Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) is a prevalent chronic disease with major complications. Primary care (PC) plays a crucial role in the management of this disease.

ObjectivesTo evaluate the organization and resources available in PC for the care of patients with DM2 in Spain.

Material and methodsDescriptive, cross-sectional, observational study in 65 health centers (HC) selected by opportunistic sampling. Data were collected through a structured survey.

ResultsHalf of the HCs have a diabetes referent, two thirds have specific protocols and almost 90% involve nurses in diabetes education. Access to non-mydriatic retinography is limited (38.5%) and its interpretation varies. Diabetic foot examination is mainly performed by nurses (47.7%) and there is the possibility of referral to vascular surgery or specialized units in most cases. The most frequent analytical tests are the HbA1c every 6 mo (67.7%). 63.1% of the HCs can perform telematic consultations to hospital specialists and most of them have access to patients’ medical records at the hospital. Significant variations are observed in some aspects between autonomous communities.

ConclusionsCare for patients with DM2 in PC in Spain is uneven and presents opportunities for improvement. Comprehensive diabetes care in PC needs to be strengthened, including the training of professionals, the implementation of protocols and the provision of adequate resources. Measures are needed to reduce variations in care between autonomous communities.

La diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) es una enfermedad crónica prevalente con importantes complicaciones. La atención primaria (AP) juega un papel crucial en el manejo de esta enfermedad.

ObjetivosEvaluar la organización y los recursos disponibles en la AP para la atención de pacientes con DM2 en España.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo, transversal y observacional en 65 centros de salud (CS) seleccionados mediante muestreo oportunista. Se recopilaron datos a través de una encuesta estructurada.

ResultadosLa mitad de los CS cuentan con un referente de diabetes, dos tercios tienen protocolos específicos y casi el 90% involucra a enfermería en la educación diabetológica. El acceso a retinografías no midriáticas es limitado (38,5%) y su interpretación varía. La exploración del pie diabético la realiza principalmente enfermería (47,7%) y existe la posibilidad de derivación a Cirugía Vascular o unidades especializadas en la mayoría de los casos. Las pruebas analíticas más frecuentes son la HbA1c cada 6 meses (67,7%). El 63,1% de los CS pueden realizar consultas telemáticas con especialistas hospitalarios y la mayoría tienen acceso a la historia clínica de los pacientes en el hospital. Se observan variaciones significativas en algunos aspectos entre comunidades autónomas.

ConclusionesLa atención a pacientes con DM2 en AP en España es desigual y presenta oportunidades de mejora. Se requiere fortalecer la atención integral de la diabetes en AP, incluyendo la formación de profesionales, la implementación de protocolos y la dotación de recursos adecuados. Se necesitan medidas para reducir las variaciones en la atención entre comunidades autónomas.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases, causing approximately 2 million deaths each year.1 It affects around 537 million people, and its prevalence is estimated to reach 783 million by 2045.2

In Spain, the estimated prevalence of T2DM in 2012 was 13.8%, with 6% of cases being undiagnosed.3 The 2007 National Health System Diabetes Strategy states that this disease is primarily diagnosed and managed in primary care (PC), with shared care involving endocrinology or internal medicine depending on the severity and complexity of the case.4

According to the most widely used Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) on the management of T2DM in Spain,5,6 the goals of T2DM management focus on achieving good glycemic control, individualizing target glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels based on age, disease duration, and patient comorbidities, as well as detecting and preventing complications. Ideally, a diagnosed and stable patient should have biannual appointments with their family doctor and between 2 and 4 appointments with their nurse. Each year, lifestyle habits should be reviewed, microvascular and macrovascular complications should be screened, along with psychosocial and cognitive issues, sleep disorders, toxic habits, and treatment should be reassessed. HbA1c and lipid profiles should be evaluated twice a year, while the albumin/creatinine ratio and glomerular filtration rate should be checked annually. Cardiovascular risk should be calculated once a year, an electrocardiogram should be performed, and the vaccination schedule should be updated. Quarterly, blood pressure, heart rate, weight, and body mass index should be assessed, along with screening for hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia symptoms and reevaluating diabetes education.5 These recommendations should be individualized.

The 2012 update of the National Health System Diabetes Strategy promotes coordination between care levels and specialties, as well as the implementation of specific protocols for T2DM treatment and follow-up in autonomous communities.7

Overall, the referral criteria to endocrinology recommended by the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs CPG include: suspicion of specific types of diabetes (genetic, exocrine pancreatic diseases, and endocrinopathies), patients younger than 40 years with possible type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) at diagnosis, pregnancy in women with diabetes or gestational diabetes, and chronic poor metabolic control despite therapeutic modifications. There are also referral criteria to other specialties in case of disease complications.8

In summary, diabetes care should be multidisciplinary. The approach in PC should be shared between medicine and nursing and should interact with other care levels for comprehensive management. However, in Spain, health care is managed independently in each autonomous community, so protocols may vary depending on available resources and recommendations in each region. The aim of this study is to describe how T2DM care is organized in PC in Spain and analyze the main differences across regions.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional, and observational, study on a representative sample of members of the Spanish Diabetes Society (SED) responsible for diabetes in primary care centers (PCCs) across autonomous communities.

