Herpes zoster is caused by a reactivation of the varicella zoster virus. Clinically, the disease manifests with pain in the area of a dermatome associated with vesicular exanthema. The most common complication is post-herpetic neuralgia, more frequent among elderly patients. The treatment focuses on the control of the acute infection, relief of acute pain, and prevention of chronic pain. First line treatment is pharmacological using antiviral and analgesic drugs, and epidural injections have been used for the prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia.

ObjectiveThe objective of this article is to present a review of the literature on the basis of a case report of a patient diagnosed with herpes zoster who was treated with cervical epidural infusions for 16 days.

Materials and methodsSearch conducted in PUBMED, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews, clinical trials, narrative reviews and case series published between 1995 and 2012, in order to perform a non-systematic narrative review in reference to a case report.

ResultsOverall, 31 articles were selected for an update of the topic proposed, and a case report was described.

ConclusionsThe use of epidural infusions in patients with herpes zoster is a treatment option for acute pain; it favors passive motion of the affected limb preventing atrophy, helps prevent post-herpetic neuralgia, is available in our setting, and has a low incidence of complications.

El herpes zoster es causado por una reactivación del virus de la varicela zoster. Clínicamente la enfermedad se manifiesta con dolor en la zona de un dermatoma asociado a un exantema vesicular. La complicación más común es la neuralgia pos herpética, más frecuente en el adulto mayor. El tratamiento está enfocado al control de la infección aguda, al alivio del dolor agudo y a la prevención del dolor crónico. El tratamiento de primera línea es farmacológico, con antivirales y analgésicos; las inyecciones epidurales han sido usadas con el fin de prevenir la neuralgia pos herpética.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del presente artículo es presentar una revisión de la literatura aprovechando el reporte de un caso de un paciente con diagnóstico de herpes zoster que fue tratado con infusiones epidurales cervicales por 16 días.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda en la base de datos PUBMED, que incluyó artículos de metaanálisis, revisiones sistemáticas, ensayos clínicos, revisiones narrativas y series de casos, entre 1995 y 2012, para la realización de una revisión narrativa no sistemática y reporte de un caso.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 31 artículos para la realización de la actualización en el tema propuesto y se describió el reporte del caso.

ConclusionesEl uso de infusiones epidurales en pacientes con herpes zoster es una alternativa en el tratamiento del dolor agudo: favorecen una movilización pasiva de la extremidad afectada evitando la atrofia de esta, ayudan a prevenir la neuralgia pos herpética, están disponibles en nuestro medio y tienen una baja incidencia de complicaciones.

Herpes zoster (HZ) is caused by the reactivation of the varicella zoster virus in neurons of the dorsal root ganglion. Clinically, the disease manifests in the form of unilateral pain in a dermatome area, associated with vesicular skin exanthema. Pain occurring after resolution of an acute HZ infection may be severe and, therefore, the most common complication associated with this disease in immunocompetent patients is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) due to nerve damage caused by HZ.1 PHN is defined as the persistence of pain for more than 90 days after the onset of the herpetic rash2; the incidence has been found to range from 10% in people of all ages with HZ, up to 40% in people over 50, supporting the fact that age is the main risk factor.3 Other risk factors associated with PHN include severe pain during HZ, more severe skin exanthema, greater nerve compromise in the affected dermatome, more severe immune response, and psychological and social factors.4

Although multiple forms of prevention and treatment have been proposed for PHN,5 over the years new techniques have been suggested for pain relief using interventional procedures like the one proposed in this case report, namely, epidural infusions.

Materials and methodsA non-systematic narrative review was conducted on the basis of a literature search in the PUBMED database, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews, clinical trials, narrative reviews, and case series published between 1995 and 2012. The terms used for the search [MeSH] were: “herpes zoster”, “postherpetic neuralgia”, “spinal Injections”, “glucocorticoids” and chronic pain. Only articles published in English or Spanish were evaluated.

