Successful surgical mitral valve repair in native mitral valve infective endocarditis (IE) remains challenging. We report on the clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients with native mitral IE who underwent successful surgical mitral valve repair.

MethodsConsecutive patients with native mitral valve IE and indication for urgent or elective surgical treatment between 2000 and 2024 were evaluated and followed-up for the occurrence of death, recurrence of IE, significant valvular dysfunction, need for re-intervention, cerebrovascular events (stroke/transient ischaemic accident) or major bleedings.

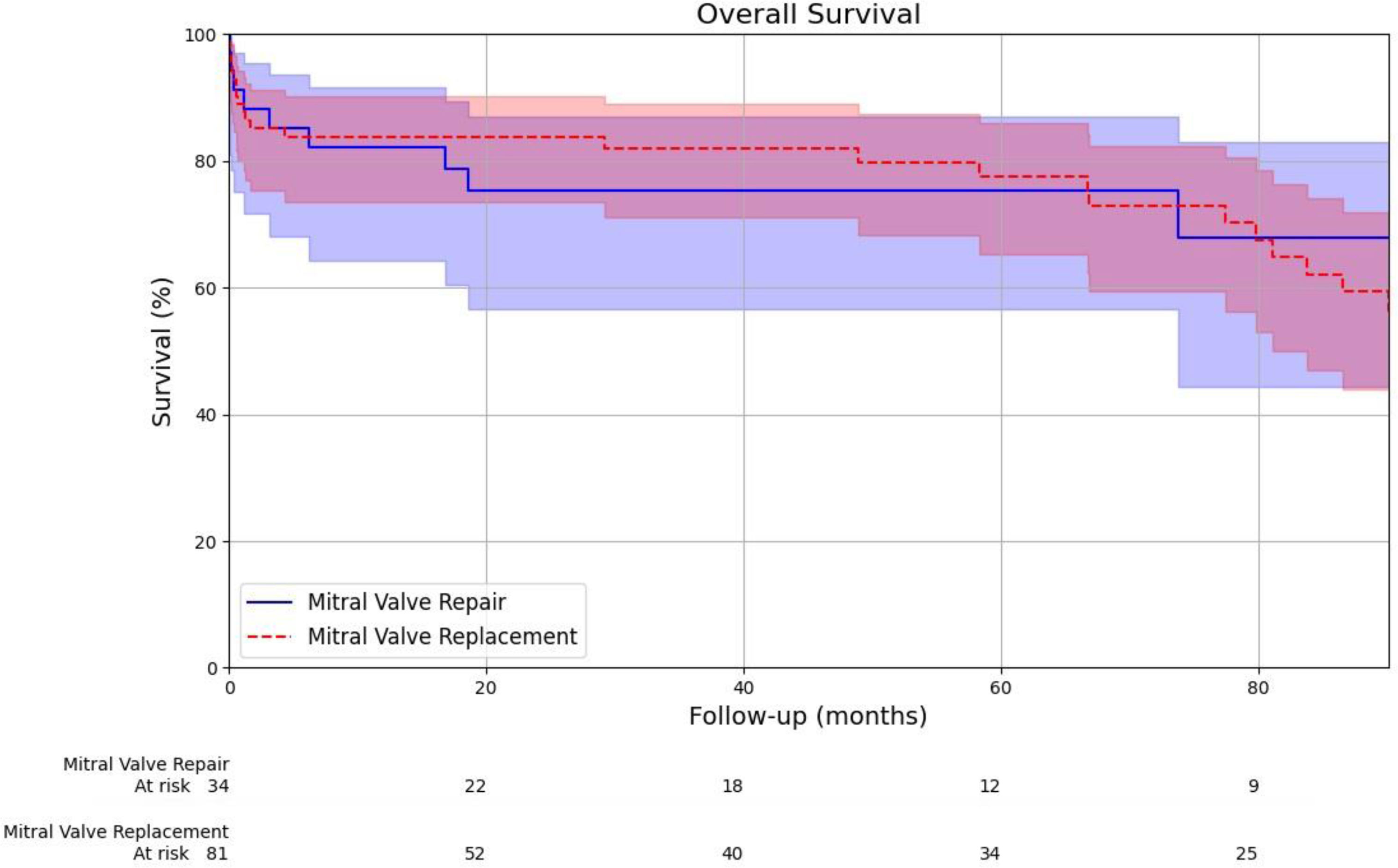

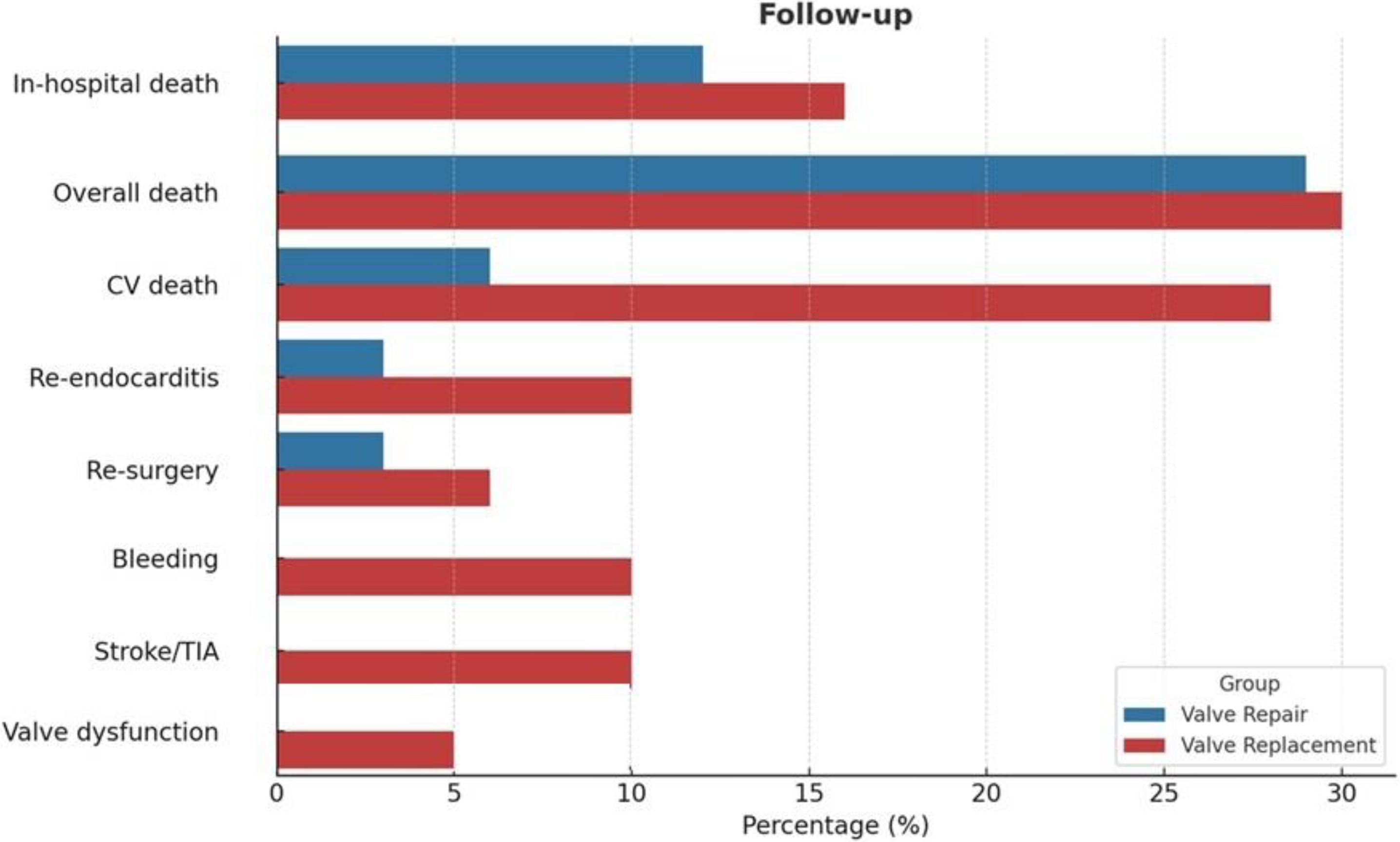

ResultsOf 116 patients (60±14 years, 58% male), 82 underwent surgical valve replacement (70%) and 34 (30%) valve repair. Both groups were comparable but the frequency of hypertension and atrial fibrillation was higher in the replacement group. Uncontrolled infection was more frequent in the replacement group (44% vs. 9%, p<0.01). The replacement group showed larger destruction of the valve as compared to their counterpart. During a median follow-up of 5 years, the survival rates were similar in both groups (75% vs 77% in the mitral valve repair vs replacement, hazard ratio 1.03, p=0.928). Recurrence of IE, major bleedings and neurological complications were more frequent and significant valve dysfunction was reported only in the replacement group (5%, p=0.18).

ConclusionMitral valve repair for native mitral valve IE is safe and feasible when there is no significant structural damage. At 5-year follow-up, surgical repair is associated with less frequency of recurrent IE, neurological complications and valve dysfunction as compared to surgical replacement.

