Sclerosing stromal tumors (SSTs) are rare benign ovarian tumors. They represent 6% of sex cord stromal tumors. Its preoperative diagnosis is often a challenge due to its similarity to malignant tumors on ultrasound imaging. We present two cases of SSTs to emphasize the consideration of this type of tumors in the differential diagnosis of solid adnexal masses in young women. A review of the literature on the typical ultrasound features, clinical presentation, and management of SSTs was performed.

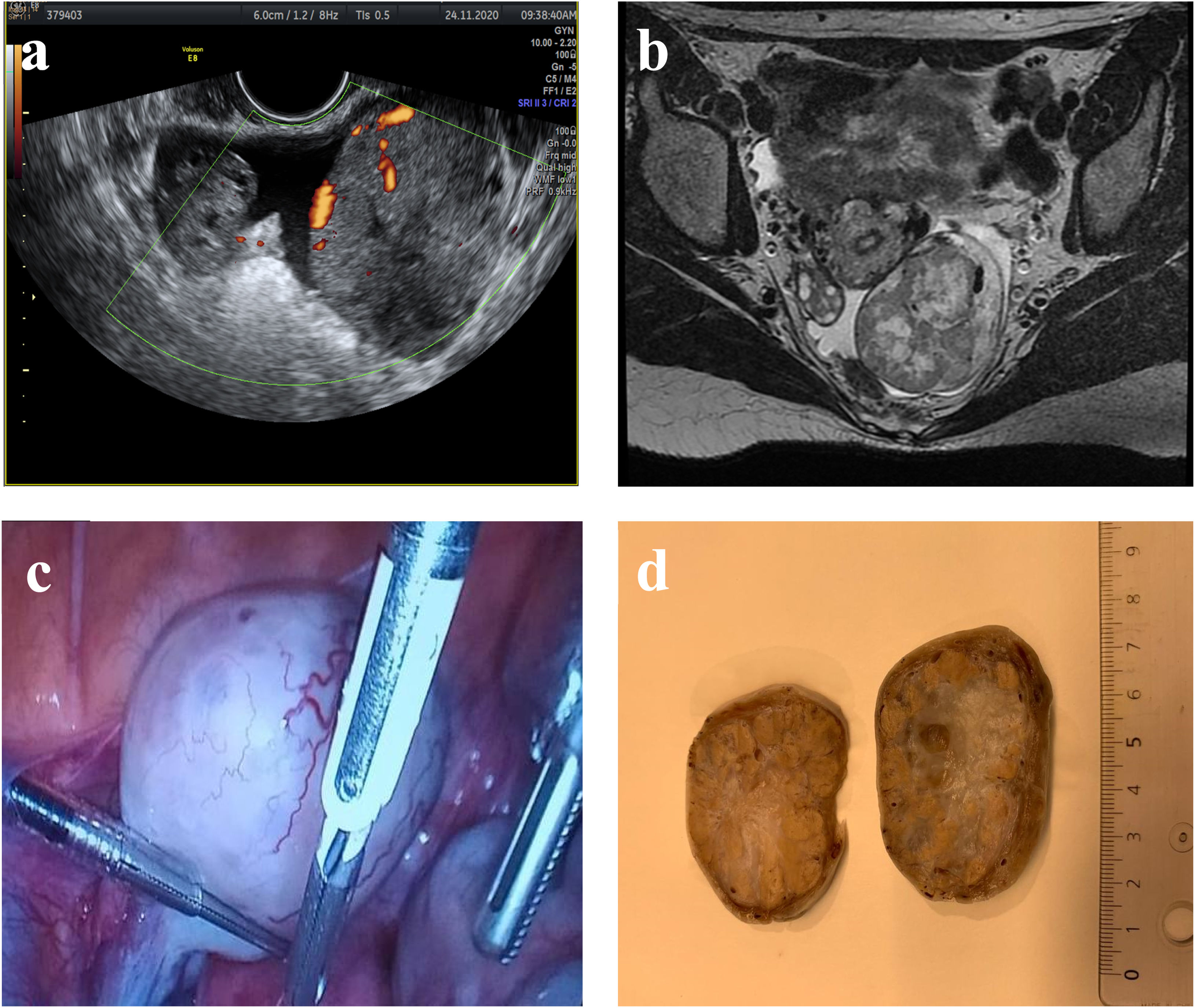

Main symptoms and/or clinical findingsPelvic pain was the main symptom in both cases. In the first case, transvaginal ultrasound revealed an unilocular solid adnexal mass of 59mm×44mm×45mm with cystic areas and marked peripheral and central vascularization. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) revealed a 50mm×50mm heterogeneous adnexal mass with a solid peripheral component and a cystic-necrotic center. In the second case, pelvic ultrasound showed a solid cystic adnexal mass of 103mm×77mm with marked peripheral vascularity.

Main diagnosesPostoperative anatomopathological diagnosis in both cases was an ovarian SST.

Therapeutic interventions and resultsUnilateral laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and oophorectomy, respectively, was performed without incidents. There has been no recurrence during follow-up.

ConclusionIt is important to consider SSTs in the differential diagnosis of young women with a unilateral solid-cystic adnexal mass with a high degree of peripheral and central vascularization. Laparoscopic approach together with fertility-sparing techniques should be considered the treatment of choice.

Los tumores esclerosantes del estroma (SST) son tumores benignos raros del ovario. Representan un 6% de los tumores del estroma de los cordones sexuales. Su diagnóstico preoperatorio suele ser un desafío por su similitud ecográfica con los tumores malignos. Presentamos 2 casos de SST para enfatizar la consideración de este tipo de tumores en el diagnóstico diferencial de masas anexiales sólidas en mujeres jóvenes. Se realizó una revisión de la literatura sobre las características ecográficas típicas, la presentación clínica y el manejo de los SST.