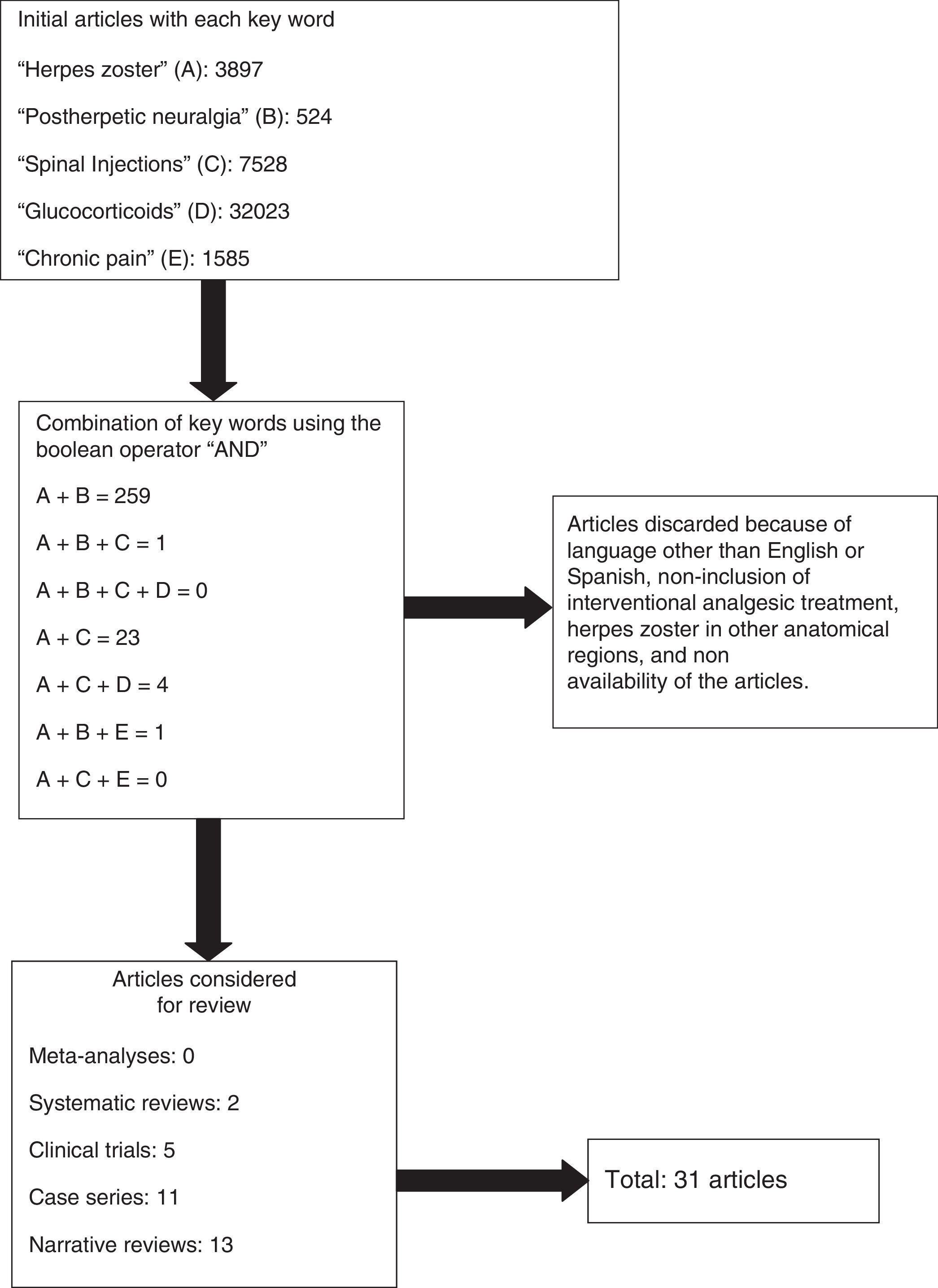

ResultsA total of 45,557 articles were obtained. No results were obtained with the combination of the five key words. Combinations between the key words resulted in 259 articles, of which 31 were taken into account. The rest were discarded because of language other than English or Spanish, non-inclusion of interventional analgesic treatment, herpes zoster in other anatomical sites, and non-availability of the articles (Fig. 1).

