One of the composites with exceptional mechanical, thermal, and oxidation resistance properties is ZrB2–SiC. In this research, we produced the ZrB2–SiC composite with Si3N4 additive (1–2–3 and 4% by volume) in the base composition through sintering without applying pressure. The evaluations included microstructure analysis using a FE-SEM and oxidation properties in an oxyacetylene test chamber under oxygen and C2H4 gas exposure. The results demonstrated that as Si3N4 content increased, the structure became more homogeneous in granulation, with fine and uniform grain formation promoting composite compaction. The oxyacetylene test results showed enhanced oxidation resistance in samples with higher Si3N4 amounts, particularly in the 67vol% ZrB2–10%ZrC–20%SiC–3%Si3N4 sample, which had the lowest mass erosion rate.

Uno de los compuestos con propiedades mecánicas, térmicas y de resistencia a la oxidación excepcionales es el ZrB2–SiC. En esta investigación, se produjo el compuesto ZrB2–SiC con aditivo de Si3N4 (1, 2, 3 y 4% en volumen) en la composición base, mediante sinterización sin aplicación de presión. Las evaluaciones incluyeron el análisis de la microestructura mediante un microscopio electrónico de barrido de emisión de campo (FE–SEM) y el estudio de las propiedades de oxidación en una cámara de prueba con oxiacetileno bajo exposición a gases O2 y C2H4. Los resultados demostraron que, a medida que aumentaba el contenido de Si3N4, la estructura se volvía más homogénea en la granulometría, con la formación de granos finos y uniformes que favorecieron la compactación del compuesto. Las pruebas con oxiacetileno mostraron una mayor resistencia a la oxidación en las muestras con mayores cantidades de Si3N4, particularmente en la muestra con 67% Vol ZrB2–10% ZrC–20% SiC–3% Si3N4, la cual presentó la menor tasa de erosión másica.

Ceramics composed of ZrB2 with a secondary phase like ZrC and SiC exhibit superior compaction behavior and material properties compared to single-component and integrated ceramics [1,2]. The composite approach is employed to enhance the oxidation and erosion resistance of single-phase ceramics. For instance, incorporating a second phase such as ZrC, Si3N4, or HfB2 results in a composite with increased strength, better oxidation, thermal shock resistance, and erosion protection [3,4].

Bahararjmand et al. [5] investigate the impact of Si3N4 content on the hardness and microstructural development of ZrB2–SiC material. Key findings include: BN phase formation at SiC–ZrB2 interface due to B2O3 and Si3N4 reaction; increased Si3N4 amount leads to more in situ BN; despite h-BN being soft, its presence in ZrB2–SiC composite improves hardness through increased relative density; the Vickers hardness of ZrB2–SiC ceramic is around 17GPa, which rises to 20GPa with 4.5wt% Si3N4 addition.

Ultra-high-temperature ceramics are garner growing attention and interest due to their potential use in reusable thermal shielding systems. Innovative hypersonic vehicle designs incorporate sharp airfoils, such as nose caps, engine intakes, and leading edges, to enhance aerodynamic performance. These components are consistently exposed to severe environments, including oxidizing atmospheres, high speeds and pressures, and temperatures ranging from 1500 to 2400°C [6,7].

In the study of Hao et al. [8], Al2O3 and Si additives were incorporated into ZrB2–20vol% SiC ceramic mixtures, and ZSA (ZrB2–SiC–Al2O3) and ZSS (ZrB2–SiC–Si) coatings were prepared on C/C composites using atmospheric plasma spraying. Both coatings exhibited dense structures after 1200°C oxidation. However, ZSA had large cracks and no glassy phase, leading to poor oxidation resistance. In contrast, ZSS had a borosilicate glass phase that sealed pores and cracks, providing stable weight gain during oxidation. At 1500°C, ZSA formed a glassy phase and showed improved oxidation resistance, while ZSS had large pores due to rapid B2O3 volatilization, reducing its oxidation resistance. Adding Si promotes glassy phase formation at lower temperatures (1200°C), and adding Al2O3 reduces glassy phase viscosity, effectively sealing cracks and voids at higher temperatures (1500°C).

