Innovation in internet connectivity and the Covid 19 pandemic have caused a dramatic change in the management of patients in the medical field, boosting the use of telemedicine. A comparison of clinical outcomes and satisfaction between conventional face-to-face and telemedicine follow-up in general surgery, an economic evaluation is mandatory.

The aim of the present study was to compare the differences in economic costs between these two outpatient approaches in a designed randomized controlled trial (RCT).

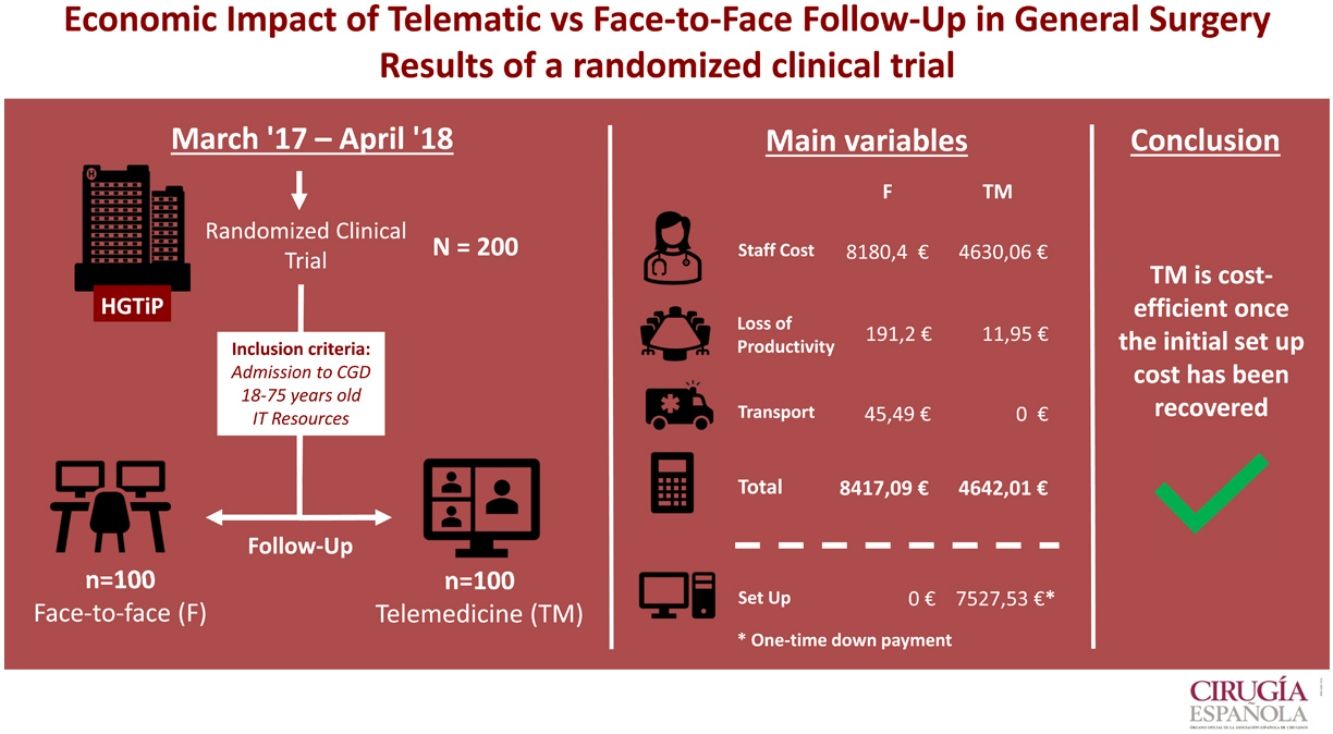

MethodsA RCT was conducted enrolling 200 patients to compare conventional in-person vs. digital health follow-up using telemedicine in the outpatient clinics in patients of General Surgery Department after their planned discharge. After a demonstration that no differences were found in clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction, we analyzed the medical costs, including staff wages, initial investment, patent’s transportation and impact on social costs.

