BaFe12O19 (BFO) thin films have been grown on Si(100) substrates by magnetron sputtering from previously synthesized ceramic BFO targets and have been compositionally and structurally characterized. Films grow with the c-axis orientation and magnetization direction parallel to the sample plane. In addition, the magnetic coupling between the BFO film and a deposited cobalt overlayer was studied. Images of X-ray magnetic circular dichroism in photoemission microscopy show magnetic regions in the BFO layer with domain sizes of several micrometers and others without magnetic contrast, the latter attributed to the presence of hematite. Magnetic domains in the Co overlayer show no significant correlations with those in the BFO film, pointing to a negligible magnetic coupling.

Se han crecido películas delgadas de BaFe12O19 (BFO) sobre sustratos de Si(100) mediante pulverización catódica con magnetrón a partir de blancos cerámicos de BFO previamente sintetizados y se han caracterizado estructural y composicionalmente. Las películas crecen con el eje c cristalográfico y la dirección de imanación paralelos al plano de la muestra. Además, se ha estudiado el acoplamiento magnético entre la película de BFO y una capa de cobalto depositada sobre ella. Imágenes de dicroísmo circular magnético de rayos X en microscopía de fotoemisión muestran regiones magnéticas en la capa de BFO con dominios de varios micrómetros de tamaño, así como otras sin contraste magnético, estas últimas atribuidas a la presencia de hematita. Los dominios magnéticos en la capa superior de Co no muestran una correlación significativa con los de la película de BFO, lo que apunta a un acoplamiento magnético insignificante.

Permanent magnets are used in many applications, particularly in electrical generators and motors, for information storage, in sensors or in household appliances [1–3]. They are key elements for the “green” transition toward a more sustainable economy [4]. For these purposes modern rare-earths containing magnets such as those based on Nd-Fe-B with energy products (BH)max of up to 400kJm−3 show the best performance [5]. However, concerns about price, environmental impact and supply availability of rare earths have raised the attention to ceramic magnets, which are cheaper and more environment-friendly [6,7]. M-type ferrites, studied and commercialized since the 1950s [8], are particularly well suited for the purpose of substituting rare-earth based magnets in applications where the ultimate best characteristics are not required. Among these magnetic materials, barium hexaferrite (BaFe12O19, BFO) is widely used in permanent magnets in different devices due to its low cost and the high coercivities achievable [9].

The crystallographic structure of BFO, shown in Fig. 1, is that of an M-type ferrite. The representative member of this group of ceramic materials is magnetoplumbite PbFe12O19. This structure belongs to the hexagonal space group P63/mmc. It is characterized by a close-packed arrangement of oxygen atoms with the divalent (Ba2+ or Pb2+) and trivalent (Fe3+) cations occupying interstitial voids. It can be considered as a sequence of alternating spinel (S) and rocksalt (R)-structured blocks [10]. All the iron ions are in the Fe3+ oxidation state and can be found in five different environments, denoted by the 2a, 2b, 4f1, 4f2, and 12k sites according to the Wickhoff notation [6]. In the S block, four octahedral iron cations (2a and 12k) are aligned along the net magnetization direction and the two tetrahedral (4f1) ones along the opposite direction, i.e. they are antiferromagnetically coupled to the former. In the R block, two distorted octahedral sites (4f2) couple also antiferromagnetically to the octahedral sites (12k). There is also an unusual bipyramidal Fe site (2b), coupled ferromagnetically to the majority of octahedral sites. The easy magnetization direction coincides with the c-axis of the crystallographic structure and the compound presents a Curie temperature of 723K and a high magnetocrystalline anisotropy (Ku=3.25×105Jm−3) [11].

Barium hexaferrite crystal structure depicted by the VESTA program [12].

However, due to its moderate saturation magnetization, the energy product of BFO is significantly smaller, typically one order of magnitude, than those of rare-earth-based magnetic materials [7]. To overcome this drawback, it has been proposed to enhance the energy product by combining BFO as a magnetically hard component with a soft phase in order to improve the remanent magnetization without important losses in coercivity. So far, the results obtained in other hard/soft systems (Co/SrFe12O19 bilayers) have pointed out the difficulty of taking advantage of this magnetic coupling regime [13,14].