Vedel et al. [9] studied the effect of adding 5vol% Mo2C on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and oxidation behavior of ZrB2–15vol% SiC ceramics. Ceramics are made using simple hot pressing or a two-stage process of vacuum treatment followed by hot pressing at 1600°C. During the sintering process, Mo2C materials are in (Zr, Mo) B2, (Zr, Mo) C and (Mo, Zr) B phases. Both methods produce dense materials; the two-stage method has larger grain size and higher (Mo, Zr) B phase content. Hot-pressed material has the highest strength at room temperature (821MPa) due to its small size. Its strength is 150–180MPa due to grain boundary softening at 1800°C in vacuum and the ductility of the (Mo, Zr) B phase. The strength of Mo2C does not increase at low temperatures. In a 2-h oxidation test at 1600°C, the addition of Mo2C reduced the oxide thickness by almost fourfold. Borosilicate glass coating covering the zensiraunch structure on the surface with boride and molybdenum oxide count. The powder subjected to vacuum treatment before sintering has a thin oxide layer due to its coarser grain size and higher (Mo, Zr) B phase content, and is still unoxidized as a stable compound.

Zhao et al. [10] examine the oxidation behavior of ZrB2–SiC ceramics with varying porosities, achieved through spark plasma sintering at 1400, 1600, and 1800°C. Oxidation tests were conducted at different temperatures and durations. Key findings are: densities (4.858, 5.030, and 5.245g/cm3) and porosities (11.9%, 8.8%, and 4.9%) in ZrB2–SiC ceramics were influenced by sintering temperatures; After oxidation, the oxide layer had bubbles, voids, and cracks, with surface integrity decreasing with higher temperature and time; porosity played a significant role in oxidation behavior, as the oxide layer thickness and weight change increased with higher porosity, and ceramics with lower porosity had fewer defects.

This study presents an innovative approach to enhancing the properties of ZrB2–SiC composites through the strategic incorporation of Si3N4 additives. Utilizing a pressureless sintering method, we systematically investigated the effects of varying Si3N4 volumes (1–4%) on microstructural uniformity and oxidation resistance. Our findings provide compelling evidence that even minimal additions of Si3N4 can significantly improve the composite's mechanical integrity and environmental durability. The incorporation of an optimal volume fraction of Si3N4 leads to a notable increase in phase homogeneity and a significant reduction in oxidation rates, attributed to the formation of a dense borosilicate glass layer that offers protection against high-temperature degradation. This research not only highlights the critical role of Si3N4 in enhancing composite performance but also establishes a foundation for future investigations in ultra-high-temperature ceramics, where precise management of additives could yield transformative advancements in materials science applications.

