In July 2022, an extensive outbreak of Mpox (monkeypox) was considered by WHO as a Public Health Emergency. The objective of this study is to describe the obtained results from a Mpox case detection program in a semi-urban healthcare area where approximately 420 Primary Care physicians work.

DesignAn observational prospective study performed between June 01, 2022 and December 31, 2023.

SettingThe Northern Metropolitan area of Barcelona, with 1400.000hab (Catalonia, Spain).

MethodsAn unified Mpox management procedure was agreed, including a prior online training of Primary Care professionals, to individually assess all Mpox suspected cases from a clinical and epidemiological perspective.

ParticipantsAll patients who met clinical and/or epidemiological criteria of Mpox.

Data collectionAge, gender, risk classification (suspected/probable), cluster-linked (yes/no), high-risk sexual contact (yes/no), general symptoms, genital lesion and final diagnostic.

ResultsA total of 68 suspected Mpox cases were included, from which 16 (26.6%) were Mpox confirmed by PCR. Up to 13 (81.2%) were male and, among them, 12 (75%) men who have sex with men (MSM). The series, however, included two minors and three women. Among MSM, 3 (18.7%) were HIV positive and 3 had no regular access to the Public Healthcare system. Among discarded patients, any infectious disease was diagnosed in 55% of cases.

ConclusionsIn spite of the short series, this Primary Care community-based study identified a sub-population group showing a different profile of Mpox cases compared to other published series (lower HIV prevalence, higher representativeness of heterosexual transmission and hard to reach population).

En julio de 2022 la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) declaró una epidemia de viruela simiana (Mpox) como Emergencia de Salud Pública. El objetivo del estudio es describir los resultados obtenidos por un programa de detección de casos de Mpox en un área semirural de la zona metropolitana norte de Barcelona donde ejercen aproximadamente 420 médicos de Atención Primaria.

DiseñoEstudio observacional prospectivo llevado a término entre 01 junio de 2022 y 31 diciembre de 2023.

EmplazamientoÁrea Metropolitana Norte de Barcelona; con 1.400.000 habitantes (Cataluña, España).

ParticipantesTodos los pacientes que reunían criterios clínicos y/o epidemiológicos de Mpox.

MedicionesEdad, género, nivel de riesgo (sospechoso/probable), brote epidémico (sí/no), contacto sexual de riesgo (sí/no), síntomas generales (sí/no), presencia de lesión genital (sí/no) y diagnóstico final.

ResultadosUn total de 68 casos sospechosos de Mpox fueron incluidos, de los que 16 (26,6%) fueron confirmados por proteína C reactiva (PCR). Eran hombres 13 (81,2%) y, de ellos, 12 (75%) eran hombres que tienen sexo con hombres (HSH). El estudio, identificó a dos menores de edad y tres mujeres. Entre los MSM, tres (18,7%) eran positivos al virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH), y tres más no disponían de cobertura sanitaria pública. De los pacientes descartados de Mpox, un 55% fueron diagnosticados de alguna enfermedad infecciosa.

ConclusionesA pesar de lo limitado de la serie, un estudio de base comunitaria en Atención Primaria identificó un subgrupo de pacientes con un perfil diferente (menor prevalencia de VIH, presencia de casos en heterosexuales y entre población marginal) de lo publicado en otros estudios basados en centros especializados en enfermedades de transmisión sexual.

In May of 2022, a clustered of cases of Mpox virus (formerly Monkeypox) was identified in men who have sex with men (MSM) in UK without history of recent travel to endemic countries.1 A sub-sequent epidemic outbreak was declared and soon after cases were reported in several countries. In July 2022, the epidemic was declared a Public Health emergency alarm of international concern by the WHO.2 The number of cases peaked on August of this same year with as much as 7000 new cases declared each week, with a steadily decreased later on. Cases have been declared in almost all countries of the world at the beginning of 2023 up to a total of 85,473 confirmed cases at the WHO by January 2024.3 Previously, the Mpox – an Orthopoxvirus closely related with the variola virus, the causative agent of the human smallpox –, was considered a zoonotic tropical disease which occasionally spill over from Central African apes (the main natural reservoir) to humans, with few recorded cases and limited outbreaks.4–6

