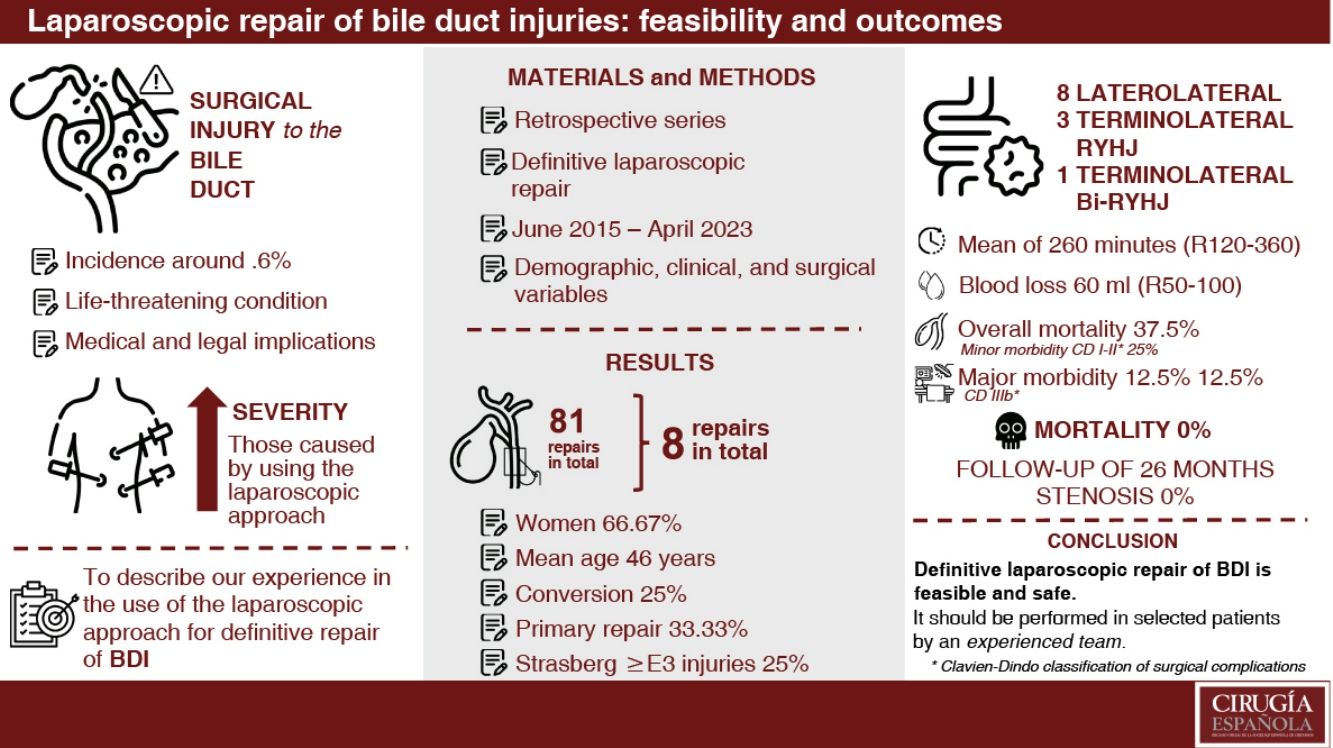

Bile duct injuries (BDI) following laparoscopic cholecystectomy occurs in approximately 0.6% of the cases, often being more severe and complex. Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (RYHJ) is considered the optimal therapeutic option, with success rates ranging from 75% to 98%. Several series have demonstrated the advancements of the laparoscopic approach for resolving this condition. The objective of this study is to describe our experience in the laparoscopic repair of BDI.

MethodsA retrospective, descriptive study was conducted, including patients who underwent laparoscopic repair after BDI. Demographic, clinical, surgical, and postoperative variables were analysed using descriptive statistical analyses.

