Annually, construction and demolition waste (CDW) represents one-third of the EU's waste generation. Due to its sheer volume and low-value applications, there is growing interest in its valorisation for new building products. One promising avenue is the incorporation of CDW in recycled ceramic tile production, though this remains largely unexplored at the pre-industrial level. This research examines the viability of pre-industrial-scale production of recycled ceramic tiles with a high content of CDW. CDW materials from a management plant, including ceramic waste (tiles) and mixed debris (construction ceramics and concrete), were processed to create compositions containing up to 10wt% mixed debris. Virgin clay was added in different proportions, resulting in 55, 70, and 100wt% CDW compositions. Results show that spray-dried characteristics allow tile production with up to 70wt% recycled content. The compositions containing 70 and 55wt% CDW were tested pre-industrially, fired at 1145–1155°C. The 55wt% CDW mixture achieves characteristics comparable to those of pre-industrial ceramic tiles, producing novel recycled products with high waste content. These tiles had a flexural strength of >41N/mm2, surpassing the market standard for porcelain stoneware (35N/mm2), and water absorption of 12%, meeting wall tile specifications. An economic and environmental assessment highlights the benefits of using CDW in ceramic tiles, highlighting the potential for an environmentally responsible and resource-efficient approach within the tile industry, while minimising environmental impact and preserving natural resources.

Anualmente, los residuos de construcción y demolición (RCD) representan un tercio de la generación de residuos de la Unión Europea. Debido a su gran volumen y a sus aplicaciones de bajo valor, existe un creciente interés en su valorización para nuevos productos de construcción. Una vía prometedora es la incorporación de RCD en la producción de baldosas cerámicas recicladas, aunque este proceso aún se encuentra en gran parte inexplorado a nivel pre-industrial. Este estudio investiga la viabilidad de producir baldosas cerámicas recicladas con un alto contenido de RCD a escala pre-industrial. Los materiales de RCD procedentes de una planta de gestión, incluyendo residuos cerámicos (baldosas) y escombros mixtos (cerámica de construcción y hormigón), se procesaron para crear composiciones con hasta un 10% en peso de material de escombro mixto, siendo el restante RCD principalmente compuesto por baldosa cerámica descartada. Se añadió arcilla virgen en diferentes proporciones, obteniendo composiciones con un 55, 70 y 100% en peso de RCD. Los resultados muestran que las características del secado por pulverización permiten la producción de baldosas en verde con hasta un 70% en peso de contenido reciclado. Las composiciones con un 70 y un 55% en peso de RCD se probaron pre-industrialmente, cocidas a 1145-1155°C. La mezcla de RCD al 55% en peso logra características comparables a las de las baldosas cerámicas pre-industriales, lo que da lugar a nuevos productos reciclados con un alto contenido de residuos. Estas baldosas presentaron una resistencia a la flexión de >41N/mm2, superando el estándar del mercado para el gres porcelánico (35N/mm2), y una absorción de agua del 12%, cumpliendo con las especificaciones para revestimientos. La evaluación económica y ambiental desarrollada destaca los beneficios del uso de RCD en baldosas cerámicas, demostrando el potencial de un proceso más sostenible y circular en la industria cerámica, a la vez que reduce el impacto ambiental y conserva los recursos vírgenes.

The ceramic industry generates €27.8 billion in production value and employs more than 338,000 people across the EU [1]. It is an intensive sector in the consumption of raw materials and energy, with ∼1% (19Mt/y) of the total CO2 reported on the Emissions Trading System in this community [2]. These emissions primarily result from energy-intensive operations, including fuel combustion during the spray drying and firing stages, mineralogical changes in the clay, and transportation activities [3]. Among the ceramic products, ceramic tiles were produced in ∼18,399–16,377Mm2[4], which is a notorious part of the ceramic industry itself. Nevertheless, the ceramic tile sector is being mobilised for a transition to greener pathways, with different actions such as environmentally friendlier ceramic manufacturing processes (e.g. heat recovery facilities in dryers [5], microwave-assisted drying and firing [6], hydrogen fuelling, etc.), advanced options for raw material extractions, and ceramics waste valorisation comprising recycling activities [7]. Among them, the use of alternative materials to virgin resources has attracted special interest due to the variability and versatility of the replacement possibility.

The ceramic industry has been adopting a “zero-waste production” since the 90s. In this, 65% of their own generated waste is redirected towards its production line in a 5wt% proportion [8–10]. Not limited to this, other external wastes are being regarded at a research level, such as residues from mining activities [11], glass steel waste [12], thermal processes [13], the metallurgical sector [14], wastewater treatment [15], municipal solid waste [16], and paper waste [17]. Hitherto, studies have tried to fit a type of waste into production by partially replacing one or all raw materials. However, despite the wide variability of these materials, there is minimal information about construction and demolition waste (CDW) for this purpose [18]. Therefore, it is still necessary to determine if this type of waste is viable for the manufacture of ceramic tiles at the pre-industrial level and what processes should be followed for its recovery.

The term CDW refers to construction-related waste, including rubble, generated from building, demolishing, renovating, or reconstructing structures. It consists mainly of those materials used for building and includes excavated soil [19]. This category of waste accounts for one-third of the total waste generated in the EU by weight [20], which is translated into 640Mt in 2020 in this region [21]. Their main use is low-added-value purposes such as road pavement and excavation filling. However, due to its physicochemical properties, it represents a potential source of secondary material to produce new building materials, not only giving a second life to these waste materials but also reducing the amount of new raw material needed for the construction of new building products [22]. In this sense, numerous scientific studies address the use of them in a wide variety of building materials, being the most popular being their introduction in the partial substitution of concrete or bricks [23–25]. However, regarding the utilisation of the mineral component of CDW in ceramic tile manufacturing at a high TRL (i.e. >6), there are only two publications that explore its viability to date, even though its use would improve the ceramic tile's circularity and hence its sustainability. Nevertheless, the difficulty of preserving the demanding properties of ceramic tiles poses a challenge when using waste in high proportions. Vidoni et al. [26] produced monolithic ceramics employing as-received demolition debris, mixed or not with calcined waste such as municipal sewage sludge and bottom ash, obtaining good mechanical properties, residual porosity, and water absorption values. Later, Acchar et al. [27] explored the use of real CDW coming from a specific demolition, consisting of ceramic rejects and cement-based leftovers, to successfully create new bricks and tiles with 10wt% of 20wt% CDW, respectively.