In this work, we report on the fabrication of BFO thin films by magnetron sputtering using home-made targets with subsequent annealing in air. The films were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Rutherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS) and were found to grow with their magnetic easy axis (the c-axis) oriented in-plane. On top of these films, we have deposited 5nm thick, magnetically soft Co layers by molecular beam epitaxy. The system was further characterized by Raman spectroscopy, vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). The magnetic domain structure, both of the BFO films and the Co overlayers was determined by X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) coupled to photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM).

ExperimentalBFO ceramic pellets to be employed as targets were synthesized following a previously reported calcination method [15]. BaCO3 and Fe2O3 powders (of purities higher than 99% and 96%, respectively) were supplied in a 17.5:82.5 weight ratio, which corresponds to a Ba:Fe=1:11.7 atomic ratio, and ball-mixed for 3h in ethanol medium. The resulting powders were left to dry in a drying oven and, after milling in an agate mortar and sieving, were heated for 3h at 1200°C. BFO powders were then sieved and pressed with an automatic pressing machine at 150kgcm−2. The target was sintered at 1300°C. Other Ba:Fe ratios close to stoichiometric BaFe12O19 were investigated, but X-ray diffraction results indicated an additional hematite phase due to unreacted iron oxide. A slight barium excess was therefore required. BFO films were deposited on Si(100) wafers by means of radio-frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering, with a typical power of 260W, inside a home-made vacuum chamber with a base pressure of 6×10−6mbar. In order to clean the 2″ target, a pre-sputtering of 15min was performed before film deposition. The sample-to-target distance was approximately 6cm. Substrates were kept at room temperature during deposition. The gas used was Ar with a small admixture (about 2%) of O2 at a working pressure of 6×10−3mbar. The growth process typically took a time of 30min. The films were afterwards annealed in air at 850°C for 3h. This procedure has been proved useful for the related SrFe12O19 material [14,16], and, as it will be seen below, the BFO films required this heating step to show a good crystalline structure [16]. After characterization of the BFO film, a thin cobalt film of 5nm thickness was deposited on the BFO film by molecular beam epitaxy at room-temperature in the ultra-high vacuum environment of the PEEM station of the CIRCE beamline [17] at the ALBA synchrotron (see below). For this purpose, a water-cooled home-made Co doser was employed, in which a high-purity Co rod (5mm diameter) is heated by electron bombardment [13,14]. Prior to Co deposition, the BFO film was gently heated to about 100°C for several seconds in order to remove possible adsorbed contaminants while avoiding modification of the surface structure or composition.

The crystallinity of both the BFO target material and the thin films was determined by X-ray diffraction with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer using Cu-Kα) (1.54Å) radiation in a (θ/2θ) configuration. The measurement step was 0.02°/s with a 0.5s measuring time per step.

The composition and thickness of the films were determined by Rutherford backscattering spectrometry using 4He+ ions at 2MeV. Experiments were performed at the standard beamline of the 5MV tandem accelerator of the Centro de Micro-Análisis de Materiales (CMAM) in Madrid [18], equipped with a three-axis goniometer. A silicon surface barrier detector was used mounted at a scattering angle of 170.0°. Analysis of the results was performed with simulations using the SIMNRA software package [19].

Integral conversion electron Mössbauer spectroscopy (ICEMS) data were recorded at room temperature from the thin films using a 57Co(Rh) source, a parallel-plate avalanche counter [20] and a conventional constant acceleration spectrometer. Transmission Mössbauer data of the BFO powders were recorded using a proportional counter detector. The velocity scale was calibrated using a 6μm thick α-iron foil. The spectra were computer-fitted and the isomer shift values were referred to the centroid of the spectrum of metallic iron at room temperature.

Raman spectra were recorded with a micro-Raman Via Renishaw spectrograph, equipped with an electrically cooled CCD camera and a Leica DM 2500 microscope. The laser excitation was set at 532nm by a Cobolt SambaTM DPSS laser. A diffraction grating of 1800l/mm was used.

Magnetic measurements were performed with a vibrating sample magnetometer equipped with a pair of home-made pick-up coils and a SR830 DSP lock-in amplifier. Sample and pick-up coils are placed inside the poles of an electromagnet capable of applying magnetic fields of up to about 18kOe depending on the gap opening. The applied field was measured by a Hall probe. The system was calibrated with iron powder samples of known saturation magnetization, with an estimated precision of about 2% and a resolution better than 5×10−4emu.