The clinical presentation at onset was – after an incubation period between 7 and 14 days – a febrile prodromal for 1–4 days companied by headache, muscle aches, sore throat and sometimes exhaustion, sweats and fatigue. Lymphadenopathy and skin rashes appear 1–3 days after the onset of fever. The rash typically can appear on the face, eyes, inside the mouth, on the hands, feet, chest and genitals and/or anus. It evolves from macula to papule and crusted pustules in a lapse of approximately 14–28 days.7 The disease – at least those caused clade I – is usually mild with the attributable mortality (up to 1–3%) restricted to immunosuppressed individuals. The epidemiological tracing soon after the outbreak recognized the monoclonal origin, with a striking homogeneous epidemiological profile associated: the majority of cases were transmitted through close sexual contacts among MSM which, in turn, determined particular clinical presentations frequently related to the local inoculation site (i.e. proctitis, tonsillitis, etc.), followed by general signs and symptoms secondary to viremia.8–13 Furthermore, all published series point out the important overlap with HIV infection (between 30 to up to 50% were co-infected), the frequent coinfection with other sexually transmitted infections (STI's) (i.e. Syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia), and the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).3,12,13

STI clinics or checkpoints played the leading role in publishing Mpox management guidelines that were urgently needed at the start of the epidemic. Nevertheless, Primary Care professionals should have a relevant role as a frontline of the health system in the community, which have access to sets of population that are not in the radar of usual devices focused on populations at most risk. Obviously, doubts concerning diagnosis, management, prognosis and possible complications were expected to arise among these first-line professionals facing a pathogen never seen before. With the aim to support Primary Care professionals, a Mpox Guideline was agreed in 2022 June,14 and a device system to support the identification and research of suspected cases was stablished. The objective of this work is to describe the obtained results in a semi-urban healthcare area where approximately 420 Primary Care physicians work.

Material and methodsStudy settingThe study area comprised the northern crown of the greater North Metropolitan Area of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain) attended by 64 Primary Care teams belonging to the Institut Català de la Salut, with 1,400,000 inhabitants spread over 71 municipalities. All them are funded by the Catalan Health System public insurer (CatSalut), then universally accessible and free of charges.

Description of the community-based deviceAn online training was provided to Primary Care professionals, alongside a distribution of guidelines for early identification of suspected or probable Mpox cases.14 Moreover, a supporting, reference, unit (International Health Program Unit) was designed to provide advice to any suspected case if needed, discuss including clinical and epidemiological aspects, and to reach a consensus of whether to obtain biological sample for testing or other additional testing, clinical and epidemiologic management and necessary interventions, including contact tracing and isolation measures to be implemented. Most of this activity was carried out online between June 01, 2022 and December 31, 2023.

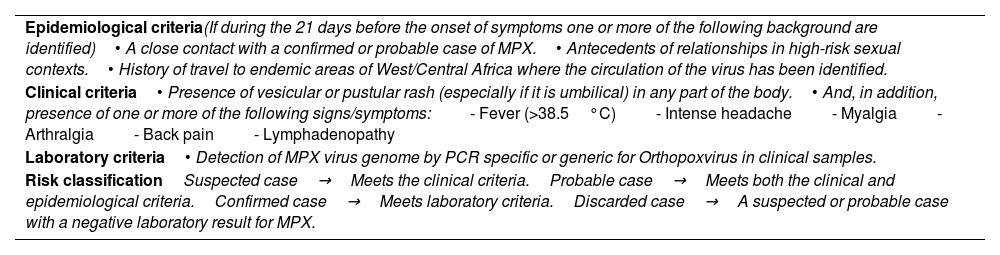

Inclusion criteria of Mpox casesAccording to the guidelines developed, patients were classified as “suspected”→“probable”→“confirmed” and “discarded” in relation of the fulfillment of epidemiologic, clinical and laboratory criteria shown in Table 1.