Principales síntomas y/o hallazgos clínicosEl dolor pélvico fue el síntoma principal en ambos casos. En el primer caso, la ecografía transvaginal reveló una masa anexial unilocular sólida de 59×44×45mm con áreas quísticas y marcada vascularización periférica y central. La resonancia magnética nuclear reveló una masa anexial heterogénea de 50×50mm con componente sólido periférico y un centro quístico-necrótico. En el segundo caso, la ecografía pélvica mostró una masa anexial sólido quística de 103×77mm con marcada vascularización periférica.

Diagnósticos principalesEl diagnóstico anatomopatológico postoperatorio en ambos casos fue de un SST de ovario.

Intervenciones terapéuticas y resultadosSe realizó ooforectomía y salpingooforectomía unilateral laparoscópica, respectivamente, sin incidencias. No se ha producido recidiva durante el seguimiento.

ConclusiónEs importante considerar los SST en el diagnóstico diferencial ante mujeres jóvenes con una masa anexial sólido-quística unilateral con un alto grado de vascularización periférica y central. El abordaje laparoscópico junto con técnicas preservadoras de fertilidad deben ser consideradas el tratamiento de elección.

Sclerosing stromal tumors (SST) of the ovary are a rare benign neoplasm that account for approximately 8% of all primary ovarian neoplasms.1 They are a subtype of ovarian stromal neoplasms of the sex chord-stromal category. This entity was first reported in 1973 by Chalvardjan and Scully.2 Unfortunately, lack of familiarity with this entity makes a preoperative diagnosis challenging.

They usually appear in young women and common clinical presentations of SST include menstrual irregularities, pelvic pain, or nonspecific symptoms associated with pelvic mass.3 Imaging findings for SSTs can mimic those of borderline or malignant ovarian tumors. Transvaginal ultrasound is usually the first step. Gray-scale ultrasound 4 and color Doppler findings have been described in previous publications.5,6

To contribute to the proper clinical, ultrasound and pathological evaluation of SST and highlight the importance of considering SST in the differential diagnosis in young women, we describe two cases of SST.

