Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) constitutes a pathology with high mortality. There is currently no screening program implemented in Primary care in Spain.

ObjectivesTo evaluate the usefulness of ultrasound in the detection of AAA in the at-risk population in Primary care. Secondarily, to identify subjects whose vascular risk (VR) should be reclassified and to determine whether AAA is associated with the presence of carotid plaque and other risk factors.

Material and methodsCross-sectional, descriptive, multicenter, national, descriptive study in Primary care. Subjects: A consecutive selection of hypertensive males aged between 65 and 75 who are either smokers or former smokers, or individuals over the age of 50 of both sexes with a family history of AAA.

MeasurementsDiameter of abdominal aorta and iliac arteries; detection of abdominal aortic and carotid atherosclerotic plaque. VR was calculated at the beginning and after testing (SCORE).

Results150 patients were analyzed (age: 68.3 ± 5 years; 89.3% male). Baseline RV was high/very high in 55.3%. AAA was detected in 12 patients (8%; 95%CI: 4–12); aortic ectasia in 13 (8.7%); abdominal aortic plaque in 44% and carotid plaque in 62% of the participants. VR was reclassified in 50% of subjects. The detection of AAA or ectasia was associated with the presence of carotid plaque, current smoking and lipoprotein(a), p < 0.01.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of AAA in patients with VR is high. Ultrasound in Primary care allows detection of AAA and subclinical atherosclerosis and consequently reclassification of the VR, demonstrating its utility in screening for AAA in the at-risk population.

El aneurisma de aorta abdominal (AAA) constituye una patología de alta mortalidad. En España, en Atención Primaria, no hay programa de cribado implantado actualmente.

ObjetivosEvaluar la utilidad de la ecografía en la detección del AAA en población de riesgo en Atención Primaria. Secundariamente, identificar sujetos cuyo riesgo vascular (RV) debe reclasificarse y determinar si el AAA se asocia a la presencia de placa carotídea y otros factores de riesgo.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo transversal, multicéntrico nacional en Atención Primaria.

SujetosSelección consecutiva de varones hipertensos entre 65-75 años, fumadores o exfumadores; o mayores de 50 años de ambos sexos con antecedentes familiares de AAA. Mediciones: Diámetro de aorta abdominal y arterías ilíacas; detección de placa aterosclerótica aórtica abdominal y carotídea. Se calculó el RV inicialmente y tras las pruebas (SCORE).

ResultadosSe analizaron 150 pacientes (edad: 68,3 ± 5 años; 89,3% varones). El RV inicial era alto/muy alto en el 55,3%. Se detectó AAA en 12 pacientes (8%; IC95%:4-12); ectasia aórtica en 13 (8,7%); placa aórtica abdominal en el 44% y placa carotídea en el 62% de los participantes. Se reclasificó el RV en el 50% de los sujetos. La detección de AAA o ectasia se asociaron a la presencia de placa carotídea, tabaquismo actual y lipoproteína(a), p < 0,01.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de AAA en pacientes con RV es elevada. La ecografía en Atención Primaria permite detectar AAA y aterosclerosis subclínica y consecuentemente reclasificar el RV, demostrando su utilidad en el cribado de AAA en población de riesgo.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is characterised by dilatation of the abdominal aorta, with a diameter greater than or equal to 3 cm. More than 90% are located in the distal portion, below the renal arteries. It is a serious condition, with a prevalence in people over 65 years of age of between 5%–8% in men and 2% in women. It is closely related to atherosclerosis, with similar risk profiles; it is the result of a multifactorial process leading to the destruction of the connective tissue of the aortic wall. Smoking is the major risk factor, other influencing factors are age, hypertension, and family history of AAA. Its natural history is distinguished by an initial asymptomatic phase of prolonged duration. Thus, 70%–75% of AAAs are asymptomatic, detected incidentally on clinical examination or imaging tests performed for other reasons.1–6 Rupture of the AAA is the most serious complication, and is directly related to its size and growth rate. Rupture is always treated surgically because all patients would otherwise die of haemorrhagic shock; surgical mortality of ruptured aneurysms ranges from 50%–80%. The current recommendations are early detection, growth monitoring, and scheduled surgical repair for a diameter greater than 5.5 cm in men, 5 cm in women, or an increase in size greater than .5 cm in six months.1–3,7,8

