Sexual dysfunction is one of the common findings among chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients and can lead to a decline in sexual desire, fertility/potency, successful pregnancy, along with menorrhagia and occasionally, amenorrhoea. Successful kidney transplantation is an effective method to preserve sexual desire in both the sexes and to achieve successful pregnancy where reasonable planning can give favorable outcomes for both mother and embryo. This review summarizes some common reproductive alterations in men and women undergoing renal transplant.

La disfunción sexual es uno de los hallazgos comunes entre los pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica y puede provocar una disminución del deseo sexual, de la fertilidad, de la potencia, de la posibilidad de embarazo, además de menorragia y, ocasionalmente, amenorrea. El trasplante de riñón exitoso es un método efectivo para preservar el deseo sexual en ambos sexos y recuperar la posibilidad de un embarazo, para el que una planificación razonable brindará resultados favorables tanto para la madre como para el embrión. Esta revisión ha resumido algunas alteraciones reproductivas comunes en hombres y mujeres tras un trasplante renal.

Sexual dysfunction is common among chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. About more than 50% of uremic men and women complain about their sexual desire and functionality. Women with CKD are also presented with amenorrhea and period without ovulation. Pregnancy-preservation measures are rarely used in dialysis patients because its likelihood is 1 in 200 patients.