Despite these advances, what separates the ceramic tile industry from using CDW as a secondary raw material? According to several studies, the main technological and economic challenges are (i) the sorting of the different waste materials due to their heterogeneity, which difficult the availability of robust and reliable secondary materials [28]; (ii) the lack of scientific studies that explore their viability, possibilities, and limitations [18]; (iii) the economic advantages compared to virgin materials, which are abundant and usually at very low prices; and (iv) the social barrier that the recycled materials encompass because of their general association with lower quality products [29]. One of the main challenges regarding the use of CDW in industrial recycling processes is the margin of uncertainty of its composition. The large number of factors influencing this waste results in high heterogeneity. Among these factors, probably the most significant are the absence of management policies, the materials being bonded together due to their irreversible installation, and the location where they were generated, among others.

In this sense, this work assesses the feasibility of achieving pre-industrial production of a ceramic tile that contains a representative amount of actual CDW. For this purpose, the challenges mentioned were regarded, from waste collection to pre-industrial production. Real CDW were gathered and characterised to establish a composition suitable for obtaining the ceramic piece. This waste was processed at pre-industrial level to produce spray-dried material of the appropriate composition. Three main compositions with up to 30wt% virgin clay content were evaluated on a laboratory scale to establish their feasibility. Once the necessary parameters, such as the firing cycle and virgin clay content, were settled, ceramic pieces were obtained in a ceramic tile factory, containing 30 or 45wt% of virgin clay. All the process stages were developed in nearby plants, located in Castellón, Spain, notably reducing the carbon footprint derived from the transportation of the raw materials. The resulting recycled ceramic tiles were evaluated using standard technical parameters such as density, water absorption, and mechanical properties. Finally, an economic and environmental impact study was conducted on the adoption of this new environmentally friendly route, compared to the standard industrial process, revealing the advantages that the implementation of this waste in the ceramic industry would be significant.

Materials and methodsThe flowchart shown in Fig. 1 schematises the process followed to produce pre-industrial recycled ceramic tiles by incorporating CDW. The process began with the steps of waste collection, material gathering, material sampling, and characterisation. Then, the CDWs were conditioned by dry-milling, wet-milling, and spray-drying, followed by prototype production and laboratory-scale validation. Next, the selected ceramic compositions were processed at a pre-industrial level, which involved dry-milling, composition adjustment, wet-milling, and spray-drying. Pre-industrial production was performed after the laboratory-scale validation tests. The resulting product was evaluated economically and environmentally. The different stages are detailed below.

The employed waste came from a Spanish waste management plant (Noulas Reservi, S.L.) located 4.3km from the ceramic manufacturer. In this management plant, two main types of residues were chosen: ceramic aggregates, named “CER” hereafter (Fig. 2a and b), and mixed demolition aggregates, named “MIX” (Fig. 2c and d). The former corresponds to discarded ceramic material (CER), making it impossible to differentiate from discarded material from the ceramic industry located nearby (i.e. pre-consumer waste) or post-consumer ceramic material, derived from construction, demolition, and/or refurbishment activities. Nevertheless, once this material is stocked in the management plant, it is comparable with post-consumer waste characteristics, where the composition becomes unknown and uncontrollable. The MIX category of waste refers to demolition debris known as ‘ceramic or mixed recycled aggregate.’ According to Spanish waste and contaminated soil regulations (Laws 22/2011 and 5/2013 [30]), this material must contain a minimum of 65% by weight of brick and silico-calcareous brick, which may be combined with concrete. It is not possible to determine the exact quantity of each material with the technology available to date. However, this specific debris exhibits a composition qualitatively predominant in ceramic building materials, such as bricks, which is a key characteristic for the present purpose. The rest is mainly cement-based material (i.e., concrete and mortar), with a minor presence of ceramic tiles. At the recycling facility, foreign substances such as plastics, metals, wood, paper, gypsum-containing materials, and other contaminants have been manually extracted; however, the process may not fully remove all impurities. In this facility, the first conditioning of the residues is undergone to obtain an average size of ∼3cm following its mechanical processing (see the resulting material's aspect in Fig. 2b and d).

For the characterisation of the materials, eight FIBCs (flexible intermediate bulk containers) of 1400–1500kg of each type (i.e., CER and MIX) were collected [31]. Then, approximately 500g of three different parts of each FIBC were collected to obtain a representative sample for their characterisation. The aliquots were labelled after CER or MIX for the ceramic or mixed waste, respectively, a number referring to the FIBC and a last letter that denotes the part of the FIBC: L: left, T: top, and R: right. For example, CER1L corresponds to the ceramic residue found in the left part of the FIBC number 1.

These fractions were characterised as follows: First, each aliquot was qualitatively inspected for the first material evaluation. In this inspection, foreign materials were identified but not removed, to replicate a real scenario. Then they were comminuted in the laboratory by their dry milling using a WC ring mill pulveriser (Siebtechnik, 1min milling stage, 900rpm rate) with a and wet milled using a rapid mill of alumina jar (Heramika, 20min, 2cm alumina balls) with, using water as the solvent and 0.4wt% of sodium tripolyphosphate as a dispersant. Next, the material was dried and sieved through a 100μm sieve. Ball wear after 12h of wet milling of each composition was measured by their difference in weight. The powder was examined using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) with a MagiX spectrometer (Philips), applying the IQ+ semi-quantitative calibration method and Li2B4O7as a flux agent. The materials’ loss on ignition was measured by exposing them to 1000°C for one hour in a muffle furnace. Particle size was assessed using a Mastersizer S (Malvern) with a He–Ne laser (λ=632.8nm), on an ultrasonically dispersed powder.

