Ministernotomy (MS) is a minimally invasive approach for aortic valve replacement which aims to reduce operative trauma and enhance recovery. However, the impact of MS on perioperative mortality and long-term survival remains debated. Thus, the propose of our study was to compare the outcomes of AVR performed through FS versus MS, to determine which approach offers better results in terms of mortality, recovery, safety, and long-term survival.

MethodsThe present study is a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent isolated AVR from 2014 (year in which the first AVR trough MS was performed) to 2023 at our institution. Statistical adjustment for treatment intervention (MS) was performed by estimating the propensity score with inverse probability weighting.

Results30-Day mortality occurred in 0.39% in the MS group and 1.63% in the FS group (adjusted RD: −0.014; 95% CI: −0.029, 0.001; p=0.080). Survival analysis at 3-year follow-up revealed no significant differences in the HR between groups (92.5% vs 90.4%; HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.40, 1.54; p=0.479). We observed a significant risk reduction in the MS group for sternal wound infection (adjusted RD: −0.021; 95% CI: −0.039, 0.003; p=0.024), Intubation time (adjusted RD: −8.80; 95% CI: −15.04, −2.56; p=0.024), postoperative bleeding (adjusted RD: −0.037; 95% CI: −0.074, −0.001; p=0.049) and stage 4 AKI (adjusted RD: −0.016; 95% CI: −0.031, −0.001; p=0.032).

ConclusionIn a retrospective, single-center study, AVR through MS presented no significant differences compared to FS regarding 30-day mortality and 3-year survival. MS was associated with a significantly lower risk for postoperative DSWI, wound dehiscence, bleeding requiring reintervention, AKI requiring renal replacement therapy and a significantly shorter intubation time.

La miniesternotomía (MS) es un abordaje mínimamente invasivo para la cirugía de sustitución valvular aórtica (AVR) que busca reducir el trauma operatorio y optimizar la recuperación. No obstante, el impacto de la MS en la mortalidad perioperatoria y la supervivencia continúa siendo motivo de debate. Por lo tanto, el objetivo del estudio fue comparar los resultados del AVR mediante esternotomía completa (FS) frente a MS, para terminar que abordaje ofrece mejores resultados en términos de mortalidad, recuperación, seguridad y supervivencia.

MétodosEl presente estudio es un análisis retrospectivo de pacientes intervenidos de AVR aislada entre 2014 (año en que se realizó la primer AVR mediante MS) y 2023 en nuestra institución. Se realizó un ajuste estadístico mediante la estimación de la puntuación de propensión con ponderación de la probabilidad inversa de tratamiento.

ResultadosLa mortalidad a 30 días fue del 0.39% en el grupo de MS y del 1.63% en el grupo de FS (Diferencia de riesgo ajustada: -0.014; 95% CI: -0.029, 0.001; p=0.080) El análisis de supervivencia a los 3 años de seguimiento no mostró diferencias significativas en la razón de riesgo entre los grupos (92.5% vs 90.4%; HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.40, 1.54; p=0.479). Se observó una disminución significativa del riesgo en el grupo de MS para mediastinitis (RD: -0.021; 95% CI: -0.039, 0.003; p=0.024), tiempo de intubación (RD: -8.80; 95% CI: -15.04, -2.56; p=0.024), sangrado postquirúrgico (RD: -0.037; 95% CI: -0.074, -0.001; p=0.049) y fracaso renal estadio 4 (RD: -0.016; 95% CI: -0.031, -0.001; p=0.032).

ConclusiónEn el presente estudio retrospectivo y unicéntrico, no se identificaron diferencias significativas respecto a mortalidad perioperatoria y supervivencia a 3 años entre AVR mediante FS y MS. La AVR mediante MS se asoció con un riesgo significativamente menor de mediastinitis, sangrado postquirúrgico, fracaso renal agudo con requerimiento de terapia de reemplazo renal y un tiempo de intubación significativamente más corto.

Aortic valve replacement (AVR) is the gold standard for the treatment of severe aortic valve pathologies (stenosis and regurgitation). While traditionally performed using a full sternotomy (FS) approach, it involves considerable trauma and potentially longer recovery times. Ministernotomy (MS) is a minimally invasive approach which aims to reduce operative trauma, with evidence suggesting benefits such as shorter hospital stays, reduced ICU times, and lower rates of wound complications.1–4 Despite these advantages, the impact of MS on perioperative mortality and long-term survival remains debated. Thus, the propose of our study was to compare the outcomes of AVR performed through FS versus MS, to determine which approach offers better results in terms of mortality, recovery, safety, and long-term survival.

