Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. Interleukin 18 (IL-18) is an inflammatory molecule that has been linked to the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the possible relationship between plasma levels of IL-18 and the presence of atherosclerosis evaluated at the carotid level, as well as to analyze the possible modulation by different polymorphisms in a Mediterranean population.

Material and methods746 individuals from the metropolitan area of Valencia were included, recruited over a period of 2 years. Hydrocarbon and lipid metabolism parameters were determined using standard methodology and IL-18 using ELISA. In addition, carotid ultrasound was performed and the genotype of 4 SNPs related to the IL-18 signaling pathway was analyzed.

ResultsPatients with higher plasma levels of IL-18 had other associated cardiovascular risk factors. Elevated IL-18 levels were significantly associated with higher carotid IMT and the presence of atheromatous plaques. The genotype with the A allele of the SNP rs2287037 was associated with a higher prevalence of carotid atheromatous plaque. On the contrary, the genotype with the C allele of the SNP rs2293224 was associated with a lower prevalence of atheromatous plaque.

ConclusionsHigh levels of IL-18 were significantly associated with a higher carotid IMT and the presence of atheromatous plaques, which appear to be influenced by genetic factors, as evidenced by associations between SNPs in the IL-18 receptor gene and the presence of atheroma plaque.

La arteriosclerosis es una enfermedad inflamatoria. La interleucina 18 (IL-18) es una molécula inflamatoria que se ha relacionado con el desarrollo de arteriosclerosis y enfermedad cardiovascular.

ObjetivoEvaluar la posible relación entre los niveles plasmáticos de IL-18 y la presencia de arteriosclerosis evaluada a nivel carotídeo, así como analizar la posible modulación por diferentes polimorfismos en una población mediterránea.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron 746 individuos procedentes del área metropolitana de Valencia, reclutados durante un período de 2 años. Se determinaron parámetros del metabolismo hidrocarbonado y lipídico mediante metodología estándar e IL-18 mediante ELISA. Además, se realizó ecografía carotídea y se analizó el genotipo de 4 SNPs relacionados con la vía de señalización de IL-18.

ResultadosLos pacientes con niveles plasmáticos más elevados de IL-18 presentaron otros factores de riesgo cardiovascular asociados. Los niveles elevados de IL-18 se asociaron de forma significativa con un mayor GIM carotídeo y con la presencia de placas de ateroma. El genotipo con el alelo A del SNP rs2287037 se asoció con mayor prevalencia de placa de ateroma carotídea. Por el contrario, el genotipo con el alelo C del SNP rs2293224 se asoció con una menor prevalencia de placa de ateroma.

ConclusionesLos niveles elevados de IL-18 se asociaron de forma significativa con un mayor GIM carotídeo y con la presencia de placas de ateroma, que parecen estar influenciados por factores genéticos, como lo demuestran las asociaciones entre los SNPs en el gen del receptor de IL-18 y la presencia de placa de ateroma.

Atherosclerosis is an chronic inflammatory disease.1 Studies in experimental animals have demonstrated the importance of different inflammatory mediators in both the onset and development of atherosclerosis.2 Multiple studies in humans have shown the close association between inflammatory markers and the development of cardiovascular disease.3 Furthermore, it has recently been shown that the use of drugs capable of reducing the inflammatory state, without modifying other cardiovascular risk factors, reduces the incidence of cardiovascular disease.4–6

The degree of inflammation, as well as the development of atherosclerosis and subsequent cardiovascular disease, are modulated by both environmental and genetic factors. The regulation of the inflammatory process by genetic factors could explain the great variability in the inflammatory response.7 However, the genetic contribution to both the development of inflammation and atherosclerosis remains a partially unknown factor.