La reparación quirúrgica exitosa de la válvula mitral en la endocarditis infecciosa (EI) de la válvula mitral nativa sigue siendo un reto. Presentamos las características clínicas y ecocardiográficas de pacientes con EI de la válvula mitral nativa sometidos a una reparación quirúrgica exitosa de la válvula mitral.

MétodosSe evaluó y realizó seguimiento de pacientes consecutivos con EI de la válvula mitral nativa e indicación de tratamiento quirúrgico urgente o electivo entre 2000 y 2024. Se recogieron datos de mortalidad global, recurrencia de la EI, disfunción valvular significativa, necesidad de reintervención, eventos cerebrovasculares (ictus/accidente isquémico transitorio) o hemorragias mayores.

ResultadosDe 116 pacientes (60±14 años, 58% varones), 82 se sometieron a reemplazo valvular quirúrgico (70%) y 34 (30%) a reparación valvular. Ambos grupos fueron comparables, pero la frecuencia de hipertensión y fibrilación auricular fue mayor en el grupo de reemplazo quirúrgico. La infección no controlada fue más frecuente en el grupo de reemplazo quirúrgico (44% vs. 9%, p<0,01). El grupo de reemplazo quirúrgico mostró una mayor destrucción valvular en comparación con su contraparte. Durante una mediana de seguimiento de 5 años, las tasas de supervivencia fueron similares en ambos grupos (75% vs. 77% en la reparación vs. el reemplazo valvular mitral, hazard ratio 1,03, p=0,928). La recurrencia de EI, las hemorragias mayores y las complicaciones neurológicas fueron más frecuentes, y solo se reportó disfunción valvular significativa en el grupo de reemplazo quirúrgico (5%, p=0,18).

ConclusiónLa reparación valvular mitral para la EI de válvula mitral nativa es segura y factible cuando no existe daño estructural significativo. A los 5 años de seguimiento, la reparación quirúrgica se asocia con una menor frecuencia de EI recurrente, complicaciones neurológicas y disfunción valvular en comparación con el reemplazo quirúrgico.

According to international guidelines, surgical treatment of infective endocarditis (IE) is indicated in uncontrolled infection despite proper antibiotic treatment, heart failure and in case of embolisation or high risk of embolisation.1 The main aim of surgery is to remove infected structures, to avoid and limit, when possible, the use of prosthetic material, trying to preserve valvular anatomy and its haemodynamic function. A delayed surgery often leads to the progression of the disease, favouring tissue disintegration and involving the structures outside the valve annulus,2 requiring a more complex surgical approach and often poor outcomes. Surgical mitral valve repair is the preferred treatment for primary mitral regurgitation, but its role in the context of native mitral valve IE is not well established. Different studies and metanalysis reported excellent outcomes of surgical mitral valve repair, supporting its safety and feasibility in this complex clinical context.2–6 The present study aims at analysing the clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients with native mitral valve IE who underwent surgical mitral valve repair and at reporting the intermediate outcomes of surgical mitral valve repair in comparison with mitral valve replacement.

MethodsStudy designThis is a retrospective observational study conducted at Hospital University Germans Trias i Pujol (Badalona, Spain). The study included patients diagnosed with mitral valve IE between January 2000 and September 2024, who received surgical treatment either with mitral valve repair or mitral valve replacement. Demographic and clinical data were obtained retrospectively from electronic medical records.

Study populationPatients diagnosed with native mitral valve IE who had an indication for surgical treatment were included in the study. The diagnosis of IE was based on contemporary modified Duke criteria.7,8 Demographic data included sex and age, and clinical data included cardiovascular risk factors, clinical symptoms and signs, laboratory and microbiological data. Echocardiographic data (transthoracic and transoesophageal) were analysed to characterise the valve lesions according to established definitions.1

Surgical techniqueAll cardiac surgeries were performed through a median sternotomy on full cardiopulmonary bypass between the 2 venae cava and the ascending aorta. Myocardial protection consisted of antegrade cold blood cardioplegia. Mitral valve exposure was achieved through a standard left atriotomy. Surgical planning was re-evaluated intraoperatively based on direct valve inspection.

For mitral valve repair and replacement, the basic surgical principle was complete resection of all infected valvular and subvalvular tissue. Valve reconstruction was performed according to Carpentier's techniques, if mitral valve repair was pursued, including leaflet resection, transposition of chordae, pericardial patching or direct suturing of the perforation. A prosthetic ring was consistently used. If needed, tricuspid valve annuloplasty was also performed as well as any other concomitant intervention such as coronary artery bypass grafting or aortic valve replacement. The surgical repair result was evaluated at the operating theatre with transoesophageal echocardiography.