ResultsEight patients with BDI underwent laparoscopic repair (out of 81 surgically repaired patients). Women comprised 75% of the sample. A complete laparoscopic repair was achieved in 75% (6) of cases. The mean age was 40.8 ± 16.61 years (range 19−65). Injuries at or above the confluence (Strasberg-Bismuth ≥ E3) occurred in 25% of cases (2). Primary repair was performed in two cases. Half of the cases underwent a Hepp-Couinaud laterolateral RYHJ, while three patients received a terminolateral RYHJ, and one underwent a bi-terminolateral RYH. The mean operative time was 260 min (range 120−360). Overall morbidity was 37.5% (3 cases): two minor complications (bile leak grade A and drainage-related bleeding) and one major complication (bile leak grade C). No mortality was recorded. The maximum follow-up period reached 26 months (range 6–26).

ConclusionsOur study demonstrates the feasibility of laparoscopic RYHJ in a selected group of patients, offering the benefits of a minimally invasive approach.

Las lesiones quirúrgicas de la vía biliar (LQVB) posteriores a la colecistectomía videolaparoscópica tienen una incidencia del 0,6% aproximadamente, siendo generalmente más graves y complejas. La hepaticoyeyunoanastomosis en Y de Roux (HYA) es la mejor opción terapéutica (tasas de éxito entre 75–98%). Algunas series demostraron factible el abordaje laparoscópico en la resolución de esta patología. El objetivo es describir nuestra experiencia en la reparación laparoscópica de las LQVB.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo, descriptivo. Se incluyeron pacientes sometidos a reparación laparoscópica posterior a LQVB. Se analizaron variables demográficas, clínicas, quirúrgicas y postoperatorias. Se aplicaron análisis estadísticos descriptivos.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 92 pacientes con LQVB; 81 se sometieron a reparación quirúrgica, ocho fueron candidatos a HYA laparoscópica (aplicabilidad 9,88%). En el 75% (6) se logró una reparación laparoscópica completa. La mayoría eran mujeres (75%). Edad promedio de 40,8 ± 16,61 años (rango 19−65). Las lesiones Strasberg-Bismuth ≥ E3 afectaron al 25% (2). En la mitad se realizó una HYA laterolateral según la técnica de Hepp-Couinaud; tres pacientes recibieron una HYA terminolateral y otro una bi-HYA terminolateral en Y de Roux. Tiempo operatorio promedio de 260 minutos (rango 120−360). La morbilidad global fue del 37,5% (3 casos): dos complicaciones menores (bilirragia grado A y hemorragia por drenajes) y una mayor (bilirragia grado C). No se registró mortalidad. El seguimiento máximo fue de 26 meses (rango 6–26).

ConclusionesNuestro estudio muestra que en un grupo seleccionado de pacientes, la HYA laparoscópica es factible, con los beneficios de un abordaje miniinvasivo.

The incidence of bile duct injuries (BDI) after videolaparoscopic cholecystectomy varies between .3% and .8%.1–3 BDI occurring during videolaparoscopic cholecystectomy have been shown to be more severe and complex due to the height of the injury and potential associated vascular injury. Of the surgical options, a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (RYHJ) is the best alternative with success rates between 75% and 98% in specialist centres with the means and trained surgeons.4,5

The treatment of BDI has improved over time. The laparoscopic approach has demonstrated the already known benefits of the mini-invasive approach as both temporary and definitive treatment, and has been described in case series as safe and feasible.6–12

The objective of this study is to describe our experience with definitive laparoscopic surgical repair of BDI.

MethodsA retrospective, descriptive study of a prospective database. All patients who underwent definitive laparoscopic BDI repair between June 2015 and April 2023 were included in the sample. The variables analysed were demographic (age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities), clinical, and surgical (indication and details of cholecystectomy, type and mechanism of the lesion, pre- and postoperative studies, therapeutic interventions, time to repair, and details of the RYHJ).

