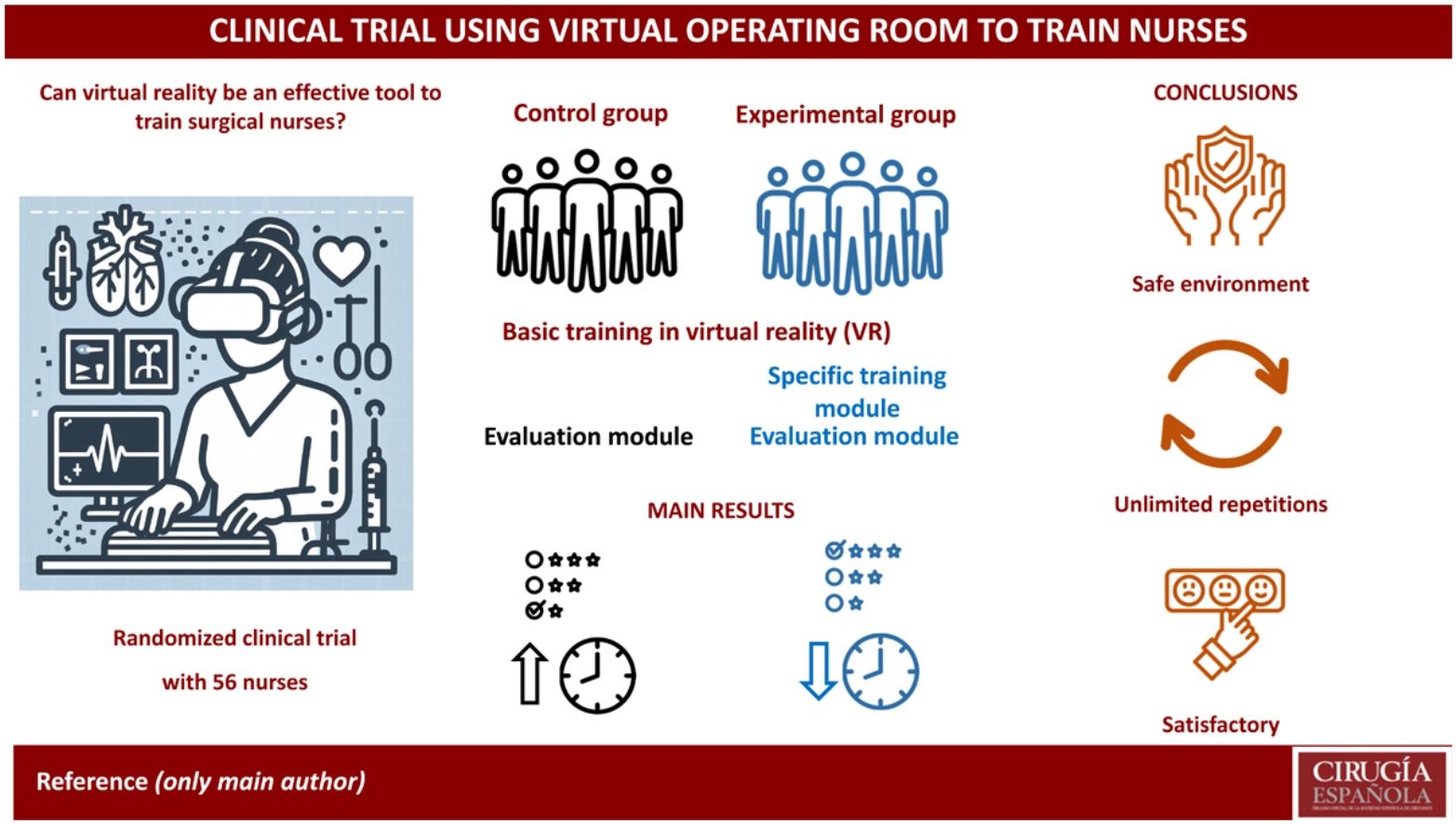

Virtual reality (VR) provides a firsthand active learning experience through varying degrees of immersion. The aim of this study is to evaluate the use of VR as a potential tool for training operating room nurses to perform thoracic surgery procedures.

MethodsThis is an open parallel-group randomized clinical trial. One group received basic formation followed by an assessment module. The experimental group received the same basic formation, followed by thoracic surgery training and an assessment module.

ResultsFifty-six nurses participated in the study (51 females), with a mean age of 41.6 years. Participants achieved a median evaluation mode score of 480 points (IQR = 32 points). The experimental group (520 points) achieved an overall higher score than the control group (440 points; P = .04). Regarding age, women in the second quartile of age among the participants (35–41 years) achieved significantly better results than the rest (P = .04). When we evaluated the results based on the moment of practice, exercises performed in the last 10 min obtained better results than those performed in the first 10 min (1064 points versus 554 points; P < .001). Regarding adverse effects blurred vision was the most frequent. The overall satisfaction rating with the experience was 8.5 out of 10.