Abdominal ultrasound is the method of choice for both diagnosis and follow-up of AAA; it is considered a good screening tool in the at-risk population, with a diagnostic sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 100%. Ultrasound, as well as identifying AAA, detects aortic ectasia (diameter between 25–29.9 mm) and subclinical atherosclerosis (carotid or femoral plaque burden) helping to improve vascular risk (VR) classification.5,9–11 In this context, the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) study observed that subjects with carotid plaque had a 31% increased risk of developing incident clinical AAA, suggesting that carotid plaque may be a risk marker for AAA formation.12 Similarly, some studies consider ectasia a marker for VR and AAA.13–16

Systematic screening for AAA with ultrasound would be indicated in the population over 65 years of age, male, and with a history of smoking or active smokers, level of evidence IA. It is also indicated in men and women over 50 years of age with a first-degree family history of AAA.2,3,7,8,17,18 Some countries, such as England, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, and the USA, have implemented screening programmes in the at-risk population that have proven effective and cost-effective.3,5,17,19,20

In Spain, no screening programme has yet been implemented in primary care. Screening studies have been conducted, some limited to a single centre,21–23 some multicentre studies undertaken in the hospital setting, and some that are not recent.14,24–26

The aim of this study was to assess ultrasound in the detection of AAA in the at-risk population in primary care. Secondarily, we aimed to identify subjects whose VR needs to be reclassified and to determine whether AAA is associated with the presence of carotid plaque and other risk factors.

Material and methodsDesignThis was a nationwide, non-randomised, descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre, descriptive, nationwide study conducted in primary care (six health centres in five autonomous communities). The investigators were general practitioners, with availability of ultrasound in their centre and experience in its use.

SubjectsA consecutive, non-probabilistic selection was made of patients seen in consultation (over 12 months: June 2022–June 2023) who met the following inclusion criteria: hypertensive males aged 65–75 years, smokers or ex-smokers, or over 50 years of both sexes with a first-degree family history of AAA, in a situation of primary or secondary prevention and who signed the informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were people previously diagnosed with AAA, with moderate to severe cognitive impairment, with clinical conditions that, according to medical criteria, made their inclusion inadvisable and who refused to participate. An approximate sample of 156 was estimated for an expected prevalence of AAA of 8% in at-risk subjects, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), precision of 4.5%, and loss rate of 10%.

Data collectionInformation was collected from medical history, history taking, physical examination, laboratory tests, and abdominal vascular and carotid ultrasound. The data were entered into a centralised, coded, and error-filtered electronic database created on the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) platform, developed by Vanderbilt University, USA.

The recommendations of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA) on cardiovascular risk standards were followed to define diagnoses and variables.27

Main variables or resultAbdominal ultrasound was used to determine the diameter of the abdominal aorta, the iliac arteries, and the existence of atheromatous plaque in any of the sections. The examination was performed in the supine position and using a low frequency convex probe, between 3.5 and 5 MHz. Measurements were taken in the proximal, medial, and distal aorta at the level of the bifurcation at the iliacs. The maximum diameter in cross section from the outermost walls of the aorta was recorded. AAA was considered with an abdominal aorta diameter ≥3 cm or iliac aorta diameter ≥1.5 cm; and aortic ectasia with an aortic diameter of 25–29.9 mm.2,3

Ultrasound was performed with a 7-10 MHz broadband linear transducer to assess the existence of carotid plaque with the patient in the supine decubitus position and the cervical region extended. Both carotid arteries were scanned for the presence of plaques in the common carotid, the carotid bulb, and the internal and external arteries, at least at three angles of incidence (anterior, lateral, and posterior),2,3 a focal thickening of the intima-media thickness (IMT) ≥ 1 mm was considered a plaque.27

Independent variablesSociodemographic variables were age and sex, while clinical variables were first-degree family history of AAA or early cardiovascular disease (CVD), current or past smoking (quantified in packs/year), physical activity (using the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans questionnaire), body mass index (BMI), abdominal circumference, presence of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, left ventricular hypertrophy, or CVD (ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, or kidney disease).

