New horizons in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia

More infoThe role of LDL cholesterol as a causal agent of arteriosclerosis is scientifically consolidated. A number of seminal clinical trials of the highest scientific quality (randomized, controlled, double-blind versus placebo) in the last 40 years have confirmed that lipid lowering therapy with progressively ambitious therapeutic goals is associated with reductions in cardiovascular complications in the absence of major side effects at least up to the range of 30 mg/dL of LDL cholesterol. Drugs that have demonstrated these effects act by reducing circulating LDL cholesterol by upregulating the LDL receptor, independently of their primary action: inhibition of synthesis (statins, bempedoic acid), or absorption of cholesterol (ezetimibe) and promoting recycling of the LDL receptor via PCSK9 blockade. The early reduction of LDL cholesterol and its maintenance over time reinforce the protective effect of these drugs. Additional efforts are needed to improve the LDL control of high-risk patients to reduce their cardiovascular complications.

El papel del colesterol LDL como agente causal de la arteriosclerosis está científicamente consolidado. Diversos ensayos clínicos de la máxima calidad científica (aleatorizados, controlados, doble ciego frente a placebo) en los últimos 40 años han confirmado que el tratamiento hipolipemiante con objetivos terapéuticos progresivamente ambiciosos se asocia con reducciones de complicaciones cardiovasculares en ausencia de efectos secundarios importantes al menos hasta el rango de 30 mg de colesterol LDL. Los fármacos que han demostrado estos efectos actúan reduciendo el colesterol circulante mediante la regulación al alza del receptor LDL, independientemente de su acción primaria: inhibición de la síntesis (estatinas, bempedoico), o absorción del colesterol (ezetimba) y favoreciendo el reciclaje del receptor de LDL via bloqueo de PCSK9. La precocidad de la reducción del colesterol LDL y su mantenimiento en el tiempo refuerzan el efecto protector de los mismos. Es necesario un esfuerzo adicional para mejorar el control de los pacientes de alto riesgo para reducir sus complicaciones cardiovasculares.

The determinant role of circulating cholesterol as an aetiological agent of atherosclerosis has been thoroughly reviewed in the preceding article to this monograph. Epidemiological, biological, pathophysiological, genetic, and intervention studies provide a remarkably consistent account of the role of elevated cholesterol in causing atherosclerosis.1,2

However, from a clinical point of view, what is relevant is whether we can carry out interventions that, by reducing circulating cholesterol, result in a clinical benefit in terms of reduced cardiovascular complications, cardiovascular mortality and, ideally, mortality, in the absence of significant side effects.

Statins: demonstrating the conceptAs early as 40 years ago, studies by the Lipid Research Clinics indicated a modest clinical benefit of cholesterol lowering with the use of cholestyramine. However, statins, inhibitors of the limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis (HMG-CoA reductase), were the drugs that very consistently demonstrated in the late 20th century that lowering circulating cholesterol levels could translate into a reduction in cardiovascular complications1–3 (Fig. 1). The landmark 4S study4 evaluated the effect of 40 mg of simvastatin in 4440 patients with established vascular disease (acute myocardial infarction [AMI] or angina pectoris) and elevated cholesterol levels (5.5–8 mmol/L over 5.4 years). Simvastatin reduced total cholesterol levels by 25% and LDL cholesterol levels by 35%. This reduction was associated with an impressive 30% reduction in all-cause mortality (95% CI 15–48), which was mainly due to a 42% reduction in coronary mortality (95% CI 27%–54%). This demonstrated the protective effect of simvastatin in patients with frank hypercholesterolaemia (mean LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) 188 mg/dL) in secondary prevention. The 4S extension study showed that the benefit in reducing total and cardiovascular mortality persisted after an additional five years of follow-up, despite open-label simvastatin treatment in both groups.5