Material conditioningThe CDWs were comminuted and spray-dried in a pilot plant located in Castellón, Spain, using the total content of each FIBC. The chosen proportions of residues were mixed while conditioning by their comminuting at the pilot scale as follows. The two types of residues were mixed in a CER/MIX ratio of 89/11. Then, the debris was conditioned by dry and wet milling to produce a ceramic slip, followed by the spray-drying step. The material fractioning was done by a dry hammer mill to decrease debris to <2mm in diameter. Sodium tripolyphosphate was added as a dispersant in the wet ball milling step (0.4wt%). Three compositions were generated with different contents of kaolinitic virgin clay: 0, 30, and 45wt%, named 100CDW, 70CDW, and 55CDW, according to the CDW content. These compositions were spray-dried in equipment with a capacity of 500–600kg/h of water removal (pilot-plant spray drier). The resulting material was studied in terms of (i) Particle size distribution by He–Ne laser (λ=632.8nm) using a Mastersizer S (Malvern), on an ultrasonically dispersed powder. (ii) Sphere morphology and dimensions by an Optical Microscope/3D Profilometer (Zeta Instruments). Image J software was used for particle count analysis, measuring at least 300 spheres. (iii) Flowability was determined by using a Hall flowmeter following ISO 14629:2012. (iv) Apparent bulk density of the spray-dried powder and the pressed compact (before firing). (v) Flexural strength of the unfired compact following ISO 10545-4.

Validation testsThe 70CDW were evaluated at a laboratory scale before their pre-industrial scaling. For this, the compositions were uniaxially pressed at 420kg/cm2 in 3cm×8cm rectangular moulds using a Mignon-ssea hydraulic press (Nannetti). The green bodies were evaluated in terms of density and flexural strength. Flexural strength was assessed employing an MTS system testing machine using a 5kN load, following the ISO 10545-4. Then, they were fired in an air atmosphere using a rapid cycle that imitates the industrial one in an electric furnace (Pirometrol) at different temperatures ranging from 1110 up to 1200°C (The 1200°C cycle is displayed in Fig. 3 as an example) after the first evaluation by dilatometry analysis (Netzsch, 402 EP model). Once fired, density, linear shrinkage, mass loss, water absorption, and flexural strength of the specimens (following ISO 10545-3 and 4) were systematically recorded. For internal sample comparison purposes, a standard commercial spray-dried composition of porcelain stoneware tile is used, named “STD”. This material is known as the top-quality product referred to as a ceramic tile, being classified as BIa group based on ISO 13006:2018 (flexural strength >35N/mm2 and water absorption <0.5%) [32].

Pre-industrial firing cycle tests were performed on unglazed 70CDW tiles pressed at 420kg/cm2 in 50cm×50cm×10.5cm. Two thermal cycles were tested, long (69min in total) and short (46min in total), used for red body tile industrial cycles, with a dwell temperature of 1155 and 1145°C, respectively.

Pre-industrial-scale ceramic tile productionThe pre-industrial-scale production of the recycled ceramic tile was undertaken by a ceramic tile manufacturer located in Castellón, Spain. The composition 55CDW was selected for the production tests. Pieces of 30cm×60cm×0.9cm were uniaxially pressed at 320kg/cm2 and glazed. They were dried for 90min to adjust the humidity from 6wt% to 0.5wt%. The glazing and decoration steps were done using conventional glazes by waterfall glazing and designs by ink-jet printing. The firing temperature was optimised exploring the range from 1100 to 1150°C in a rapid cycle of 39min in total. Two temperatures in the top and bottom sides of the kiln were set, designed as Ttop/Tbottom along the document. The thermal rapid cycle followed is shown in Fig. 3 by the blue colour to serve as an example, differing in duration from the laboratory discrete furnace. The difference in length between the cycles is based on the different setups. While in the laboratory, the furnace must be heated from room temperature; the industrial kiln is a continuous setup where the temperature is stable and controlled, therefore, it can achieve faster heating and cooling ramps. The sintered tiles were tested in terms of linear shrinkage, water absorption, and flexural strength. Finally, they were packed and stored for commercialisation and installation in an actual building.

Results and discussionMaterial characterisation and composition designThe waste characterisation started with a first qualitative inspection of each of the three aliquots of the FIBCs (left, right and top). In SI1, a photograph of each of the aliquots obtained from the collected FIBCs is presented. Waste CER is composed of ceramic tiles with a predominance of red-body ceramics. On the other hand, MIX waste is mainly composed of ceramics and concrete-based material (tile, brick, mortar, concrete, etc.). The presence of foreign materials is also detected in the MIX waste. These are: polymer material (MIX2T), wood (MIX3R), or rests of vegetation (MIX1L, MIX4L), which were considered not representative and not removed for the grinding process. After milling, due to the difference in density and size, they were removed in the sieving step. The XRF analysis of each of the aliquots was carried out separately (Table SI1), and its average (x) and standard deviation (σ) are shown in Table 1 by residue type. The composition found for residue CER corresponds to a standard composition of ceramic tiles [33,34] where SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, and K2O predominate. These elements come from the virgin materials used to manufacture a ceramic tile: sand (SiO2), feldspars ((K,Na,Ca)(Si,Al)4O8) and clays (kaolin, montmorillonite, etc.) with a low loss of ignition due to the high-temperature process followed for their manufacture. This waste is of special interest based on the wide experience that supports using ceramic industry waste to produce ceramic tiles (i.e. same chemical composition) [35,36]. However, this practice is limited to industrial ceramic waste, where the composition is known, stable, and controlled, redirecting the industrial waste into the same production chain [10]. Nevertheless, no information exists about the use of ceramic waste from different suppliers or sources for its valorisation into secondary raw material for new ceramic tile production. On the other hand, XRF analysis of MIX waste reveals a high presence of CaO, which could be directly related mainly to the C–S–H gels, carbonates, and portlandite normally present in concrete-based materials in concordance with a higher loss of ignition (18%) [37]. Carbonates are part of ceramic tile composition (∼10–15wt% of limestone) [33]. This material is employed to control linear shrinkage, having a great influence on the correct rapport between the glaze and the ceramic body [38]. These carbonates have been studied to be substituted by recycled sources such as marble or stone industry by-products [39–41] and eggshells [42]. Nevertheless, to the best of the authors, the use of concrete-type materials has not been studied to date for this purpose. Therefore, a composition containing these two types of materials in a controlled way could be feasible based on the chemical composition and wide experience and literature recycling similar materials to produce ceramic tiles. In this work, to limit the CaCO3-bearing materials content up to ∼10wt%, their content in the MIX waste is overestimated to 90wt%. Therefore, the composition design was as follows: 89wt% waste CER and 11wt% MIX waste. This mixture, without any virgin material, corresponds to 100CDW. To this ratio, 30 and 45wt% of kaolinitic clay were added in the wet milling step, resulting in 70CDW and 55CDW compositions, respectively. The XRF analysis of the produced compositions and the used clay is shown in SI2.