Laboratory testsRoutine blood work was performed, including a complete lipid profile and inclusion of potential serological biomarkers: microalbuminuria (albumin/creatinine ratio: mg/g), glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula (GFR: mL/min/1.73 m2), glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), non-HDL-cholesterol (non-HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), lipoprotein (a) (Lp[a]), D-dimer and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Atherogenic dyslipidaemia was considered at TG values ≥ 150 mg/dL and low HDL-C (< 40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women). Each patient’s VR was calculated at baseline and after testing, using SCORE (Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation) tables for low-risk countries and European guidelines.27,28

A digital copy of the coded ultrasound images was kept for review for the duration of the study. Participating general practitioners had accredited training in vascular ultrasound. In addition, a pre-test was performed with a sample of subjects to assess the degree of agreement between the measurements taken by the investigators (using the intraclass correlation coefficient), with excellent agreement (.93; 95% CI .7–.9).

Diagnostic confirmationDetected and borderline cases were consulted with the team radiologist, who performed an ultrasound scan in the radiodiagnostic service. Confirmed AAA cases were referred to the referral vascular surgery department for evaluation and follow-up.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis was performed for qualitative variables (absolute frequencies and percentages) and quantitative variables (means, standard deviations [SD], and ranges). Quantitative variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro Wilks test and homogeneity of variances using Levene's test. A bivariate analysis was then performed: X2 test to contrast proportions (or Fisher's F, depending on the conditions); Student's t-test (or Mann-Whitney U, its non-parametric equivalent) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the comparison of means. Finally, a multivariate analysis (logistic regression, Wald stepwise method) was fitted including in the model the variables with p < .10 in the bivariate analysis and those of clinical relevance according to the investigators, taking as dependent variable the presence or absence of AAA and aortic ectasia (SPSS 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA.).

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of Malaga (act 12/2021) and the local RECs. The recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines were followed. The referral radiodiagnostic and vascular surgery departments were informed of the study and their collaboration was requested. All participants signed the informed consent form.

