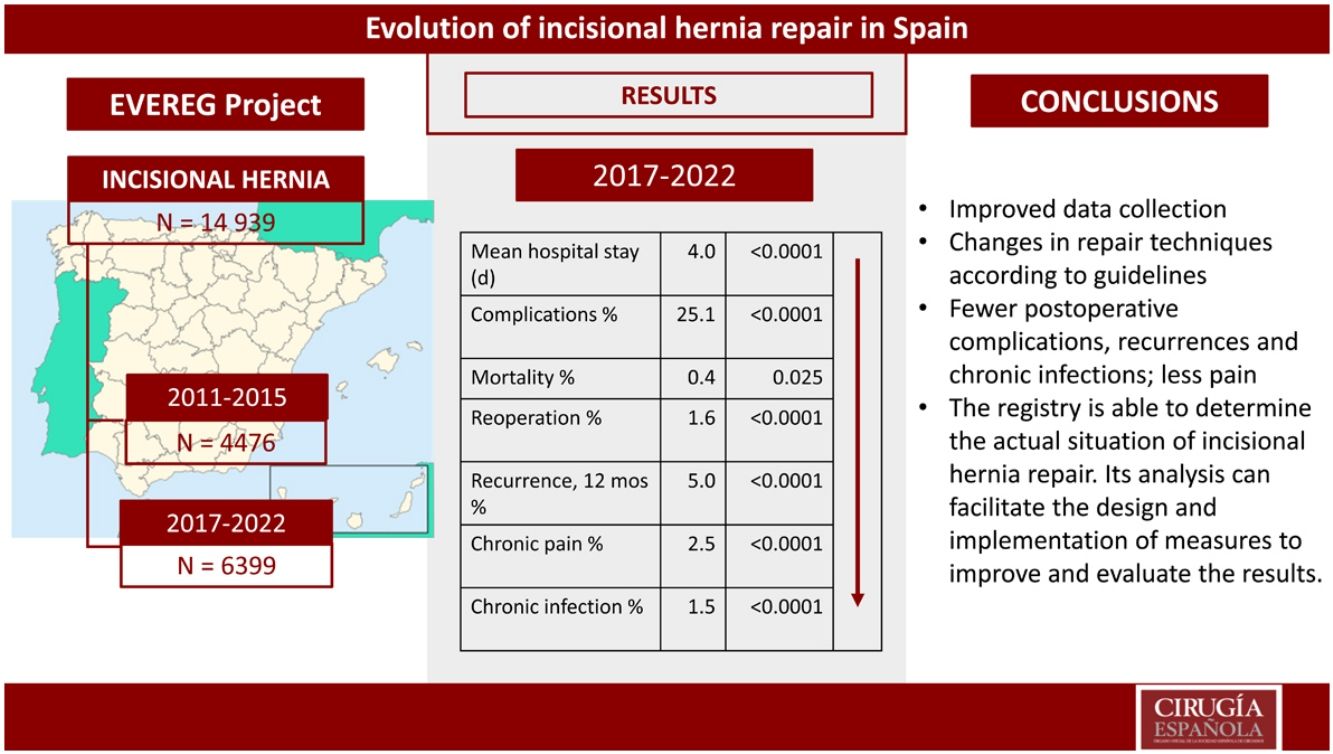

The aim of this study was to assess the utility of the EVEREG registry in evaluating the evolution of surgical treatment for incisional hernia and its outcomes in Spain by comparing data from 2 study periods.

MethodsA retrospective comparative analysis of hernia surgeries performed between 2011 and 2015 (first period) and between 2017 and 2022 (second period) was conducted using data collected from the EVEREG registry.

ResultsStatistically significant differences were observed in the second cohort, including: a decrease in minimally invasive procedures (11.7% vs 8.2%; P < .001), an increase in emergency surgeries for males (31.7% vs 41.2%; P = .017), an increase in trocar hernia repairs (16% vs 26.2%; P < .0001), a reduction in suture repairs (2.8% vs 1.5%; P < .0001), and an increase in retromuscular techniques (36.4% vs 52.4%; P < .001) in open surgery with mesh.

In elective surgery, there was a decrease in the average length of stay (4.9 vs 3.8 days; P < .0001), the percentage of complications (27.9% vs 24.0%; P < .0001), reoperations (3.5% vs 1.4%; P < .0001), and mortality (0.6% vs 0.2%; P = .002).

