This study aims to compare the visualization of the cystic duct-common bile duct junction with indocyanine green (ICG) among 3 groups of patients divided according to the difficulty of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

MethodsConducted at a single center, this non-randomized, prospective, observational study encompassed 168 patients who underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy and were assessed with a preoperative risk score to predict difficult cholecystectomies, including clinical factors and radiological findings. Three groups were identified: low, moderate, and high risk. A dose of 0.25 mg of IV ICG was administered during anesthesia induction and the different objectives were evaluated.

ResultsThe visualization of the cystic duct-common bile duct junction was achieved in 28 (100%), 113 (91.1%), and 10 (63%) patients in the low, moderate, and high-risk groups, respectively. The high-risk group had longer total operative time, higher conversion, more complications and longer hospital stay. In the surgeon’s subjective assessment, ICG was considered useful in 36% of the low-risk group, 58% in the moderate-risk group, and 69% in the high-risk group. Additionally, there were no cases where ICG modified the surgeon’s surgical approach in the low-risk group, compared to 11% in the moderate-risk group and 25% in the high-risk group (p < 0.01).

ConclusionsThe results of this study confirm that in the case of difficult cholecystectomies, the visualization of the cystic duct-common bile duct junction is achieved in 63% of cases and prompts a modification of the surgical procedure in one out of four patients.

El objetivo de este estudio es comparar la visualización de la unión cisticocoledocal con verde de indocianina (ICG) entre 3 grupos de pacientes divididos según la dificultad preoperatoria de la colecistectomía laparoscópica electiva.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional, prospectivo no aleatorizado, realizado en un único centro con una cohorte de 168 pacientes sometidos a colecistectomía laparoscópica electiva a quiénes se les calculó un score preoperatorio de riesgo predictivo de colecistectomía difícil publicado por A. Nassar en 2019 que incluyó datos clínicos y radiológicos. Se obtuvieron 3 grupos de riesgo: bajo, moderado y alto riesgo. Se administró 0,25 mg de ICG IV durante la inducción anestésica y se evaluaron los diferentes objetivos.

ResultadosLa visualización de la unión cístico-coledocal se consiguió en 28 (100%), 113 (91,1%) y 10 (63%) pacientes del grupo de bajo, moderado y alto riesgo respectivamente. El grupo de alto riesgo presentó mayor tiempo quirúrgico, conversión a cirugía abierta, complicaciones y estancia hospitalaria. En cuanto a la valoración subjetiva del cirujano, el uso de ICG se consideró útil en el 36% de los pacientes de bajo riesgo, 58% de moderado riesgo y 69% de alto riesgo. Asimismo, modificó la estrategia quirúrgica en 25% de los pacientes del grupo de alto riesgo comparado con 11% del moderado y ninguno del bajo riesgo (p < 0,01).

ConclusionesEn las colecistectomías difíciles la visualización de la unión cisticocoledocal se consigue en el 63% de los casos y condiciona una modificación del procedimiento quirúrgico en uno de cada cuatro pacientes.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for the treatment of cholelithiasis is one of the most common surgical procedures. The most serious complication is iatrogenic bile duct injury (IBDI), with an incidence of .4–1.5%, 5%.1 This can be complex and involve vascular injuries, which increases morbidity, mortality and hospital stay, causing a highly negative impact on the quality of life of patients.2

The critical view of safety (CVS) described by Strasberg in 1995, aims to identify key anatomical structures before occluding and sectioning the cystic duct (CD).3 Although a low rate of IBDI is documented in the literature with the application of this technique, 4–6 there is no evidence to prove that CVS decreases IBDI3,7 Among the procedures to visualise the biliary anatomy is intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), which is very useful in detecting choledocholithiasis during surgery, but it does not significantly reduce the incidence of IBDI and is associated with longer operating time, exposure to radiation and increased costs. Its routine use is therefore not recommended.8–10