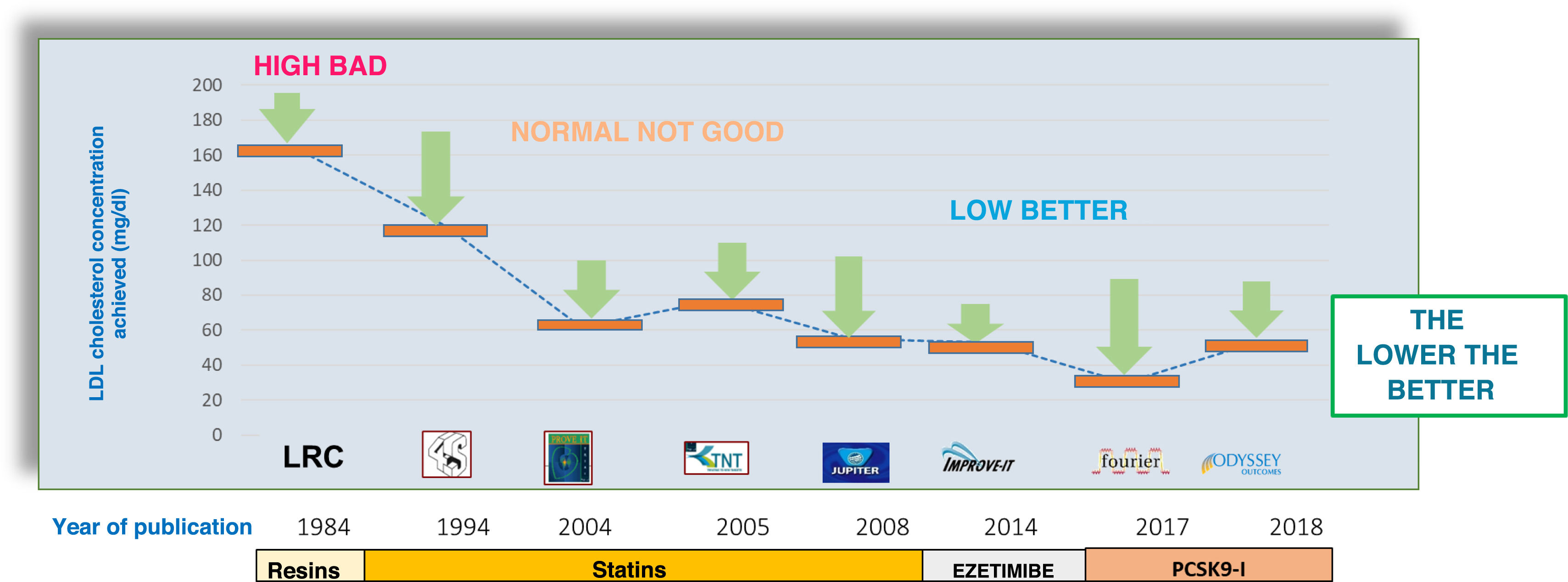

LDL cholesterol levels in clinical trials and cardiovascular benefit.

Several lipid-lowering therapies have demonstrated the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy in reducing cardiovascular complications with clinical benefit for patients in controlled clinical trials with progressively decreasing LDL-cholesterol levels. The most ambitious goals have been achieved with statin monotherapy (JUPITER [Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin]), combined statin/ezetimibe therapy (IMPROVE-IT), and the recent trials with PCSK9 inhibitors (Fourier and ODYSSEY Outcomes).

Shortly thereafter, the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS)6 investigated whether lipid-lowering therapy would have a clinical benefit in patients without a history of AMI. WOSCOPS evaluated the effect of pravastatin in 6595 middle-aged men with elevated LDL-C (mean 192 mg/dL). Pravastatin reduced LDL-C levels by 26% and was associated with a 31% (95% CI 17%–43%) reduction in the rate of AMI or vascular death at 4.9 years, with a reduction in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at the limit of statistical significance. The beneficial effect was consolidated with a legacy benefit7: 15 years after the end of the study, all-cause mortality was 13% lower in the pravastatin group (hazard ratio [HR] .87, 95% CI .80–.94), mainly due to a reduction in cardiovascular mortality (HR .79, CI .69–.90).

Statins: the lower the better…A decade after the 4S (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study) and WOSCOPS studies, another step forward was necessary: the consolidation of intensive treatment. Two pivotal trials investigated whether the intensity of lipid-lowering treatment provided significant additional benefits by comparing two strategies of different intensities.