One of the inflammatory molecules that has been linked to the development of atherosclerosis is interleukin 18 (IL-18). In animal models, it has been observed that plasma levels of IL-18 play an important role in both the formation and development of atheromatous plaque, in addition to its stability and severity8 Similar outcomes have also been observed in humans. Different studies have demonstrated the association between IL-18 levels and the development of cardiovascular disease.9–11 Furthermore, some studies have identified the influence of some genetic variations in the genes involved in the IL-18 system on cardiovascular disease and its severity,7,12 although there is less data on Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) located in IL-18 receptor 1 (IL18R1) and IL-18 receptor accessory protein (IL18RAP).However, outcomes are contradictory and their effect on atheromatous plaque has not been evaluated.13,14

Our hypothesis was therefore that plasma levels of IL-18 are associated with the presence of atherosclerosis and genetic variations may exist that could influence the development of atheromatous plaque. The objective of our study was to evaluate the possible relationship between IL-18 plasma levels and the presence of atherosclerosis evaluated at the carotid level, and also to analyse the possible influence of different polymorphisms in the IL18R1 and IL18RAP genes in a Mediterranean population.

Material and methodsSubjectsSeven hundred and forty-six patients from the VALencian CArdiovascular Risk (VALCAR) study were included. This was a cross-sectional study designed to evaluate the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in an urban population, and their association with the presence of atherosclerosis evaluated by carotid ultrasound. The participating individuals were included for two years by consecutive opportunistic sampling from among those who attended different consultations of our health department in a metropolitan area of Valencia.

The exclusion criteria for our study were: patients with chronic inflammatory diseases (both digestive and rheumatic), the presence of plasma levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP)>10 mg/l and having had an infectious or inflammatory episode in the previous 2 weeks.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our centre. All participants provided written consent to participate in the study.

Clinical parametersAn anamnesis was taken for all participants in which special interest was paid to the use of drugs for regular or occasional consumption during the study period, smoking habits (number of cigarettes/day) and alcohol consumption (grams of alcohol/day). A history of cardiovascular disease prior to the date of inclusion in the study was also collected. Blood pressure was determined after 10 min of supine position, using the average value of 3 measurements separated by 5 min.

Anthropometric parametersThe parameters evaluated were: weight in kilograms (kg); height in meters (m); body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2, and waist circumference in centimetres (cm), measured at the midpoint between the anterior superior iliac spine and the lower costal margin, with the subject standing and the arms in an anatomical position. The measurement was obtained with a tape measure graduated in cm.

Biochemical parametersA blood sample was drawn after a 12 h overnight fast. The methodology was similar to that previously described.15 Specifically, plasma levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG) and glucose were determined by enzymatic methods. HDL cholesterol (HDL-c) after precipitation with phosphotungstic acid magnesium chloride. LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated by the Friedewald formula.

Plasma levels of IL-18 were determined by the ELISA technique with “Human IL-18 ELISA Kit” (Medical εt BIologicalLaboratories Co. Ltd.) and quantified by absorbance measurement with the GloMax®-Multi + Detection System apparatus (Promega).

Carotid ultrasoundThe ultrasound was performed using a Siemens Sonoline G40 device, with a high-resolution linear transducer of 8 MHz frequency. The examination was performed with the subjects in the supine position with the head turned at 45° to the opposite side of the side being explored. Three predetermined segments were evaluated on both sides: common carotid (1 cm proximal to the carotid bulb), carotid bulb (1–2 cm) and internal carotid (1 cm distal to the bifurcation).16 Six measurements were made at regular intervals bilaterally in 3 different projections (ACCD: 90–120 and 150°; ACCI: 210, 240 and 270°). All measurements were used for statistical analysis. The intima-media thickness (IMT), defined as the distance between the carotid-intima lumen interface and the media-adventitia interface of the distal wall, was determined in longitudinal sections in the region prior to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery (1 cm). Carotid plaque was considered a focal thickening of more than 50% of the surrounding vessel wall, or a IMT greater than 1.5 mm that protruded into the adjacent lumen.17

All examinations were performed by a single investigator (SM-H) trained in performing carotid ultrasounds and always following the same protocol previously described. The coefficient of variability was studied in 20 subjects, and was 5.2% for the mean IMT of both common carotids.