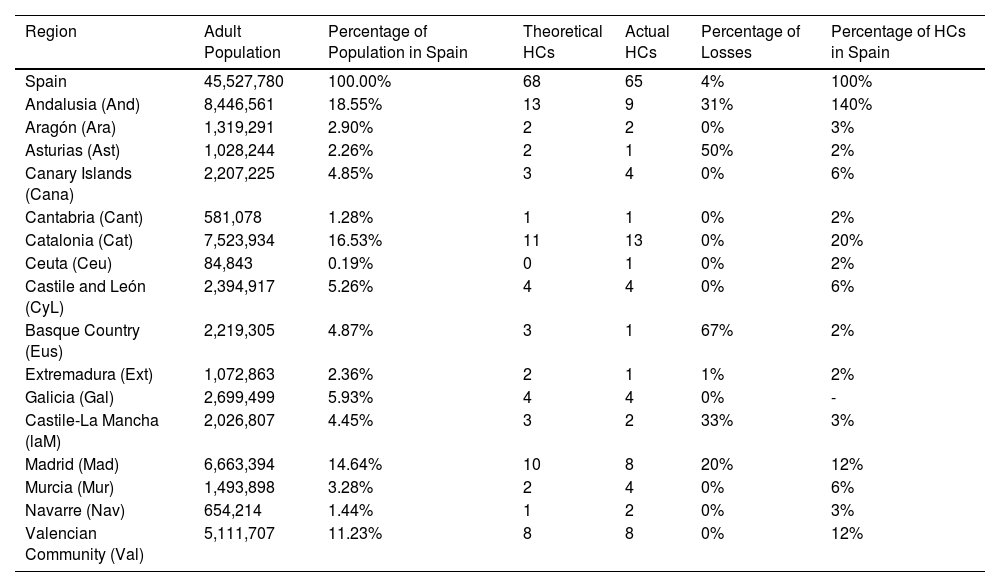

The sample size was based on the GranMo calculator (https://www.datarus.eu/aplicaciones/granmo/) and calculated using the formula for a large population, assuming an estimated T2DM prevalence of 14%, a 95% confidence interval, and a 10% precision. This calculation indicated the need to include at least 57 PCCs. To account for potential refusals, the sample size was increased by 20%, reaching a total of 65 PCCs. The study population was selected through opportunistic sampling, collecting data from 65 participating PCCs, both rural and urban, that voluntarily agreed to participate in the study during 2021. This approach was justified by the need to quickly access data from available centers at the time of the study, although we acknowledge potential limitations in representativeness due to voluntary participation. Efforts were made to ensure territorial representativeness so that the sample adequately described the sociodemographic and clinical profile of T2DM patients in Spain. The participation of each autonomous community is shown in Table 1.

Sample description.

| Region | Adult Population | Percentage of Population in Spain | Theoretical HCs | Actual HCs | Percentage of Losses | Percentage of HCs in Spain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 45,527,780 | 100.00% | 68 | 65 | 4% | 100% |

| Andalusia (And) | 8,446,561 | 18.55% | 13 | 9 | 31% | 140% |

| Aragón (Ara) | 1,319,291 | 2.90% | 2 | 2 | 0% | 3% |

| Asturias (Ast) | 1,028,244 | 2.26% | 2 | 1 | 50% | 2% |

| Canary Islands (Cana) | 2,207,225 | 4.85% | 3 | 4 | 0% | 6% |

| Cantabria (Cant) | 581,078 | 1.28% | 1 | 1 | 0% | 2% |

| Catalonia (Cat) | 7,523,934 | 16.53% | 11 | 13 | 0% | 20% |

| Ceuta (Ceu) | 84,843 | 0.19% | 0 | 1 | 0% | 2% |

| Castile and León (CyL) | 2,394,917 | 5.26% | 4 | 4 | 0% | 6% |

| Basque Country (Eus) | 2,219,305 | 4.87% | 3 | 1 | 67% | 2% |

| Extremadura (Ext) | 1,072,863 | 2.36% | 2 | 1 | 1% | 2% |

| Galicia (Gal) | 2,699,499 | 5.93% | 4 | 4 | 0% | - |

| Castile-La Mancha (laM) | 2,026,807 | 4.45% | 3 | 2 | 33% | 3% |

| Madrid (Mad) | 6,663,394 | 14.64% | 10 | 8 | 20% | 12% |

| Murcia (Mur) | 1,493,898 | 3.28% | 2 | 4 | 0% | 6% |

| Navarre (Nav) | 654,214 | 1.44% | 1 | 2 | 0% | 3% |

| Valencian Community (Val) | 5,111,707 | 11.23% | 8 | 8 | 0% | 12% |

HC: Health Centers.

The study was approved by Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia Ethics Committee for Drug Research (2024/192).

Study variablesThe survey designed specifically for this study consisted of 23 questions, structured into the following sections:

- 1

Care and organizational aspects:

- o

Location and population: For each PCC, the location, setting (urban or rural), and population size served were determined.

- o

Diabetes reference and diabetes education: The presence of a diabetes reference in the PCC and the practice of diabetes education were evaluated.

- o

Protocols and care pathways: The existence of an internal protocol and/or care pathway in the PCC was investigated.