We classified BDI as simple and complex. Those with a complex injury were excluded from the series.25 Patients were included if there was no active infection (cholangitis, biloma, or choleperitoneum) and/or other complication. Antibiotic treatment was given when necessary. All patients were preoperatively evaluated with triple-phase multislice computed tomography (CT) to rule out abscesses and collections and to evaluate associated vascular injury. Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreaticography and/or cholangiography through drains (if any) was performed to evaluate and classify the injury as proposed by Strasberg.13 On completion of the preoperative studies, we used a laparoscopic approach in all patients.

The clinical status of the patients was evaluated and optimised in a multidisciplinary team of nutritionists, infectologists, endoscopists, and anaesthesiologists.

According to study findings, the general condition of the patients, and the time of injury, collections were drained if necessary and the intervention deferred until the local and systemic conditions were adequate. These repairs were classified as early (up to 72 h after injury) or late (after 6 weeks).24

Statistical analysisWe performed a retrospective analysis with MedCalc® v20.115 of a prospective database created in Microsoft® Excel 2019 v16.56. Descriptive statistics were applied as needed.

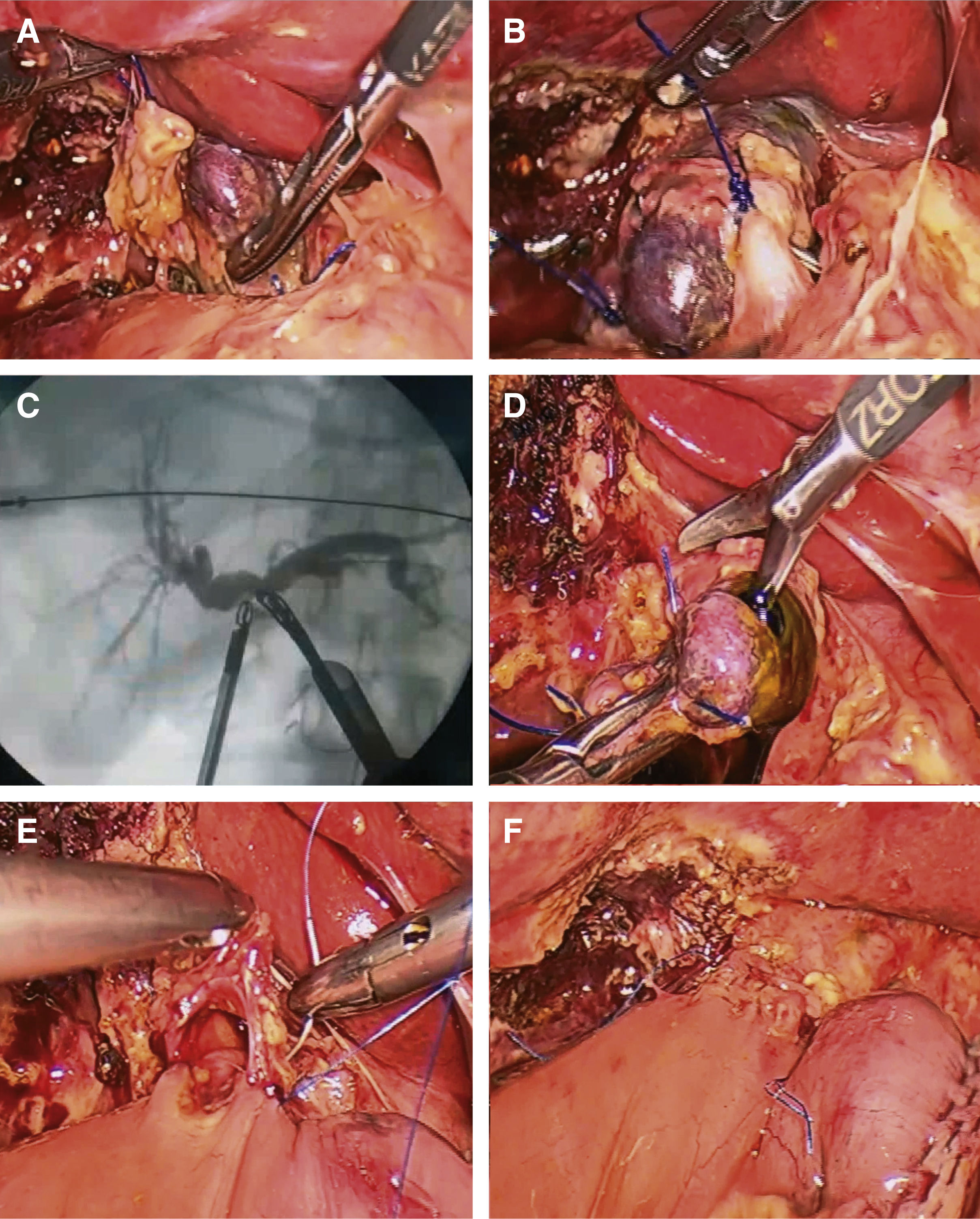

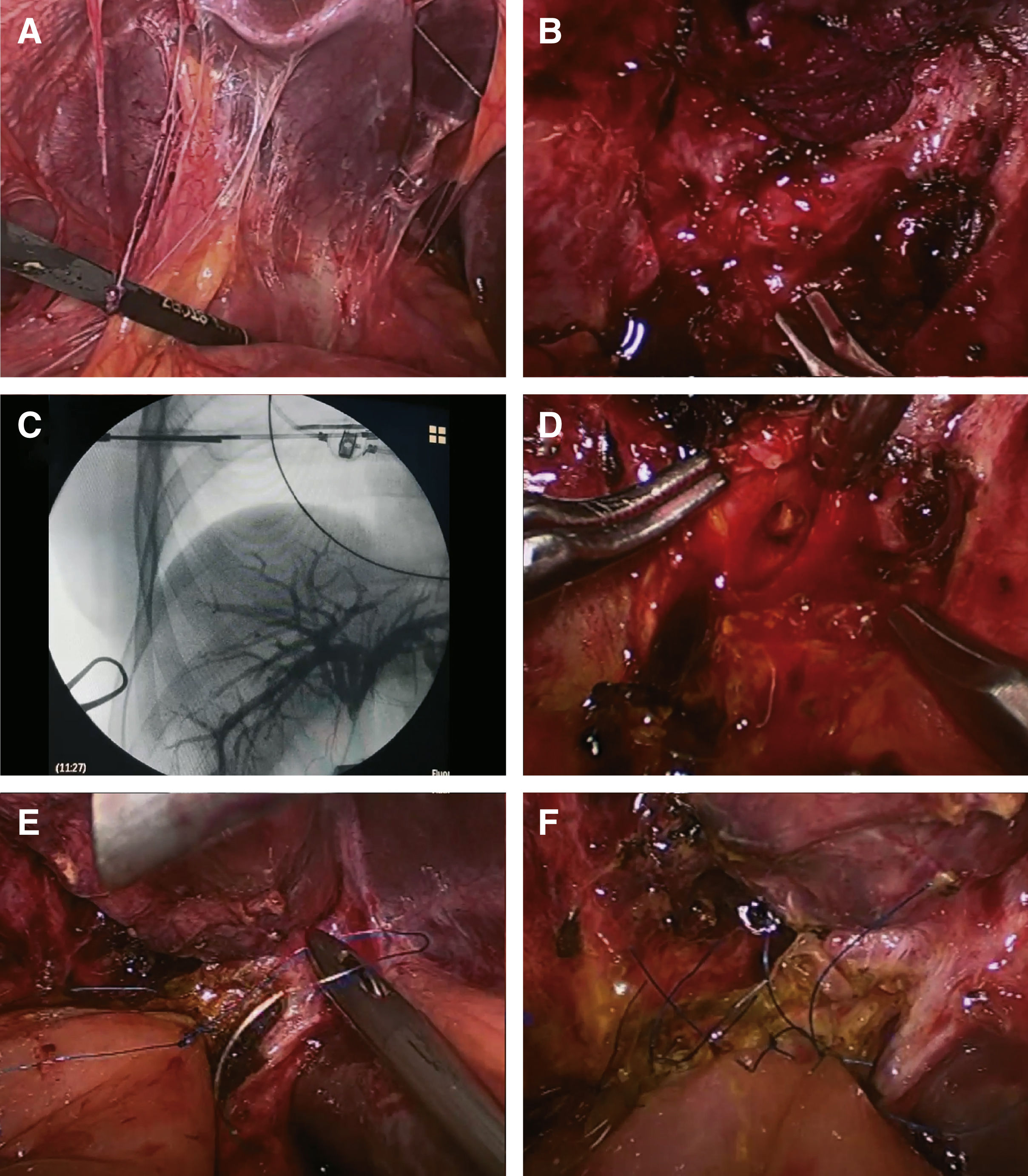