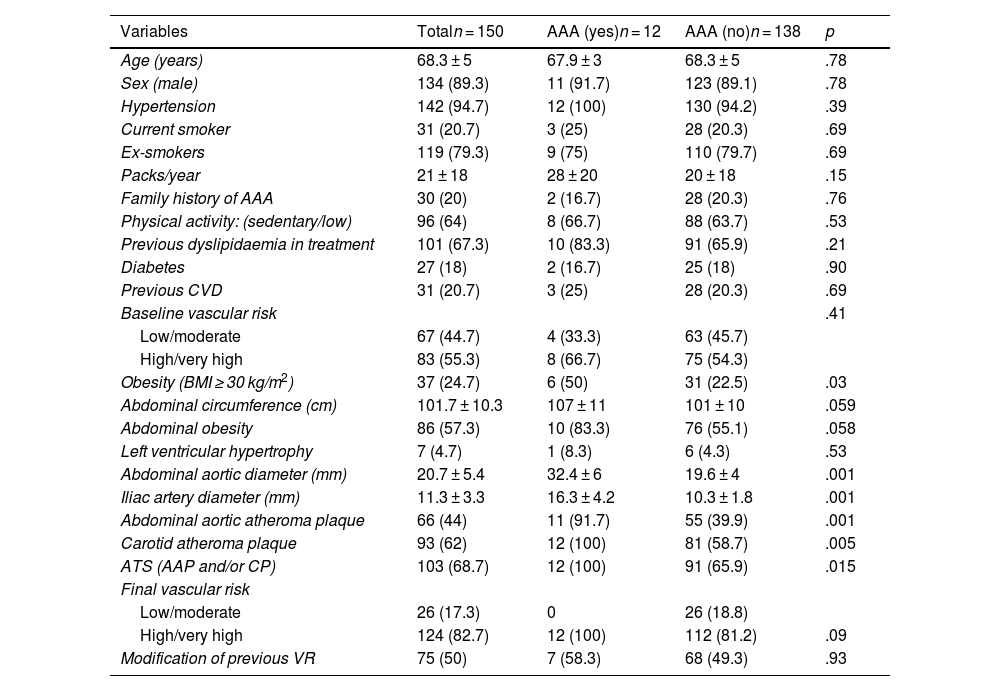

ResultsOf the 157 patients selected, 150 completed the ultrasound study (age: 68.3 ± 5 years; 89.3% male). A total of 94.7% were hypertensive, 20.7% were active smokers, and the rest were ex-smokers. They had a family history of AAA 20%. They had previous dyslipidaemia 67.3% (79% treated with statin monotherapy). Previous CVD was present in 20.7% and the initial VR was high/very high in 55.3% of the subjects (Table 1).

Characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | Totaln = 150 | AAA (yes)n = 12 | AAA (no)n = 138 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.3 ± 5 | 67.9 ± 3 | 68.3 ± 5 | .78 |

| Sex (male) | 134 (89.3) | 11 (91.7) | 123 (89.1) | .78 |

| Hypertension | 142 (94.7) | 12 (100) | 130 (94.2) | .39 |

| Current smoker | 31 (20.7) | 3 (25) | 28 (20.3) | .69 |

| Ex-smokers | 119 (79.3) | 9 (75) | 110 (79.7) | .69 |

| Packs/year | 21 ± 18 | 28 ± 20 | 20 ± 18 | .15 |

| Family history of AAA | 30 (20) | 2 (16.7) | 28 (20.3) | .76 |

| Physical activity: (sedentary/low) | 96 (64) | 8 (66.7) | 88 (63.7) | .53 |

| Previous dyslipidaemia in treatment | 101 (67.3) | 10 (83.3) | 91 (65.9) | .21 |

| Diabetes | 27 (18) | 2 (16.7) | 25 (18) | .90 |

| Previous CVD | 31 (20.7) | 3 (25) | 28 (20.3) | .69 |

| Baseline vascular risk | .41 | |||

| Low/moderate | 67 (44.7) | 4 (33.3) | 63 (45.7) | |

| High/very high | 83 (55.3) | 8 (66.7) | 75 (54.3) | |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 37 (24.7) | 6 (50) | 31 (22.5) | .03 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 101.7 ± 10.3 | 107 ± 11 | 101 ± 10 | .059 |

| Abdominal obesity | 86 (57.3) | 10 (83.3) | 76 (55.1) | .058 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 7 (4.7) | 1 (8.3) | 6 (4.3) | .53 |

| Abdominal aortic diameter (mm) | 20.7 ± 5.4 | 32.4 ± 6 | 19.6 ± 4 | .001 |

| Iliac artery diameter (mm) | 11.3 ± 3.3 | 16.3 ± 4.2 | 10.3 ± 1.8 | .001 |

| Abdominal aortic atheroma plaque | 66 (44) | 11 (91.7) | 55 (39.9) | .001 |

| Carotid atheroma plaque | 93 (62) | 12 (100) | 81 (58.7) | .005 |

| ATS (AAP and/or CP) | 103 (68.7) | 12 (100) | 91 (65.9) | .015 |

| Final vascular risk | ||||

| Low/moderate | 26 (17.3) | 0 | 26 (18.8) | |

| High/very high | 124 (82.7) | 12 (100) | 112 (81.2) | .09 |

| Modification of previous VR | 75 (50) | 7 (58.3) | 68 (49.3) | .93 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

AAA: abdominal aortic aneurysm; AAP: abdominal aortic plaque; ATS: atherosclerosis; BMI: body mass index; CP: carotid plaque; CVD: cardiovascular disease; VR: vascular risk.

After ultrasound, AAA was detected in 12 patients (8%; 95% CI 4–12), with a maximum diameter of 4.6 cm, aortic ectasia in 13 (8.7%; 95% CI 4–13), abdominal aortic plaque in 66 cases (44%; 95% CI 36–52), and carotid plaque in 93 subjects (62%; 95% CI 54–70).