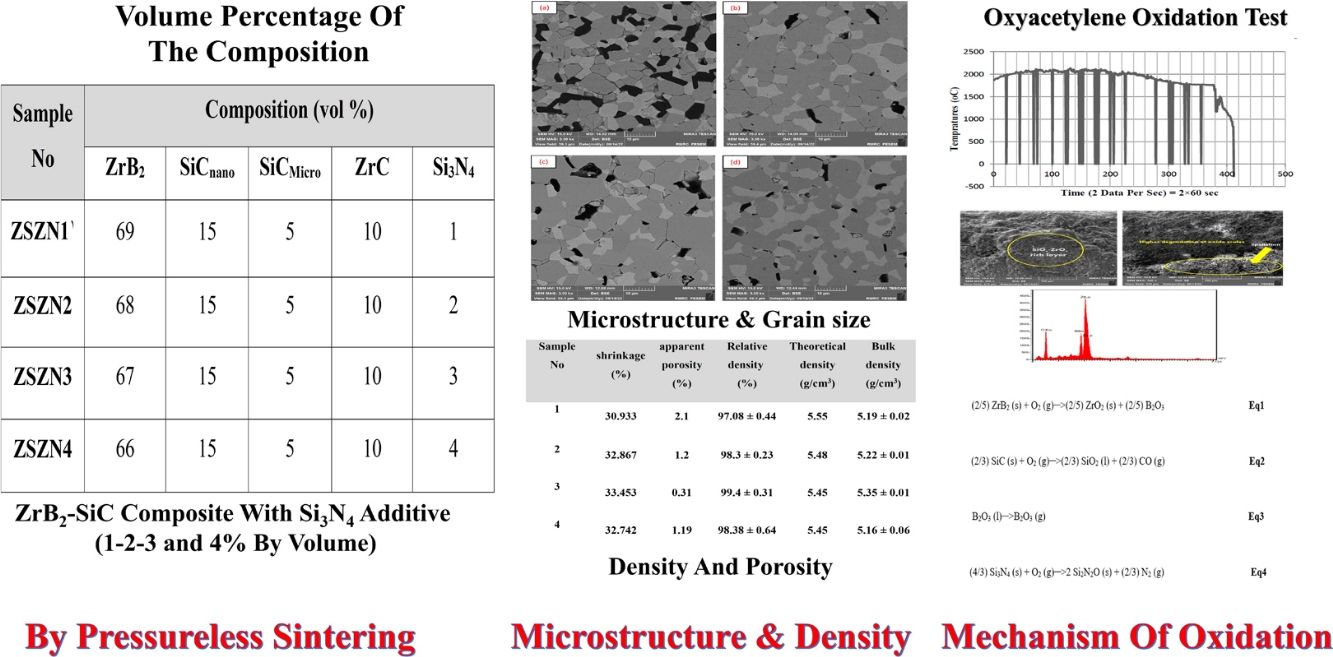

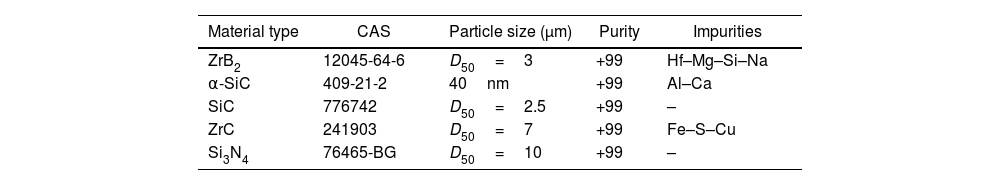

Materials and methodsThe compositions of materials employed in this study for the manufacturing of ZrB2–SiC composites are detailed in Table 1.

In this study, multi-component composite ceramics are fabricated using a variety of base powders, reinforces, sintering aids, and resins. Each raw material possesses specific properties, such as strength, stiffness, toughness, heat resistance, cost, and production speed. However, the final properties of high-temperature composite ceramics produced from these materials are not solely determined by the raw materials’ characteristics but also depend on the design method, application technique, placement within the structure, and manufacturing process. The uniaxial press method was used to create samples for this research. To manufacture composite samples, powders were used as reinforcement and sintering aids alongside resin. The powders of all raw materials, except SiC nano, were using a ball mill with a powder-to-pellet weight ratio of 1:10 and ethanol. Zirconia bullets of various sizes with size dispersion were utilized. Primary powders were milled for 3h at 250rpm. After grinding, the suspension underwent ultrasonication for 10min to prevent agglomerate formation. The milled powders were dried in an oven at 180°C for 4h. The primary powders, weighed separately, were blended according to the specified composition. This mixture was then placed into a steel cup along with zirconia balls, 99% ethanol, and a dispersant. Milling was conducted in a satellite grinder for 1h at a speed of 250rpm. The resultant mixture was subsequently dried and combined with 5% by weight of phenolic resin that had been dissolved in ethanol for the granulation process. The granulated powders are formed into tablets with a diameter of 10mm under a uniaxial pressure of 100MPa. To enhance the initial strength, the samples undergo cold isostatic pressing at a pressure of 2000bar for 5min. Finally, pressureless sintering of the composite samples was conducted at 2150°C under vacuum conditions. The sintering temperature increased from room temperature to 2150°C (heating and cooling rate of 10°C/min). The entire specimen, approximately 4mm thick, is then utilized for the oxidation test.