Surgical techniqueThe laparoscopic approach was used in the supine position with the surgeon on the patient's left. A 10 mm umbilical port, a 10 mm epigastric port, two 5 mm accessories in the hypochondrium and right flank, and a fifth trocar were used as needed. Intraoperative cholangiography was performed in all surgeries to identify all segments of the intrahepatic biliary tree. RYHJ was the elective definitive repair surgery. The repair of choice was a terminolateral RYHJ (Fig. 1) for early repairs, and for late repairs a laterolateral RYHJ according to the Hepp-Couinaud technique (Fig. 2). Routine bile samples were taken. These were sent for culture and antibiotic therapy was selected according to the germ isolated.37 The suture, unlike with the conventional approach, starts from the right to the left of the patient. The suture material used was 5/0 or 6/0 non-absorbable monofilament, continuous on the posterior aspect and separate stitches or continuous suture on the anterior aspect depending on the diameter of the anastomosis. The Roux-en-Y was created entirely laparoscopically using endoscopic mechanical sutures, ascending the biliary loop via the retrocolic paraduodenal approach.

Early repair of BDI, terminolateral Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy: (A) Ligation and sectioning of the distal portion of the common bile duct. (B) Distal end of the main bile duct ligated and sectioned. (C) Intraoperative cholangiography with Olsen forceps showing integrity of the intrahepatic bile duct. (D) Section