Case descriptionSeventy-six-year-old male patient who came to a Level IV hospital in Medellin with a diagnosis of HZ in the left upper limb, allodynia and burning pain rated as 10/10 on the visual analog scale (VAS). The patient was treated initially with acyclovir 3200mg/day for three days, oral oxycodone 10mg every 12h, and oral pregabalin 75mg every night, with little improvement of pain. The patient developed severe cognitive dysfunction associated with the drug therapy. The treating physician interrupted oxycodone and pregabalin and started 5% lidocaine patches on the area of the skin affected by the vesicular lesions. A severe erythematous response required interrupting the use of the patch. Later, the patient was given oral amitriptyline 25mg before bedtime plus tramadol drops every 6h, with no pain improvement. The patient developed severe constipation that required hospital treatment consisting of two enemas and manual disimpaction. Given symptom severity, poor response to treatment and multiple adverse effects, the patient was referred to the Colombian Pain Institute where he was admitted on day 26 after the onset of skin vesicles, with intense pain (10/10), allodynia of the left upper limb, especially in the territory of C5 and C6, muscle strength of 3/5 in the muscles innervated by the superior trunk of the left brachial plexus, hypoesthesia of the left thumb and normal healing process of the skin in the arm; additionally, the patient was downcast, asthenic, unresponsive, and reported insomnia and disturbed sleep as a result of the pain. Important disease history included diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, blood hypertension and coronary heart disease with bypass surgery.

The inter-disciplinary team decided to perform the following interventional management, after obtaining informed consent that included an explanation of all the risks reported for the intervention:

- 1.