MethodsStudy designThe present study is a retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent isolated AVR from 2014 (year in which the first AVR trough MS was performed) to 2023 at our institution. Exclusion criteria included any concomitant procedure, emergency surgery, critical preoperative state as defined in the EuroScore II, previous cardiac surgery, chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis, any significant coronary artery stenosis and acute infective endocarditis.

DefinitionsPostoperative myocardial infarction was defined as an increase in Troponin T or CK-MB above 5 times the percentile of the reference range during the first 72h after the procedure, associated with electrocardiographic or echocardiographic changes suggesting ischemia.

Postoperative stroke was defined as a focal or global neurological deficit lasting more than 24h or <24h if available neuroimaging documented new hemorrhage or infarction.

Preoperative risk was estimated using the EuroScore II (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation).5

Surgical techniqueUnder general anesthesia, a partial upper J-ministernotomy was performed through a 6–8cm skin incision extending from the head of the second rib to the third or fourth intercostal space carefully avoiding injury to the right internal thoracic artery. For enhanced exposure, thymic fat tissue was removed, and pericardial suspension stitches were placed under the retractor. Cardiopulmonary bypass was established by direct aortic cannulation into the ascending aorta or proximal aortic arch and venous cannulation via the right atrium appendage. Myocardial preservation with cardioplegic solution was administered non-selectively into the aortic root in cases of aortic stenosis or selectively into the coronary ostia for significant aortic insufficiency. The surgical technique for aortic valve replacement was similar for MS and FS and the prosthesis selection was decided following current guideline recommendations and patient preferences.

Data collectionInformation regarding previous medical history, details of the surgical procedure and postoperative events were recorded in a prospective database. The information regarding survival was obtained after matching each patient's individual data with the National Death Index Registry (INDEF) from the Spanish Ministry of Health.

EndpointsThe primary endpoint was to compare the 30-day mortality and the 3-year survival between patients who underwent isolated AVR through a FS or MS approach. Secondary endpoints included postoperative deep wound sternal infection, wound dehiscence, atrial fibrillation, postoperative intubation time (hours), postoperative ICU stay (days) and postoperative hospital stay (days). Safety endpoints included postoperative stroke, myocardial infarction, bleeding requiring reintervention, acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (Stage 4) and prolonged intubation (>24h).

