The main underlying etiologies of steatotic liver disease are metabolic syndrome and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD). When both conditions coexist, one of the two conditions predominates, and the other serves as a cofactor. The spectrum of liver damage secondary to Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and ALD ranges from steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. When these entities are associated, it is a synergistic damage and is known as dual damage because of the combined damage of risky alcohol consumption in a person with MASLD, which is known as Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-associated steatotic liver disease (MetALD) [2]. We adopt the definitions of MASLD, MetALD and ALD provided by the multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature by Rinella et al. [2] as follows: MASLD is a form of steatotic liver disease characterized by the presence of hepatic steatosis in individuals with at least one cardiometabolic risk factor, such as overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or hypertension, in the absence of significant alcohol intake or other competing causes of liver fat accumulation. MetALD is a steatotic liver disease occurring in individuals who have both metabolic risk factors (as in MASLD) and alcohol consumption above the threshold considered compatible with MASLD (≥20 g/day in females and ≥30 g/day in males) but below levels typically associated with classical alcohol-related liver disease. ALD is a liver injury caused by chronic, excessive alcohol consumption (≥50 g/day in females and ≥60 g/day in males), encompassing a spectrum of histological and clinical entities including simple steatosis, steatohepatitis, progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Imbalance in fatty acid synthesis and β-oxidation are common pathways in both diseases leading to steatosis. In MASLD, steatosis is due to lipid accumulation, whereas in ALD, it is due to direct ethanol toxicity in hepatocytes [3,4]. There is no safe limit for alcohol consumption, and alcohol intake is associated with an increased risk of liver disease progression, including HCC [5]. The prevalence of MASLD has reached almost 24% in the Western population [6]. However, in specific sub-populations, its prevalence is significantly higher. For example, in subjects with grade 3 obesity, it ranges from 75% to 92%, while the prevalence in patients with type 2 diabetes is estimated at 60% to 70% [7]. In addition, ethnic differences in the prevalence of MASLD have been reported. Hispanic Americans have the highest prevalence at 45% [8]. Individuals of Mexican ancestry have the highest prevalence (33%), followed by Latinos of Puerto Rican origin (18%) and those of Dominican origin (16%) [9]. Another study showed that people of Mexican ancestry have the highest prevalence of MASLD (22%), followed by Central Americans (21%), South Americans(17.8%), Cubans (16.5%), Puerto Ricans (15.8%), and Dominicans (15%) [10]. On the other hand, ALD is one of the leading causes of chronic liver disease in Latin America. Alcohol has been reported to be the primary etiology of cirrhosis in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru [11,12]. The Mexican population has inherited specific alleles from different races, predominantly Caucasian, Amerindian, and African, that predispose to liver damage due to alcohol consumption. Based on current data, there is a particular genetic profile that may explain the epidemiological and clinical manifestations of alcohol-related liver disease [13]. In patients with ALD cirrhosis, up to 33% are overweight or obese [14]. The concept of MetALD is recent; there are not enough epidemiological data that explore this group of patients. The relevance of this group lies in their potential for a higher risk of developing steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis, which may occur in a shorter timeframe. Therefore, it is essential to have information on this population in Mexico.

This study aims to assess the prevalence and severity of steatosis and liver fibrosis in the Mexican population to determine the frequency and stage of MASLD, ALD, and MetALD.

2Materials and MethodsProlective, cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study. Subjects who came as donors to our center's blood bank from June 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022, who were perceived by themselves to be healthy, and who agreed to participate in the study after signing informed consent, were recruited. Subjects older than 18 years, any gender, body mass index (BMI) ≥ 18.5, and who signed informed consent were included. Subjects with pre-existing chronic disease, liver disease, or cancer of any type were excluded. Those who did not attend for liver elastography or who were seropositive for hepatitis B virus and/or hepatitis C virus were eliminated.

2.1ProceduresThe AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) and DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition) questionnaires were applied to all subjects to evaluate alcohol use disorder (AUD) (risky, low and moderate), also the pattern of alcohol consumption (low, moderate and risky), weight and height were measured, and the BMI was calculated, Blood samples were taken to determine biochemical variables (blood chemistry and lipid profile), to estimate the grade of steatosis and liver fibrosis, vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) was performed, the equipment used was FibroScan® 502 Touch. Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) is a measurement of liver fat content performed using the FibroScan device, which assesses ultrasound wave absorption. The score, expressed in decibels per meter (dB/m), indicates the amount of fat in the liver, with higher scores corresponding to greater steatosis or fatty liver. A kilopascal (kPa) is a unit of pressure equal to 1,000 pascals (Pa) and is part of the International System of Units (SI). In the context of a FibroScan, kPa is a unit of measurement for liver stiffness, indicating the degree of scarring (fibrosis) in the liver. A higher kPa value signifies increased liver stiffness, correlating directly with more severe liver scarring and a greater risk of cirrhosis.