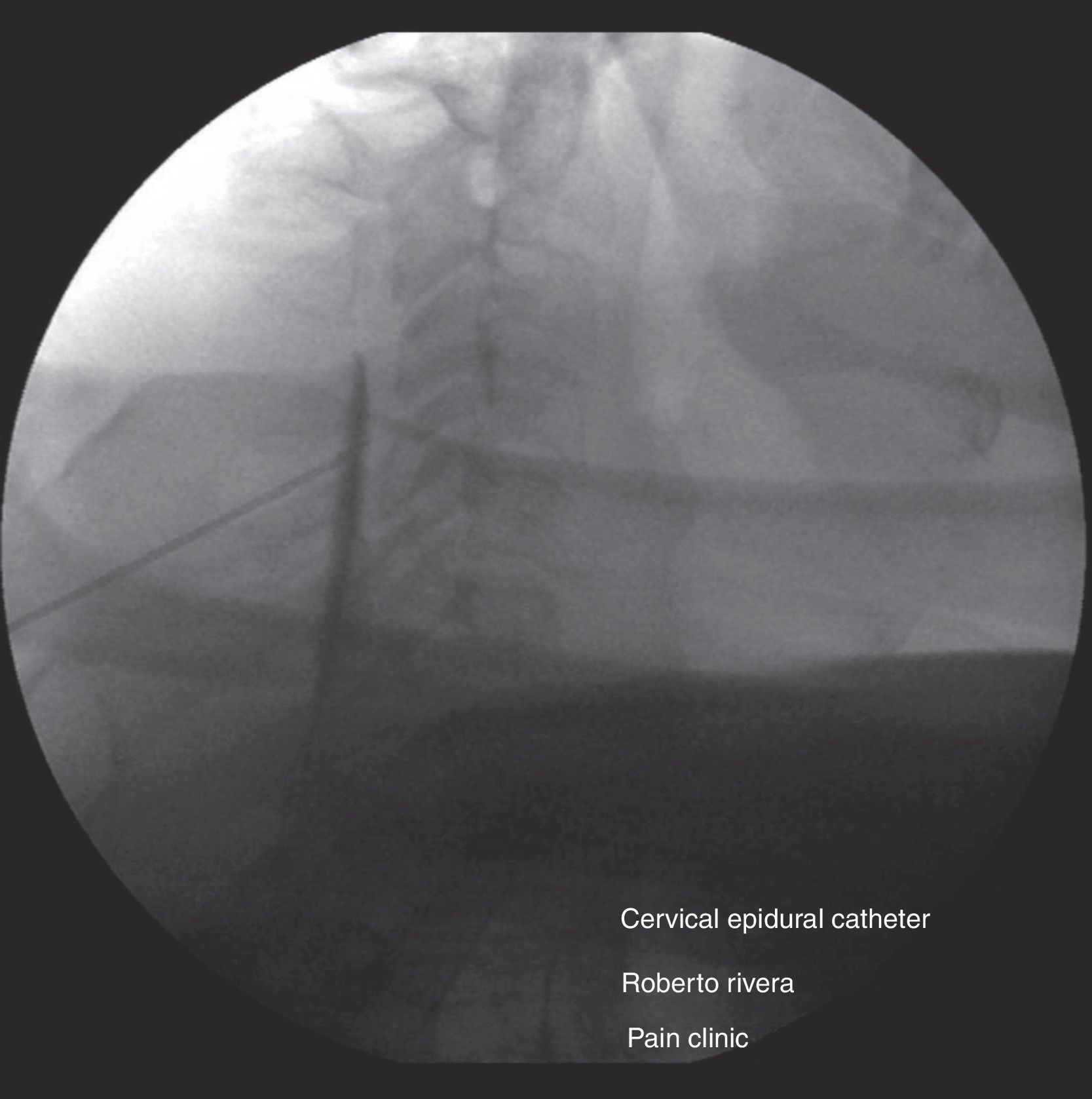

Epidural steroids under basic monitoring, intravenous sedation and local anesthesia, and fluoroscopic guidance. The patient was placed in prone decubitus and the epidural space at the level of C4/C5 was located (Fig. 2) using the epidural needle and the loss-of-resistance technique with saline solution. It was confirmed with 0.5mL of contrast medium (omnipaque 300mg/mL), followed by 40mg of methylpredinisolone acetate+1mL of 0.75% levobupivacaine+2mL of 0.9% saline solution (0.9% SS) (Fig. 3).

- 2.

