Multifactorial chylomicronemia associated with multiple comorbidities, drugs and habits is much more common than familial chylomicronemia, an autosomal recessive disease that can be considered as “rare disease”. Like the rest of hypertriglyceridemias, chylomicronemias could be classified as primary or monogenic and secondary in which, on the basis of polygenic predisposition, there is concomitant exposure to multiple triggering factors. In this brief revision, we will review its causes and management as well as the keys to its differential diagnosis of the Multifactorial Chylomicronemia.

La quilomicronemia multifactorial asociada a múltiples comorbilidades, fármacos y hábitos de vida es con diferencia mucho más frecuente que la quilomicronemia familiar, enfermedad autosómica recesiva que puede considerarse como “enfermedad rara”. Al igual que el resto de hipertrigliceridemias, las quilomicronemias podrían clasificarse en primarias o monogénicas y secundarias, en las que, sobre una base de predisposición poligénica, hay una exposición concomitante a múltiples factores desencadenantes. En esta breve revisión repasaremos sus causas y manejo, así como las claves para su diagnóstico diferencial.

MCS was initially described1 in a group of patients with marked hypertriglyceridemia, accompanied by abdominal pain, pancreatitis, eruptive xanthomas and mental disorders, which appeared with alcohol consumption–even in small amounts–and poor control of diabetes.

PrevalenceMCS is the most common cause of severe HTG (chylomicronaemia). Although its actual prevalence is unknown, some estimates rate it at 1/600 subjects in the general population.2 In the adult American population in the NHANES study (1999–2004),3 the percentage of subjects with triglyceridaemia > 1000 mg/dL was 0.4%. However, in the most recent Copenhagen study, and taking as a criterion for definitive chylomicronaemia a plasma concentration of triglycerides greater than 10 mmol/L (880 mg/dL), this showed a prevalence of 0.03% in women and 0.14% in men.4

EtiopathogenesisFrom a pathogenic point of view, a polygenic genetic predisposition–one or more variants–with a low impact on the metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL), requires the action of non-genetic precipitating factors that have a negative impact on the plasma clearance of these lipoproteins.5 In other words, the presence of one or more variants–common or rare–associated with exposure to secondary environmental factors, would determine a certain lipoprotein phenotype; i.e. the presence of one or several variants–common or rare–associated with exposure to secondary environmental factors, would determine a certain lipoprotein phenotype, in what we could call, for this and many other situations, exome-exposome interaction. The most frequent precipitating mechanism would be an excess in hepatic production of VLDL6 that would saturate an already compromised lipolysis.7,8 Not all patients with a genetic predisposition for MCS, therefore, will develop this. The study of family segregation has shown that index cases, often previously diagnosed with familial hypertriglyceridemia or combined familial hyperlipidaemia, have much higher levels of triglyceridemia than their first-degree relatives with HTG.9