and trimming of the proximal edge of the common bile duct to guarantee correct irrigation of the biliary edge of the anastomosis. (E) Creation of posterior continuous suture using non-absorbable 6/0 monofilament suture. (F) Anastomosis completed.

Late repair of BDI, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy according to Hepp-Couinaud: (A) Adhesions associated with surgical history. (B) Dissection of the hilar plate with blunt manoeuvres and scissors. (C) Intraoperative cholangiography by 30G needle puncture showing integrity of the intrahepatic bile duct. (D) Opening of the anterior aspect of the common hepatic duct with extension to the left according to the Hepp-Couinaud technique. (E) Creation of posterior continuous suture finished with non-absorbable 5/0 monofilament suture. (F) Anastomosis finished with separate stitches in the anterior aspect.

Ninety-two patients with BDI were assessed, of whom 81 underwent surgical repair. Of these, eight patients were indicated for laparoscopic RYHJ (applicability 9.88%). Of these 8 patients, 75% (6) could be operated completely laparoscopically. BDI was caused laparoscopically in 7 patients (87.5%) and when converted in the remaining patient. Seventy-five per cent (6) were women. The mean age was 40.8 ± 16.61 years (range 19−65). None of the patients had a surgical history prior to cholecystectomy. The rest of the general and demographic variables are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients with BDI repaired with LBB.