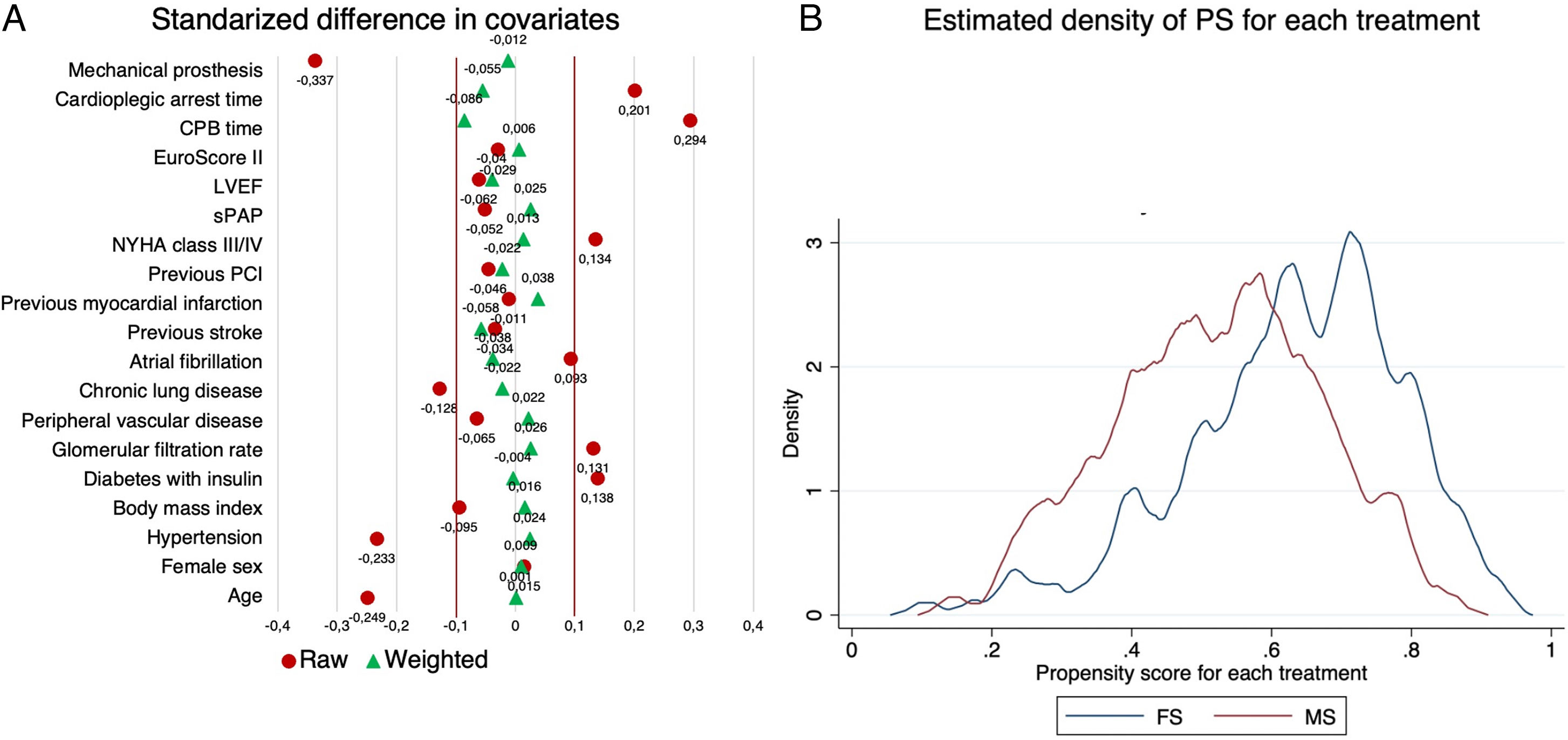

Data analysisAll perioperative variables were tested for normality. Quantitative variables were expressed as median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Between-group comparisons were performed using the t-test for quantitative variables and the X2 test for categorical variables. Statistical adjustment for treatment intervention (MS) was performed by estimating the propensity score with inverse probability weighting (IPW), where treated patients had a weight of 1 over the propensity score (1/PS) and untreated ones had a weight of 1 over 1 minus the propensity score (1/(1−PS)). The adequacy of adjustment was evaluated by estimating the mean standardized difference for each variable, with an adequate value<0.1; additionally, the overlap assumption was visually assessed by plotting the estimated densities of the PS for each treatment. The risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was estimated as treatment effect for 30-day mortality and postoperative endpoints and the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI was estimated as treatment effect for survival. In addition to the HR, the restricted mean survival time (RMST), which is defined as the area under the survival curve up to a specific time point and can be interpreted as the average survival time during a defined period of time, was estimated at 1, 2 and 3 years, along with between-group comparisons for the absolute RMST difference.6 All tests were two tailed and P-values<0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 17.

EthicsThis study follows the recommendations of the Helsinki Declaration for medical research. Given the retrospective nature of this study, patient consent was not required.