Characterization by X-ray absorption techniques was performed at the CIRCE beamline [17] of the Alba synchrotron. The system was studied by photoemission electron microscopy, X-ray absorption spectroscopy and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism imaging at the Fe and Co L2,3 absorption edges. XMCD images were obtained by subtracting pixel-by-pixel the intensities of pairs of images recorded with circularly polarized X-rays of opposite helicities.

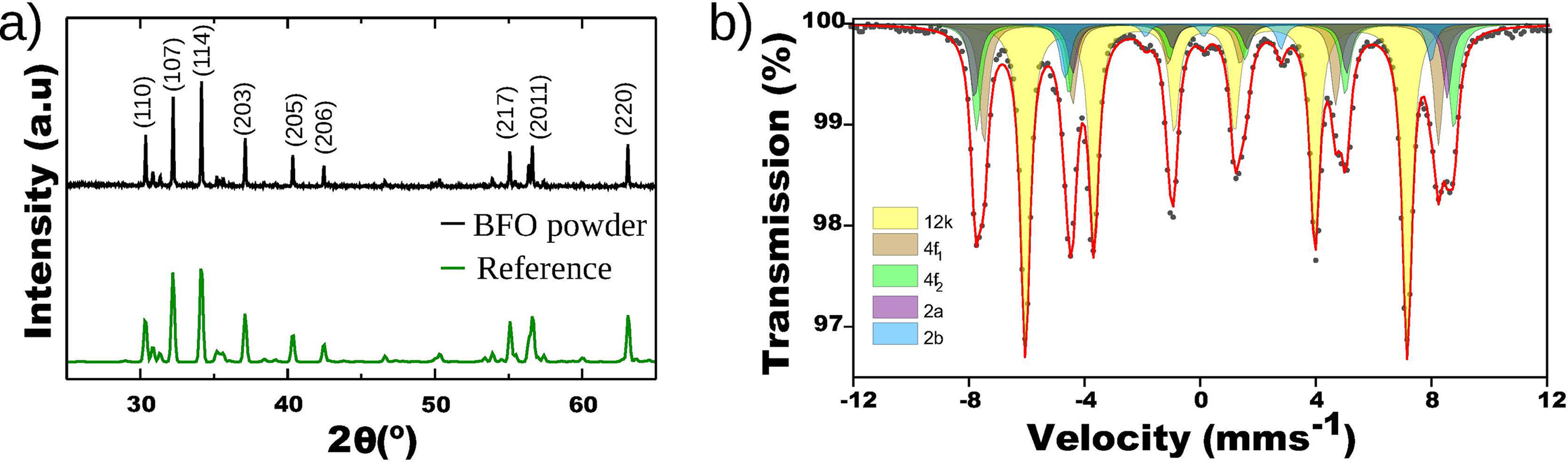

Results and discussionThe BFO powders produced by the calcination process as described in the previous section were characterized by XRD and Mössbauer spectroscopy. The corresponding XRD diffractogram is shown in Fig. 2a, together with that of a reference sample of barium hexaferrite (ICSD 259873 CIF file) [21]. All the diffraction peaks of the BFO powders correspond to those of the reference hexagonal structure of barium hexaferrite and no significant contribution from other phases can be detected. The small widths of the peaks indicate large typical sizes of the crystalline regions in the synthesized powders. These were further analyzed by Mössbauer spectroscopy in transmission geometry. The measured Mössbauer spectrum is shown in Fig. 2b. It was fitted to five sextets, each one arising from a different iron site within the BaFe12O19 structure (see Fig. 1, where the color of each site correlates with the respective contribution to the fitted Mössbauer spectrum). The values obtained for the hyperfine parameters are summarized in Table 1. These results are in good agreement with previously published data for this compound [22,23]. Furthermore, the relative intensity of the absorption lines of a sextet contains information on the average orientation of the magnetization in the sample respect to the incoming γ-ray direction [24]. Here, the spectral areas closely follow the ratio 3:2:1:1:2:3, which indicates a random orientation of the magnetization, as expected for a powder sample.