- o

Continuing education: The continuing education of health care professionals in diabetes was analyzed.

- o

Multidisciplinary committee: The presence of a multidisciplinary committee dedicated to diabetes in the health care area was investigated.

- o

Access to patient lists and data: The ability to access patient lists and data at the organizational level was explored.

- o

- 2

Access to examinations in the PCC:

- o

Retinography: The possibility of performing retinography and its interpretation in the PCC was evaluated.

- o

Laboratory tests: The option to request all necessary laboratory tests and their frequency was investigated.

- o

Diabetic foot care: The care for diabetic foot and referral options available in each PCC were examined.

- o

- 3

Primary/Specialized referrals:

- o

Reasons for referral: The main reasons for referral from PC to hospital care were investigated.

- o

Teleconsultations: The possibility of conducting teleconsultations with other care levels was explored.

- o

Access to health records: The ability to access hospital medical records and receive reports with referral results was evaluated.

- o

Data were collected by researchers in an electronic data collection notebook (DCN), specifically designed for this study.

Initial data analysis was based on descriptive statistics. Measures of central tendency were calculated using means and medians, while measures of dispersion were calculated using standard deviation and interquartile ranges. For qualitative variables, percentages and confidence intervals were used.

Comparative inferential statistics were performed using the Mann-Whitney U or Friedman tests for continuous variables and analysis of variance. For categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. Differences were calculated across samples from different autonomous communities.

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS® statistical package, version 23.

ResultsResponses from 65 PCCs distributed across the country were analyzed (Table 1). The care provided by PC to people with diabetes was structured into 3 sections:

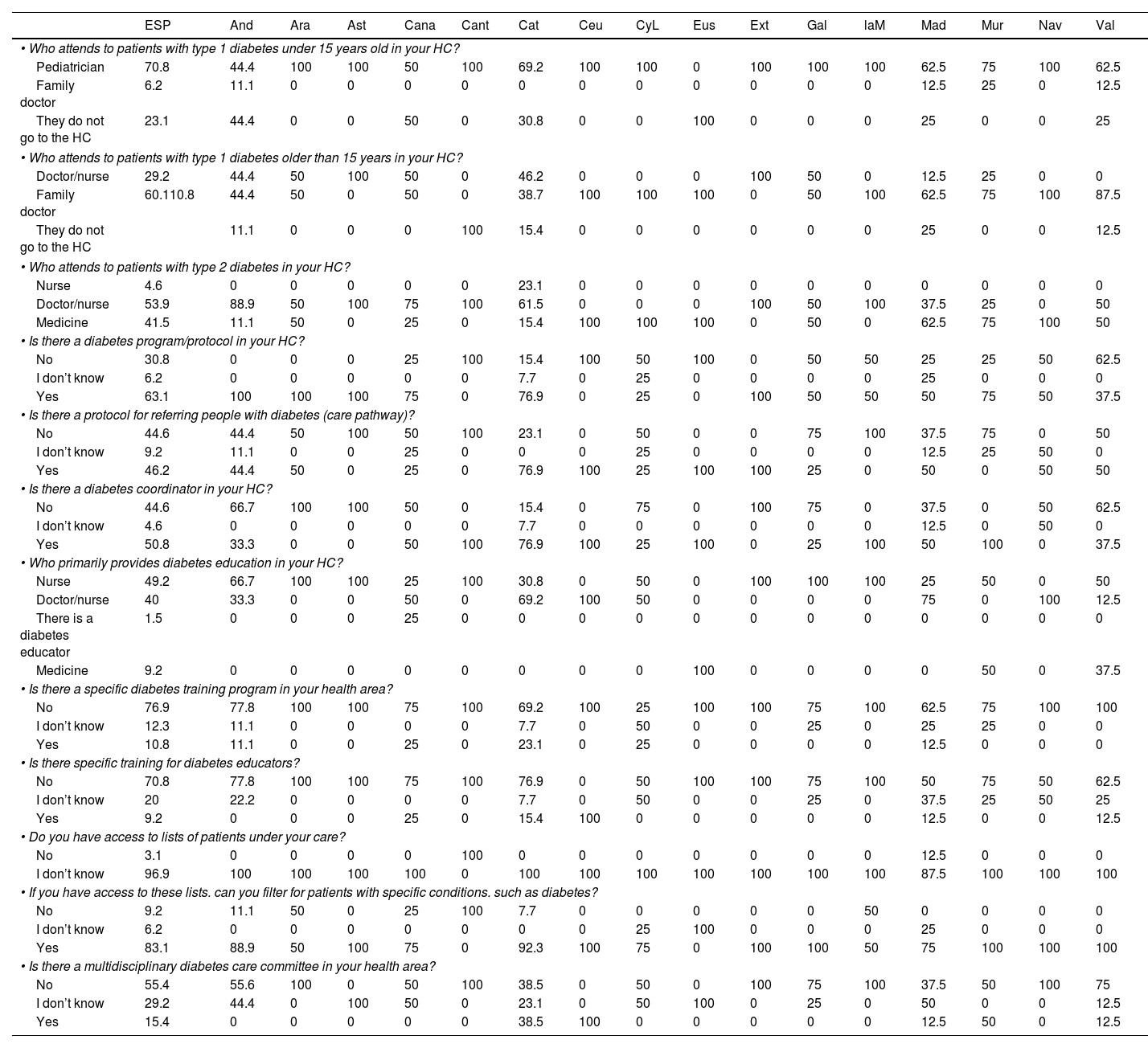

Care and Organizational Aspects (Table 2)- o

Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) are mostly treated in specialized services (hospital or outpatient). However, when they visit the PCC, those younger than 15 years are primarily seen by a pediatrician, while those older than 15 years are seen by a family doctor.