SNP selection and genotypingGenomic DNA was obtained from blood cells of venous blood, using the Chemagic® system (Chemagen, Baesweiler, Germany). The DNA was quantified and diluted to a final concentration of 100 ng/μl.

The IL-18 receptor SNPs for genotyping were selected based on a conjunction of different parameters: heterozygosity (>10% for the lowest frequency allele) in the Caucasian population, position and spacing along the gene and possible effect functional (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). Four of them were finally selected: rs2270297 and rs2287037 located in IL18R1; rs2293224 and rs7559479 located in IL18RAP. SNPs were genotyped using a SNPlex® assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Statistical methodsQuantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and the qualitative variables as percentages and/or total number. To compare quantitative variables between groups, the Student’s t test and the ANOVA test (2 or more variables, respectively) were used for normally distributed variables. For non-normally distributed variables, the Mann-Whitney test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used (2 or more variables, respectively). To correct confounding factors in some comparison studies, ANCOVA analysis was used. To compare the qualitative variables between groups, the Chi-square test was used, or the Fisher test when the number was under 5. The bivariate correlations between variables were studied with the Pearson test for variables with a normal distribution and Spearman test for variables without normal distribution. To evaluate the factors associated with carotid IMT and the presence of atheromatous plaque, linear and logistic regression analyses were performed, respectively. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than .05. The statistical package SPSS® for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS®, Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Allele and genotype frequencies were calculated for each SNP using SPSS® and y SNPstats (http://bioinfo.iconcologia.net/index.php).18 Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was calculated by the Chi-square test with one degree of freedom using the SNPstat software. Linkage disequilibrium was calculated using the R2 statistic. The association between the polymorphisms and IL-18 levels was analysed using a co-dominant inheritance model using SPSS® and SNPstat. For the comparison of quantitative variables between genotypes, the ANOVA test was used. Age and sex, as 2 potential confounders, were used as covariates. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than .05.

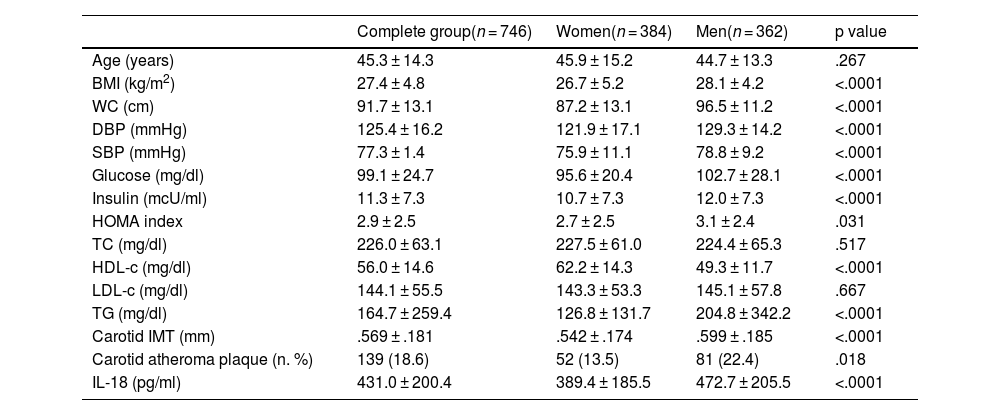

ResultsTable 1 contains the general characteristics of the population studied. Statistically significant differences were found between both genders in BMI; abdominal circumference; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; parameters of carbohydrate metabolism, as well as in HDL-c and plasma triglycerides. Likewise, the levels of IL-18 (472.7 ± 205.5 vs. 389.4 ± 185.5 pg/ml) and carotid IMT (.599 ± .185 vs. .542 ± .174 mm) were significantly higher in men. There was also a higher frequency of atheromatous plaques in men compared to women.