Long-term outcomes included a decrease in recurrences after 12 months (20.7% vs 14.5%; P < .0001) and in chronic pain (13.7% vs 2.5%; P < .0001) and chronic infections (9.1% vs 14.5%; P < .0001) after 6 months.

ConclusionIn recent years, there has been a significant improvement in the outcomes of incisional hernia treatment. The registry serves as a fundamental tool for assessing the evolution of hernia treatment and enables the identification of key areas for improvement and the evaluation of treatment outcomes.

El objetivo del estudio fue comprobar la utilidad del registro EVEREG para evaluar la evolución del tratamiento quirúrgico de la hernia incisional y sus resultados en España, comparando los datos de dos períodos de estudio.

MétodosAnálisis retrospectivo comparativo de las hernias operadas entre 2011 y 2015 (primer período) y entre 2017 y 2022 (segundo período) usando los datos recopilados en el registro EVEREG.

ResultadosSe detectaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la cohorte más reciente en: disminución de abordaje mínimamente invasivo (11,7% vs. 8,2%; P < 0,001); incremento de varones intervenidos de urgencia (31,7% vs. 41,2%; P = 0,017); incremento de las reparaciones de hernias de trócar (16% vs. 26,2 %; P < 0,0001); reducción de reparaciones sin malla (2,8% vs. 1,5%; P < 0,0001); aumento de técnicas retromusculares (36,4% vs. 52,4%; P < 0,001) en la cirugía abierta con malla.

En la cirugía electiva disminuyó la estancia media (4,9 vs. 3,8 días; P < 0,0001), el porcentaje de complicaciones (27,9 % vs. 24,0%; P < 0,0001), reintervenciones (3,5% vs. 1,4%; P < 0,0001) y mortalidad (0,6% vs. 0,2%; P = 0,002).

A largo plazo se produjo una disminución de recurrencias a los 12 meses (20,7% vs. 14,5%; P < 0,0001) y del dolor (13,7% vs. 2,5%; P < 0,0001) e infección crónicos (9,1% vs. 14,5%; P < 0,0001) a los seis meses.

ConclusiónSe ha producido una importante mejora de los resultados en el tratamiento de la hernia incisional en los últimos años. El registro es una herramienta fundamental para comprobar la evolución del tratamiento de las hernias y permite discernir los principales puntos para implementar mejoras y evaluar los resultados de estas.

Clinical registries are a paradigmatic example of the relevance of using specific, unified, open, global databases to accurately understand real-world evidence in the treatment of diseases.1,2

Abdominal wall records have provided data that have led to relevant advances in understanding surgical results, facilitating the introduction of changes in the treatment guidelines of this highly prevalent pathology.3–6

The EVEREG Incisional Hernia Registry began in 2011, and the analysis of its data has allowed us to study the characteristics of patients and their surgeries,7 risk factors for the appearance of complications and recurrences,8 and results after specific repair procedures.9–11 The reliability of the data has been confirmed by audit.12

The objectives of this study are to evaluate the results of surgical treatment of incisional hernia (IH) in Spain, comparing 2 periods of patient data collection (2011–2015 and 2017–2022) in the EVEREG registry, and to verify the usefulness of the registry to evaluate the situation over time.

MethodsThe EVEREG registry began in 2011, initiated by the Abdominal Wall and Sutures Division of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC), being one of the oldest in Europe.

Currently, it has 4 data collection categories: Incisional Hernia, Primary Ventral Hernia, Inguinal Hernia, and Prophylaxis. A total of 201 hospitals throughout the country participate in the registry, representing 38% of the hospitals in the Spanish National Health System. By September 2023, the IH category had accumulated a total of 14 939 cases (https://www.evereg.es/).

Descriptions of the data collection and storage systems have been previously published.8,9 In short, data is collected prospectively and anonymously in an online database and stored on an external server. The data collected include: patient characteristics; hernia type and surgical approach; complications; and follow-up variables one month, 6 months, one year and 2 years after all IH operated on at the participating medical centers. Global data are only accessible by the surgeons in charge of the national registry.