ResultsAfter an initial investment of 7527.53€, the costs for the Medical institution of in-person conventional follow-up were higher (8180.4€) than those using telemedicine (4630.06€). In relation to social costs, loss of productivity was also increased in the conventional follow-up.

ConclusionThe use of digital Health telemedicine is a cost-effective approach compared to conventional face-to-face follow-up in patients of General Surgery after hospital discharge.

La innovación en la conectividad a internet y la pandemia de Covid 19 han provocado un cambio dramático en la gestión de pacientes en el ámbito médico, impulsando el uso de la telemedicina. Una comparación de resultados clínicos y satisfacción entre el seguimiento convencional presencial y por telemedicina en cirugía general, es obligatoria una evaluación económica. El objetivo del presente estudio fue comparar las diferencias en los costos económicos entre estos dos enfoques ambulatorios en un ensayo controlado aleatorio (ECA) diseñado.

MétodosSe realizó un ECA que inscribió a 200 pacientes para comparar el seguimiento de salud convencional en persona versus el seguimiento de salud digital mediante telemedicina en las clínicas ambulatorias en pacientes del Departamento de Cirugía General después de su alta planificada. Después de demostrar que no se encontraron diferencias en los resultados clínicos y la satisfacción del paciente, analizamos los costos médicos, incluidos los salarios del personal, la inversión inicial, el transporte de patentes y el impacto en los costos sociales.

ResultadosDespués de una inversión inicial de 7.527,53 €, los costes para la Institución Médica de seguimiento convencional presencial fueron superiores (8.180,4 €) que los de telemedicina (4.630,06 €). En relación a los costos sociales, la pérdida de productividad también se incrementó en el seguimiento convencional.

ConclusiónEl uso de la telemedicina digital en Salud es un enfoque costo-efectivo en comparación con el seguimiento presencial convencional en pacientes de Cirugía General después del alta hospitalaria.

Digital Health using Telemedicine (TM) has been introduced in the medical field since 20 years ago.1,2 One of its main purposes was to increase access to Healthcare in rural areas which were far away from hospitals, such in countries like Australia, China or India.3,4 In a century where medicine has evolved sophisticating most of its diagnostic tools and procedures this has traduced a great increase in its related costs.5–7 A need to reduce them has turned to be necessary and in this context, another purpose of TM has been considered to reduce medical costs.

In the literature, there are several studies regarding TM uses in medical specialties, like dermatology, pediatrics, rheumatology, radiology, cardiology and endocrinology but less in the surgical field.8–13 In those cases, the studies are mostly developed in orthopedic surgery and little of them were randomized clinical trials (RCT).14

Recently, TM has taken more relevance due to an improvement in digital devices (smart phones, high-definition cameras) as well as the availability of high-speed internet connectivity. Both of them have become part of our everyday life, making patients and doctor’s connection easier.9 In fact, in 2018 the penetration of smartphones in Europe reached 67,3%15 and in march 2021, 5G commercial services were deployed in 24 of 27 European Countries.16 Moreover, due to Covid-19 pandemic, the use of TM services has increased dramatically. In this context, due to mobility and capacity restrictions, conventional healthcare protocols have been outdated.17–19 Hospitals and physicians have done a big effort to move from the conventional medicine to the new circumstances. TM has busted into medical life making the communication between patients and physicians easier. It has settled up a new medical concept/way of life.

Nevertheless, there are several costs associated with the development and implementation of TM systems like equipment, staff and Communications network. But on the other hand, TM is a potentially cost-saving approach and even may be more efficient than current clinical practice. Thus, an economic assessment is needed. Although there are several systematic reviews evaluating its costs, results are dissimilar,7,20–23 so there is a lack of scientific evidence of the economic impact of telemedicine services.

