Post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) is defined as the inability of the post-resection liver remnant to maintain normal total bilirubin and INR levels after the fifth day post-op.1 In order to minimize the appearance of this complication, it is essential to leave an adequate volume of remaining liver, which will depend on whether the hepatic parenchyma presents some type of lesion and its severity. In the case of livers with colorectal metastasis treated with preoperative chemotherapy, this volume has not been well defined, which, together with oncologic-surgical treatments that are becoming more and more aggressive, has led to PHLF currently being the main cause of death after liver resection due to colorectal cancer metastasis.2

There is little information about the best treatment for this complication once it has been established as it is considered a very serious situation with few therapeutic alternatives. The molecular absorbent recirculating system (MARS) is an extracorporeal liver dialysis system that uses a liquid solution rich in albumin to partially substitute the filtering function of the liver. It has been proposed by some authors as a treatment option, although it has not been shown to increase the survival of these patients in the few articles that have been published.2–5

We present the case of a 48-year-old female patient with 7 bilobar liver metastases. The lesions were colorectal in origin and resected with right hepatectomy, with limited resection of 2 tumors in the left liver. Given the small size of the masses, we decided to use a direct surgical approach to avoid the disappearance of the lesions from the left side with chemotherapy. The volume of the left liver lobe calculated by CT was 32%; this was considered adequate, so preoperative portal embolization was not done. Surgery was completed without clamping the pedicle and blood loss amounted to 300cm3.

