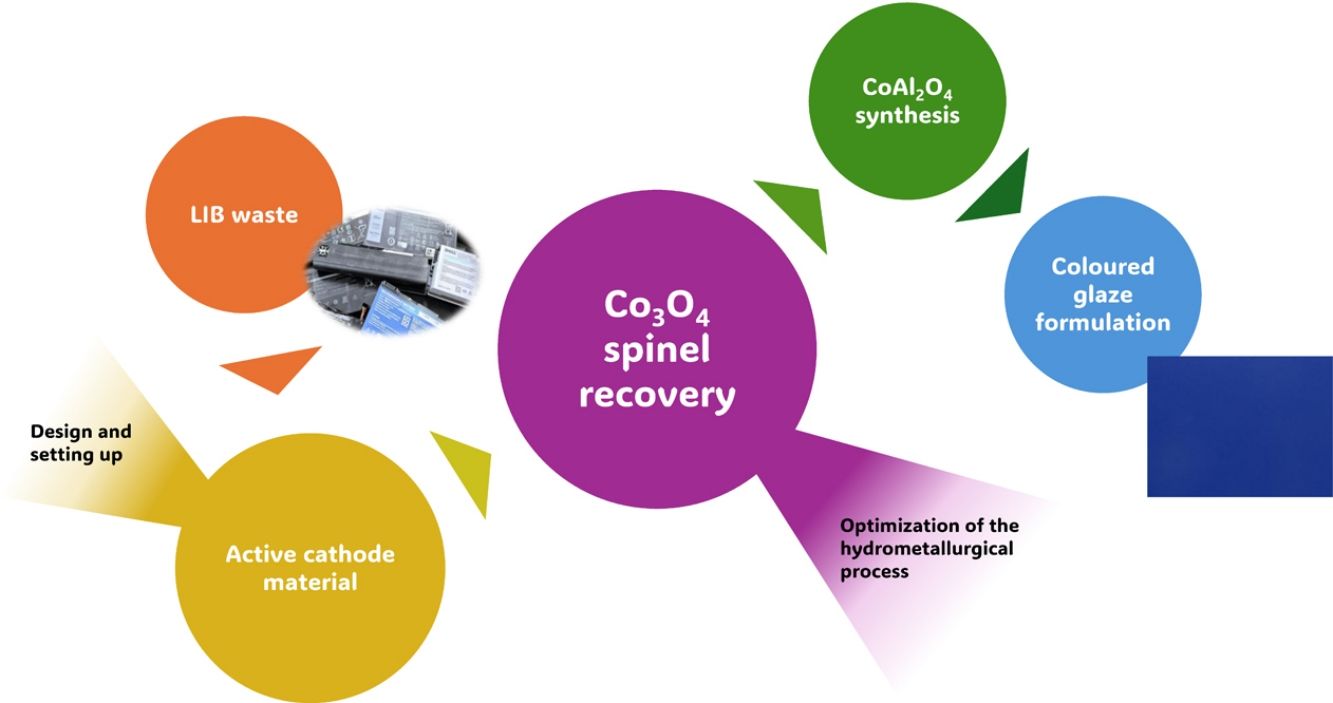

Cobalt is essential to industrial growth, and a low-carbon economy. It is crucial to the production of lithium-ion batteries and national security. Other industrial applications are: superalloys, catalysts, hard metals, ceramics, or magnets. In particular, 5.3% cobalt demand was used in the ceramic sector in 2024, accounting for almost 12 kt. The European Union (EU) relies on imports of refined cobalt, especially from China and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. To ensure strategic autonomy, the EU aims to increase cobalt processing and recycling. This study focuses on the optimization of the leaching process to recover cobalt from spent LIBs with high efficiency and purity for sustainable use. Sulphuric, citric, and nitric acids were selected for the study, varying the concentration of the dissolution, reaction time and temperature, and the solid-to-liquid ratio. The best results were obtained using a 2M HNO3 solution with 4vol.% H2O2 and a 1:50 solid-to-liquid ratio, working at a temperature of 85°C for 60min. The applicability of the recovered cobalt oxide was assessed by its use in the synthesis of a ceramic blue pigment.

El cobalto es esencial para el crecimiento industrial y una economía baja en emisiones de carbono. Es crucial en la producción de baterías ion-litio y para la seguridad nacional. Otras aplicaciones industriales son: superaleaciones, catalizadores, metales duros, cerámica o imanes. En particular, el 5,3% de la demanda de cobalto se utilizó en el sector cerámico en 2024, lo que supone casi 12 kt. La Unión Europea (UE) depende de las importaciones de cobalto refinado, especialmente de China y la República Democrática del Congo. Para garantizar su autonomía estratégica, la UE pretende aumentar el procesado y reciclado de cobalto. Este estudio se centra en la optimización del proceso de lixiviación para recuperar cobalto de baterías ion-litio usadas con elevada pureza para un uso sostenible. Para el estudio se seleccionaron ácido sulfúrico, cítrico y nítrico, variando la concentración de la disolución, tiempo y temperatura de reacción y la relación sólido-líquido. Los mejores resultados se obtuvieron utilizando una disolución de HNO3 2M con 4vol.% H2O2 y una relación sólido-líquido 1:50, trabajando a una temperatura de 85°C durante 60min. La aplicabilidad del óxido de cobalto recuperado se evaluó mediante su uso en la síntesis de un pigmento cerámico azul.

Cobalt plays a vital role in electric vehicle (EV) batteries, which are key to the energy transition. Recognized as a critical raw material, cobalt is integral to achieving climate neutrality. The criticality of a raw material is assessed according to the evaluation of the economic importance (EI) for the European Union (EU) and the supply risk (SR), based on supply concentration at global and EU levels, weighted by a governance performance index, corrected by recycling and substitution parameters.

Projections indicate that by 2050, cobalt demand may surge by up to 350%, largely due to the expansion of electric mobility. Currently, the European Union (EU) relies heavily on imports of refined cobalt from countries such as China and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The European Commission acknowledges that to attain strategic autonomy, there must be a significant increase in cobalt processing within the EU and enhancements in cobalt recycling efforts [2]. In this sense, the European Commission has approved different regulations to establish clear rules in terms of battery recycling, as batteries can turn into a secondary source of critical raw materials for Europe [3] and to ensure a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials [4].

Cobalt is used in many industrial applications, although battery applications account for 76% of cobalt demand and are the dominant driver of market growth. The remaining 24% of cobalt demand is supported by non-battery applications, such as superalloys, which are primarily used in commercial and defense aerospace applications, as well as hard metals, catalysts, or ceramics [5–7]. Although these industrial applications command a lower market share of total demand, they remain an important and strategic demand segment, and they also contribute to the cobalt grew demand in 2024. Regarding the ceramic sector, it accounts for 5.3% of the total demand for cobalt, representing almost 12,000 tons of cobalt consumption in 2024 [6]. The European Union is the second largest producer of ceramics, accounting for 10.4% of global production. Extrapolating the data on cobalt oxide consumption in the ceramics sector with respect to the proportion of European consumption suggests that annual European consumption would be approximately 1200 tons.

Benchmark forecasts a total cobalt demand growth of 7% CAGR, reaching 400,000 tons in the early 2030s. Cobalt supply is expected to grow at a CAGR of 5%, lower than that of the demand, so the faster rate of growth in demand over supply will turn into a cobalt deficit in 2030. So, secondary supplies of cobalt are imperative [6].

It is anticipated that the stockpiles of spent lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) will reach 1.6 million tons by 2030, indicating a significant rise from the 300,000 tons recorded in 2020 [8], due to the growing demand for consumers and EV batteries. LIB waste is regarded as toxic because of the materials utilized in their production, making recycling essential for closing the LIB life cycle and promoting the Circular Economy [9]. Besides, approximately 40% of the emissions from EV production are attributed to LIBs, which heavily reliant on the mining and refining of raw materials. This environmental impact can be reduced by 5–30%, effectively reducing resource and ecological issues to achieve sustainable development. But battery recycling also opens new possibilities in urban mining, where valuable resources are reclaimed from discarded electronic products, contributing to a more sustainable and resource-efficient future. In this sense, cobalt can be extracted from spent LIBs and used as in other industries [10].