| Characteristics of patients with BDI | Early repairn = 2 (< 72 h) | Late repairn = 6 (≥ 72 h) |

|---|---|---|

| Agea | 45 (41−48) | 39.5 (19−65) |

| Female (%) | 2 (100) | 4 (66.67) |

| Male (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.33) |

| ASA classification ≥3 | 0 (0) | 2 (33.33) |

| Body mass index | ||

| Low weight (<18.49) | 0 | 1 (16.67) |

| Normal (18.5−24.9) | 2 (100) | 2 (33.33) |

| Overweight (25−29.9) | 0 | 1 (16.67) |

| Grade I obesity I (30−34.9) | 0 | 1 (16.67) |

| Grade II obesity (35−39.9) | 0 | 1 (16.67) |

| Cholecystectomy approach | ||

| Laparoscope (%) | 2 (100) | 5 (83.33) |

| Conversion (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| BDI classification (Strasberg) | ||

| E1 (%) | 1 (50) | 1 (16.67) |

| E2 (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (66.66) |

| E3 (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| E5 (%) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Indication for cholecystectomy | ||

| Symptomatic gallstones (%) | 2 (100) | 5 (83.33) |

| Acute cholecystitis (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| Mechanism of injury | ||

| Cold section | 2 (100) | 2 (33.33) |

| Clipping and cold section | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

| Thermal | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| Index surgery procedure | ||

| Elective (%) | 2 (100) | 5 (83.33) |

| Emergency (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| BDI identified during cholecystectomy (%) | 2 (100) | 1 (16.67) |

BID surgical bile duct injury, LBB laparoscopic biliary bypass.

The average time from BDI and diagnosis was 2.13 days (range 0−5 days). In 3 patients the injury was diagnosed intraoperatively. Of these, 2 underwent early repair and drains were placed in the remaining patient who was later referred to our institution. In the other 5 patients the lesion was diagnosed postoperatively. In these patients, the clinical presentation included fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, and bile leakage through surgical drains (Table 2). These patients required some type of procedure after the BDI: percutaneous biloma drainage, percutaneous bile duct drainage due to jaundice, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to diagnose the injury prior to repair (the latter 2 procedures were requested by the team performing the procedure prior to referral). No patient had an associated vascular injury on preoperative triple-phase contrast-enhanced CT. The mean time from BDI to videolaparoscopic RYHJ was 119 ± 114.1 days (range 1–316). In 6 patients (75%) the repair was late (later than 6 weeks after injury); in the remaining 2 patients the injury was repaired early. The height of the injury according to the Strasberg-Bismuth classification14 is presented in Table 1. Six occurred below the confluence (E1 and E2), one at the level of the confluence (E3), and one associated with right posterior duct injury (E5).

Variables prior to definitive surgical repair.

| Pre-repair variables | Early repairn = 2 (<72 h) | Late repairn = 6 (≥72 h) |

|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy (%) | 2 (100 | 1 (16.67) |

| Bile leakage through drains (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.33) |

| Jaundice (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.33) |

| Fever and abdominal pain (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.33) |

| ERCP (%) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Percutaneous bile duct drainage (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| Days from cholecystectomy to diagnosis of BDIa | 0 (0) | 3 (0−5) |

| Days from BDI to repaira | 1 (1) | 142 (15−316) |

| Associated vascular injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Table 3 shows the characteristics and operative variables of our repairs. Four patients underwent RYHJ following the Hepp-Couinaud technique. The remaining half underwent 3 terminolateral RYHJ (2 Strasberg E1 and 1 Strasberg E2 injuries) and one terminolateral bi-hepaticojejunostomy (E5 injury with involvement of the right posterior collecting duct). In all cases surgical drains were left in place (usually 2, one posterior and one anterior to the RYHJ).