Patient informationIn our first case, a 21-year-old healthy nulliparous woman without medical or surgical history of concern, was presented in the outpatient department of gynecology with pelvic pain during the last 3 months.

In the second case, a 19-year-old caucasian woman without medical or surgical history of interest presented to the emergency department with sudden onset of abdominal pain. A urine pregnancy test was negative. The patient had been diagnosed of an ovarian mass a few months ago and was being followed up in an outpatient clinic and waiting for surgery.

Clinical findingsIn the first case, a vaginal examination revealed a large, palpable mass in the pouch of Douglas. There were no unusual symptoms such as hypermenorrhea, menstrual irregularities or virilization. In the second case, on abdominal palpation, a firm mass in the hypogastric region was noted.

Timeline and diagnostic assessmentIn the first patient, ultrasound examination showed a normal uterus and right ovary (Fig. 1a). On the left site there was an unilocular solid mass of 59mm×44mm×45mm with cystic areas and peripheral and central vascularization with doppler score 3. Minim free fluid in the pouch of Douglas was found. Ultrasound evaluation of the mass was GIRADS-4 with suspicion of a non-epithelial tumor. Laboratory tests, including tumor markers (Ca-125, Ca-19.9, alpha-FP), were normal. MRI was performed and revealed a heterogeneous left adnexal mass of 5cm×5cm with peripheral solid component and a cystic-necrotic center showing a low signal on T1 and heterogeneous on T2, with enhancement of solid component. The right ovary, uterus and cervix were without alterations (Fig. 1b).

(a) Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a solid hypoechoic tumor with cystic areas and regular borders with multiple vessels in the periphery and central part. The right ovary was normal. A small amount of free fluid was present. (b) MRI revealed an ovoid solid tumor with regular contours. (c) On laparoscopy a solid lobulated mass with a high vascularized capsule depending of the left ovary was found. (d) Macroscopic examination revealed a capsulated tumor with firm consistency and yellowish nodular peripheral components and an oedematous central part.

In the second case, pelvic ultrasonography showed a right solid-cystic adenxal mass of 103mm×77mm with marked peripheral vascularization. The left ovary and uterus were normal.

Therapeutic interventionThe first patient underwent laparoscopic surgery with left oophorectomy as there was no normal ovarian tissue present. Surgery revealed a normal uterus and right ovary with the left ovary replaced by a solid mass with marked superficial vascularization (Fig. 1c). On gross inspection, the removed left ovarian mass measured 64mm×55mm×40mm. The mass was gray-white in color and had a smooth and well-encapsulated surface with prominent vascularization. The cut surface was a mostly solid with a medium-elastic consistency and slightly edematous in the center with a peripheral multinodular orange border (Fig. 1d).

The second patient also underwent laparoscopy, which revealed the presence of a large solid adnexal mass which was torsioned. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was conducted.

The histological diagnosis in both cases was a SST of the ovary.

Follow-up and outcomesThe first patient's postoperative course was uneventful. She was discharged on day 2 after surgery. No recurrence has occurred during 11 months of follow-up. In the second case, post-operative recovery was uneventful, and no recurrence has occurred during follow-up.

DiscussionSST are a rare benign ovarian neoplasm that account for approximately 8% of all primary ovarian neoplasms. They are attributable to theca cell-fibrous tumor subtypes of ovarian sex cord-stromal tumor and account for approximately 6% of them.3