In this context, in 2017−18, we conducted a RCT in the outpatient office of a General Surgery Department to compare the follow up of postoperative patients: control group had a face-to-face follow up (conventional) and experimental group using a telematic visit.14 The aim of the present study was to provide scientific evidence about the cost-effectiveness of TM on the basis of clinically proven RCT.

MethodsA prospective RCT following CONSORT guidelines was carried out with two parallel groups, one with conventional face-to-face follow-up after treatment in the outpatient clinic and the other with telemedicine follow-up through a video call.

Hospital settingsHospital Germans Trias i Pujol is a tertiary care university hospital located in the outskirts of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain). The hospital is a referral center, providing healthcare to more than 1.200.000 inhabitants.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaInclusion criteria consisted of being treated in the General Surgery department, basic computer knowledge (ability to use e-mail or a social network), having the necessary equipment (computer with webcam) and age between 18 and 75 years or having a partner who met these criteria.

Exclusion criteria were any disability making telemedicine follow-up impossible, such as blindness, deafness or mental disability, proctologic treatment, due to the difficulty of describing and showing complications in the surgical area, and clinical complications before discharge more severe than Clavien Dindo II. Patients were also excluded from the study if they withdrew consent. Patients who met these criteria were offered by the surgeon in charge the chance to enroll in the study the moment they were discharged from the hospital. If they agreed, they provided informed consent and were randomly allocated to each group of the study.

RandomizationAllocation was performed using a computerized block randomization list with an allocation ratio 1:1. Nevertheless, because of workload in the outpatient clinic, the enrollment of patients in the study was limited to 10 patients per week.

Study outcomesThe primary outcome was to assess the cost-effectiveness of TM vs the conventional in-person follow up following the CHEERS Guidelines27 based in a social perspective. Different items were measured.

- a)

Staff costs:

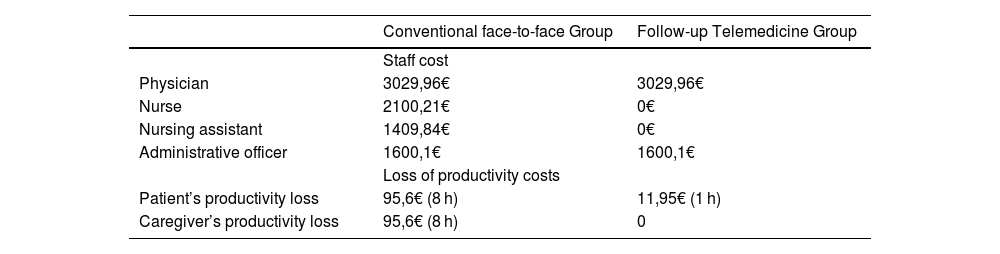

We took into consideration the required staff’s wages such as physicians, nurses, nursing assistant and administrative officer.30Table 2 shows the monthly mean gross salaries in Spain in each group.

- b)

Loss of productivity:

We looked through the costs attributed to the loss of productivity due to work absenteeism (both the patient and the caregiver). We considered a loss of 8 h of productivity (a day off) for both the patient and the caregiver in the conventional follow-up group. We assumed a loss of 1 h per patient in the group of TM although in the 97% of them, the length of the visit was less than 20 min.14 The average wage in Spain in 2020 was 11,95€/h24 (Table 2).

- c)

Transport costs:

As the hospital is located in the outskirts of the city and the public transportation is scarce, all the patients needed a private transport to reach the center, either their own car or an ambulance. We used the “Via Michelin” application to calculate this item when using private transport, as it takes into consideration kilometers, tolls and petrol. The hospital has an agreement with the company Ambulances Group La Pau with a cost per patient of 40,29€ per journey.