ConclusionVirtual reality is a useful tool for training operating room nurses. Clinical trial with ISRCTN16864726 registered number.

La realidad virtual (RV) proporciona una experiencia de aprendizaje activo en primera persona a través de diferentes grados de inmersión. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar el uso de la RV como una posible herramienta para formar enfermeras de quirófano, realizando un procedimiento de cirugía torácica.

MétodosSe trata de un ensayo clínico aleatorio abierto de grupos paralelos. Un grupo recibirá una formación básica y un módulo de evaluación. El grupo experimental recibirá la misma formación básica, seguida de una formación en cirugía torácica y un módulo de evaluación.

ResultadosHan participado 56 enfermeras (51 mujeres), con una mediana de edad de 42 años. Los participantes obtuvieron una mediana de 480 puntos con un rango intercuartílico de 32 puntos. El grupo experimental obtuvo una puntuación global (520 puntos) mejor que el grupo control (440 puntos; p = 0.04). Las mujeres presentes en el segundo cuartil de edad de las participantes (35–41 años) obtuvieron resultados significativamente mejores que el resto (p = 0.04). Evaluando los resultados según el momento de la práctica, se ha observado que los ejercicios realizados obtenidos en la última parte de la evaluación han obtenido mejores resultados que los obtenidos en los primeros 10 minutos (1064 puntos frente a 554 puntos; p < 0.001). En relación a efectos indeseables la visión borrosa el más frecuentemente identificado. El grado de satisfacción global con la experiencia ha sido de 8.5 puntos (sobre 10 posibles).

ConclusionesLa realidad virtual es una herramienta útil en la formación de las enfermeras de quirófano. El ensayo clínico tiene el número de registro ISRCTN16864726.

Nursing is a practical discipline. In order for nurses to apply acquired theoretical knowledge within a clinical context, innovative teaching methods must be implemented to ensure the accurate application of knowledge and to narrow the theory-practice gap. However, traditional teaching techniques do not always seamlessly translate into clinical practice due to the disparity between classroom learning and real-life clinical settings.1

An approach that is being increasingly adopted involves the utilization of simulators that replicate clinical environments. The benefits include: a risk-free, interactive, realistic learning environment for nurses; various adaptable clinical scenarios; experiential learning outside the clinical domain; teamwork and communication are fostered through collaborative and supportive frameworks with multiple participants; the ability to repeat scenarios, allowing for increased exposure and error correction; and the improvement of technical and non-technical skills.2 Nonetheless, simulators also have inherent limitations, and the primary challenge is the resource-intensive development of high-fidelity simulators for diverse clinical scenarios. Interactivity and authenticity are also imperative.3

In recent years, one such simulation that has gained momentum due to the mainstream use of affordable technology is virtual reality (VR).2 VR involves computer-generated simulations of interactive 3-dimensional (3D) worlds that replicate real-life situations and medical procedures.4 Users experience spatial presence, interaction, and engagement. An essential element of VR is sensory feedback through multisensory stimulation, leading to a heightened sense of immersion, including comprehensive visual output, rapid movement detection, and haptic feedback. Immersion levels in VR can vary (low to high) based on simulation extent, such as the use of a head-mounted display (HMD) or a monitor screen. High immersion is linked to the suspension of disbelief through diverse stimuli to the brain, inducing a sense of environmental existence. A central tenet of VR is the virtual world — a computer-based simulated environment adhering to real-world principles. In essence, VR provides an immersive direct learning experience that empowers nurses to apply their knowledge meaningfully.5 This technology holds promise for continuous, unmonitored, cost-effective training.6

Aligned with the aforementioned interests, a Spanish company, Kauka, has developed a video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) simulator, which enables nurses to perform surgical procedures within a VR setting. Consequently, the aim of this study is to evaluate the use of VR software created to be a potential tool for training operating room nurses to perform thoracic surgery procedures.

MethodsStudy equipment: Head Mounted display (HMD) and simulatorWe employed the Meta Quest 2 HMD developed by Meta (Meta Quest 2 has a Qualcomm Snapdragon XR2 processor, with a RAM of 6GB and a screen resolution of 1832 × 1920 per eye with a refresh rate of 120 Hz), and we designed an application with 2 distinct scenarios for the HMD using the Unity Real-Time Development Platform (Unity Technologies):

Operating Table setup: places users in an operating room before the patient’s arrival (Fig. 1A). Another nurse is present in the room to demonstrate surgical instruments (SI) meant for use during surgery. This scenario aims to introduce participants to SI names and familiarize them with tool-handling concepts, while also assessing proper HMD positioning.