Study endpointsThe postoperative course and the intermediate follow-up were assessed retrospectively, evaluating the occurrence of the primary endpoint of all cause death as well as other secondary endpoints such as the recurrence of IE or significant valvular dysfunction, any need for re-intervention and the occurrence of cerebrovascular events (stroke/transient ischaemic accident) or major bleedings.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are reported as mean±standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR) according to the distribution of the variable. The Student T-test was used for comparison of continuous variables, and the Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Time to all-cause mortality was analysed with the Kaplan–Meier method and comparison between groups was performed with a log-rank test. The hazard ratios (HR) with the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided.

EthicsThe study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (PI-25-085/27 May 2025) and due to its retrospective nature, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

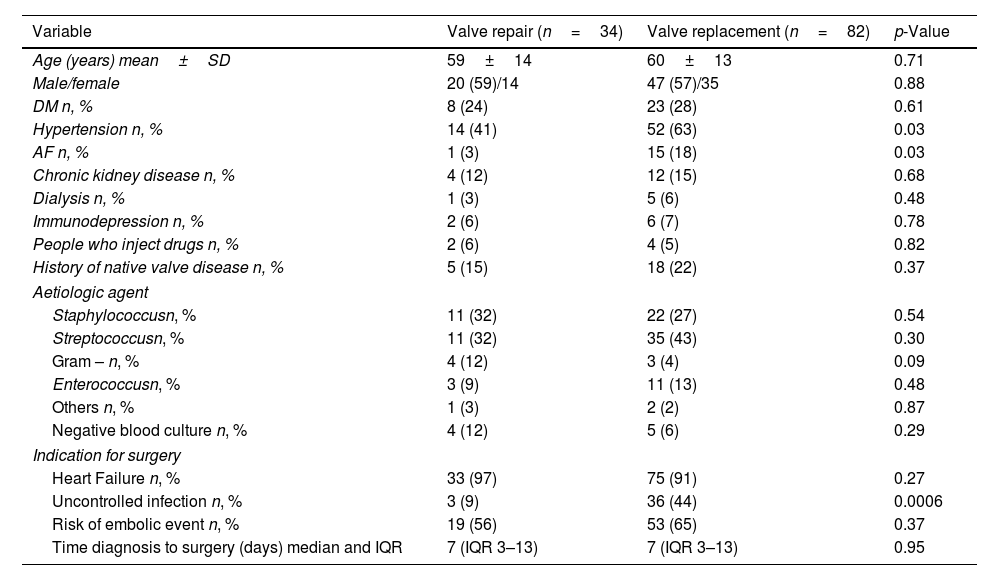

ResultsA total of 116 consecutive patients who were referred to the Cardiothoracic Surgery Department of the Hospital University Germans Trias i Pujol (Badalona, Spain) from January 2000 to September 2024 were evaluated. Out of 116 patients, 82 underwent surgical valve replacement (70%) and 34 valve repair (30%) according to surgical team decision. The mean age of patients was similar in both groups (59±14 years in the mitral valve repair group vs. 60±13 years in the mitral valve replacement, p=0.71) and the sex distribution was comparable (59% male in the mitral valve repair group vs. 57% male in the mitral valve replacement, p=0.88) (Table 1). In terms of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, both groups of patients were also comparable except for hypertension and atrial fibrillation that were significantly more common in the group that underwent surgical mitral valve replacement as compared to the group of surgical mitral valve repair (63% vs. 41%, respectively; p=0.03 and 18% vs. 3%, respectively; p=0.03). The frequency of clinical conditions that increase the risk of IE such as use of intravenous drugs or known native valvular heart disease (mitral myxomatous disease, prolapse or rheumatic heart disease) were comparable between groups.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Valve repair (n=34) | Valve replacement (n=82) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean±SD | 59±14 | 60±13 | 0.71 |

| Male/female | 20 (59)/14 | 47 (57)/35 | 0.88 |

| DM n, % | 8 (24) | 23 (28) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension n, % | 14 (41) | 52 (63) | 0.03 |

