The pericardium is a double-walled sac that contains the heart and the roots of the large vessels. It fixes the heart to the mediastinum and provides protection against infections from adjacent organs and tissues.

Pericarditis is a common disease in clinical practice. It causes 0.1% of all hospital admissions and 5% of emergency room admissions for chest pain. In general, the etiology of pericarditis can be classified into non-infectious and infectious causes, whether of viral, bacterial, fungal, tuberculous, or even parasitic etiology, the most common cause being viral etiology. Purulent pericarditis represents less than 1% of bacterial pericarditis, which is commonly caused by Staphylococci, Streptococci, and Pneumococci; and is associated with high mortality, so its timely approach is important.1,2

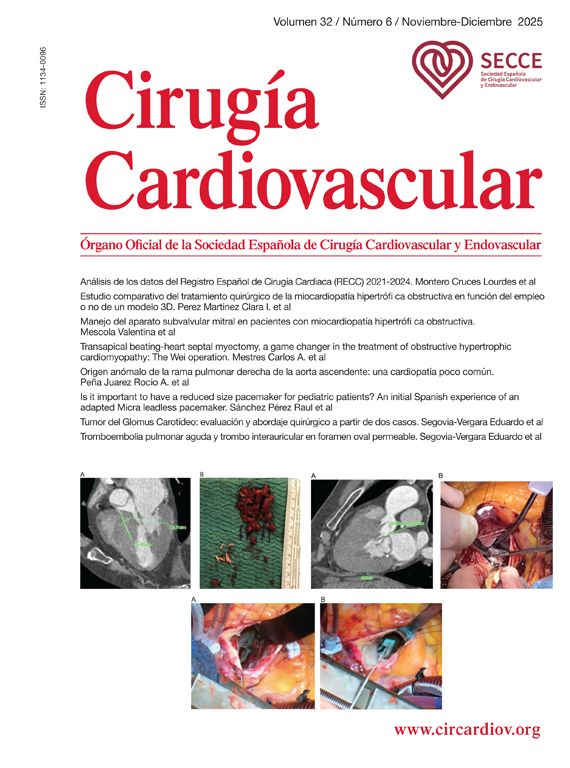

Case reportA 63-year-old male with arterial hypertension, who two years ago underwent an open cholecystectomy complicated by perforation of the gallbladder sac, was treated without apparent complications. During his follow-up with cholangio MRI, we found a 27 cc subphrenic collection adjacent to the IVa hepatic segment, which was treated with antibiotics because of its small size (Fig. 1).

Two weeks later, the patient arrived with transient chest pain, radiated to the back and abdomen, and was accompanied by diaphoresis and dyspnea on minor exertion. The physical examination revealed drowsiness, Beck's triad, tachycardia, and tachypnea. (Hemodynamically unstable patient who required vasoactive drugs.)