Operative characteristics and variables.

| Operative characteristics and variables | Early repairn = 2 (<72 h) | Late repairn = 6 (≥72 h) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative blood testsa | ||

| Total bilirubin (RV .20−1.2 mg/dl) | .36 (.33−.38) | 1.14 (.77−2.63) |

| AST (RV 5−34 I/U) | 20 (16−24) | 79.33 (35−195) |

| ALT (RV 0−55 I/U) | 18 (10−26) | 105.5 (29−176) |

| Leukocytes (RV 4−11 K/ul) | 9.56 (8.9−10.22) | 9 (6.67−10.68) |

| Albumin (RV 3.5−5.2 g/dL) | 4 (4−4.1) | 3.79 (3.39−4.27) |

| Prothrombin activity (RV 70%–120%) | 100.5 (92−109) | 84 (56−103) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (RV 40−150 l/U) | 106 (101−112) | 321 (148−552) |

| Laterolateral RYHJ according to Hepp-Couinaud technique (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (66.67) |

| Terminolateral RYHJ (%) | 1 (50) | 2 (33.33) |

| Terminolateral bi-hepaticojejunostomy (%) | 1 (50) | 0 |

| Conversion | 0 | 2 (33.33) |

| Surgical time (minutes)a | 240 (120−360) | 265 (180−360) |

| Operative bleeding (ml)a | 50 (50) | 66.67 (50−100) |

| Postoperative fasting (h)a | 48 (24−72) | 32 (24−48) |

| Hospital stay (days)a | 12 (3−21) | 12.25 (6−17) |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum follow-up (months) | 26 | |

At the beginning of the series there were 2 conversions to open surgery, both due to the impossibility of ascending the biliary loop via the transmesocolonic route and thus create a tension-free biliodigestive anastomosis.

No mortality was reported in our series. The overall morbidity of the series was 37.5% (n = 3). Grade A and C bile leakage occurred in 2 patients. In the first, the bile leakage resolved without intervention and the drains could be removed within 10 days after repair; the second (one of the patients in whom conversion was performed during repair), was re-operated 15 days postoperatively due to abdominal pain and free fluid, where complete dehiscence of the anterior aspect was evident, and required reconstruction of the anterior aspect. The other complicated patient presented with self-limited bleeding from the drains and required a transfusion of 1 unit of sedimented red blood cells.15,16

The mean follow-up of our cohort is 6.32 months (range 2–26). At the time of completion of this study, no strictures have been observed in the anastamoses.

DiscussionThe technical aspects of surgical repair of a BDI are essential for short- and long-term success, namely: well-vascularised bile ducts, non-inflamed tissues, anastomosis of the largest possible diameter between biliary epithelium and intestinal mucosa, and tension-free ensuring complete drainage of all hepatic segments.5,17,29 It should be noted that potential candidates for a laparoscopic approach should be carefully selected, with a body mass index of less than kg/m2, no previous repair attempts and no complex injuries, with good local and systemic conditions for a successful anastomosis. There are currently no consensus guidelines recommending laparoscopic RYHJ.

Our series included 2 patients converted on an intention-to-treat basis, an analysis strategy that helps prevent bias and attempts to better reflect the true utility of the method.

Because the success of the repair depends on the expertise of the treating team, prompt referral to a referral centre is essential, avoiding previous attempts at reconstruction (whether the injury was diagnosed during cholecystectomy or later).

In two cases we were contacted intraoperatively or within 24 h of BDI for definitive repair. As suggested by Brunt et al.,2 we believe this is one of the factors that would explain the good results we have achieved.

As Hepp and Couinaud18 explain, a laterolateral bilioenteric anastomosis makes extensive and potentially dangerous dissection of the common bile duct vasculature unnecessary.

Strasberg and Mercado later demonstrated that this approach is ideal for E3 injuries, but can also be used for E1 and E2 injuries, as well as for the right component of E4 and C5 injuries.5,17 Achieving a wide anastomosis is easier when the opening of the anastomosis is not limited by the diameter of the bile duct. Moreover, creating a high anastomosis allows access to a well-vascularised portion of the biliary tree that is not directly exposed to the inflammatory environment where the BDI occurred.19

We believe that following these principles using the laparoscopic approach (when feasible) should have similar results to conventional repair in addition to the known and proven benefits of minimally invasive surgery.21–24

The stenosis rate ranges from 2.2% and 35.2%,17,20 with the lowest rates found in series in which a latero-lateral anastomosis was used.17 Because this is the reconstruction technique we usually use, we expect to obtain similar results during follow-up.