Average chemical composition and standard deviation of residues CER and MIX in terms of equivalent oxide obtained by XRF analysis.

| Na2O | K2O | SiO2 | Al2O3 | MgO | Fe2O3 | CaO | TiO2 | P2O5 | MnO | SO3 | ZnO | L.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| xCER | 0.75 | 3.56 | 63.92 | 16.75 | 1.81 | 5.02 | 5.34 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| σCER | 0.32 | 0.14 | 1.03 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.5 |

| xMIX | 0.90 | 1.73 | 40.61 | 10.23 | 2.81 | 2.73 | 21.79 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.20 | 18.0 |

| σMIX | 0.56 | 0.63 | 9.85 | 2.83 | 1.36 | 0.75 | 7.34 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 7.0 |

The material comminuting resulted in a particle size distribution of d50=4μm and d90=15μm for waste type CER and d50=3μm and d90=12μm for MIX waste. This slight difference is mainly due to the ceramic nature of waste CER in comparison with the predominance of non-ceramic materials such as concrete in waste MIX. The ceramic material is harder than concrete (1.5 vs 0.6MPam1/2 of fracture toughness [43,44]), which difficult its grinding process. These materials’ natures are also reflected in the wear of the milling balls, calculated after 12h of milling each type of waste. For CER residue, a wear rate of 4.0% was obtained, while 2.8% was observed for MIX residue, in concordance with the hardness of each mentioned material.

Milling and spray dryingAfter the two-step milling process, the 70CDW and 100CDW compositions exhibited a 60μm sieving rejection of <0.3wt%, which is in line with the technical requirement for ceramic tile production. The particle size analysis by laser technique revealed an average size of particles to be d50=6μm and d90=22μm for both compositions (Fig. 4b and e), which is lower than the standard pre-industrial compositions (d50 ranged from 8 to 12μm). However, the optical microscope micrographs for the spray-dried granules shown in Fig. 4a and b, respectively, show a larger particle size distribution. The particle analysis of the spray-dried granules shown in the figure resulted in the size of d50=87μm and d90=220μm for 100CDW and d50=75μm and d90=170μm for 70CDW (Fig. 4c and f), while standard granules have a main size of 300–400μm. This sharp difference in size may be due to the processing capacity of 500–600kg/h of the employed pilot spray-drying machine (standard porcelain stoneware (STD) granule comparison in SI3 produced in an industrial spray-dryer of 2TM/h capacity).

Moreover, compositions based on MIX debris needed more water content due to poor slip rheological behaviour during milling, despite the use of sodium tripolyphosphate, explaining the smaller granules. The rheological behaviour of the slip is one of the expected bottlenecks in waste recycling. Soluble salts from mortar, glues, concrete, and similar materials are known for their influence on the increase of viscosity and thixotropy of the slip. In the present study, this challenge was only assessed by the addition of clay, deflocculant, and a higher quantity of water in comparison with standard conditions. However, due to the observed relevance of this parameter, a further study must be conducted in this regard.

A positive impact of the presence of clay on granule homogeneity was observed in 70CDW. Granules appeared to be more spherical, which is critical for ensuring the proper fluidity of spray-dried powder (i.e. material flow in the industrial pipes and hoppers and loading of the press). Further enhancements of the new tile's spray-dried powder properties will force optimising the wet milling efficiency by decreasing the grinding time and improving the spray drying to obtain larger granules in size.

The characterisation of the three spray-dried compositions in an pre-industrial environment was evaluated. In Fig. 5, different operational parameters of the spray-dried compositions are presented. First, all tested parameters decrease in quality terms with the increase of CDW content. Regarding the flowability of the spray-dried compositions (Fig. 5a), CDW100 and CDW70 showed lower values in comparison with the STD. Poor flowability constitutes a significant limitation as it may cause the material stuck in storage silos, feed pipes, and hoppers, resulting in several issues in the pressing process, too, directly affecting the properties of green tiles, particularly their bulk density and mechanical strength [45] what makes the composition industrially unworkable for the pressing process. Therefore, due to the rheological problems, the 100CDW composition is discarded for further industrial application. Both the apparent density of the atomised powder and of the pressed unfired compact are negatively affected by the presence of CDW in the composition. These differences could be related to the smaller granule size, lower plasticity of the materials, and smaller average particle size discussed before. There is no established threshold to be fulfilled in terms of density; nevertheless, it has a direct impact on derived properties such as flexural strength (Fig. 5d) and flowability (Fig. 5a). These parameters represent significant issues for industrial applications. As can be observed, both properties are below the standard, being those in unacceptable values for 100CDW composition. Finally, it is worth noting that the spray-dried composition 55CDW presents values comparable to the “STD”, porcelain stoneware tile composition, which is the top-quality product available in the market, proving the adequacy of a high-content CDW composition for industrial scaling in terms of spray-dry properties.