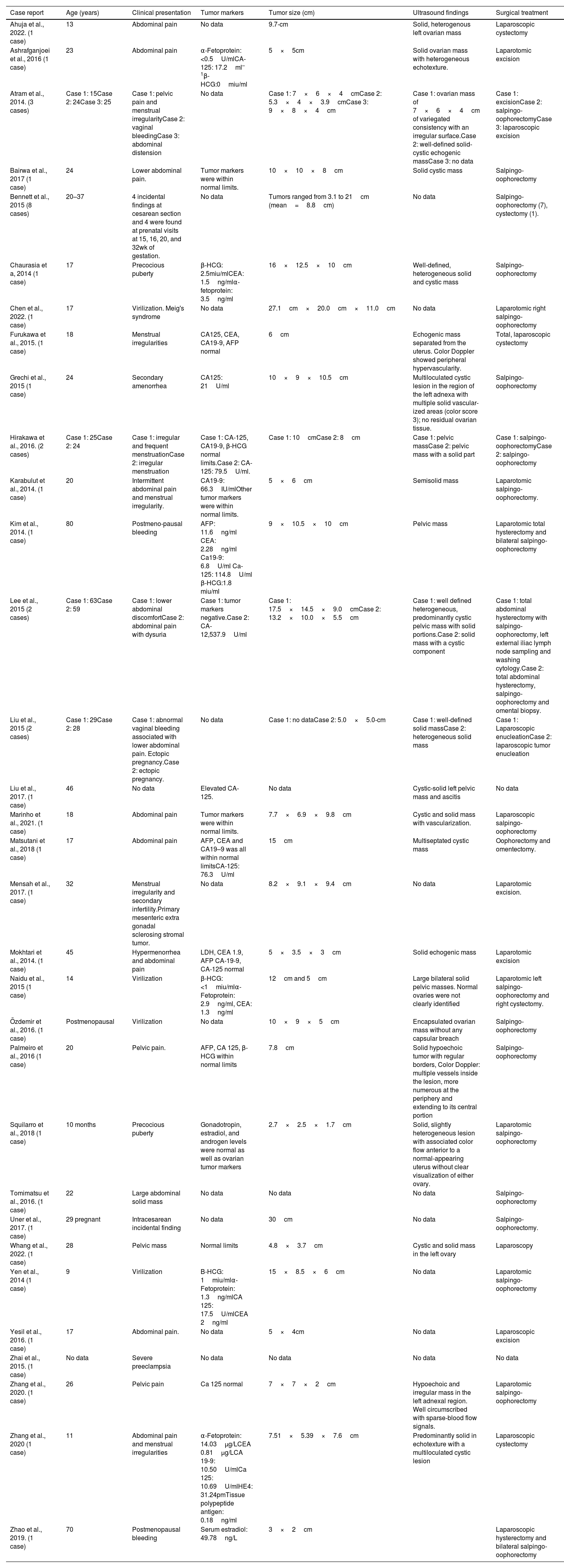

In the literature, reports of ovarian SSTs are rare. Until 2003, 114 cases have been reported by Peng et al.3 Ozdemir et al.7 reported a total of 208 cases until 2014. We undertook a MEDLINE® search using keywords “ovarian neoplasms” and “sclerosing stromal tumor” to obtain case reports on this tumor in the English literature. A total of 44 cases from 32 reports have been identified from 2014 up to the writing of this paper in 2022. The clinical reports and their characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Overview of case reports on SST between 2014 and 2022.

| Case report | Age (years) | Clinical presentation | Tumor markers | Tumor size (cm) | Ultrasound findings | Surgical treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahuja et al., 2022. (1 case) | 13 | Abdominal pain | No data | 9.7-cm | Solid, heterogenous left ovarian mass | Laparoscopic cystectomy |

| Ashrafganjoei et al., 2016 (1 case) | 23 | Abdominal pain | α-Fetoprotein: <0.5U/mlCA-125: 17.2ml–1β-HCG:0miu/ml | 5×5cm | Solid ovarian mass with heterogeneous echotexture. | Laparotomic excision |

| Atram et al., 2014. (3 cases) | Case 1: 15Case 2: 24Case 3: 25 | Case 1: pelvic pain and menstrual irregularityCase 2: vaginal bleedingCase 3: abdominal distension | No data | Case 1: 7×6×4cmCase 2: 5.3×4×3.9cmCase 3: 9×8×4cm | Case 1: ovarian mass of 7×6×4cm of variegated consistency with an irregular surface.Case 2: well-defined solid-cystic echogenic massCase 3: no data | Case 1: excisionCase 2: salpingo-oophorectomyCase 3: laparoscopic excision |