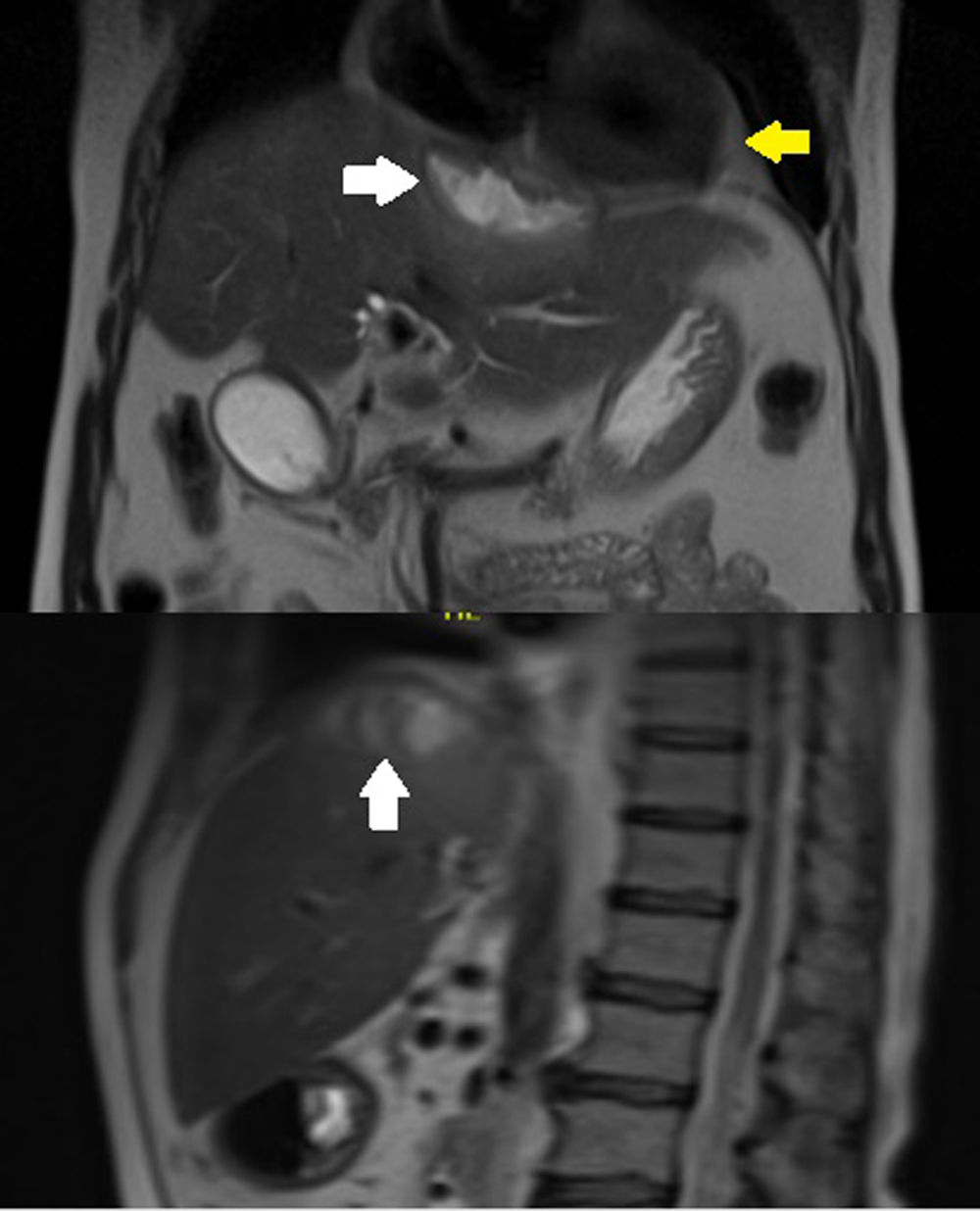

The laboratory tests showed increased urea and creatinine levels; leukocytosis: 41,400cells/μL; neutrophils: 92%; mixed acidosis, and hyperlactatemia. The electrocardiogram showed electrical hypovoltage and the echocardiogram revealed severe pericardial effusion with the collapse of the atrium and right ventricle (Fig. 2).