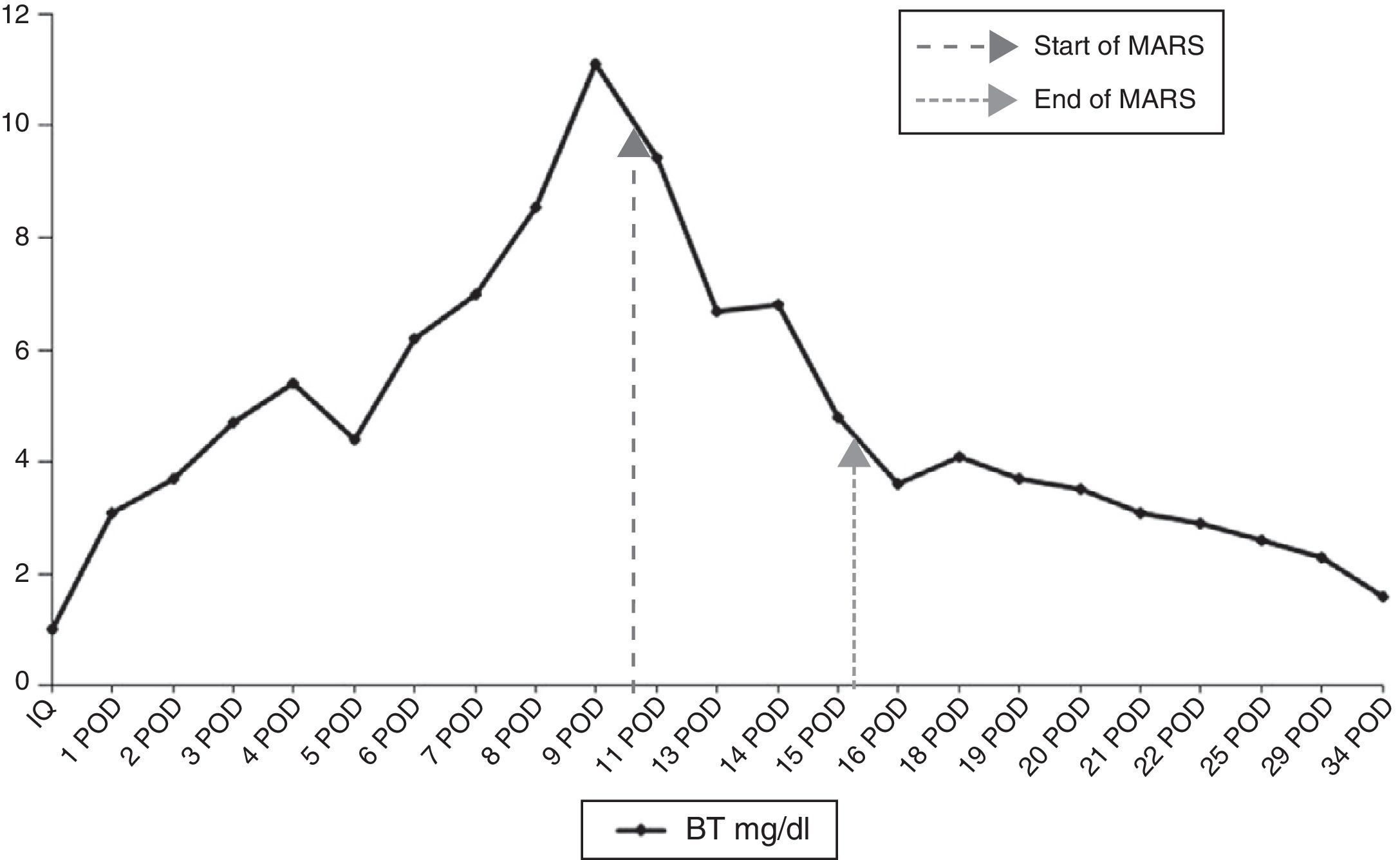

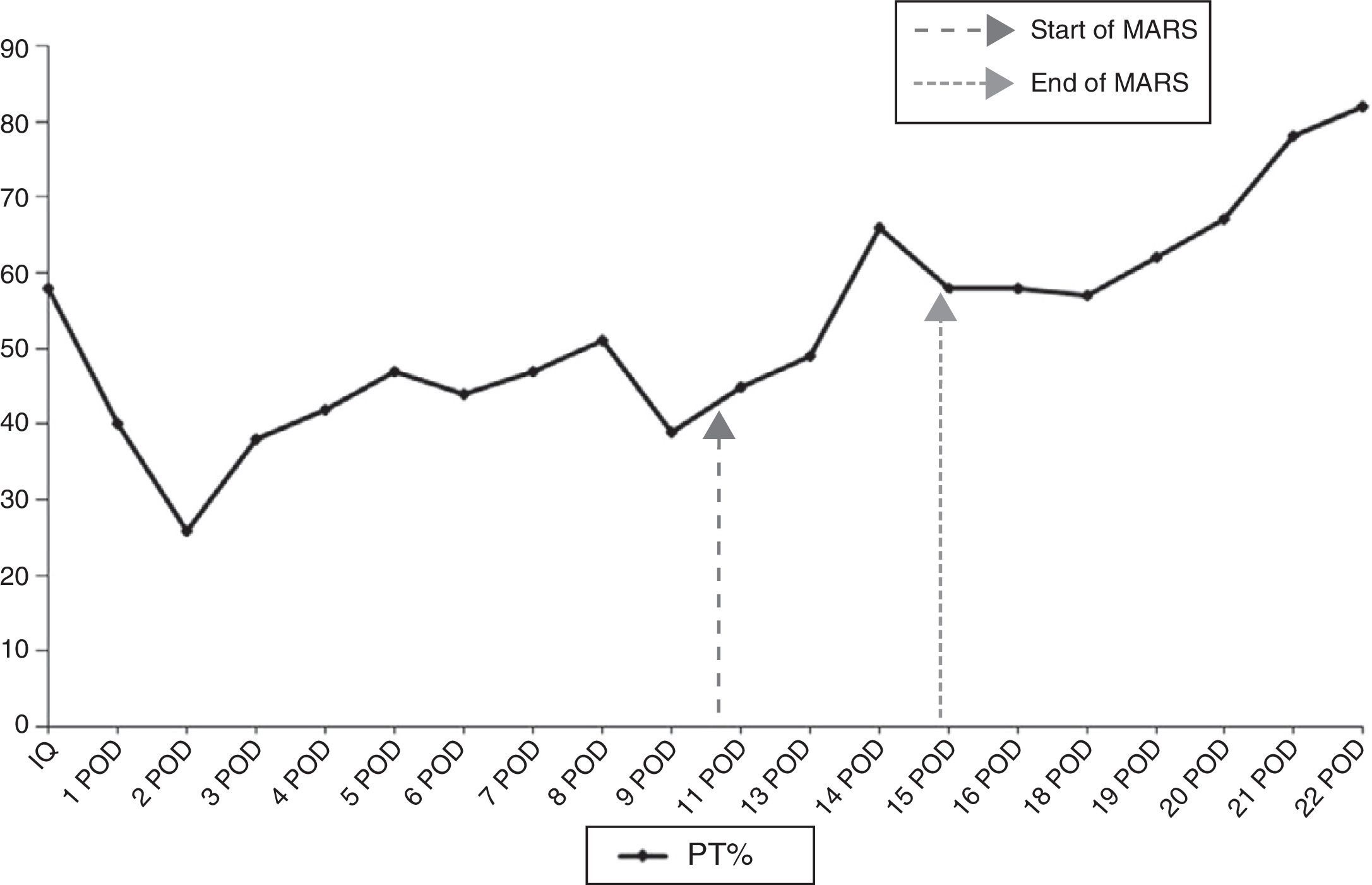

During the immediate postoperative period, the patient presented a good general state with no signs of encephalopathy, bleeding or infection. We did observe, however, a progressive decline in the hepatic profile with total bilirubin levels that progressively reached 11mg/dl on the 9th day post-op, together with prothrombin time (PT) of 47%; the indocyanine green plasma disappearance rate (ICG-PDR) at that time was 10%/min. After a CT scan and exploratory laparotomy that ruled out a bile leak, bleeding or intraabdominal abscess, the only condition that justified PHLF was a culture of the drained liquid positive for pseudomonas, which was treated according to the antibiogram. Given the progressive liver function deterioration, it was decided to administer 4 MARS sessions after the 10th day post-op, which progressively reduced bilirubin levels and increased PT (Figs. 1 and 2). The patient was discharged 30 days after the procedure with bilirubin 2.3mg/dl and PT 82%.

This complication was unexpected since the patient had not received preoperative chemotherapy, the procedure was done without clamping and with very limited bleeding, and the volume of the liver remnant was larger than 30%. Nonetheless, this calculation was made by measuring the total volume of the liver on CT and not by using the standardized formula based on surface area, which could have underestimated risk for PHLF.6 Furthermore, infection of the surgical site may have perpetuated the symptoms, although we do not believe that this was the