Population characteristics according to gender.

| Complete group(n = 746) | Women(n = 384) | Men(n = 362) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 14.3 | 45.9 ± 15.2 | 44.7 ± 13.3 | .267 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 ± 4.8 | 26.7 ± 5.2 | 28.1 ± 4.2 | <.0001 |

| WC (cm) | 91.7 ± 13.1 | 87.2 ± 13.1 | 96.5 ± 11.2 | <.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 125.4 ± 16.2 | 121.9 ± 17.1 | 129.3 ± 14.2 | <.0001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 77.3 ± 1.4 | 75.9 ± 11.1 | 78.8 ± 9.2 | <.0001 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 99.1 ± 24.7 | 95.6 ± 20.4 | 102.7 ± 28.1 | <.0001 |

| Insulin (mcU/ml) | 11.3 ± 7.3 | 10.7 ± 7.3 | 12.0 ± 7.3 | <.0001 |

| HOMA index | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 2.4 | .031 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 226.0 ± 63.1 | 227.5 ± 61.0 | 224.4 ± 65.3 | .517 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 56.0 ± 14.6 | 62.2 ± 14.3 | 49.3 ± 11.7 | <.0001 |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | 144.1 ± 55.5 | 143.3 ± 53.3 | 145.1 ± 57.8 | .667 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 164.7 ± 259.4 | 126.8 ± 131.7 | 204.8 ± 342.2 | <.0001 |

| Carotid IMT (mm) | .569 ± .181 | .542 ± .174 | .599 ± .185 | <.0001 |

| Carotid atheroma plaque (n. %) | 139 (18.6) | 52 (13.5) | 81 (22.4) | .018 |

| IL-18 (pg/ml) | 431.0 ± 200.4 | 389.4 ± 185.5 | 472.7 ± 205.5 | <.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; p value between women and men.

BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HDL-c: HDL cholesterol; IL-18: interleukin; IMT: intima-media thickness; LDL-c: LDL cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; WC: waist circumference.

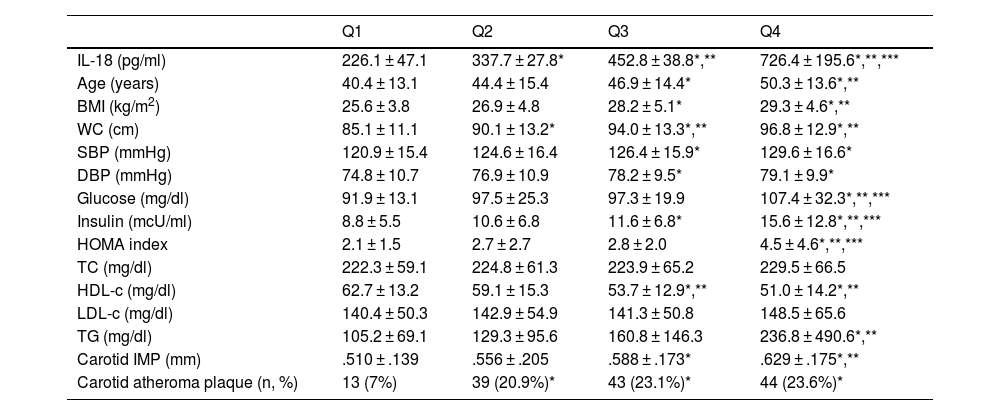

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the population divided according to the quartiles of plasma IL-18 levels. It is observed that as IL-18 levels increase, the levels of parameters associated with the presence of insulin resistance, as well as carotid IMT, increase significantly. The prevalence of atheromatous plaques was significantly lower in the subjects included in the quartile with the lowest levels of IL-18, compared to the other 3, with no significant differences between the other 3 groups.

