With diagnostic and treatment advancements in cancer management, the need for improvement of survivors’ quality of life has been increasing. One of the issues affecting the quality of life in gynecologic cancer survivors is a decline in their sexual function, which is affected in many ways. In order to assess sexual dysfunction in gynecologic cancer survivors.

ObjectiveThis study is designed to assess different areas of sexual function including desire, arousal, vaginal lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain.

Materials and methodsPatients who had completed treatment since 6 months to 6 years ago included in the case–control study starting from January 2019 to January 2020. Twenty-nine sexually active gynecologic cancer survivors with sexual dysfunction were enrolled as cases and 91 sexually active ones without sexual problems were assigned to the control group. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire consisting of 19-items and six areas was completed for each participant.

ResultsAverage sexual dysfunction score of the case group was 16.78 with cut-off point of 28 for dysfunction. The most common domain of sexual dysfunction was pain (96.55%), followed by sexual arousal (86.21%), vaginal lubrication (72.41%), orgasm (72.41%), satisfaction (65.52%) and sexual desire (55.17%).

ConclusionIn gynecologic cancer survivors, sexual dysfunction was directly related to employment, brachytherapy and co-existing DM and inversely related to the time elapsed since cancer diagnosis and menopause. Asking about sexual problems and referral to a specialist should be included in the patient treatment process.

Con los avances en el diagnóstico y tratamiento del cáncer, la necesidad de mejorar la calidad de vida de los sobrevivientes ha ido en aumento. Uno de los problemas que afectan la calidad de vida de las sobrevivientes de cáncer ginecológico es la disminución de su función sexual, que se ve afectada de muchas maneras.

ObjetivoCon el fin de evaluar la disfunción sexual en sobrevivientes de cáncer ginecológico, este estudio está diseñado para evaluar diferentes áreas de la función sexual, incluido el deseo, la excitación, la lubricación vaginal, el orgasmo, la satisfacción y el dolor.

Materiales y métodosPacientes que habían completado el tratamiento desde hacía seis meses a seis años, incluidas en el estudio de casos y controles a partir de enero de 2019 a enero de 2020. Veintinueve sobrevivientes de cáncer ginecológico sexualmente activas con disfunción sexual se inscribieron como casos y 91 sobrevivientes sexualmente activas sin problemas sexuales fueron asignados al grupo de control. El cuestionario del Índice de Función Sexual Femenina (FSFI) que consta de 19 ítems y seis áreas se completó para cada participante.

ResultadosLa puntuación media de disfunción sexual del grupo de casos fue de 16,78 con un punto de corte de 28 para disfunción. El dominio más común de disfunción sexual fue el dolor (96,55%), seguido de excitación sexual (86,21%), lubricación vaginal (72,41%), orgasmo (72,41%), satisfacción (65,52%) y deseo sexual (55,17%).

ConclusiónEn las sobrevivientes de cáncer ginecológico, la disfunción sexual estuvo directamente relacionada con el empleo, la braquiterapia y la DM coexistente e inversamente relacionada con el tiempo transcurrido desde el diagnóstico del cáncer y la menopausia. La consulta sobre problemas sexuales y la derivación a un especialista deben incluirse en el proceso de tratamiento del paciente.

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is demarcated as lack of sexual desire, excitement (arousal), lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, or having painful coitus. The occurrence of FDS can be influenced by a sort of anatomical, physiological, mental, social, and cultural features, and it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life and interpersonal relationships.1 The presence of an excellent physical, emotional and mental state with regards to sexuality, is how sexual health is defined by World Health Organization; the presence of related diseases is a part of but does not define a sexual dysfunction or impotence.2