| AF n, % | 1 (3) | 15 (18) | 0.03 |

| Chronic kidney disease n, % | 4 (12) | 12 (15) | 0.68 |

| Dialysis n, % | 1 (3) | 5 (6) | 0.48 |

| Immunodepression n, % | 2 (6) | 6 (7) | 0.78 |

| People who inject drugs n, % | 2 (6) | 4 (5) | 0.82 |

| History of native valve disease n, % | 5 (15) | 18 (22) | 0.37 |

| Aetiologic agent | |||

| Staphylococcusn, % | 11 (32) | 22 (27) | 0.54 |

| Streptococcusn, % | 11 (32) | 35 (43) | 0.30 |

| Gram – n, % | 4 (12) | 3 (4) | 0.09 |

| Enterococcusn, % | 3 (9) | 11 (13) | 0.48 |

| Others n, % | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | 0.87 |

| Negative blood culture n, % | 4 (12) | 5 (6) | 0.29 |

| Indication for surgery | |||

| Heart Failure n, % | 33 (97) | 75 (91) | 0.27 |

| Uncontrolled infection n, % | 3 (9) | 36 (44) | 0.0006 |

| Risk of embolic event n, % | 19 (56) | 53 (65) | 0.37 |

| Time diagnosis to surgery (days) median and IQR | 7 (IQR 3–13) | 7 (IQR 3–13) | 0.95 |

Abbreviations: AF – atrial fibrillation; DM – diabetes mellitus; IQR – interquartile range; SD – standard deviation.

In terms of causative microorganisms, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species were the most common in both groups, with no statistically significant differences (Table 1). Negative blood cultures were reported in 12% of patients in the surgical mitral valve repair group and 6% in the surgical mitral valve replacement group. Heart failure was the most frequent indication for surgery in both groups (97% in the mitral valve repair group vs. 91% in the mitral valve replacement group, p=0.27). However, uncontrolled infection was significantly more frequent in the surgical mitral valve replacement group as compared to the surgical mitral valve repair group (44% vs. 9%, p<0.01).

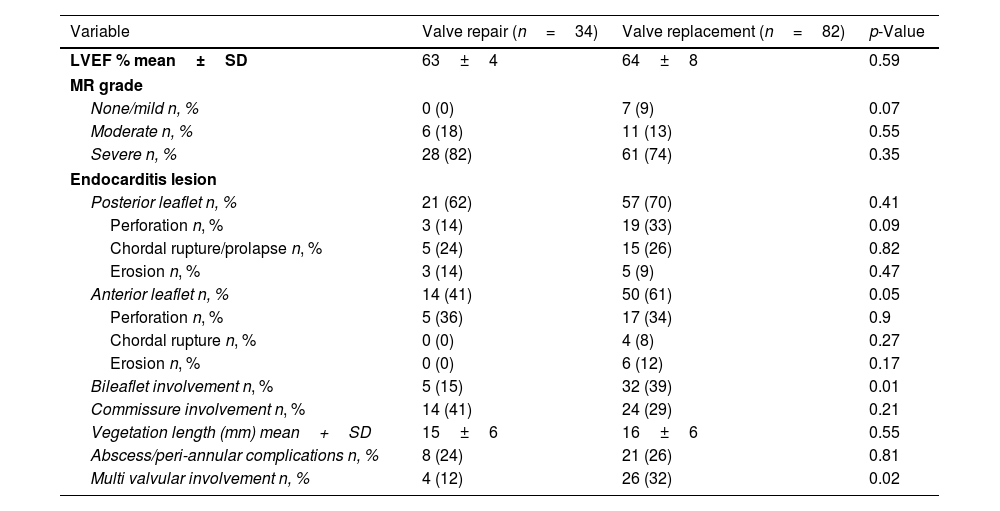

The median time from diagnosis to surgery was identical for both groups, with a median of 7 days (interquartile range 3–13). The echocardiographic data are presented in Table 2. The mean vegetation length was comparable between groups (15±6mm vs. 16±6mm, p=0.55). Lesions involving the posterior mitral leaflet were detected in 62% of patients in the surgical mitral valve repair group and 70% in the surgical mitral valve replacement group. However, the frequency of leaflet perforation was significantly higher in the surgical mitral valve replacement group as compared to the surgical mitral valve repair group (33% vs 14%, respectively; p=0.09). The anterior mitral leaflet was more frequently damaged in the surgical mitral valve replacement group as compared to the surgical mitral valve repair group (61% vs. 41%, p=0.05) and valve destruction with chordal rupture and erosion was more frequently observed in the surgical mitral valve replacement group. Bileaflet involvement was significantly more common in the surgical mitral valve replacement group as compared to the surgical mitral valve repair group (39% vs. 15%, p=0.01), while involvement of the mitral commissures, abscesses or peri-annular complications did not differ significantly between groups. Multi-valvular involvement was significantly more frequent in the surgical mitral valve replacement group as compared to the surgical mitral valve repair group (32% vs. 12%, p=0.02). Mitral regurgitation was the predominant valve dysfunction, with the majority of patients from both groups exhibiting severe grade of regurgitation without significant difference (82% in the surgical mitral valve repair group vs. 74% in the surgical mitral valve replacement group, p=0.35).