Mössbauer parameters obtained from the fit of the spectrum in Fig. 2b recorded at 295K in transmission mode from the BFO powder. The symbols δ, 2ɛ, H, Γ correspond to isomer shift, quadrupole shift, hyperfine magnetic field and linewidth, respectively. A is the relative area of each component.

| Site | δ (± 0.03mms−1) | 2ɛ (± 0.05mms−1) | H (± 0.01T) | Γ (± 0.03mms−1) | A (± 5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12k | 0.35 | 0.38 | 41.0 | 0.38 | 50 |

| 4f1 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 48.8 | 0.40 | 19 |

| 4f2 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 51.2 | 0.40 | 16 |

| 2a | 0.35 | 0.04 | 50.8 | 0.36 | 10 |

| 2b | 0.37 | 2.52 | 39.5 | 0.34 | 5 |

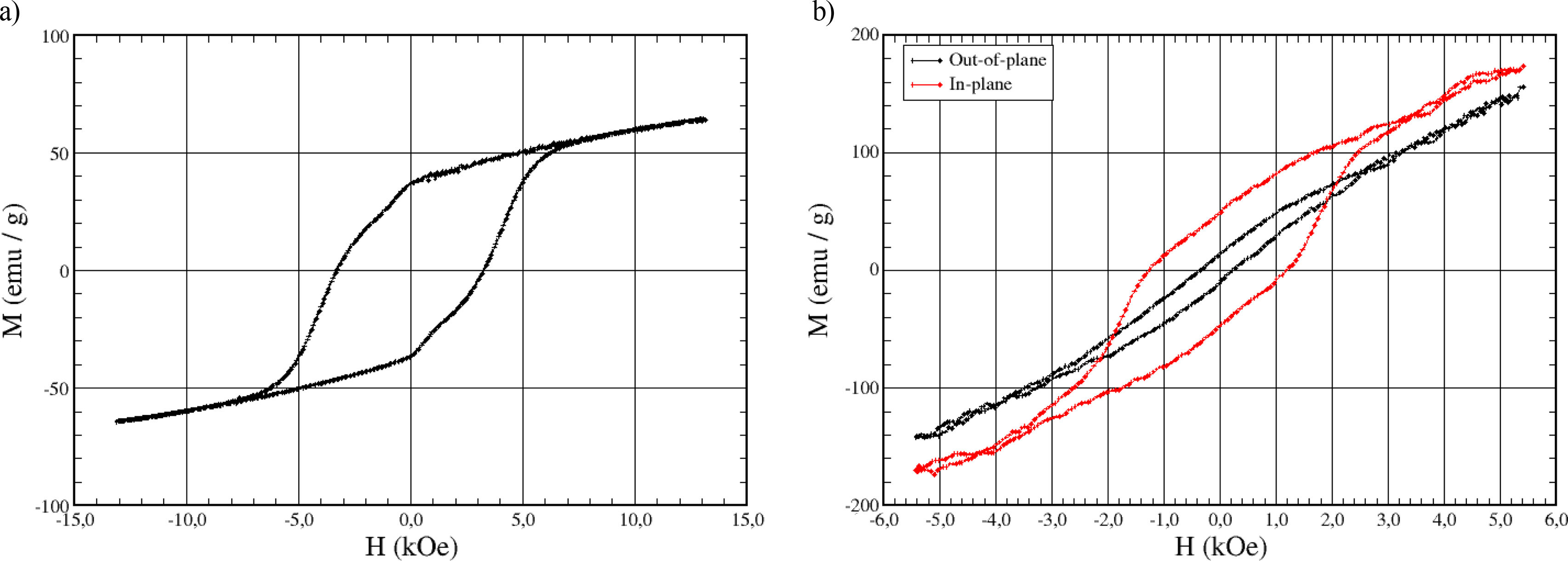

Finally, hysteresis loops of the BFO powders were recorded with a home-made VSM at room temperature. The result is shown in Fig. 3a. A value for the coercive field of 3.3kOe is obtained, as well as a remanence of 37emu/g and a magnetization of about 67emu/g at 15kOe. These results are similar to those obtained for comparable bulk BFO samples [25].

The BFO films deposited on Si (100) by magnetron sputtering were characterized by RBS and XRD in order to study their chemical composition and structure. Fig. 4(a) and (b) shows experimental RBS spectra corresponding to the as-grown and the annealed films, respectively. They were acquired in a random direction of incidence of the incoming ions. The figure includes the result of the simulations performed containing the specific contribution of each of the elements expected to be present in the film (Ba, Fe, O) as well as Si in the substrate. The chemical compositions, as determined by RBS, are very similar, although the Fe/O ratios, 0.52 and 0.55, obtained for the non-annealed and annealed samples, respectively, are slightly lower than the stoichiometric one corresponding to the pure BFO phase, 0.63. The thickness of the as-grown film was determined to be 390nm, while for the annealed film it was 407nm. While the difference amounts to less than 5% and is therefore close to the resolution limit of the RBS technique, the variation might be related to the crystallization process taking place on annealing, as shown below by XRD, possibly associated with slight changes in the oxygen content of the film.