For this study, we analyzed the data of the interventions carried out between 2017 and 2022 (N = 6399) at 133 centers and compared these to the cohort of patients operated on between 2011 and 2015, published in 2016 (N = 4476)8 using the same inclusion/exclusion criteria. In the second cohort, records with no follow-up during the first 30 days after surgery (N = 189) were excluded from postoperative analysis. Likewise, those without complete postoperative follow-up data at 6 months (N = 3023), one year (N = 3867) and 2 years (N = 4812) were excluded from the long-term analysis. The results were compared following the same format as the previous study.

Statistical analysisThe data were exported to the SPSS v28.0 (IBM Inc., Rochester, MN, USA) statistical analysis package. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative variables are reported as proportions. Qualitative variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or the Fisher test when necessary, as well as the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney test for quantitative variables. The normality of the distribution of the quantitative variables was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Statistical significance was established at P < .05.

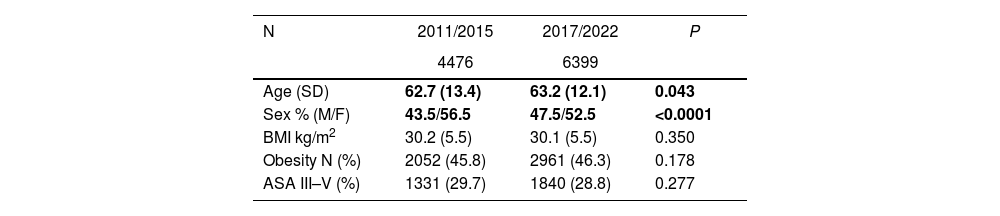

ResultsThe sociodemographic characteristics of both cohorts and their comparison are shown in Table 1. Two data showed statistically significant changes, with slight increases observed in both the average age and the percentage of male patients operated on in the second period.

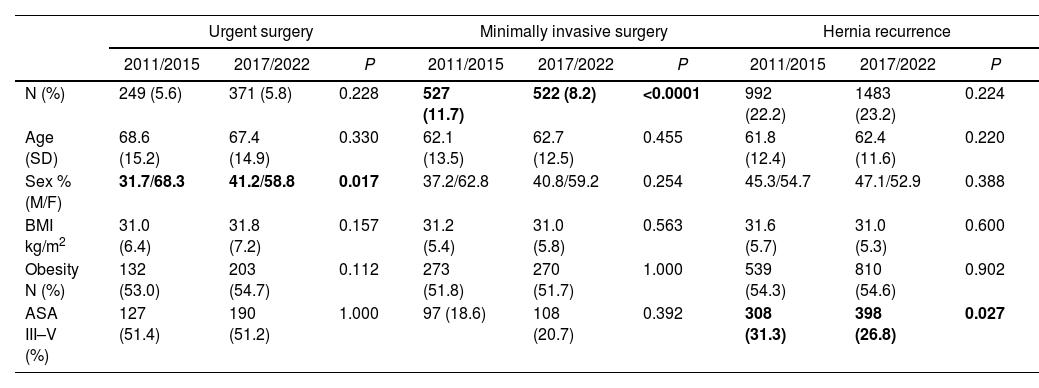

A comparison of the surgery type, approach and hernia type is shown in Table 2. Three data demonstrate significant differences: a higher percentage of men undergoing emergency surgery, a lower percentage of procedures performed using minimally invasive surgery (MIS), and a lower percentage of patients with high anesthetic risk undergoing surgery for recurrent IH.

Comparison by type of procedure, approach and hernia.

| Urgent surgery | Minimally invasive surgery | Hernia recurrence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P | 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P | 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P | |

| N (%) | 249 (5.6) | 371 (5.8) | 0.228 | 527 (11.7) | 522 (8.2) | <0.0001 | 992 (22.2) | 1483 (23.2) | 0.224 |

| Age (SD) | 68.6 (15.2) | 67.4 (14.9) | 0.330 | 62.1 (13.5) | 62.7 (12.5) | 0.455 | 61.8 (12.4) | 62.4 (11.6) | 0.220 |

| Sex % (M/F) | 31.7/68.3 | 41.2/58.8 | 0.017 | 37.2/62.8 | 40.8/59.2 | 0.254 | 45.3/54.7 | 47.1/52.9 | 0.388 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 31.0 (6.4) | 31.8 (7.2) | 0.157 | 31.2 (5.4) | 31.0 (5.8) | 0.563 | 31.6 (5.7) | 31.0 (5.3) | 0.600 |