PROVE-IT (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy -Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 22 Trial)8 was paradoxically designed to demonstrate non-inferiority of 40 mg pravastatin versus 80 mg rosuvastatin after acute coronary syndrome, based on the concept that there would be no significant benefit from intensifying lipid-lowering therapy with a “reference” statin. Contrary to the original hypothesis, PROVE-IT showed that lowering LDL cholesterol from 106 mg/dL to 62 mg/dL (atorvastatin 80 mg) versus 95 mg/dL (pravastatin 40 mg group) was associated with a 16% (95% CI 5–26 %) reduction in the risk of cardiovascular complications at 2-year follow-up.

Similarly, the Treating New Targets (TNT) study9 showed that lowering LDL-C from 80 mg to 77 mg/dL with atorvastatin compared with a control group of 101 mg/dL (atorvastatin 10 mg) was associated with a 22% (95% CI 11%–31%) reduction in cardiovascular complications.

These studies were instrumental in lowering the LDL-C target from 100 to 70 mg/dL in patients with established vascular disease.

More recently, rosuvastatin has shown that the benefit can extend to primary prevention patients with “normal” LDL-C levels (<130 mg/dL) but at increased CV risk due to elevated C-reactive protein, a marker of low-grade systemic inflammation.10 Patients in the treatment arm (rosuvastatin 10 mg daily) achieved LDL-C levels with a reduction of 46% (95% CI 31%–54%).

The cholesterol trialists' meta-analysis showed that the beneficial effect of statin therapy was directly related to absolute reduction in LDL-C: for every mmol/L (39 mg/dL) reduction, there was a 22% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular events in both statin versus placebo and intensive versus standard treatment trials.11,12

Intensive combined lipid-lowering therapyThe success of statins in cardiovascular prevention has made it difficult to demonstrate the beneficial effect of other lower-intensity therapies per se. IMPROVE-IT (IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial)13 provided two main messages: 1) treatment with ezetimibe provides additional benefit; 2) more ambitious targets continue to have cardiovascular protective effects. Indeed, the addition of ezetimibe to baseline treatment with 40 mg simvastatin in patients after acute coronary syndrome achieved a reduction in median cholesterol from 69.5 mg/dL to 53.7 mg/dL and required seven years of follow-up to demonstrate a reduction in cardiovascular complications (HR .936 95% CI .89–.99), consistent with the effect expected from the magnitude of the reduction achieved. This study has undoubtedly been instrumental in setting the ambitious target of 55 mg/dL in current cardiovascular prevention guidelines.

In statin-intolerant patients, the use of bempedoic acid has also shown a cardiovascular protective effect consistent with the lowering of LDL-C in the CLEAR (Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic Acid [ECT1002], an ACL-Inhibiting Regimen) Outcomes trial.14 Bempedoic acid was associated with a 21.1% reduction in LDL (29.2 mg/dL) and a 13% reduction in cardiovascular complications (95% CI 4%–21%). This molecule offers an oral treatment option of particular interest to statin-intolerant patients, but may also help to optimise LDL-C levels in statin-tolerant patients.

Interestingly, while the molecular targets of action of statins, ezetimibe, and bempedoic acid are unique, all three molecules concur in that their circulating cholesterol-lowering effect is mediated by (mainly hepatic) overexpression of LDL-C receptors. Other recent breakthroughs in lipid-lowering therapy have involved a more direct mechanism of maintaining high levels of LDL-C receptors.

PCSK9: a new target for lipid-lowering therapyThe identification of PCSK9 and the development of a highly potent lipid-lowering therapy within a few years has led to a remarkable advance in lipid-lowering treatment options. In brief, PCSK9 is a protein that, once the LDL receptor complex is internalised, promotes lysosomal elimination of the LDL receptor. In the absence of PCSK9, the receptor is recycled to the cell surface, allowing the cycle of cell internalisation of the LDL-receptor complex to be reproduced, resulting in a reduction in circulating cholesterol. Two main mechanisms have been developed to block the action of PCSK9: human mononuclear antibodies (alirocumab and evolocumab) and, more recently, small interfering ribonucleic acids (RNA) (siRNA, such as inclisiran), which will be discussed in later articles in this issue.