Table 2.Health care and organizational aspects of primary care in Spain by autonomous communities.

ESP And Ara Ast Cana Cant Cat Ceu CyL Eus Ext Gal laM Mad Mur Nav Val • Who attends to patients with type 1 diabetes under 15 years old in your HC? Pediatrician 70.8 44.4 100 100 50 100 69.2 100 100 0 100 100 100 62.5 75 100 62.5 Family doctor 6.2 11.1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 12.5 25 0 12.5 They do not go to the HC 23.1 44.4 0 0 50 0 30.8 0 0 100 0 0 0 25 0 0 25 • Who attends to patients with type 1 diabetes older than 15 years in your HC? Doctor/nurse 29.2 44.4 50 100 50 0 46.2 0 0 0 100 50 0 12.5 25 0 0 Family doctor 60.110.8 44.4 50 0 50 0 38.7 100 100 100 0 50 100 62.5 75 100 87.5 They do not go to the HC 11.1 0 0 0 100 15.4 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 0 0 12.5 • Who attends to patients with type 2 diabetes in your HC? Nurse 4.6 0 0 0 0 0 23.1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Doctor/nurse 53.9 88.9 50 100 75 100 61.5 0 0 0 100 50 100 37.5 25 0 50 Medicine 41.5 11.1 50 0 25 0 15.4 100 100 100 0 50 0 62.5 75 100 50 • Is there a diabetes program/protocol in your HC? No 30.8 0 0 0 25 100 15.4 100 50 100 0 50 50 25 25 50 62.5 I don’t know 6.2 0 0 0 0 0 7.7 0 25 0 0 0 0 25 0 0 0 Yes 63.1 100 100 100 75 0 76.9 0 25 0 100 50 50 50 75 50 37.5 • Is there a protocol for referring people with diabetes (care pathway)? No 44.6 44.4 50 100 50 100 23.1 0 50 0 0 75 100 37.5 75 0 50 I don’t know 9.2 11.1 0 0 25 0 0 0 25 0 0 0 0 12.5 25 50 0 Yes 46.2 44.4 50 0 25 0 76.9 100 25 100 100 25 0 50 0 50 50 • Is there a diabetes coordinator in your HC? No 44.6 66.7 100 100 50 0 15.4 0 75 0 100 75 0 37.5 0 50 62.5 I don’t know 4.6 0 0 0 0 0 7.7 0 0 0 0 0 0 12.5 0 50 0 Yes 50.8 33.3 0 0 50 100 76.9 100 25 100 0 25 100 50 100 0 37.5 • Who primarily provides diabetes education in your HC? Nurse 49.2 66.7 100 100 25 100 30.8 0 50 0 100 100 100 25 50 0 50 Doctor/nurse 40 33.3 0 0 50 0 69.2 100 50 0 0 0 0 75 0 100 12.5 There is a diabetes educator 1.5 0 0 0 25 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Medicine 9.2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 50 0 37.5 • Is there a specific diabetes training program in your health area? No 76.9 77.8 100 100 75 100 69.2 100 25 100 100 75 100 62.5 75 100 100 I don’t know 12.3 11.1 0 0 0 0 7.7 0 50 0 0 25 0 25 25 0 0 Yes 10.8 11.1 0 0 25 0 23.1 0 25 0 0 0 0 12.5 0 0 0 • Is there specific training for diabetes educators? No 70.8 77.8 100 100 75 100 76.9 0 50 100 100 75 100 50 75 50 62.5 I don’t know 20 22.2 0 0 0 0 7.7 0 50 0 0 25 0 37.5 25 50 25 Yes 9.2 0 0 0 25 0 15.4 100 0 0 0 0 0 12.5 0 0 12.5 • Do you have access to lists of patients under your care? No 3.1 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 12.5 0 0 0 I don’t know 96.9 100 100 100 100 0 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 87.5 100 100 100 • If you have access to these lists. can you filter for patients with specific conditions. such as diabetes? No 9.2 11.1 50 0 25 100 7.7 0 0 0 0 0 50 0 0 0 0 I don’t know 6.2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 100 0 0 0 25 0 0 0 Yes 83.1 88.9 50 100 75 0 92.3 100 75 0 100 100 50 75 100 100 100 • Is there a multidisciplinary diabetes care committee in your health area? No 55.4 55.6 100 0 50 100 38.5 0 50 0 100 75 100 37.5 50 100 75 I don’t know 29.2 44.4 0 100 50 0 23.1 0 50 100 0 25 0 50 0 0 12.5 Yes 15.4 0 0 0 0 0 38.5 100 0 0 0 0 0 12.5 50 0 12.5 All values express percentages of the total in the column.