In the asymptomatic patients with no history of previous CVD atherosclerotic plaques were identified in the abdominal aorta and/or carotid arteries in 63% (subclinical atherosclerosis). The final VR was high/very high in 82.7%. These findings led to reclassification of the previous VR and revision of the LDL-C target in 50% of the study subjects (95% CI 42–58).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the subjects overall and according to the presence or absence of AAA. Of the 12 patients with AAA, 11 (91.7%) were male and 83.3% had abdominal obesity. Of the cases, 66.7% had initial high/very high VR and 25% had previous CVD. Of the 30 individuals with a family history, two (6.7%) were identified with AAA.

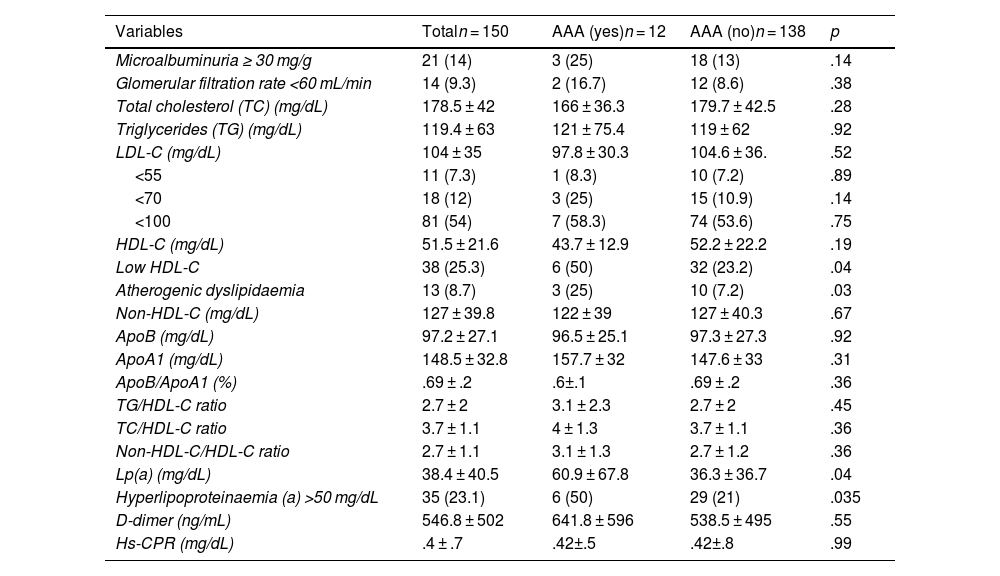

All the subjects with AAA had carotid atheromatous plaques (p < .01), resulting in a prevalence of AAA of 12.8% among all patients with carotid plaque. Furthermore, those with AAA had a higher prevalence of dyslipidaemia, microalbuminuria, atherogenic dyslipidaemia, hyperlipoproteinaemia(a), and low HDL-C, compared with the patients without the condition. All other measurements (lipid profile, lipid indices, ApoB, non-HDL-C, D-dimer, hs-CRP) were similar in both groups (Tables 1 and 2).

analytical data overall and according to the presence or absence of AAA.

| Variables | Totaln = 150 | AAA (yes)n = 12 | AAA (no)n = 138 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microalbuminuria ≥ 30 mg/g | 21 (14) | 3 (25) | 18 (13) | .14 |

| Glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min | 14 (9.3) | 2 (16.7) | 12 (8.6) | .38 |

| Total cholesterol (TC) (mg/dL) | 178.5 ± 42 | 166 ± 36.3 | 179.7 ± 42.5 | .28 |

| Triglycerides (TG) (mg/dL) | 119.4 ± 63 | 121 ± 75.4 | 119 ± 62 | .92 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 104 ± 35 | 97.8 ± 30.3 | 104.6 ± 36. | .52 |

| <55 | 11 (7.3) | 1 (8.3) | 10 (7.2) | .89 |

| <70 | 18 (12) | 3 (25) | 15 (10.9) | .14 |

| <100 | 81 (54) | 7 (58.3) | 74 (53.6) | .75 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 51.5 ± 21.6 | 43.7 ± 12.9 | 52.2 ± 22.2 | .19 |