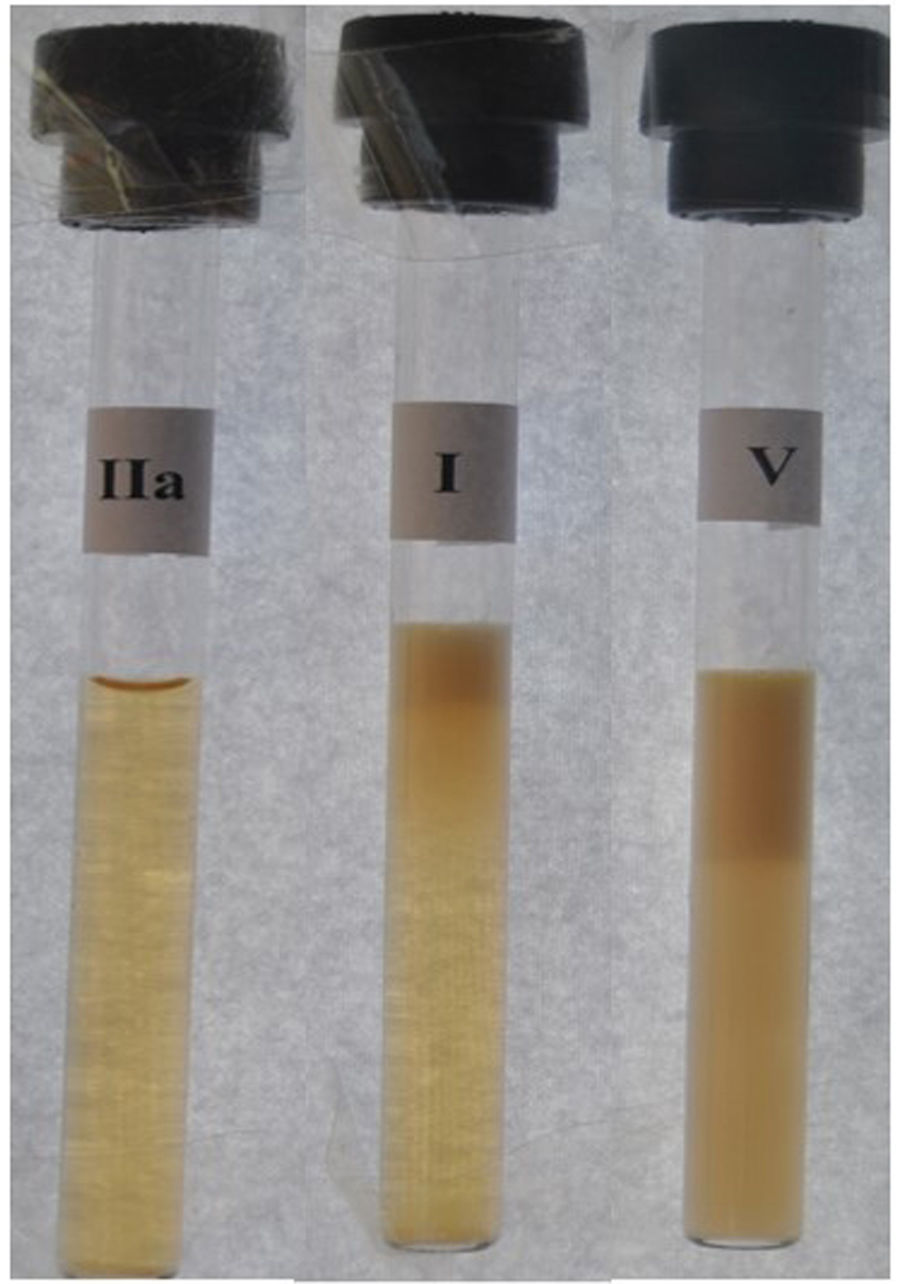

Serum from those with severe HTG has a milky appearance and after a Havel test, which consists of centrifugation at 4 °C and cold storage for more than 12 h, it may show a Fredrickson phenotype I (translucent serum with creamy supernatant) or a phenotype V (cloudy serum with creamy supernatant) when the VLDL level increases, in addition to MC (Fig. 1).10,11 Both phenotypes can occur in FC but phenotype I is classically characteristic, although not necessarily pathognomonic, of FC, while phenotype V usually accompanies MCS in most cases.

Serum phenotypes after refrigeration.

In cases of MCS, refrigerated serum may appear with a milky supernatant (CM) and translucent infranatant or Fredrickson phenotype I, or as a milky supernatant (CM) and turbid infranatant (VLDL) or Fredrickson phenotype V (right). In MCS, only phenotype V (right) is found. This contrasts with pure hypercholesterolemia or phenotype IIa (left).

The associated causes (precipitating or secondary) of MCS6 are listed in Table 1, with the most frequent being alcohol consumption and poorly controlled diabetes. As previously mentioned, this is the summative exome-exposome effect that would give rise, in this case, to a more or less severe triglyceridemia and would explain the clinical heterogeneity, which, in the face of very similar trigger factors, produce very different clinical responses. As an example, two subjects comparable in gender, age and weight with identical alcohol consumption will increase their triglyceride level very differently in quantitative terms depending on the presence or not of heterozygous variants with an impact on their metabolism. In routine clinical practice we can also come across cases with obesity and diabetes with moderate HTG, while others in similar circumstances will express much higher figures, with the added risk of severe chylomicronaemia and lipemic pancreatitis after dietary transgressions. In the near future, the detailed genetic study of these particularly predisposed individuals will enable us to accurately personalise diet, alcohol consumption, drug administration and lifestyle advice, without losing sight of the general health recommendations for the entire population with or without HTG.

Precipitating causes of multifactorial chylomicronaemia syndrome.

| Clinical conditions |

|

| Drugs and Pharmaceuticals |

|

The most serious and characteristic clinical complication of MCS is acute pancreatitis, which is often recurrent. The risk of pancreatitis increases with triglyceride values >1500−2000 mg/dL.12 According to a recent meta-analysis, lipemic pancreatitis associated with MCS involves a longer hospital stay, a higher complication rate and morbidity and mortality than normotriglycaemic pancreatitis.13 A first episode of lipemic pancreatitis should be initially suspected (without knowing the triglyceride count) in the absence of other obvious causes, in children or adolescents and in the presence of laboratory comments indicating milky serum or interference in the determination of various parameters for this reason. Often the first determination of triglycerides in a hospital admission for pancreatitis is delayed till after 48 h of fasting, or a very restrictive diet, which can normalise the number of triglycerides that are slowly cleared by alternative routes. It is desirable to request a lipid profile from the Emergency Unit, or to contact the laboratory to preserve and analyse the initial surplus serum and ideally compare it with the previous historical levels of the patient in question.