MKPX inclusion criteria and risk classification.

| Epidemiological criteria(If during the 21 days before the onset of symptoms one or more of the following background are identified)• A close contact with a confirmed or probable case of MPX.• Antecedents of relationships in high-risk sexual contexts.• History of travel to endemic areas of West/Central Africa where the circulation of the virus has been identified. |

| Clinical criteria• Presence of vesicular or pustular rash (especially if it is umbilical) in any part of the body.• And, in addition, presence of one or more of the following signs/symptoms:- Fever (>38.5°C)- Intense headache- Myalgia- Arthralgia- Back pain- Lymphadenopathy |

| Laboratory criteria• Detection of MPX virus genome by PCR specific or generic for Orthopoxvirus in clinical samples. |

| Risk classificationSuspected case→Meets the clinical criteria.Probable case→Meets both the clinical and epidemiological criteria.Confirmed case→Meets laboratory criteria.Discarded case→A suspected or probable case with a negative laboratory result for MPX. |

A high-risk sexual contact was defined as vaginal, anal or oral insertive or receptive practice without protecting barrier-method and with unknown partnerships. Discarded cases were studied and followed up as far as possible with the aim of obtaining a definitive diagnosis.

Laboratory testingA confirmed case of Mpox was defined as a positive result of a real-time PCR (LightMix Modular Monkeypox Virus©; TIB MolBiol, Berlin, Germany) assay of skin lesion, anal, urethral or oropharynx swabs samples. All samples were sent refrigerated in viral transport media ensuring biosafety to the Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol (Badalona, Catalonia, Spain) Microbiology Service, acting as the only centralized territorial laboratory. To prevent false negative results due to the presence of inhibitors, unsuccessful extraction of nucleic acid, degraded target material or incorrect sampling we used LightMix Modular MSTN Extraction Control© (TIB MolBiol, Berlin, Germany) as internal control. In addition, and simultaneously, skin and rectal, urethral or oropharyngeal swabs (when symptomatology) were real time-PCR tested for Haemophilus ducreii, Chlamydia trachomatis L1–L3, herpes simplex virus 1–2, varicella zoster virus cytomegalovirus and Treponemapallidum by means of a Multiplex RT-PCR assay (Allplex™ Genital Ulcer Assay©; Seegene Inc, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and independently, if indicated (clinical symptoms): Gram stain and bacterial culture of ulcerative lesions, STI serology (including fourth generation HIV test) and first-void urine RT-PCR for C. trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Mycoplasma genitalum, Trichomonas vaginalis and Ureaplasma urealyticum (Allplex™ STI Essential Assay©; Seegene Inc, Seoul, Republic of Korea).

ProceduresPrimary Care professionals (working whether in regular attendance or emergency area) attending a suspected case must: (1) obtain samples from suspected lesions, (2) activated the biosafety transport plan, (3) stated the suspicion to the Territorial Public Health Unit (the body in charge of epidemiological surveillance) and, (4) reported clinical and epidemiological data to the International Health Program Unit. The professionals assigned to the International Health Program supported the coordination of the whole process and acted as referrals in case of necessity either for the correct classification of the suspected case, clinical management, advice on diagnostic procedures (for Mpox and other overlapping or possible co-occurring diseases), biosafety and epidemiological countermeasures to be implemented. Professionals from the reference team were contacted online. The information provided included high-resolution pictures of the lesions, all clinical and epidemiological data available. Throughout the process, patients received timely information. Suspected cases were kept in isolation and sexual abstinence was prescribed until reception of the laboratory results. Confirmed cases (RT-PCR positive) extended isolation and biosafety measures up to 14 days. A phone-based follow-up clinical check was carried out by their Primary Care physicians in a daily basis. In-house visits were done if necessary. A contact study was carried out. A contact was considered any sexual contact (protected or unprotected), during the 21 days’ prior the onset of symptoms, as well as housemates. Post-exposure prophylaxis with vaccination was indicated as soon as it became available. Prudential isolation and/or sexual abstinence was advised to all contacts at risk identified during the following 14 days after the last contact with the confirmed case. Self-surveillance of clinical signs and symptoms was stablished among these contacts.