| Low HDL-C | 38 (25.3) | 6 (50) | 32 (23.2) | .04 |

| Atherogenic dyslipidaemia | 13 (8.7) | 3 (25) | 10 (7.2) | .03 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) | 127 ± 39.8 | 122 ± 39 | 127 ± 40.3 | .67 |

| ApoB (mg/dL) | 97.2 ± 27.1 | 96.5 ± 25.1 | 97.3 ± 27.3 | .92 |

| ApoA1 (mg/dL) | 148.5 ± 32.8 | 157.7 ± 32 | 147.6 ± 33 | .31 |

| ApoB/ApoA1 (%) | .69 ± .2 | .6±.1 | .69 ± .2 | .36 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 2.7 ± 2 | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 2.7 ± 2 | .45 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4 ± 1.3 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | .36 |

| Non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratio | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | .36 |

| Lp(a) (mg/dL) | 38.4 ± 40.5 | 60.9 ± 67.8 | 36.3 ± 36.7 | .04 |

| Hyperlipoproteinaemia (a) >50 mg/dL | 35 (23.1) | 6 (50) | 29 (21) | .035 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 546.8 ± 502 | 641.8 ± 596 | 538.5 ± 495 | .55 |

| Hs-CPR (mg/dL) | .4 ± .7 | .42±.5 | .42±.8 | .99 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

AAA: abdominal aortic aneurysm; ApoA1: apolipoprotein A1; ApoB: apolipoprotein B; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a): lipoprotein (a); non-HDL-C: non-HDL cholesterol.

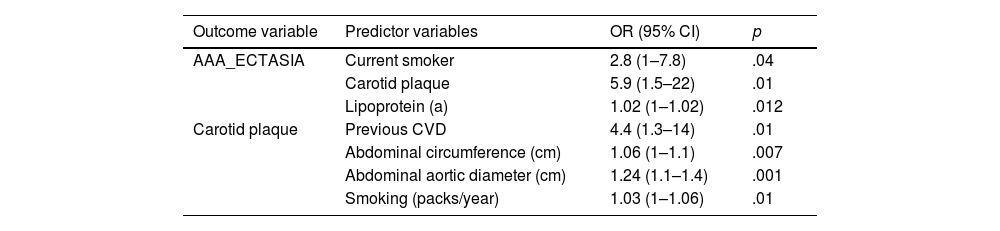

In the multivariate analysis (Table 3), the detection of AAA or ectasia was significantly associated with being a current smoker, having carotid plaque and increased Lp(a). Other related variables did not reach statistical significance. However, the detection of carotid plaque was significantly associated with previous CVD, smoking intensity (packs/year), abdominal obesity, and abdominal aortic diameter, p < .01.

Multivariate analysis by logistic regression.

| Outcome variable | Predictor variables | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA_ECTASIA | Current smoker | 2.8 (1–7.8) | .04 |

| Carotid plaque | 5.9 (1.5–22) | .01 | |

| Lipoprotein (a) | 1.02 (1–1.02) | .012 | |

| Carotid plaque | Previous CVD | 4.4 (1.3–14) | .01 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 1.06 (1–1.1) | .007 | |

| Abdominal aortic diameter (cm) | 1.24 (1.1–1.4) | .001 | |

| Smoking (packs/year) | 1.03 (1–1.06) | .01 |

AAA_ECTASIA: abdominal aortic aneurysm and/or ectasia; CVD: cardiovascular disease; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

In terms of the degree of control of CV factors, it was observed that of 83 patients with high/very high baseline VR, 79.5% had good BP control in the last 6 months; 57.8% had LDL-C <100 mg/dL and only 15.7% LDL-C <70 mg/dL. In addition, 25% were still smoking.

DiscussionOur results show that in at-risk patients (men aged 65–75 years, hypertensive, and current or past smokers, or with a family history of AAA) opportunistic screening by clinical ultrasound performed by general practitioners identified 12 with AAA (8%) and 13 with ectatic abdominal aorta (8.7%). In addition, a high prevalence of atherosclerotic plaques (carotid and abdominal aorta) was detected in the overall sample, leading to reclassification of the previous VR and revision of the LDL-C target in 50% of them.