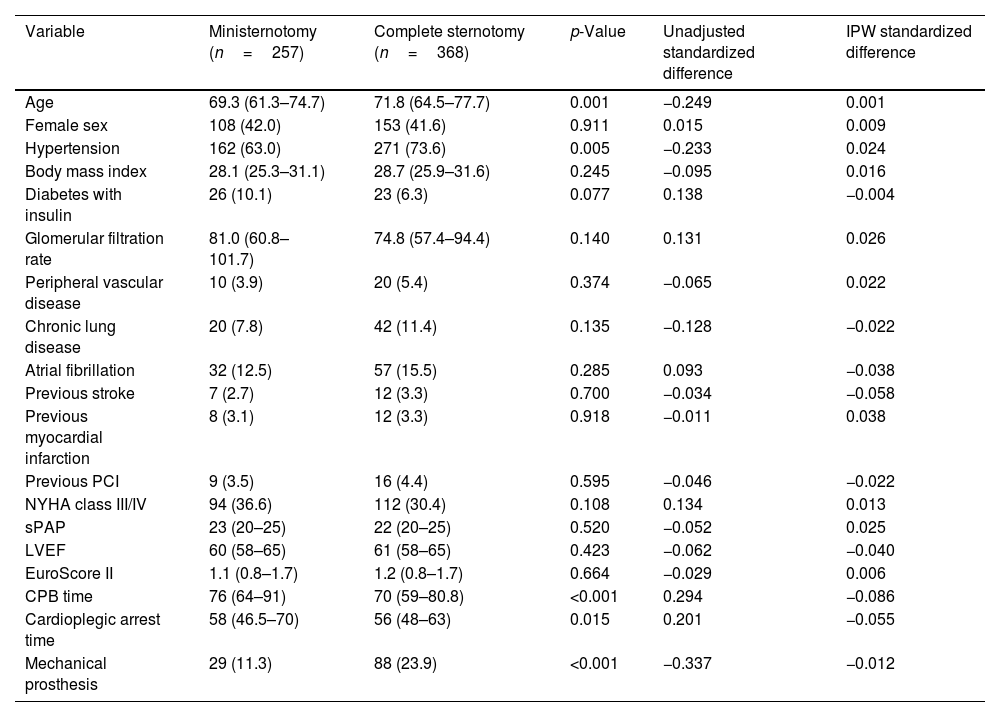

Results625 patients were included, 257 patients underwent AVR through a MS and 368 patients through a FS. Patients in the FS group were significantly older (FS 71.8 years; IQR: 64.5, 77.7; MS 69.3 years; IQR: 61.3, 74.7; p=0.001) and had a higher prevalence of hypertension (p=0.005). Other comorbidities such as peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, glomerular filtration rate, previous stroke and myocardial infarction showed no significant differences between groups. The median EuroScore II was similar between groups (MS 1.1%; IQR: 0.8, 1.7; FS 1.2%; IQR: 0.8, 1.7; p=0.664). Median cardiopulmonary bypass and cardioplegic arrest times were significantly shorter in the FS group (p<0.001). Mechanical prostheses were most commonly implanted in FS approach. Preoperative and procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 1. After IPW adjustment, preoperative variables were well balanced between the two groups with a standardized difference<0.1 for each covariate and the overlap assumption for the estimated density of the PS for each treatment was not violated (Fig. 1).

Preoperative and operative characteristics. Values are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

| Variable | Ministernotomy (n=257) | Complete sternotomy (n=368) | p-Value | Unadjusted standardized difference | IPW standardized difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.3 (61.3–74.7) | 71.8 (64.5–77.7) | 0.001 | −0.249 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 108 (42.0) | 153 (41.6) | 0.911 | 0.015 | 0.009 |

| Hypertension | 162 (63.0) | 271 (73.6) | 0.005 | −0.233 | 0.024 |

| Body mass index | 28.1 (25.3–31.1) | 28.7 (25.9–31.6) | 0.245 | −0.095 | 0.016 |

| Diabetes with insulin | 26 (10.1) | 23 (6.3) | 0.077 | 0.138 | −0.004 |

| Glomerular filtration rate | 81.0 (60.8–101.7) | 74.8 (57.4–94.4) | 0.140 | 0.131 | 0.026 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10 (3.9) | 20 (5.4) | 0.374 | −0.065 | 0.022 |

| Chronic lung disease | 20 (7.8) | 42 (11.4) | 0.135 | −0.128 | −0.022 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 32 (12.5) | 57 (15.5) | 0.285 | 0.093 | −0.038 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (2.7) | 12 (3.3) | 0.700 | −0.034 | −0.058 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 8 (3.1) | 12 (3.3) | 0.918 | −0.011 | 0.038 |

| Previous PCI | 9 (3.5) | 16 (4.4) | 0.595 | −0.046 | −0.022 |

| NYHA class III/IV | 94 (36.6) | 112 (30.4) | 0.108 | 0.134 | 0.013 |

| sPAP | 23 (20–25) | 22 (20–25) | 0.520 | −0.052 | 0.025 |

| LVEF | 60 (58–65) | 61 (58–65) | 0.423 | −0.062 | −0.040 |

| EuroScore II | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.664 | −0.029 | 0.006 |

| CPB time | 76 (64–91) | 70 (59–80.8) | <0.001 | 0.294 | −0.086 |

| Cardioplegic arrest time | 58 (46.5–70) | 56 (48–63) | 0.015 | 0.201 | −0.055 |

