Imaging is instrumental in diagnosing and directing the management of atherosclerosis. In 1958 the first diagnostic coronary angiography (CA) was performed, and since then further development has led to new methods such as coronary CT angiography (CTA), optical coherence tomography (OCT), positron tomography (PET), and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Currently, CA remains powerful for visualizing coronary arteries; however, recent studies show the benefits of using other non-invasive techniques. This review identifies optimum imaging techniques for diagnosing and monitoring plaque stability. This becomes even direr now, given the rapidly rising incidence of atherosclerosis in society today. Many acute coronary events, including acute myocardial infarctions and sudden deaths, are attributable to plaque rupture. Although fatal, these events can be preventable. We discuss the factors affecting plaque integrity, such as increased inflammation, medications like statins, and increased lipid content. Some of these precipitating factors are identifiable through imaging. However, we also highlight significant complications arising in some modalities; in CA this can include ventricular arrhythmia and even death. Extending this, we elucidated from the literature that risk can also vary based on the location of arteries and their plaques. Promisingly, there are less invasive methods being trialled for assessing plaque stability, such as Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMR), which is already in use for other cardiac diseases like cardiomyopathies. Therefore, future research focusing on using imaging modalities in conjunction may be sensible, to bridge between the effectiveness of modalities, at the expense of increased complications, and vice versa.

La imagen tiene un carácter instrumental para diagnosticar y dirigir el manejo de la aterosclerosis. En 1958 se realizó la primera angiografía coronaria (AC) diagnóstica, y desde entonces el resto de desarrollos ha originado métodos nuevos tales como la angiografía coronaria por TC (ACTC), la tomografía de coherencia óptica (TCO), la tomografía por emisión de positrones (PET) y el ultrasonido intravascular (IVUS). Actualmente, la AC sigue siendo una herramienta potente a la hora de visualizar las arterias coronarias; sin embargo, los estudios recientes muestran los beneficios del uso de otras técnicas no invasivas. Esta revisión identifica las técnicas de imagen óptimas para el diagnóstico y la monitorización de la estabilidad de la placa. Esto se vuelve cada vez más acuciante, dada la incidencia rápidamente creciente de la aterosclerosis en la sociedad actual. Muchos episodios coronarios agudos, incluyendo infartos de miocardio agudos y muertes súbitas, son atribuibles a la rotura de la placa. Aunque son fatales, dichos episodios pueden prevenirse. Debatimos los factores que afectan a la integridad de la placa, tales como el incremento de la inflamación, los fármacos tales como las estatinas, y el incremento del contenido lipídico. Algunos de estos factores precipitantes son identificables mediante imagen. Sin embargo, también subrayamos las complicaciones significativas que surgen de las diversas modalidades. En la AC esto puede incluir la arritmia ventricular e incluso la muerte. Ampliando esta cuestión, pudimos deducir de la literatura que el riesgo puede también variar, sobre la base de la localización de las arterias y sus placas. De manera prometedora, se están probando métodos menos invasivos para valorar la estabilidad de la placa, tales como la imagen de resonancia magnética cardiaca (IRMC), que ya se utiliza para otras enfermedades cardiacas tales como cardiomiopatías. Por tanto, la investigación futura centrada en el uso de modalidades de imagen conjuntas debe ser sensible, para servir de puente entre la efectividad de las modalidades, a costa del incremento de las complicaciones, y viceversa.

In cardiac disease, imaging is vital for diagnosis and as of recent years, intervention for treatment. In 1958 the first diagnostic coronary angiography was performed, and since then further development has led to new diagnostic techniques such as coronary CT angiography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and positron tomography (PET).1 Currently, coronary angiography remains popular for visualizing coronary arteries; however, recent studies show the benefits of using other non-invasive techniques.2 Using imaging techniques for monitoring and diagnosis is important as studies have shown that most acute coronary events, including acute myocardial infarctions and sudden deaths, are caused by plaque rupture.3 The focus of this literature review is to provide an update as to which cardiac imaging techniques are currently in use for plaque stability and analyze them. This review will also summarize the factors that affect plaque stability and the future implications for imaging.

Pathophysiology of atherosclerosisAtherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition that occurs due to an accumulation of plaques in the arterial wall eventually becoming more solidified, causing an attenuation of the flow of blood through the vessel.4 It is the largest cause of cardiac mortality worldwide and is primarily responsible for major cardiovascular diseases including myocardial infarction and strokes.5