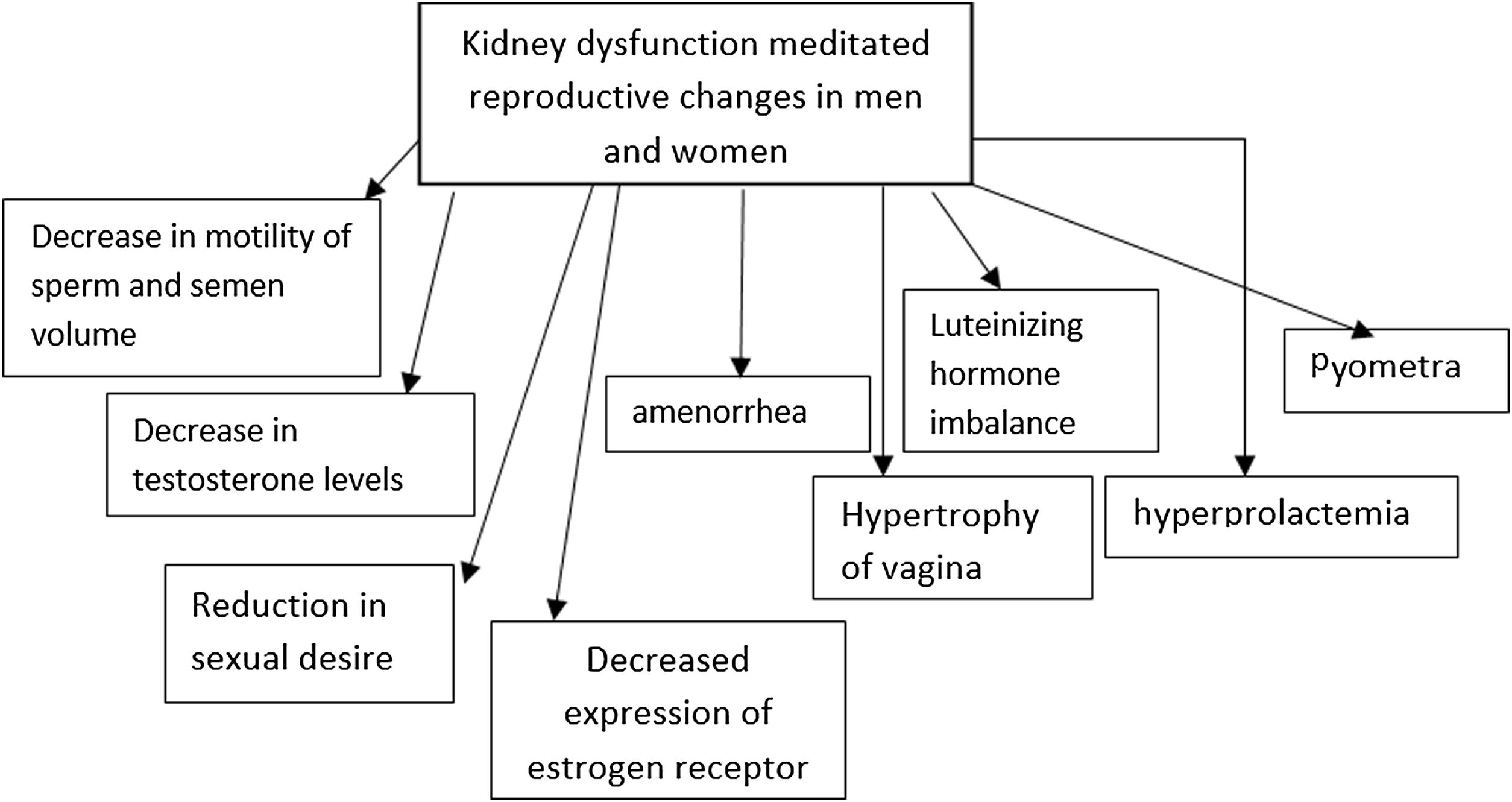

The cause of sexual dysfunction and infertility in both the sexes is multifactorial; therefore, structural, vascular and autonomous causes, as well as the consumption of certain drugs should, be studied that might lead to hormonal imbalance such as that of, prolactin, testosterone, estradiol.

Following successful kidney transplantation, sexual dysfunction and infertility is reported in 90% of the women at childbearing age; however, only 60% of these outcomes are seen in men. Total and free testosterone levels decline due to the reduction in the production by Leydig cells. Germinal Epithelium is also affected by hemodialysis; with the reduction of semen volume and sperm motility. In both, men and women, hemodialysis does not affect the pituitary and Gonadotropin response (LH, FSH), maintains the normal levels of GnRH (proportionate increase) whereas, LH levels are either normal or high and prolactin level rises up to 30% or 3–6 times as that of the baseline prolactin blood level; however, it is <100ng/ml due to reduced metabolic clearance and increased secretion of the pituitary hormones. Reduced libido, impotence and infertility are very common in men undergoing dialysis however, other etiologies like vascular deficiencies, anemia, fatigue, depression, autonomic neuropathies should also be considered when studying impotencies.1

In women undergoing hemodialysis, ovarian function and estradiol serum levels are normal. Furthermore, negative feedback, defined as FSH, LH increase following Clomiphene prescription (during menopause), is normal in hemodialysis patients while positive feedback is disrupted, i.e., FSH, LH do not increase with the administration of exogenous estrogen in the mid cycle (Fig. 1).

Almost 50% of hemodialysis women are presented with amenorrhea and 40% of those having irregular and anovulatory cycles. Menometrorrhagia is also less commonly seen whereas, infertility is common. Additionally, to have effective results from dialysis, good nutrition and sufficient erythropoietin and contraception are recommended.2,3 Administration of immunosuppressive drugs after pregnancy is associated with immune-related alterations such as; increased levels of IL-17 and natural killer cells, suppression of lymphocytes and structural changes in thymus and spleen. Nonetheless, proper selection of these drugs can be proven healthy for the baby and the mother.4

Alterations in reproductive hormone and sexual function in men after renal transplantationAfter a successful transplant,∼66% of men are reported to show improved libido and return of sexual function. However, in some cases, no libido improvement is observed, and worst is seen with time. Fertility is evaluated through sperm count that improves in 50% of the patients following the transplantation, marked by the normalization of sexual hormones, increase in the levels of testosterone and FSH and subsequent reduction or normalization of LH hormone (increased in kidney patients). Use of immunosuppressant drugs, following kidney transplant such as, calcineurin inhibitors, cyclosporine A and tacrolimus can also affect male reproductive abilities.5 Cyclosporine disrupts the biosynthesis of testosterone by damaging Leydig and germ cells, respectively and directly impairs the hypothalamus–pituitary–gonadal axis.6

Nonetheless, transplantation in men does not correspond to malformations in neonates.7

Changes in sex hormones and pregnancy outcomes in women after kidney transplantAnimal studies have revealed that kidney dysfunction, particularly CKD, is correlated with hypertrophy of vagina, infection of the uterus (pyometra) caused by inflammation and fibrosis in reproductive parts. The expression of estrogen receptors in the kidney is also compromised in these patients.8

Renal transplant and hemodialysis are also marked with normalization of ovarian reserve, seen by the increase in the anti-Müllerian hormone concentration.9–11 Hyperprolactemia and reduction in the secretion of luteinizing hormone, due to the disturbance in estradiol-mediated feedback, are common in females presenting renal anomalies. However, following kidney transplant, safer and healthier pregnancy has been reported.10,12,13

After a successful transplant, fertility returns to the normal state along with reproduction cycles and ovulation, mediated by the decrease in prolactin levels (Table 1).