- d)

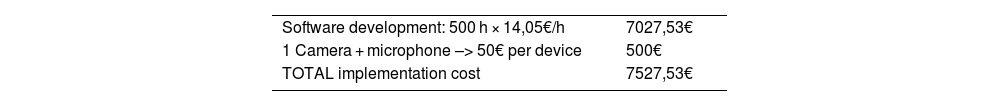

Installation and software development:

The initial investment for the software and the hardware (microphone and camera) was also taken into consideration. The software cost was calculated based on the time needed for its implementation (about 500 h) and the price per hour of a computer technician.25 This investment included 10 devices (camera + microphone) (Table 3).

Sample sizeWe used the sample size of the RCT that was calculated to assess the feasibility, clinical outcomes and satisfaction of a TM service. Accepting an alpha level of 0.05 and a beta level of 0.10 with bilateral contrast, we needed 84 patients per group to detect differences between the proportion of patients that failed the follow-up, which we calculated as 10% in the conventional group and 30% in the telemedicine group. With these results, the final study sample comprised 200 patients, 100 in each group.

Statistical analysisTo compare the proportion of the outcomes between the groups, categorical variables were analyzed using a Chi-Square test. To compare medians between groups, ordinal variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test Statistical significance was set bilaterally at P < .05. The statistical study was performed using the SPSS™ program (Version 24) by an independent researcher and following a per protocol analysis.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was reviewed and accepted by the Germans Trias i Pujol Hospital Review Board, the project was registered in Clinical Trials (NCT3304509), and written consent was obtained from all the patients enrolled. No funding was received for the study.