Rutherford backscattering spectra recorded from the as-grown and annealed BFO films, respectively. The spectra simulated with the SIMRA software for each sample are represented by the blue lines, the contribution of the different elements by the colors as shown in the legends. (c) X-ray diffraction patterns of the BFO target powder and the as-grown and annealed films.

Fig. 4(c) presents the diffractograms of the as-grown and annealed films, together with the one of the target material. For the as-grown sample only a broad feature is detected at 62.5° in addition to the diffraction peaks arising from the Si(100) substrate. This means that this sample is basically amorphous or has a very low degree of crystallinity. On the other hand, the XRD signal of the annealed film shows the sharp peaks indicative of a crystalline structure, which can be identified as a barium hexaferrite phase with a predominant c-axis orientation within the surface plane [26], as the intensity of the hkl-peaks with ab character (e.g. hh0) grow while reflections with predominantly c character (e.g. 107, 114) decrease, as compared with the diffractogram of the BFO target material. Since for M-type ferrites the c-axis of the crystal coincides with the easy direction of the magnetization, it can be inferred that the annealed BFO sample has its magnetic easy axes in the film plane.

On top of the annealed BFO film, a thin cobalt layer of 5nm thickness was deposited by molecular beam epitaxy at room temperature, in order to avoid interdiffusion of Co into the BFO film. Subsequent in situ characterization was performed by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) in photoemission microscopy (PEEM). The system was further characterized ex situ by Raman and Mössbauer spectroscopies and by VSM.

X-ray absorption spectra were recorded for the two opposite helicities of circularly polarized incoming radiation by scanning the photon energy and recording by PEEM the secondary electron intensity within selected windows covering the magnetic single domains visible on the surface (these domains can be detected by the XMCD contrast, see below). The sum of the two spectra for the opposite helicities gives the XAS spectrum and the difference gives the XMCD spectrum. Both are shown in Fig. 5(a and b) in the regions of the Fe and Co L2,3 absorption edges, respectively. The Fe signal provides information on the BFO film, whereas the Co signal originates from the deposited overlayer. The Fe XAS spectrum corresponds to the one expected for a barium hexaferrite compound, in which Fe ions have a 3+ valence state [27]; the characteristic XMCD peaks point out the different arrangement of the ions in the crystal structure (octahedral, bipyramidal and tetrahedral) and their intrinsic dichroic behavior [27,28]. The XAS spectrum at the Co L2,3 absorption edge indicates the presence of metallic cobalt [29]. In this spectrum, there are two additional peaks visible at nominal photon energies of 783.8 and 798.0eV, which can be attributed to the Ba M5 and M4 edges arising from the BFO film [30]. The Co L3 edge shows an appreciable signal also in the XMCD spectrum.

(a) and (b) XAS and XMCD spectra in the regions of the Fe and Co L2,3 absorption edges, respectively, of the Co/BFO structure. (c) and (d) XMCD images at the Fe and Co L3 absorption edges, photon energies of 709.4eV and 778.5eV, respectively. The maximum asymmetry between white and black domains in (c) amounts to 0.69.

Fig. 5(c) and d) shows XMCD-PEEM images acquired at the Fe and Co L3 edges, at the nominal energies of 709.4eV and 778.5eV, respectively, determined from the spectra of Fig. 5(a) and b) in order to maximize the corresponding dichroic signals. A clear magnetic contrast can be seen in Fig. 5c. Specifically, three distinct regions can be observed, two with extreme intensities, called “black” and “white” regions (integrating the intensity inside each type of domains allows the recording of the absorption spectra previously described). The domains have sizes of several micrometers. Since the incoming X-rays enter the sample at an angle of 16°, i.e. close to gracing incidence, the orientation of the magnetization must lie at least partly in the plane of the film. Additionally, a third “grey” domain type is observed, intermediate in contrast. In principle, these regions could be either nonmagnetic or have magnetization perpendicular to the X-ray incidence. Further analysis favors the first possibility, as will be shown below. Magnetic contrast can also be detected in the XMCD image at the Co L3 edge (Fig. 5d), but the size of the domains is here much smaller, typically less than 1μm. There is no obvious spatial correlation between these domains and those found at the Fe edge.