| Mechanical prosthesis | 29 (11.3) | 88 (23.9) | <0.001 | −0.337 | −0.012 |

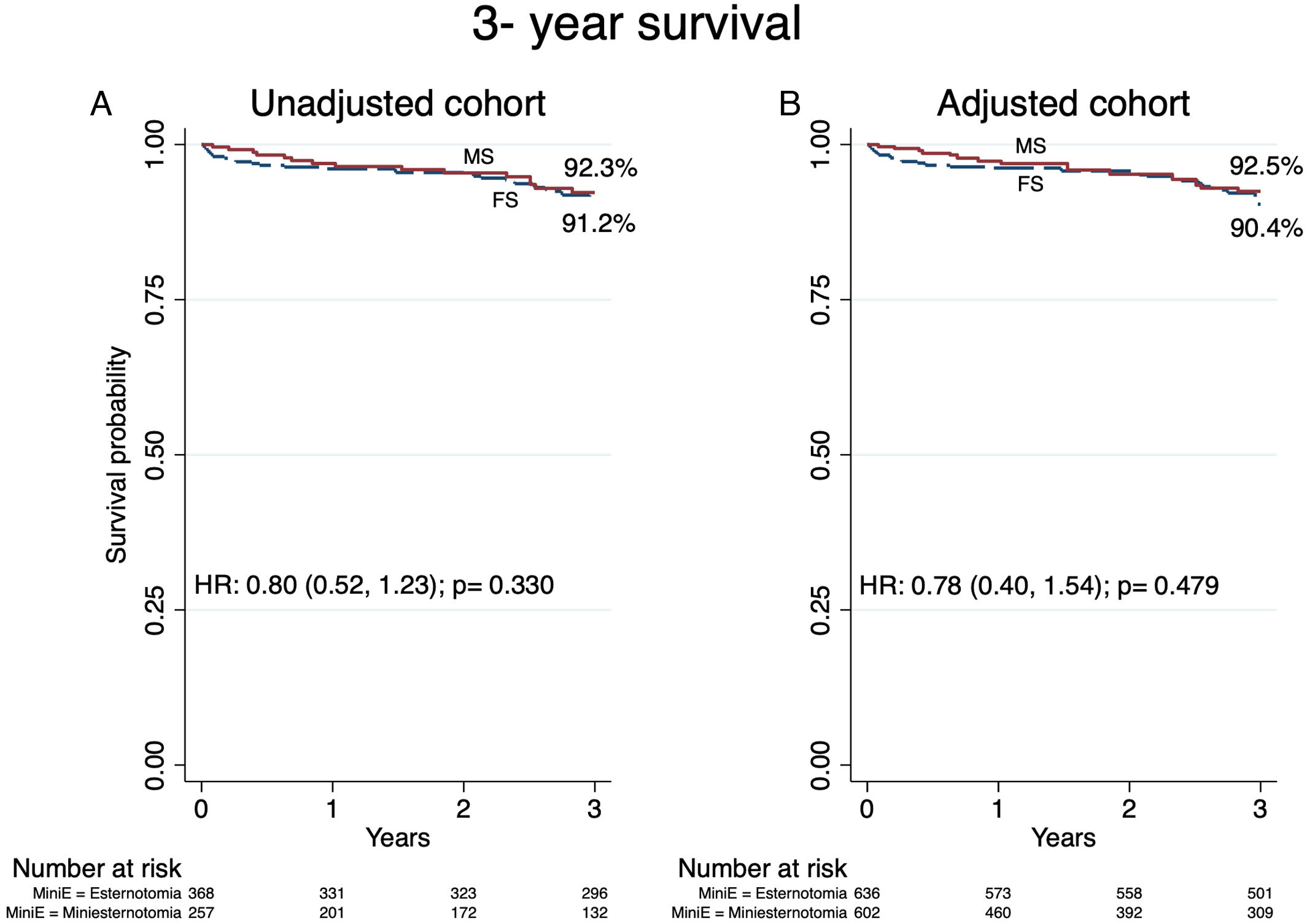

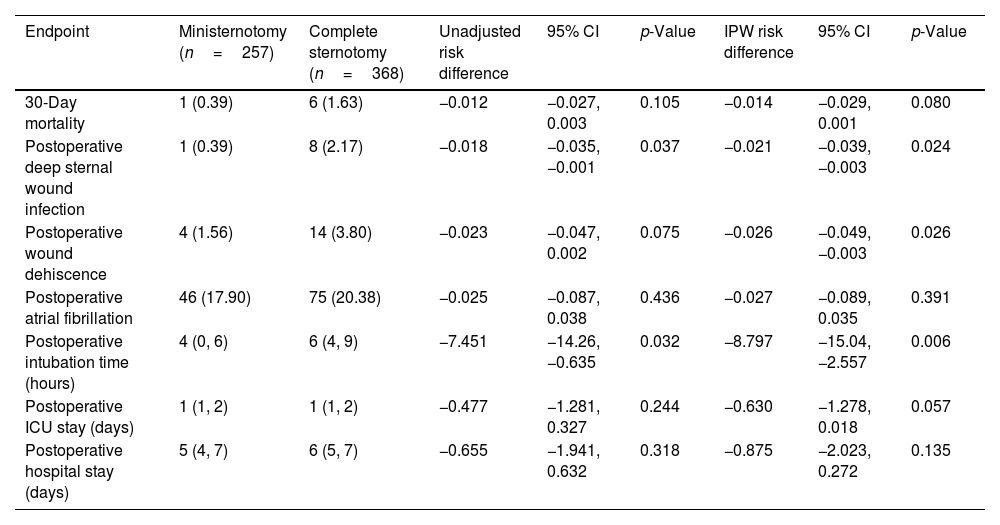

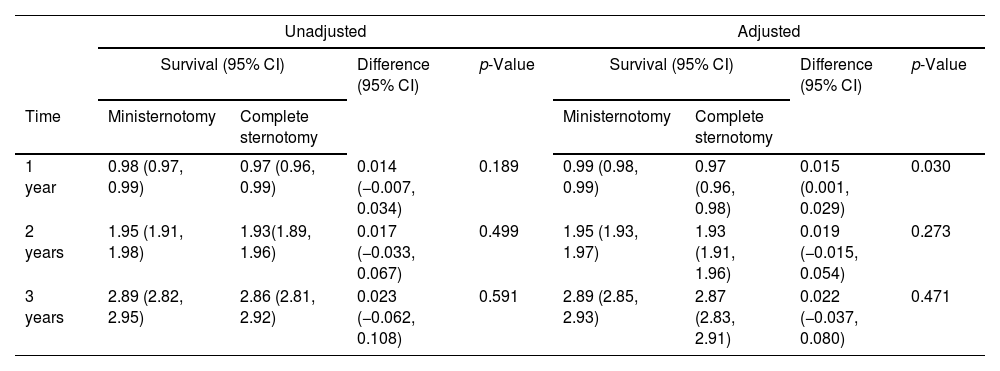

30-Day mortality occurred in 0.39% in the MS group and 1.63% in the FS group (unadjusted RD: −0.012; 95% CI: −0.027, 0.003; p=0.105; adjusted RD: −0.014; 95% CI: −0.029, 0.001; p=0.080) (Table 2). Median follow up for FS was 6.2 years (IQR: 4.2, 8.0) and 3.5 (IQR: 1.3–5.9) for MS. Survival analysis at 3-year follow-up revealed no significant differences in the HR between groups in the adjusted (92.5% vs 90.4%; HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.40, 1.54; p=0.479) and unadjusted (92.3% vs 91.2%; HR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.52, 1.23; p=0.330) cohort (Fig. 2). The RMST in the adjusted cohort was significantly higher at 1 year in the MS group (RMST difference: 0.015 years; 95%CI: 0.001, 0.029; p=0.030), without significant differences at 2 and 3 years and without significant differences in the unadjusted cohort (Table 3).

30-Day mortality and secondary endpoints. Values are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

| Endpoint | Ministernotomy (n=257) | Complete sternotomy (n=368) | Unadjusted risk difference | 95% CI | p-Value | IPW risk difference | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day mortality | 1 (0.39) | 6 (1.63) | −0.012 | −0.027, 0.003 | 0.105 | −0.014 | −0.029, 0.001 | 0.080 |