Operating Room Simulator: Participants are poised to begin surgery (Fig. 1B). The nurse stands on the right side of the patient (opposite the surgeon). For heightened immersion, users can observe surgery in progress by monitoring 2 room screens. This recording showcases the same surgery conducted at University Hospital Donostia (VATS-Right Upper Lobectomy). A continuous beeping sound simulates patient condition monitoring alarms. Correct tool handling triggers a cheerful sound, while incorrect execution prompts a program message reading "Incorrect Tool Selected." The program comprises 2 modules: Formation and Evaluation. Formation restricts interaction to the requested instrument, eliminating error possibilities. The tool is indicated by red arrows for precise location. In Evaluation, participants solely hear the instrument name called by the surgeon (as in real surgeries). Interaction with the software requires touch controller usage, symbolized as virtual hands. Left and right controllers correspond to respective hands. The only permitted action in the simulator is grasping. Pressing the back button on a touch controller closes the hand, flexing all fingers. Close proximity to any instrument enables users to pick up objects upon button press, retaining them until release.

Study design and participantsThe study was designed following recommendations of the paper “Reporting guidelines for health care simulation research: extensions to the CONSORT and STROBE statements”.7 This pilot study is an open, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial with 1:1 randomization and blind evaluation. Participants are operating room nurses lacking thoracic surgery experience who consented to participate and provided informed consent.

Inclusion criteriaOperating room nurses without prior thoracic surgery experience, irrespective of contract type or age.

Exclusion criteriaExclusion was solely determined by having participated in a thoracic surgery operating room within 24 months preceding the study.

Control groupControl group participants completed the basic training (Operating Table Setup) followed exclusively by the Operating Room Simulator in the Evaluation module.

Experimental groupExperimental group participants had the same basic training (Operating Table Setup) followed by the Operating Room Simulator in both Formation and Evaluation modes (Video 1; Supplementary Material).

Study variablesPrimary outcome variables: Number of Completed Tasks (range 0–46), Individual Task Scores (20 for correct performance, 0 for incorrect), Time Spent in the Simulator (in minutes), Overall Score (sum of task scores, max: 1000).

Secondary outcome variables. Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) and satisfaction test.

Demographic variables: age, gender, dominant hand (right-handed, left-handed, ambidextrous), videogame usage.

RandomizationA computer-based randomization sequence was developed. This sequence was kept in the clinical epidemiology department, so that the supervisor recruiting the participants did not know in advance to which group the participant would be assigned (hidden randomization sequence). Once the participants signed the consent form, an opaque envelope was opened with the assignment to either the control or experimental group.

MaskingThe simulator automatically records primary outcomes and assigns a code number to each participant. The researcher remains unaware of group assignments until the final analysis because the association between the code and the group was kept in a separate file.

Sample sizeTo help calculate the sample size, 2 nurses with experience in thoracic surgery instrumentation performed the assessment module, both correctly and making voluntary errors. When the correct and incorrect performances were compared, differences of up to 30 points were observed. Therefore, the study was designed to detect differences greater than 30 points. Accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.20 (equivalent to a statistical power of 80%) in a bilateral comparison, 56 patients in total were needed to detect a statistically significant difference equal to or greater than 30 points in the overall score.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of variables using median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables was performed. The distribution of the variable of interest among the 2 groups (control and experimental) was analyzed using the chi-square test and Mann–Whitney for categorical and quantitative variables, respectively. R software (version 4.2.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Viena, Austria) was utilized.

Ethical considerationsWhile participants were not queried about medical records or conditions, the study gained approval from the Gipuzkoa Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC) due to its experimental nature (see Annex 1). Data collection followed good clinical practice guidelines and Data Protection Law principles.