In recent times, advancements in cancer diagnosis have resulted in improved cancer survival rates. Gynecologic cancers (GCs) have high incidence rates (constituting approximately 15% of all new female cancer cases in 2020); improvements in survivors’ quality of life are noted to rise every day.3 The discovery of a cancer diagnosis is a distressing and anxiety-provoking experience, which negatively affects a patient's personal and family life and sexuality. Various socio-economic, marital, and psychological issues are encountered by the sufferers.4,5 Of the long-lasting complications of GC treatment, FDS is one of the commonest.1 In a study, FDS was diagnosed in 62% of patients with GC after recovery.6 In a systematic review conducted in 2016, FSD was found to have a prevalence of over 60% amongst all cancer patients, with GC having the highest rates.7 Hormonal changes, injury to pelvic nerves, and surgical resection of sexual organs (e.g., uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and cervix) are some of the possible outcomes of GC treatment. Chemotherapy can lead to loss of libido, and result in physical limitations such as fatigue and weight changes; on the other hand, chemotherapy can induce disorders such as temporary or permanent premature ovarian dysfunction, thus decreasing estrogen production and diminishing sexual desire. Cancer therapies including induced menopause, surgery, chemotherapy and pelvic radiotherapy can result in vulvovaginal atrophy, a condition resulting in sexual dysfunction.8 Pelvic radiotherapy, an integral part of the management of many gynecological cancers, can result in late complications by damaging vaginal tissue, nerves, and blood vessels, resulting in the development of vaginal fibrosis and stenosis and affecting clitoral sensitivity.9,10 Such late complications may appear years after completion of treatment, affecting the patient's quality of life.11

Consideration has seldom been paid to sexual problems in cancer survivors.12 Improved sexual health outcomes can be expected by owning strategies such as physician-led discussion of sexual matters early in the course of treatment and ensuring adequate communication as well as provision of information, support, and interventions related to sexual dysfunction. In order for a patient to make informed decisions about her treatment, it is necessary that the different aspects of treatment options, including their effects on sexuality are discussed before commencement of therapy.13,14 Exploring and addressing patients’ concerns about sexuality and accordingly reviewing the proposed therapy, improves the quality of patient care provided.14

The current research is designed to study the prevalence of FSD and its different aspects, in patients treated for GC with modalities such as surgery, pelvic radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or chemotherapy. It also compares the effects of various methods of treatment on patient's quality of sexual function.

Materials and methodsIn this case–control study two hundred and eighty-one participants, survivors of GC, from the gyneco-oncology clinic of Imam Hossein Medical Center and the Shohada Tajrish Hospital Radiotherapy Clinic, Tehran, Iran were evaluated. Patients who had completed treatment since 6 months to 6 years ago included in study starting from January 2019 to January 2020. Participants filled a questionnaire related to demographic information, as well as a cancer survivor's assessment questionnaire from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).15 Participants were in the recovery phase and at least six months have passed since their treatment completion. From sexually active participants, the patients who reported sexual problems were enrolled as the cases, and the patients without sexual problems entered the study as the control group. These two groups had their sexual function questionnaires filled.

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) is a questionnaire containing 19 items from six domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI is a quick tool of thoroughly assessing the essential aspects of female sexual function.16 The sexual function questionnaire was completed during face-to-face interviews with participants. After collecting the information, the scores of the FSFI questionnaire were calculated according to the guidelines provided by the questionnaire designer organization. In this questionnaire, the standard score of the Female Sexual Function Index is the score that a person gives to the 19 questions. The scoring of the questionnaire is based on the Likert scale and is described next to the questions.16 Regarding the scoring method, each domain's score was attained by the addition of scores for the questions of each area and multiplying it by the coefficient provided for that domain.

The number of questions and coefficient of each domain, were as follows: In the ‘sexual desire’ domain, two questions were asked regarding frequency and intensity of sexual desire in the last four weeks, with a coefficient of 0.6. For ‘sexual arousal’, the four questions asked were about the frequency and intensity of sexual arousal, sexual confidence, and satisfaction; it had a coefficient of 0.3. In the field of ‘vaginal lubrication’, four questions were asked about frequency and difficulty in vaginal lubrication and in maintaining the lubrication, with a coefficient of 0.3. For the ‘orgasm’ domain, three questions were asked, including frequency and difficulty in achieving orgasm and satisfaction in maintaining orgasm with a coefficient of 0.4. For ‘sexual satisfaction’ also three questions were asked, but with a coefficient of 0.4; this domain questioned the level of satisfaction from the emotional intimacy in sexual contact, a satisfaction of sexual intercourse, and the overall satisfaction with sexual life. The domain of ‘pain’, which had three questions and a coefficient of 0.4, asked about the frequency and intensity of pain during and after sexual intercourse. The answer to each question was scored from 1 to 5 points based on responses provided, and in case of no sexual activity, a score of zero was considered.