cause. It probably occurred after the second procedure, because until that time the leukocyte count and the appearance of the drained fluid were completely normal. It is difficult to know if the patient would have spontaneously recovered liver function with treatment of the surgical site infection alone. But, as bilirubin levels above 7mg/dl in cases of PHLF are a strong predictor for mortality,7 we decided to apply the MARS treatment straight away.

Experience with the use of MARS for the treatment of PHLF is very limited, with only 15 published cases and a mortality of 80%.2–5 Nonetheless, in most of these cases, treatment was initiated later on or in patients with multi-organ failure. According to Inderbitzin et al.,5 the main prognostic factor for response to treatment is minimal liver functionality, defined by a ICG-PDR >5%/min. In our case, the treatment was applied early on, there were no serious surgical complications that perpetuated the PHLF and the liver function at the time of maximum hyperbilirubinemia was relatively good (ICG-PDR 10%/min), which could explain the satisfactory evolution of our patient.

Conflict of InterestsNo funding was received for this article, and the authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Martin Malagon A, Pezzetta L, Arteaga Gonzalez I, Diaz Luis H, Carrillo Pallares Á. Tratamiento del fallo hepático después de hepatectomía mediante sistema de diálisis hepática MARS. Cir Esp. 2014;92:688–690.

This paper was presented as a poster communication at the 29th National Meeting of Surgeons held in Burgos, Spain on October 23–25, 2013.