And: Andalusia; Ara: Aragon; Ast: Asturias; Cana: Canary Islands; Cant: Cantabria; Cat: Catalonia; Ceu: Ceuta; CyL: Castile and León; CS: health center; DM: diabetes mellitus; Eus: Basque Country; Ext: Extremadura; Gal: Galicia; laM: La Mancha; Mad: Madrid; Mur: Murcia; Nav: Navarre; Val: Valencian Community.

- o

Approximately half (50.8%) of PCCs have a diabetes reference within the center. A total of 63.1% have a specific diabetes protocol/program, and 46.2% have well-defined referral criteria to the secondary level (care pathway).

- o

Diabetes education involves PCC nurses in 89.2% of cases, while doctors participate in a coordinated manner in 49.2% of cases. However, only 10.8% of PCCs have a structured diabetes education program.

- o

Almost all professionals can access patient lists, and in 83.1% of cases, they can also access specific data on patient variables and characteristics.

- o

These figures may vary significantly between autonomous communities (Table 2).

- o

- o

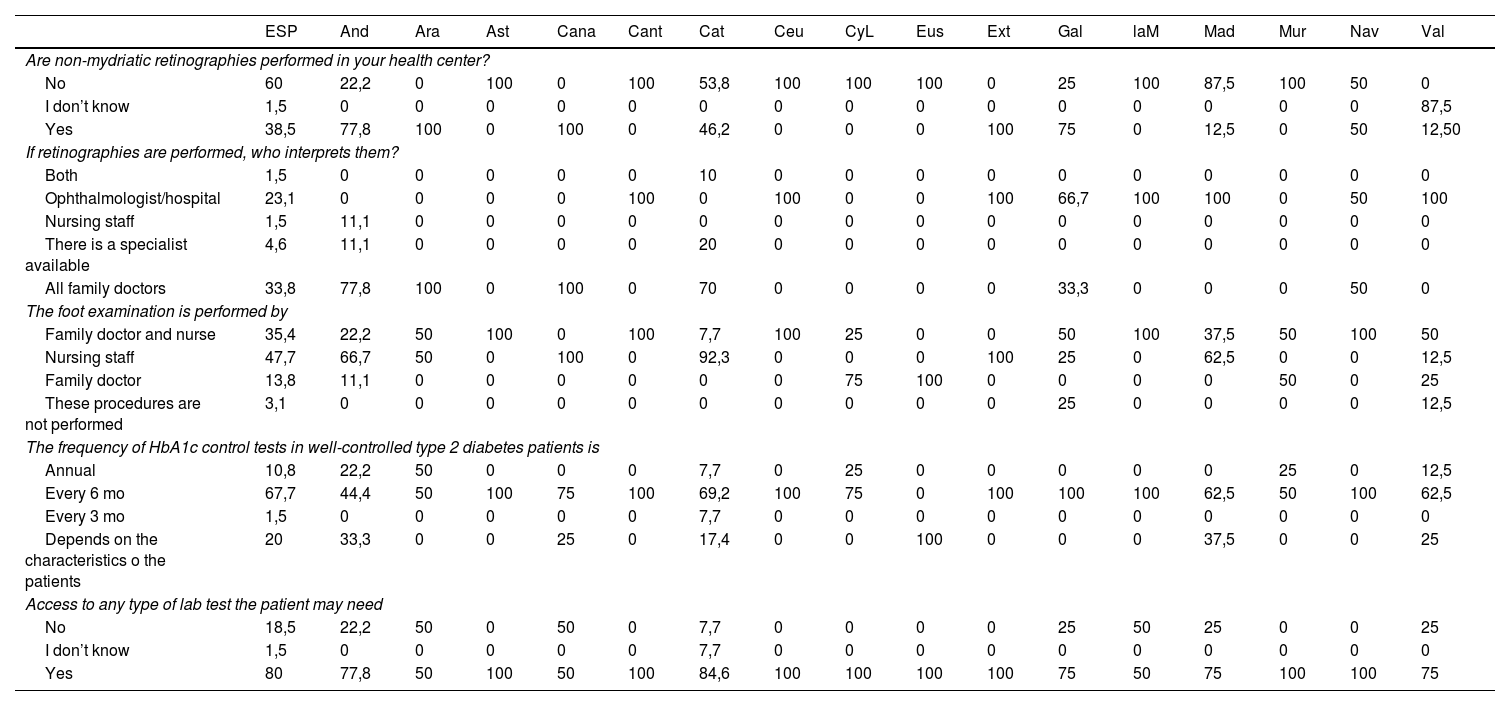

Only 38.5% of centers perform non-mydriatic retinography. In 52.4% of cases, these are interpreted by family doctors, while in 35.7% by ophthalmologists.

Table 3.Access to examinations in the health center.