Spray-dried powder characterisation of 100CDW, 70CDW, and 55CDW in comparison with standard porcelain stoneware tile material (STD) in terms of (a) flowability, (b) apparent density of the spray-dried granules, (c) apparent density of the unfired compact, and (d) flexural strength of the unfired compact.

Before scaling up to a pre-industrial level, the following validation tests were performed to identify potential problems in the further processing steps of the compositions (pressing and firing). Thermal characterisation addressed by dilatometry analysis is shown in Fig. 6. Both compositions have a similar behaviour in the range of 25–900°C, when they start to sinter as indicated by the samples’ slight shrinkage. From 1200°C, the softening and therefore deformation of the samples can be observed. Finally, the specimen expansion (sphere formation) due to the material melting is shown at 1250–1290°C, which experiences higher values for 70CDW composition. The specimen 100CDW experiments these transformations at lower temperatures in comparison with 70CDW, probably due to the higher presence of CDW at the detriment of clay content. This could be explained by the carbonate content of the CDW (most likely in cement-based materials), which contributes to the decrease of the firing temperature in ceramic tiles [46]. Based on this, the chosen temperatures for the firing test ranged from 1115 to 1155°C for the 70CDW composition, to avoid the sample deformation.

Fig. 7a shows a photograph of 3cm×8cm samples: pressed compact and after firing at 1115, 1135, and 1155°C (from left to right, respectively). For those specimens, density, linear shrinkage, mass loss, water absorption, and flexural strength were addressed and are presented in Fig. 7b. The properties of those samples fired up to 1135°C remain stable and in good acceptance values, probing the viability of the specimen firing in this temperature range, except for linear shrinkage. This latter parameter is comparably higher than a standard ceramic tile shrinkage (∼5–7%), which is important to control the final aspect of the ceramic tile and the dimensional stability. At 1155°C, the specimens undergo pyroplastic deformation. The pyroplastic behaviour might depend on the low particle size, the glassy phase of the clay-based ceramic used as waste, and the fluxing agent content, such as calcite or dolomite [46].

The 70CDW composition was pressed at 420kg/cm2 in 50cm×50cm×0.9cm tiles for a preliminary firing test in the industrial kiln. Two common thermal cycles were tested, long (69min) and short (46min) red body tile industrial cycles, with a dwell temperature of 1155 and 1145°C, respectively. Pyroplastic deformation problems were observed in both cycles (Fig. 8a–c), being these improved in the short cycle. The sample bending in the case of a long cycle (Fig. 8a) and their cracking for a short cycle (Fig. 8b and c) were inadequate for ceramic tile requirements. These deformations highlight the need for composition optimisation as well as an adaptation of the firing temperature. Therefore, the virgin clay was adjusted up to 45wt%, resulting in the 55CDW composition for further tests. Spray-dried granules of the 55CDW composition showed similar values to the 70CDW in terms of particle size and spray-dried granule size due to using the same spray drier. However, 55CDW presents a high apparent density of the granules, Fig. 5b, which also contributes to the flowability.

The 55CDW composition was tested in different thermal cycles, reducing temperature: 1100–1150°C (Fig. 8d) with two cycles, 39 and 44min long. The tests were performed on industrial-size tiles, 60cm×30cm×0.9cm in size. The temperature increase resulted in the pieces’ dark colouration in addition to larger shrinkage, which will be responsible for the possible increase in density and decrease in water absorption values, presented below. However, based on a qualitative evaluation of the resulting specimens, the lowest temperature cycle was chosen as the optimal thermal cycle (1110/1110°C, 39min long), since all the tested cycles resulted in comparable results with no significant mechanical losses, together with the lowest temperature requirement.

Ceramic tile production at pre-industrial scaleComposition 55CDW was selected for pre-industrial production of novel recycled ceramic tiles, following a fast firing at 1110°C. A conventional procedure for ceramic tiles was followed in ceramic tile manufacturing facilities. Photographs of each pre-industrial step are presented in SI3. In Fig. 9a, the final properties of the produced novel recycled ceramic tile in terms of water absorption and flexural strength are shown. They are presented in comparison with the standard for: porcelain stoneware (BIa) red firing stoneware (BIb), red-firing stoneware wall tile (BIIb) and “monoporosa” or “birapida” wall tiles (BIII) (based on ISO 13006:2018). The achieved water absorption value lies in the ceramic wall tile threshold (class BIII). However, recycled ceramic tiles have advantages over wall tiles, such as considerably higher flexural strength comparable to stoneware floor tiles, top-quality material (class BIa), and maintaining a low weight-to-volume. This latter parameter is important for the final application in walls, where a low weight will ensure proper performance.

(a) Final characteristics of recycled ceramic tiles compared with BIa (porcelain stoneware floor tile), BIb (stoneware floor tiles), BIIb (red firing stoneware and wall tiles), and BIII (Monoporosa or Birapida wall tiles) in terms of water absorption, flexural strength, and classification type based on ISO 13006:2018. (b) Recycled ceramic tiles containing 55wt% of CDW and (c) Final aspect of the recycled ceramic tiles’ installation performed in an actual building.

Regarding the needed temperature, recycled ceramics require a slightly lower temperature for sintering using a short sintering cycle, which means a reduction of energy that, combined with the high percentage of recycled material used, makes these new tiles a more sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative. Therefore, it was demonstrated that the feasible manufacturing of recycled ceramic tiles containing 55wt% of CDW not used to date for this purpose by reducing sintering temperature. Moreover, the recycled composition is suitable for industry, and it is adapted to the current production lines. A picture of the finally developed recycled ceramic tiles is presented in Fig. 9a along with their installation in a real building (Fig. 9b).