| Bairwa et al., 2017 (1 case) | 24 | Lower abdominal pain. | Tumor markers were within normal limits. | 10×10×8cm | Solid cystic mass | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Bennett et al., 2015 (8 cases) | 20–37 | 4 incidental findings at cesarean section and 4 were found at prenatal visits at 15, 16, 20, and 32wk of gestation. | No data | Tumors ranged from 3.1 to 21cm (mean=8.8cm) | No data | Salpingo-oophorectomy (7), cystectomy (1). |

| Chaurasia et a, 2014 (1 case) | 17 | Precocious puberty | β-HCG: 2.5miu/mlCEA: 1.5ng/mlα-fetoprotein: 3.5ng/ml | 16×12.5×10cm | Well-defined, heterogeneous solid and cystic mass | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Chen et al., 2022. (1 case) | 17 | Virilization. Meig's syndrome | No data | 27.1cm×20.0cm×11.0cm | No data | Laparotomic right salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Furukawa et al., 2015. (1 case) | 18 | Menstrual irregularities | CA125, CEA, CA19-9, AFP normal | 6cm | Echogenic mass separated from the uterus. Color Doppler showed peripheral hypervascularity. | Total, laparoscopic cystectomy |

| Grechi et al., 2015 (1 case) | 24 | Secondary amenorrhea | CA125: 21U/ml | 10×9×10.5cm | Multiloculated cystic lesion in the region of the left adnexa with multiple solid vascular- ized areas (color score 3); no residual ovarian tissue. | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Hirakawa et al., 2016. (2 cases) | Case 1: 25Case 2: 24 | Case 1: irregular and frequent menstruationCase 2: irregular menstruation | Case 1: CA-125, CA19-9, β-HCG normal limits.Case 2: CA-125: 79.5U/ml. | Case 1: 10cmCase 2: 8cm | Case 1: pelvic massCase 2: pelvic mass with a solid part | Case 1: salpingo-oophorectomyCase 2: salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Karabulut et al., 2014. (1 case) | 20 | Intermittent abdominal pain and menstrual irregularity. | CA19-9: 66.3IU/mlOther tumor markers were within normal limits. | 5×6cm | Semisolid mass | Laparotomic salpingo- oophorectomy. |

| Kim et al., 2014. (1 case) | 80 | Postmeno-pausal bleeding | AFP: 11.6ng/ml CEA: 2.28ng/ml Ca19-9: 6.8U/ml Ca-125: 114.8U/ml β-HCG:1.8 miu/ml | 9×10.5×10cm | Pelvic mass | Laparotomic total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Lee et al., 2015 (2 cases) | Case 1: 63Case 2: 59 | Case 1: lower abdominal discomfortCase 2: abdominal pain with dysuria | Case 1: tumor markers negative.Case 2: CA-12,537.9U/ml | Case 1: 17.5×14.5×9.0cmCase 2: 13.2×10.0×5.5cm | Case 1: well defined heterogeneous, predominantly cystic pelvic mass with solid portions.Case 2: solid mass with a cystic component | Case 1: total abdominal hysterectomy with salpingo-oophorectomy, left external iliac lymph node sampling and washing cytology.Case 2: total abdominal hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy and omental biopsy. |

| Liu et al., 2015 (2 cases) | Case 1: 29Case 2: 28 | Case 1: abnormal vaginal bleeding associated with lower abdominal pain. Ectopic pregnancy.Case 2: ectopic pregnancy. | No data | Case 1: no dataCase 2: 5.0×5.0-cm | Case 1: well-defined solid massCase 2: heterogeneous solid mass | Case 1: Laparoscopic enucleationCase 2: laparoscopic tumor enucleation |

| Liu et al., 2017. (1 case) | 46 | No data | Elevated CA-125. | No data | Cystic-solid left pelvic mass and ascitis | No data |