ESP And Ara Ast Cana Cant Cat Ceu CyL Eus Ext Gal laM Mad Mur Nav Val Are non-mydriatic retinographies performed in your health center? No 60 22,2 0 100 0 100 53,8 100 100 100 0 25 100 87,5 100 50 0 I don’t know 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 87,5 Yes 38,5 77,8 100 0 100 0 46,2 0 0 0 100 75 0 12,5 0 50 12,50 If retinographies are performed, who interprets them? Both 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Ophthalmologist/hospital 23,1 0 0 0 0 100 0 100 0 0 100 66,7 100 100 0 50 100 Nursing staff 1,5 11,1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 There is a specialist available 4,6 11,1 0 0 0 0 20 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 All family doctors 33,8 77,8 100 0 100 0 70 0 0 0 0 33,3 0 0 0 50 0 The foot examination is performed by Family doctor and nurse 35,4 22,2 50 100 0 100 7,7 100 25 0 0 50 100 37,5 50 100 50 Nursing staff 47,7 66,7 50 0 100 0 92,3 0 0 0 100 25 0 62,5 0 0 12,5 Family doctor 13,8 11,1 0 0 0 0 0 0 75 100 0 0 0 0 50 0 25 These procedures are not performed 3,1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 0 0 0 0 12,5 The frequency of HbA1c control tests in well-controlled type 2 diabetes patients is Annual 10,8 22,2 50 0 0 0 7,7 0 25 0 0 0 0 0 25 0 12,5 Every 6 mo 67,7 44,4 50 100 75 100 69,2 100 75 0 100 100 100 62,5 50 100 62,5 Every 3 mo 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 7,7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Depends on the characteristics o the patients 20 33,3 0 0 25 0 17,4 0 0 100 0 0 0 37,5 0 0 25 Access to any type of lab test the patient may need No 18,5 22,2 50 0 50 0 7,7 0 0 0 0 25 50 25 0 0 25 I don’t know 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 7,7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Yes 80 77,8 50 100 50 100 84,6 100 100 100 100 75 50 75 100 100 75 All values express percentages of the total in the column.

And: Andalusia; Ara: Aragon; Ast: Asturias; Cana: Canary Islands; Cant: Cantabria; Cat: Catalonia; Ceu: Ceuta; CyL: Castile and León; CS: health center; DM: diabetes mellitus; Eus: Basque Country; Ext: Extremadura; Gal: Galicia; laM: La Mancha; Mad: Madrid; Mur: Murcia; Nav: Navarre; Val: Valencian Community.

- o

Foot examinations are routinely performed by nurses in 47.7% of cases and by both nurses and doctors in 35.4% of cases. In case of diabetic foot complications, most centers report the possibility of referral to vascular surgery (46.2%) or specific diabetic foot units (35.4%). Alarmingly, 3.1% of PCCs report being unable to refer these patients.