Determination of shrinkage, apparent porosity, relative density and bulk densityThe linear shrinkage of the samples after sintering was calculated as [(D0−D1)/D0]×100, where D0 and D1 are the diameters of the green and sintered samples, respectively. The bulk density and apparent porosity were measured using the Archimedes method with water immersion, in accordance with ASTM C373-88. Each sample was first dried and weighed in air (Wa), then boiled in water and weighed again while immersed in water (Wi), and finally weighed saturated with water in air (Ws). Bulk density and apparent porosity were calculated using standard equations. The relative density was determined as the ratio of the measured bulk density to the theoretical density, where the theoretical density was calculated based on the rule of mixtures from the densities of the constituent phases. All dimensional measurements, including shrinkage determination, were conducted with equipment capable of a resolution up to three decimal places, and results are reported accordingly.

Microstructure evaluationTo examine the microstructure, suitable samples were molded using a hot mount, and the cross-section of the samples was polished. This process was carried out by a polishing machine operating at 200rpm. The polishing of the samples involved three stages: initial, middle, and final. In the initial stage, diamond grinding discs with grades of 120, 220, and 600μm were used for 15min each. In the middle stage, silicon carbide sandpaper with mesh sizes of 80–2500 was employed. The final polishing of the samples was done using felt, wet, and water. After polishing, the samples were etched with a HF:HNO3:H2O solution in a 1:1:3 ratio for 20s.

Microstructural characterization and phase analysis were carried out using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; MIRA 3, TESCAN, Czech Republic). The instrument was operated at an accelerating voltage of 15kV with a beam current of 1.5nA. The system is equipped with a high-resolution in-lens detector for secondary electron (SE) imaging as well as a backscattered electron (BSE) detector. The typical spatial resolution is up to 1.2nm at 30kV. Elemental analysis and mapping were performed using an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector (Oxford Instruments, UK) attached to the FE-SEM. All micrographs were obtained under high vacuum conditions. Prior to SEM observation, the samples were cleaned ultrasonically in ethanol and, coated with a thin (∼10nm) layer of gold by sputtering. Anix software was utilized to determine the average size of the synthesized powder particles, while Image J software was used to assess the size distribution of the synthesized powder particles.

Oxidation behavior evaluationThe oxidation behavior of the specimen was assessed using an oxyacetylene test, applying temperatures ranging from 2500 to 2600°C for a duration of 120s, with an approximately equal ratio of acetylene to pure oxygen. The distance between the sample and the nozzle tip was maintained at 10mm, and the inner diameter of the nozzle orifice was 2mm. The composition of raw material powder for all the manufactured samples is provided in Table 2.

Volume percentage of the composition of the samples made.

| Sample no. | Composition (vol%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZrB2 | SiCnano | SiCMicro | ZrC | Si3N4 | |

| ZSZN1 | 69 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 1 |

| ZSZN2 | 68 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 2 |

| ZSZN3 | 67 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 3 |

| ZSZN4 | 66 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 4 |

In the coding of the samples, every letter represents an abbreviation of the full name of the respective substance, and the subsequent numbers denote the percentage of the additive involved.

ZSZN=ZrB2+SiC (15vol% nano SiC+5vol% micron SiC)+ZrC+Si3N4.