We defined the cutoff points for detecting steatosis and fibrosis according to the values established by the equipment supplier (FibroScan® 502 Touch). We used the NASH/NAFLD values for MASLD (steatosis: S1 294-310 dB/m, S2 310-331 dB/m, S3 >331 dB/m; fibrosis: F0-F1 <8.2 kPa, F2 8.2-9.7 kPa, F3 9.7-13.6 kPa, F4 >13.6 kPa), Alcohol for ALD (steatosis: S1 248-268 dB/m, S2 268-280 dB/m, S3 >280 dB/m; fibrosis: F0 <7 kPa, F1 7-9 kPa, F2 9-12.1 kPa, F3 12.1-18.6 kPa, F4 >18.6 kPa), and Multi-etiology for MetALD (steatosis S1 248-268 dB/m, S2 268-280 dB/m, S3 >280 kPa; fibrosis: F0 <6.5 kPa, F1 6.5-7.2 kPa, F2 7.2-9.6 kPa, F3 9.6-14.5 kPa, F4 >14.5 kPa).

The subjects were classified into one of four groups based on liver elastography (VCTE) and AUD punctuation, as well as alcohol consumption patterns: healthy subjects (HS), ALD, MASLD, and MetALD.

2.2Statistical analysisContinuous variables are presented as means, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and categorical data are presented as proportions and percentages. We performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the means of groups HS, ALD, MASLD, and MetALD. Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were used to calculate differences between groups. The chi-square test was used to assess the association between gender and patterns of alcohol consumption. All statistical analyses were conducted with the IBM SPSS statistical package, version 26. Significance in all tests was set at a p-value of 0.05. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for each prevalence using the normal approximation to the binomial distribution. A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the minimum detectable effect size with 80% power (α = 0.05) given the sample sizes of each group, and to estimate the sample sizes required for a confirmatory study with specified absolute error margins.

2.3Ethical considerationsNo invasive interventions were performed on the subjects. All participants were asked to complete an informed consent form, and their personal data were treated with absolute confidentiality.

The project was approved by the ethics and research committees with the number DI/21/310/03/48. The confidentiality of the donors was respected at all times, and their data were not published at any time.

3ResultsData from 324 blood donors were collected. After excluding subjects with incomplete measurements, for the final analysis three hundred nine subjects, 135 females (43%) and 174 males (56%), average age 35.5 (28.3–39.29), were classified according to steatosis grade by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP, measured by VCTE) and alcohol consumption pattern into one of four groups described above: 97 (31.4%) HS; 54 (17.5%) ALD, 140 (45.3%) MASLD, and 18 (5.8%) MetALD. All other demographic variables and the mean difference between groups are shown in Table 1. The prevalence of MASLD in our sample was 45.3% (95% CI: 39.7–50.9), ALD 17.5% (13.3–21.7), MetALD 5.8% (3.2–8.4), and HS 31.4% (26.2–36.6). These confidence intervals demonstrate the precision of our estimations and underscore that MetALD, although less frequent, was present in approximately 6% of participants. The precision of MetALD in our study population was ± 2.6. Increasing the absolute precision to ±2, a sample of 525 participants would be required, and for ±1, a sample of 2,099 would be required. With the current group sizes, the study has 80% power (α=0.05) to detect moderate-to-large differences (Cohen’s d = 0.37–0.45); for comparisons between medium and large groups, the effect size increases to 0.7-0.76 when comparing MetALD as the smallest group to others.

ANOVA test for control ALD, MASLD, and MetALD groups for Demographic characteristics.

a = Healthy subjects vs ALD; b= Healthy subjects vs MASLD; c= Healthy subjects vs MetALD; d= ALD vs MASLD; e= ALD vs MetALD; f= MASLD vs MetALD.

ALD = Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BMI = Body Mass Index; CAP = controlled attenuation parameter; gr = grams; Kpa = kilopascals; MASLD= Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Liver Disease; MetALD = Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-associated steatotic liver disease.