Summarizes commonly reported effects of immunosuppressive drugs during and after pregnancy in parents and child.

| Immunosuppressive drugs | Effects on parents and/or child |

|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | ADHD in childrenPremature neonatal thymusAdrenal hypoplasia, cleft palate and mental retardation in babyPreterm birthMiscarriage |

| Azathioprine | Low birth weightSmall gestational agePreterm birthJaundice, leukopenia, cleft palate, myocardial dysfunction and respiratory distress syndrome in baby |

| Cyclosporine | Low birth weightDiabetes, hypertension and graft failure in motherPreeclampsiaTestosterone dysfunctionImpairment of hypothalamus–pituitary–gonadal axis |

| Tacrolimus | Not associated with major complicationsNo strong evidence regarding congenital malformation is seen |

| Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin | Teratogenic effectsFetal malformationEveroliums can be taken by breast-feeding mothers |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Fetal malformationsStructural defectsMiscarriagesNephrotoxic |

Renal transplant women have 10-fold greater odds of delivering alive child, than those under dialysis.14 The effects of renal function on pregnancy and the chances of losing the graft are some of the most raised concerns in kidney transplant candidates. A large number of cases have reported successful renal transplantation leading to the normal hormonal function and fertility retrieval in 90% of women at childbearing age, within six months. Additionally, pregnancy does not seem to impose irreversible complications when pre-pregnancy kidney function is stable.15

In a Cohort report in the UK with 79% live births and a two-year renal transplant survival, pregnancy outcomes in 183 patients (1998–2001) was 94%, compared to 93% in the control group.

Based on mono-variant analyzes, control of hypertension during pregnancy and graft survival are correlated; however, in pre-pregnancy with creatinine (Cr)>1.7, post-pregnancy Cr levels are likely to increase.16,17 An increase in glomerular function rate (GFR) is reported in pregnancy but hyperfiltration is flow-dependent and does not increase intraglomerular pressure. The outcome of pregnancy is associated with the transplanted kidney function before pregnancy and if Cr<1.4, the chances of a successful pregnancy are up to 96%. 70–75% cases of Cr<1.4 are seen to conceive successfully, nonetheless, 1/3rd of the pregnancies is accompanied with spontaneous or therapeutic abortion. The main cause of the deterioration in the kidney function is preeclampsia, acute or chronic rejection of transplantation, relapsing renal diseases, dehydration and urethral obstruction due to pregnancy, infection and drug toxicities.17 A study has also shown that long term survival of transplanted kidney is not affected by pregnancy.18

The first successful post-transplant pregnancy reported (1958) was a case of homogeneous twin sisters. Following advancements in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive drugs as well as improvement of survival elongation and quality of life in kidney transplant patients, the number of women at childbearing age, conceiving pregnancy after kidney transplant has increased.19 Almost 1 out of 50 women at reproductive age undergoing kidney transplant, report pregnancies without complications however, blood pressure should be controlled and owing to the high risk of infection, a detailed examination should be performed at each visit.20

A successful pregnancy is observed in 90% of transplant cases after the first trimester; however, 74% of the pregnancies in transplant recipients are successful. Nevertheless, 22% of pregnancies in transplant recipients terminate in the first trimester, 13% is due to spontaneous abortion and 9% are elective abortions. Low birth weight risk is increased in transplant recipients’ pregnancies (25–50%) and preterm deliveries are also observed in 30–50%. Furthermore, ectopic pregnancy rate is slightly higher in kidney recipients, especially immediately after transplantation; and the risk is less than 1%.

