The etiological spectrum of infectious agents capable of causing infective endocarditis (IE) is very broad. In this review, we aim to provide readers with an overview of the main “uncommon or rare” agents responsible for endocarditis, as well as some IE pathogens that are particularly challenging to diagnose due to their difficulty in culture. Specifically, we present detailed information on Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella spp., Tropheryma whipplei, Brucella spp., and Mycobacterium spp. endocarditis. We also address the potential role of viruses as etiological agents of IE and summarize other uncommon causes in a comprehensive table.

El espectro etiológico de los agentes infecciosos capaces de causar endocarditis infecciosa (IE) es muy amplio. El objetivo de esta revisión panorámica es ofrecer a los lectores una visión general de las IE provocadas por «agentes poco comunes o raros» que pueden ser difíciles de diagnosticar por su difícil cultivo. Concretamente, se presenta información detallada sobre la endocarditis causada por Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella spp., Tropheryma whipplei, Brucella spp. y Mycobacterium spp. También se aborda el posible papel de los virus como agentes etiológicos de IE y en una tabla se detallan otras causas poco comunes de IE.

It is very difficult to define what constitutes an infective endocarditis (IE) caused by uncommon pathogens, as “uncommon” is a highly relative term, not recognized in the medical literature, and it depends on multiple variables. The literature does refer to IE caused by rare pathogens such as endocarditis caused by anaerobic bacteria, which is uncommon and primarily affects prosthetic valves1, or endocarditis caused by non-HACEK gram-negative bacilli, which are mostly related to endovascular devices and contact with the healthcare system2.

The etiological spectrum of infectious agents capable of causing IE is very broad. In fact, related to a single case, one can find hundreds of bibliographic references. Virtually any bacterium has the potential to colonize the vascular endothelium and, under certain conditions, cause IE. Nevertheless, some IE agents are more common than others are.