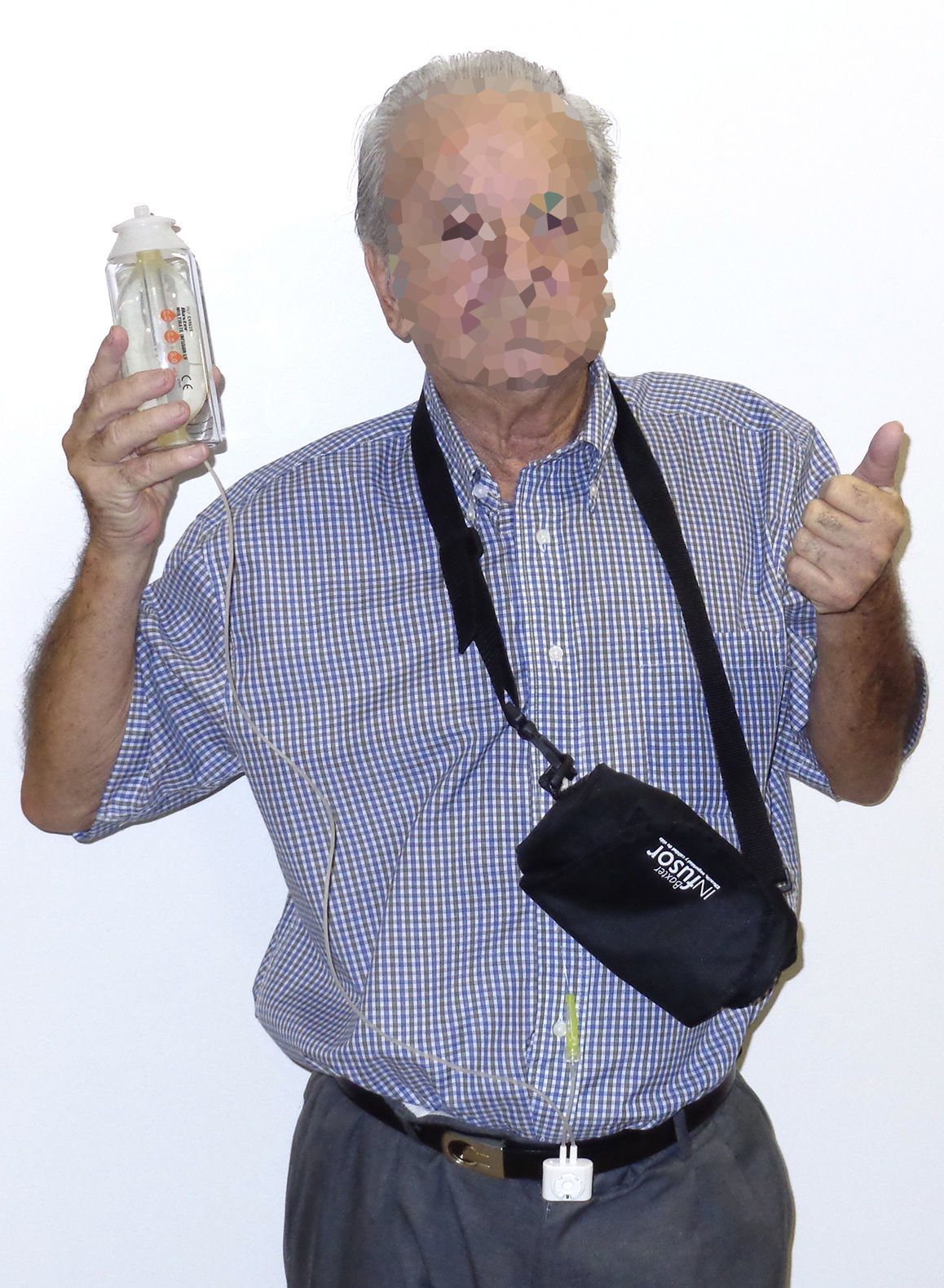

Continuous epidural analgesia: after steroid application, an epidural catheter was inserted 5cm inside the epidural space with tunneling, followed by a test using 3mL of 1% lidocaine plus 15μg of epinephrine to rule out intrathecal or intravascular catheter placement (Fig. 4). Continuous infusion was then started using an elastomeric pump with 250mL of 0.9% SS+50mL of 0.75% levobupivacaine; the pump offered the possibility of using three different fixed infusions – 3, 4 and 6mL/h. The infusion rate selected was 2mL/h. One day later, pain was rated as 5/10 on the VAS. The infusion rate was increased to 4mL/h and 6mL/h during crisis periods. During two days of the infusion period, 300μg of clonidine were added to the preparation for delivery at a rate of 6μg/h, and 500mg of ketamine were added during the last two days for delivery at a rate of 10mg/h. The patient continued to receive the epidural infusion for a total of 16 days on an outpatient basis, with follow-up visits to the clinic every two days and pump refill; during this time, pain remained under control (0–3/10 on the VAS), with a few breakthrough episodes of 6/10 lasting less than 30min. There were no instances of motor block or adverse events associated with the epidural infusion, and the patient was even able to start physical rehabilitation of his limb. Quality of sleep improved and there was no need for additional medication through a different route (Fig. 5). The catheter was removed on day 16 with no complications and the treatment continued with half a tablet of hydrocodone 5mg plus acetaminophen 500mg four times a day orally for another 15 days. At present, the patient dos not require analgesic treatment; he recovered limb strength and limb atrophy improved with the early physical therapy.