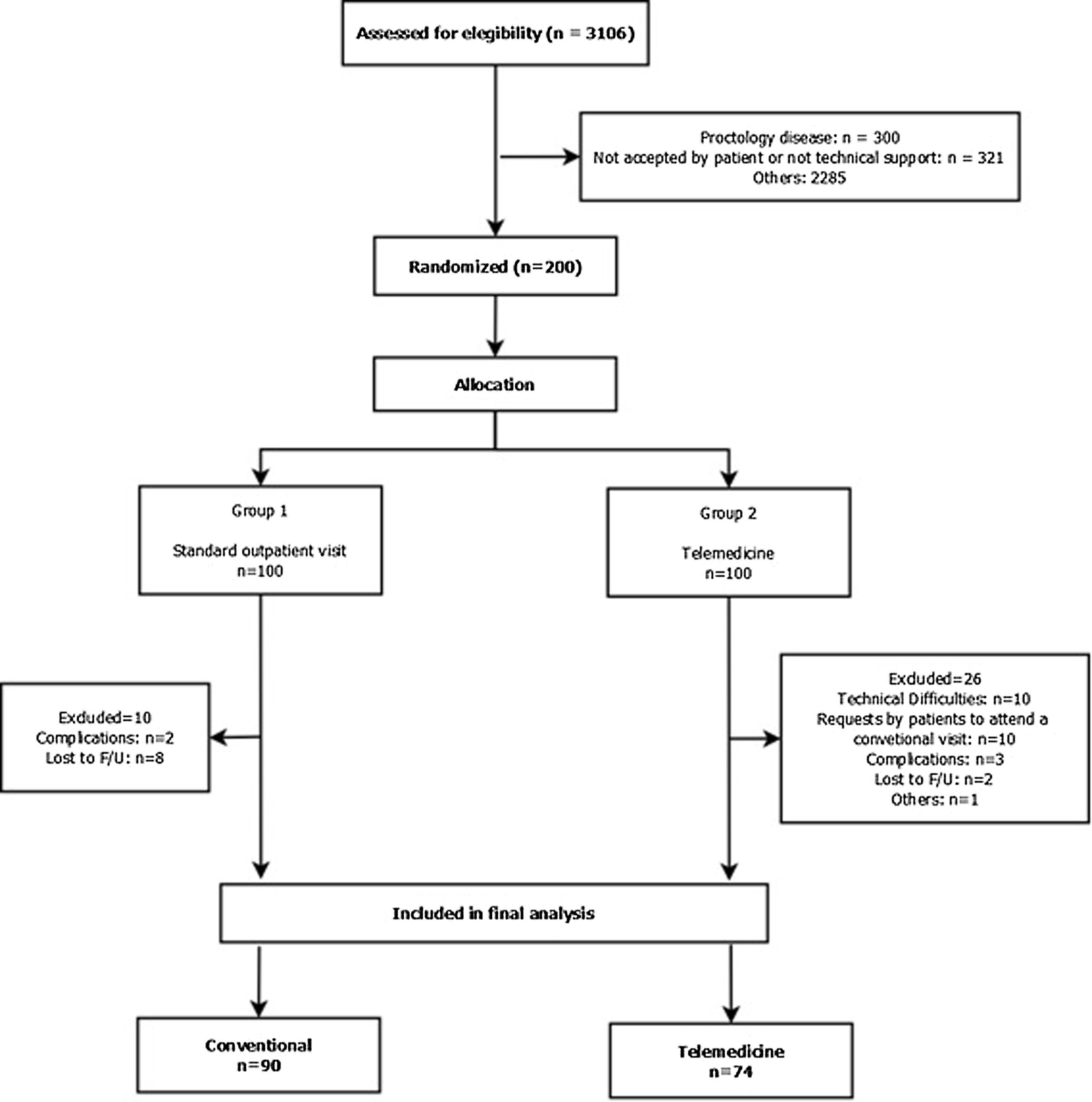

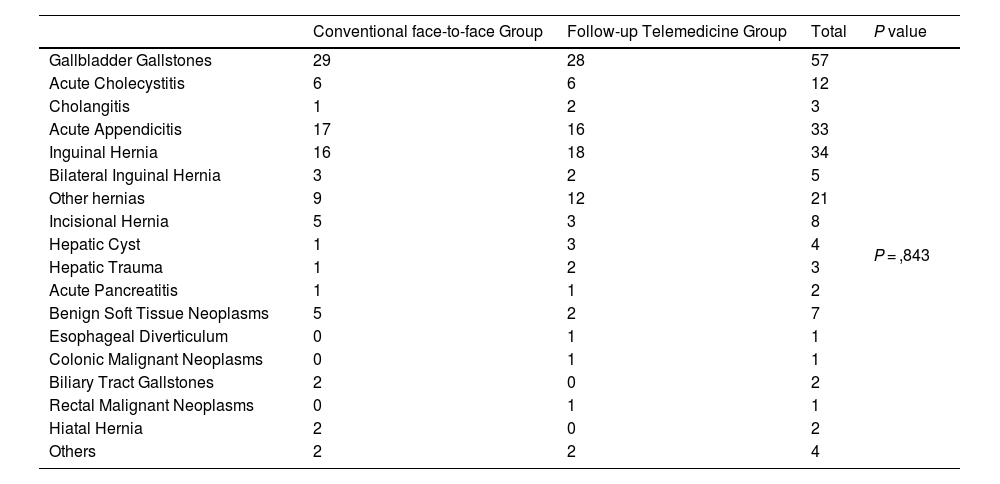

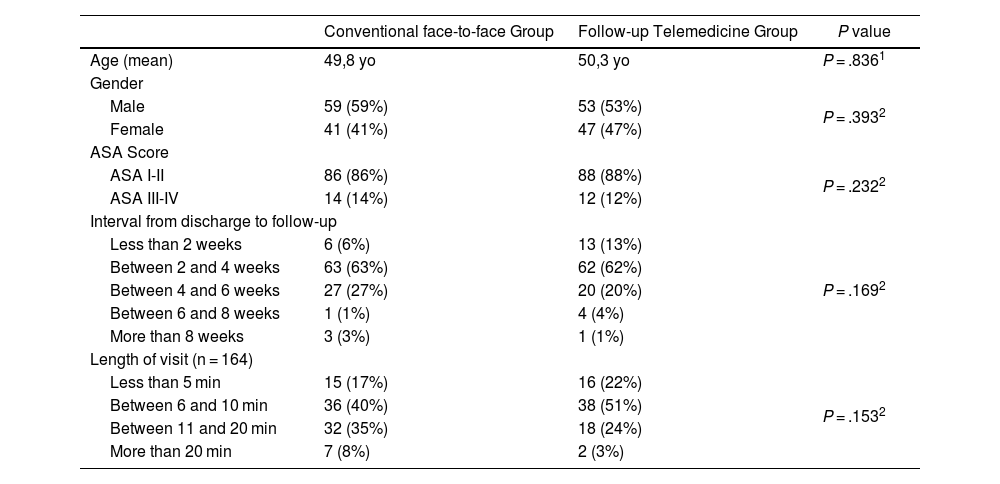

ResultsPatient enrollment and group characteristicsBetween March 2017 and April 2018, 200 patients were randomly allocated to one of the groups, with 100 patients in each arm of the study (Fig. 1) and Table 1. There were no statistical differences between group’s characteristics (Table 4).21

Diagnostics in each group of study.

| Conventional face-to-face Group | Follow-up Telemedicine Group | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallbladder Gallstones | 29 | 28 | 57 | P = ,843 |

| Acute Cholecystitis | 6 | 6 | 12 | |

| Cholangitis | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Acute Appendicitis | 17 | 16 | 33 | |

| Inguinal Hernia | 16 | 18 | 34 | |

| Bilateral Inguinal Hernia | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Other hernias | 9 | 12 | 21 | |

| Incisional Hernia | 5 | 3 | 8 | |

| Hepatic Cyst | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Hepatic Trauma | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Acute Pancreatitis | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Benign Soft Tissue Neoplasms | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Esophageal Diverticulum | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Colonic Malignant Neoplasms | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Biliary Tract Gallstones | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Rectal Malignant Neoplasms | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hiatal Hernia | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Others | 2 | 2 | 4 |