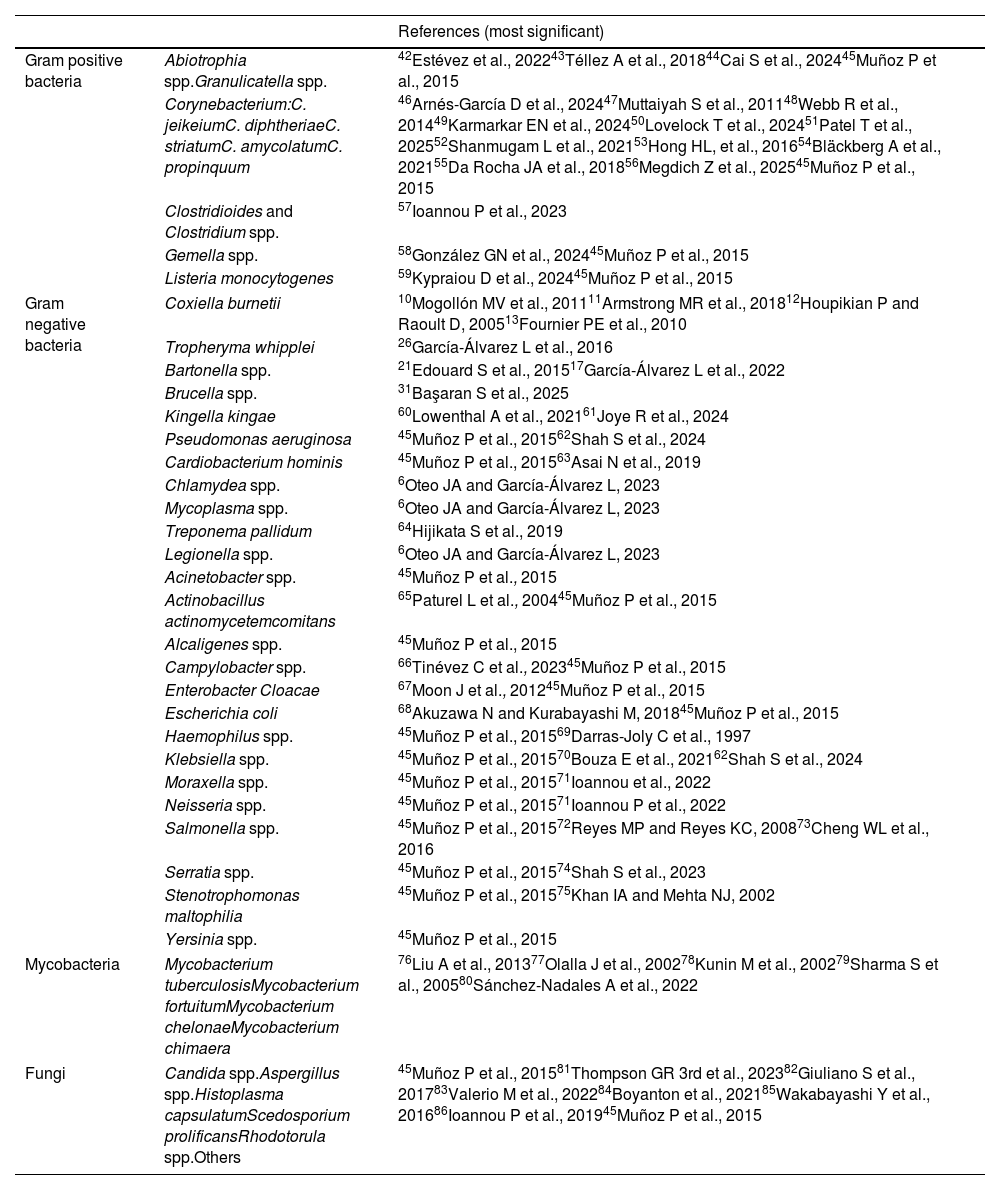

The agents listed in Table 1 are considered uncommon not only because they represent a very small proportion of the total cases but also because they are associated with specific predisposing conditions (immunosuppression, intravenous drug use, zoonotic exposure) and/or their diagnosis may be difficult requiring special techniques such as specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR), serology, prolonged incubation times, or specific culture conditions. One example would be fungal endocarditis. There are predisposing factors (prolonged hospitalizations, extended use of antibiotics, permanent central venous catheters, or cardiac surgery) that are associated with its development. In the hospital setting, different species of Mycoplasma or Legionella can cause postoperative infectious endocarditis, and contact with mammals or birds can be a source of infection with Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetii or Chlamydiapsittaci.3

Main uncommon pathogens involved in endocarditis.

| References (most significant) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gram positive bacteria | Abiotrophia spp.Granulicatella spp. | 42Estévez et al., 202243Téllez A et al., 201844Cai S et al., 202445Muñoz P et al., 2015 |

| Corynebacterium:C. jeikeiumC. diphtheriaeC. striatumC. amycolatumC. propinquum | 46Arnés-García D et al., 202447Muttaiyah S et al., 201148Webb R et al., 201449Karmarkar EN et al., 202450Lovelock T et al., 202451Patel T et al., 202552Shanmugam L et al., 202153Hong HL, et al., 201654Bläckberg A et al., 202155Da Rocha JA et al., 201856Megdich Z et al., 202545Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Clostridioides and Clostridium spp. | 57Ioannou P et al., 2023 | |

| Gemella spp. | 58González GN et al., 202445Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 59Kypraiou D et al., 202445Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Gram negative bacteria | Coxiella burnetii | 10Mogollón MV et al., 201111Armstrong MR et al., 201812Houpikian P and Raoult D, 200513Fournier PE et al., 2010 |

| Tropheryma whipplei | 26García-Álvarez L et al., 2016 | |

| Bartonella spp. | 21Edouard S et al., 201517García-Álvarez L et al., 2022 | |

| Brucella spp. | 31Başaran S et al., 2025 | |

| Kingella kingae | 60Lowenthal A et al., 202161Joye R et al., 2024 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 45Muñoz P et al., 201562Shah S et al., 2024 | |

| Cardiobacterium hominis | 45Muñoz P et al., 201563Asai N et al., 2019 | |

| Chlamydea spp. | 6Oteo JA and García-Álvarez L, 2023 | |

| Mycoplasma spp. | 6Oteo JA and García-Álvarez L, 2023 | |

| Treponema pallidum | 64Hijikata S et al., 2019 | |

| Legionella spp. | 6Oteo JA and García-Álvarez L, 2023 | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | 65Paturel L et al., 200445Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Alcaligenes spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Campylobacter spp. | 66Tinévez C et al., 202345Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Enterobacter Cloacae | 67Moon J et al., 201245Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Escherichia coli | 68Akuzawa N and Kurabayashi M, 201845Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Haemophilus spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 201569Darras-Joly C et al., 1997 | |