| Obesity N (%) | 132 (53.0) | 203 (54.7) | 0.112 | 273 (51.8) | 270 (51.7) | 1.000 | 539 (54.3) | 810 (54.6) | 0.902 |

| ASA III–V (%) | 127 (51.4) | 190 (51.2) | 1.000 | 97 (18.6) | 108 (20.7) | 0.392 | 308 (31.3) | 398 (26.8) | 0.027 |

Regarding the surgery performed, in the 2017–2022 period, 5.3% of patients required intestinal resection. In elective surgery, this was more frequent than in the initial cohort (1.1% vs 4.5%; P < .0001), with no significant changes in urgent surgery (15.3% vs 19.8%; P = .383).

When comparing the locations of the hernias, a decrease was found in midline hernias in the 2017–2022 cohort (66.9% vs 57.6%; P < .0001) along with an increase in midline trocar hernia repairs (16% vs 26.2%; P < .0001) and parastomal hernias (3.9% vs 5.1%; P = .003).

Hernias with a transverse diameter of 10–15 cm were less frequent in the most recent cohort (12.7% vs 11.2%; P = 0.02), with no differences observed in hernias with a diameter greater than 15 cm (5.8% vs 5.5%; P = .49).

Mesh repairs remained predominant, and there has been a significant reduction in primary repairs without mesh (2.8% vs 1.5%; P < .0001).

When we focused on open surgical procedures in which a mesh was applied, currently the most common repair is mesh placement in a retromuscular or preperitoneal position (36.4% vs 52.4%; P < .001). Two prostheses were implanted in different planes in a higher percentage of cases (8.9% vs 13.1%; P < .0001), and component separation was performed in similar percentages in both groups (16.3% vs 16.7%; P = .82). In the first group, however, only anterior component separation was used, whereas posterior separation of components predominated in subsequent cases (59.8%).

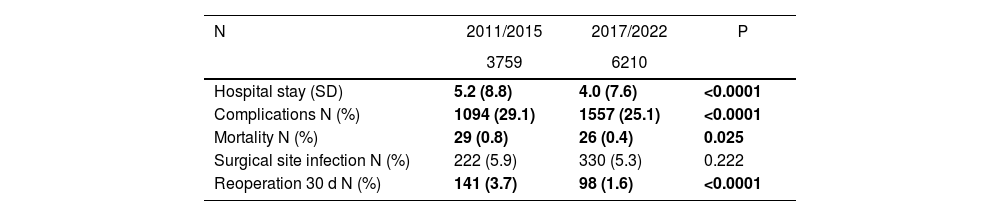

Regarding the postoperative results (Table 3), we observed significant reductions in the average hospital stay, percentage of complications, mortality and reinterventions.

Comparison of postoperative results.

| N | 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3759 | 6210 | ||

| Hospital stay (SD) | 5.2 (8.8) | 4.0 (7.6) | <0.0001 |

| Complications N (%) | 1094 (29.1) | 1557 (25.1) | <0.0001 |

| Mortality N (%) | 29 (0.8) | 26 (0.4) | 0.025 |

| Surgical site infection N (%) | 222 (5.9) | 330 (5.3) | 0.222 |

| Reoperation 30 d N (%) | 141 (3.7) | 98 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