In recent years, the use of indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence has been introduced in LC, the purpose of which is to improve the identification of the extrahepatic biliary tree and the cystic-bile duct junction (CBDJ).11,12 ICG is a water-soluble tricarbocyanine molecule that, after intravenous injection, binds to plasma proteins, is metabolised in the liver, and is excreted exclusively in the bile. When excited with near-infrared light, ICG emits a light that allows it to be viewed with fluorescence optics, obtaining an image in real time. Studies have shown that it is safe with a very low rate of complications, and it is only contraindicated in patients allergic to iodine.13,14

The disadvantage is that visualisation decreases when there is an inflammatory process, so in cases of difficult cholecystectomy the use of ICG may be less useful.12

The main objective of this study was to compare the visualisation of the cystic-choledochal junction with ICG in 3 groups divided according to the difficulty of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Secondary objectives were to determine the time required until the cystic duct section; the total operating time; complications; conversion to open surgery, and hospital stay. The utility of ICG, as perceived by the surgeon, was also analysed, together with modification of the surgical strategy in the different patient groups.

Materials and methodsA prospective, non-randomised observational study was conducted, authorised by the Drug Research Ethics Committee (DREC), which included all elective LCs in which fluorescence cholangiography with ICG was used from October 2020 to November 2022 (n = 168).

The operations were performed by the hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgery team made up of 4 surgeons and the rotating resident physicians of that unit. Patients were included both on an outpatient basis and with hospital admission. Patients under 18 years of age, with allergy to iodinated contrast, chronic kidney disease (stages IV and V), liver disease, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and ASA IV were excluded from the study.

Patients were classified according to the preoperative score for predictive risk of difficult cholecystectomy described by A. Nassar in 2019, which is described in Fig. 1.15

Specific questionnaire completed by surgeons when performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; HN: Medical history number; BMI: Body mass index; ICG: Indocyaninegreen; CBDJ: Cystic bile duct junction; MIN: minutes; IBDI: Iatrogenic bile duct injury.

At termination of surgery, the visualisation of the CBDJ (analogue response YES/NO) and the following items: the time measured in minutes from the placement of the first trocar to the section of the cystic duct; the total operating time; the rate of conversion to open surgery; intraoperative complications; whether the surgery was performed by an attending physician or a resident; hospital stay, and postoperative complications at 30 days after surgery, were recorded and expressed according to the Clavien-Dindo classification and the Comprehensive Complication Index.(CCI®)16,17 The subjective assessment of the usefulness of the ICG by the surgeon was recorded using a specific questionnaire shown in Fig. 1. Modification of the surgery was considered as any change during the surgical procedure: the site of the dissection, site of the CD clipping and the performance of retrograde or subtotal cholecystectomy. Finally, the results between each of the groups were compared using the preoperative risk score.

TechniqueICG vials of the “Diagnostic Green®” brand of 25 mg were used, diluted in 100 ml of distilled water, prepared by the pharmacy service in single doses of 1 ml (.25 mg/mL). It was administered intravenously during aesthetic induction, between 20 and 30 min before the dissection of Calot’s triangle. “Olympus®” or “Karl Storz®” fluorescence optics were used for visualisation. The patients were placed in the French position and 4 trocars were used (12 mm umbilical for 30º optics and three 5 mm trocars in the right flank, epigastrium and left flank). A first view was performed with fluorescence optics prior to the dissection of Calot’s triangle to determine if the CBDJ could be visualized (Fig. 2). The hilum of the gallbladder was dissected posteriorly, then anteriorly, dissecting the cystic duct and artery and finally separating the infundibulum from the cystic plate until the critical safety view was obtained. At this point, a second ICG view of the CBDJ was obtained (Fig. 2). The cystic duct was then clipped and sectioned and the cholecystectomy was completed. The final time of surgery was determined when the surgical specimen was removed.

Statistical studyQuantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. Univariate statistical analysis of quantitative variables was performed, with independent groups, using the ANOVA test. Categorical variables were compared using a Chi² test. A value of P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.