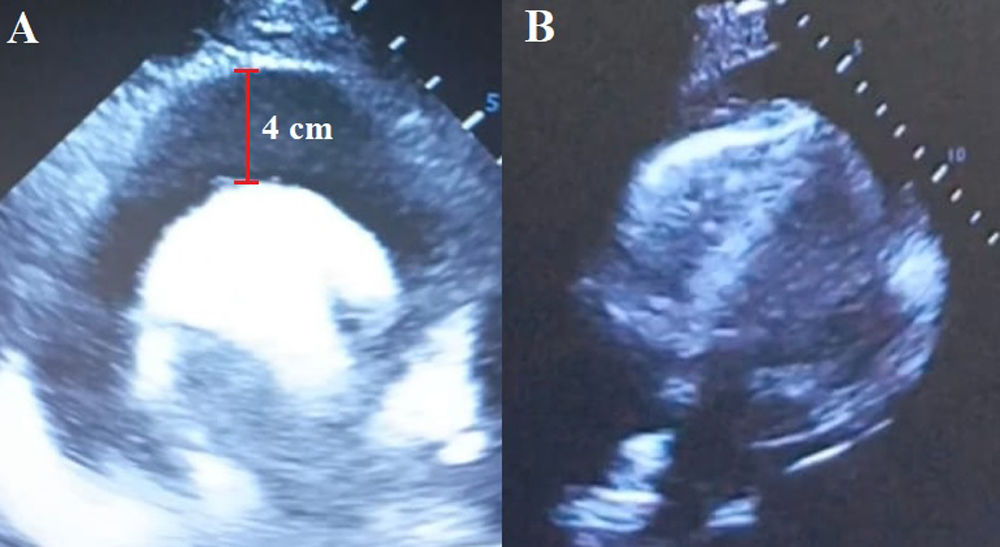

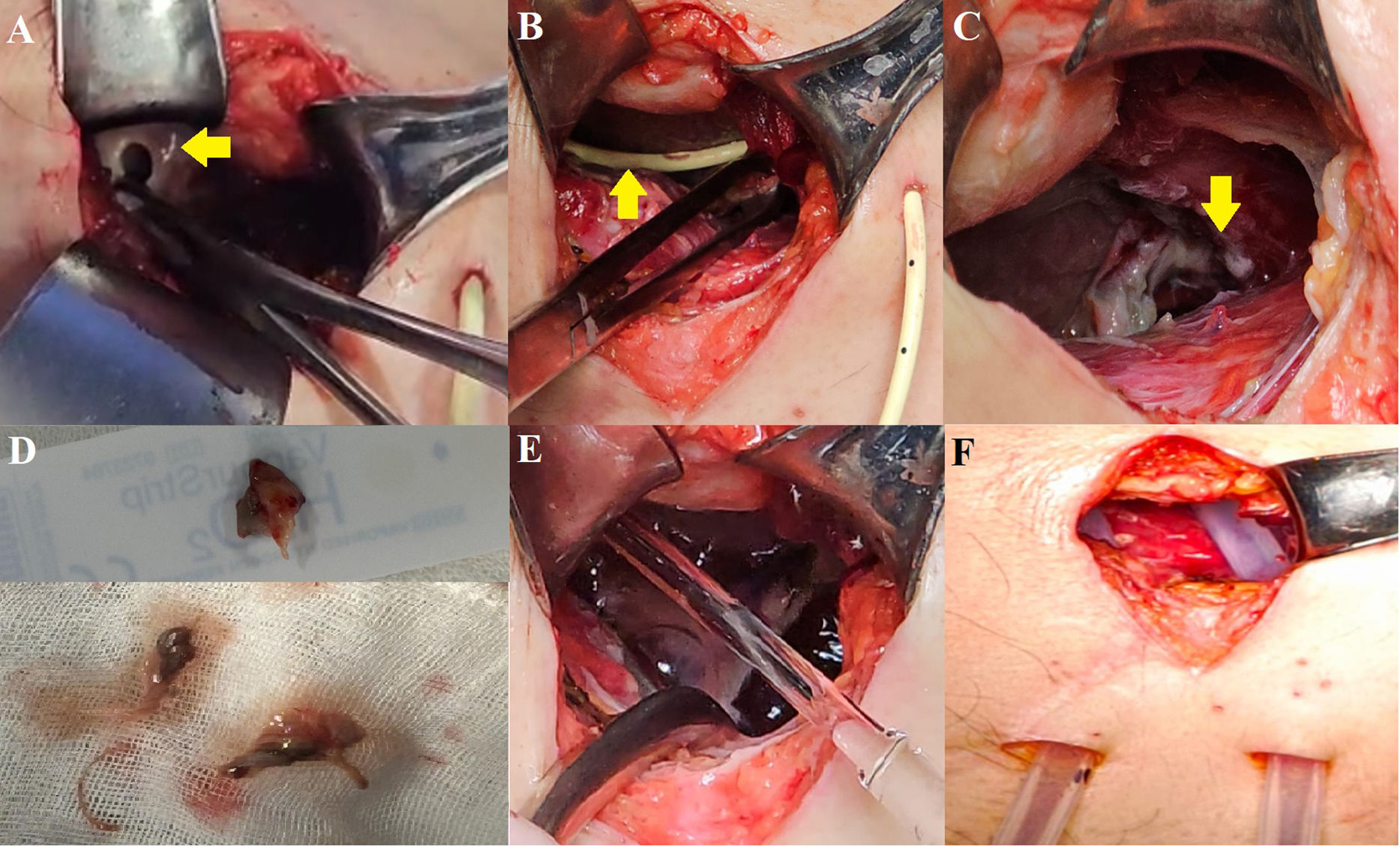

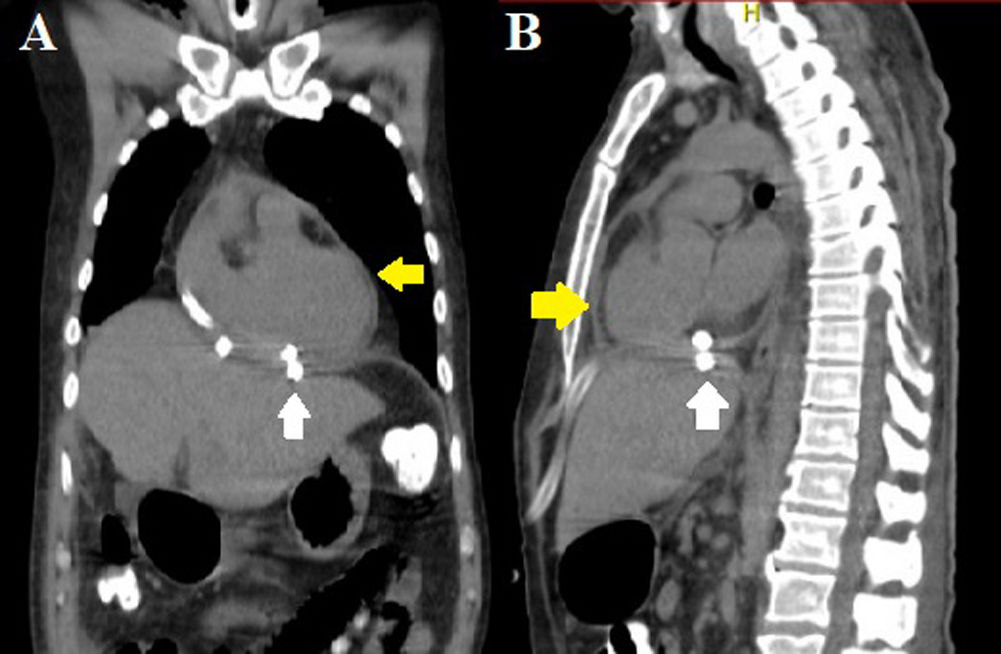

Hence, subxiphoid pericardiocentesis guided by ultrasound was performed, obtaining 1100 cc of purulent, foul-smelling fluid (Fig. 3). After the pericardiocentesis, blood pressure improved and vasoactive drugs were lowered. The airway was secured and connected to invasive mechanical ventilation. Vancomycin and imipenem were initiated empirically. Then, a control tomographic study was performed (Fig. 4). Based on the findings, a subxiphoid pericardial window was created (Fig. 5). Through this approach, the subphrenic abscess measuring approximately 20cc was drained. The parietal pericardium was friable and thickened to 2mm, with remnants of fibrin membranes. Pericardial cavity lavage was performed, and 2 drains were placed: one in the pericardial cavity and another in the subphrenic abscess.

(A) Simple CT of the chest showing residual pericardial effusion (white arrows) and pericardiocentesis catheter in the pericardial cavity (yellow arrows). (B) Subphrenic collection measuring 8cm×3cm×2cm with an estimated volume of 25cc (white arrow). Catheter in the pericardial cavity (yellow arrow). (C) Thinning of the diaphragm at the level of the collection and pericardial sac with apparent fistulous tract.

(A) Opening of parietal pericardium (yellow arrow). (B) Catheter in pericardial cavity (yellow arrow). (C) Subphrenic abscess with lysis of the fibrous portion of the diaphragm. (D) Parietal pericardium and fibrin membranes. (E) Lavage of the cavity with saline solution. (F) Placement of 24Fr Kardiaspiral type probes.

The sample of the pericardial fluid was exudative and the culture developed Morganella morganii, sensitive to meropenem. After surgery, a CT scan showed a decrease in pericardial effusion and the absence of the subphrenic collection (Fig. 6). The patient remains under outpatient follow-up, and a control CT scan will be requested in 6 months due to the risk of diaphragmatic hernia.