By multiplying the obtained scores in each domain with the domain-specific coefficient, the final score for that domain was obtained. By the addition of the final scores of the six domains together, the full-scale score was obtained. Based on the weighting of the fields, the maximum score for each field is 6 and for the whole scale is 36. Higher FSFI scores indicate better sexual function. The cut-off point for dysfunction is equal or less than 28 for the whole scale and 3.3 for desire, 3.4 for sexual arousal, 3.4 for lubrication, 3.4 for orgasm, 3.8 for satisfaction, and 3.8 for pain. Scores higher than the cut-off point indicate good performance. Scores less than or equal to 28 have 77% sensitivity and 85% specificity for the clinical diagnosis of sexual dysfunction. Patients who answered positively to the question «having any concerns regarding sexual function» of the NCCN 2020 questionnaire proceeded to fill the FSFI questionnaire; all of those who had a scored less than 28 in the FSFI questionnaire, were regarded as having sexual dysfunction.22,23 We examined various variables, including age, length of diagnosis, parity, occupation, education, and comorbid underlying diseases in individuals with and without sexual dysfunction.

In a study by Rosen et al.,16 the reliability of the FSFI questionnaire was assessed by performing a test–retest analysis on a sample of 259 people aged 21–69 years, for the overall score (r=0.88) and for each sexual domain (r=0.79–0.86). They reported a high validity for the test.16 This questionnaire was used in a previous study with minor changes, and the degree of reliability was determined by retesting two weeks later (92%).17

Ethical considerationsThe study followed the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Board of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Ethical code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1398.449). All information about the women was kept fully confidential and all information was released as a group without the use of participant names. The participants incurred no costs and the study protocol did not harm the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and the details and purpose of the study were disclosed to them. This study does not contain any intervention with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Statistical analysisThe continuous variables were expressed as the mean±SD, and the categorical variables were presented as a percentage. Chi-square and independent t-test were used to compare data between the two groups. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 16.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). A «p value» less than 0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsOut of 281 patients evaluated in this study, 120 (42.7%) were sexually active, and 161 patients (57.2%) denied having sexual relations. Among sexually inactive patients, seven (4.3%) accused pain, and 154 (95.7%) mentioned that they did not have a sexual partner. Of the 120 sexually active patients, 29 (24.1%) had sexual dysfunction were enrolled as the cases, and 91 (75.8%) no sexual problems as the control group (Algorithm 1). Average sexual dysfunction score of the case group was 16.78 with cut-off score of 28 defined as dysfunction (Table 1). The most common domain of sexual dysfunction was seen in the area of pain (96.55%), followed by sexual arousal (86.21%), vaginal lubrication (72.41%), orgasm (72.41%), satisfaction (65.52%) and sexual desire (55.17%) (Table 1). The mean ages for patients with and without sexual dysfunction were 45.34±8.16 and 47.09±8.27, respectively. The mean age of two study groups was statistically similar (p value=0.323). Also, parity and education level of the two groups of patients were not significantly different. Likewise, the average age at the time of cancer diagnosis was not significantly different between the two groups (p value=0.32). In general, sexual dysfunction was significantly more common among employed patients (p value=0.008), and in patients with a median time of one year in comparison to two years after cancer diagnosis (p value=0.032).Algorithm 1Frequency of sexual activity and sexual dysfunction in gynecologic cancer survivors

Description of overall and different areas of sexual dysfunction among patients with sexual dysfunction.