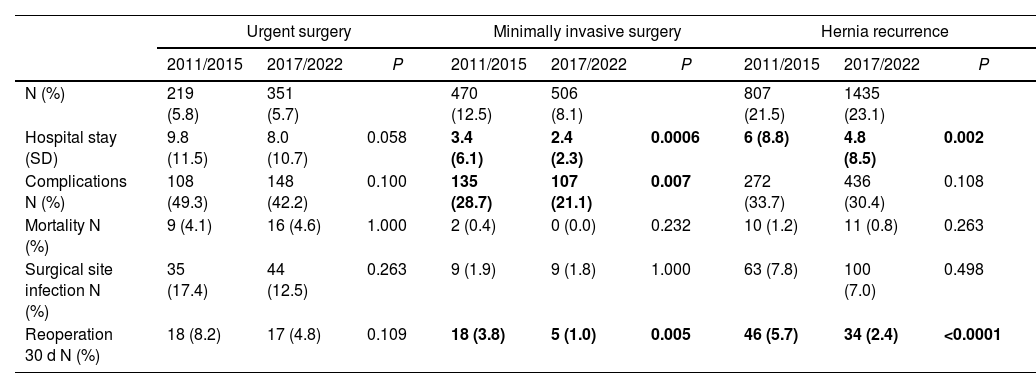

The comparison of postoperative results by intervention type, approach and previous hernia repair (Table 4) did not detect changes after urgent surgery. MIS and surgery after previous repair showed a clear decrease in the mean hospital stay and in the percentage of reoperations, while the frequency of complications was significantly lower in minimally invasive surgery.

Postoperative results according to type of procedure, approach and previous repair.

| Urgent surgery | Minimally invasive surgery | Hernia recurrence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P | 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P | 2011/2015 | 2017/2022 | P | |

| N (%) | 219 (5.8) | 351 (5.7) | 470 (12.5) | 506 (8.1) | 807 (21.5) | 1435 (23.1) | |||

| Hospital stay (SD) | 9.8 (11.5) | 8.0 (10.7) | 0.058 | 3.4 (6.1) | 2.4 (2.3) | 0.0006 | 6 (8.8) | 4.8 (8.5) | 0.002 |

| Complications N (%) | 108 (49.3) | 148 (42.2) | 0.100 | 135 (28.7) | 107 (21.1) | 0.007 | 272 (33.7) | 436 (30.4) | 0.108 |

| Mortality N (%) | 9 (4.1) | 16 (4.6) | 1.000 | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.232 | 10 (1.2) | 11 (0.8) | 0.263 |

| Surgical site infection N (%) | 35 (17.4) | 44 (12.5) | 0.263 | 9 (1.9) | 9 (1.8) | 1.000 | 63 (7.8) | 100 (7.0) | 0.498 |

| Reoperation 30 d N (%) | 18 (8.2) | 17 (4.8) | 0.109 | 18 (3.8) | 5 (1.0) | 0.005 | 46 (5.7) | 34 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

In elective surgery, there were significant differences in: mean stay (4.9 vs. 3.8; P < .0001), complications (27.9% vs 24.0%; P < .0001), reoperations (3.5% vs 1.4%; P < .0001) and mortality (0.6% vs 0.2%; P = .002). These differences also occurred in open surgery (mean stay 5.5 vs 4.2; P < .0001; complications 29.2 vs 25.4; P = .0003; mortality 0.8% vs 0.5%; P = .03; and reoperations 3.7% vs 1.6%; P < .0001) and in primary repair (mean stay 5 vs 3.8; P < .0001; complications 27.8% vs 23.5%; P < .0001; mortality 0.6% vs 0.3%; P = .05; and reoperations 3.2% vs 1.3%; P < .0001). The only parameter that did not experience significant changes under any circumstance was wound infection.

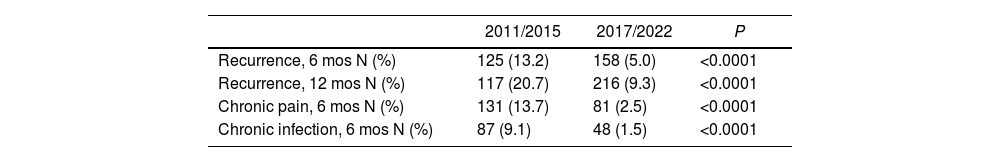

The comparison of long-term results, after a median follow-up of 15.4 months (CI 12.3–22.5) in the first period and 17.5 (CI 12.3–24.6) in the second, demonstrated a significant decrease in recurrences in the second study period (20.7% vs 14.5%; P < .0001).

The comparative results recorded 6 months and 12 months after the operation (recurrences, pain and chronic infection) are shown in Table 5. Again, all the parameters compared demonstrated a significant decrease in the second cohort. However, the cumulative incidence of recurrence in patients with a 2-year follow-up rose progressively to 23%.

DiscussionOur comparative analysis of the data from the 2 study periods shows that changes have occurred in the surgical treatment of IH in recent years, which have resulted in significant improvements in both short- and long-term complications.