| Postoperative deep sternal wound infection | 1 (0.39) | 8 (2.17) | −0.018 | −0.035, −0.001 | 0.037 | −0.021 | −0.039, −0.003 | 0.024 |

| Postoperative wound dehiscence | 4 (1.56) | 14 (3.80) | −0.023 | −0.047, 0.002 | 0.075 | −0.026 | −0.049, −0.003 | 0.026 |

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation | 46 (17.90) | 75 (20.38) | −0.025 | −0.087, 0.038 | 0.436 | −0.027 | −0.089, 0.035 | 0.391 |

| Postoperative intubation time (hours) | 4 (0, 6) | 6 (4, 9) | −7.451 | −14.26, −0.635 | 0.032 | −8.797 | −15.04, −2.557 | 0.006 |

| Postoperative ICU stay (days) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | −0.477 | −1.281, 0.327 | 0.244 | −0.630 | −1.278, 0.018 | 0.057 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 5 (4, 7) | 6 (5, 7) | −0.655 | −1.941, 0.632 | 0.318 | −0.875 | −2.023, 0.272 | 0.135 |

Survival at 3-year follow-up in unadjusted and adjusted cohorts. MS: ministernotomy; FS: full sternotomy; HR: hazard ratio. Central figure. Study design, primary and secondary outcomes. AVR: aortic valve replacement; MS: ministernotomy; FS: full sternotomy; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CAD: coronary artery disease; IE: infective endocardtis; MI: myocardial infarction; DSWI: deep sternal wound infection.