In a recent meta-analysis, it is reported that the rate of live births 3-years after renal transplant in less than 3 years, with greater incidence of spontaneous abortion and complications.21

Effects on neonatesNeonatal structural defects in infants of kidney recipients are no more than the general population. Pregnancy within 6–12 months after transplantation is not recommended due to acute rejection or risk of infection. Traditionally, it is recommended to postpone pregnancy two years after the transplant; however, taking into account the age and the possibility of decline in fertility, one-year interval is recommended for safe pregnancy, provided that the kidney function is normal and there is no episode of acute rejection despite the rate of acute transplant rejection is similar to non-pregnant patients (3–4%).

Effects of renal transplant drugs on pregnancy outcomeGlucocorticoidsGlucocorticoids, such as prednisone & prednisolone, can get through the placenta; and the ratio of cord drug level to the mother's blood is 1–10.22 Normally, glucocorticoids levels are low in the fetus as compared to mothers, therefore, a slight increase in the concentration can lead to adverse effects.23 Prenatal exposure of the child to glucocorticoids can also lead to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children at the age of 10 years.24 Similarly, a high concentration of glucocorticoids (above 15mg) can lead to premature neonatal thymus, adrenal hypoplasia, preterm birth, and miscarriages.25 They are likely to alter intrauterine growth and babies are reported with cleft palate and mental retardation.23 Steroids can cause premature amniotic membrane rupture and hypertension; doses>20mg increase the risk of infection in mothers. The administration of these drugs can also affect renal function during pregnancy.26

The incidence of acute rejection in pregnant and non-pregnant kidney recipients is similar; however, diagnosing acute rejection is more difficult during pregnancy and high dose steroid therapy is considered as the basic treatment.27,28

AzathioprineAzathioprine (AZA) is commonly prescribed for kidney recipients during pregnancy. Studies exploiting radioactive-labeled Azathioprine show that 64–93% of the azathioprine appears as inactive metabolites in fetal blood.29 In general practice, its dose is reduced during pregnancy since it carries the risk of low birth weight, small gestational age, and preterm birth.30 In adults, azathioprine is metabolized to 6MP (6 mercaptopurine); following inosinate pyrophosphorylase deficiency (due to the immature liver of fetus) required for the conversion of azathioprine to 6MP (active metabolite), the fetus is protected against the effects of drugs. Azathioprine doses>6mg/kg is teratogenic in animal studies.

In human studies, LBW, prematurity, jaundice, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and aspiration have been observed. Azathioprine causes myelosuppression (suppressed bone marrow) in the fetus, and in cases where maternal leukocyte count<7500/mm3, infants are also at the risk of leukopenia.31 Interestingly, paternal (father) use of AZA is also characterized by congenital abnormalities.32 Preterm birth, abortions, cleft palate and lip and cardiac anomalies are also reported with the use of azathioprine.33

CyclosporineAnimal studies have shown that cyclosporine would rarely pass through the placenta and has no effect on organogenesis; however, some cases of tubule cell damage are reported in rats.34,35

In human studies, the administration of cyclosporine is associated with LBW, hypertension, diabetes, and failure of mother's allograft. Cyclosporine metabolism increases during pregnancy and higher doses are required to maintain stable therapeutic serum drug levels.36

Some pregnant women who undergo cyclosporine treatment develop preeclampsia; due to the increased production of thromboxane and endothelin which are leading pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Thus, many physicians suggest the usage of cyclosporine at 2–4mg/kg per day.37 Reggia, Bazzani38 concluded that usage of cyclosporine conveys up to 85% of live and healthy birth therefore, is not associated with any serious complications.

TacrolimusThere is little information on the effect of tacrolimus on pregnancy. Hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme is inhibited during pregnancy which increases tacrolimus blood levels. Therefore, tacrolimus dosage should be considerably reduced to prevent toxic effects. In a study (60% dose reduction) conducted on 100 pregnant women, including 27% transplant recipients under tacrolimus treatment, there were 68 live births where, 60% of those were premature.39

Akturk and colleagues Akturk, Celebi40 suggested that the dose of tacrolimus should be slightly increased during pregnancy to avoid complications. Comparative studies have shown that its side effects are less severe than that of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).41

Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycinInvariant with calcineurin inhibitors, sirolimus and everolimus (mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor) have lesser nephrotoxic effects. Its metabolism is supported by CYP3A 4/5, CYP2C8, and multidrug-resistant protein. Its general use is characterized by hematological and metabolic side effects such as; thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, hyperlipidemia, proteinuria and diarrhea.42 Similarly, everoliums inhibits proliferation of B and T lymphocytes and inhibits the progression of the cell cycle.43

Sirolimus is contraindicated in pregnancy because of its teratogenic effects as well as the risk of fetal malformations caused by sirolimus, especially during 30–71 days of the gestational age, associated with the highest risk. In a female kidney recipient at childbearing age, not under any contraception, Sirolimus should be discontinued preemptively (at least 12 weeks before pregnancy).