Populations characteristics based on quartiles of plasma IL-18 levels.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-18 (pg/ml) | 226.1 ± 47.1 | 337.7 ± 27.8* | 452.8 ± 38.8*,** | 726.4 ± 195.6*,**,*** |

| Age (years) | 40.4 ± 13.1 | 44.4 ± 15.4 | 46.9 ± 14.4* | 50.3 ± 13.6*,** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 3.8 | 26.9 ± 4.8 | 28.2 ± 5.1* | 29.3 ± 4.6*,** |

| WC (cm) | 85.1 ± 11.1 | 90.1 ± 13.2* | 94.0 ± 13.3*,** | 96.8 ± 12.9*,** |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120.9 ± 15.4 | 124.6 ± 16.4 | 126.4 ± 15.9* | 129.6 ± 16.6* |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74.8 ± 10.7 | 76.9 ± 10.9 | 78.2 ± 9.5* | 79.1 ± 9.9* |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 91.9 ± 13.1 | 97.5 ± 25.3 | 97.3 ± 19.9 | 107.4 ± 32.3*,**,*** |

| Insulin (mcU/ml) | 8.8 ± 5.5 | 10.6 ± 6.8 | 11.6 ± 6.8* | 15.6 ± 12.8*,**,*** |

| HOMA index | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 4.5 ± 4.6*,**,*** |

| TC (mg/dl) | 222.3 ± 59.1 | 224.8 ± 61.3 | 223.9 ± 65.2 | 229.5 ± 66.5 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 62.7 ± 13.2 | 59.1 ± 15.3 | 53.7 ± 12.9*,** | 51.0 ± 14.2*,** |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | 140.4 ± 50.3 | 142.9 ± 54.9 | 141.3 ± 50.8 | 148.5 ± 65.6 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 105.2 ± 69.1 | 129.3 ± 95.6 | 160.8 ± 146.3 | 236.8 ± 490.6*,** |

| Carotid IMP (mm) | .510 ± .139 | .556 ± .205 | .588 ± .173* | .629 ± .175*,** |

| Carotid atheroma plaque (n, %) | 13 (7%) | 39 (20.9%)* | 43 (23.1%)* | 44 (23.6%)* |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation; p value between women and men.

BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HDL-c: HDL cholesterol; IL-18: interleukin 18; IMT: intima-media thickness; LDL-c: LDL cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; WC: waist circumference.

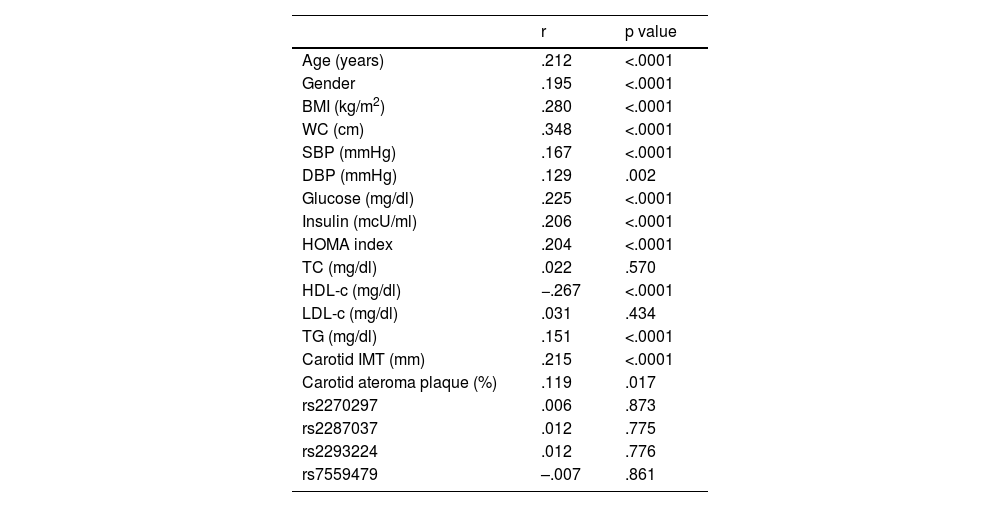

When analysing the association of IL-18 with other parameters (Table 3), significant correlations were observed with the parameters associated with the presence of insulin resistance, as well as with the components included in the definition of metabolic syndrome and, in addition, with carotid IMT and with the presence of atheromatous plaque. There was no significant correlation between the SNPs studied and IL-18 levels.