The LIB recycling goal is to achieve a sustainable, efficient, and low-cost system to process spent LIBs on an industrial scale as well as achieve sustainability in the global automotive and renewable energy sectors, but many efforts are still needed to translate laboratory methods to industrial plants. Cobalt is located in the composition of active cathode material used in the manufacturing of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). First commercialized batteries used LiCoO2 (LCO) as active cathode material, a compound with 60.2wt% Co in their composition. Considering that the active cathode material represents 20wt% of the battery weight, each battery presents around 12wt% of Co, which can be recovered. Although the battery industry has evolved since first LIB commercialization and new chemistries with lower cobalt content have appeared, it is still worth recovering it.

There is extensive literature related to the recovery of cobalt from different wastes. Almost all the studies related to the recovery of cobalt from lithium-ion batteries use hydrometallurgical methods. Wang et al. [11] designed a process for cobalt recovery from LCO cathodes using EDTA as a co-grinding additive and metal chelate reagent, recovering 98% of Co. However, the experiments were undertaken on active cathode materials manually separated, not evaluating the presence of other metals coming from other parts of the battery that may be present when the separation is undertaken in an industrial plant. Other studies used different inorganic acids (H2SO4, HCl, HNO3) for the leaching of the active material, stating high Co recovery rates and obtaining the active cathode material from spent batteries separated at laboratory scale with different procedures involving shredding and crushing [12–15]. Chen et al. and Wang et al. [16,17] studied the leaching process using pristine material, so that the effect of the contamination from the rest of the components could not be evaluated. Other authors, like Li et al. or Chen et al. [18,19] studied the employment of organic solvents in order to establish an eco-friendly leaching process, although inorganic acids are still being explored because they are more effective for solid dissolution. There are many publications about the recovery of cobalt from LIBs. Still, none of them have tackled the study using an active cathode material separated from the rest of the components using an automatized process at pilot or industrial level, that may introduce new variables to the leaching process, as contaminants from the rest of the parts of the battery will be present in the active powder separated. Besides, few have evaluated the purity of the cobalt obtained, which is as important as the efficiency of the recovery process, as it can determine its applicability.

Therefore, this work aims to design a process to obtain cobalt oxide with high purity from spent lithium-ion batteries and with high recovery efficiencies for being used in the ceramic sector. For that, the leaching process for cobalt extraction will be optimized, studying different variables: type and concentration of the acid reagent used, reaction temperature and reaction time, and the solid-to-liquid ratio. A blue ceramic pigment with the recovered cobalt oxide will then be synthesized to assess its applicability.

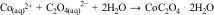

ExperimentalMaterials and reagentsThe study was undertaken with spent LIBs used in laptops of different models and manufacturers collected from various waste managers. Among all the batteries collected, those that presented an LCO chemistry in the cathode were selected for this study. The classification could be undertaken thanks to a previous study in which a database of laptop batteries was created [20], classifying them in terms of the chemistry of the active cathode material used in their manufacturing. For that, the active material was separated manually from the rest of the components and chemically characterized. This characterization was addressed by wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (WD-XRF), for the determination of the majority of the elements, using a PANalytical model AXIOS spectrometer with a Rh anode tube, and 4kW power, and fitted with flow, and scintillation detectors, and eight analyzing crystals, except for Li which determination was carried out by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using an Agilent model 5100 SVDV spectrometer, after submitting the sample to a digestion process.

Laptop batteries are constituted by four to eight cylindrical or pouch cells connected in series or parallel to reach the voltage and capacity required, and are covered by a plastic case, as shown in Fig. 1.

The process for recycling spent lithium-ion batteries involves three stages: pretreatment, separation of the individual components, and recovery of the valuable products.

This study was undertaken with cylindrical cells (model id. 18650). For active cathode material recovery, the first step was the removal of the plastic case with the use of shears in order to reach the individual cells. Then, the cells were discharged to avoid the stored energy from being released abruptly, preventing potential hazards during the next procedures, as fires or explosions. Without prior battery deactivation, the anode and cathode of LIBs with remaining capacity quickly come into contact and cause a short circuit.

For that, cells were immersed in a conductive saline solution of NaCl (5% w/v) for 48h, creating a short circuit between the battery's positive and negative electrodes. Then, the cells were cleaned in a water bath and dried at a temperature of 45°C. After this procedure, all the battery cells presented a voltage below 0.5V.

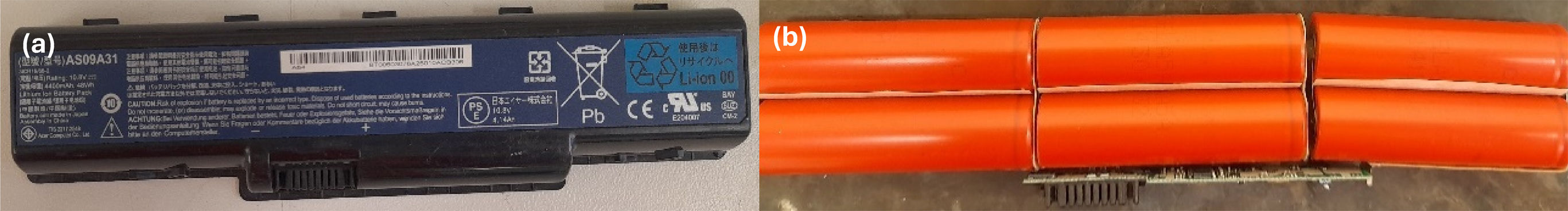

The active cathode material was separated using a process designed and patented by this research group, which involves different processes of shredding, size separation, and thermal treatments [21,22], as shown in the schematic diagram in Fig. 2, the percentages of the recovered materials referred to the cell unit.

Schematic diagram for cathode recovery from spent LIBs. Patented process [22].

The process begins with an initial cutting stage carried out under controlled conditions using blades, aiming to minimize excessive cell damage and reduce contamination of the cathode material. Next, the cells undergo a thermal treatment at temperatures below 500°C to remove the binder, which helps separate the active materials from the remaining components. After heat treatment, the cells are agitated in water to effectively separate the components, followed by particle size separation and additional thermal processes to isolate the desired fraction.

This patented process was scaled up at pilot plant level, permitting the processing of the Li-ion cells in batches of 5kg and obtaining around 1.25kg per batch. The process at the pilot plant level is a semi-automatic process that operates discontinuously, permitting the recovery of approximately 5kg of cathode per working day. Some modifications were introduced for the scaling:

- -

A cutting machine that permitted the cutting of the cylindrical cells continuously was designed and built.

- -

A previous separation step to separate the coarser particles was introduced so that the metallic shells and major part of aluminum and copper foils were separated.

- -

A pumping system was designed to convey the material retained in aqueous medium to a continuous screening system, where a second separation by particle size was carried out, removing the remaining aluminum and copper foils that have a smaller particle size.

- -

A centrifugation stage was introduced to separate the solid material from the water.

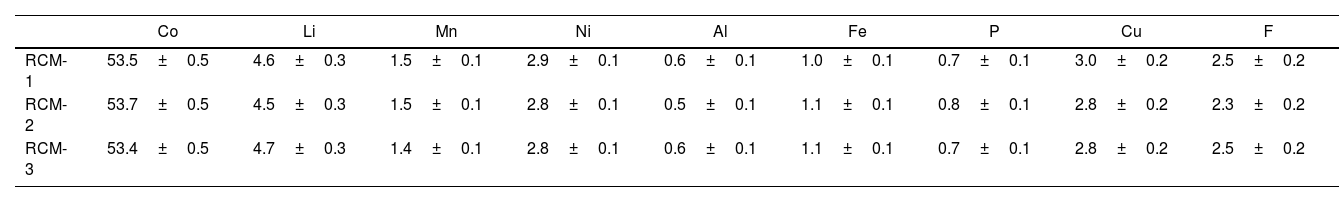

In addition, derived from the separation process, two by-products are also obtained that can be used to recover Cu and Ni, respectively. The by-product enriched in Ni corresponds to the external shell of the cylindrical cell, with 60wt% Ni and accounting for almost 20wt% of the total weight of the battery cell. The by-product enriched in Cu corresponds to the fractions where cathode and anode foils are retained, with 50wt% Cu and accounting for 27wt% of the total weight of the cell. Table 1 shows the chemical composition of three cathode materials obtained from three different batches, together with the standard deviation.