| Average | Standard deviation | Lowest–highest | Cut point | Number of patients with dysfunction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire | 2.92 | 1.02 | 1.20–4.20 | 3.3 | 16(55.17) |

| Arousal | 2.71 | 1.01 | 1.20–5.10 | 3.4 | 25(86.21) |

| Lubrication | 2.96 | 0.609 | 1.50–4.20 | 3.4 | 21(72.41) |

| Orgasm | 3.19 | 0.817 | 1.20–4.00 | 3.4 | 21(72.41) |

| Satisfaction | 3.19 | 1.26 | 1.20–4.80 | 3.8 | 19(65.52) |

| Pain | 2.32 | 1.01 | 1.20–6 | 3.8 | 28(96.55) |

| Overall | 16.78 | 4.18 | 7–26.50 | 28 | 29(100) |

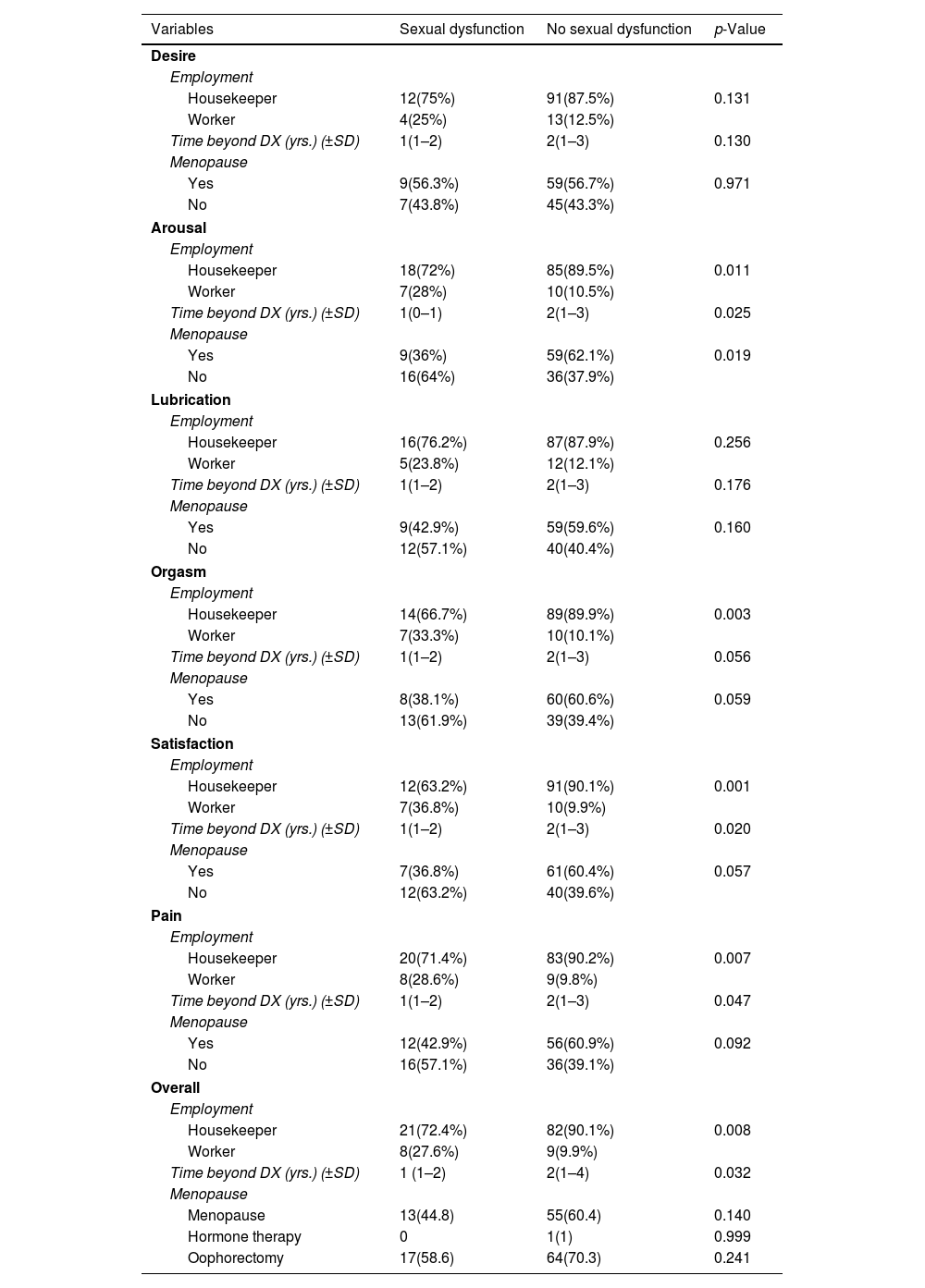

Regarding the impact of menopause on overall sexual function in three menopausal categories, (menopaused, hormone-treated patients, and oophorectomy patients), there was no significant difference between the two study groups (p value=0.14, 0.99, 0.24) (Table 2). Underlying diseases, including hypertension, psychiatric disorders, cardiovascular diseases and hypothyroidism, were not significantly different in-patient groups, nor in the six main areas of sexual dysfunction. Regarding diabetes mellites (DM), in general, there was no significant difference between the two groups (p value=0.35) (Table 2). Out of the 120 sexually active patients, 104 had no dysfunction in their sexual desire, while the remaining 16 had FDS in sexual desire domain. In this latter group, 37.5% (6 cases) were noted to suffer from DM, while this was the case in only 15.4% (16 cases) of the former group (p value=0.04). Thus, DM was noted to be significantly more common in patients with impaired libido compared to those with normal sexual desire function.

Coherence of employment, time beyond diagnosis, and menopause in different sexual dysfunction areas.

| Variables | Sexual dysfunction | No sexual dysfunction | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desire | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 12(75%) | 91(87.5%) | 0.131 |

| Worker | 4(25%) | 13(12.5%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1(1–2) | 2(1–3) | 0.130 |