Staff cost and loss of productivity costs in each assigned group.

| Conventional face-to-face Group | Follow-up Telemedicine Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Staff cost | ||

| Physician | 3029,96€ | 3029,96€ |

| Nurse | 2100,21€ | 0€ |

| Nursing assistant | 1409,84€ | 0€ |

| Administrative officer | 1600,1€ | 1600,1€ |

| Loss of productivity costs | ||

| Patient’s productivity loss | 95,6€ (8 h) | 11,95€ (1 h) |

| Caregiver’s productivity loss | 95,6€ (8 h) | 0 |

Patient’s characteristics in each group of study.

| Conventional face-to-face Group | Follow-up Telemedicine Group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 49,8 yo | 50,3 yo | P = .8361 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 59 (59%) | 53 (53%) | P = .3932 |

| Female | 41 (41%) | 47 (47%) | |

| ASA Score | |||

| ASA I-II | 86 (86%) | 88 (88%) | P = .2322 |

| ASA III-IV | 14 (14%) | 12 (12%) | |

| Interval from discharge to follow-up | |||

| Less than 2 weeks | 6 (6%) | 13 (13%) | P = .1692 |

| Between 2 and 4 weeks | 63 (63%) | 62 (62%) | |

| Between 4 and 6 weeks | 27 (27%) | 20 (20%) | |

| Between 6 and 8 weeks | 1 (1%) | 4 (4%) | |

| More than 8 weeks | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Length of visit (n = 164) | |||

| Less than 5 min | 15 (17%) | 16 (22%) | P = .1532 |

| Between 6 and 10 min | 36 (40%) | 38 (51%) | |

| Between 11 and 20 min | 32 (35%) | 18 (24%) | |

| More than 20 min | 7 (8%) | 2 (3%) | |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists.