- o

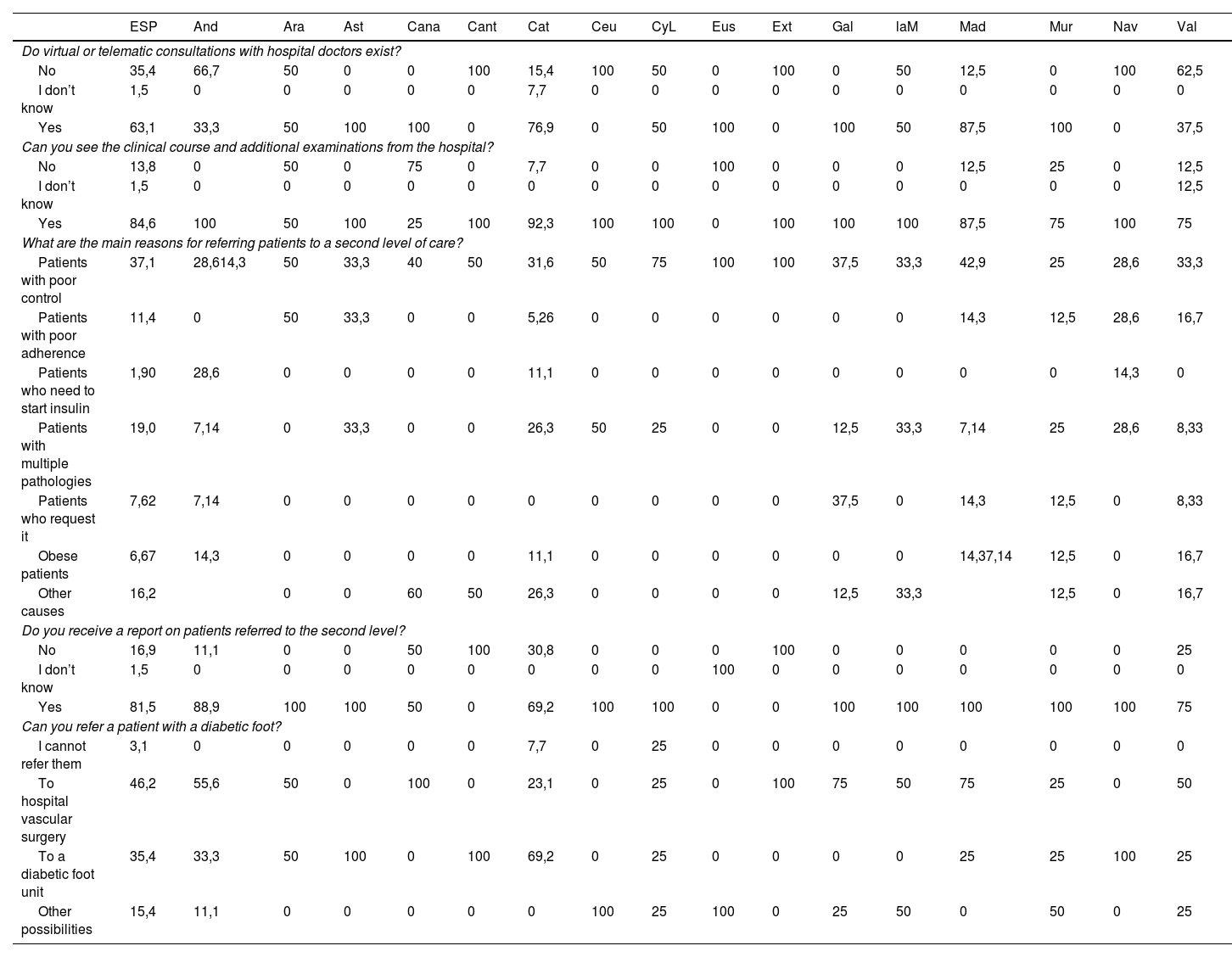

There is notable variability across autonomous communities in this aspect (Table 4).

Table 4.Primary/hospital referrals.

ESP And Ara Ast Cana Cant Cat Ceu CyL Eus Ext Gal laM Mad Mur Nav Val Do virtual or telematic consultations with hospital doctors exist? No 35,4 66,7 50 0 0 100 15,4 100 50 0 100 0 50 12,5 0 100 62,5 I don’t know 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 7,7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Yes 63,1 33,3 50 100 100 0 76,9 0 50 100 0 100 50 87,5 100 0 37,5 Can you see the clinical course and additional examinations from the hospital? No 13,8 0 50 0 75 0 7,7 0 0 100 0 0 0 12,5 25 0 12,5 I don’t know 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 12,5 Yes 84,6 100 50 100 25 100 92,3 100 100 0 100 100 100 87,5 75 100 75 What are the main reasons for referring patients to a second level of care? Patients with poor control 37,1 28,614,3 50 33,3 40 50 31,6 50 75 100 100 37,5 33,3 42,9 25 28,6 33,3 Patients with poor adherence 11,4 0 50 33,3 0 0 5,26 0 0 0 0 0 0 14,3 12,5 28,6 16,7 Patients who need to start insulin 1,90 28,6 0 0 0 0 11,1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14,3 0 Patients with multiple pathologies 19,0 7,14 0 33,3 0 0 26,3 50 25 0 0 12,5 33,3 7,14 25 28,6 8,33 Patients who request it 7,62 7,14 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 37,5 0 14,3 12,5 0 8,33 Obese patients 6,67 14,3 0 0 0 0 11,1 0 0 0 0 0 0 14,37,14 12,5 0 16,7 Other causes 16,2 0 0 60 50 26,3 0 0 0 0 12,5 33,3 12,5 0 16,7 Do you receive a report on patients referred to the second level? No 16,9 11,1 0 0 50 100 30,8 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 25 I don’t know 1,5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Yes 81,5 88,9 100 100 50 0 69,2 100 100 0 0 100 100 100 100 100 75 Can you refer a patient with a diabetic foot? I cannot refer them 3,1 0 0 0 0 0 7,7 0 25 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 To hospital vascular surgery 46,2 55,6 50 0 100 0 23,1 0 25 0 100 75 50 75 25 0 50 To a diabetic foot unit 35,4 33,3 50 100 0 100 69,2 0 25 0 0 0 0 25 25 100 25 Other possibilities 15,4 11,1 0 0 0 0 0 100 25 100 0 25 50 0 50 0 25 All values express percentages of the total in the column.

And: Andalusia; Ara: Aragon; Ast: Asturias; Cana: Canary Islands; Cant: Cantabria; Cat: Catalonia; Ceu: Ceuta; CyL: Castile and León; CS: health center; DM: diabetes mellitus; Eus: Basque Country; Ext: Extremadura; Gal: Galicia; laM: La Mancha; Mad: Madrid; Mur: Murcia; Nav: Navarre; Val: Valencian Community.

- o

Regarding lab test results, the most common practice is to request a control HbA1c every 6 mo (67.7%), although 20% adjust the frequency based on the patient.

- o

Significant differences are observed between autonomous communities (Table 3).

- o

- o

A total of 63.1% of PCCs can conduct teleconsultations with hospital specialists, and 84.6% have access to hospital health records and complementary examinations. A total of 81.5% receive follow-up reports for patients referred to secondary care.

- o

3.1% of PCCs report being unable to refer patients in a minimally operational manner.

- o

There is also significant variability between autonomous communities in this section (Table 4).

- o

Our study provides a detailed snapshot of the organization of diabetes care in PC across Spain, shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic, which strained the health care system in 2020–2021. After analyzing all surveys, notable heterogeneity is observed in almost all indicators across autonomous communities, reflecting the peculiarities of the Spanish health care system.

One strength of this study is its national representativeness, covering all autonomous communities. However, of note, the limitation of the small number of PCCs analyzed in some regions. Additionally, within each autonomous community, there may be significant differences between health care areas and even between PC managements.