Restricted mean survival time for the unadjusted and adjusted cohorts. Values are presented as mean (95% confidence interval).

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | Survival (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Time | Ministernotomy | Complete sternotomy | Ministernotomy | Complete sternotomy | ||||

| 1 year | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.014 (−0.007, 0.034) | 0.189 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.015 (0.001, 0.029) | 0.030 |

| 2 years | 1.95 (1.91, 1.98) | 1.93(1.89, 1.96) | 0.017 (−0.033, 0.067) | 0.499 | 1.95 (1.93, 1.97) | 1.93 (1.91, 1.96) | 0.019 (−0.015, 0.054) | 0.273 |

| 3 years | 2.89 (2.82, 2.95) | 2.86 (2.81, 2.92) | 0.023 (−0.062, 0.108) | 0.591 | 2.89 (2.85, 2.93) | 2.87 (2.83, 2.91) | 0.022 (−0.037, 0.080) | 0.471 |

Secondary endpoints are summarized in Table 2. Postoperative DSWI occurred in 0.39% in the MS group and 2.17% in the FS group, with a RD significantly lower both cohorts (unadjusted RD: −0.018; 95% CI: −0.035, 0.001; p=0.037; adjusted RD: −0.021; 95% CI: −0.039, 0.003; p=0.024). In addition, the MS group also presented a significantly lower RD for wound dehiscence (unadjusted RD: −0.018; 95% CI: −0.035, 0.001; p=0.037; adjusted RD: −0.021; 95% CI: −0.039, 0.003; p=0.024) and intubation time (unadjusted RD: −0.018; 95% CI: −0.035, 0.001; p=0.037; adjusted RD: −0.021; 95% CI: −0.039, 0.003; p=0.024).

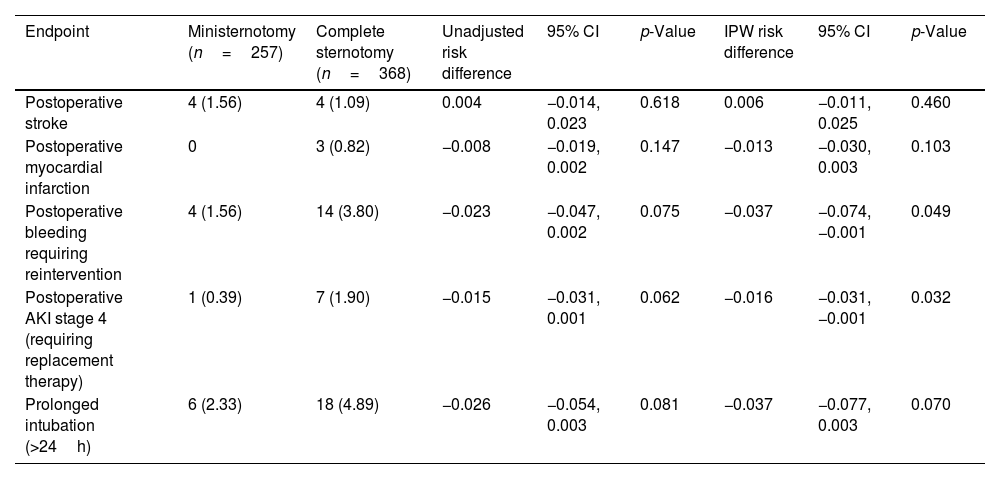

Regarding safety endpoints, we found no significant differences for postoperative stroke, MI and prolonged intubation. However, we did observe a significant RD reduction in the MS group for postoperative bleeding (adjusted RD: −0.037; 95% CI: −0.074, −0.001; p=0.049) and stage 4 AKI (adjusted RD: −0.016; 95% CI: −0.031, −0.001; p=0.032) in the adjusted cohort (Table 4).

Safety endpoints. Values are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

| Endpoint | Ministernotomy (n=257) | Complete sternotomy (n=368) | Unadjusted risk difference | 95% CI | p-Value | IPW risk difference | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative stroke | 4 (1.56) | 4 (1.09) | 0.004 | −0.014, 0.023 | 0.618 | 0.006 | −0.011, 0.025 | 0.460 |

| Postoperative myocardial infarction | 0 | 3 (0.82) | −0.008 | −0.019, 0.002 | 0.147 | −0.013 | −0.030, 0.003 | 0.103 |

| Postoperative bleeding requiring reintervention | 4 (1.56) | 14 (3.80) | −0.023 | −0.047, 0.002 | 0.075 | −0.037 | −0.074, −0.001 | 0.049 |

| Postoperative AKI stage 4 (requiring replacement therapy) | 1 (0.39) | 7 (1.90) | −0.015 | −0.031, 0.001 | 0.062 | −0.016 | −0.031, −0.001 | 0.032 |

| Prolonged intubation (>24h) | 6 (2.33) | 18 (4.89) | −0.026 | −0.054, 0.003 | 0.081 | −0.037 | −0.077, 0.003 | 0.070 |