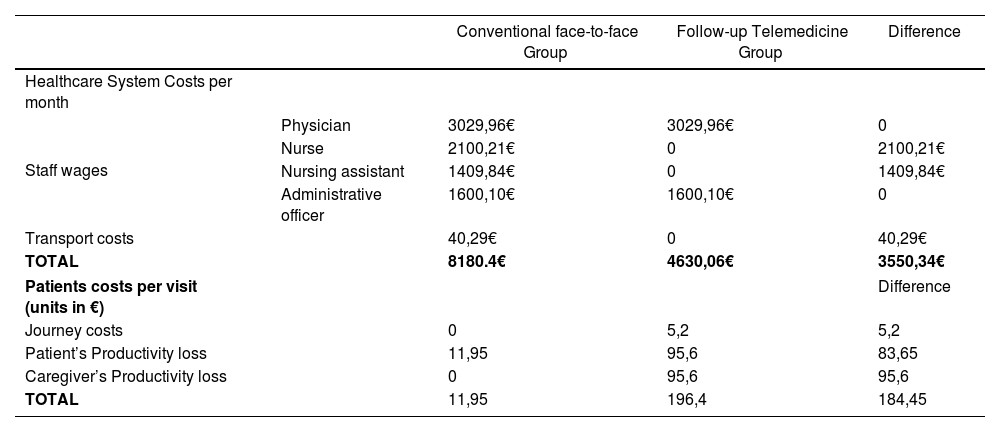

After collecting the data related to the economic area the results were divided by medical institution and patient. Table 5 presents the costs for the medical institution (staff cost and ambulances) comparing the TM group vs. the conventional follow-up. In a survey carried out after the visits, none of the patients in the conventional follow up used ambulance but, in the TM group, 4 patients would have used it for medical reasons. Table 5 also shows the costs for the patients, which are transport and loss of productivity. The survey revealed that patients in the conventional follow up used its own car to reach the hospital. The average cost per journey was 2,6€ (5,2€ go and return). This table also shows the loss of productivity due to job absenteeism.

Healthcare System Costs and patients costs per visit (units in €) per month according to study group.

| Conventional face-to-face Group | Follow-up Telemedicine Group | Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare System Costs per month | ||||

| Staff wages | Physician | 3029,96€ | 3029,96€ | 0 |

| Nurse | 2100,21€ | 0 | 2100,21€ | |

| Nursing assistant | 1409,84€ | 0 | 1409,84€ | |

| Administrative officer | 1600,10€ | 1600,10€ | 0 | |

| Transport costs | 40,29€ | 0 | 40,29€ | |

| TOTAL | 8180.4€ | 4630,06€ | 3550,34€ | |

| Patients costs per visit (units in €) | Difference | |||

| Journey costs | 0 | 5,2 | 5,2 | |

| Patient’s Productivity loss | 11,95 | 95,6 | 83,65 | |

| Caregiver’s Productivity loss | 0 | 95,6 | 95,6 | |

| TOTAL | 11,95 | 196,4 | 184,45 | |

Overall, for a Healthcare provider in Spain, it is at least 3.550,34€/month more expensive to keep a conventional doctor’s office operational than a TM one. Costs of medical transport (ambulances) should be added depending on the needs. For the patient and the caregiver, this difference is 184,45€ per visit, taking loss of productivity into account.

DiscussionTM is a tool that has had a relevant impact recently, not only because an improvement of the internet connectivity and an evolution of the cell-phones but also because of the Covid19 pandemic. In a previous study, we demonstrated that TM was feasible as an alternative for patients’ follow-up in a General Surgery department. It was safe and patients were satisfied with this new service. Although we included elderly people, this was not a problem to use TM.14 Nevertheless, an economic evaluation was needed. In the literature there was a lack of consensus about the economic impact of TM as a result of a scarcity of randomized studies, the lack of long term assessments, small sample sizes and the variability in the way the costs are calculated.1,26 In fact, only 20% of the studies about TM contain quantitative costs data28 and therefore, it is difficult to make comparisons among them.