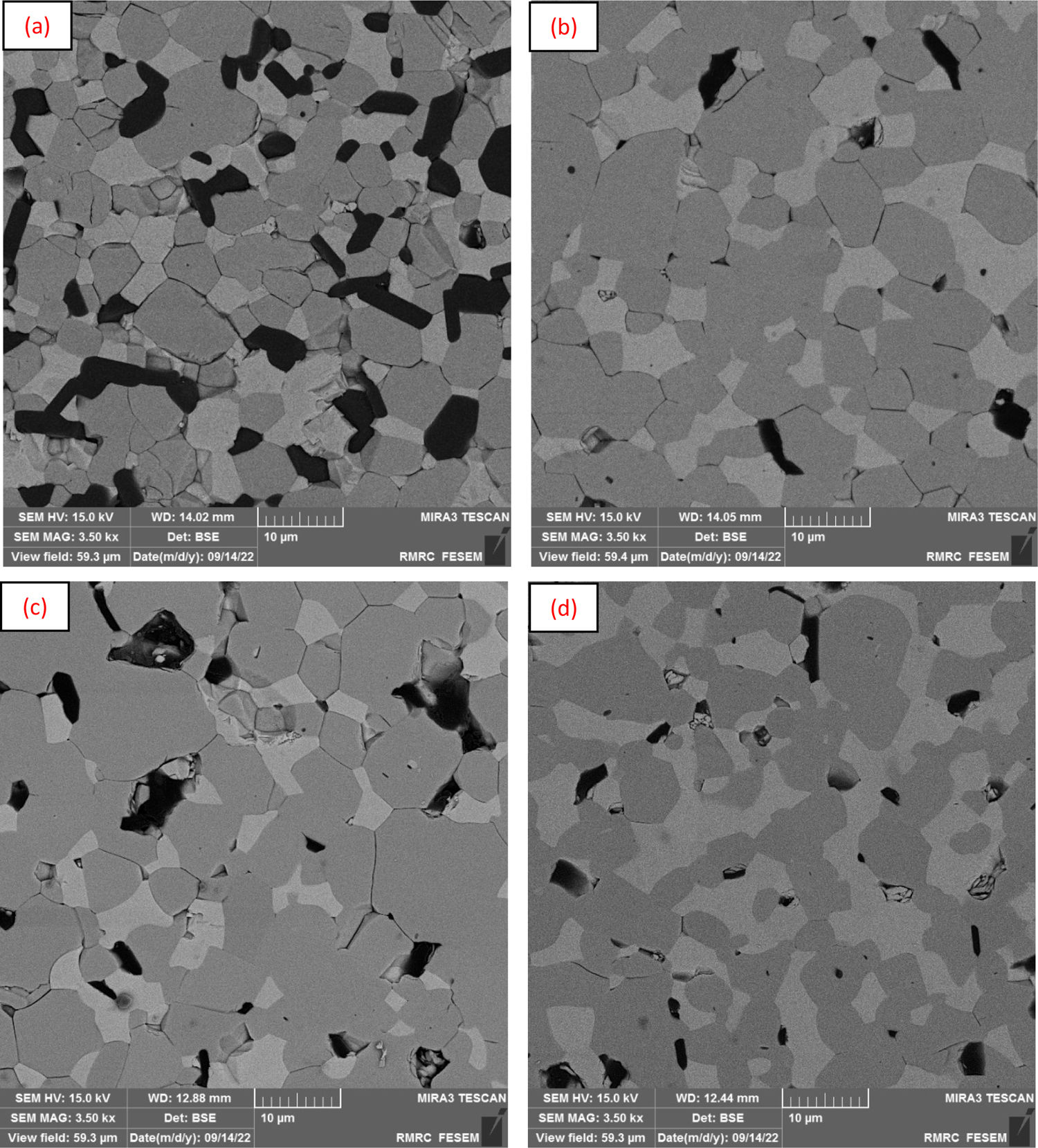

To examine the microstructure and microscopic analysis of the samples, microscopic images were prepared from the sintered specimens. Below, BSE SE images of the 2150°C sintered samples in an argon atmosphere are displayed. In Fig. 1(a)–(d), SE images of the prepared samples are shown. The ZSZN1 sample's microstructure exhibits larger pore dimensions in terms of morphology, with a higher quantity and dispersion within the structure compared to the rest of the samples. This can be attributed to the absence or insufficiency of the the Si3N4 phase, leading to the rapid growth of ZrB2 grains at high temperatures. By incorporating Si3N4 into the composite, the development of background phase grains at high temperatures and the confinement of pores within grain boundaries have been prevented, reducing their quantity. As a result, the increase in density with the presence of Si3N4 phase is natural, and it can be said that with the rise in the volume percentage of Si3N4, the composite becomes denser. According to the findings in previous sections and the existence of an optimal limit for the additive amount of up to 3vol%, this phenomenon is evident in the microscopic images. In the ZSZN4 sample, we observe an increase in porosity again, which can be justified by the density results (Table 5), where the relative density was reduced.