Baseline echocardiographic characteristics.

| Variable | Valve repair (n=34) | Valve replacement (n=82) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF % mean±SD | 63±4 | 64±8 | 0.59 |

| MR grade | |||

| None/mild n, % | 0 (0) | 7 (9) | 0.07 |

| Moderate n, % | 6 (18) | 11 (13) | 0.55 |

| Severe n, % | 28 (82) | 61 (74) | 0.35 |

| Endocarditis lesion | |||

| Posterior leaflet n, % | 21 (62) | 57 (70) | 0.41 |

| Perforation n, % | 3 (14) | 19 (33) | 0.09 |

| Chordal rupture/prolapse n, % | 5 (24) | 15 (26) | 0.82 |

| Erosion n, % | 3 (14) | 5 (9) | 0.47 |

| Anterior leaflet n, % | 14 (41) | 50 (61) | 0.05 |

| Perforation n, % | 5 (36) | 17 (34) | 0.9 |

| Chordal rupture n, % | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | 0.27 |

| Erosion n, % | 0 (0) | 6 (12) | 0.17 |

| Bileaflet involvement n, % | 5 (15) | 32 (39) | 0.01 |

| Commissure involvement n, % | 14 (41) | 24 (29) | 0.21 |

| Vegetation length (mm) mean+SD | 15±6 | 16±6 | 0.55 |

| Abscess/peri-annular complications n, % | 8 (24) | 21 (26) | 0.81 |

| Multi valvular involvement n, % | 4 (12) | 26 (32) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction; MR – mitral regurgitation; SD – standard deviation.

In the group receiving surgical mitral valve repair, 7 patients (21%) received concomitant procedures including 1 triple coronary artery bypass graft, aortic valve replacement in 3 patients (2 bioprostheses, 1 mechanical valve) and tricuspid valve annuloplasty was performed in 4 patients. Among the patients that received surgical mitral valve replacement, 49 received a mechanical prosthesis and 33 a bioprosthesis. Associated procedures included 1 case of double coronary artery bypass graft, 19 aortic valve replacements, of which one required reconstruction of the intervalvular fibrous body with an autologous pericardial patch, and 7 cases of tricuspid valve repair.

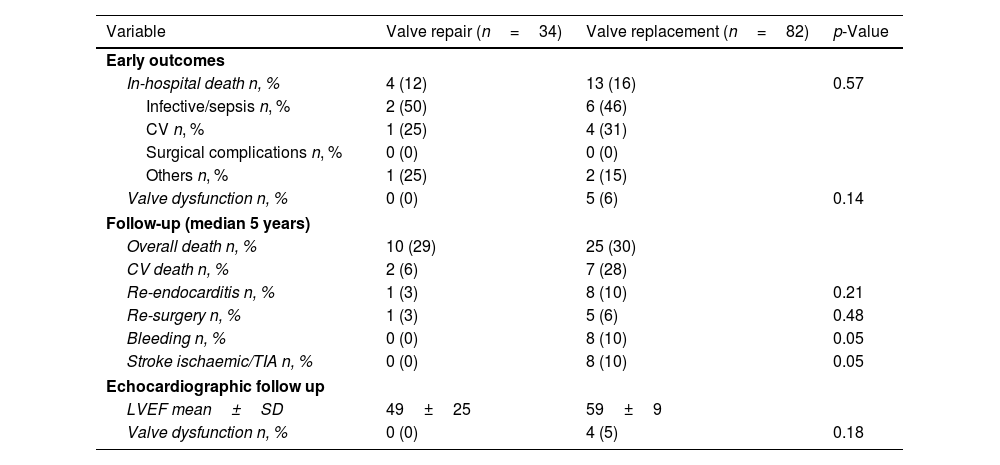

Study endpointsDuring the in-hospital postoperative course, 4 deaths (12%) were recorded in the surgical mitral valve repair group, whereas 13 in-hospital deaths (16%) were observed in surgical mitral valve replacement group (Table 3). Among the causes of in-hospital deaths, septic shock was the most frequent (50% in the mitral valve repair group vs. 46% in the mitral valve replacement group), followed by heart failure (25% in the mitral valve repair group vs. 31% in the mitral valve replacement group). One death related to neurological complications was observed in the surgical mitral valve repair group and 2 deaths following a major bleeding were recorded in the surgical mitral valve replacement group.