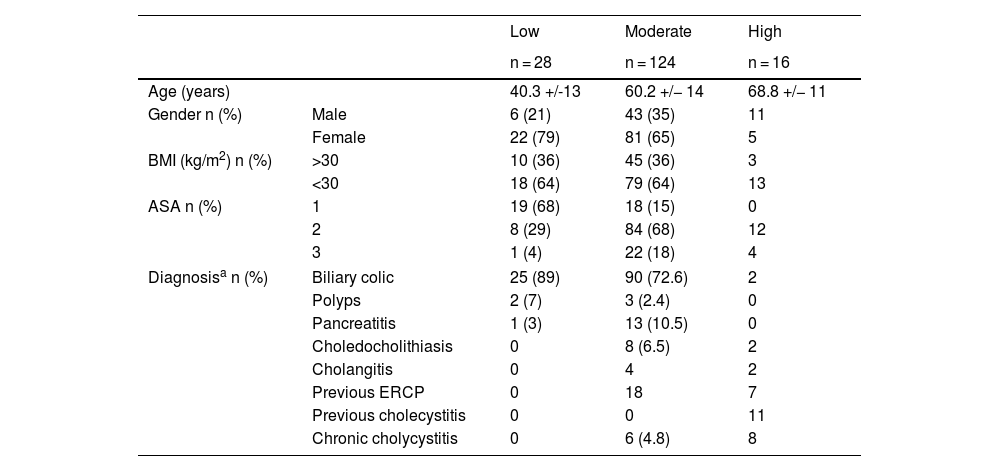

ResultsA total of 168 patients were analysed and classified into the 3 risk groups of surgical difficulty, obtaining 28 patients in the low risk group, 124 in the moderate risk group, and 16 in the high risk group for difficult cholecystectomy. Table 1 contains the characteristics of the patients in each difficulty group.

Patient characteristics according to each difficulty group.

| Low | Moderate | High | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 28 | n = 124 | n = 16 | ||

| Age (years) | 40.3 +/-13 | 60.2 +/− 14 | 68.8 +/− 11 | |

| Gender n (%) | Male | 6 (21) | 43 (35) | 11 |

| Female | 22 (79) | 81 (65) | 5 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) n (%) | >30 | 10 (36) | 45 (36) | 3 |

| <30 | 18 (64) | 79 (64) | 13 | |

| ASA n (%) | 1 | 19 (68) | 18 (15) | 0 |

| 2 | 8 (29) | 84 (68) | 12 | |

| 3 | 1 (4) | 22 (18) | 4 | |

| Diagnosisa n (%) | Biliary colic | 25 (89) | 90 (72.6) | 2 |

| Polyps | 2 (7) | 3 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (3) | 13 (10.5) | 0 | |

| Choledocholithiasis | 0 | 8 (6.5) | 2 | |

| Cholangitis | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Previous ERCP | 0 | 18 | 7 | |

| Previous cholecystitis | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| Chronic cholycystitis | 0 | 6 (4.8) | 8 | |

BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists classification; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

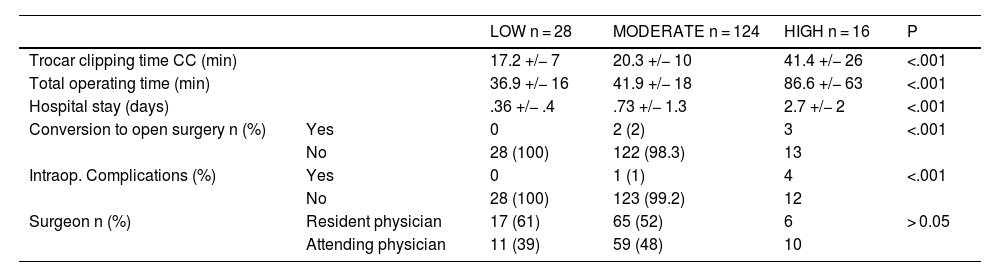

Visualisation of the CBDJ with ICG was achieved in 28 (100%) patients in the low risk group, 113 (91.1%) in the moderate risk group, and 10 (63%) in the high risk group with a statistically significant difference (P < .01). The time between placement of the first trocar and clipping of the CD, the total operating time, the hospital stay, conversion to open surgery, the number of intraoperative complications, and the main surgeon of the surgery are expressed in Table 2.