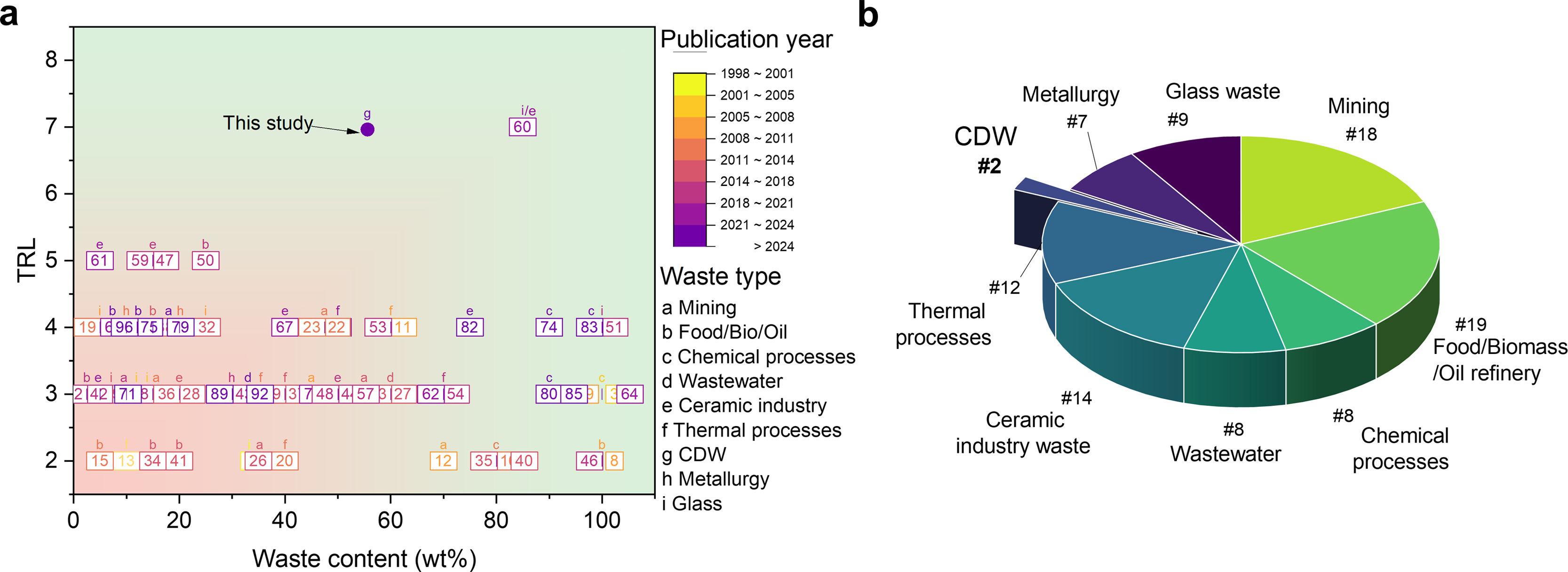

Scientific-technical, environmental, and economic impactTechnical and scientific impactCeramic tiles have been considered for the implementation of circular strategies, including a wide variety of waste in different proportions. Based on the recent and complete revision of Zanelli et al. about the literature on recycling ceramic tiles, this information has been updated and presented as follows. In Fig. 10a, the distribution of recent scientific publications is sorted by Technology Readiness Level (TRL, (y-axis), and waste content in percentage (x-axis). Moreover, a letter above each point in the graph designing the waste type or provenance as: “a” mining, quarrying and mineral treatment; “b” food waste, biomass combustion plants and oil refining waste; “c” Inorganic chemical processes; “d” wastewater treatment; “e” ceramic industry; “f” thermal processes; “g” construction and demolition waste; “h” metallurgy; and “i” glass waste. The distribution in the number of publications by waste type is shown in Fig. 10b. The year of publication is also indicated by colour, following the legend shown at the right-hand side. For the sake of simplicity, only studies regarding the production of ceramic tiles and standard procedures (i.e., imitating industrial procedure, avoiding alternative routes such as alkali activation, geopolymerization, etc.) published after 1998 are presented. TRL-level guidelines were used for this sorting study, and the list of the 97 gathered publications, as well as publication details, is shown in Supplementary Information. First, it is noted that the tendency of publication relies on low waste content or low TRLs stages, showing the difficulty of obtaining tiles with a high content of waste pre-industrially. This trend makes the accumulation of publications in the TRL 3–4 with less than 50wt% of waste content. Regarding the year of publication, the oldest publications are typically related to the low TRL stage; however, there is no specific trend regarding the waste content since high values can be found in the early years. This tendency causes an intangible barrier difficult to overcome when trying to reach the ideal case: high waste content in a developed TRL stage. Regarding this last case, only one publication can be found concerning the recycling of pre- and post-consumer glass waste [47]. In this publication, the authors report an industrial production using 85wt% comprising a blend of scrap packaging glass from urban separated collection (post-consumer waste) and industrial ceramic waste (pre-consumer waste), probing the industrial viability of high-waste content stoneware tiles.

On the other hand, waste type is also indicative of the research trends. The breakdown of the number of publications by type of waste is shown in Fig. 10b. The most explored waste types are mining, chemical inorganic processes subproducts, and ceramic industry waste. These types of waste are, in general terms, known and chemically stable, which constitute a reliable source of materials. In contrast, CDW is the least explored type of application, with only 2 remarkable publications available in the literature considering real CDW in a pre-industrial environment of ceramic tile manufacturing. Vidoni et al., 2007 reported the viability of a high content of CDW (100wt%); however, this publication remains at a low TRL level, and they report that alkaline-earth cations are preferentially leached even though the sintered ceramics have a high level of densification. Acchar et al., 2013 explored the production introduction of 20wt% of CDW, highlighting the possibility of tailoring the inert or fluxing behaviour of the final composition by varying the different CDW content, concluding in positive results regarding the debris incorporation. Despite these promising results for CDW, the present study is the first publication that explores the pre-industrial production of 55wt% CDW recycled ceramic tiles, demonstrating the technological viability of the product. However, it is important to highlight that further scientific evidence is needed for process optimisation, as well as the need for an automatic and cost-effective sorting technology that can offer a reliable source of highly pure waste to the industry.