In Fig. 2(a)–(d), FE-SEM images of the samples at a higher magnification are displayed, captured using the BSE method. In the SE imaging technique, all phases appear in the same color, allowing for the identification of cracks and porosity. As seen in Fig. 2(a)–(d), the background of the images is shown in various colors, which can be attributed to the differing densities of the constituent elements. In this image, three phases with dark gray, light gray, and black colors are discernible. According to the studies [11–13], it can be concluded that the light gray color corresponds to the ZrC phase, as it has the highest density among the materials used and appears brighter than the other phases. The dark gray color signifies the ZrB2 phase, and the black color indicates the presence of the SiC phase. Considering that in BSE images, porosities are also displayed in black, these are compared with SE images, which reveal that in the ZSZN1 sample, the structural porosity is high. With the addition of the volume percentage of the additive, this amount of porosity is reduced to the known optimal value. As depicted in parts (c) Figs. 1 and 2, it can be observed that with the increase in the volume percentage of the Si3N4 phase up to 3%, the porosity in the structure decreases.

BSE of the fabricated samples: (a) ZSZN1, (b) ZSZN2, (c) ZSZN3, and (d) ZSZN4 [14].

Additionally, the reduction of grain size is well-defined. As described in the previous sections, this is due to the placement of SiC and Si3N4 particles in the grain boundaries, which prevents grain growth. The images demonstrate a uniform distribution of reinforcement particles in the background phase, which enhances properties. In the images, light phases have darker colors, and heavy phases (in terms of atomic mass and density) have lighter colors, which is a result of better electron reflection from the surface of heavy phases.

Due to the low-density difference between SiC and Si3N4, distinguishing these two phases in the images is difficult. To address this, EDS was employed for a more detailed investigation and to identify the formed phases, examined below.

As stated, with the increase of Si3N4, the porosity decreases, and the density increases, as well as the structure becomes more homogeneous in terms of granulation. The formation of fine and homogeneous grains drives the compaction of the composite. In Table 3, the average grain size in the samples, obtained using the software (Image j), can be seen, and their microscopic images are also shown in Fig. 3(a)–(d). The average size of the particles in the sample containing 3% by volume of additive is lower than the rest of the samples. This is justified by the results of density and porosity and microscopic investigations. In fact, in the ZSZN3 sample, due to the uniform distribution of elements in this composite, the Si3N4 and SiC phases have prevented the growth of grains due to their location in the grain boundaries, as obtained through the investigations and studies conducted in the sources [15].

Additionally, the formation of a new BN phase at the interface of ZrB2/Si3N4 and the presence of the ZrC phase by preventing the growth of the grains of the ZrB2 background phase and preventing the trapping of pores between the grains improves the sintering behavior, reduces the porosity, and thus increases the sample density to the highest value among other examples, as mentioned in Refs. [16–18]. Based on the investigations done and optimally considering the ZSZN3 sample according to its characteristics, EDS was taken from this sample.

In Fig. 4(a)–(d), the FE-SEM image along with EDS analysis of the ZSZN3 sample is provided. The presence of secondary phases in the microstructure is due to the introduction of grain boundary phases. These grain boundary phases can have a lower melting point and provide a path for oxygen to penetrate into the material. Consequently, they have a destructive effect on the high-temperature capabilities of the material.