Results of aspects related to surgery and complications.

| LOW n = 28 | MODERATE n = 124 | HIGH n = 16 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trocar clipping time CC (min) | 17.2 +/− 7 | 20.3 +/− 10 | 41.4 +/− 26 | <.001 | |

| Total operating time (min) | 36.9 +/− 16 | 41.9 +/− 18 | 86.6 +/− 63 | <.001 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | .36 +/− .4 | .73 +/− 1.3 | 2.7 +/− 2 | <.001 | |

| Conversion to open surgery n (%) | Yes | 0 | 2 (2) | 3 | <.001 |

| No | 28 (100) | 122 (98.3) | 13 | ||

| Intraop. Complications (%) | Yes | 0 | 1 (1) | 4 | <.001 |

| No | 28 (100) | 123 (99.2) | 12 | ||

| Surgeon n (%) | Resident physician | 17 (61) | 65 (52) | 6 | > 0.05 |

| Attending physician | 11 (39) | 59 (48) | 10 |

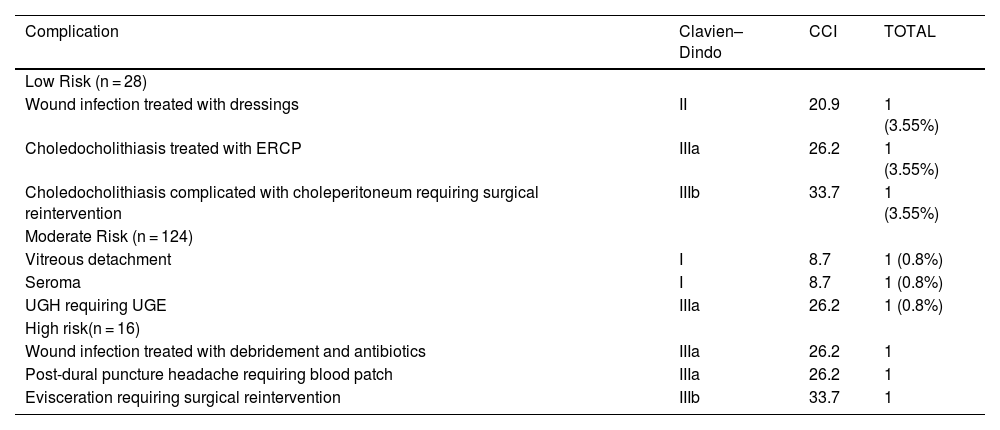

With regards to intraoperative complications, one case of haemorrhage occurred in the moderate-risk group, as well as one intestinal injury and 3 haemorrhages in the high-risk group, all resolved during the same procedure. The complications recorded in the 30 days postoperatively are shown in Table 3. There were no cases of mortality.

Complications within 30 postoperative days.

| Complication | Clavien–Dindo | CCI | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk (n = 28) | |||

| Wound infection treated with dressings | II | 20.9 | 1 (3.55%) |

| Choledocholithiasis treated with ERCP | IIIa | 26.2 | 1 (3.55%) |

| Choledocholithiasis complicated with choleperitoneum requiring surgical reintervention | IIIb | 33.7 | 1 (3.55%) |

| Moderate Risk (n = 124) | |||

| Vitreous detachment | I | 8.7 | 1 (0.8%) |

| Seroma | I | 8.7 | 1 (0.8%) |

| UGH requiring UGE | IIIa | 26.2 | 1 (0.8%) |

| High risk(n = 16) | |||

| Wound infection treated with debridement and antibiotics | IIIa | 26.2 | 1 |

| Post-dural puncture headache requiring blood patch | IIIa | 26.2 | 1 |

| Evisceration requiring surgical reintervention | IIIb | 33.7 | 1 |

UGE: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; UGH: Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CCI: Comprehensive Complication Index.