Chemical composition of three recovered cathode materials (RCM) from three different batches (wt%).

| Co | Li | Mn | Ni | Al | Fe | P | Cu | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCM-1 | 53.5±0.5 | 4.6±0.3 | 1.5±0.1 | 2.9±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 1.0±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 3.0±0.2 | 2.5±0.2 |

| RCM-2 | 53.7±0.5 | 4.5±0.3 | 1.5±0.1 | 2.8±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 2.8±0.2 | 2.3±0.2 |

| RCM-3 | 53.4±0.5 | 4.7±0.3 | 1.4±0.1 | 2.8±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 2.8±0.2 | 2.5±0.2 |

Lithium was determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using an Agilent model 5100 SVDV spectrometer after submitting the sample to an alkaline fusion with potassium carbonate followed by acid digestion. Fluorine was analyzed by potentiometry using a Metrohm model 692 pH/Ion meter after alkaline fusion with sodium carbonate followed by aqueous digestion, and the rest of the components were determined by wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (WD-XRF) using a PANalytical model AXIOS spectrometer, preparing the samples as fused beads, using a 50:50 mixture of lithium metaborate and lithium tetraborate as flux in a 1:15 sample/flux ratio.

It is worth noting that the material presents some impurities that come from the rest of the components of the battery: phosphorus and fluorine from the electrolyte, aluminum and copper from the cathode and anode collectors respectively, iron from the external shell, and manganese and nickel can be present due to some NMC cells that could wrongly enter the system. So, this study will be able to evaluate the influence of the presence of some undesirable elements (such as Cu, Al, P, or F) in the subsequent hydrometallurgical process and the suitability of the cobalt oxide recovered for the intended use, in contrast with many other studies that can be found in the literature, in which cathode material manually separated or virgin cathode powders (free from any contaminant) are used for their studies [12,14,15,17,23]. Besides, no significant difference in the chemical composition of the recovered cathodes were observed, showing the robustness of the separation process.

The leaching reagents employed in this study were: sulphuric acid (H2SO4), nitric acid (HNO3), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from Merck, and citric acid (C6H8O7) from Probus. Ammonium oxalate ((NH4)2C2O4) from Alfa-Aesar was used for the selective precipitation of cobalt. All chemical reagents were of analytical grade, and all the solutions at specified concentrations were prepared or diluted using pure water (with a conductivity lower than 3μScm−1).

Co3O4 from Merck was selected for comparison with the recovered Co3O4 obtained from the LCO active cathode material.

Hydrometallurgical process for cathode dissolution and cobalt precipitationHydrometallurgical processing involves the breaking down of the cathode material extracted from used lithium-ion batteries, followed by the selective separation of the components from the resulting leachate. Research [7] shows that extracting metals from spent lithium-ion batteries through hydrometallurgical methods is a viable approach due to its various benefits, such as high recovery rates of metals with purity, low energy requirements, and minimal gas emissions, compared with other methods such as pyrometallurgy. However, the process does produce high amounts of liquid waste. Hydrometallurgical procedures are currently the most common, but it is important to continue exploring this technology in order to reduce not only the toxicity of the leaching agents used but also the amount, reducing both the environmental impact and the cost efficiency.

All experiments undertaken for the optimization of the leaching process were conducted with the recovered cathode referenced as RCM-1. The material was subjected to a dissolution process by stirring in an acidic medium for a given time and temperature and connecting the system to a condenser to avoid the evaporation of the solvent. The leaching process was optimized in order to minimize the amount of insoluble material, as well as taking into consideration the purity of the cobalt oxide obtained. This optimization was undertaken studying the following variables: leaching agent (organic and inorganic), concentration of the leaching agent, solid/liquid ratio, reaction temperature (T), and reaction time (t), as they are considered the main factors affecting the leaching process [24]. The dissolution of the solid material can be favored by the addition of a reducing agent; thus, the addition of H2O2 to the system was also considered.

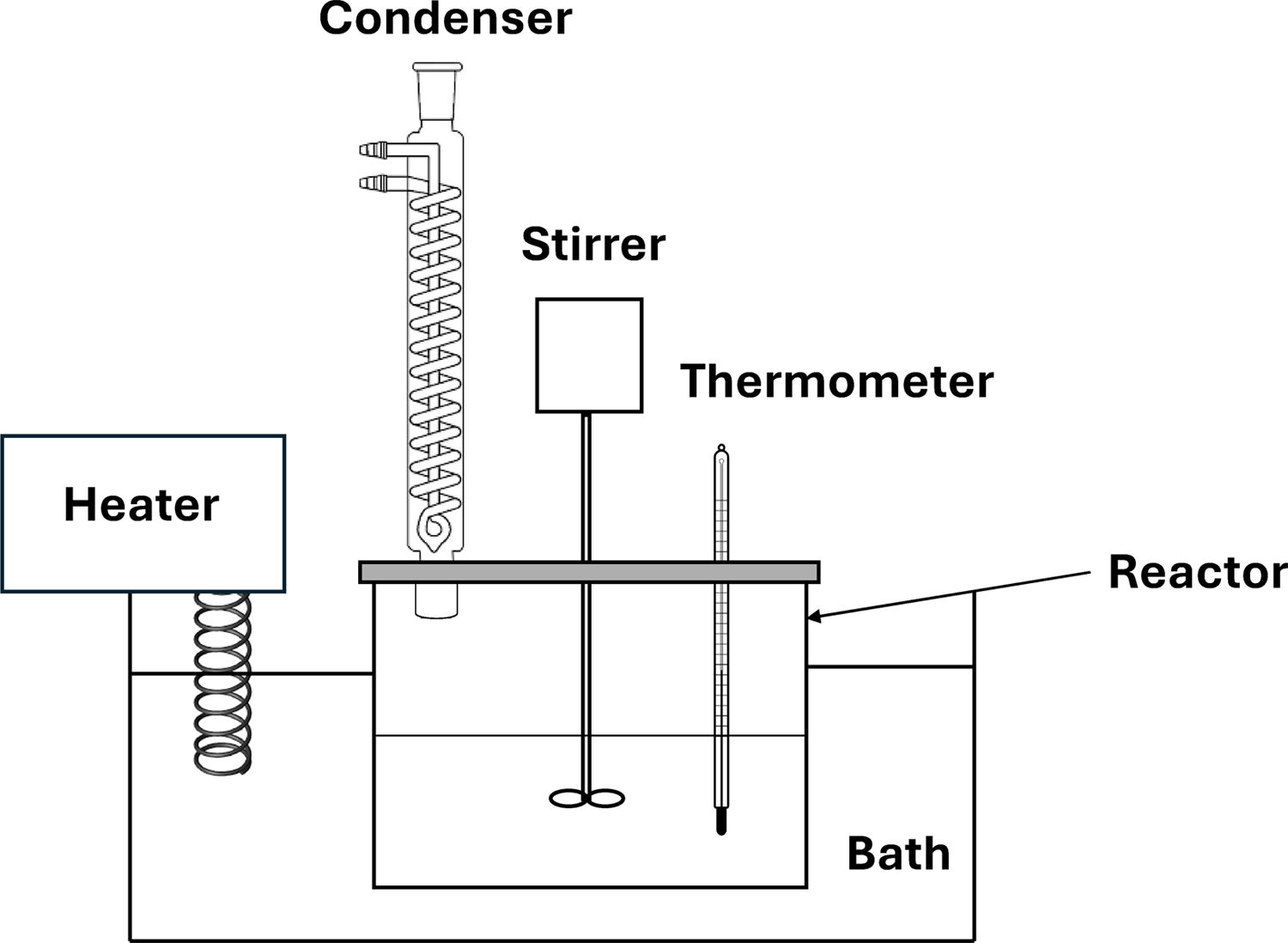

The leaching experiments were conducted in a 500ml Pyrex glass reactor, put inside a thermostat, fitted with a stirrer, a condenser, and a thermometer, as shown in Fig. 3.