Next, the sample was rotated around its surface normal by 60° and 120° respect to the orientation of the first measurements. In this way the azimuthal orientation of the incoming X-ray beam with respect to the sample surface was varied. The corresponding dichroic images are shown in Fig. 6 (after having been rotated back in order to present the same orientation in the figures). It can be seen in the signal at the Fe edge, corresponding to the BFO film, that the contrast changes in the domains “black” and “white” depending on the azimuthal orientation of the incoming X-rays, confirming the magnetic origin of the contrast. This further supports the fact that the magnetization lies in the surface plane. However, the “grey” domains do not change upon rotation, which points at the presence of a non-magnetic phase. On the other hand, there is a similar level of contrast of the domains observed at the Co edge for all orientations, showing again no correlation with the domains at the Fe edge.

Previous work of our group has found two examples of a similar behavior in the related material strontium hexaferrite (SFO). In the case of SFO platelets capped by a cobalt overlayer, non-correlated magnetic domains in SFO and Co were found [13]. This was rationalized as a consequence of the shape anisotropy of the in-plane magnetized soft Co layer dominating over the effect of the stray field produced by the perpendicularly magnetized hard SFO film. In a second study, an alignment of the magnetization uniaxial easy axes of SFO films and Co overlayers, both in-plane, was detected, but no correlation between their magnetic domains was found either, pointing at a structural but not exchange coupling between both films in the bilayer structure [14]. The conclusion that neither magnetic nor structural coupling occurs in the present study of the Co/BFO system fits therefore well in the light of the previous observations. It is important to understand that in order for exchange coupling (and subsequent magnetic domain matching between two layers in a heterostructure) to occur, orbital overlap at the atomic level at the interface needs to take place. In the system studied here it is rather difficult to generate coherent bonding at the interface between the Co and BFO layers given that the Co overlayer is grown at room temperature, and in that sense exchange coupling is rather unexpected. The second most common magnetic interaction in these bilayer systems is the dipolar interaction, which is surely occurring at the interface. However, the larger magnetization of Co with respect to BFO allows us to assume that the self-demagnetizing fields of the Co layer itself have to be larger than the stray fields generated by the BFO underlayer. These considerations are thus in agreement with the magnetic domain mismatch and the lack of coupling between the two layers.

A further interesting aspect to address is the presence of the non-magnetic areas observed by XMCD-PEEM on the BFO film. In order to shed light on the nature of these regions, Raman and Mössbauer experiments were performed on the bilayer system. Fig. 7 shows Raman spectra acquired at different locations on the sample, chosen with the help of optical microscopy images like the one in the insert. Three spectra are displayed: one taken at the majority, “brown” zones, another at the “green” zones and a third, reference one, measured on the BFO target used to grow the films. There is a close correspondence between the vibrational bands observed in the majority regions of the film and in the target. In particular, the Raman modes characteristic of BFO are identified (410, 620, 688 and 734cm−1). They can be related and indexed according to the results published for canonical barium hexaferrite [31–33]. However, in the “green” zones, in addition to the main peaks, also detected, as discussed above, in the majority regions and in the powder, there are additional peaks that do not appear in the BFO spectrum, such as the modes corresponding to 225 and 292cm−1. Such vibration modes can be attributed to Fe2O3 (hematite) [34,35]. This fact is compatible with the RBS results, as the films were found to have a lower iron content than expected for stoichiometric BFO, allowing a possible contribution from iron vacancies or other compounds. Furthermore, hematite is not expected to give XMCD contrast due to its antiferromagnetic nature [36], so the regions with zero Fe XMCD signal can be attributed to the presence of Fe2O3 in such areas.