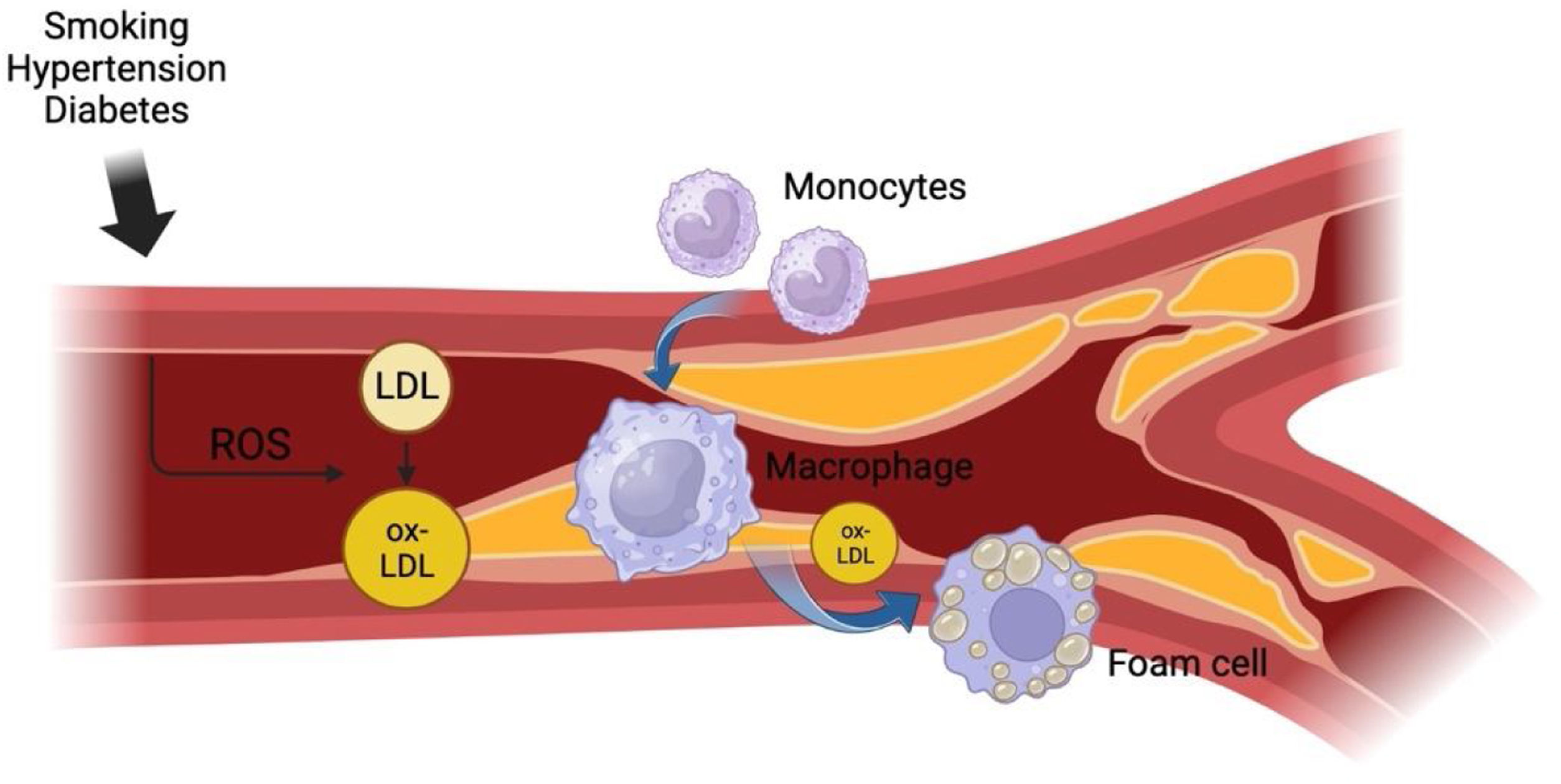

Gradually, the accumulation of foam cells in the intimal layers of the arteries forms a fatty ‘lipid core’ which is sheathed by a fibrous cap made from fibrous connective tissue.10–12 There are inflammatory markers that are also released from foam cells and contribute to an enlarged lipid core by stimulating the proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the medial layer of the arterial wall which then migrates to the existing lipid core to add further insult to the problem.13 Ultimately, this process results in the formation of an atheroma which can further enlarge and undergo calcification, thus causing pressure on the artery wall and occluding the opening of the vessel. The complications of atherosclerosis can then be identified by whether these plaques remain stable or rupture completely, causing a host of further issues such as angina, myocardial infarctions, or strokes. This process is summarized in Fig. 1.

Process of atherosclerosis. This figure provides a summary of the process of atherosclerosis. In its initial stages, various risk factors responsible for atherosclerosis cause direct insult to the arterial endothelium. Such factors include smoking, hypertension, and diabetes which cause endothelial damage by introducing free radicals into the bloodstream. Free radicals are responsible for imposing high-pressure forces on the arterial walls, altering cell metabolism in the endothelium.6 The damaged endothelium subsequently provides the prime environment for high levels of circulating LDL to accumulate in the walls of the arteries and then be oxidized into lipids which initiates a chronic inflammatory response in the walls of the intima.7 Monocytes then appear at the site of the inflammatory response and differentiate into macrophages, which become filled with fat from phagocytosing the newly oxidized lipids to become foam cells.8,9 Diagram created with BioRender.com.

