding syndrome symptoms, reaching a BMI at discharge of 16kg/m2. Outpatient follow-up after six months of PPI treatment showed improvement in esophageal stenosis and appropriate progression to a solid diet, although weight stagnation persisted (BMI at the last visit 16kg/m2) due to poor adherence to the prescribed nutritional plan.

A bezoar is an accumulation of indigestible material in the GI tract. Gastric bezoars are rare and cause nonspecific symptoms (vomiting, loss of appetite, weight loss, and abdominal pain), being an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction. They are categorized according to their composition, with phytobezoars being the most common, formed from the ingestion of insoluble plant fiber,2 as in the case described.

The occurrence of intestinal obstruction due to bezoar is rare and poorly reported in AN. Symptom overlap between bezoar and the ED per se can obscure and delay diagnosis. Literature describes 4 cases of bezoar in patients with AN (2 cases presented with intestinal obstruction, 1 resolved with emergency surgery and 1 with conservative therapy).3 Case #3 involved a patient with purging AN who, during hospitalization, experienced vomiting with bezoar-like contents confirmed solved by endoscopy without further treatment.4 Case #4 involved a patient with trichotillomania admitted for suspected restrictive AN (BMI=15kg/m2) who, during dietary progression, developed intestinal obstruction requiring emergenct surgery, revealing a trichobezoar.5

The best imaging modality for initial bezoar diagnosis is CT. Although upper endoscopy can be used for definitive diagnosis, it should not be performed in cases of obstruction.2 Phytobezoar treatment may be conservative using chemical dissolution or endoscopic/surgical approach based on severity. In the described case, conservative therapy used Coca-Cola® as a solvent with gastric lavage through a nasogastric tube. A systematic review of 24 observational studies with 46 patients showed Coca-Cola® administration resolved phytobezoars in 50% of cases.6

In the evaluation of GI symptoms in AN patients, the potential emergence of rare but severe complications requiring specific treatment must be considered.

FundingNone declared.