The presence of oxygen impurities is detrimental to the compaction of primary powders and causes rapid growth of seeds. Since light elements such as carbon, boron, and nitrogen are not very identifiable in EDS analysis, and there is always some error in quantitative analysis, the presence of these substances in small and limited amounts cannot be relied upon with much confidence and always has some mistake. It is noteworthy that the identification of the BN phase in the composite structure was well-established in similar studies [19,20].

Additionally, the black parts are related to the presence of SiC and Si3N4 phases, which are difficult to identify due to the slight density difference.

To compare and examine the samples more closely, detecting, and identifying dark spots in the microscopic images, the SE and BSE images of the samples are provided at a specific magnification. This allows for the clear differentiation of pores and cavities created from low-density phases. These images can be seen from Figs. 5–8(a) and (b).

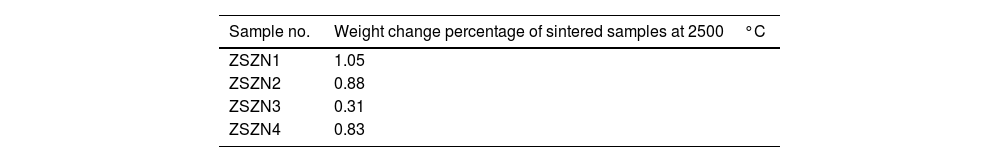

Investigation of oxidation behavior of ZrB2–SiC–ZrC compositeTo investigate the thermal behavior of the samples, an oxyacetylene test or flame test was conducted. The purpose of this test was to examine the oxidation behavior of the ZrB2–ZrC–SiC composite created in the study. For this, the oxyacetylene test was employed, with a temperature of 2500°C applied for 120s. The resulting temperature–time diagram from this test can be seen in Fig. 9. After the samples were exposed to the flame, some carbon was formed on their surface due to the combustion of oxyacetylene gas in the presence of oxygen.

To investigate the microstructure of the composite samples made with the mentioned compounds after exposure to oxyacetylene, microscopic images were taken and are provided in Fig. 10(a)–(d). In these images, the brighter particles are related to ZrO2 due to its high density. This is most evident among the composite oxides, as SiO2 and Si3N4 are difficult to distinguish due to their lower density compared to the background. At lower temperatures (approximately 1100°C), B2O3 oxide can also be observed. However, at the working temperature of this experiment (above 2000°C), the evaporation rate of B2O3 is higher than its formation rate, resulting in it being an integrated oxide [21–23].

In Fig. 11(a)–(c), the images of the oxide surface for both ZSZN2 and ZSZN3 samples, and also the EDS results of the ZSZN3 sample are displayed. The sample surface has been destroyed due to oxidation and the scaling of the sample surface. The ZSZN3 sample, containing 3% by volume of Si3N4, exhibits lesser oxidation. This is attributed to forming a thick layer of ZrO2 and SiO2 oxide phases. According to the explanations provided, the mass increase in the samples during the oxidation process can be credited to the formation of ZrO2 and SiO2. In contrast, the mass decrease can be attributed to the exit of B2O3 and CO gases from the structure.

Oxidation occurs in two fields: linear (change in length) and weight (weight change). By measuring one of these two parameters, one can study the behavior and extent of oxidation. The more significant the change in the mass, the more oxidation occurs. These changes are attributed to forming oxide materials with different densities from the composite's constituent materials. In Table 4, the weight changes of ZrB2–SiC–ZrC composite samples containing various amounts of Si3N4 additives are presented. The ZSZN3 sample, which demonstrated favorable results in terms of physical and mechanical properties, exhibits the highest oxidation resistance among the ZrB2–SiC–ZrC composite samples. This lower weight change compared to other samples supports the results obtained through EDS analysis. The samples ZSZN1 and ZSZN2 have undergone the most significant oxidation, due to the high amount of ZrO2 present in these samples.

The primary reactions [24] in the ZrB2–ZrC–SiC–Si3N4 composite during the oxidation process involve the oxidation of ZrB2 as per Eq. (1), SiC oxidation as per Eq. (2), and B2O3 evaporation as per Eq. (3). The evaporation of B2O3 results in the formation of porosity within the structure, which is later filled by SiO2 generated through SiC oxidation. Moreover, Si3N4 is preferentially oxidized first, following Eq. (4).