Over the past decades, advancements in surgical techniques and postoperative care have greatly enhanced outcomes in patient undergoing AVR. However, there is no recommendation regarding surgical approach in current guidelines.3,7

The impact of MS in perioperative mortality and survival remains debated. Despite 30-day mortality was low in both MS and FS, we observed a 1.4% reduction in the risk for 30-day mortality after covariate adjustment. Nonetheless, these differences were not statically significant most likely due to sample size. Larger multicenter registries have in fact reported a significant benefit in 30 day mortality and in the largest metanalysis to date, a significant benefit in mortality was reported for minimally invasive AVR.2,8,9 We believe the causes are multifactorial but related with reduced operative trauma and improved recovery with less perioperative complications. Regarding survival, both approaches were associated with favorable results without significant differences in the HR at 3-year follow up. Potential confounders such as age, the use of mechanical or bioprosthetic valves and other comorbidities were well balanced in the adjusted cohort. A significant benefit for MS was observed in the RMST difference only at 1-year in the adjusted cohort, probably related to the perioperative benefit of the MS approach. Evidence is scarce regarding mid-term results comparing both approaches, with survival for FS ranging from 75% to 84% and 80% to 91% for MS.3,10,11

Beyond mortality and survival, MS demonstrated advantages in several secondary and safety endpoints. The incidence of postoperative bleeding requiring reintervention, DWSI and wound dehiscence were lower in the MS group, likely due to the less invasive nature of the procedure, reduced wound exposure and smaller incision size. The rates of bleeding requiring reintervention for MS in previous studies range from 2.5% to 6%, while in our study only 1.56% presented this complication.1,4,10 The incidence of DSWI in the MS group was 0.39% and after adjustment, we observed a reduction in 2.1% for the risk of DSWI in the MS group; an important observation since DSWI is associated with an increase in hospital stay and higher mortality.12 Additionally, postoperative intubation time was significantly shorter in the MS group, indicating a faster recovery and reduced need for extended respiratory support.2,4 The latter has also been associated with a lower risk for postoperative wound and respiratory tract infections.13,14 Finally, a significant reduction in the risk for postoperative stage 4 AKI (1.6%) in the adjusted cohort was also observed. Postoperative AKI requiring renal replacement therapy affects between 1% and 5% of patients and is strongly associated with increased perioperative mortality, DSWI, endocarditis and reduced survival at follow up.15,16 The implications of these findings in daily practice are substantial, and if we consider the MS approach as a part of the enhanced recovery process after AVR, we believe there is a significant margin for further improvement in clinical endpoints as well as in resource utilization (Central figure).

Contemporary trials comparing AVR with transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in low-risk patients report 30-day mortality rates between 0.9% and 1.5% for AVR and 0.4% and 0.6% for TAVI.17–20 In addition, midterm survival for AVR ranged from 87% to 91% and 91% to 90% for TAVI.21,22 In our study, we reported a 30-day mortality rate of 0.39% and a 92.3% survival at 3-year follow up in the MS cohort. The use of MS in those trials was marginal, ranging between 24% and 38%. Given our findings, in addition to others reported previously,2,23 we support the idea that future trials comparing both treatments should consider minimally invasive AVR as the standard of care for the surgical arm.

Further large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials are necessary to solidify the position of MS as the preferred surgical approach for AVR, but the present study adds evidence to the argument for its broader adoption.

LimitationsDespite the strengths of our study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this study was retrospective in nature, which inherently carries the risk of selection bias and confounding factors. Although we used IPW to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics, unmeasured confounders could still influence the outcomes. Second, the data was collected over a 9-year period, during which surgical techniques, postoperative care, and patient management practices likely evolved. These changes could impact the comparability of outcomes across the study period and some temporal biases may remain. Finally, the study was conducted at a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of our results to other settings with different patient populations, surgical expertise, and healthcare infrastructures.

ConclusionIn a retrospective, single-center study, AVR through MS presented no significant differences compared to FS regarding 30-day mortality and 3-year survival. MS was associated with a significantly lower risk for postoperative DSWI, wound dehiscence, bleeding requiring reintervention, AKI requiring renal replacement therapy and a significantly shorter intubation time.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.