Correlations between plasma levels of IL-18 and different variables

| r | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | .212 | <.0001 |

| Gender | .195 | <.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | .280 | <.0001 |

| WC (cm) | .348 | <.0001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | .167 | <.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | .129 | .002 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | .225 | <.0001 |

| Insulin (mcU/ml) | .206 | <.0001 |

| HOMA index | .204 | <.0001 |

| TC (mg/dl) | .022 | .570 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | −.267 | <.0001 |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | .031 | .434 |

| TG (mg/dl) | .151 | <.0001 |

| Carotid IMT (mm) | .215 | <.0001 |

| Carotid ateroma plaque (%) | .119 | .017 |

| rs2270297 | .006 | .873 |

| rs2287037 | .012 | .775 |

| rs2293224 | .012 | .776 |

| rs7559479 | –.007 | .861 |

BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HDL-c: HDL cholesterol; IL-18: interleukin 18; IMT: intima-media thickness; LDL-c: LDL cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; WC: waist circumference.

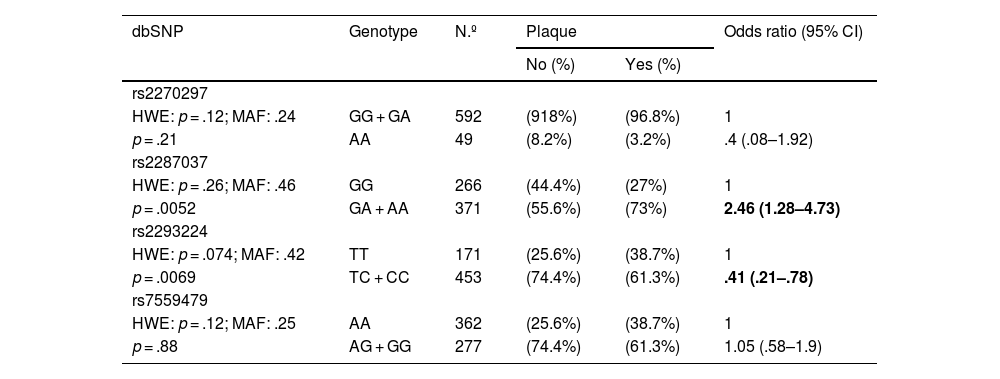

Furthermore, the possible association between the presence of alterations at the carotid level and the polymorphisms analysed was analysed (Table 4). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was maintained for all polymorphisms analysed. Carriers of the minor allele of rs2287037 presented an increased risk of developing atheromatous plaque, while carriers of the minor allele of rs2293224 presented a significant reduction in said risk.

Association between the presence of carotid atheroma plaque and the SNPs of IL-18 adjusted by age and sex.

| dbSNP | Genotype | N.º | Plaque | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Yes (%) | ||||

| rs2270297 | |||||

| HWE: p = .12; MAF: .24 | GG + GA | 592 | (918%) | (96.8%) | 1 |

| p = .21 | AA | 49 | (8.2%) | (3.2%) | .4 (.08–1.92) |

| rs2287037 | |||||

| HWE: p = .26; MAF: .46 | GG | 266 | (44.4%) | (27%) | 1 |

| p = .0052 | GA + AA | 371 | (55.6%) | (73%) | 2.46 (1.28–4.73) |

| rs2293224 | |||||

| HWE: p = .074; MAF: .42 | TT | 171 | (25.6%) | (38.7%) | 1 |

| p = .0069 | TC + CC | 453 | (74.4%) | (61.3%) | .41 (.21–.78) |

| rs7559479 | |||||

| HWE: p = .12; MAF: .25 | AA | 362 | (25.6%) | (38.7%) | 1 |

| p = .88 | AG + GG | 277 | (74.4%) | (61.3%) | 1.05 (.58–1.9) |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF: minor allele frequency; SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism.