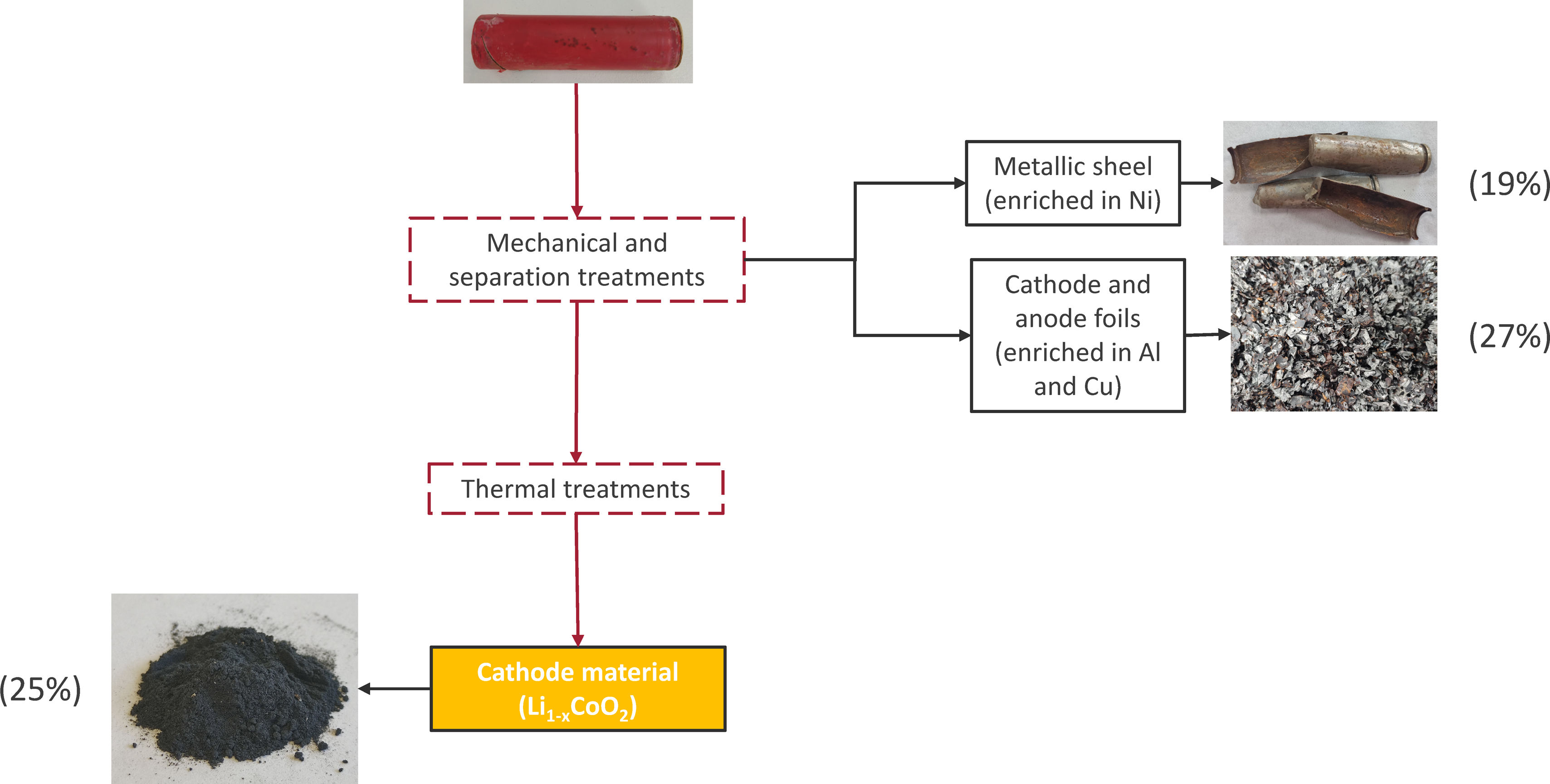

Once the reaction time had elapsed, the slurry was vacuum filtered through a 0.45μm pore size cellulose nitrate filter to separate the leach liquor from the insoluble residue. Cobalt recovery was performed by adding a complexing agent that produces the selective precipitation of cobalt. A 0.5M (NH4)2C2O4 solution was used for cobalt precipitation according to the following reaction:

The mixture of the leach liquor with the complexing dissolution was stirred for 30min at 300rpm and room temperature, and cobalt was recovered as cobalt oxalate (CoC2O4·2H2O) after filtration and drying. Cobalt oxide (Co3O4) was finally obtained by transformation of the former precipitate when heat-treated at a temperature of 600°C in an electric furnace.

Three different leaching agents were selected for this study: H2SO4, C6H8O7, and HNO3, with the addition of H2O2 as reducing agent, or without. H2SO4 and HNO3 were selected for being common leaching agents or solvents, while C6H8O7 was selected for being an organic acid, to reduce the environmental hazard of the process.

Characterization of the recovered Co3O4The Co3O4 recovered after the leaching and precipitation steps was characterized in order to check the purity. The chemical composition was carried out by WD-XRF, preparing the samples as fused beads. Identification of the crystalline phases was conducted by X-ray diffraction (XRD), using an X-ray diffractometer Theta-Theta D8 Advance A25 from Bruker with CuKα radiation (λ=1.54183Å). The XRD data were collected in a 2θ of 5–90° with a step width of 0.015° and a counting time of 1.2s/step by means of a LinxeyEYE detector. The particle size distribution was determined by laser diffraction using a MASTERSIZER 3000 laser diffraction analyzer from MALVERN. Calculations were performed using Mie theory, considering a refractive index of the solid particles to be 1.74 and the absorption coefficient to be 1.0.

Characterization of CoAl2O4 blue pigmentThe Co3O4 was used as secondary raw material in the synthesis of the CoAl2O4 blue pigment, which was introduced in a colored ceramic opaque glaze formulation for porcelain stoneware to study the color development by analyzing the chromatic co-ordinates (L*, a*, b*), and ΔE. For that, glaze suspensions were prepared with 2wt% of pigment and a solids content of 70wt% in a high-speed laboratory mill with alumina balls, using sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) as a binder and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPF) as a deflocculant (3wt% relative to solid). The glaze was then applied over a slipped green porcelain tile and fired at a maximum temperature of 1200°C.

The measurement was carried out using a Macbeth model Colour-Eye 7000A spectrophotometer, measured according to the CIELab system, which represents the sample color on a three-dimensional scale, where each co-ordinate indicates a pair of colours: L* is the lightness axis (black (0) and white (100)), a* is the green (−) to red (+) axis, and b* is the blue (−) to yellow (+) axis. ΔE permits the quantification of the difference between two colors, and it is calculated according to the following equation:

This value is a guidance for quality control and color matching processes, so that a value of ΔE below 1.0 typically indicates an imperceptible color difference to human eye, while values above 2.0 may be noticeable and potentially unacceptable.