| Marinho et al., 2021. (1 case) | 18 | Abdominal pain | Tumor markers were within normal limits. | 7.7×6.9×9.8cm | Cystic and solid mass with vascularization. | Laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Matsutani et al., 2018 (1 case) | 17 | Abdominal pain | AFP, CEA and CA19–9 was all within normal limitsCA-125: 76.3U/ml | 15cm | Multiseptated cystic mass | Oophorectomy and omentectomy. |

| Mensah et al., 2017. (1 case) | 32 | Menstrual irregularity and secondary infertility.Primary mesenteric extra gonadal sclerosing stromal tumor. | No data | 8.2×9.1×9.4cm | No data | Laparotomic excision. |

| Mokhtari et al., 2014. (1 case) | 45 | Hypermenorrhea and abdominal pain | LDH, CEA 1.9, AFP CA-19-9, CA-125 normal | 5×3.5×3cm | Solid echogenic mass | Laparotomic excision |

| Naidu et al., 2015 (1 case) | 14 | Virilization | β-HCG: <1miu/mlα-Fetoprotein: 2.9ng/ml, CEA: 1.3ng/ml | 12cm and 5cm | Large bilateral solid pelvic masses. Normal ovaries were not clearly identified | Laparotomic left salpingo-oophorectomy and right cystectomy. |

| Özdemir et al., 2016. (1 case) | Postmenopausal | Virilization | No data | 10×9×5cm | Encapsulated ovarian mass without any capsular breach | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Palmeiro et al., 2016 (1 case) | 20 | Pelvic pain. | AFP, CA 125, β-HCG within normal limits | 7.8cm | Solid hypoechoic tumor with regular borders, Color Doppler: multiple vessels inside the lesion, more numerous at the periphery and extending to its central portion | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Squilarro et al., 2018 (1 case) | 10 months | Precocious puberty | Gonadotropin, estradiol, and androgen levels were normal as well as ovarian tumor markers | 2.7×2.5×1.7cm | Solid, slightly heterogeneous lesion with associated color flow anterior to a normal-appearing uterus without clear visualization of either ovary. | Laparotomic salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Tomimatsu et al., 2016. (1 case) | 22 | Large abdominal solid mass | No data | No data | No data | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Uner et al., 2017. (1 case) | 29 pregnant | Intracesarean incidental finding | No data | 30cm | No data | Salpingo-oophorectomy. |

| Whang et al., 2022. (1 case) | 28 | Pelvic mass | Normal limits | 4.8×3.7cm | Cystic and solid mass in the left ovary | Laparoscopy |

| Yen et al., 2014 (1 case) | 9 | Virilization | B-HCG: 1miu/mlα-Fetoprotein: 1.3ng/mlCA 125: 17.5U/mlCEA 2ng/ml | 15×8.5×6cm | No data | Laparotomic salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Yesil et al., 2016. (1 case) | 17 | Abdominal pain. | No data | 5×4cm | No data | Laparoscopic excision |

| Zhai et al., 2015. (1 case) | No data | Severe preeclampsia | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Zhang et al., 2020. (1 case) | 26 | Pelvic pain | Ca 125 normal | 7×7×2cm | Hypoechoic and irregular mass in the left adnexal region. Well circumscribed with sparse-blood flow signals. | Laparotomic salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Zhang et al., 2020 (1 case) | 11 | Abdominal pain and menstrual irregularities | α-Fetoprotein: 14.03μg/LCEA 0.81μg/LCA 19-9: 10.50U/mlCa 125: 10.69U/mlHE4: 31.24pmTissue polypeptide antigen: 0.18ng/ml | 7.51×5.39×7.6cm | Predominantly solid in echotexture with a multiloculated cystic lesion | Laparoscopic cystectomy |

| Zhao et al., 2019. (1 case) | 70 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Serum estradiol: 49.78ng/L | 3×2cm | Laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy |

Clinically, SST usually present in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life, in contrast to other ovarian stromal tumors which present in the 5th or 6th decade. Most of the cases are unilateral.7,8 There are reports for extragonadal localizations.9,10

As in our cases, the most common symptoms are pelvic pain and menstrual irregularities. SST presenting with ovarian torsion were described in two reports.11,12 There are publications of SST in pregnant women.13,14 Bennett et al.13 reported 8 cases of pregnant women with SST and most of the cases were incidental findings during prenatal ultrasound follow up or at cesarean sections.