| Klebsiella spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 201570Bouza E et al., 202162Shah S et al., 2024 | |

| Moraxella spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 201571Ioannou et al., 2022 | |

| Neisseria spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 201571Ioannou P et al., 2022 | |

| Salmonella spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 201572Reyes MP and Reyes KC, 200873Cheng WL et al., 2016 | |

| Serratia spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 201574Shah S et al., 2023 | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 45Muñoz P et al., 201575Khan IA and Mehta NJ, 2002 | |

| Yersinia spp. | 45Muñoz P et al., 2015 | |

| Mycobacteria | Mycobacterium tuberculosisMycobacterium fortuitumMycobacterium chelonaeMycobacterium chimaera | 76Liu A et al., 201377Olalla J et al., 200278Kunin M et al., 200279Sharma S et al., 200580Sánchez-Nadales A et al., 2022 |

| Fungi | Candida spp.Aspergillus spp.Histoplasma capsulatumScedosporium prolificansRhodotorula spp.Others | 45Muñoz P et al., 201581Thompson GR 3rd et al., 202382Giuliano S et al., 201783Valerio M et al., 202284Boyanton et al., 202185Wakabayashi Y et al., 201686Ioannou P et al., 201945Muñoz P et al., 2015 |

Mycobacteria can also be cause of endocarditis4. For example, Mycobacterium chimaera has been linked to contamination of heater-cooler devices used during open-heart surgeries and overall that manufactured by a determinate commercial system which released aerosols contaminated5.

Another factor to consider regarding these IE caused by rare microorganisms is the fact that many of the reported IE cases could be dismissed as endocarditis attributed to these agents. This is the case with endocarditis caused by Chlamydia spp., in which the number of published cases confirmed by direct techniques is practically negligible6,7.

An interesting factor to consider is the diagnostic criteria for IE. For instance, the 2023 ISCVID criteria demonstrated greater sensitivity than both the 2015 and 2023 Duke-ESC criteria in detecting IE caused by newly recognized microorganisms8. This increased sensitivity also led to a higher number of cases being classified as ‘possible IE,’ rather than confirmed. Also, changes in the nomenclature of infectious agents may seem that some agents are less common, but really, the two names can coexist for a time. An example could be the case of the now designated Streptococcus tigurinus that is a subspecies from Streptococcus oralis (S. oralis subsp. tigurinus)9.

This overview review will focus on peculiar characteristics of the “main infectious agents” that cause uncommon IE in our environment, considering “uncommon pathogens” those microorganisms that are isolated in a significantly lower number of cases compared to the typical agents (Staphylococcus aureus, viridans group streptococci, Enterococcus spp., etc.) and are cause of blood culture negative endocarditis (BCNE). In addition, we have reviewed the role of virus as etiological agents of IE. We excluded other uncommon etiological agents of IE, as the presence of an infectious agent in blood cultures, especially in a patient with cardiac findings, vascular complications, persistent fever, or predisposing cardiac conditions should always alert clinicians to the possibility of IE.

Uncommon pathogens causing endocarditisCoxiella burnettiWorldwide distributed, C. burnetti, is the main agent in our media of BCNE. Extensive case series, predominantly from Europe, have been reported10–14. Transmission generally occurs through exposure to infected fluids from mammals, via aerosols, consumption of contaminated dairy products (particularly milk), or direct placental contact-especially from species such as sheep and goats. However, the pathogen can also be carried by the wind over long distances, and patients may be unaware of any relevant epidemiological exposure. Patients infected with C. burnetii (the agent of Q fever) may develop chronic or persistent forms of the disease, such as IE, particularly when predisposing factors are present or if the infection is not properly treated. The clinical presentation of Q fever endocarditis can resemble that of other forms of IE, although it typically follows a subacute course, predominantly affects the left side of the heart, and most commonly involves the aortic valve. Fever is present in approximately two-thirds of cases, usually well tolerated and of low grade. Most patients have predisposing conditions, such as valvular abnormalities or a prosthetic valve. Embolic events tend to be less frequent, and vegetations are usually smaller than those observed in IE caused by more common pathogens. Diagnosis requires demonstration of the pathogen through PCR or culture of blood, affected tissue, or an implanted device, or the presence of phase I IgG antibodies by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) at a titre greater than 1:800. Cross-reactivity in serological testing must be considered, particularly with Chlamydia spp. and Bartonella spp. Treatment is prolonged and typically involves a combination of doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine. In cases involving infected prosthetic material or devices, surgical removal is recommended. Relapses occur in approximately 8% of cases, and mortality rates range from 5% to as high as 60%10,14–16.