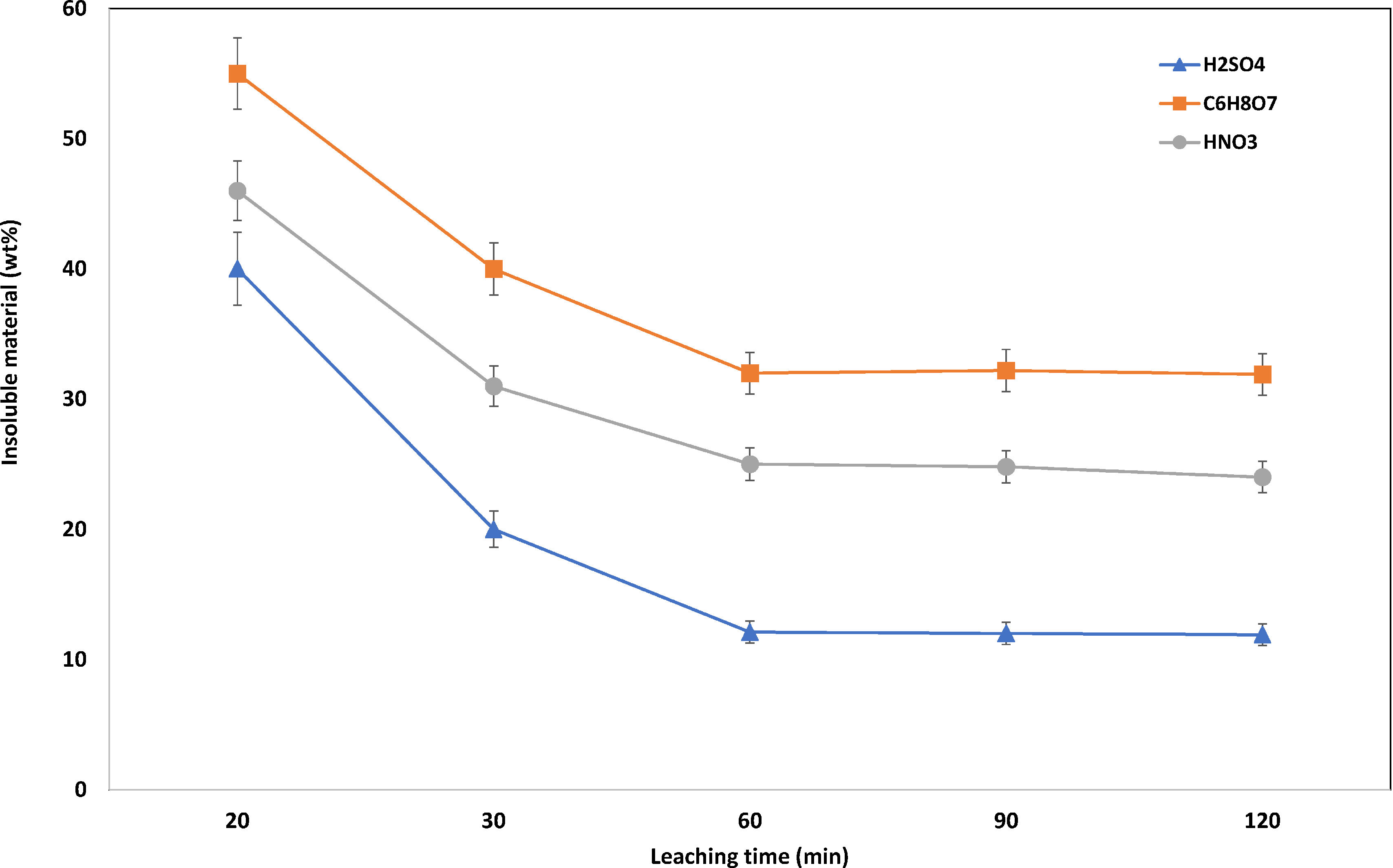

Results and discussionOptimization of the leaching stepLeaching timeThe optimization of the leaching process was evaluated in terms of the dissolution of the cathode material. The effect of the leaching time was investigated at a range of 20–120min with the three leaching agents chosen for this study. The rest of the variables were kept constant: reaction temperature 65°C, acid concentration 1.0M, and a solid-to-liquid ratio 1:20.

As can be seen in Fig. 4, the amount of insoluble material decreases as the leaching time increases from 20 to 60min, remaining constant from 60min to 120min, indicating that leaching equilibrium had been reached within 60min. Moreover, the H2SO4 system presents the highest leaching efficiency as expected, as it is the strongest acid.

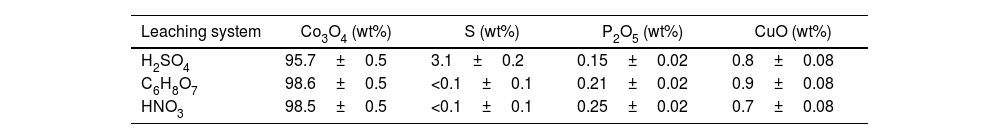

The cobalt oxides obtained after the selective precipitation with the three leaching systems were chemically characterized. Results presented in Table 2 show that the cobalt oxide recovered from the H2SO4 system contained a high percentage of sulfur, which is an undesirable impurity in ceramics, thereby lowering the purity and quality of the cobalt oxide.

Considering these results, although H2SO4 was expected to be the most effective, it was discarded as the Co3O4 recovered afterwards was contaminated with sulphur, precipitated together with cobalt, during the selective precipitation step.

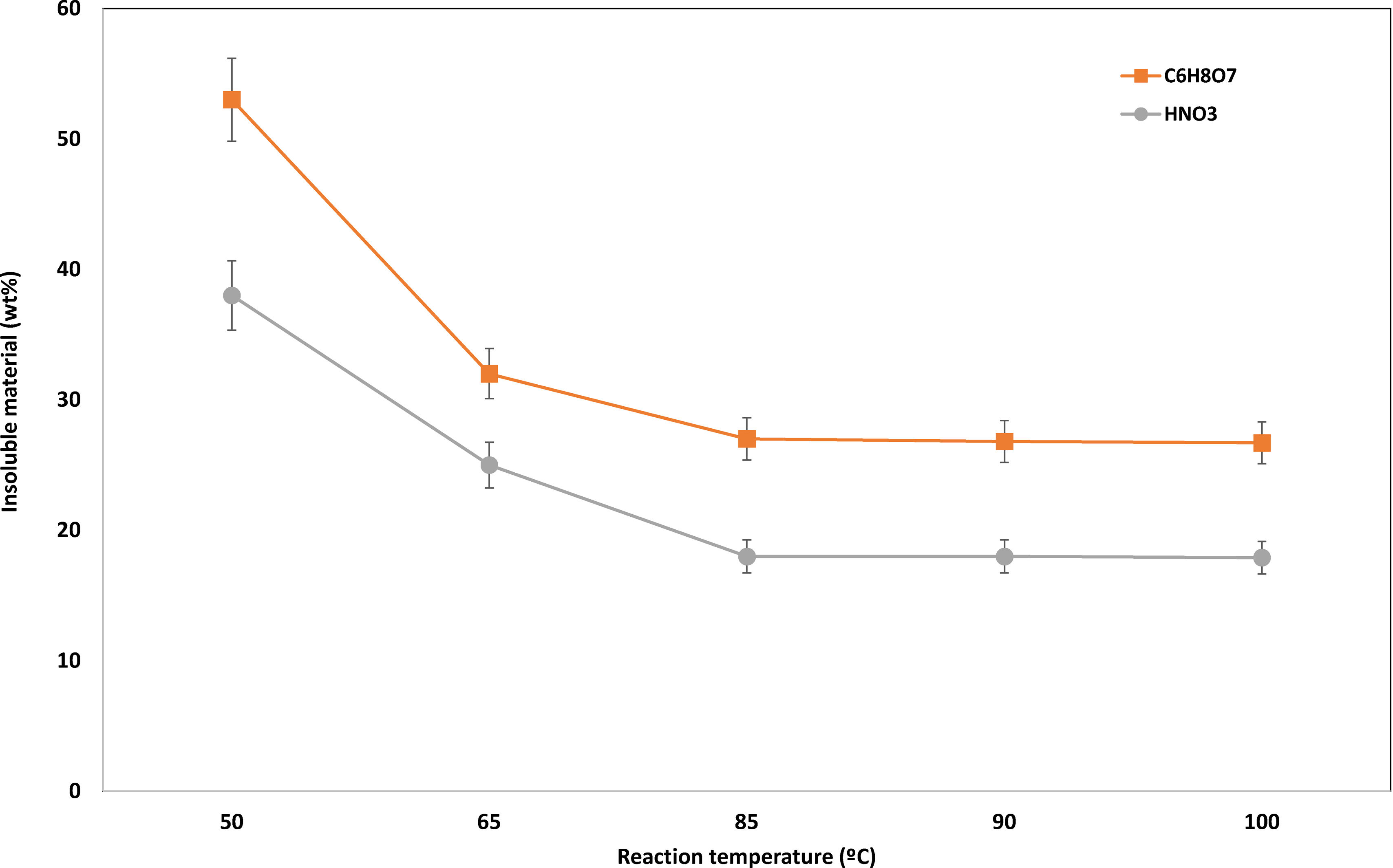

Reaction temperatureReaction temperature effect was studied under conditions of leaching time 60min, acid concentration 1.0M, and a solid-to-liquid ratio 1:20. From the results shown in Fig. 5, it can be stated that reaction temperature presents a significant effect on the solubility of the material as a steady decrease in the insoluble material can be observed from 50 to 65°C, reaching the minimum value at a temperature of 85°C.