Data collection and statistical analysisClinical and socio-demographic data including age, gender, risk classification (“suspected” if meets clinical or epidemiological criteria/“probable” if meets both criteria/“confirmed” if RT-PCR resulted positive/“discarded case” when a suspected or probable case with a negative laboratory result for MPX), cluster-linked (“yes” when an epidemiologic relation with a confirmed case was identifiable/“no” when it did not) high-risk sexual contact (“yes” if background of relationships in high-risk sexual contexts within the previous 21 days were recorded/“no” if did not), general symptoms (fever/arthralgia/myalgia/back pain), genital lesion (yes/no) and final diagnostic were collected from the routine electronic clinical records, anonymized for analysis purposes so that researchers had no access to information that would identify participants personally. Categorical variables were described as proportions and continuous variables as means or median/mean and ranges/SD, as appropriate. Bivariate analysis was carried out using Chi-square test or T-Student for categorical or continuous variables, respectively, or their non-parametric counterparts when necessary (Fisher exact and Wilcoxon test). Data was analyzed using the statistical package Stata vs. 14.0.

ResultsA total of 68 (mean age of 30.04 years, SD=+14.8 years) suspected cases were included; of them, 8 (11.8%) were initially dropped after a jointly evaluation between the Primary Care physician in charge and the supporting team, due to non-compliance with both epidemiological and clinical criteria. Of the remaining individuals, 16 (26.6%) out of 60 individuals resulted in a Mpox virus-PCR positive (confirmed cases) (Fig. 1). The clinical and epidemiological description is shown in Table 2. Diagnostics at the end of the healthcare process from all the individuals screened (n=60) are displayed in Table 3.

Included cases. Initial risk classification (N=60).

| Confirmed cases (n=16) | Discarded cases (n=44) | Total (n=60) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 13/16 (81.2%) | 30/44 (18.8%) | 43 (71.7%) | 0.3 |

| Female | 3/16 (18.8%) | 14/44 (81.3%) | 17 (28.3%) | |

| Risk classification | ||||

| Initially “suspected” | 6/16 (37.5%) | 36/44 (81.8%) | 42 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Initially “probable” | 10/16 (62.5%) | 8/44 (18.2%) | 18 (30%) | |

| Cluster-linkeda | ||||

| Yes | 2/16 (12.5%) | 0 | 2/16 (12.5%) | |

| No | 14/16 (87.5%) | 0 | 14/16 (87.5%) | |

| Previous high-risk sexual contact (<21 days) | ||||

| Yes | 14/16 (87.5%) | 8/44 (18.2%) | 22 (36.7%) | <0.001 |

| No | 2/16 (12.5%) | 36/44 (81.8%) | 38 (63.3%) | |

| General symptoms | ||||

| Yes | 12/16 (75%) | 28/44 (63.6%) | 40 (66.7%) | 0.4 |

| No | 4/16 (25%) | 16/44 (36.4%) | 20 (33.3%) | |

| Genital/anal lesion | ||||

| Yes | 13/16 (81.2%) | 8/44 (18.2%) | 21 (35%) | <0.001 |

| No | 3/16 (18.7%) | 36/44 (81.2%) | 39 (65%) | |

| Fever+skin+linph | ||||

| Presence | 7/16 (43.7%) | 8/44 (18.2%) | 15 (25%) | 0.04 |

| Absence | 9/16 (56.3%) | 36/44 (81.2%) | 45 (75%) | |

Final diagnostics; cases with MPXV PR-PCR negative or not indicated (N=52 cases, 54 diagnostics).