Clinical and echocardiographic follow-up characteristics.

| Variable | Valve repair (n=34) | Valve replacement (n=82) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early outcomes | |||

| In-hospital death n, % | 4 (12) | 13 (16) | 0.57 |

| Infective/sepsis n, % | 2 (50) | 6 (46) | |

| CV n, % | 1 (25) | 4 (31) | |

| Surgical complications n, % | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Others n, % | 1 (25) | 2 (15) | |

| Valve dysfunction n, % | 0 (0) | 5 (6) | 0.14 |

| Follow-up (median 5 years) | |||

| Overall death n, % | 10 (29) | 25 (30) | |

| CV death n, % | 2 (6) | 7 (28) | |

| Re-endocarditis n, % | 1 (3) | 8 (10) | 0.21 |

| Re-surgery n, % | 1 (3) | 5 (6) | 0.48 |

| Bleeding n, % | 0 (0) | 8 (10) | 0.05 |

| Stroke ischaemic/TIA n, % | 0 (0) | 8 (10) | 0.05 |

| Echocardiographic follow up | |||

| LVEF mean±SD | 49±25 | 59±9 | |

| Valve dysfunction n, % | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 0.18 |

Abbreviations: CV – cardiovascular; LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction; SD – standard deviation; TIA – transient ischaemic attack.

Pre-discharge transthoracic echocardiography revealed 1 case of severe peri-prosthetic leak and 4 cases with increased mitral mean pressure gradient (≥10mmHg) in the surgical mitral valve replacement group, while no signs of valve dysfunction were detected in the surgical mitral valve repair group (6% vs 0%, respectively; p=0.14).

During a median follow-up of 5 years, the observed survival rates for all-cause mortality were similar in both groups (75% in the surgical mitral valve repair group vs 77% in the surgical mitral valve replacement group, HR 1.03, 95% CI: [0.88,1.20], p=0.928; Fig. 1). The frequency of cardiovascular-related mortality in the surgical mitral valve replacement group was higher as compared to the surgical mitral valve repair, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (28% vs. 6%, respectively) (Fig. 2). The incidence of recurrence of infective endocarditis was higher in the surgical mitral valve replacement group as compared to their counterparts (10% vs. 3%, p=0.21), but the difference was not statistically significant. Rates of re-intervention were similar in both groups (3% in the surgical mitral valve repair group vs. 6% in surgical mitral valve replacement group, p=0.48). Re-intervention was necessary in 3 patients with recurrence of IE (1 in the surgical mitral valve repair group vs 2 in the surgical replacement group), 1 patient with severe paravalvular leak and 1 patient with severe valvular stenosis and 1 patient with mitral prosthesis thrombosis, all from the surgical valve replacement group. Major bleeding and neurological complications (ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attacks) were significantly more frequent in the surgical mitral valve replacement group (10% vs. 0%, p=0.05 and 10% vs. 0%, p=0.05). At intermediate follow-up significant valve dysfunction was reported only in the surgical mitral valve replacement group (5%, p=0.18) (Fig. 2).

Infective endocarditis is an important clinical challenge, carrying high mortality and morbidity rates. Due to the heterogeneity in presentation and diagnosis of the disease, the management can vary case by case. The most appropriate surgical treatment and its timing should be individualised and based on experienced multidisciplinary endocarditis team.9 International guidelines emphasise that the main aim of surgery is to remove infected structures, to avoid and limit, when possible, the use of prosthetic material, trying to preserve valvular anatomy and haemodynamic function.1 A delayed surgery often leads to progression of the disease, favouring tissue disintegration and involving the structures outside the valve anulus,2 requiring a more complex surgical approach and often poor outcomes. Surgical mitral valve repair is the treatment of first choice in case of primary mitral regurgitation.10 However, in the presence of significant structural damage, such as in IE, surgical mitral repair is challenging. On the other hand, surgical mitral valve repair avoids the use of a prosthetic valve that could represent a risk for infection.3 International guidelines suggest surgical mitral valve repair as technique of choice whenever possible,1,11 but the adoption of this technique for native mitral valve IE remains low.5 Dreyfus et al.4 reported that surgical mitral valve repair performed during the acute phase of IE was a safe and effective option. Over the years, subsequent studies have also demonstrated the results of surgical mitral valve repair in the acute phase of mitral IE in selected populations.5,6,12 A metanalysis by He et al.3 including 17 retrospective studies that compared patients who underwent surgical mitral valve repair versus patients who underwent mitral valve replacement showed that the surgical mitral valve repair group had a lower risk of early and long-term mortality, a lower risk of recurrence of IE but a similar risk of reoperation as compared to the surgical mitral valve replacement group. Despite the optimistic results, it is important to underline that all existing studies are observational, retrospective analyses of selected, small patient cohorts, and outcomes often may be biased because of the selection criteria of patients undergoing one procedure rather than the other.