It is advisable to ask about previous episodes not only of acute pancreatitis, but also of recurrent abdominal pai which, in many cases, may be milder pancreatitis that these subjects intuitively learn to manage with diet and rest.

One of the differential characteristics of MCS is that triglyceride levels typically oscillate in “mountain peaks”, i.e. values that are often compatible with moderate HTG which, at certain times or periods of exposure to secondary factors, present chylomicronaemia in a timely manner. When these patients are treated pharmacologically and follow diet and lifestyle recommendations, their triglyceride levels drop significantly in most cases, something that would not occur in FC, except in the case of the use of “anti-Apo-CIII” drugs. The only normal or low triglyceride values in the history of patients with FC usually coincide with hospital admissions for pancreatitis or episodes of abdominal pain, which patients treat at home with rest and a practically clear liquid diet.

Differential diagnosis of FC and MCSA key aspect of practical interest in MCS is its differential diagnosis from FC. Although there is no definitive clinical data that enables us to differentiate between the two processes unequivocally, Table 2 includes different variables that may help for this purpose13,14 in order to optimise recommendations on lifestyle habits and the selection of candidates for definitive genetic study and, where appropriate, estimation of LPL activity and mass.

Differential clinical aspects between familial chylomicronaemia syndrome and multifactorial chylomicronaemia syndrome.

| Familial chylomicronaemia | Multifactorial hylomicronaemia | |

|---|---|---|

| Predominant lipoprotein | MC (I) or MC + VLDL (Phenotype V) | MC + VLDL (phenotype V) |

| Appearance | Lipemic | Lipemic |

| of the serum after refrigeration | Milky supernatant and translucent infranatant or milky supernatant and turbid infranatant | Milky supernatant and turbid infranatant |

| History of Pancreatitis | ++++ | ++ |

| Triglyceride values | Consistently very high | Variable, moderately high to very high |

| Obesity | ± | ++++ |

| History of diabetes | + | ++++ |

| Alcohol | – | +++ |

| Combined familial hyperlipidaemia | + | ++++ |

| Response to fibrates | – | + |

A group of experts13 has proposed a practical clinical score for the identification of patients with FC based on eight clinical-biological items, including youthful onset, persistent HTG > 880 mg/dL, history of pancreatitis/abdominal pain, exclusion of secondary causes, or combined familial hyperlipidaemia, and absence of response to fibrates. A score ≥ 10 points in this and a constant Fredrickson phenotype I over time makes the exclusion of MCS very likely, although there are borderline cases in which the diagnosis will not be resolved until the genetic study and, where appropriate, determination of LPL activity and mass. The scenario becomes more complicated, however, when we are dealing with non-homozygous biallelic patients, in the strict sense (double heterozygotes or compound heterozygotes), who have >10 points on the aforementioned score and show serum with phenotype I, given that in the classical concept only true homozygotes for a variant in both alleles (paternal and maternal) would explain the presentation of a disease with recessive inheritance.

In addition to all of the above, it is necessary to bear in mind another cause of chylomicronaemia, which must be included in the differential diagnosis of MCS; little recognised and diagnosed, previously mentioned, and which is of autoimmune origin, due to the presence of anti-LPL15 or anti-GPIHBP116 antibodies. This disorder may present as an unexplained type I phenotype, given the absence of compatible genetic variants but with low or absent LPL activity and mass that, over time, can change to phenotype V hyperlipidaemia, or even be completely corrected in relation to the variation of the changing antibody titre and that make it essential to reclassify the patient in approximately 1:30−40 cases initially diagnosed with FC. It is not uncommon for these patients to suffer–or may suffer during follow-up–from some other concomitant autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, polymyositis or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, among others.

TreatmentThe identification and correction of the precipitating factors of chylomicronaemia constitute the mainstay of treatment in MCS. Unlike FC, in MCS the implementation of improvements in lifestyle and eating habits can considerably reduce or even normalise TGs in plasma. In this sense, the food recommendations made for FC are also valid, although unlike FC, in MCS it is not necessary to supplement with MCT or essential fatty acids, and virgin olive oil can/should be recommended as a priority source of fats.17

In addition, in these cases, concomitant treatment with fibrates and/or omega-3s may help correct HTG.

FundingThis work was funded by an unconditional grant from Sobi, which did not participate in the design of the work or in the drafting of this manuscript.

Information about the supplementThis paper is part of the supplement entitled Severe hypertriglyceridaemia which has been funded by the Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis, with sponsorship from Sobi.

Please cite this article as: Muñiz-Grijalvo O., Blanco Echevarría A., Ariza Corbo M.J., Díaz-Díaz J.L., Quilomicronemia multifactorial: claves para la detección de las formas severas, Clin Investig Arterioscl. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artere.2025.100749