Fig. 8 presents the Mössbauer spectrum of the film including the result of a fit to a model containing the same components as the ones used for the BFO powder [22,23] plus an additional one. The values of the hyperfine parameters obtained from the fit are collected in Table 2. The additional contribution, a sextet (colored gray in Fig. 8) with an isomer shift of 0.38mms−1, a hyperfine magnetic field of 50.7T and a very characteristic quadrupole shift of −0.22mms−1, corresponds unequivocally to hematite [37,38]. The amount of this phase as determined by Mössbauer spectroscopy is approximately 10%. All the other contributions, arising from the BFO phase, are present in the same relative proportions as found for the target, within error bars. This result supports the conclusions of the Raman analysis, which ensure the presence of hematite in the barium hexaferrite film. This can be correlated with the non-magnetic regions detected in the XMCD-PEEM images, whose extension can be enhanced in the surface region. Also, it confirms the predominant orientation of the magnetization in the film plane, since the ratio of intensities in the peaks of the current spectrum is 3:3.2:1:1:3.2:3, giving rise to an average magnetization close to the sample plane (average angle of 70° respect to the surface normal). The values of the hyperfine parameters obtained from the fit are collected in Table 2.

Mössbauer parameters obtained from the fit of the spectrum of the BFO/Co bilayer recorded at 295K in electron detection mode (Fig. 8). The symbols δ, 2ɛ, H, Γ correspond to isomer shift, quadrupole shift, hyperfine magnetic field and linewidth, respectively. A is the relative area of each component.

| Site | δ (± 0.03mms−1) | 2ɛ (± 0.05mms−1) | H (± 0.01 T) | Γ (± 0.03mms−1) | A (± 5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFO 12k | 0.35 | 0.39 | 40.3 | 0.44 | 48 |

| BFO 4f1 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 48.7 | 0.41 | 15 |

| BFO 4f2 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 50.5 | 0.40 | 13 |

| BFO 2a | 0.31 | 0.04 | 50.0 | 0.40 | 9 |

| BFO 2b | 0.29 | 2.32 | 39.0 | 0.30 | 5 |

| Fe2O3 Oh | 0.38 | -0.22 | 50.7 | 0.30 | 10 |

Additional magnetic characterization of the Co/BFO layered structure was performed by recording hysteresis loops by VSM at room temperature. The result is shown in Fig. 3b for external magnetic fields applied both parallel and perpendicular to the layers. The contribution of the very thin Co layer is below the sensitivity limit of our VSM setup, while the antiferromagnetic hematite identified as a secondary phase is not expected to contribute to the magnetization of the film. It can be seen that the direction of easy magnetization is parallel to the sample plane, confirming our previous results. For the in-plane curve, after subtraction of the paramagnetic signal of the substrate, a coercive field of 1.8kOe is found, while for the magnetization at 5kOe a value of about 45emu/g can be determined; this represents a reduction of about 10–20% compared with the magnetization of the bulk target material (50–55emu/g) at this value of the external field. Experimental results are thus compatible with the presence of hematite in the deposited films. While work is planned to achieve BFO films free of this secondary contribution, under the present conditions, the magnetic parameters obtained for our films correlate quite well with those reported for comparable barium hexaferrite thin films [39].

SummaryBFO Ceramic targets have been synthesized by the calcination method with BaCo3 and Fe2O3 as precursors and used to grow films by magnetron sputtering on Si(001). XRD shows that the BFO films grow with the c-axis direction parallel to the sample plane. VSM, XMCD-PEEM and Mössbauer spectroscopy confirm the magnetization in-plane orientation. XMCD-PEEM shows magnetic and non-magnetic areas in the BFO layer, the latter attributed to the presence of hematite as detected by Raman and Mössbauer spectroscopies. The magnetic domains have sizes of several micrometers, very large for a thin film. The magnetic domains of a cobalt overlayer deposited onto the BFO film are smaller and not correlated with the magnetic domains in the BFO surface, pointing to the absence of any relevant exchange-based magnetic coupling, which is interpreted as the consequence of a lack of structural coherence at the film's interface. The results shed light on the important topic of exploiting coupling mechanisms at surfaces and interfaces to improve the properties of magnetic metal-ceramic hard-soft magnetic materials.

This work was supported by Grants TED2021-130957B-C54 and TED2021-130957B-C51, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”, by Grants PID2021-124585NB-C31, PID2021-124585NB-C33 and PID2021-122980OB-C54, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe” and by the BEETHOVEN project funded by the European Commission under grant agreement 101129912. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them. C.G.-M. acknowledges financial support from grant RYC2021-031181-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. We acknowledge support from CMAM for the beamtime proposal STD009/20.

![Barium hexaferrite crystal structure depicted by the VESTA program [12]. Barium hexaferrite crystal structure depicted by the VESTA program [12].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000408/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)