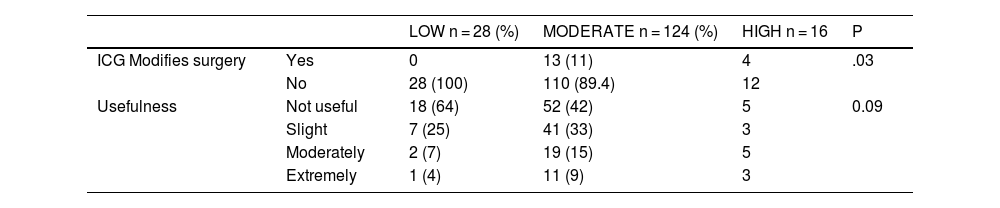

The results of the subjective evaluation of the degree of usefulness of the ICG by the surgeon are shown in Table 4.

Subjective evaluation of the surgeon on the ICG usefulness.

| LOW n = 28 (%) | MODERATE n = 124 (%) | HIGH n = 16 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICG Modifies surgery | Yes | 0 | 13 (11) | 4 | .03 |

| No | 28 (100) | 110 (89.4) | 12 | ||

| Usefulness | Not useful | 18 (64) | 52 (42) | 5 | 0.09 |

| Slight | 7 (25) | 41 (33) | 3 | ||

| Moderately | 2 (7) | 19 (15) | 5 | ||

| Extremely | 1 (4) | 11 (9) | 3 |

ICG: Indocyanine green.

LC is the technique of choice for the treatment of cholelithiasis since it has provided shorter hospital stays and recovery times compared to open cholecystectomy and conservative medical treatment, but without reducing the risk of serious complications such as IBDI.1,18

To minimise IBDI, different techniques have been described for the correct identification of biliary hilum structures such as: Strasberg's CVS11 has been shown to reduce iatrogenic complications, but it is only achieved in 50% of cases, with inflammation and fibrosis of the hepatobiliary triangle being a limiting factor. Techniques such as "fundus first" or subtotal cholecystectomy may be the solution in these cases.19,20 2: intraoperative cholangiography has as its main use the detection of choledocholithiasis during surgery9 and helps to define the biliary anatomy, but it is associated with longer operating time, exposure to radiation, higher cost, the need to canalise the CD and does not allow real-time visualisation.8,21 In addition, its routine use is controversial since it has not achieved a significant decrease in the rate of IBDI; and finally, 3: fluorescence with ICG provides identification of the biliary tract, especially the CBDJ without the need for radiology, with a low cost and technical ease.10,12,22 Likewise, by using the superimposition mode we are able to visualise the bile duct at all times during the dissection, providing greater safety compared to the aforementioned techniques.

There is no standardised form and time of ICG administration 10,23–25 and there is controversy in the literature, as exemplified in the review by Morales-Conde et al.26 Hepatic hyperfluorescence could be a limiting factor for visualisation of the biliary tree, with several studies concluding that ICG administration hours before surgery could improve visualisation by minimising hepatic fluorescence.26–28

Other studies describe correct visualisation of the biliary tree when administered intravenously between 30 min and 2 h prior to surgery.29 Ishizawa et al. administered 2.5 mg of ICG 30 min before the patient entered the operating room and obtained 100% visualisation of the CD, CBDJ and common hepatic duct (CHD).12 Pujol-Cano et al. obtained similar results with a lower dose of .25 mg in anaesthetic induction and were able to visualise the common bile duct in 100% of cases, the CD in 71% of cases and the CBDJ in 84% of cases, without observing hepatic hyperfluorescence in any case.30

Intravesicular administration of ICG has also been described with a visualisation of the biliary tree greater than 75%, which could offer advantages when visualising the hilum of the gallbladder when there is inflammation.31

Our previous experience showed that the highest proportion of visualisation of the CBDJ was obtained in cholecystectomies considered easy by the surgeon and this decreased in cases with an inflammatory process, a situation in which the use of ICG should be more useful. For this reason, this study design classified patients according to a preoperative difficulty score9 to determine the real usefulness of ICG in each of the 3 groups (low, moderate and high).