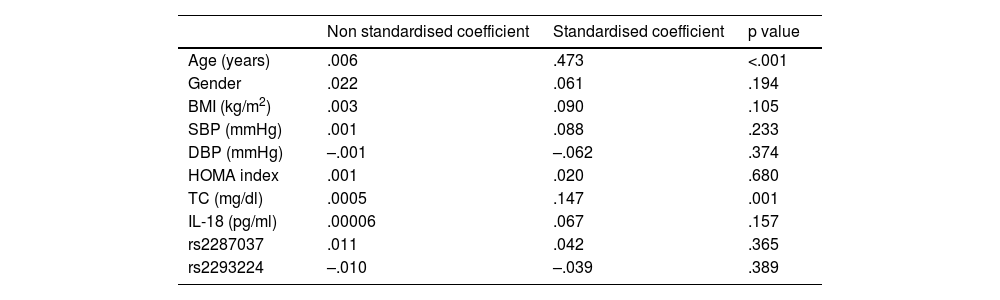

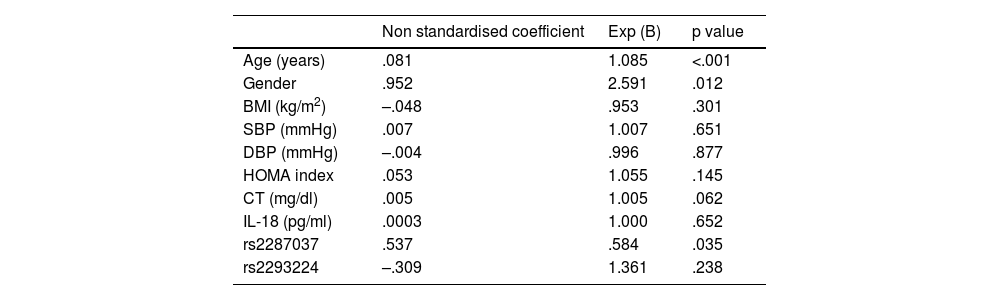

Finally, regression analyses were performed. Using linear regression, the factors associated with the increase in carotid IMT were evaluated, observing a significant correlation only with age and cholesterol levels (Table 5). Using logistic regression, the factors associated with the presence of atheromatous plaque were evaluated, observing a significant association with age, gender and one of the SNPs evaluated, rs2287037 (Table 6).

Regression model evaluating independent determinants of carotid IMT (dependent variable).

| Non standardised coefficient | Standardised coefficient | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | .006 | .473 | <.001 |

| Gender | .022 | .061 | .194 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | .003 | .090 | .105 |

| SBP (mmHg) | .001 | .088 | .233 |

| DBP (mmHg) | –.001 | –.062 | .374 |

| HOMA index | .001 | .020 | .680 |

| TC (mg/dl) | .0005 | .147 | .001 |

| IL-18 (pg/ml) | .00006 | .067 | .157 |

| rs2287037 | .011 | .042 | .365 |

| rs2293224 | –.010 | –.039 | .389 |

BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; IL-18: interleukin 18; IMT: intima-media thickness; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol.

Regression model that evaluates the independent determinants of atheromatous plaque (dependent variable).

| Non standardised coefficient | Exp (B) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | .081 | 1.085 | <.001 |

| Gender | .952 | 2.591 | .012 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | –.048 | .953 | .301 |

| SBP (mmHg) | .007 | 1.007 | .651 |

| DBP (mmHg) | –.004 | .996 | .877 |

| HOMA index | .053 | 1.055 | .145 |

| CT (mg/dl) | .005 | 1.005 | .062 |

| IL-18 (pg/ml) | .0003 | 1.000 | .652 |

| rs2287037 | .537 | .584 | .035 |

| rs2293224 | –.309 | 1.361 | .238 |

BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; IL-18: interleukin 18; IMT: intima-media thickness; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol.