Likewise, we have observed improved data collection in the registry itself. In the initial cohort, only 24.3% and 17.9% of cases had follow-up times of more than 6 months and one year, respectively. In the current cohort, these follow-up times have increased to 49.8% (6 months) and 36.6% (12 months). In our opinion, this means that the measures taken to improve data collection since the initial period have been effective even though we have not made progress in terms of incentivizing data collection across our national healthcare system.

The analysis of sociodemographic data has shown no significant changes in the characteristics of patients undergoing IH repair surgery. There is a continued predominance of patients who are female (although the percentage of men is growing), aged over 60 years, obese, and present a high frequency of associated pathology. In urgent surgery, patients continue to have a higher risk profile. This datum should make us reflect on the effective implementation of prehabilitation protocols in these patients and the use of preventive measures in the initial surgery.

One interesting observation is that, as midline laparotomy hernia repairs have decreased, trocar hernias have increased significantly. This increase seems to be related to the greater frequency of use of the laparoscopic approach, and the importance of preventing hernias in these cases.

As for the surgical approach, not only has the use of MIS not increased, but instead it has decreased significantly. It is expected that the foreseeable increase in the use of robotic surgery will lead to an increase in cases and improved overall results of IH treatment, as previously demonstrated by other series.

Most operations are still performed as open procedures, but relevant changes have come about in this approach and its results. IH repair without mesh is now an exception, in line with studies that demonstrate the safety of its use13,14 even in contaminated areas.15 There has been an inversion in terms of the mesh position, with the retromuscular/preperitoneal position becoming predominant, as recommended by prospective studies16 and clinical guidelines.17

Similarly, the positive results reported in studies using 2 pieces of prosthetic mesh for complex repairs18 or subsequent component separation19 have led to their increased use in the cases recorded in the second study period.

Postoperative data demonstrate that there has been a notable improvement in outcomes since the initial period of the registry. We have observed reductions in the average length of stay, complications, mortality and the need for reoperation within the first thirty days. However, a worrying percentage of wound infection persists (around 5%), which has not improved significantly under any of the circumstances analyzed. MIS was the only situation that presented, in both cohorts, a lower frequency of wound infection (2%). Therefore, new studies are necessary aimed at preventing/reducing wound infection and planning measures to increase the use of MIS in IH and abdominal wall surgery, as previously suggested.20

This improvement occurred in elective surgery, the open approach, MIS and recurrence. No changes were observed in urgent surgery. Consequently, it is necessary to better analyze the causes and implement improvements in emergency care, as other studies have already proposed.8,21

Long-term complication rates have also improved significantly, as the 6- and 12-month recurrence rates have been reduced by half. It is likely that the higher follow-up percentages in the second cohort had an influence, but the changes introduced in the surgical technique and the decrease in complications must have also been relevant. However, when we evaluated the patients with 2-year follow-ups, the frequency of recurrence increased progressively (23%). Therefore, given the low incidence of both chronic pain and infection, as we considered in our initial analysis of the registry, the main objective continues to be the reduction in the recurrence rate.

As previously indicated in other publications by other authors, the strengths of our study are related to the strengths of the registry: meticulous data collection, and the high number of patients and participating centers. Additionally, we should emphasize the reliability of the data, as demonstrated in a recent audit.12

The main weakness is the long-term follow-up, for which only 49.8% of cases had data available 6 months after surgery, 39.6% at one year post-op, and 21.8% at 2 years post-op, even though follow-up times had improved significantly. This limited our data analysis on long-term complications.

In conclusion, data collection in the registry has experienced a noticeable improvement in the second period analyzed. Changes have been made to surgical techniques for open IH repair that better align with the recommendations of the European Hernia Society and scientific studies. Significant reductions have been achieved in the average length of stay, complications, mortality rate, and the number of reoperations. Likewise, improvements have been observed in the incidence of recurrences, chronic pain and infection. Measures should be adopted to increase the use of MIS and to reduce wound infection and recurrence rates. The registry is a fundamental tool to determine the actual situation of IH repair, and the analysis of its data identifies the main points on which to focus improvement measures and to evaluate the evolution of the results over time.

FinancingB. Braun.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Silvia Martínez and Xavier Masramón. SAIL (Research and Logistics Advisory Service).