Stable plaques are those that have a lower chance of rupturing or dissociating from the blood vessel. They carry lower risk and complications in the patient. Conversely, unstable plaques have a higher risk of rupturing and can be fatal.14 Unstable plaques not only occlude arterial blood flow but also damage the blood vessel wall in the detachment process, sometimes forming a thrombus.15 Together, these contribute to under-perfusion and subsequent ischaemia of tissues. Furthermore, the plaque may become fully mobile and travel elsewhere in the body, causing occlusion there too. Morbidity or mortality will be based on the location and extent of obstruction, with outcomes ranging from stroke, and myocardial infarction, to eventual death.16

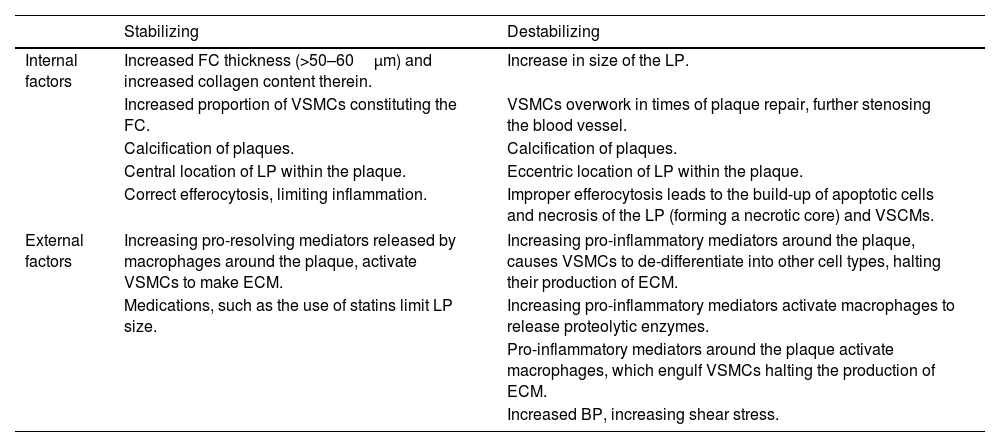

To prevent negative outcomes, plaques especially vulnerable to rupturing should be located, monitored, and treated promptly. A plethora of factors can affect the integrity of plaques which are summarized in Table 1. Whilst imaging patients with suspected plaques, if these factors – or any deviations from them – are encountered, the integrity of the plaque can be ascertained. This can then inform the choice of treatment for that patient, and in the long-term, guide preventative measures and stratification of unstable plaques in future cases and literature.14

A summary of factors contributing to the stabilization or destabilization of a plaque.

| Stabilizing | Destabilizing | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal factors | Increased FC thickness (>50–60μm) and increased collagen content therein. | Increase in size of the LP. |

| Increased proportion of VSMCs constituting the FC. | VSMCs overwork in times of plaque repair, further stenosing the blood vessel. | |

| Calcification of plaques. | Calcification of plaques. | |

| Central location of LP within the plaque. | Eccentric location of LP within the plaque. | |

| Correct efferocytosis, limiting inflammation. | Improper efferocytosis leads to the build-up of apoptotic cells and necrosis of the LP (forming a necrotic core) and VSCMs. | |

| External factors | Increasing pro-resolving mediators released by macrophages around the plaque, activate VSMCs to make ECM. | Increasing pro-inflammatory mediators around the plaque, causes VSMCs to de-differentiate into other cell types, halting their production of ECM. |

| Medications, such as the use of statins limit LP size. | Increasing pro-inflammatory mediators activate macrophages to release proteolytic enzymes. | |

| Pro-inflammatory mediators around the plaque activate macrophages, which engulf VSMCs halting the production of ECM. | ||

| Increased BP, increasing shear stress. | ||

BP: blood pressure, ECM: extracellular matrix, FC: fibrous cap, LP: lipid pool, VSMC: vascular smooth muscle cells. Table contents compiled from Refs.15,17–22,25–27.

Whilst Ezetimibe, a drug used for LDL-C lowering therapy, has other clinical benefits it does not appear to have an effect on stabilization of coronary plaques.17 The results of a meta-analysis of the effects of ezetimibe also conclude this.18

Internal factors affecting plaque stabilityOne well-researched factor that favours the stability of plaques is a thick fibrous cap,19 of more than 50–60μm.15,19 The more collagen present, the more robust the cap is.20 A larger lipid pool within the plaque core increases the risk of plaque rupture, in addition to lipid pools found more eccentrically within the plaque. Therefore, a combination of a thick fibrous cap encasing a smaller, centrally located lipid pool is favourable and less likely to rupture.19,21 In addition, more vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) being present in the fibrous cap will stabilize the plaque, as they release extracellular matrix (ECM) content; this strengthens the cap, making the overall plaque structure less vulnerable to shear stress and anchoring it to the intima.22 However, given the context, VSMCs can also be considered detrimental to the stability of a plaque. During a subclinical plaque rupture, VSMCs will accumulate rapidly at the rupture site and secrete ECM to stabilize the plaque. However, this can cause excessive stenosis and occlusion of the blood vessel, increasing the pressure of blood forced to travel through an even smaller lumen.23 Efferocytosis – the engulfing of apoptotic cells – by macrophages forms a part of atherosclerosis. However, when macrophages are in a pro-inflammatory environment, this causes stunted efferocytosis function, thus un-engulfed cells in the plaque and formation of a necrotic core.24 Necrosis also ensues, with VSMCs being degraded too – alongside their role of sustaining the ECM.15