The characteristics of patients with AAA or ectasia were similar, as observed by Cornejo et al.14 This is consistent with some population-based studies suggesting that ectasia may be considered a risk marker for developing AAA.13,15,20

All the patients with AAA had carotid atheromatous plaques. These data are in line with Torres et al.5 and Yao et al.,12 who found an association between the presence of carotid plaque and AAA. Along these lines, our results suggest, in agreement with Yao et al.,12 that the detection of carotid plaque could be useful as a risk marker for AAA screening, in addition to the already known risk factors.

In the laboratory tests, a relationship was found between the presence of AAA and Lp(a), atherogenic dyslipidaemia, and lower HDL-C levels, in line with other authors.5,29 It should be noted that in half the cases of AAA, we observed hyperlipoproteinaemia(a), with a statistically significant association that was maintained in the multivariate analysis. Elevated Lp(a) is one of the most common lipid abnormalities and is considered an independent hereditary risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD and AAA, which does not change with treatment to lower LDL cholesterol levels. It is recommended that it be measured at least once in a lifetime, as its levels are very stable.5,11,27 A recent meta-analysis found an association between elevated Lp(a) and AAA, but more studies are needed to assess its usefulness in the early detection of AAA.29

The prevalence of AAA in our sample (8%) was high, although similar to other studies conducted in our country in patients with VR in angiology, cardiology, and internal medicine consultations.14,24,30 In other studies conducted in primary care, prevalences were somewhat lower than in the present analysis, ranging from 3.3% to 5.8%.23,25,31 These differences are probably due to the type of screening and the risk factors considered in the inclusion criteria; our screening was very selective, targeting the at-risk population recommended in the guidelines.7,8,18 Each screening strategy will be feasible according to prevalence and available resources, being more effective in populations with a prevalence of AAA greater than 4% in reducing associated mortality.17,19,24

Detection of atheromatous plaques in carotid arteries by ultrasound is currently suggested as a new paradigm in cardiovascular prediction (recommendation IIa); when significant, they automatically mean the patient is reclassified as at very high VR, as they have a strong predictive value for both stroke and myocardial infarction regardless of traditional VR factors.10,11,27 The prevalence of carotid plaque in our study (62%) is somewhat higher than those found in some population-based screening studies, which range between 25% and 47%.12,32,33 These differences could be due, as already mentioned, to the different types of screening (population vs. selective, and age of the target population, among others).

Notably, in this study, subclinical atherosclerosis was detected in 75 (63%) of the patients without previous CVD. Identification of these subjects reclassified their VR level and led to intensified preventive measures.11 This is of great importance because asymptomatic individuals with carotid artery atherosclerosis have been shown to have a high risk of coronary heart disease and an increased risk of AAA.12 These results are similar to those reported in other population-based studies34 and in primary care.35

The prevalence of other VR factors (which were not part of the inclusion criteria of this study) is similar to those described by other authors,36–38 with insignificant differences.

The degree of lipid control in patients at high and very high risk is worth mentioning, where our results can be improved; however, they are similar to those found in the Dyslipidaemia Observatory Study,39 and other national studies,40 with a degree of compliance that is still far from that recommended by the guidelines. Although this was not the aim of the present study, it reflects a reality that requires more detailed research, with ample room for improvement.

Limitations of the studyAs this is a cross-sectional study, it will not be possible to establish causal relationships. On the other hand, the patients who attended the consultations of the participating doctors were included through non-probabilistic screening and the results cannot be extrapolated to the general population. However, we consider that, despite not being a random sample, it was sufficient to meet the main objective of the study.

In terms of the ultrasound measurements, there may be errors due to limitations of the technique itself and interobserver variability. To control these errors, the participating doctors were trained beforehand and the degree of concordance between the measurements made by the researchers and the referral expert was assessed.