The Fourier (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk)15 and ODYSSEY Outcomes (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment With Alirocumab) studies16 clearly demonstrated that LDL cholesterol lowering with PCSK9 blockade is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular complications consistent with the potent LDL-C lowering achieved by this mechanism. In addition, both studies achieved particularly low levels of LDL-C, and therefore we have not yet reached an LDL-C ''floor'' below which cardiovascular benefits cease. The median LDL-C achieved in the Fourier intervention group was 30 mg/dL. Notably, there was no evidence of toxicity in patients who achieved even lower LDL-C levels, while the clinical benefit was shown to be greater in these patients.17 Similar results have been reported for alirocumab.18 PCSK9 blockade promotes the internalisation of cholesterol into the cell, making cellular toxic effects due to (circulating) cholesterol depletion unlikely.19 It is known that all cells in the body have the mevalonate pathway and are able to synthesise their own cholesterol,20 leading to the zero- (circulating) LDL hypothesis.3 This is a provocative hypothesis that shows how far we are from achieving ambitious goals in real clinical practice.

Adherence and timing matterCumulative exposure to elevated LDL-C levels is a key determinant of the development of atherosclerosis1 (Figs. 2 and 3). Conversely, a sustained reduction in LDL-C levels over time is a determinant of the beneficial effect of lipid-lowering therapy. In this respect, it is not only important to achieve a strong lipid-lowering effect, but also that the treatment is maintained over time.21 Unfortunately, epidemiological studies show that discontinuation of lipid-lowering therapy is a common occurrence, leading to an increase in the very cardiovascular complications we are trying to prevent. The development of lipid-lowering treatments that are less demanding in terms of patient discipline in taking multiple daily medications may facilitate better adherence to intensive treatment. In this respect, the use of small interfering RNAs may offer a paradigm shift in drug treatment. Inclisiran is an siRNA that offers sustained LDL cholesterol reductions of around 55% with six-monthly subcutaneous administration.22 Pending the results of vascular event trials, a meta-analysis of phase 3 trials shows that inclisiran treatment actually reduces “secondary vascular adverse events” compared to placebo, supporting a plausible therapeutic role in cardiovascular prevention.22