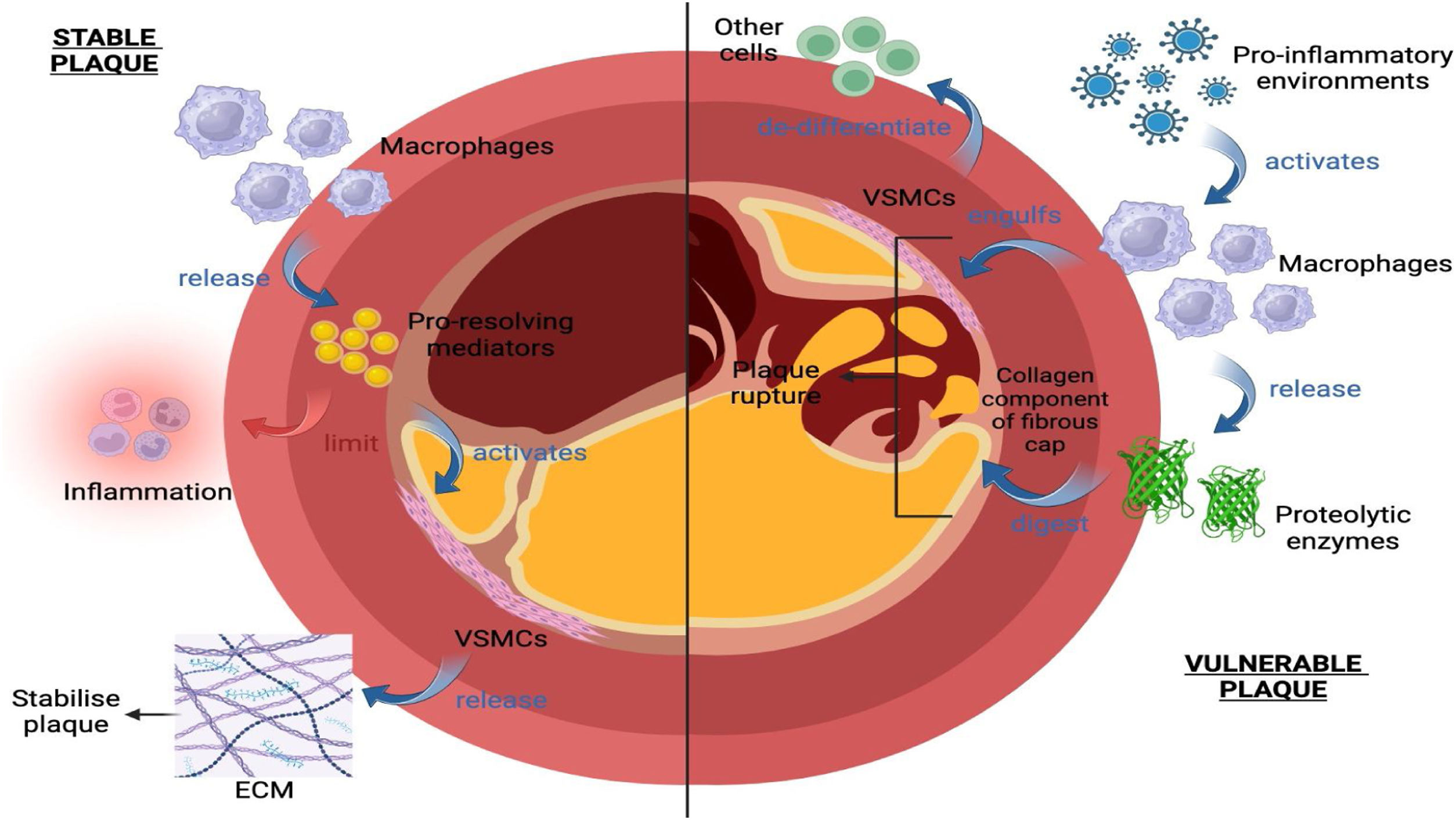

External factors affecting plaque stabilityThe surroundings of a plaque can also affect its integrity. The process of atherosclerosis is known to be associated with some level of chronic inflammation. However, unstable plaques are associated with more salient inflammatory processes.25 Pro-inflammatory environments activate macrophages which release proteolytic enzymes that digest the collagen component of the fibrous cap, leading to its degradation.16 Furthermore, macrophages engulf cells, including VSMCs.15 Breakdown and hindering production of the ECM can therefore lead to plaque instability and subsequent rupture.26 Additionally, when macrophages release pro-inflammatory mediators, they cause VSMC to de-differentiate into other cells, thus limiting the depositing of ECM, and consequently the plaque de-stabilizes.27 However, macrophages can also work with VSMCs to instead stabilize plaques; in the right environment of mediators, macrophages can release pro-resolving mediators which limit inflammation. These mediators activate VSMC to release ECM to stabilize the plaque.24

Medications like statins are external factors that can stabilize plaques. Statins generally work to decrease cholesterol levels in patients. With a limited supply of cholesterol, the lipid core found within plaques cannot grow as big, which favours stabilization.28 However, the effect of this is minimal, even at higher doses of statins. One recent cohort study found that statins also work to increase the density of calcium within the plaques.14 The effect of calcium content on plaques has been increasingly studied in recent years. Calcium has both stabilizing and destabilizing effects on plaques. Which end of the spectrum it falls into will depend on many factors such as the calcification size, number of, shape, the pattern it is laid down in, its surrounding environment, and much more.29 The equally stabilizing and destabilizing effects of calcium on plaques highlight an exciting area of potential future research. These factors are summarized in Fig. 2.