| Menopause | |||

| Yes | 9(56.3%) | 59(56.7%) | 0.971 |

| No | 7(43.8%) | 45(43.3%) | |

| Arousal | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 18(72%) | 85(89.5%) | 0.011 |

| Worker | 7(28%) | 10(10.5%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1(0–1) | 2(1–3) | 0.025 |

| Menopause | |||

| Yes | 9(36%) | 59(62.1%) | 0.019 |

| No | 16(64%) | 36(37.9%) | |

| Lubrication | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 16(76.2%) | 87(87.9%) | 0.256 |

| Worker | 5(23.8%) | 12(12.1%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1(1–2) | 2(1–3) | 0.176 |

| Menopause | |||

| Yes | 9(42.9%) | 59(59.6%) | 0.160 |

| No | 12(57.1%) | 40(40.4%) | |

| Orgasm | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 14(66.7%) | 89(89.9%) | 0.003 |

| Worker | 7(33.3%) | 10(10.1%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1(1–2) | 2(1–3) | 0.056 |

| Menopause | |||

| Yes | 8(38.1%) | 60(60.6%) | 0.059 |

| No | 13(61.9%) | 39(39.4%) | |

| Satisfaction | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 12(63.2%) | 91(90.1%) | 0.001 |

| Worker | 7(36.8%) | 10(9.9%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1(1–2) | 2(1–3) | 0.020 |

| Menopause | |||

| Yes | 7(36.8%) | 61(60.4%) | 0.057 |

| No | 12(63.2%) | 40(39.6%) | |

| Pain | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 20(71.4%) | 83(90.2%) | 0.007 |

| Worker | 8(28.6%) | 9(9.8%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1(1–2) | 2(1–3) | 0.047 |

| Menopause | |||

| Yes | 12(42.9%) | 56(60.9%) | 0.092 |

| No | 16(57.1%) | 36(39.1%) | |

| Overall | |||

| Employment | |||

| Housekeeper | 21(72.4%) | 82(90.1%) | 0.008 |

| Worker | 8(27.6%) | 9(9.9%) | |

| Time beyond DX (yrs.) (±SD) | 1 (1–2) | 2(1–4) | 0.032 |

| Menopause | |||

| Menopause | 13(44.8) | 55(60.4) | 0.140 |

| Hormone therapy | 0 | 1(1) | 0.999 |

| Oophorectomy | 17(58.6) | 64(70.3) | 0.241 |

DX: diagnosis; Yrs: years; SD: standard deviation.