Research has shown that with Si3N4 oxidation, two oxide layers, including SiO2 and Si2N2O, can form in the ZrB2–SiC–Si3N4 composite [24]. However, it should be noted that the oxide phase of SiO2 is thermodynamically more stable.

As the structure's density increases, oxygen penetration is more effectively prevented. When comparing samples containing additives, it has been observed that up to a 3% volume percentage of Si3N4, the weight gain decreases. Form 3% volume onwards, weight gain increases to a lesser extent. This can be attributed to the increase in relative density and decrease in porosity, while in 4% volume and higher, it is due to the decline in relative density and increase in porosity.

Malik et al. [24] concluded that incorporating 5% by weight of Si3N4 into the ZrB2–SiC composite increases the resistance to oxidation by 20–25%, and the weight gain of the samples after the oxidation process is less than that of the ZrB2–SiC composite. Monteverde et al. [25] also found that in the ZrB2–SiC composite containing SiC nanoparticles, the weight gain of the samples after oxidation is less than that of the ZrB2–SiC composite containing SiC particles in micron dimensions.

Thimmappa et al. [19] demonstrated that the ZrB2–20vol% SiC–5vol% Si3N4 composite significantly enhances oxidation resistance. The primary reason for this improvement is forming a thick borosilicate oxide layer on the surface of ZrB2-based composites.

Indeed, the synergistic effect of SiC and Si3N4 contributes to the oxidation resistance of composites. During the oxidation process, a portion of the B2O3 phase evaporates, while the remaining part reacts with SiO2 to form a borosilicate glass layer. This SiO2-rich layer effectively prevents oxygen penetration into the composite structure, thus protecting the sample from oxidation [26].

It is worth noting that denser structures block oxygen penetration better. In Table 5, the shrinkage, density, and porosity of the samples after sintering at 2150°C are given using the Archimedes method. The relative density of the sample increases with the addition of Si3N4. An increase in density and a decrease in porosity in the body can be seen with the addition of Si3N4, which can be proven by the effect of Si3N4 on the sintering behavior of ZrB2-based composites.

The results of density and porosity of ZrB2–ZrC–SiC composites.

| Sample no. | Shrinkage (%) | Apparent porosity (%) | Relative density (%) | Theoretical density (g/cm3) | Bulk density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZSZN1 | 30.933 | 2.102 | 97.086±0.051 | 5.554 | 5.190±0.024 |

| ZSZN2 | 32.867 | 1.206 | 98.297±0.061 | 5.476 | 5.224±0.057 |

| ZSZN3 | 33.453 | 0.310 | 99.378±0.024 | 5.447 | 5.348±0.031 |

| ZSZN4 | 32.742 | 1.196 | 98.381±0.016 | 5.452 | 5.158±0.014 |

In this study, the impact of incorporating Si3N4 on the microstructure and oxidation characteristics of the ZrB2–20vol% SiC–10 ZrC composite was investigated using the pressureless sintering method. The findings revealed.

- 1.

The ZSZN3 (3vol% Si3N4) sample, which had the highest density and density, as evident in the images and the slightest weight change, exhibited the highest oxidation resistance.

- 2.

As the structure's density increases, oxygen penetration is more effectively prevented. In contrast, among samples containing additives, the weight gain decreases up to 3% volume percentage of Si3N4, and from 3% volume, the weight gain increases to a lesser extent. This can be attributed to the increase in relative density and the decrease in porosity in lower than 4% volume, while in 4% volume and higher, it is due to the decrease in relative density and increase in porosity.

![BSE of the fabricated samples: (a) ZSZN1, (b) ZSZN2, (c) ZSZN3, and (d) ZSZN4 [14]. BSE of the fabricated samples: (a) ZSZN1, (b) ZSZN2, (c) ZSZN3, and (d) ZSZN4 [14].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000536/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)