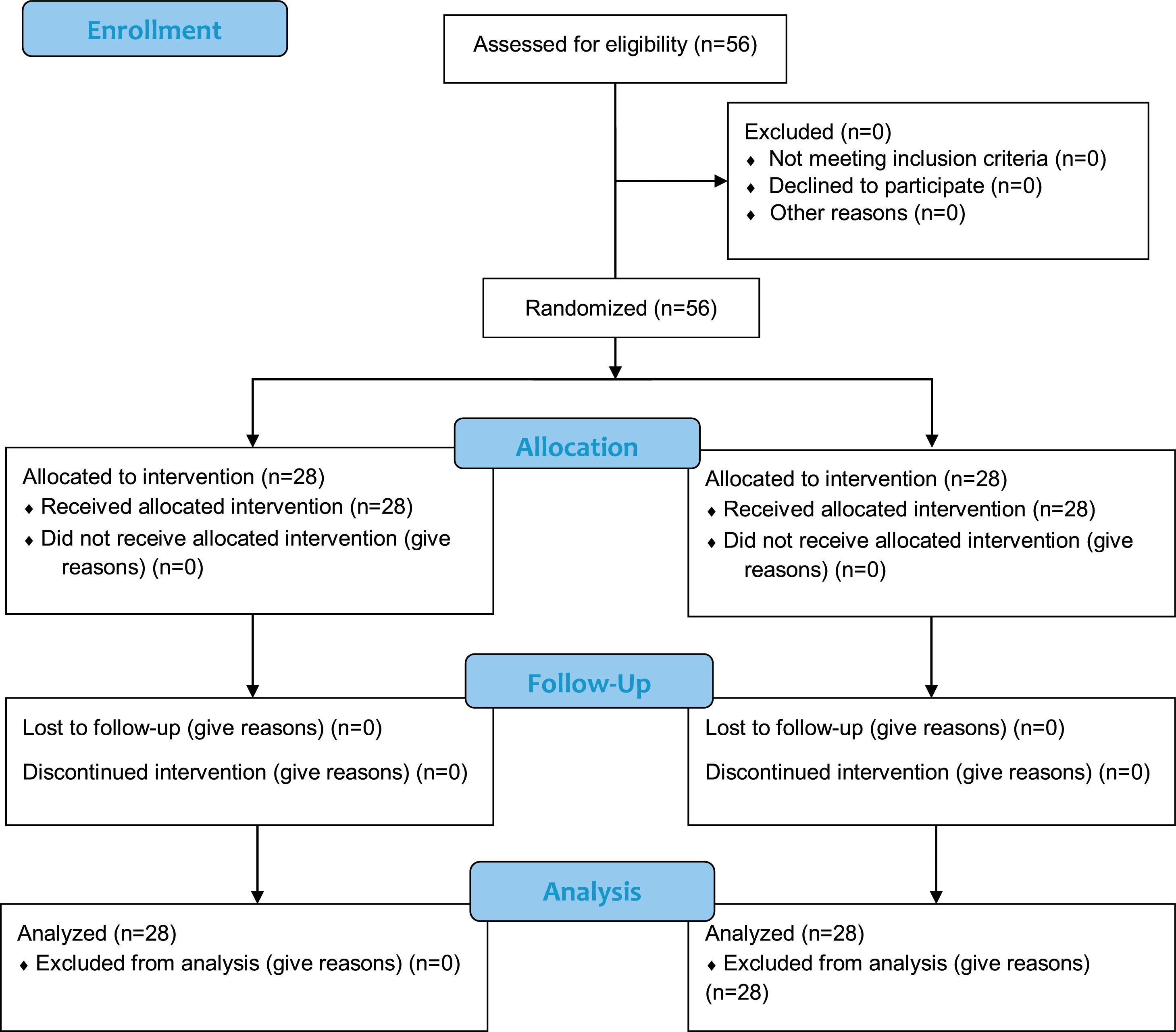

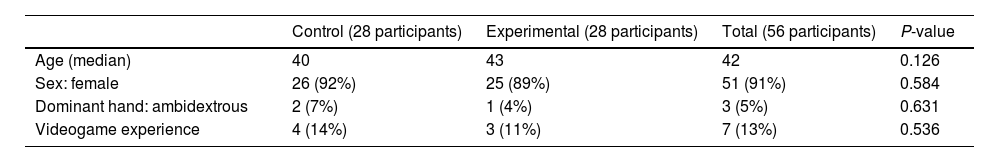

ResultsParticipants descriptionA total of 56 nurses were included for randomization, and all completed the trial (Fig. 2, Participant flow-chart). The median age was 42 years (IQR = 12), with 51 females and 5 males. There were no left-handed participants; 53 nurses were right-handed, and 3 identified as ambidextrous. Seven of the participants reported prior experience with video games. Both control and experimental groups included 28 participants (Table 1).