External factors affecting plaque stability. Under pro-inflammatory conditions, macrophages (1) release proteolytic enzymes that digest the collagen component of the fibrous cap, (2) engulf vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), and (3) release pro-inflammatory mediators that cause VSMCs to de-differentiate from other cells, limiting the deposition of ECM. This leads to plaque instability and subsequent rupture; Under the right environment of mediators, macrophages instead release pro-resolving mediators that limit inflammation and activate VSMC to release ECM, stabilizing the plaque. Diagram created with BioRender.com.

In summary, the many factors affecting plaque stability can coexist and often communicate – either strengthening or attenuating one another. The identification of many factors affecting plaque stability is also mirrored in the many imaging modalities available for plaque stability assessment. Each modality will have varying levels of effectiveness in identifying specific factor(s) and their nuances, as discussed in the next section.

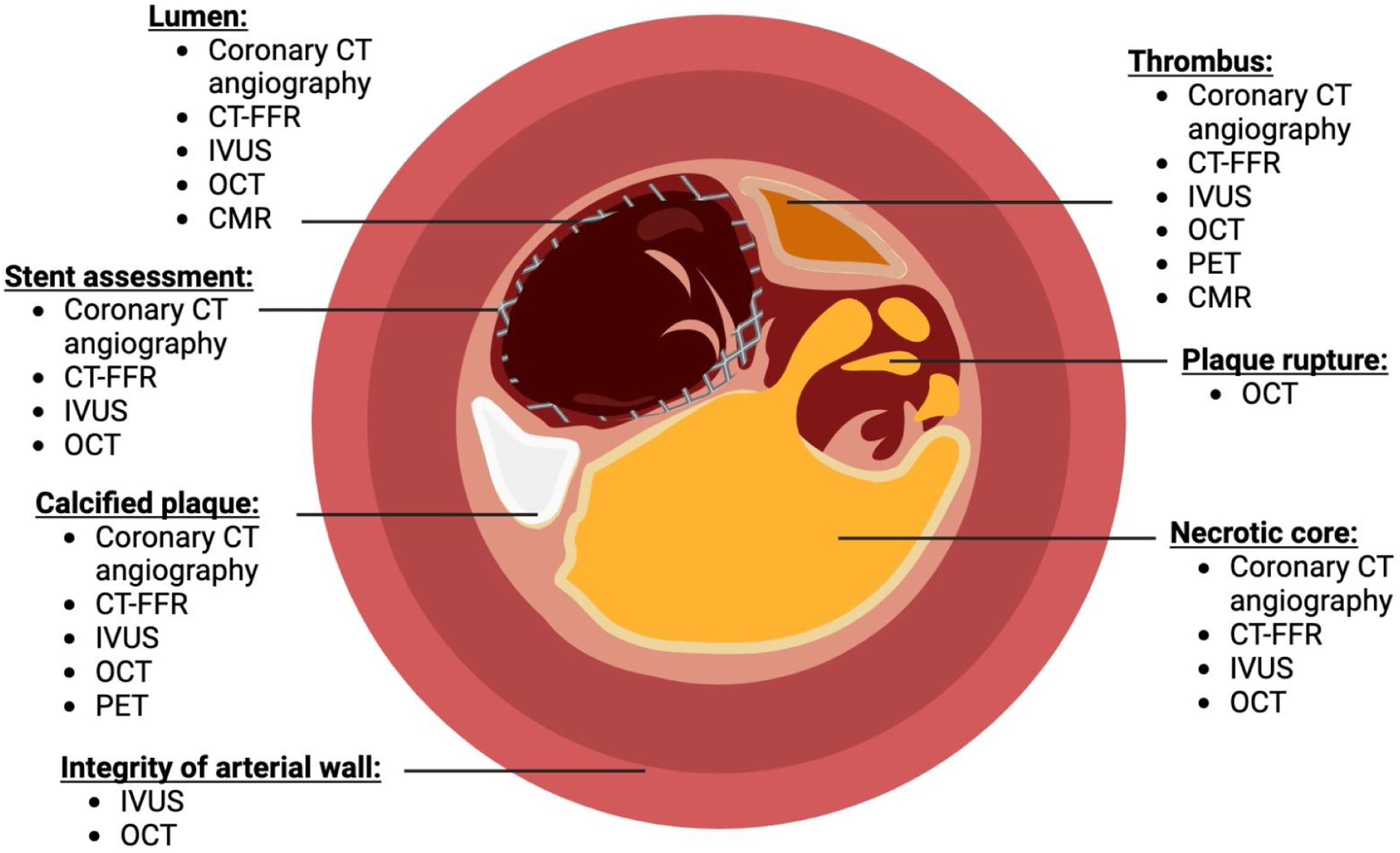

Different imaging modalitiesCoronary angiographyInvasive coronary angiography involves threading a catheter through a major artery and injecting a liquid contrast medium that can be detected by X-rays.30 While this procedure is an invasive approach it enables the clinician to determine the quality and flow of blood through the vessel, helping in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular diseases, and other common cardiac conditions.30 The imaging result can be seen in Fig. 3.