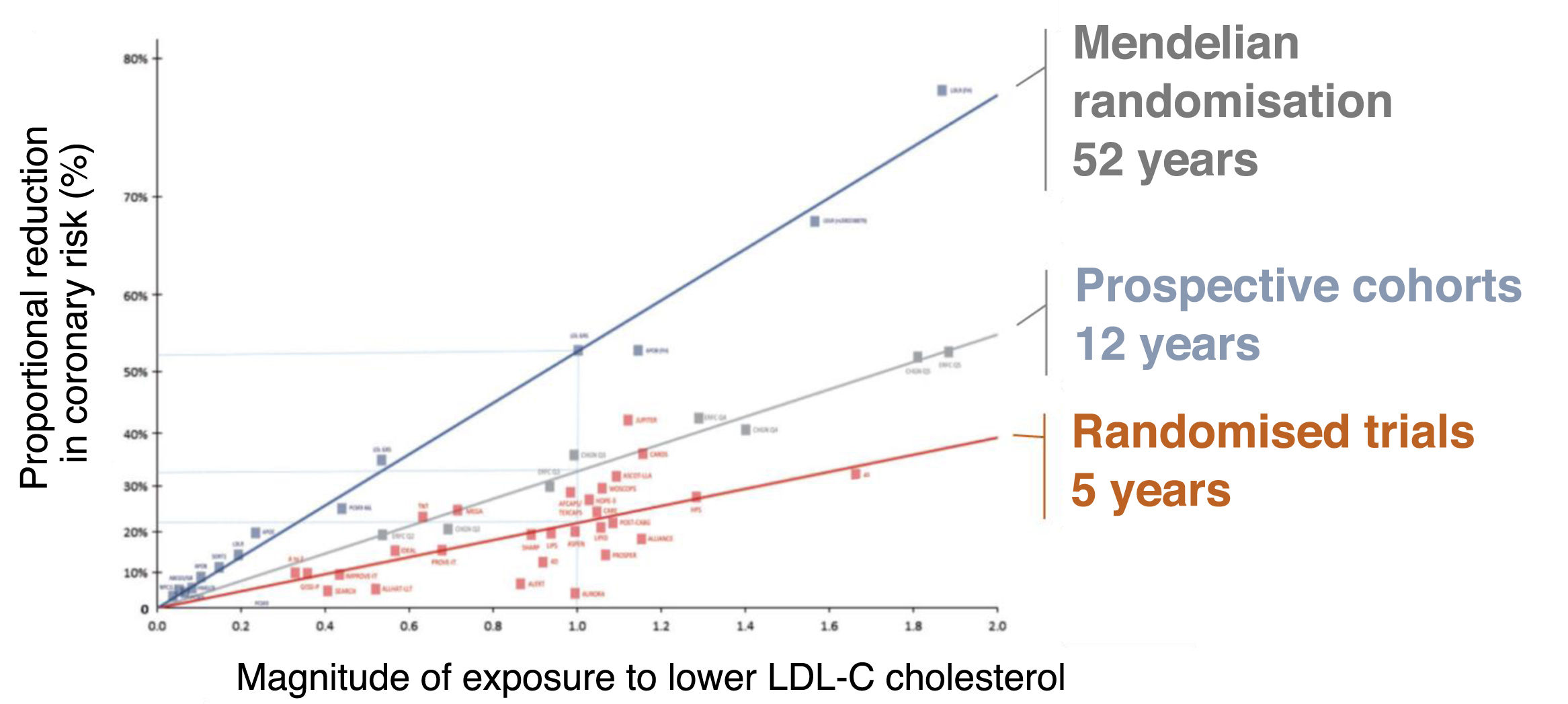

Relationship between magnitude and duration of exposure to different levels of LDL cholesterol and clinical benefit in different types of studies.

Relationship between magnitude of LDL cholesterol-lowering exposure and clinical benefit in randomised trials (typical duration 5 years), prospective cohorts (typical duration 12 years) and Mendelian randomisation studies (typical duration 52 years). As can be seen, longer duration of exposure to different cholesterol levels translates into a greater effect on cardiovascular complications.