For the care and management of people with diabetes, it is essential to have a solid organizational structure and well-defined goals, as well as the necessary resources to address this challenge. The National Diabetes Strategy recommends promoting the implementation of specific protocols for diabetes treatment and follow-up.7 Approximately 60% of PCCs have these protocols, although only half have a primary care professional designated as a diabetes reference.

Currently, most PC professionals (96.9%) have access to lists of T2DM patients assigned to their roster, allowing them to select patients based on other conditions or variables. The ability to actively contact and schedule appointments for patients without waiting for them to request an appointment can help reverse the Inverse Care Law, which states that “the availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served”.9

Regarding therapeutic education in diabetes, much of which is provided by the nursing staff (89.2%), it is considered a fundamental part of diabetes treatment. This education empowers patients to manage their condition, providing them with the knowledge and attitudes necessary to adhere to pharmacological treatment and adopt healthy lifestyles. These interventions have been shown to significantly improve glycemic control10 and reduce the development of T2DM.11,12

In general, it is considered that the treatment and follow-up of T2DM can be adequately managed in PC in most cases, provided that the necessary resources are available. A randomized study in Denmark in 2001 showed that T2DM management in PC reduced risk factors for complications.13 Additionally, other studies have shown that structured and shared management of the disease improves psychosocial outcomes14 and clinical results, such as reduced cardiovascular events and mortality.15,16

For effective T2DM management, it is essential to establish clear and agreed-upon action algorithms and referral protocols between care levels, based on the recommendations of the Ministry of Health CPG8 and adapted to the specific context of each region. According to survey data, a total of 63.1% of PCCs can conduct teleconsultations with specialized care, and 84.6% have access to hospital health records. Strengthening this coordination between care levels is crucial for patient benefit and resource optimization.

Regarding the availability of examinations and laboratory tests, HbA1c testing is available in all PCCs and is requested every 6 mo in 67.7% of cases, although 20% adjust the frequency based on patient characteristics. Unfortunately, 20% of PCCs have limited access to certain laboratory tests necessary for proper disease control, with significant variability across autonomous communities.

The prevention and early detection of micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes are key tasks in PC. Diabetic retinopathy, one of the leading causes of blindness worldwide,17,18 is recommended to be screened through non-mydriatic retinography every 2 years. Only 38.5% of surveyed centers perform this test, a figure possibly due to its centralization in specific centers within each health care region.19 Approximately 23% of retinographies are interpreted by ophthalmologists.

The combination of ischemia and neuropathy can lead to ulcers and diabetic foot, with risks of infection and amputations.20 Screening for this complication is recommended annually,5 and according to our survey, it is primarily performed by the nursing staff. However, 3.1% of centers do not regularly examine the feet of people with diabetes. Some autonomous communities, such as Andalusia, Catalonia, and Castile-La Mancha, can complement diabetic foot care and prevention by referring patients to podiatry through the Spanish National Health System.21 In case of complications, referral to diabetic foot units, composed of multidisciplinary teams (endocrinology, surgery, traumatology, infectious diseases, and expert nursing),22 occurs in 35.4% of centers, with a significant number referring to vascular surgery in the absence of a specific unit.

As limitations of this study, we highlight that the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, so the data might differ now due to the impact of the pandemic on PC. We are working on a new survey to analyze potential improvements.

In conclusion, T2DM care in Spain shows significant differences across autonomous communities, affecting organization, access to examinations, and referrals between care levels. To optimize T2DM management, it is essential to promote coordination between different care levels and ensure the availability of necessary resources.

ConclusionsThe first conclusion to draw from this study is the surprising heterogeneity observed in most aspects studied across autonomous communities, likely due to the organizational peculiarities of the Spanish health care system.

In general, it is considered that most T2DM patients can be adequately and comprehensively managed in PC. However, for optimal management of this condition, both in preventive aspects and when complications arise or poor control is achieved, good coordination with hospital specialists is essential. In Spain, there are generally good shared care systems for the management T2DM, although there is again significant heterogeneity across regions.

Further studies are needed to define potential improvements in organizational aspects of each autonomous community to optimize coordination between health care levels.

FundingNone declared.

Basterra Gortari, Francisco Javier (University Hospital of Navarra, Pamplona); Castaño González, Luis (Cruces Hospital, Bilbao); Castell Abat, Conxa (Diabetes Advisory Council, Barcelona); Conde Barreiro, Santiago (Barbastro PCC, Huesca); de Pablos Velasco, Pedro (Dr. Negrín Hospital Complex, Las Palmas); Delgado Álvarez, Elías (Central Hospital of Asturias, Asturias); Ena Muñoz, Javier (Villajoyosa Hospital, Alicante); Franch Nadal, Josep (Raval Sud PCC, Barcelona); Goday Arno, Albert (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); Menéndez Torre, Edelmiro (Central Hospital of Asturias, Asturias); Ortega Martínez, Emilio (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); Rojo Martínez, Gemma (Carlos Haya University Hospital, Málaga); Salinero Fort, Miguel Ángel (Ministry of Health, Madrid); Sangrós González, Francisco Javier (Torrero La Paz PCC, Zaragoza); Santos Mata, María Ángeles (SAS Hospital of Jerez, Cádiz); and Simó Canonge, Rafael (Vall d’Hebron Hospital, Barcelona).