Distribution of demographic variables.

| Control (28 participants) | Experimental (28 participants) | Total (56 participants) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median) | 40 | 43 | 42 | 0.126 |

| Sex: female | 26 (92%) | 25 (89%) | 51 (91%) | 0.584 |

| Dominant hand: ambidextrous | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (5%) | 0.631 |

| Videogame experience | 4 (14%) | 3 (11%) | 7 (13%) | 0.536 |

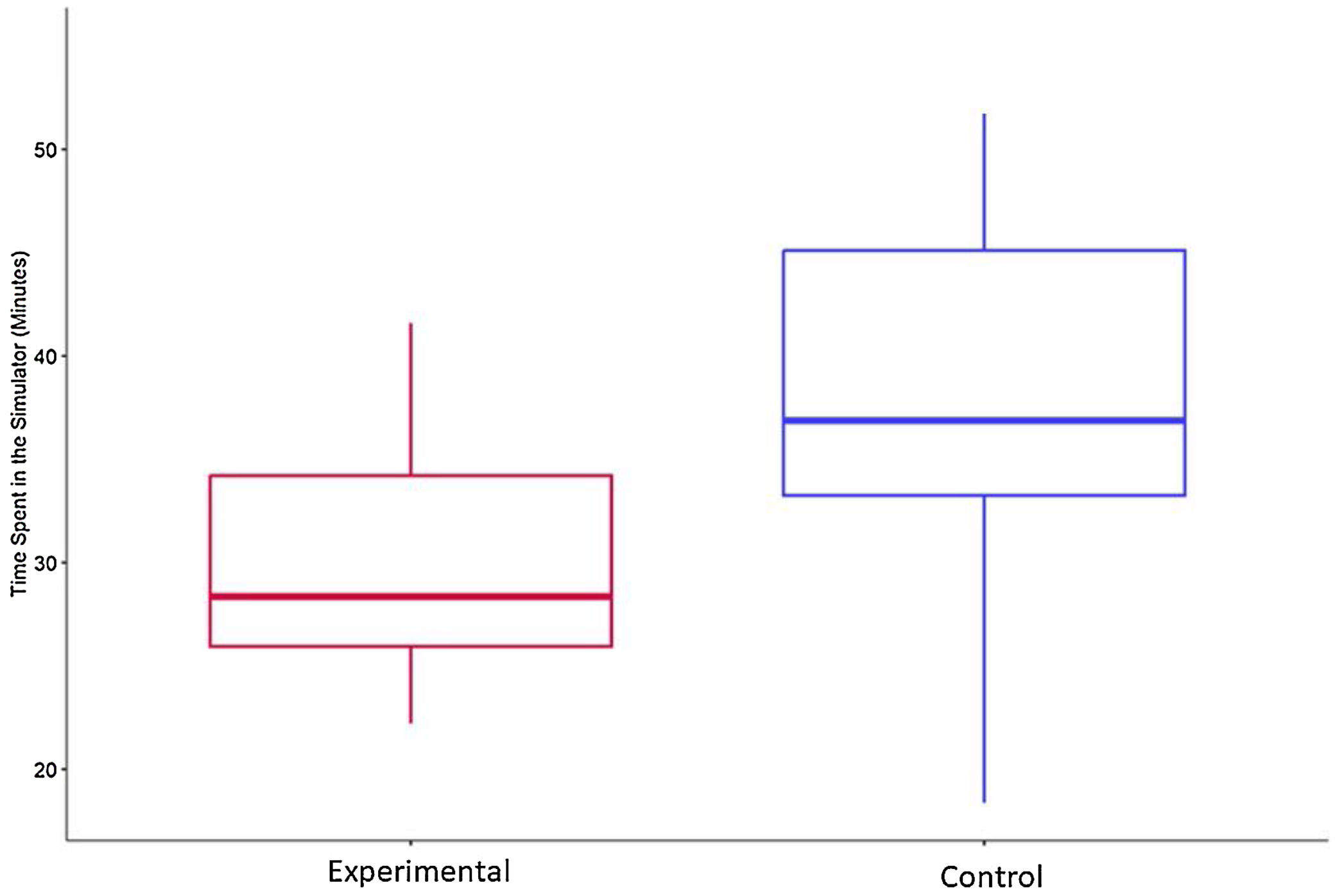

Participants spent a median of 33 min in the simulator: 29 minutes (IQR = 9 min) for those in the experimental group and 35 min (IQR = 12 min) in the control group (P < .01) (Fig. 3). The median number of completed tasks was 21 (IQR = 6), with a median of 19 tasks completed in the control group and 22 tasks in the experimental group (P .12).