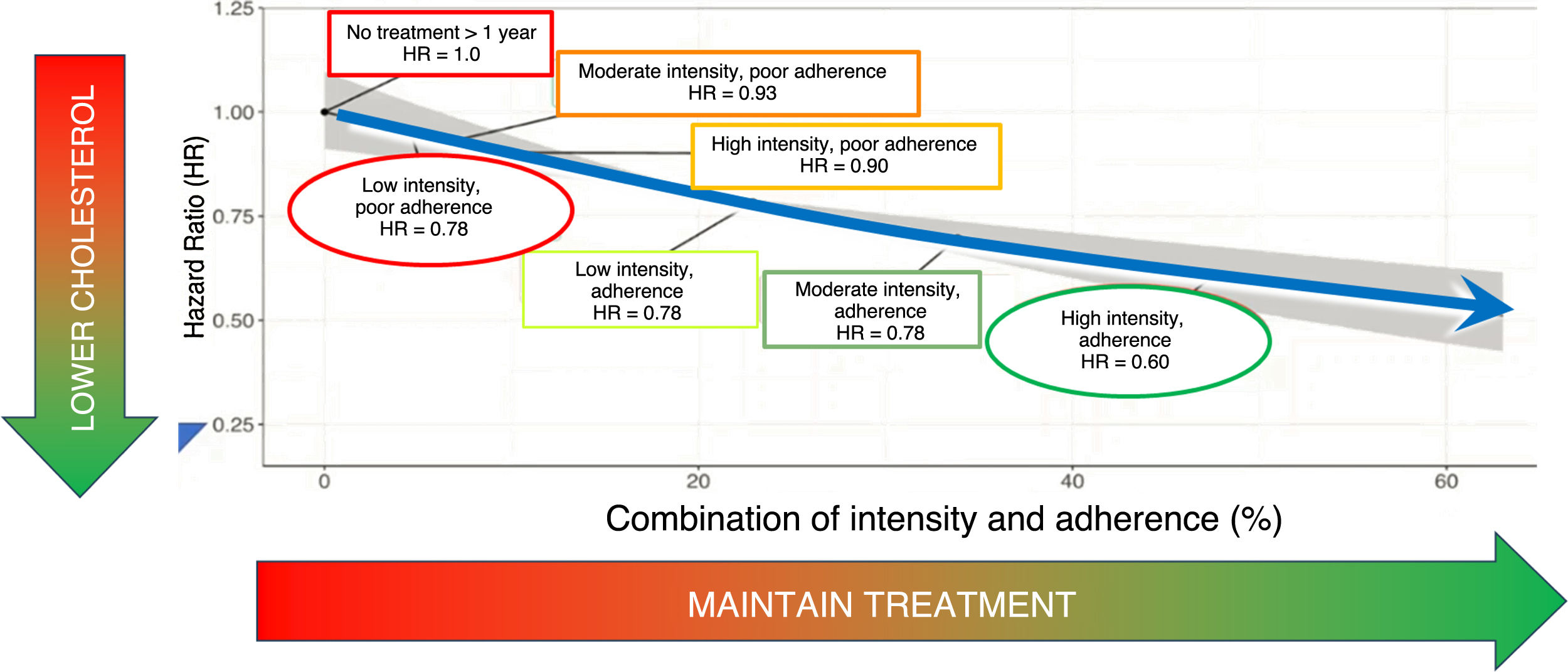

Importance of treatment maintenance on the cardiovascular protective effects of lipid-lowering drugs.

The cardiovascular protective effect is a combination of treatment intensity and adherence to treatment.