This study demonstrates that patients with higher IL-18 plasma levels have associated cardiovascular risk factors. Furthermore, elevated levels of IL-18 were significantly associated with increased carotid IMT and the presence of atheromatous plaques. This association appears to be influenced by genetic factors, as demonstrated by the associations found between SNPs in the IL-18 receptor gene and the presence of atheromatous plaque.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic disease, the pathogenesis of which involves different inflammatory molecules. Among these, IL-18 is a cytokine that plays an important role in the development of the inflammatory process.19 In fact, it is considered that, together with IL-1β, it is one of the 2 most prominent inflammatory cytokines of the inflammasome that promote the development of atherosclerosis.20 However, in relation to this finding there seem to be contradictory data. Fan et al.21 in a meta-analysis, applying Mendelian randomisation methodology, found no relationship between IL-18 levels and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, knowledge of the role of IL-18, as well as the possible mechanisms involved in the modulation of the atherosclerotic process, is of great interest, particularly because it could be a possible way to help reduce the risk of developing atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.22

In our study, patients with higher levels of IL-18 had higher carotid IMT, as well as a greater association with other cardiovascular risk factors. Furthermore, those with lower levels of IL-18 had a lower proportion of atheroma plaques (Table 2). These findings are in line with previous studies in which it was observed that IL-18 had a proatherogenic role. Thus, plasma levels of IL-18 proved to be a good predictor of both the development of cardiovascular disease and mortality from this cause.11,23 In contrast, animal models deficient in IL-18 have a lower presence of atherosclerosis.24 Furthermore, experimental data indicate that the IL-18 signalling pathway is involved in plaque instability.25,26

However, there is great variability in the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease among patients with elevated levels of IL-18. The presence of different genetic variations could explain this, at least in part.27 Previous studies have shown that polymorphisms in the IL-18 gene are associated with the development of coronary heart disease and its severity,7,12 although there are contradictory data.14,28

L-18 signalling is induced by the binding of this cytokine to a heterodimeric receptor called IL-18R. This is made up of 2 chains, IL-18R1 (with binding function) and IL18RAP (receptor accessory protein, with signal transduction function). The interaction of both IL-18R chains is necessary to induce IL-18 signaling.29,30 In our study we analysed 2 SNPs of IL-18R1 (rs2270297 and rs2287037) and 2 SNPs of IL-18RAP (rs2293224 and rs7559479). We observed that the genotype with the A allele of the SNP rs2287037 of IL-18R1 is associated with a higher prevalence of carotid atheromatous plaque. Due to the location, this SNP could be functional. Furthermore, in the regression analysis, this SNPs was significantly associated with the presence of atheromatous plaque. On the contrary, the genotype with the C allele of the IL-18RAP SNP rs2293224 is associated with a lower prevalence of atheromatous plaque. However, there are no previous studies relating variations in these SNPs with the presence of atherosclerosis.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, it is a cross-sectional study. Therefore, it is not possible to establish causal relationships. Furthermore, the results have not been replicated in another population. Finally, there is no data in this study on the presence of atheromatous plaques at the femoral level. Nor has it been evaluated whether there is an association between the characteristics of the atheroma plaque or the number of affected vascular territories and the levels of IL-18 and the genetic variations studied. However, the findings support the participation of IL-18 in the development of atherosclerosis, as well as its possible regulation.

To conclude, this study carried out in a Mediterranean population suggests that plasma levels of IL-18 are related to other cardiovascular risk factors, especially those related to the presence of insulin resistance. Furthermore, higher levels of IL-18 are related to the presence of atheromatous plaques, and there are genetic variations in the IL-18 receptor gene that could be associated with the development of said atheromatous plaques.

FundingBiomedical Research Networking Centre Consortium (CIBER for its initials in Spanish) CB07/08/0018, Carlos III Health Institute, Ministry of Science and Innovation and European Union (European Regional Development Funds).

AP is the recipient of a Sara Borrell postdoctoral contract from the Carlos III Health Institute (CD22/00012).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Biomedical Research Networking Centre Consortium (CIBER) CB07/08/0018, Carlos III Health Institute, Ministry of Science and Innovation and European Union (European Regional Development Funds).