How different imaging modalities can be used to assess coronary plaque stability. Different components such as lumen of the artery, stent assessment, atherosclerotic plaques, integrity of the arterial wall, presence of thrombus, plaque rupture, and necrotic core could be identified. Figure complied from Refs.32–59. Diagram created with BioRender.com.

Recently, there have been studies suggesting the clinical advantages of CT coronary angiography – an alternative, non-invasive procedure where a bolus of low radiation contrast medium is detected by a CT scanner to produce high-quality images of the coronary artery Tree.1 This method is able to gauge factors such as spatial and temporal resolution, allowing the smallest of structures to be clearly differentiated.31 CTCA also offers insights into prognosis by assessing the occurrence and sites of coronary atherosclerosis.32 However, it may have limitations in complex coronary artery disease situations, particularly involving heavy calcifications, stents or bypass grafts where artefacts are more prone, leading to an overestimation of the degree of calcification.33

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is another imaging procedure that is often used not only for imaging purposes but the management of atherosclerotic plaques by guiding stent insertion.34 A catheter containing a transducer is advanced using a guidewire past the target lesion and settled in place. The transducer is responsible for emitting high-frequency ultrasound waves into the tissues being investigated and a pullback device is used to guide the transducer through the area of interest, allowing for a series of grayscale images to be obtained.35 All three layers of the coronary artery: the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia can be identified using IVUS. The atherosclerotic plaques formed in the tunica intima tend to have less echogenicity compared to the highly reflective tunica adventitia, while the smooth muscle cells in the tunica intima do not reflect any of the ultrasound waves, thus appearing dark grey in the presenting Images.36,37

Optical coherence tomography (OCT)Newer literature suggests the efficacy of utilizing optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the imaging of coronary arteries. This method adopts infrared light technology to produce cross-sectional images of the arterial wall with a resolution of up to 10μm.38 Studies suggest that this resolution can accurately identify the integrity of the arterial wall and therefore any vulnerable plaque features such as thin cap fibroatheromas.39 It achieves this using a technique called low-coherence interferometry where information is collected by a catheter measuring the delay in time taken for light to be reflected from the tissues being investigated back to a detector. Light is also emitted through a reference arm to allow for a time difference to be calculated and establish an interference value which is used to create a cross-sectional image by gathering data regarding the depth of tissue.40

However, the use of OCT has been criticized due to the flow of blood weakening the signal and not providing an accurate enough picture of the full lesion.41 Despite this, one multicenter study evaluating the safety and efficacy in comparison to intravascular ultrasound imaging found no serious complications due to the procedure, enabling the imaging of the lumen border.42 OCT can differentiate between fibrous tissues, collagen, calcium, and lipid composition, therefore widening the potential to examine different causes of artery occlusion.43

Positron emission tomography (PET)Positron emission tomography (PET) scans are also indicated in various diagnoses of cardiac injuries. When radiotracers undergo decay and release positrons, they interact with electrons, resulting in the emission of photons that can then be sensed by detectors.44 Through this process, radiotracers have been designed to target specific molecules within the plaques, allowing the extent of myocardial perfusion to be analyzed. In the specific case of atherosclerotic plaques, F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is an example of one tracer that has been used due to its similar chemical composition to glucose, accumulating in macrophages where a higher FDG uptake in vessels demonstrates areas consisting of atherosclerotic plaque.45 Additionally, sodium F-Fluoride is another commonly used radiotracer due to its detection of the molecular calcification within plaques.46

The distribution of the radiotracer through the myocardium is translated into images that are presented in three different orientations that are amalgamated to compare perfusion across the different axes; any impaired perfusions would indicate scarring of the myocardium where the extent of damage can be assessed further.47

While PET imaging is advantageous in the sense that it can provide high specificity, the spatial resolution is markedly lower compared to other techniques, increasing the difficulty in which structures can be established and differentiated over smaller distances.48

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMR)Another imaging modality that has been undergoing further updates in terms of guidelines, new technologies, and current trials is the use of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMR). Newer quantitative methods are being adopted to help in the assessment of ischaemic heart disease, myocarditis, and cardiomyopathies.49 For example, T1 mapping can be used to create grey-scale images of myocardial changes by measuring the longitudinal relaxation times of the tissues. This can be utilized as a biomarker alongside extracellular volume (ECV) when isolated to its native T1 form; in other words. the time taken in the absence of contrast. The ECV is calculated when gadolinium is administered to calculate the post-contrast T1 value, which in some studies has provided use in predicting outcomes in some cardiac abnormalities including subendocardial fibrosis.50