Briefly, among Mpox confirmed cases fifteen (93.7%) of the 16 were positive in the swab test obtained at the time of diagnosis, and 1 was negative in the first instance but positive two days later. The median age was of 33 years (range 3–58), 13 (81.2%) were male, and they were residing at the moment of diagnostic in up to 11 different municipalities from the study area. Three out of 16 (18.7%) of them had no regular access to the public healthcare system (2 foreign visitors and 1 homeless) and 2 more have had background of traveling abroad within the previous 21 days (Senegal and Morocco, respectively). Up to 3 had HIV co-infection (18.7% prevalence; two of them with a previously known infection) and one (HIV+) coursed with a bacterial local superinfection. However, no severe complications, hospital admissions or antiviral treatment were prescribed to any patient. None of them have received anti-Mpox vaccination. A 75% (12 individuals) were MSM. Among those who reported to being mon-MSM (N=4; 25%) two were women – infected from their current male sexual partner – and one was a man with self-referred background of heterosexual contact with bisexual partners. One woman was infected by close house contact.

A formal tracing contact study was implemented among 22 (36.6%) of suspected cases prior getting definitive results and 56.3% among those which resulted as confirmed cases. A final diagnose for Mpox-PCR discarded cases at the end of the healthcare was achieved in process are displayed in Table 3.

DiscussionEurope and the Americas witnessed a fast expansion of until then considered an exotic disease, which have mainly affected a subset of MSM population. This particular population is characterized by being decidedly mobile and to be involved in dense sexual networks of highly risky behaviors.15–17 This explained the overrepresentation of PrEP users and the consistent high prevalence of HIV coinfection among Mpox confirmed cases.6–15 As reported, the expansion of Mpox virus was mostly drove by mass events occurring in some locations with further expansion to the countries of origin of participants.18 Spain swiftly rose to the top of the affected countries due to the concurrence various social factors: it is a popular destination of gay tourism and hosts of considerable number of summer mass gathering events. So far, up to 7800 cases have been recorded in our country.19 This represents the third highest prevalence, only surpassed by Brazil and the USA.3

Once the risky epidemiological profile was defined, specific countermeasures were settled up to target the population most at risk but, in the whole, these sets of populations have had privileged access to specialized premises like check-point centers (centers devoted to the counseling and rapid screening of STI's), and STI's clinics. These premises are most frequently linked to tertiary hospitals.20 In contrast, patients at risk or susceptible to the infection outside of these core populations could have been inadvertently skipped. The role of these populations in the maintenance and further spread of the infection should be not underestimated, especially during the first stages of an outbreak when the infectiousness has not yet been well determined. Therefore, it makes sense to strengthen the case-detection through the Primary Care services, the first line of the health system in Spain at community level. The case series diagnosed clearly show a different profile from those detected (and published) in specialized sexual health centers or fully urban and touristic areas. First, up to 17 women were initially assessed (28.3%), and accounted for 18.7% of the total confirmed series. This is in sharp contrast with the contemporary Spanish data published by Tarín-Vicente et al. (women=3%),12 Girometti et al. (0%)9 or by the multinational GeoSentinel Network (0%).21 Our study also includes two young confirmed cases (a confirmed aged 3 and a discarded aged 17), which have been rarely reported in other studies. These young cases deserve close inspection given the important Case Fatality Rate observed among children in endemic countries (up to 15% in endemic countries)22 and the social alarm that this might produce, including the media pressure in involved schools or kinder garden.23

Secondly, prevalence of high-risk sexual intercourse was also lower than previously studies in both confirmed and discarded individuals; indeed, two confirmed cases were from a heterosexual contact through the current sexual partner or aroused from a close household contact. Otherwise, the prevalence of HIV was much lower than all the published series.3,8–13 Finally, the program successfully reached three hard-to-reach cases which would have never attended any specific Mpox virus screening device (one tourist and two illegal migrants).