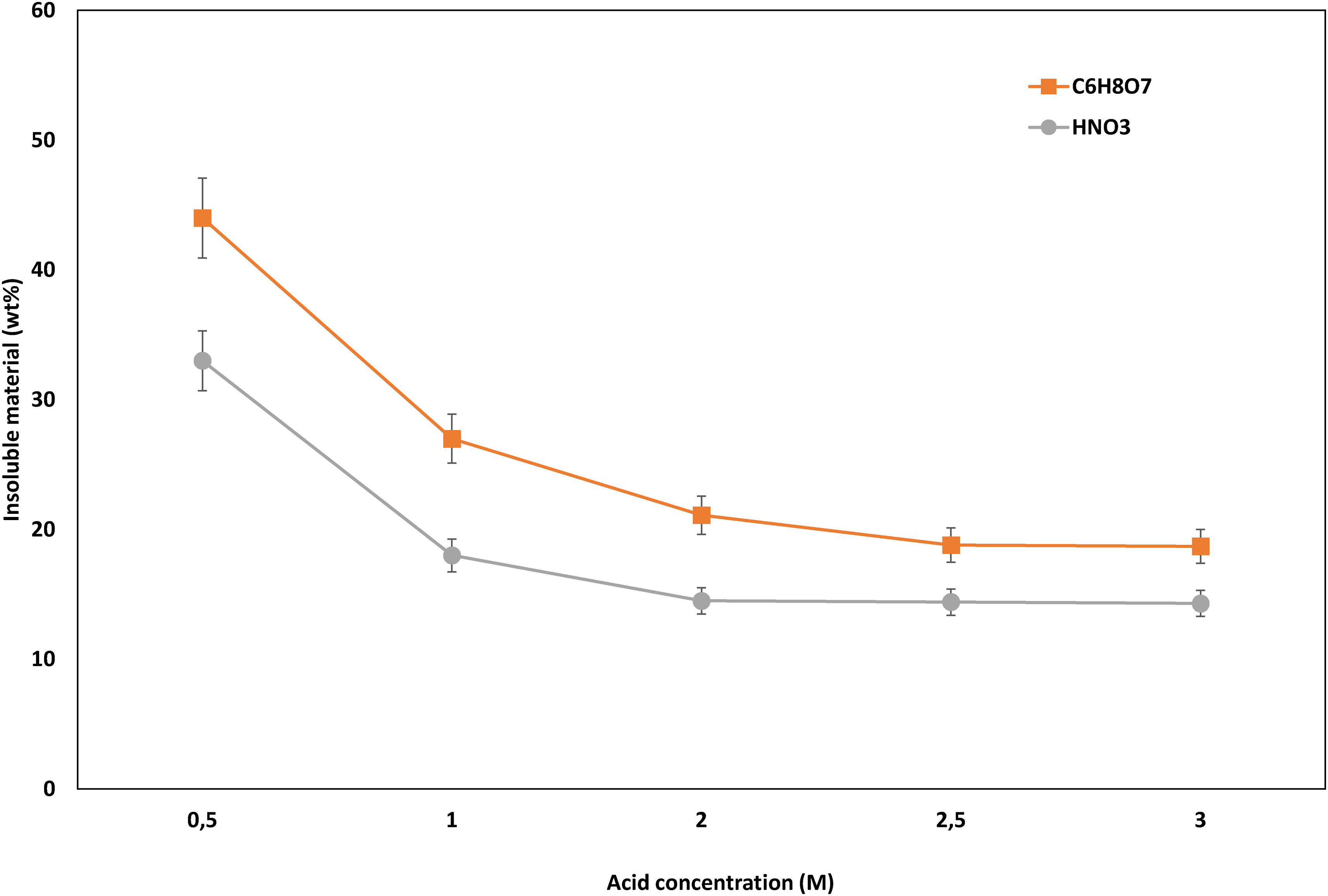

Acid concentration and use of reducing agentFig. 6 illustrates the effect of acid concentration on the leaching of the LCO cathode. These experiments were conducted under conditions of leaching time 60min, temperature 85°C, and solid-to-liquid ratio 1:20. It can be observed that the insoluble material decreases significantly from 0.5 to 1M, this reduction being less significant with subsequent concentration increases. Minimum values of insoluble material were reached with an acid concentration of 2M for HNO3 and 2.5M for C6H8O7.

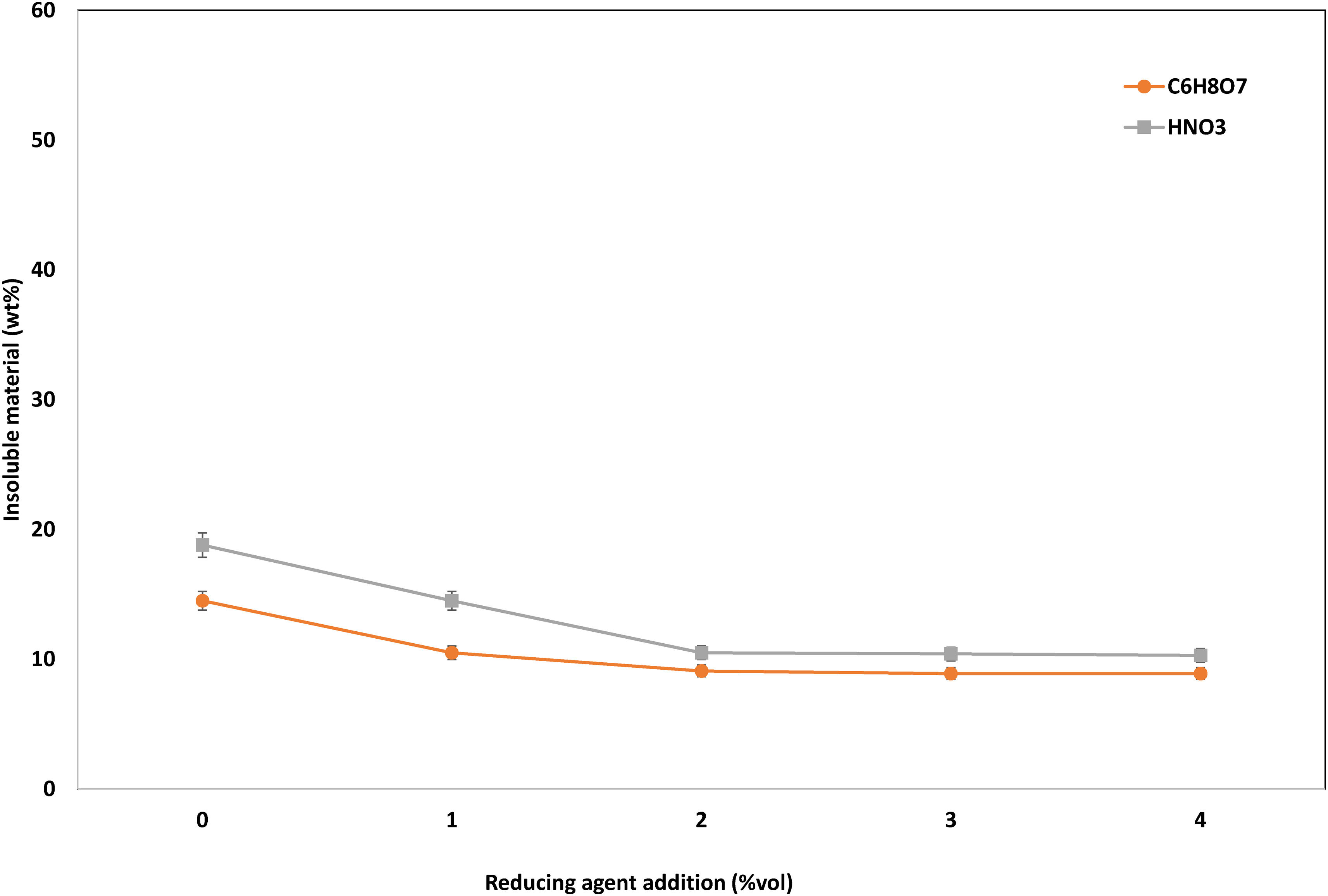

Then, the effect of the use of a reducing agent, H2O2 in particular, was assessed. As can be seen in Fig. 7, the insoluble material without the dosage of reducing agent is almost 19wt% in citric acid media and 14wt% in nitric acid media. With the addition of 2vol.% of H2O2, the insoluble material could be reduced to 10.5wt% and 9.1wt%, respectively.