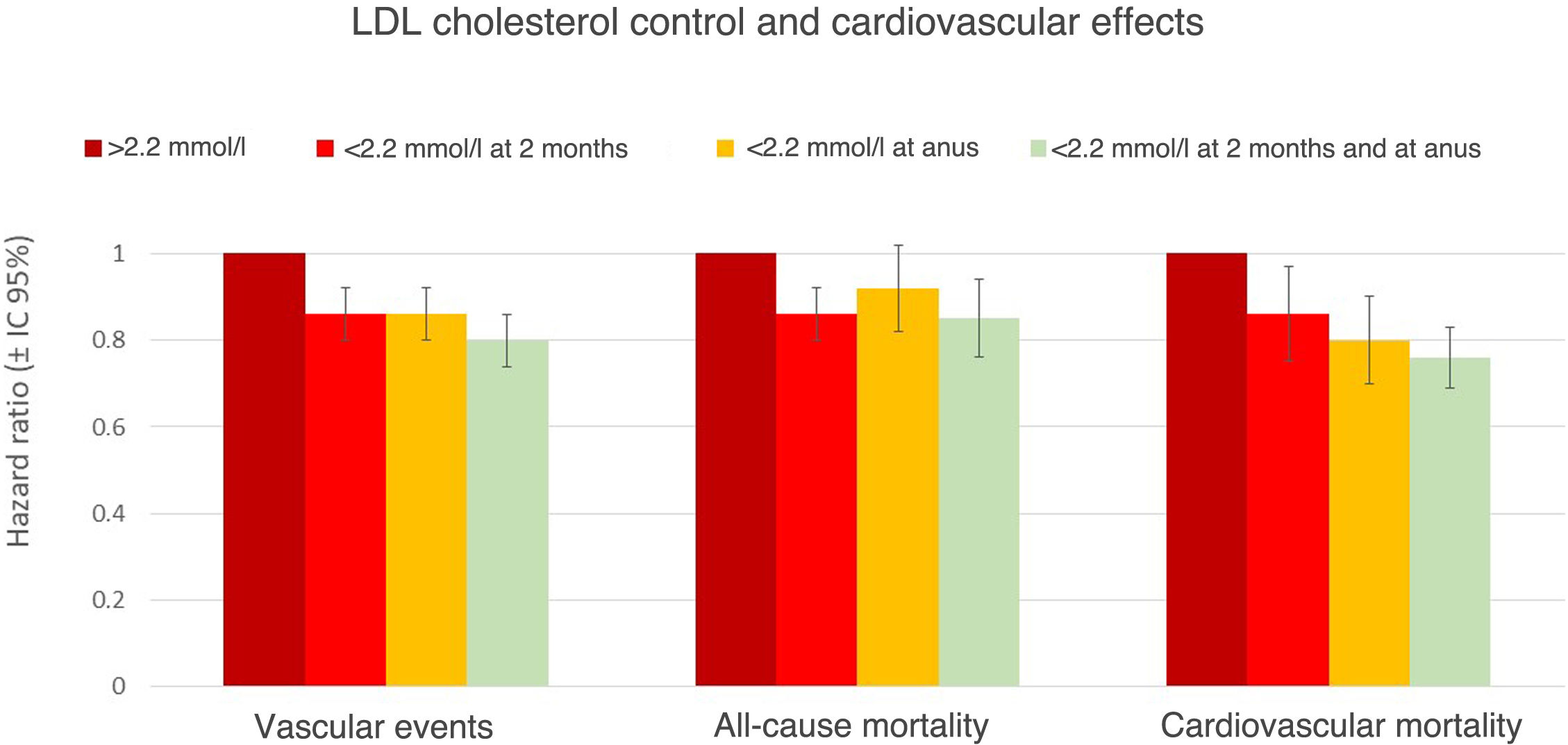

Another important factor is the delay in initiating intensive lipid-lowering therapy after a vascular event. The strategy of several successive steps with staggered use of drugs proposed by some guidelines23 leads to a delay in reaching therapeutic targets at a particularly vulnerable time for patients. Recent studies show that early achievement of ambitious lipid targets and their maintenance at one year is indeed associated with a more favourable prognosis in post-AMI patients24 (Fig. 3). We could say that it is “never too early” to achieve ambitious lipid targets, and we should look for mechanisms to maintain them in the long term (Fig. 4).

Cardiovascular protective effect of early and sustained non-HDL cholesterol lowering in patients after AMI.

The SWEDEHEART (Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) registry has recently shown the importance of early (two months) and sustained (measured at one year) lowering in reducing cardiovascular complications, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality after AMI.

In conclusion, various oral lipid-lowering treatments (statins, bempedoic acid, ezetimibe) ultimately lower circulating cholesterol through upregulation of the LDL receptor, reduce cardiovascular complications, and their effect is maintained beyond the therapeutic targets currently reflected in therapeutic guidelines. In addition, PCSK9 blockade, also by upregulating the LDL receptor, continues to provide benefits with its potent lipid-lowering effect at least up to around 30 mg/dL, with no evidence of a threshold below which protective cardiovascular effects cease to be achieved. In addition, early and sustained intensive lipid-lowering therapy is associated with improved cardiovascular prognosis. Further efforts are needed to use the available tools for sustained cholesterol reduction to improve the prognosis of patients at high vascular risk.

FundingThe author received support from Novartis for this article, which was written entirely by the author with no involvement from Novartis.

Additional informationThis article is part of the supplement entitled “New horizons in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia” , which was funded by the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis, with sponsorship from Novartis.

Please cite this article as: Guijarro C, El control estricto del colesterol aterogénico en la prevención de las enfermedades cardiovasculares. Clin Investig Arterioscl. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artere.2025.100744

![LDL cholesterol levels in clinical trials and cardiovascular benefit. Several lipid-lowering therapies have demonstrated the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy in reducing cardiovascular complications with clinical benefit for patients in controlled clinical trials with progressively decreasing LDL-cholesterol levels. The most ambitious goals have been achieved with statin monotherapy (JUPITER [Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin]), combined statin/ezetimibe therapy (IMPROVE-IT), and the recent trials with PCSK9 inhibitors (Fourier and ODYSSEY Outcomes). LDL cholesterol levels in clinical trials and cardiovascular benefit. Several lipid-lowering therapies have demonstrated the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy in reducing cardiovascular complications with clinical benefit for patients in controlled clinical trials with progressively decreasing LDL-cholesterol levels. The most ambitious goals have been achieved with statin monotherapy (JUPITER [Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin]), combined statin/ezetimibe therapy (IMPROVE-IT), and the recent trials with PCSK9 inhibitors (Fourier and ODYSSEY Outcomes).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/25299123/00000036000000S1/v1_202502240704/S2529912325000105/v1_202502240704/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)