In the study of FSD and its six areas, housewives had significantly less FSD in the areas of sexual arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, pain, and overall sexual dysfunction, compared to employed women (Table 2). Similar results were noted in individuals in whom two years have passed since their cancer diagnosis, compared to those who were 1-year post-cancer diagnosis (Table 2). In the sexual arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction domains, postmenopausal people had significantly fewer sexual dysfunctions compared to non-menopausal patients (Table 2). Of the 19 people with FSD in the area of satisfaction, 14 (73.7%) had received brachytherapy. Out of 101 patients without dysfunction in satisfaction domain, 49 (48.5%) had received brachytherapy. thus, a significant relationship was observed between brachytherapy and dysfunction in satisfaction domain, with p value of 0.044 (Table 2).

DiscussionIn the present study, from 161 sexually inactive GCs (57.29%), 7 (4.3%) denied sexual activity due to pain, and 154 (95.6%) due to lack of a sexual partner. Of 120 (42.7%) sexually active survivors of GC, 29 (24.1%) had FSD. A recent study revealed sexual inactivity among 59% of patients after treatment for their GC, indicating high rates of persistent functional sexual problems in this group.18 Physical consequences of GC treatments such as sex organ removal and alopecia, combined with the psychological complications of such treatment such as damaged body perception, anxiety, and mood disorders, can damage patient's sexual function and act as a source of agitation, aggression, and depression in this population.19,20 Fear and anxiety caused by GCs and their treatments have shown, in previous studies, to be reasons behind patient reluctance towards sexual life. Resultingly, GC survivors may lose their sexual partner, or may not find one. In order to avoid rejection, many cancer patients, physically and emotionally distance themselves from their partners.21 Such unfortunate consequences damage the relationship between spouses, leading to lack of sexual satisfaction, and resulting FSD.19 As a study conducted in 2009, great fear and anxiety were experienced by hysterectomized patients about having sex, due to concerns about harming themselves and their partner. Concerns about negative effect of sex in worsening cancer or causing its recurrence can result in decreased libido, thus damage sexual function.22

Most cancer patients in the present study were women of childbearing age, with the mean patient age of 45.34 years, and the mean age at cancer diagnosis of 43.72 years. Sexual function can be negatively affected by concerns about fertility loss, in GC patients.23 We did not find a relation between mean age, age at diagnosis, parity, and education between the two patient groups. We found FSD rate to be 24.1% in our GC survivor cohort; Hasanzadeh et al. found it to be nearly 29% in their cohort of cervical cancer survivors.24 In contrast, in studies conducted in countries with mainly a non-traditional culture, different results were found. For instance, sexual problems in GCs were reported to be 48.4% in a study in the United States, more than 50% in an Australian study, and 58% in a study conducted in Denmark.18,25,26 In many traditional societies with certain persuasions and cultures, the reproductive organs, especially the uterus, are regarded by some women as the essence of their sexuality. The uterus is considered a symbol of femininity, sexuality, and fertility. Therefore, losing their sex organs is perceived by them as losing their femininity. As a result, they avoid talking about their sexual issues. In a study in 2010, it was difficult for many GC survivors to understand their role as a woman; they showed concern about their role as a female in their sexual life.22 Hence, the impact of such mentality on answering the sexual questionnaire, needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results of this study.

In the current study, of the six sexual dysfunction domains, pain was the most common problem in survivors of gynecological cancers (96.55%), followed by problems in sexual arousal (86.21%), vaginal lubrication (72.41%), orgasm (72.41%), satisfaction (65.52%) and desire (55.17%). One of the causes of diminished libido is pain during sexual intercourse, which can result from lack of lubrication. In a study of patients with endometrial and cervical cancer, their lack of libido, sexual excitement, and ability to reach orgasm was attributed to experiencing severe pain during coitus.22 All forms of therapy, especially the combination of surgery and chemotherapy have shown to result in sexual dysfunction in ovarian cancer survivors.27 In a study of 100 sexually active ovarian cancer patients, 80% reported sexual dysfunction due to vaginal dryness.28 Other factors attributing to sexual dysfunction include post coital bleeding, weakness, restricted ability to reach sexual arousal and orgasm, reduced sensitivity of the sexual organs, and fear of cancer transmission through coitus.22