Varicella zoster virus infection gives rise to two types of diseases: varicella, which is found most frequently in children and where the main symptom is pruritus; and HZ in the adult population, where pain is the main manifestation and sequela. On histopathology, the skin shows loss of sensory fibers, suggesting a relationship between the amount of axonal damage and the development of the disease. Multi-segment dorsal horn atrophy and the presence of subclinical changes in contralateral skin innervation have been described.6 There is a direct relationship between the incidence of HZ in the general population and age. It is infrequent among people under 50 years of age, contrary to what happens in those over 80, in whom the incidence is 10 cases for every 1000 healthy patients.5 The most important risk factor in the patient described here was age (76), increasing also the risk of postherpetic neuralgia. The incidence of PHN in patients over 70 years of age ranges between 30% and 50%, requiring optimal treatment during the acute phase of the disease.7 PHN still persists in more than 2% of patients with HZ after five years.1

HZ has a significant effect on quality of life. A prospective study of 261 patients over 50 with a diagnosis of HZ of more than 15 days of duration and six months of follow-up reported sleep disorders in 64%, reduced ability to enjoy life in 58%, and general activity limitations in 53%.2 Other studies report that patients with PHN suffer more from chronic fatigue, weight loss, anorexia and major depression.8,9

The initial pharmacological treatment in this patient with HZ was acyclovir 3200mg/day for three days, oxycodone and pregabalin. For antiviral treatment, the use of valacyclovir 1000mg every 8h for 7–14 days was shown to be more effective than acyclovir 800mg five times a day for seven days in terms of acute and chronic pain reduction. Similar results have been found with famcyclovir 500mg every 8h for 7 days. Antivirals must be initiated within the first 72h of skin rash onset.2,10 Regarding the management of acute pain during HZ, no drug has been show to be superior to another. For the prevention of chronic pain, dual antidepressants such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, and other drugs such as gabapentin, oral opioids and dextrometorphan, capsaicine, topical antivirals and oral steroids during the acute face, have not been shown to lower the incidence of PHN; however, their use is warranted for the prevention of central sensitization. The use of lidocaine patches on the skin affected by the acute rash is contraindicated.11

In elderly patients, changes in drug metabolism, protein binding, distribution and clearance may result in increase opioid adverse effects, including cognitive disorders.12

Tricyclic antidepressants have been used in patients with HZ in order to prevent PHN or for the management of this complication when it occurs; studies have reported benefit in both situations.13,14 However, the use of tricyclic antidepressants is not recommended in patients over 65 or with a history of heart disease, because of the risk of triggering fatal arrhythmias. Consequently, amitriptyline was not an appropriate option in this patient.15

Conventional treatment does not provide adequate control of pain in 50% of patients,2 which is why interventional management with analgesic blocks must be considered. A systematic review reported grade A evidence for epidural steroids during the acute phase of HZ.16 The steroid used in this case was methylprednisolone acetate containing 40mg of methylprednisolone acetate, polyethylene glycol 3350, sodium chloride and miripirium chloride.

A cost-effectiveness study on the use of epidural steroids in patients over 50 years of age with HZ for the prevention of PHN showed that symptom reduction in patients receiving a single injection of steroids plus local anesthetic was the same as in the control group.17 In this report, continuous infusion, unlike single injection, may impact the course of the disease.

The use of epidural steroids provides a higher concentration of the drug in the dorsal root ganglion involved, allowing the use of lower doses. However, it may lead to an increase in blood sugar, particularly during the first two weeks; this is not a contraindication for patients with diabetes, but requires closer monitoring of plasma levels and adjustment of the drug therapy with insulin, depending on the case.18,19 When slow-release epidural steroids are used, as was the case in this report, the literature reports no difference in pain improvement with a 40mg dose compared with 80mg of depomedrol, while the 80mg dose does increase blood sugar values, a situation that is relevant particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus.20