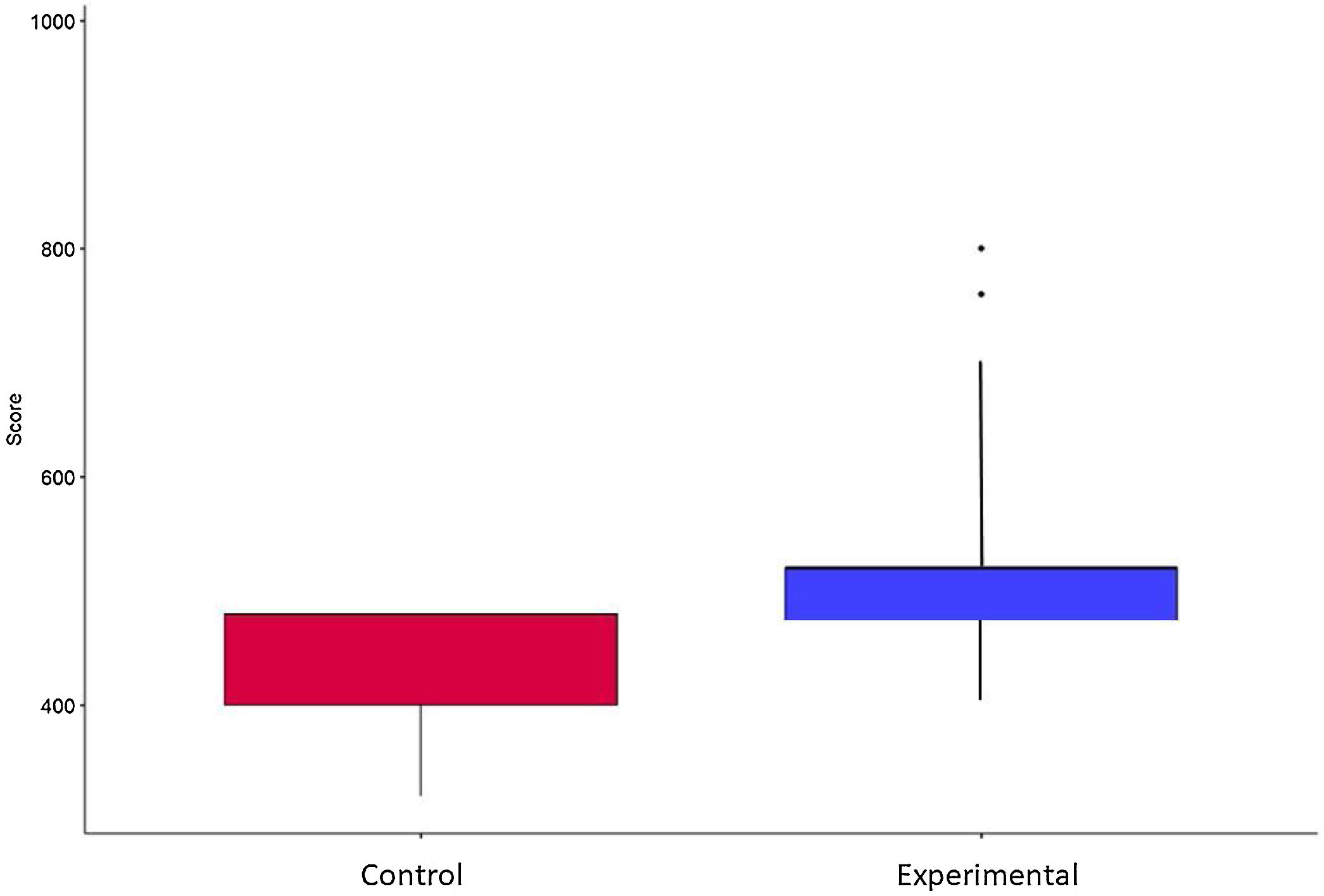

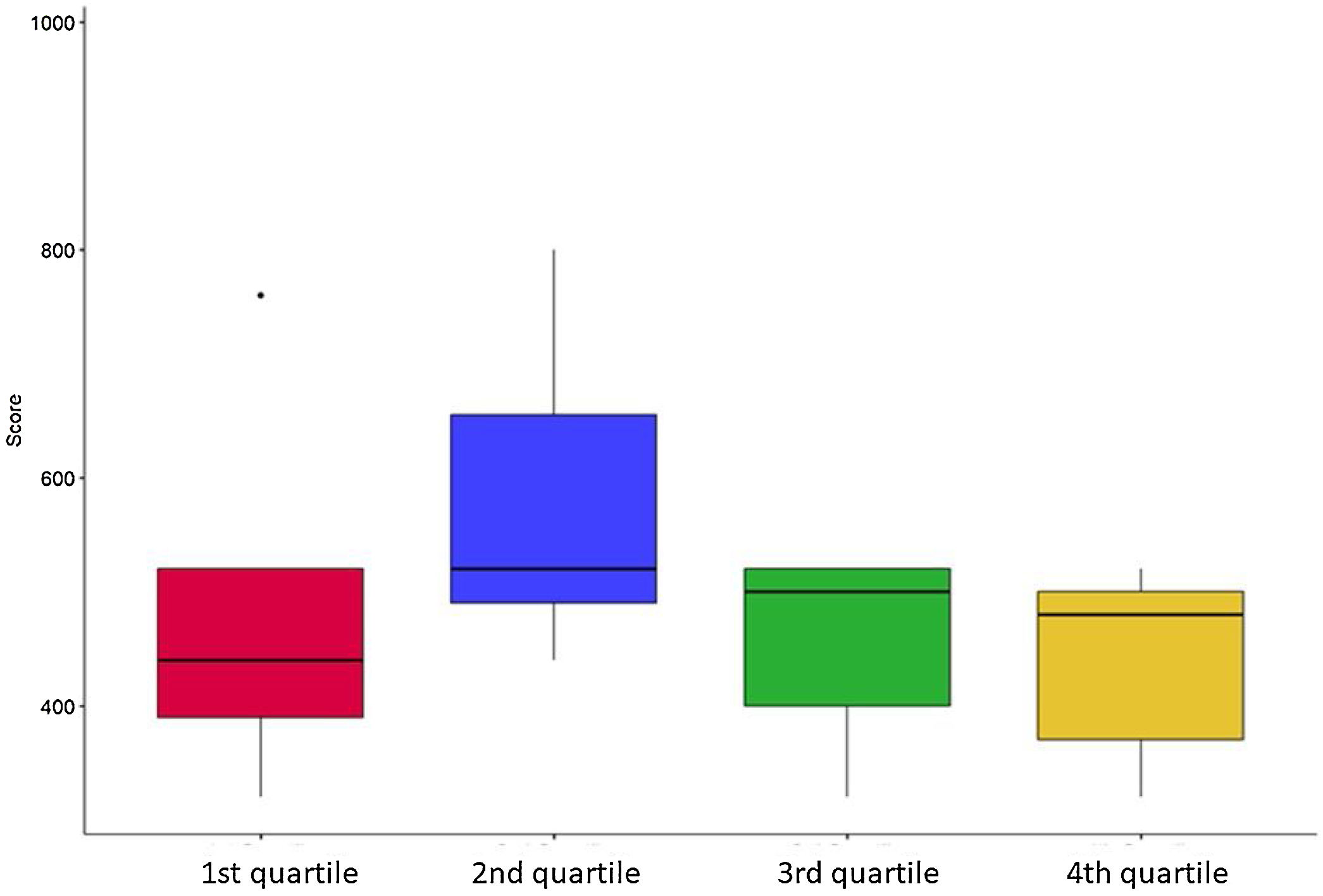

Participants achieved a median average evaluation mode score of 480 points (IQR = 32 points). The majority of the scores clustered around the 500-point mark, with only 4 participants surpassing 700 points. The experimental group (median 520 points; IQR = 29 points) achieved an overall higher score than the control group (median 440 points; IQR = 32 points; P = .04) (Fig. 4). In terms of age, individuals in the second quartile (35–41 years) exhibited notably superior results compared to the other age groups (P = .04) (Fig. 5). Gender and dominant hand were not found to have a significant impact on performance (P-values = 0.874 and 0.5495, respectively). It is important to note that both variables were underrepresented in the opposite group (5 males and 3 ambidextrous participants). Regarding video game experience, the median score for players was 510, while non-players achieved a median score of 470 (P-value = .5952).

When examining results based on the moment when they were practiced, tasks completed within the last 10 min yielded higher scores compared to those accomplished in the first 10 min (1064 points vs 554 points; P < .001).

Secondary effects and satisfaction assessmentA total of 26 participants reported no side effects. None of the participants experienced severe or moderate symptoms, and 30 participants reported one or more symptoms, all classified as mild (Supplementary Table S1). The most prevalent undesired effects were, in descending order: blurred vision (25 participants), difficulty focusing vision (14 participants), and sweating (10 participants). A comparison of the scores of participants with symptoms (475 points) versus those without symptoms (480 points) revealed no statistically significant differences (P = .85).

Out of the 52 nurses who responded to the satisfaction survey (supplementary Table 2), the overall satisfaction rating for the experience was 8.72 (Range 6–10). The likelihood of recommending this experience to a colleague received a score of 8.96 (Range 6–10). The statement that garnered the highest rating was: "The chosen teaching methodology was appropriate," receiving a score of 9.16 (Range 7–10).

DiscussionIn the field of thoracic surgery, as in many specialized medical disciplines, the importance of nurse training cannot be overstated. Operating room nurses play a critical role in ensuring the smooth flow of surgical procedures, patient safety, and the overall success of the surgical team.8 The ability of nurses to effectively perform their duties relies heavily on comprehensive training and versatility.9

In today’s healthcare environment, where medical procedures are becoming increasingly complex, it is crucial for nurses to receive extensive, specialized training.10 This not only enhances their knowledge but also boosts their confidence and competence in the operating room. As demonstrated in the study, the nurses who received thoracic surgery training in a VR environment outperformed their counterparts who had received only basic training. This highlights the significance of specialized training, particularly in fields as intricate as thoracic surgery.