For the initial assessment of VR, we used the SCORE system instead of SCORE2/SCORE2-OP because when the study was designed it was the recommended system; this also allowed us to compare VR assessment with other published articles that primarily used the same system. This does not affect the main objective, nor the reclassification of the patient to a higher risk level after clinical ultrasound and the detection of AAA or atherosclerosis.

Another limitation of the study is that the characteristics of the plaques were not considered; assessment of plaque echogenicity improves CVD risk prediction. However, this was not a stated objective and would have added to the complexity of the research study.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of AAA in patients with high VR is high. Non-invasive diagnostic techniques, such as ultrasound performed in primary care, detect AAA in asymptomatic subjects, which shows how useful they are in screening the at-risk population. The detection of carotid plaque in all cases of AAA confirms a significant association between the two; this could be useful as a risk marker for screening for this disease. Detection of AAA and subclinical atherosclerosis allows patients' VR to be reclassified to optimise their treatment. Based on these results, and although effectiveness studies with a larger sample size are needed, AAA screening programmes overseen by general practitioners in the at-risk population would be beneficial.

FundingThis study was partially funded by a FEA/SEA 2022 grant for Primary Care Research and an unconditional grant from the Naut de Aran Town Council (Lleida). There was no participation of any kind from these institutions.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the patients and all participants, the SEMERGEN Working Group on Vasculopathies, and the following collaborating physicians: J.M. Boxó Cifuentes, E. Cámara Sola, S. Martín Izquierdo, M.L. Moya Rodríguez, M.P. Navarro Gallardo, I. Quiñones Begines, and M.D. Rodríguez Santos.

We extend special thanks to Andrés Cobos Díaz (Laboratorio Análisis Clínicos, Hospital Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga), Andrés González and his collaborators (bioinformatician, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga), and Fernando Javier Sánchez Lora (director of the Unidad de Gestión Clínica de Medicina Interna, Hospital Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga), for their invaluable help, without which this work would not have been possible.

We thank the Town Council of Naut Aran (Lleida) for their unconditional collaboration.

Aguado Castaño, Ana Carlota. Centro de Salud Parque Lo Morant, Alicante.

Aicart Bort, María Dolores. Médica Jubilada.

Babiano Fernández, Miguel Ángel. C. de Salud Argamasilla de Calatrava, Ciudad Real.

Bonany Pagès, Maria Antònia. Medicina privada, Girona.

Caballer Rodilla, Julia. Centro de Salud Algete, Madrid.

Cabrera Ferriols, María Ángeles. Centro de Salud San Vicente del Raspeig I, Alicante.

Carrasco Carrasco, Eduardo. Centro de Salud de Abarán, Murcia.

Frías Vargas, Manuel. Centro de Salud San Andrés, Madrid.

Fuertes Domínguez, Diana. Centro de Salud Cervera de Pisuerga, Palencia.

García Lerín, Aurora. Centro de Salud, Almendrales, Madrid.

García Vallejo, Olga. Centro de Salud Almendrales, Madrid

Gil Gil, Inés. Centro de Salud Vielha, Lleida.

Lahera García, Ana. Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid.

López Téllez, Antonio. Centro de Salud Puerta Blanca, Málaga.

Lozano Bouzon, Víctor Manuel. Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid.

Padilla Sáez, Alicia. Centro de Salud San Vicente del Raspeig I, Alicante.

Parra Valderrama, Adriana. UGC La Lobilla. Estepona, Málaga.

Peiró Morant, Juan. Centro de Salud Ponent, Islas Baleares.

Perdomo García, Frank J. Urgencias, Hospital La Paz, Madrid.

Pérez Vázquez, Estrella. Centro de Salud Vielha, Lleida.

Piera Carbonell, Ana. Centro de Salud la Corredoria. Área IV, SESPA, Oviedo.

Pietrosanto, Teresa. Centro de Salud San Vicente del Raspeig I, Alicante.

Ramírez Torres, José Manuel. Centro de Salud Puerta Blanca, Málaga.

Ruíz Calzada, Marta. Centro de Salud Simancas, Arroyo de la Encomienda, Valladolid.

Vázquez Gómez, Natividad. Centro de Salud Auxiliar Moncófar, Castellón.