The clinical presentation of confirmed cases does not differ from what has been published so far, being the most characterized features have genital/anal lesions or show the Fever+Skin+Lymphadenopathy triad as more prevalent symptoms. The presence of general symptoms such as fever, asthenia, malaise o headache – despite being frequent – were rather unspecific.

We should note that contact tracing process faced significant constraints. As in other STI's, implementing a contact tracing study from Mpox index cases is difficult due to the inherent limitations of confidentiality data, the frequent evasiveness regarding the index cases, the existence of sexual relations with unknown partners and the frequent short-stay of contacts in the area (i.e. tourists).

However, a remarkable achievement from our cases series was that a final diagnosis among discarded patients was reached in 75% of screened cases. It should be noticed that up to 30 out of 54 non-Mpox diagnosis harbor had an infectious disease – STI or not –, which needed a careful follow-up. This is according to previous reports with prevalence of any STI co-infection from 17% to 74%.24 This points out to the necessity of enlarged screening diagnostics in the frame of any outbreak. This was noticed as well in countries until now considered endemic of Mpox, with frequent overlapping diagnosis with Varicella Zoster infection.25 A closer analysis of suspected cases and the availability of a broader spectrum of diagnostic tools showed that a substantial number of probable cases, were in fact other infectious diseases (see Table 3). The interaction between HIV and Mpox virus deserves a particular comment. It is widely accepted that the overlap between both infections (and other STI's) is mainly due to the sharing of similar risk factors to acquire them and could not be solely explained by a direct interaction between both diseases.26 Besides this, in spite of the relative low prevalence of HIV infection found, we detected one new HIV case in our series. Of note, some acute HIV-1 and Mpox virus coinfection have been reported.27–30 This emphasizes the need for HIV screening (including acute infection with RNA or p24 protein detection) screening among this population, which may provide high yields of positive results of previously unknown infections.

Apart from the low number of participants included – obviously limiting its external validity –, our study has some limitations. Due to the geographical extension and heterogeneous reality of the study area, some logistic constrains could have restrained the diagnostic process and lead to an underestimation of Mpox incidence. In two suspected cases (eventually classified as “discarded”), anal swabs could not be collected due to logistical constraints. The diagnostic of Mpox could not been roll out on them.

As a conclusion, our study evidences that Mpox could adopt different epidemiological patterns depending on social, geographical and sanitary health resources and needs a wider perspective beyond the most at risk populations. Primary Care physicians are the firs-step attendants in suburban or rural areas and among those patients which do not fit with the epidemiological profile of any given epidemic outbreak. Therefore, in the context of an infectious outbreak Primary Care professionals should maintain a high degree of suspicion, receive timely training, increase clinical support and have easy access to laboratory tests as those used in the checkpoints and STI's clinics,31 and stablish an operational coordination with Public Health officials or other referral professionals. Without this broader approach, Mpox could be quartered in areas with socio-economic or sanitary deficiencies and be easily unnoticed, under-diagnosed or underreported. All these reflections are extensive to any epidemic outbreak in the coming years.

- •

Mpox disease is highly contagious by contact, with multiple cases detected outside endemic areas, mainly in MSM population, which is why it is important to know how this outbreak affects the health system to create protocols and train personnel for its detection.

- •

It is not only the MSM population that can suffer from the disease, cases have also been described in the heterosexual population, which must also be screened in case of compatible symptoms and lesions. Training on the detection of these cases should not only be focused on STI clinics or checkpoints but also on Primary Care centers that have the greatest reach to the susceptible population, mainly in areas where there are no specialized centers.

- •

It shows an idea of how Primary Care can serve as the first step for case detection regardless of sexual behavior or sexual orientation. The good relationship between Primary Care, STI clinics or checkpoints and the public health system is key for prompt action in unexpected outbreaks.

All data were collected from the routine electronic clinical records, anonymized for analysis purposes so that researchers had no access to information that would identify participants. Moreover, a written informed consent was obtained from all them.

FundingThe article has not received any specific funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors state no conflict of interest are perceived, real or potential.