DiscussionPurulent pericarditis (PP) accounts for less than 1% of all cases of pericarditis, and the associated mortality rate is 20–30%.1,2 Poor prognostic factors include the presence of cardiac tamponade, septic shock, delayed pericardial drainage, infection by Staphylococcus aureus or gram-negative bacilli, and malnutrition.3

There are several mechanisms for its development. Primary infection, i.e. infection of a myocardial focus, is very rare. It usually occurs due to the migration of germs to the pericardial sac from a preexisting septic focus, which may be intrathoracic or subdiaphragmatic, or through direct infection by trauma or thoracic surgery, as well as hematogenous dissemination.1,3–5 This case is classified as type V due to its origin, according to the bibliography reviewed.2

The most frequent germs are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia and Pneumococci. Less frequently, Bacteroides, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and even M. morganii have been reported.1,6,7 Polymicrobial purulent pericarditis has a very low incidence and is associated with complicated abdominal surgical procedures, neoplasias of the digestive tract, diabetes mellitus, and HIV infection. Gram-negative and anaerobic bacilli have been identified in pericardial-digestive fistulas.6

M. morganii is an anaerobic gram-negative organism, that is part of the intestinal flora and very rarely causes human infections. Pericarditis caused by M. morganii is extremely rare. There are few publications, and most of them are associated with immunosuppression due to underlying pathologies.8,9 In this case, the origin is an abdominal septic focus.