Mistry et al.29 carried out a systematic review, showing that some studies couldn’t prove that TM was cost-effective compared to conventional follow up. That was because some of them were pilot studies and others didn’t take into consideration the indirect costs or the real costs of a regular service. Michaud group also found a lack of detailed data on programs’ costs in their systematic review.1 Although all the studies indicated that TM could reduce costs, there was not enough evidence to recommend it.

In favor of TM, Zholudev et al., in its cost analysis of teleurology vs conventional follow up, found that there were savings in the TM group for both the Health System and the patient.5 He also reported lower no-show rate in the TM group. Wang et al., in his assessment about the implementation of a TM program in China, mentions that it was more cost-effective for patients and care-givers than for the Health System, due to the lack of travels and an easier access. The government also avoided extra-costs to enhance sanitary infrastructures, resources and specializes doctors in remote areas.3

However, on the other hand, Ashwood et al., in his economic evaluation about TM, suggested that it could be cost-ineffective due to an easy access of patients to medicine professionals causing visits that are not justified.30 Stensland et al. also reports in his study a higher consultation rate of specialized doctors in the TM in comparison to the conventional follow up. He also points out that cost savings fall to both patients (from lower travel costs) and employers (from improved employee productivity).31 In the same way, Jackson et al. indicates in his systematic review of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases that, although TM seems to involve less expenses due to salary savings, an initial extra budget is needed to implement it and that there are recurrent expenses to maintain and enhance the program.32

In our study about TM costs we considered a social point of view, as it could have an impact in the healthcare economic field (less staff or ambulances needed), in the individual economic field (avoiding expenses and time to reach the hospital) and in the social field (avoiding loss of working hours or productivity for both the patient and the caregiver). This study shows that TM, although it requires an initial investment, is cost-effective for both the medical institution and for the patient/caregiver in the long term. Regarding the Medical institution, depending on the country’s wages, the savings may be more or less important and could even be negligible. But from a patient and a social point of view savings are clear, as it involves direct expenses due to transportation and indirect expenses due to loss of productivity. Nevertheless, a conscious and well-informed population is needed to assure a proper use of this service. However, given the short term analyzed in this study, it would be necessary to continue a cost assessment when the service comes into routine use.

Ours study is one of the scarce RCTs demonstrated the clinical feasibility and patient acceptance of TM for outpatient follow-up after discharge. However, ours study also has some limitations. First, sample size, even calculated, is relatively small and the heterogeneity of the group of patients included somewhat detracts from the value of the study since the needs for care in outpatient clinics in the postoperative period vary depending on the surgical procedure. We made the decision to include different patients to adapt to the reality of a General Surgery service. In future studies, it could be considered to include patients with more homogeneous surgeries or with areas of specialization (for example, colorectal surgery). Moreover, the costs need to be compared to the benefits as much as possible on the individual patient level and in our experience this cost-benefit analysis lacks a number of costs measured on the individual patient level. In addition measurement of these costs is in some parts incomplete as staff costs, loss or productivity, transport costs and installation and software development are mentioned, but are representative of them in our country and specific university hospital. In addition, and specifically, the amortization of computer equipment and software was not included in this economic study. We considered that the complexity of obtaining all this data did not justify the minimal difference that could exist in the final result and therefore we did not include it in the overall statistical analysis.

There is evident the telemedicne (TM) it is a new paradigma to follow-up patients after hospital discharge in post pandèmics era. In our initial experience with the economical analysis of a RCT, TM seems a cost-effective service from a social point of view to follow general surgery patients. Thus we are planning a large study with a detailed economical analysis in the next future.

FundingThis research did not received any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declared that they have no any conflicte of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ferret G, Cremades M, Cornejo L, Guillem-López F, Farrés R, Parés D, et al. Impacto económico del seguimiento ambulatorio mediante telemedicina vs. visita presencial a pacientes de cirugía general: un análisis secundario de un ensayo clínico aleatorizado. Cir Esp. 2024.