Similar to our first case, laboratory findings are nonspecific and tumor markers are often within normal limits, but elevated levels had been reported.15,16

SST are typically nonfunctioning, but there are publications reporting elevated levels of both estrogenic and androgenic hormones. Hormone production can cause irregular menses, amenorrhea, infertility, precocious puberty and virilization.17–19 The association with Meigs and McCune-Albright syndrome has been documented.20–22 Endometrial hyperplasia and postmenopausal bleeding concomitant with SST have been described.23,24

The etiology of SSTs is unknown. They were thought to arise from pluripotent immature stromal cells of the ovarian cortex.25 Some authors propose that they arise from the perifollicular myoid stromal cells.26 Other theories suggest that SSTs and thecomas are probably closely related entities as they share some morphological features and antigenic determinants.27 They are also thought to be developed from preexisting ovarian fibromas.28

Sclerosing stromal tumors have an edematous section surface with cystic changes. Microscopic examination shows a pseudolobular pattern, admixed spindled and rounded weakly luteinized cells, and prominent typically ectatic sometimes branching staghorn-like blood vessels.29 Histological features include a pseudolobular pattern with focal areas of sclerosis and 2 distinct cell populations of spindled and polygonal cells separated from each other by hypocellular, edematous, and collagenous stroma with thin-walled blood vessels.30 Immunohistochemical examination shows positivity for inhibin and vimentin, and negativity for S-100 protein and epithelial markers.11,31

As supported by our cases, a preoperative diagnosis of SST is challenging based on clinical and ultrasonographic findings. The differential diagnosis between SST and malignant tumors is difficult due to their ultrasonographic appearance. Differential diagnoses include other sex cord stromal tumors, such as fibroma, thecoma, lipoid cell tumors and metastases.8

Pelvic ultrasound, computed tomography and MRI imaging are useful for preoperative diagnosis of SST. Ultrasound is cost-effective and usually the first diagnostic approach to a pelvis mass.5 Gray scale ultrasound appearance of SST, described by Joja et al., is mainly a solid or multilocular unilateral cyst with cystic areas and acoustic shadowing.4 The importance of color Doppler with a high degree of peripheral and a slight central vascularization was described by Deval et al.5 On T2-weighted MRI images, signal intensities of the cystic components are high and those of the solid components are inhomogeneous. Dynamic MRI has a marked early enhancement of the solid components.4,32 The contrast enhancement pattern of SST of the ovary on dynamic CT and MRI is characteristic and involves peripheral contrast enhancement in the early phase after contrast material administration followed by centripetal progression in the delayed phases.33 Ultrasound elastography may be used as a complementary imaging technique to show the stromal component of SST with quantitative strain values.34

The treatment is surgical excision and a laparoscopic fertility sparing approach should be performed whenever it is possible.35 As in our cases, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, either via laparoscopy or laparotomy, is the most common surgical technique.

The strengths of our cases include the clinical and ultrasonographic description of a rare case of benign ovarian tumor with few annual publications. Comparison of our findings with review of the existing literature is provided. Limitation of our case reports is due to the retrospective design. Another limitation is the incomplete information in the second case description.

ConclusionAlthough SST are rare benign ovarian tumors, our study highlights the importance of consideration SST in the differential diagnosis of a unilateral, solid cystic, ovarian mass with a high degree of peripheral and a slight central vascularization in young female women. A preoperative diagnosis is usually difficult, but the familiarity with typical imaging presentation of SSTs allows an accurate preoperative diagnostic orientation and enables a less invasive surgery. Surgical resection of the tumor is curative, with no reported recurrences. Future studies with more cases will offer better insight into this rare entity.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article and that patients gave informed consent.

Patient consentPatient gave informed consent.

FundingThe authors have not received financial support to carry out the article.

Conflict of interestsThere is no conflict of interest.