In addition to the high impact of this work on the state of the art, as previously mentioned, the implementation of the proposed recycled ceramic tile has a positive environmental and economic impact compared with standard procedures followed in the ceramic industry. Three main points are regarded below for the assessment of this impact: (i) Transportation optimisation, (ii) valorisation of waste material over virgin raw material, and (iii) Temperature reduction.

Waste valorisation over virgin raw materialBesides the benefit that the proximity-product consumption means, the waste valorisation implies an important added benefit to regard. In Spain, approximately 35hm3 of CDW are produced yearly [21]. Considering that the Spanish ceramic industry produced 7 Mt of ceramic tiles in the last 2023 [48], it would take about 10 years to consume the national CDW yearly production in the manufacture of the novel recycled ceramic tile (55wt% of waste content). The estimated cost for the virgin raw material typically employed for ceramic tile production is 1.29–1.81€/m2. In the case of CDW, the price is estimated at 0.55€/m2[28]. Considering a product that substitutes 55% of the virgin material with this waste, a reduction in the cost of ∼32–40% raw material is expected when the proposed circular approach is adopted. Moreover, the environmental benefit of recycled ceramic tile is a reduction of the impact on mining and mineral treatment processes.

Improving sustainability in high-energy-demand processesTwo aspects are relevant to be considered from the point of view of sustainability related to the high demand for energy in the ceramic tile processing: the raw material transportation and the thermal treatment at high temperature.

Ceramic tiles are composed of feldspar, clay, and sand. In Spain, raw materials for ceramic tile production are imported primarily from Ukraine and Turkey, besides national consumption. Spain imported $186M of feldspars in 2022, 72% from Turkey [48]. This importation represents a significant percentage of the raw material cost, besides the greenhouse gas emissions derived from long-distance transportation. Considering the ocean-going freighter transportation from Turkey to Spain (regarding approximate values of 18 knots, 3.5 days, 225l/h, 1€/l), it would cost c.a. 18487€ to import an average of 40.000 TM of feldspars, only considering the marine fuel cost. This trip would emit approximately 1820 TM of CO2 into the atmosphere. In this perspective, the recycled ceramic product here proposed only considers 45% of virgin clay, avoiding the use of feldspars and therefore, their import. Moreover, 55% of the composition is from CDW, which also contributes to reducing the environmental impact. This waste comes from nearby waste management facilities in the production plant, which makes the transportation and therefore the associated CO2 emission almost negligible by comparison to the process.

Process energy reductionThe high-temperature sintering process is among the most energy-intensive stages in ceramic tile manufacturing (i.e. 55% of the energy breakdown consumption) [49]. This process is typically done at 1155–1200°C and can vary depending on the ceramic product. The differences in energy consumption during industrial thermal treatment in the same manufacturing plant ranged between 15.44kWh/m2 for wall tile (BIII) and 20.04kWh/m2 for stoneware floor tile (BIa) [50]. Considering that the thermal energy comprises both the drying process (18% of the total) and the sintering process (82% of the total), the reduction in maximum sintering temperature between both classes of ceramic tiles is 3.8kWh/m2. The proposed recycled ceramic tile is sintered at 1110°C, which means a reduction of 45°C compared to the sintering of wall tile (BIII) and 90°C compared to the sintering of stoneware floor tile (BIa). Thus, the sintering temperature reduction of 45–90°C observed for the recycled ceramic tiles against standard BIII and BIa tiles would imply an additional reduction in thermal energy consumption. Because there is not a linear relationship between maximum sintering temperature and energy consumption, a reasonable estimated energy reduction will range between 3 and 7kWh/m2. In the case of CO2 emissions, each kilowatt-hour of electricity consumed produces 0.21kg of CO2 when generated from natural gas [51]. Considering the estimated energy reduction range, a saving of 0.6–1.4kg of CO2 per m2 would be reached. This value range is an indicator of the temperature reduction that the new recycled ceramic tile would represent an incentive for the industry; however, real consumption of the oven in stable working conditions will be required.