The percentage of failure of cervical epidural injections, when performed blindly, is up to 53%, hence the recommendation for using fluoroscopic or tomographic guidance.21–23

Multiple reports have been published on the use of continuous infusions with different drug mixes including ketamine and clonidine, with satisfactory results. Elkersh et al. reported the case of a 73 year-old female with melanoma and brain metastasis, affected by HZ in the territory of the left ophthalmic root of the trigeminal nerve, pain, and severe pruritus. The patient was treated with a continuous infusion of bupivacaine plus clonidine 5μ/h for two weeks given through a thoracic epidural catheter, with almost total symptom resolution.24 Kishimoto et al. reported one case in which they used continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetic. Like in this case, they added ketamine to the treatment, with resolution of neuropathic symptoms, mainly allodynia.25

Later on, the same group published four cases of patients with HZ who received 5–10mg of ketamine plus local anesthetic through continuous epidural infusion, with excellent results.26 A randomized double-blind clinical trial with 56 immunocompetent patients comparing continuous epidural infusion of 0.5% bupivacaine versus placebo (saline solution) showed pain improvement at 29 days, compared with 40 days for the control group. In 10% of the patients in the treatment group allodynia persisted after 30 days, compared with con 37% in the control group.27

Epidural infusions given over several days have been challenged because of the risk of infection, urinary retention and motor block. However, there are multiple series in which this technique has been used over long periods of time (between 15 and 30 days) with a low incidence of infectious events. Moreover, when the epidural catheter is placed at the ideal metameric level, a sensory blockade may be achieved with a low infusion volume. Also, motor block and urinary retention are avoided with the use of local anesthetics at analgesic concentrations.28

Another frequent complication of HZ, when it affects a limb, is atrophy and diminished strength of the muscles of the involved myotome. This event is more frequent in the population over 60 years of age and is observed starting in the acute phase. In many instances, physical rehabilitation may be difficult due to pain associated with movement and, therefore, epidural analgesia may help with this process.29

HZ continues to be a prevalent disease in pain clinics, hence the importance of emphasizing vaccination in patients over 60 years of age. Primary prevention, vaccination in particular, is the most effective strategy to reduce the incidence and severity of HZ disease, as well as to prevent PHN in elderly patients, according to the Shingles Prevention Study.30 The vaccine reduces HZ development by 50% and PHN by 67% in people over 60 years of age. Although it is safe, it is underutilized because of cost considerations. In Canada, only 7% of the population that could be vaccinated was actually immunized in 2008.3

The vaccine available at the present time is Zoster Vaccine Live. It contains attenuated varicella zoster virus and is designed for subcutaneous application in the deltoid region of the arm; it must be stored at a temperature of −15°C (5°F). It may be administered together with other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, but it cannot be given together with the pneumococcus vaccine because it diminishes the immune response. This vaccine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of HZ disease in individuals 60 years and older. In the United States, the cost of the vaccine ranges between 150 and 172 dollars.31 In Colombia, it was approved by INVIMA in 2008 for use in patients over 50 years of age.

ConclusionsHZ and subsequent PHN continue to be common diseases among individuals over 60 years of age. The little use of immunization with the existing vaccines limits primary prevention. Anti-viral therapy and adequate pain control during the acute phase are critical for preventing chronic pain. The use of epidural infusions at the level of the involved dermatome is an adequate option for pain control during the acute phase and for the delivery of drugs such as steroids, ketamine, clonidine and local anesthetics that help prevent the onset of PHN. It is important to consider the use of fluoroscopic guidance to ensure adequate catheter placement in the right epidural space and level. Moreover, epidural analgesia provides for painless physical rehabilitation, avoiding atrophy of the limb involved which is a frequent complication of this disease.

FundingThis review was funded with personal resources, with the advice from Universidad CES.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare having no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rivera Díaz RC and Arcila Lotero MA. Infusión epidural cervical para tratamiento del dolor por herpes zoster. Reporte de caso con revisión temática. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013;41:291–297.