Bartonella spp.The incidence of bartonella endocarditis varies among countries. In Europe, Bartonella spp. account for 0–4.5% of the infective endocarditis17, however, in certain areas of Africa it reaches 15%18,19. Nevertheless, the prevalence of this condition could be underestimated due to the difficulties involved in its identification and because to diagnose bartonella endocarditis is difficult since the clinical presentation is not typical. Cardiac failure is the main presenting form, while fever is observed in less than half of the cases. Other IE typical signs, such as embolic events, are uncommon. The age of presentation observed is also lower than in the endocarditis caused by the “usual agents”.17 At least eight Bartonella spp. have been involved in infective endocarditis, with Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana accounting for more than 99% of the cases. B. quintana has been reported as causative agent of IE in approximately 75% of the cases, while B. henselae occurs in around 25%20. These data differs from the Spanish series where B. quintana accounts for almost 40% of the cases and the remaining are due to B.henselae17. The infection is contracted by cat-scratch or exposure to its fleas in the case of B. henselae, and body lice for B. quintana. Anyway, in some patients we have not identified epidemiological known risk factors17. The most affected valve is the aortic and half of the cases showed preexisting valvular abnormalities (more than 40% of the cases, reaching 62.5% of the patients with B. quintana IE)17,21. Most patients needed surgery because the diagnosis of bartonella endocarditis was often made late, and early treatment was not always given (in the Spanish series surgery was performed in 76.2%). In this series, neurological or cardiac sequelae were present in 14.3% of patients and no relapses were observed17. First reports showed high mortality rates (7–30%), however recent data indicate that mortality has decreased to around 7%, thanks to better diagnosis and treatments17. Molecular techniques are currently considered the most effective tools for diagnosing BCNE17,22. Although serological tests—particularly IFA—are still recommended in current guidelines, several studies have shown a poor correlation with the established IgG cutoff value of ≥800.23 Additionally, the high degree of serological cross-reactivity between Bartonella, Chlamydia/Chlamydophila, and C. burnetii can further complicate the diagnosis. Cross-reactivity among different Bartonella species also makes it difficult to identify the specific species involved in a given case of IE17,24. Another important consideration is the high proportion of asymptomatic individuals infected with Bartonella spp., which may hinder accurate diagnosis25.

Tropheryma whippleiT. whipplei, the agent of Whipple disease, is responsible for IE in 0.6–3.5% of cases of BCNE12,13,26. Besides, it does not present with the typical signs and symptoms, making its diagnosis quite challenging. Because of this, its incidence may be underestimated. In our experience, the main clinical manifestation of IE caused by T. whipplei is heart failure, which is present in three-quarters of the patients, while fever has been documented in only 35%, and embolic phenomena in less than 6% of the PAS the presence of chronic arthralgias are present until 35–75% of the cases and is one the main features that can precede the diagnoses for years26. It is worth highlighting that only 12% of patients also presented classic Whipple's disease26. Although T. whipplei can be cultured, the diagnosis of IE due to T. whipplei is primarily performed by molecular analysis of the valves26. Diagnosis can also be established by immunohistochemistry and PAS staining. The use of specific molecular targets is recommended, due to the limited sensitivity of broad-range PCR techniques27–29. According to the latest European guidelines of IE of the ESC, the recommended treatment is doxycycline combined with hydroxychloroquine for at least 18 months23. However, treatment regimens of at least 12 months have also shown effectiveness30. Given the atypical presentation of this form of endocarditis, T. whipplei should be considered and investigated in all cases of heart failure undergoing surgery.