Despite the relative lack of haptic feedback of laparoscopic surgery, an increasing number of retrospective studies suggest that laparoscopic repair is feasible, safe, and at least non-inferior to open surgery in appropriately selected patients.26

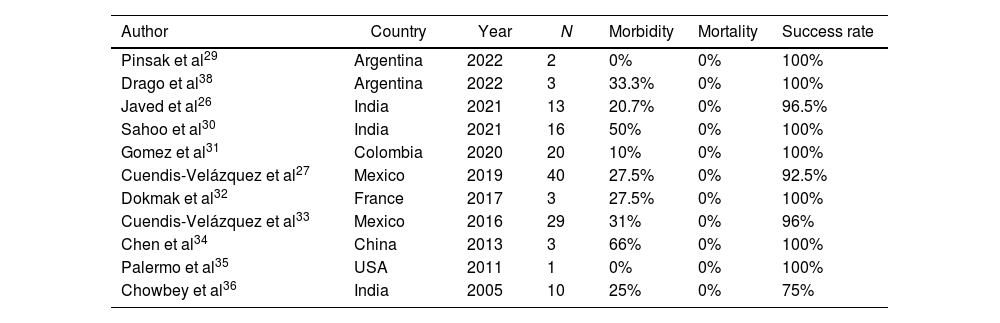

The largest published case series to date of laparoscopic RYHJ for BDI repair has 40 patients (Table 4). It reported an overall morbidity of 27.5% with no mortality. The primary patency rate of the anastomosis during the average 49-month follow-up was 92.5%.27 These results support those published in large series of open repairs in specialist centres.4,28 In a recent study,26,33 laparoscopic bilioenteric anastomoses were compared to 34 patients who received open repairs where significantly lower morbidity (20% vs. 38%), lower intraoperative blood loss (50 ml vs. 200 ml), shorter time to initiation of oral diet (2 vs. 4 days), and shorter hospital stay (6 vs. 8 days) were found in the laparoscopic repair group. There were no significant differences in operative time and overall success rate.

Published series of laparoscopic RYHJ for repair of bile duct injuries.

| Author | Country | Year | N | Morbidity | Mortality | Success rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinsak et al29 | Argentina | 2022 | 2 | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Drago et al38 | Argentina | 2022 | 3 | 33.3% | 0% | 100% |

| Javed et al26 | India | 2021 | 13 | 20.7% | 0% | 96.5% |

| Sahoo et al30 | India | 2021 | 16 | 50% | 0% | 100% |

| Gomez et al31 | Colombia | 2020 | 20 | 10% | 0% | 100% |

| Cuendis-Velázquez et al27 | Mexico | 2019 | 40 | 27.5% | 0% | 92.5% |

| Dokmak et al32 | France | 2017 | 3 | 27.5% | 0% | 100% |

| Cuendis-Velázquez et al33 | Mexico | 2016 | 29 | 31% | 0% | 96% |

| Chen et al34 | China | 2013 | 3 | 66% | 0% | 100% |

| Palermo et al35 | USA | 2011 | 1 | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Chowbey et al36 | India | 2005 | 10 | 25% | 0% | 75% |

We have aimed, as far as possible, for fluid communication with the referring surgical team to obtain all the information about the cholecystectomy and to manage the relationship with patient and family appropriately. This is an initial experience the results of which will have to be analysed in the long term.

This study demonstrates that the laparoscopic approach to BDI repair is feasible. Although our series has a maximum follow-up of 26 months, we believe that the long-term results will be equally satisfactory because we use the same principles as in open repair.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Dr Rosana Pérez Carusi for the final revision of the manuscript and the corrections of style and form.