For this study, we decided to use a dose of .25 mg intravenously administered during anaesthetic induction, demonstrating a visualisation proportion of the CBDJ of 100%, 91.1% and 63% in cholecystectomies of low, moderate and high risk of difficulty respectively, results consistent with previous published experience.15 This form of ICG use is compatible with our centre’s outpatient cholecystectomy programme, since it does not require preparation beyond the time in which the patient is in the surgical area.

In difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomies, the CBDJ was visualised in more than 60% of cases. In our opinion, we recommend the routine use of ICG especially in this group of patients, as it could contribute to reducing IBDI.

The penetration of ICG light sources is 5−10 mm, resulting in a decrease of visualisation of the biliary tract with ICG with tissue inflammation and oedema, as in the case of acute cholecystitis or with increased visceral fat in obese patients, which would explain our results.

Analysis of the study’s secondary objectives showed that in the high-risk group, it took longer to clip the CD and a longer total operating time. There was a higher number of conversions, intraoperative complications, and a longer hospital stay compared to the low- and moderate-risk groups. These results suggest that preoperative assessment of technical difficulty may help predict the procedure complexity and suggest a correct classification of patients into different groups, although this cannot be confirmed because the actual difficulty was not demonstrated according to intraoperative findings.15

The profile of surgeons involved in the different risk groups also showed significant differences. Resident physicians played a more prominent role in the low- and moderate-risk groups, whereas attending surgeons performed most of the surgeries in the high-risk group. This distribution reflects the need for greater experience and technical skill in more complex cases, and preoperative triage helps to select the most suitable cases for resident training.

Analysis of the results of the surgeon's subjective perception of the usefulness of the ICG included decisions that led to modifying their surgical strategy, such as: changing the dissection site of the gallbladder hilum, placing the clips, and the decision to perform a subtotal cholecystectomy.

In one in four (25%) high-risk cholecystectomies, surgeons modified the surgical procedure, compared with one in ten patients in the moderate-risk group and none in the low-risk group. Furthermore, ICG was considered useful in all groups, being more frequently classified as extremely useful in the high-risk group, but with no resulting statistical significance. These results support the clinical relevance of ICG as a valuable tool to improve intraoperative visualisation of the CBDJ and decision making in cases of greater technical difficulty.

Limitations of the present study include its observational and non-randomised design without a control group, the small sample size, and the dependence of the subjective assessment of the surgeon in part of the results obtained. Furthermore, an intraoperative classification of the difficulty of the cholecystectomy was not performed to corroborate Nassar's preoperative classification.

To conclude, the results of this study show that, in the case of difficult cholecystectomies, CBDJ visualisation is achieved in 63% of cases and leads to a modification in the surgical procedure in one out of four patients. For this reason, the authors consider that the availability of operating rooms equipped with fluorescence technology with ICG should be guaranteed for the performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomies that are a priori difficult.

Conflicts of interestMaría Luisa Galaviz-Sosa, Eric Herrero Fonollosa, María Isabel García-Domingo, Judith Camps Lasa, María Galofré Recasens, Melissa Arias Aviles, and Esteve Cugat Andorrà have no conflicts of interest.

This research did not receive any specific grant from public funding agencies, commercial or non-profit sectors.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Joaquín Rodríguez Santiago for his contribution in the review of the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Galaviz-Sosa ML, Fonollosa EH, García-Domingo MI, Lasa JC, Recasens MG, Aviles A, et al. Verde de indocianina en la colecistectomía laparoscópica: utilidad y correlación con un score preoperatorio de riesgo. Cir Esp. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2024.07.010