A case study reported a 33-year-old female who underwent kidney transplantation, was initially administered tacrolimus, MMF, and glucocorticoid. However, due to severe side-effect when regime was changed to everolimus, and azathioprine, in addition to glucocorticoid, successful and healthy pregnancy with a gestational age of 39 weeks was conceived.43 Additionally, breastfeeding from mothers under everoliums is also recommended possible and safe.44

Mycophenolate mofetilMMF is a prodrug that is metabolized into mycophenolic acid, is contraindicated during pregnancy due to the reported fetal malformations, structural defects, miscarriages, and deaths in human and animal studies.33 However, a recent study has reported successful administration of MMF in pregnancy; yet, since there is a lack of reliable information, MMF is not recommended.45 MMF can reduce the frequency of abortions and complications during pregnancy in transplant recipients, according to some evidences.46 However, it can also lead to apoptosis and histological abnormalities in the kidney during pregnancy.26 Furthermore, MMF is also associated with a reduction in the frequency of live births and malformations.41

OKT & polyclonal antibodiesOKT3 is an immunoglobulin G (IgG) that passes through the placenta. National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR) has reported 4 live births in 5 pregnant females who were administered OKT3 to treat acute rejection. The effect of polyclonal antibodies on fetal development is unknown however, it is known that IgG can cross the placenta.

Management of pregnancy after transplantationContraception counseling should be performed immediately after transplantation because ovulation cycles get back to normal in women with the normal kidney function within 1–2 months post-transplantation. Low doses of estrogen and progesterone are recommended for contraception. Due to human immunodeficiency, the risk of infection increases following the use of intrauterine device however, its efficacy decreases because of the anti-inflammatory impact of immunosuppressive drugs.47

The criteria in recipients considering pregnancy are:

- 1.

Pregnancy at least one year after kidney transplant

- 2.

Stable kidney function (Cr<2)

- 3.

No episode of acute rejection

- 4.

Blood pressure≤90/140 during the course of drug consumption (systolic blood pressure<140)

- 5.

Proteinuria≤500mg/day

- 6.

Prednisolone≤15mg/day

- 7.

AZA≤2mg/kg

- 8.

Cyclosporine≤4mg/kg

- 9.

Normal sonography of transplanted kidney.48

The most common complication of pregnancy in renal transplants is hypertension, which occurs in 30–75% of the patients due to a combination of underlying disease and intake of calcineurin inhibitors. Preeclampsia occurs in 25–30% of pregnant transplant patients and is distinguished by the prevalence of hypertension and baseline proteinuria. American Society of Transplantation recommends invasive treatment of hypertension aiming at managing blood pressure in pregnant transplant patients at near-normal levels and less than in non-pregnant hypertension cases.

Blood pressure control in pregnant transplant patients with mild to moderate hypertension should be closely monitored and if signs of preeclampsia appear, delivery must be performed at 37 weeks. Precise management of blood pressure is required for renal transplant patients, undertaking pregnancy49 Choice Drugs (optional) for blood pressure control in pregnant transplant patients are methyldopa, calcium channel blockers, and labetalol. These drugs are associated with the increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and the corresponding expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase hence, playing a significant role in enhancing the interaction of trophoblast and endothelial.50

Anti-hypertensive drugsMethyldopaThe drug is safely and effectively used in a number of randomized studies and its usage has been increasing periodically.51 In CHIPS clinical trial, methyldopa is associated with lesser severe side effects such as; hypertension, low birth weight, and preeclampsia as compared to labetalol.52 It is not seen to impose any teratogenic risks.53

Beta-blockersCardiovascular β-blockers such as atenolol and metoprolol are not contraindicated in late pregnancy but may cause fetal growth retardation in mid-pregnancy and multicystic renal dysplasia.54 Non-selective β-blockers should not be used because of the uterine contractions. Administration of beta-blockers at the early stage of pregnancy also increases the risk of bradycardia, hypoglycemia and cardiogenic defects in newborn.55,56