Computed tomography-derived fractional flow reserve (CT-FFR)Computed tomography-derived fractional flow reserve (CT-FFR) is a new technology that is non-invasive and provides information about the consequences of restricted blood flow with regard to a specific coronary lesion.51 FFR is the fraction of maximal flow that can occur across a coronary stenotic lesion. Previously, calculating FFR was invasive and not cost-effective52 however a trial of over 1200 patients has shown the cost-effectiveness of CT-FFR.53 CT-FFR allows for haemodynamically significant coronary artery disease to be identified which is one of the main limitations of CT angiography.52 The benefits of having CT-FFR available onsite for patients have also been investigated. The results of one trial showed that having CT-FFR available onsite reduced the number of patients undergoing invasive angiography without obstructive disease but did not have an effect on major adverse cardiovascular events at one year.53

Imaging modalities for assessing plaques in different blood vessels: similarities and differencesAs highlighted in the previous section, the main imaging modalities used for detecting cardiac disease are ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which have diverse methods and details of image acquisition that give them the potential to detect vascular disease in both coronary and non-coronary vessels.

US can be non-invasive (doppler) and invasive (IVUS) having the most accuracy when used on superficial vessels, such as carotids and limb arteries. Non-invasive US can differentiate components in the arterial wall, detect the pathological proliferation of the intimal-medial layer of the superficial vessels, and calculate the total plaque area. Hence, it is useful in locating signs of early plaque formation and is often used as a first-line imaging modality.54 On the other hand, the IVUS provides images from within the lumen whereby it can visualize the fibrous and fibrofatty plaques as well as the lipid-rich necrotic core and dense calcium. In addition to carotid and limb vessels, the IVUS can be used on the coronary arteries, but both invasive and non-invasive US scans can show obscured images due to acoustic shadows from the mineralized calcium deposits within the vessels.55 Several studies have found that when the lipid core was accurately recognized by IVUS, plaques that were associated with ACS often were hypoechoic.55 Additionally, multiple large-scale studies have highlighted some technical constraints of this imaging modality such as low spatial resolution and operator-dependent parameters with limitations in cardiovascular risk stratification.54,55

The other widely used imaging modality that is usually preferable to US, OCT, and PET is CTA which overcomes their limitations with a high spatial resolution that allows for the atherosclerotic plaques to be quantified and characterized. CTA can detect multiple features of plaque vulnerability including intraplaque haemorrhage (IPH), lipid-rich necrotic core (LPNC), thin fibrous cap (TFC), neovascularization, plaque thickness, total volume and components, and surface morphology. It allows for the evaluation of vessels from the aortic arch to the circle of Willis as well as the coronary arteries and detects changes in cerebral parenchyma within one session making it a fast and accurate test with the least amount of discomfort to the patients.56 Furthermore, data from a clinical trial identified that CTA is able to detect high risk plaques (with factors such as positive remodelling). These features were shown to be predictors for the development of ACS.57 Nevertheless, despite the aforementioned benefits, CTA exposes patients to ionizing radiation with a risk of adverse reactions to the iodine-based contrast agents and can overestimate the burden of the disease when imaging heavily calcified plaques. Additionally, there is a lot of debate in the literature regarding the capability of CTA to differentiate soft tissue components such as IPH and LPNC accurately, especially in cases of small plaques where high-resolution MRI is preferable.57

High-resolution MRI is considered to be the most accurate and versatile non-invasive imaging modality for atherosclerotic plaques. It allows for the differentiation of plaque components based on biophysical and biochemical parameters such as water content, chemical composition, molecular motion, and physical state. This is achieved by combining multi-contrast images such as black blood that includes T1, T2 and PD weighted sequences with suppressed blood flow signal and bright blood that includes time of flight (TOF) sequences with enhanced blood flow signal.58 Hence, black blood sequencing is preferred for high-flow vessels and bright blood sequencing is preferred for slow-flow vessels when evaluating atherosclerotic plaque composition, morphology, and vulnerability. This versatility makes MRI appropriate for peripheral, coronary, aortic, carotid, and cerebral arteries. Additionally, unlike CTA, MRI imaging does not cause ionizing radiation and can be sequentially repeated. However, MRI is subject to flow void artefacts and frequently overestimates the extent of vessel plaques. Additionally, to have the MRI, patients need to fit a certain criterion such as having no metals in the body and no claustrophobia because the scan entails lying completely still in a closed space for a long period.59

Risks associated with imagingCoronary angiographyLike most invasive procedures, diagnostic invasive coronary angiography (CAG) can cause serious complications. Major complications include myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, ventricular arrhythmia, vascular complications, contrast reactions, and death. The likelihood of these complications shows a positive correlation with the severity of the underlying disease. Important factors that can predict such major complications include acute MI of <24h, unstable angina, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, shock, renal insufficiency, and older age. Patients undergoing emergency CAG have the highest risk of complications. Other important factors include the skillset and experience of the operator and catheterization laboratory staff, in addition to peri-procedural management and low-profile catheters. At present, the trans-radial approach has been shown to reduce entry site complications compared to the femoral approach.