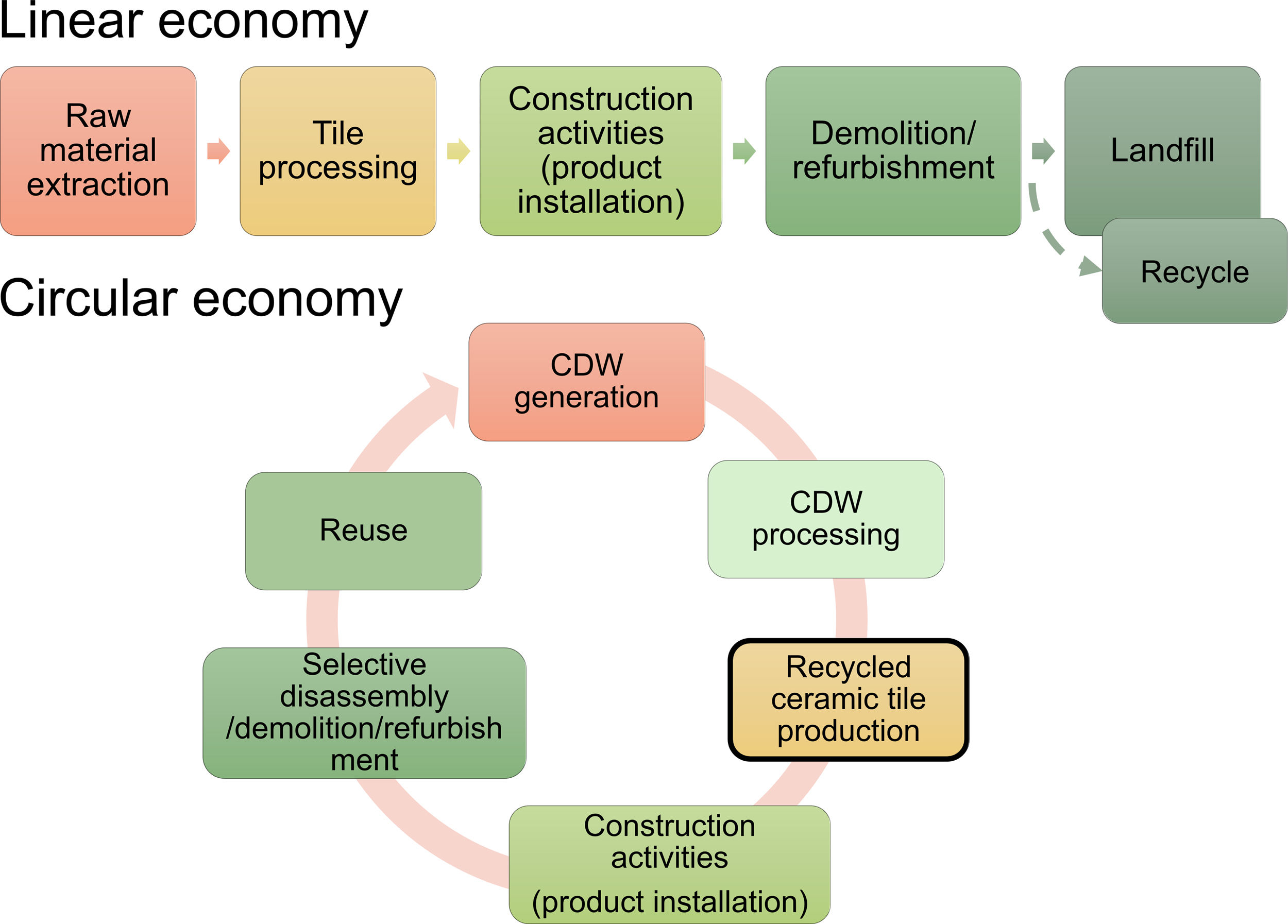

Progress in the adoption of circular processes in the ceramic tile sectorFinally, Fig. 11 shows two economic models in the construction sector. In the first model shown, a linear process is observed, which corresponds to the standard one currently applied. This model begins with the exploitation of virgin natural resources for the manufacture of construction and demolition materials, which are installed in the home irreversibly to begin their useful life. Once this life is over, the buildings are demolished or remodelled indiscriminately, generating the so-called CDW. This waste is finally stored in the environment, constituting the practice known as landfill. To a lesser extent, these materials are recycled in low-added-value applications such as road or slope fill. In contrast, the current work proposes a feasible transition to a circular economy model, shown in the second part of Fig. 11[52]. The target itself is not limited to transforming this waste part of the new construction process, but also to eliminate the practice known as landfill in an ideal scenario. The integration of this waste into circular processes can contribute to lowering natural resource extraction through enhanced recycling. This circular economy promotes the preservation of the environment through the reduction of virgin natural resources exploitation, the reduction in transportation of said materials, or the use of CDW waste through higher value-added processes but also limits the generation of new CDW in the near future thanks to practices known as selective disassembly, getting closer to a sustainable model over time with less environmental impact.

ConclusionsIn this study, the feasibility of obtaining a ceramic tile with the highest CDW content at a pre-industrial level has been explored. The waste used for the study comprises a mixture of mainly ceramic waste (ceramic tiles) and mixed waste enriched in ceramics (mixed CDW). The composition limits the carbonate content to 10%.

The recycled tiles obtained at the pre-industrial level showed properties in line with better quality wall tiles (BI group) in terms of mechanical strength values. The porosity found in these tiles was 12%. These values make the recycled tiles excellent candidates for wall cladding, as they possess high flexural strength while maintaining a low volume-to-weight ratio due to their high porosity.

Therefore, this study opens the possibility of exploring the incorporation of construction and demolition waste into the ceramic industry, giving a second life to this waste, which has been downcycled to date. Moreover, the novel-designed ceramics require a lower temperature for sintering, which is nearly 7.5% lower in a short sintering cycle. It can be concluded that the manufacture of novel recycled ceramic tiles with 55% CDW is feasible pre-industrially. Finally, the production of these novel recycled ceramic tiles is evaluated in terms of economic and environmental profitability, highlighting the reduction estimation of 3–7kWh/m2 and 0.6–1.4kg of CO2 emissions per m2 compared to the production of BIII or BIa ceramic tiles, based on the sintering temperature reduction. Moreover, the transportation cost calculation is also reduced due to the nearby location of the waste management plant, compared to the importation of virgin materials from abroad (e.g. Turkey and Ukraine).

However, this first study intends to demonstrate pre-industrial viability; however, it would be necessary to establish standards for the processing of construction and demolition materials, which present great variations depending on the area where they are generated and stored. These variations should be taken into account when considering industrial production. However, it has been observed that having a concise knowledge of the materials, their use for ceramic tiles is feasible in controlled compositions.

On the other hand, another bottleneck process identified is the slip rheology of the waste mixtures while they are being processed (wet milling). In future work, a thorough control of these properties and the use of optimised deflocculant additives could improve suspension stability, even being possible to increase the amount of residue that the mixtures possess to more than 55% of CDW currently tested.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the following projects: European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programs ICEBERG (No. 869336) and ICARUS (No. 101138646), and AFICHES from CSIC (PIE 20460E101). The authors also acknowledge José Manuel Baraibar Díez from Viuda de Sainz S.L. for the installation of the tiles demo case and the 9c photograph.