The feasibility of surgical mitral valve repair in patients with active IE varies significantly across different centres, ranging from 15–20% to nearly 80%.13–17 This wide variability may partially reflect different levels of expertise in different centres as well as differences in patient characteristics. Toyoda et al.5 highlighted that, in “real-word” clinical settings, the individual surgeon variability could range from 0% to 84%. The surgical mitral valve repair rate reported in the present study aligns with the findings of Toyoda at al., and those reported in two different metanalyses,3,18 with approximately 30% of patients in our cohort undergoing surgical mitral valve repair. Pre-clinical characteristics of our population are difficult to compare with those reported in literature, given a variable distribution of comorbidities. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species are the most frequent causative agents observed, which is consistent with the epidemiologic data from the EURO-ENDO registry.19

Heart failure was the most frequent indication for surgery in both groups whereas surgical mitral valve replacement was preferred in case of uncontrolled infection. These results are consistent with those reported by Feringa et al.18 underlining how management of the infection is crucial to the surgical decision. An unsuccessful and incomplete resection of the infected tissue could potentially lead to recurrent sepsis, endocarditis, valvular dysfunction and worse outcomes and therefore, in those specific clinical scenarios, surgical mitral valve replacement is preferred over repair.20 Indeed, in our experience and in agreement with previous results,13,15,16 the presence of a more advanced stage of the disease with the involvement of both leaflets, the presence of severe structural damage and extensive valve destruction, as well as multi-valvular involvement, are all factors that led the surgeon to prefer valvular replacement over valvular repair.

Prior metanalyses3,18 demonstrated significant long-term survival advantages after surgical mitral valve repair compared to surgical replacement in native mitral valve IE. However, we could not clearly observe the same results. In the present cohort, overall 5-year survival rates were comparable between the two groups. Perrotta et al.20 reported that when excluding deaths that occurred during the first postoperative year from the survival analysis, no differences in terms of long-term mortality between the two groups of patients were observed. It is possible that the observed disparity in survival may not be solely attributable to the surgical technique itself but rather to the underlying severity of the disease that it is usually more severe in the surgical mitral valve replacement group.

Moreover, beyond the severity of the primary disease, the poor outcomes associated with surgical mitral valve replacement could be explained by its higher rate of complications, including reinfection,3,18 major bleedings and ischaemic stroke.20 In addition, we also observed a higher rate of valvular dysfunction at discharge and during follow-up.

The present study also showed the excellent functional outcomes of surgical mitral valve repair in this challenging clinical scenario. The functional outcomes of surgical mitral valve repair are strongly influenced by the type of underlying lesion, with involvement of the posterior leaflet or commissural involvement as the main lesions observed in the group undergoing surgical mitral valve repair. It has been described how posterior leaflet involvement is associated with a superior durability of the surgical repair, with a lower rate of recurrent mitral regurgitation as compared to the repair performed when the anterior leaflet is involved.21

LimitationsThis is a retrospective study reporting a single centre experience on mitral valve repair on active IE. Additionally, unmeasured confounders, such as surgeon expertise or variations in postoperative care and differences in the severity of structural valve damage, may have influenced outcomes.

ConclusionsSurgical mitral valve repair for native mitral valve infective endocarditis is safe and feasible when there is no significant structural damage of the mitral valve. At intermediate follow-up, surgical repair is associated with less frequency of recurrence of endocarditis, neurological complications and valve dysfunction as compared to surgical replacement.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestVictoria Delgado received speaker fees from Abbott Structural, Edwards Lifesciences, GE Healthcare, JenaValve, Medtronic, Products&Features, Philips and Siemens and consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

![Kaplan–Meier curve analysis for the all-cause mortality-free survival estimates between surgical mitral valve repair and replacement. Hazard ratio HR 1.03, 95% CI: [0.88, 1.20], log-rank p-value=0.928. Kaplan–Meier curve analysis for the all-cause mortality-free survival estimates between surgical mitral valve repair and replacement. Hazard ratio HR 1.03, 95% CI: [0.88, 1.20], log-rank p-value=0.928.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/11340096/unassign/S1134009625001858/v1_202506250425/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)