According to the current analysis, the acute risk of death associated with CAG was estimated to be 8/10,000 studies and the frequency of serious adverse events was 177/10,000.60,61

Invasive CAG requires an iodinated contrast agent to be injected and there are certain risks associated with this. Adverse events after the use of contrast media include acute or delayed reactions, local effects (extravasation), and contrast-induced nephropathy. Extravasation occurs in approximately 0.2% of procedures when a power injector is used and can lead to severe damage, including compartment syndrome.62 Mild reactions happen in 0.4% of patients and serious adverse reactions, such as severe hypotension, pulmonary oedema, and loss of consciousness, occur in 0.04% with non-ionic contrast agents.63

The most notable risk of iodinated contrast agents is nephrotoxicity, albeit rare in patients without a history or symptoms of renal pathology. The occurrence of kidney injury after a percutaneous coronary intervention was 1.3%.64 Intravenous injections had lower nephropathy rates compared with intra-arterial injections. (1.1 and 1.8%, respectively).63,64 Patients with existing kidney failure had additional mortality as high as 14–15.8%.64-66

Another study estimated the death rate for contrast agents due to acute general reactions to be 0.059/10,000 and long-term risk due to nephropathy to be 6.6/10,000 for intravenous and 7.6/10,000 for intra-arterial administration.67 The rate of severe acute adverse effects was an estimated 4.06 and long-term events 79.0 per 10,000 studies.

Positron emission tomography (PET)In the current era, a cardiac PET scan is a very safe procedure to do. The only significant complication associated with PET scans is radiation exposure and radiation-related adverse effects. Advances in image acquisition and new software methods offer dose reduction in cardiac PET imaging, as previously the 3D PET technology was associated with notable exposure to radiation.

Newer PET software also has the added advantage of allowing the reconstruction of absolute myocardial blood flow as well as relative myocardial perfusion data from the same scan. It is now also possible to obtain high-quality perfusion images at doses as low as 20mCi due to increased PET sensitivity.68

Future implicationsCurrently, there is no definitive modality of choice of imaging for plaque stability. No method can provide exact information on the vulnerability of an atherosclerotic plaque.69 Many of the imaging modalities discussed provide partial, morphological information. Therefore, further research is firstly required into plaque stability factors as well as the effectiveness of imaging modalities in combination with one another.

There needs to be a big transformation away from assessing stenosis severity solely. It may be possible to categorize low and medium-risk people who are actually at a high risk of suffering a severe cardiovascular event by identifying high-risk plaque characteristics.70 The biggest clinical need in current cardiovascular imaging is correctly identifying this group. The drawbacks of current stenosis-driven approaches are addressed by incorporating innovative imaging techniques. The next significant development in the evaluation of atherosclerotic plaques is the application of these various imaging modalities in clinical settings. Current studies on the application of metabolic imaging hold promise for the early detection and prognosis of the course of cardiovascular disease.54 The translation of cutting-edge imaging techniques into standard clinical practice will be made more informed by these investigations.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this review has identified factors affecting plaque stability, the use of different imaging modalities, and the risks associated with them. We have also identified potential areas for future research. This includes researching the effects of calcium further, given its ability to be both a stabilizing and destabilizing factor. Given the risk of major complications associated with invasive coronary angiographies, more research should be done into non-invasive techniques. This is especially important due to the advantages of coronary CT angiography which is more efficient and cost-effective.33 Furthermore, other modalities such as PET can provide a higher specificity and OCT can provide a better resolution.38,46 Although, these methods do have disadvantages with a low spatial resolution with PET and problems with viewing full lesions using OCT.41,46 The risks of coronary angiographies and PET have been identified; however, further investigations could be pursued to identify potential risks of utilizing OCT. Invasive and non-invasive ultrasonography has been identified to produce accuracy in superficial vessels. Conversely, high-resolution MRI has been identified to be highly accurate in atherosclerotic plaques. However, changes according to imaging on plaque stability in different blood vessels could be further investigated to identify similarities and differences.

ConcessionsNone.

Importance of workThank you for considering our review paper. We wish to publish this in your well-esteemed journal as a priority for various reasons. The field of cardiac imaging modalities in assessing arterial plaques is progressing. As such, it is pertinent to provide a review like ours, which can guide clinical practice whilst considering not just the efficacy but also the safety of different modalities. Our review provides a summary of the differences between the modalities, such as which modality offers better visualization for specific components of a plaque, which modality is better suited to image which blood vessel type, as well as the risks associated with the modalities. This review is important as it will better inform the field of imaging modalities, which is much needed given the sustained rise in plaque disease.

Contact details of an expertDr Veronica Carroll, Senior Lecturer in Vascular Biology.

Email: vcarroll@sgul.ac.uk.

DeclarationAll authors have participated in the work and have reviewed and agree with the content of the article.

None of the article contents are under consideration for publication in any other journal or have been published in any journal.

No portion of the text has been copied from other material in the literature (unless in quotation marks, with citation).

I am aware that it is the authors responsibility to obtain permission for any figures or tables reproduced from any prior publications, and to cover fully any costs involved. Such permission must be obtained prior to final acceptance.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest were declared in the making of this manuscript.