In our study, employed patients had higher rates of overall sexual dysfunction as well as dysfunction in domains of desire, satisfaction, orgasm, and pain, compared to housewives. In addition to the cancer-related factors, stress and responsibility associated with employment are expected to further contribute to sexual dysfunction. Sexual desire declines in a fatigued state and late-night sex are not attractive to a working woman.29

In the present study, we found that the longer the time elapsed since diagnosis of cancer (2 years compared to 1 year), the lower was the rate of overall FSD, along with in areas of sexual arousal, satisfaction, orgasm, and pain. This seems to be the result of patient adaptation to their GC-related issues and treatments over time. A qualitative study on adjustment of sexual activity after management of cervical and endometrial malignancies, reported that many sexual issues improved somewhat over time.30 Sexuality seems to improve over time by integration of psychosocial interventions into patient management. In a study, a significant improvement was noted in sexual health of patients who received up to 12 months of counseling after their cancer treatment; this was evidenced by improved rate of resumption of previous frequency of intercourse in this group (84% vs. 49.2%, p value<0.05).31 A study evaluating sexual function in 173 cervical cancer (lymph node negative) patients who underwent radical hysterectomy (RH), reported severe painful coitus to be an issue in first three months. In first 6 months post- surgery, patients suffered severe orgasmic issues and uncomfortable sexual intercourse but reported dissatisfaction with their sexual life only during the first five weeks post-RH. The study found lack of sexual interest and lubrication to be the long-term sexual issues in the studied population, persisting during the first two years after hysterectomy.32

In our study, postmenopausal women surviving GC, suffered less dysfunction in areas of sexual arousal, satisfaction, and orgasm. This finding suggests that sexual problems are more common in young and non-menopausal patients. A study conducted in UK found older women to be less stressed about their lack of libido than younger women.33 With passage of time, the sexual behavior in middle-aged women is observed to shift from vaginal penetration towards activities such as love and romance-based intimacy.34 It is speculated that with advancing age, patient pays less attention to her sexual function and her old partner becomes less inclined to engage in sexual activity.

We found statistically significant correlation between brachytherapy in GCs and sexual dysfunction. Vaginal stenosis and decreased vaginal lubrication are the possible ways by which brachytherapy reduces sexual satisfaction. A study in 2016 found reduced lubrication to be the cause of increased FDS incidence after brachytherapy.35 Another study, which evaluated 118 women with GCs, reported 97.5% of patients to have suffered from FDS after undergoing surgery and brachytherapy.36

In our study, FSD was significantly more common in patients suffering from DM, specifically in the area of sexual desire. DM and its complications seem to harm sexual desire. A study in 2009 reported diabetic patients to have significantly lower sexual function scores in domains of sexual desire, arousal, vaginal lubrication, orgasm, and overall sexual satisfaction (p value<0.05), and showed duration of DM and age to negatively correlate with all areas of sexual function.37

Study limitationsStudying with more samples and questioning by a psychologist can reduce the errors of the results. To avoid the impact of traditional or cultural mentality on answering the sexual questionnaire in the study, this issue needs to be addressed in detail during the face-to-face interviews. One of the limitations of our study was that participants’ mental health status was not specifically evaluated, and therefore, no potential relationship between underlying mental health and sexual health could be established.

ConclusionIn conclusion, sexual dysfunction in GCs was directly related to employment, brachytherapy and co-existing DM and inversely related to the time elapsed since cancer diagnosis and menopause. Due to the high prevalence of sexual dysfunction in GCs, screening and identification of the disorder followed by appropriate patient education, and provision of solutions, can improve the quality of life in this population. Asking about sexual problems and referral to a specialist should be included in the management process of these patients. Understanding of FDS therapies is essential in setting the best GCs management strategies.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Consent for publicationBy submitting this document, the authors declare their consent for the final accepted version of the manuscript to be considered for publication.

FundingThere is no funding support for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This is extracted from a thesis and the student is one of the authors (Nafiseh Poorzad).