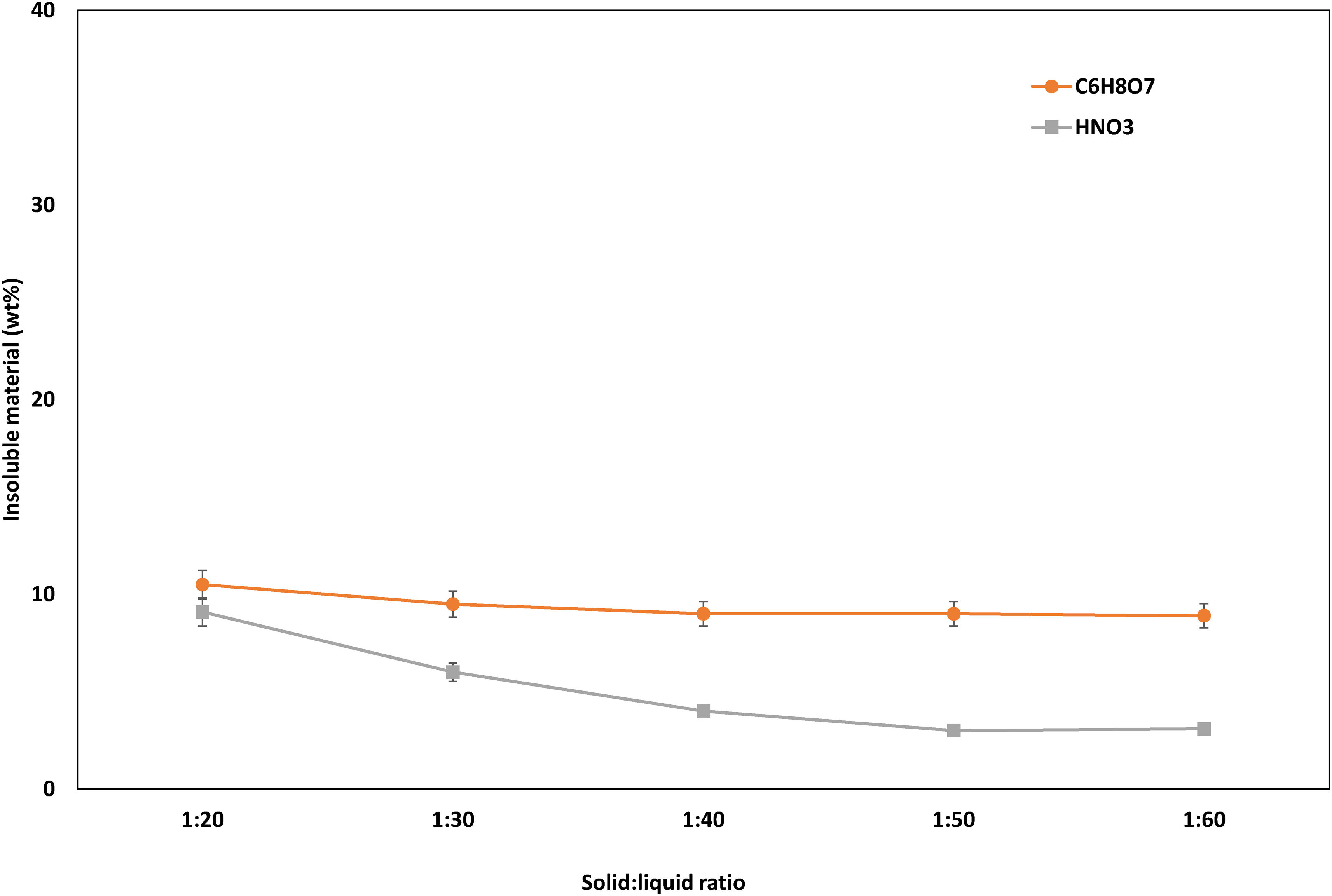

Solid:liquid ratioThe solid-to-liquid ratio or slurry density is also a key player in the leaching process. So, its effect on the efficiency of the leaching process was also evaluated. Results are collected in Fig. 8.

The leaching efficiency when using citric acid showed a slightly improvement from 1:20 to 1:30, while a further reduction of the solid:liquid ratio did not lead to a decrease in the amount of insoluble material. In contrast to this, when using nitric acid as a leaching agent, a considerable improvement of the leaching efficiency was observed with the decrease of the solid:liquid ratio, reaching a 3wt% of insoluble material with a solid:liquid ratio of 1:50.

After the set of experiments undertaken, the established optimum conditions were the following: 2M HNO3 solution, reaction time 60min, reaction temperature 85°C, 2vol.% H2O2, and a solid:liquid ratio 1:50.

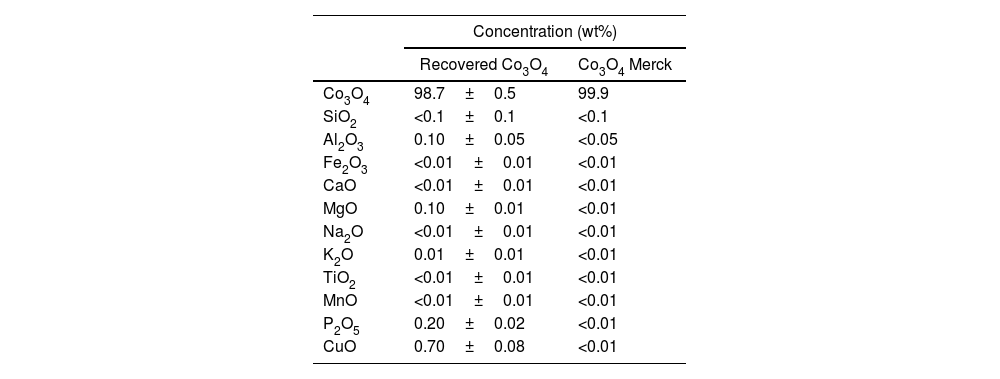

Recovery and characterization of Co3O4After reaching the optimal leaching conditions, the recovery of Co3O4 was carried out with the addition of (NH4)2C2O4 for its selective precipitation, followed by a calcination process at a temperature of 600°C. The selective precipitation of Co3O4 was undertaken with the leachate obtained under the optimized conditions, as it had previously demonstrated that there was no difference in composition when using HNO3 or C6H8O7. Table 3 shows the chemical composition of the Co3O4 recovered, together with the standard deviation, compared with Co3O4 from Merck.

Chemical composition of the recovered Co3O4.

| Concentration (wt%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Recovered Co3O4 | Co3O4 Merck | |

| Co3O4 | 98.7±0.5 | 99.9 |

| SiO2 | <0.1±0.1 | <0.1 |

| Al2O3 | 0.10±0.05 | <0.05 |

| Fe2O3 | <0.01±0.01 | <0.01 |

| CaO | <0.01±0.01 | <0.01 |

| MgO | 0.10±0.01 | <0.01 |

| Na2O | <0.01±0.01 | <0.01 |

| K2O | 0.01±0.01 | <0.01 |

| TiO2 | <0.01±0.01 | <0.01 |

| MnO | <0.01±0.01 | <0.01 |

| P2O5 | 0.20±0.02 | <0.01 |

| CuO | 0.70±0.08 | <0.01 |

The main difference between recovered and commercial Co3O4 was the presence of CuO in the recovered material, which comes from the copper foil present in the LIB anode.