The clinical manifestation of PP can be nonspecific. Patients can present with chest pain, dyspnea, and even signs of cardiac tamponade, such as Beck's triad. Imaging studies such as echocardiograms continue to be one of the best techniques to corroborate the presence or absence of pericardial effusion. The diagnosis is confirmed through a study of pericardial fluid.2,3

The management of purulent pericarditis involves several aspects, including adequate antibiotic coverage and hemodynamic and ventilatory support as required. The main goal is to drain the pericardial cavity and identify and eradicate the origin of the infection.

Among the complications associated with PP, persistent pericarditis can lead to constriction (up to 57% in the long term), endocarditis, bacteremia, or mycotic aneurysms.2,3

Pericardiocentesis evacuation is a Class I-C recommendation for the diagnosis of PP. If it's performed in an early stage, it improves the prognosis by decreasing hemodynamic instability and preventing cardiac tamponade. When purulent pericarditis is confirmed, empirical antibiotics should be started to cover S. aureus and gram-negative bacteria.1–3

Compared to other cases that used only one antimicrobial, the treatment in this case was started with carbapenems and glycopeptides considering the septic shock of this patient, followed by ciprofloxacin for 30 days. The antimicrobial regimen is now based on bacterial sensitivity to eradicate the infection and prevent recurrences.2,3

Simple drainage and pericardiectomy have been compared, and the latter is associated with greater prevention of constrictive pericarditis. Surgical techniques include the implantation of a subxiphoid drainage tube, a pericardial window (pleural or subxiphoid), and partial interphrenic or complete pericardiectomy.2,3

Comparing the management of reported cases where pericardiectomy and lavage of the cavity were the first step, in this case, a pericardiocentesis was performed to resolve cardiac tamponade. Once hemodynamic stability was reached, a subxiphoid pericardial window was created. Through this incision, the pericardial cavity was drained, and given the lysis of the diaphragm, the abdominal cavity was accessed to drain the subphrenic abscess. Two drains were placed, directed to each space respectively.

Despite the associated surgical mortality of up to 8%, pericardiectomy and pericardial windows are indicated when dense adhesions, encapsulated purulent effusion, recurrence of tamponade, persistent infection, or constrictive pericarditis are found. Surgical mortality is associated with adhesions to adjacent tissues and organs, and the poor hemodynamic state of the patient.2,10

Persistent PP contributes to the formation of adhesions and loculation of the effusion by fibrin clots, which prevent the complete evacuation of pus through the drains, increasing the risk of death due to septic shock or tamponade. Fibrin is the main cause for the development of persistent PP, which justifies surgical intervention to decrease the risk of developing constrictive pericarditis secondary to chronic inflammation.2

There is a less invasive treatment alternative to surgery: fibrinolysis. It is aimed at avoiding the formation of fibrin and adhesions, and preventing persistent and constrictive pericarditis. The first reports of success date back to 1951 and 1984 in patients with persistent PP despite pericardiectomy and antibiotics. Experimental studies in animals have documented the absence of histological changes in the pericardium. In humans, studies have not been conclusive and, although the use of fibrinolytics can “liquefy” the purulent exudate, the European Society of Cardiology recommends surgical drainage.2

It has not been established whether the best time for fibrinolysis is after the insertion of the drain or in the event of recurrence or incomplete evacuation of pus. Fibrinolytics can dissolve the fibrin that is predominant in the first week, but they do not dissolve the fibrosis that usually appears after the second week.2 Fibrinolysis was not considered because the pericardial drainage presented serous secretion and was removed when drainage output was less than 50ml in 24h.

ConclusionsThe management of PP includes several aspects, from adequate antibiotic coverage to drainage of the pericardial cavity. Early diagnosis and treatment reduce mortality significantly, considering that most patients arrive presenting with cardiac tamponade.

Our surgical approach allowed us to drain two cavities that are physiologically separated by the diaphragm, contrast with the bibliography that reports two separate drains.

In conclusion, timely treatment, extensive antibiotic coverage, and surgical cleaning contributed to the satisfactory resolution and clinical improvement of the patient.

The clinical relevance of the case focuses on timely management of a complication secondary to an untreated subphrenic abscess. Due to the few reported cases, there isn’t a defined percentage of purulent pericarditis secondary to abdominal abscesses. Reporting more cases could lead to a deeper study of this pathology with this case and others.

Ethical disclosuresThe authors declare that a written informed consent was obtained for the publication of the case.

Source of fundingNo funding was received for this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.