Labetalol is an effective antihypertensive beta-blocker drug like methyldopa; however, few studies have been conducted on the effects on children born to women who were administered labetalol.57 A comparative analysis has shown that is less severe hypertension, labetalol is more effective than hydralazine.58

Calcium channel blockersNifedipin, nicardipin and verapamil are used in severe pregnancy hypertension and are not seen to be associated with an increase in congenital anomalies and complications, even in the first trimester.59 The efficacy of these drugs is similar to that of labetalol.60

These drugs may intensify the effects of hypotension and magnesium-induced neuromuscular blockage in women with preeclampsia.

Bacterial infectionsUrinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common bacterial infection in pregnant transplant women reported in up to 40% women. It is prevalent in end-stage renal disease patients with pyelonephritis. Urine culture of these patients should be monthly performed and in the case of bacteriuria with unknown causes, patients should be treated for two weeks and receive long-acting antibiotics (suppressive) until delivery.

In the case of requiring invasive monitoring of the baby through scalp electrodes or fetal intrauterine pressure measurement, antibiotic prophylaxis would be given where toxic effects of the choice antibiotics on the fetus should be considered. Penicillin does not lead to cross-reaction with the metabolism in eukaryotes and can be the antibiotic of choice.61

Viral infectionsCytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common post-transplantation viral infection.

Transplant patients are recommended to try pregnancy at least 1 year after kidney transplantation; in the meantime, the peak CMV infection will pass. Fetal infection is diagnosed by culturing amniotic fluid. Nonetheless, prescribing Ganciclovirs twice a day has caused birth defects in animals.62

Herpes simplex infection (HSV) leads to miscarriage before 20 weeks. If the culture is positive for HSV cervix, Cesarean section should be done to prevent the delivery of neonatal herpes. Acyclovir can also be safely used during pregnancy.

Infants born to mothers with positive hepatitis B surface antigen should receive hepatitis B immunoglobulin within 12h after birth and hepatitis B vaccine within 48h of birth at a separate site (with 1- and 6-month boosters). The combination of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and vaccine provides a 90% protective effect against hepatitis B virus.

Vertical transmission of hepatitis C from a mother to an infant is less than 7%, unless it is accompanied by human immunodeficiency virus infection.63

Delivery and postnatal effectsVaginal delivery is recommended in transplant patients unless standard cesarean section (C-section) indications are present since C-section can be associated with trauma to newly transplanted kidney and ureter. Infections and overloads should be observed, and minimum manipulation should be done. Successful C-section is reported in heart and kidney transplant recipients.64

Patients with renal dysfunction are at risk of water retention due to oxytocin intake. In the perinatal period, a stress steroid dose should be injected to prevent acute rejection after pregnancy.

Hydrocortisone 100mg is also recommended every 6h (even during labor). Moreover, breastfeeding in patients taking certain immunosuppressive drugs should be discontinued. The average breast milk cyclosporine level is 0.84 compared to the blood and can be toxic for the baby. Similar findings have been reported for other immunosuppressive drugs including tacrolimus.65

Renal transplant patients with end-stage renal disease have greater odds of conceiving healthier and safer pregnancy, as compared to those undergoing dialysis.66-69

ConclusionThis review has summarized some common reproductive alterations in men and women, undergoing renal transplant. Analysis of literature has brought us to the conclusion that pregnancy after kidney transplant is entirely possible. However, the administration of immunosuppressive drugs might impose pathological and congenital effects on mother and child. Clinicians are, therefore, recommended to keep such patients under close monitoring for the adjustment of drug dose, nephrotoxicity, contraindications of the drugs and infections after kidney transplant in order to deliver a healthy baby.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Authors’ contributionsDr. Ziba Aghsaeifard: conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Dr. Masoumeh Ghafarzadeh: Designed the data collection instruments, collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Dr. Reza Alizadeh: Coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all

aspects of the work.

Human and animal rightsNo animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Consent for publicationInformed consent was obtained from each participant.

Availability of data and materialsAll relevant data and materials are provided with in manuscript.

FundingNo funding was secured for this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors deny any conflict of interest in any terms or by any means during the study.