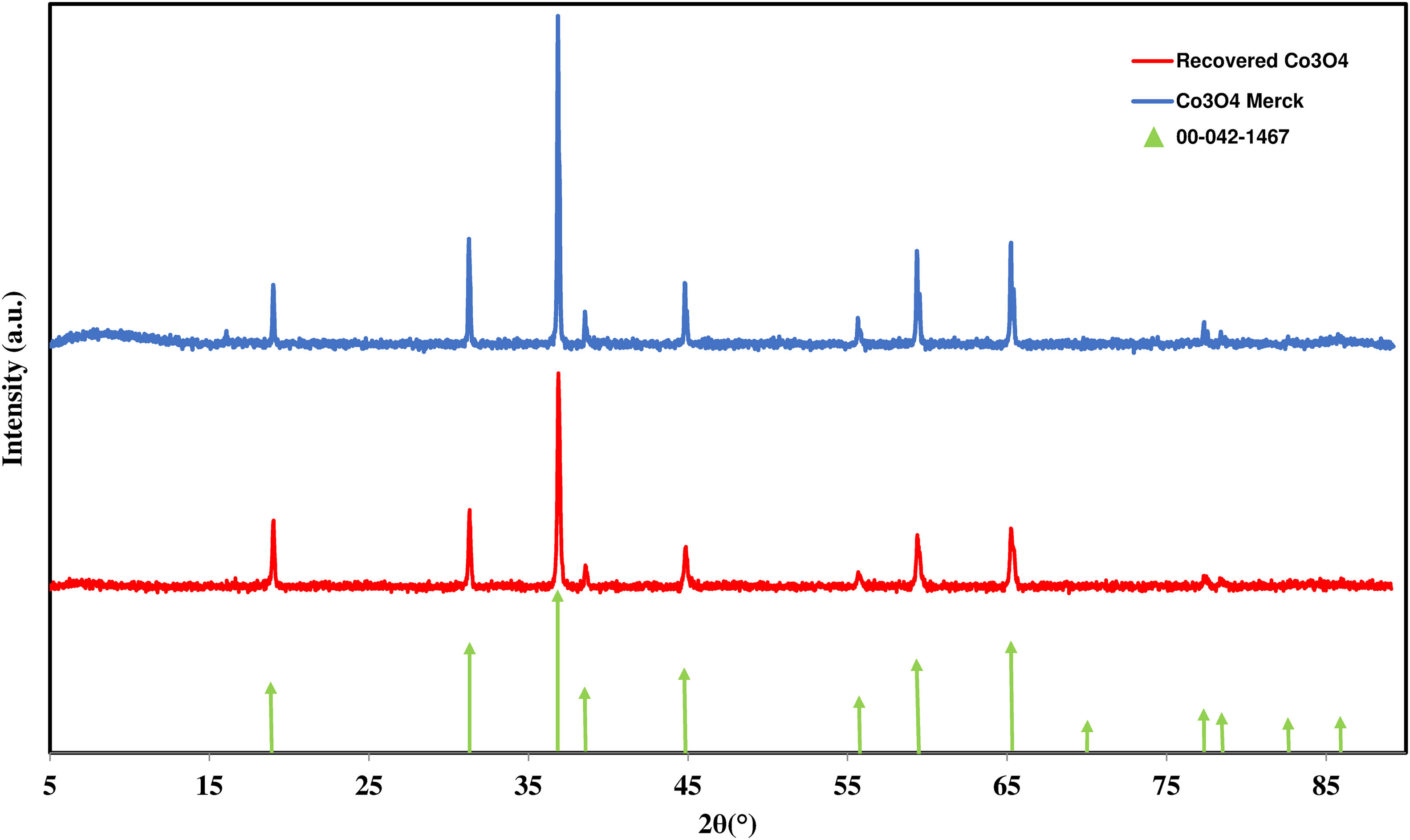

Apart from the chemical composition, phase identification was also undertaken in order to check phase similarity with the commercial. The XRD patterns of the recovered and commercial cobalt oxides are given in Fig. 9, the only crystalline phase identified being indexed as Co3O4 (spinel structure) (ICDD 00-042-1467).

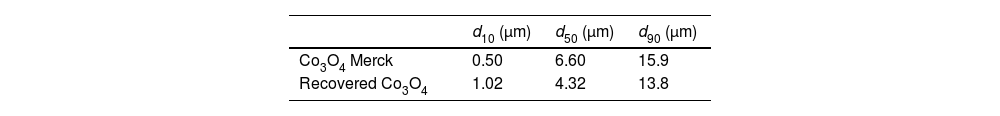

The characterization was completed by determining the particle size distribution. The results of the recovered Co3O4 were compared with the commercial Co3O4, shown in Table 4.

No significant differences in the values for the characteristic diameters were observed compared with the commercial Co3O4 analyzed.

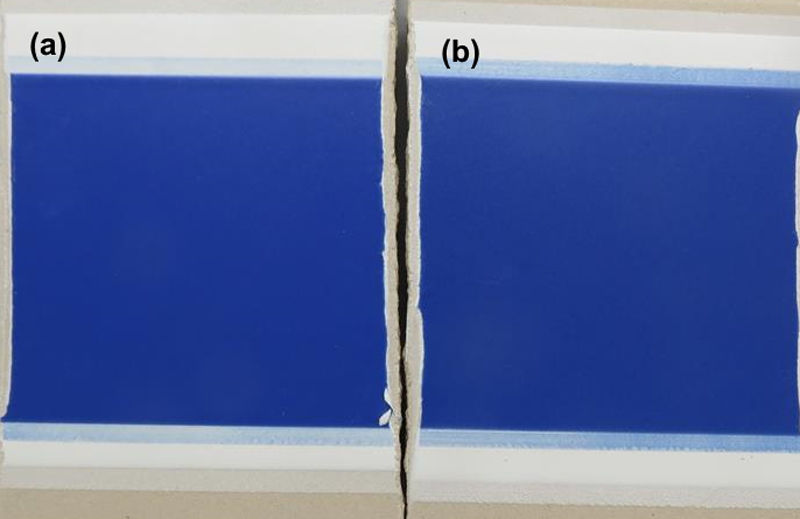

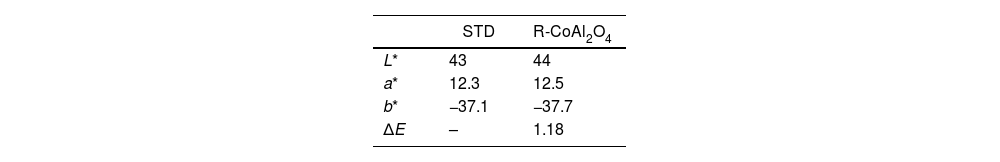

This recovered Co3O4 was used in the synthesis of a blue cobalt pigment (R-CoAl2O4), which was incorporated afterwards in a glaze composition and applied over a slipped unfired porcelain tile, showing an appropriate color development (Fig. 10). Table 5 shows the results obtained in the measurement of the chromatic co-ordinates, once the tile fired at 1200°C, compared with a standard (STD).

The value of ΔE is close to 1, meaning there are no differences in the developed colour when using R-CoAl2O4 compared to the standard and that the human eye cannot perceive the difference, as it can be observed in Fig. 10. These results demonstrate that the impurities present in the recovered Co3O4 do not affect colour development.

ConclusionsThree different leaching agents were tested: sulphuric, citric and nitric acid. Of the three, the one with the highest dissolving power for the active material of the cathode turned out to be the sulphuric acid. However, it was discarded as sulphate anion precipitated together with the cobalt during the precipitation step with oxalate, so that apart from cobalt oxide, cobalt sulphate was also obtained, which is undesirable in the synthesis of pigments or any other industrial application.

From an environmental point of view, citric acid is the greenest. However, its effectiveness in the dissolution process was not adequate as almost 10% of the material remained insoluble.

The use of nitric acid enhanced the dissolution efficiency of the starting material and cobalt recovery, and it was considered the most suitable method in the current research.

The presence of a reducing agent such as H2O2 favored the dissolution process of the active cathode material by reducing Co(III) to Co(II), which is much more soluble in an acid medium.

With the optimized chemical process, 97% of the starting material was dissolved. Furthermore, the purity of the recovered product was adequate to be used in the synthesis of ceramic pigments, as no significant differences were obtained in the colour development, as demonstrated by the value of ΔE.

The economic viability of this process will depend on the price of cobalt as well as that of the additives necessary for its leaching and precipitation. In any case, the applicability of this process at an industrial level will be constrained by the need to comply with European legislation regarding the minimum amount of recycled material that new materials must contain shortly.

Uncited reference[1].

This study was supported by the Valencian Institute of Business Competitiveness (IVACE) under the Research, Development and Innovation program, through project IMDEEA/2019/13, through the European Regional Development Funds (ERDF).

![Schematic diagram for cathode recovery from spent LIBs. Patented process [22]. Schematic diagram for cathode recovery from spent LIBs. Patented process [22].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/unassign/S0366317525000676/v1_202512300430/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)