Furthermore, the versatility of operating room nurses is of paramount importance. The ability to adapt to different surgical procedures, instruments, and scenarios is vital.11 VR technology provides a platform for nurses to explore and adapt to various clinical situations in a controlled, risk-free environment. This adaptability is particularly critical in the dynamic and ever-evolving field of healthcare, where new techniques and technologies constantly emerge.12 Therefore, we continue to pursue the utility of new technologies for training, demonstrating their usefulness and advantages over more traditional systems.10,13–15

The integration of virtual reality (VR) into nurse training programs represents a paradigm shift in medical education.16 VR offers an immersive and interactive learning experience that can significantly enhance the training of healthcare professionals, including operating room nurses.17,18 A recent article compared training for trauma injuries using more traditional systems versus VR and found VR to be superior in a select group of participants.15 Meanwhile, the results of the meta-analysis published by Alaker et al. showed that virtual reality simulation is significantly more effective than video trainers and at least as good as box trainers for abdominal surgery training.19

In the study conducted, the VR-based training program demonstrated its utility by allowing nurses to practice thoracic surgery procedures in a virtual operating room. This technology offers several advantages, including the ability to replicate real-life surgical scenarios with a high degree of accuracy.20,21 The immersive nature of VR allows nurses to gain hands-on experience without the risks associated with actual surgical procedures, thus contributing to improved patient safety.22 Along the same line, we can find several articles that demonstrate that the use of VR can reduce the risks of surgeries thanks to different advantages: it improves the anatomical study of patients by foreseeing unexpected variations,13 it allows for selective intubation in thoracic surgery before surgery,14 and it improves operative efficiency and communication across multiple surgical specialties.23

It is worth noting that the results of the satisfaction survey yielded highly positive outcomes. Participants rated the chosen methodology (VR), as appropriate and effective for their training. Overall satisfaction with the virtual reality training experience was remarkably high, with an average rating of 8.72 out of 10. These results would be in line with those published by Allan et al., who analyzed VR in traumatology and observed high satisfaction among participants (4 points out of 5) and would recommend VR to their peers in 88% of cases.24 This underscores the notion that the utilization of virtual reality as a training tool not only enhances performance, as demonstrated in the preceding results, but also generates a highly satisfactory learning experience. These findings support the feasibility and positive acceptance of virtual reality as a training tool in the field of surgical nursing, suggesting its potential to transform education and clinical practice in the future.

LimitationsOne of the fundamental limitations of this study is the lack of objectivity regarding how the learning acquired in the virtual reality environment would translate to the real world. Although the results show improvements in nurses’ performance in a virtual environment, the ability to apply these skills and knowledge in real surgical settings has not been assessed. It is essential to consider that the transition from a controlled virtual environment to a real operating room may involve additional challenges, such as stress, communication with the surgical team, and adaptation to actual patient conditions. Therefore, follow-up studies are needed to evaluate the effective transfer of skills acquired in the virtual environment to clinical practice. The review published in 2024 also referred to the same limitation, and, after analyzing several studies evaluating simulators to improve the anesthetic part of thoracic surgery (one-lung ventilation and lung exclusion), the authors concluded that simulation is a useful tool, but more clinical trials were needed and, above all, a way to measure its impact on routine clinical practice.14

Another significant limitation is that the study focused on only one type of surgery, in this case, thoracic surgery. Techniques and procedures in surgery can vary significantly among specialties and subspecialties. Therefore, the results obtained may not be generalizable to other types of surgery, or even different approaches within thoracic surgery. It would be valuable to conduct further research to assess the effectiveness of virtual reality training in a variety of surgical specialties and with surgeons using different approaches and strategies. This would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the utility of VR in surgical training.

Additionally, the sample of participants was limited to operating room nurses with no prior experience in thoracic surgery, which may not fully reflect the diversity of experiences and skills in the field of surgical nursing. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and applying the findings in broader clinical contexts.

In summary, while this study shows promising results in the use of virtual reality for training nurses in thoracic surgery, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations, including the lack of evidence of transfer to the real world and the limited application to a specific type of surgery. These limitations underscore the need for further research and the consideration of contextual factors when applying these findings in clinical practice.

ConclusionIn conclusion, the use of VR is a useful tool in nurse training, especially for specialized roles like operating room nurses in thoracic surgery. It not only enhances their ability to perform complex procedures but also promotes adaptability and versatility.

Sources of fundingBotton-up program, Basque Health Service 22BU213.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.