Brucella spp.Brucella melitensis has been an important etiological agent of IE in the world for many times, but hygienization and cattle vaccines has improve the situation. It is a rare but serious complication of brucellosis (1–2% of cases). With some exceptions, European countries are free of brucellosis, but it is still present in incoming countries. The main source of infection is the consumption of dairy products or contact with placentas, not overlooking laboratory accidents. B. mellitensis usually affects native valves, especially the aortic valve, as well as prosthetic valves and electronic devices. It has an insidious course, with prolonged systemic symptoms such as undulating fever, sweating, and weight loss, which delays diagnosis. Brucella IE is characterized by extensive valvular destruction and the formation of perivalvular abscesses31. It should be considered in patients with endocarditis from endemic areas who have epidemiological exposure to the agents. Brucella spp. grow best in clinical samples (blood, affected tissues) processed in specific media and in prolonged incubation blood cultures. It can be amplified using molecular techniques such as PCR in blood and affected tissues. Serology remains a useful tool when these techniques are not available or in cases of BCNE16. Treatment combines prolonged antibiotics with high intracellular penetration and early surgery in most cases. This endocarditis still has a high mortality rate31.

Mycobacterium spp.Mycobacterial endocarditis is a rare but clinically significant entity. Mycobacteria can be either tuberculous or non-tuberculous; however, Mycobacterium spp. responsible for endocarditis are predominantly rapidly growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and Mycobacteriumneoaurum.32 These infections are usually associated with prior invasive procedures, such as cardiac surgeries or catheterizations, and can affect both native and prosthetic valves. On the other hand, tuberculous endocarditis is extremely rare and generally occurs in the context of miliary tuberculosis or immunosuppression5.

Mycobacterial endocarditis typically has a subacute course with nonspecific symptoms, making diagnosis challenging. Conventional blood cultures are often negative due to the slow growth or special culture requirements of these pathogens, so it is essential to employ specific culture techniques and molecular biology methods for the detection4.

Treatment of mycobacterial endocarditis is complex because of the intrinsic resistance of mycobacteria to many conventional antibiotics. It requires prolonged, combination antimicrobial therapy based on sensitivity testing, which may include amikacin, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, and cefoxitin33. Surgical intervention for device removal or valve replacement is common. The prognosis remains serious, with a high mortality rate, particularly in cases where diagnosis is delayed or treatment is suboptimal.

An interesting chapter is that related to M. chimaera. It has been identified as an emerging pathogen linked to serious infections after open-heart surgery, especially in patients with prosthetic heart valves or vascular grafts. Since 2011, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported estimable number cases of invasive infections caused by M. chimaera in patients across European countries. All had a history of cardiothoracic surgery and was related with the heater-cooler units34 (LivaNova 3T™ Heater-Cooler System, formerly Stöckert 3T Heater-Cooler System). Since this connection was identify the number of cases has significantly decreased, however, due the long incubation period of M. chimaera (two to more than five years), “late” cases continue to occur in patients who underwent surgery before the problem was corrected.

In summary, mycobacterial endocarditis, although rare, can be a serious complication and requires a high index of suspicion, particularly in cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis or in patients with persistent systemic symptoms and negative cultures. Management includes both specific antimicrobial therapy and surgical interventions when necessary.

Viral endocarditisIt is well established that the development of infective endocarditis typically requires prior damage to the cardiac endothelium, which may be facilitated by inflammatory processes such as viral infections. However, the evidence regarding viral endocarditis remains limited, and further research is needed to fully understand its pathogenesis and management35.

Infective endocarditis are primarily caused by bacteria and, to a lesser extent, by fungi. However, documented cases of viral endocarditis do exist. Until 2011, virus-induced IE had been described only in animal models, but Blumental et al. published a case of a 4 month-old 21-trisomic boy with congenital atrioventricular septal defect experienced three episodes of dehiscence of his prosthetic patch, attributed to IE36. The patient presented with heart failure but did not exhibit fever or inflammatory syndrome. Virus Coxsackie B2 was isolated from a cardiac prosthetic patch suggesting a viral aetiology in a culture-negative endocarditis36. There is also a reported case of an immunocompromised patient due to HIV and other conditions in which IE is attributed to CMV37. Additionally, it has been published that SARS-CoV-2 could be related to the development of endocarditis, either directly through active infection or indirectly via a post-infectious immune response, as this virus has demonstrated the capacity to affect both intact and previously damaged cardiac tissue38,39. However, these cases are highly debated40, and it is expected that with the incorporation of new diagnostic techniques, the debate reopened during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic will be clarified38.

Regarding giant viruses, although they have been associated with cardiac pathologies such as myocarditis, their role as causative agents of endocarditis has not been demonstrated41.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve the language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.