The AUDIT score was < 8, indicating that alcohol consumption is safe in the healthy (2.35 {1.95- 2.76}) and in the MASLD groups (2.39 {2.06- 2.72}), while higher scores were in the ALD groups (10.59 {9.72-11.47}) and MetALD groups (9.28 {8.04-10.52}).

However, the average number of grams of alcohol consumed per occasion was higher in MetALD than in those in the ALD group: 221.16 (136.87-305.45) and 180.24 (103.72-256.76), respectively, with no statistical difference (Table 1). There was also higher consumption in grams per occasion in MetALD and ALD than in the HS and MASLD groups.

The AUDIT with a value > 8 indicated a risky consumption of alcohol, which is high in the ALD and MetALD groups; in terms of the grams of alcohol consumed per occasion, we found that these groups consumed alcohol over 13 standard drinks/occasion. Regarding the patterns of alcohol consumption, we divide them into risky consumption (AUDIT > 8, with negative DSM-5), low alcohol use disorder (AUD) (AUDIT > 8, with positive DSM-5: 1 question), and moderate AUD (AUDIT > 8, with positive DSM-5 to plus 3). We found in the ALD group that 37% of the subjects had moderate AUD, being a population of youngsters (age 35.5 years), while in the MetALD group, 72% of the subjects had risky consumption with an average age of 33.8 years. This indicates that subjects in the ALD group have advanced problems with their alcohol consumption.

When comparing consumption patterns according to DSM-5, in the ALD groups, we found 31.48% with risky consumption, 31.48% with low AUD, and 37.04% with moderate AUD. In the risky group, 23.50% were women and 76.50% men, the same proportion was found in subjects with low AUD. In individuals with moderate AUD, 85% were men and 15% were women (Table 2).

Alcohol consumption distribution among gender.

Table 2 compares the consumption patterns for ALD and MetALD groups by gender. In both groups, there are more men than women. In the ALD group, there is more moderate AUD than risk consumption and low AUD in men. No moderate AUD on MetALD is observed. There was no association with the chi-square test p = .754 for ALD and p = .952 for MetALD.

ALD = Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; MetALD = Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-associated steatotic liver disease.

On the other hand, when applying DSM-5 to subjects with MetALD, 72.22% had risky consumption, 27.78% had low AUD, and no individual had moderate AUD. In addition, 38.50% of the subjects with MetALD and risk consumption were women, and 61.50% were men, while 40% of those with low AUD were women, and 60% were men.

The grams of alcohol consumed per occasion were, in decreasing order: 221.16 (136.87- 305.45) in MetALD, 180.24 (103.72- 256.76) in ALD, 41.16 (35.45- 46.88) in MASLD, and 43.65 (34.44- 52.85) in the control group. This reflects that the study population that does not have risky alcohol consumption consumes alcohol in moderate amounts.

The average BMI was out of range in all four groups: 26.8 (25.91-27.7) in HS and 26.41 (25.43-27.39) in ALD. We found obesity rates in MASLD and MetALD to be 30.78% (29.9-31.67%) and 33.16% (31.09-35.23%), respectively. As expected, BMI was larger in MetALD and MASLD and lower in ALD and HS; these differences were statistically significant, as shown in the one-way ANOVA analysis (see Table 1). In the post hoc analysis, statistically significant differences were found between the HS, ALD, MASLD, and MetALD groups.

MASLD has abnormal glucose levels, which were statistically higher in MASLD and MetALD than in HS. There were also statistical differences in triglyceride concentrations in ALD, MASLD, and MetALD compared to HS, and HDL values were higher in the ALD group compared to MASLD and MetALD.

The one-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in ALT, AST, GGT, glucose, uric acid, HDL, and triglycerides (see Table 3). The pairwise comparison reveals statistically significantly higher ALT values in the ALD, MASLD, and MetALD groups compared to the HS group. In contrast, AST values were higher in MetALD than in HS. GGT concentrations were higher in ALD and MetALD than in HS, while GGT in MetALD was higher than in MASLD.

ANOVA test for control ALD, MASLD, and MetALD groups for biochemical, liver functioning, and alcohol consumption variables.

a = Healthy subjects vs ALD b= Healthy subjects vs MASLD; c= Healthy subjects vs MetALD; d= ALD vs MASLD; e= ALD vs MetALD; f= MASLD vs MetALD.

ALD = Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; GGT = gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; HDL = High-density lipoprotein; LDL = Low-density lipoprotein; MASLD= Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Liver Disease; MetALD = Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-associated steatotic liver disease; Tg = triglycerides.

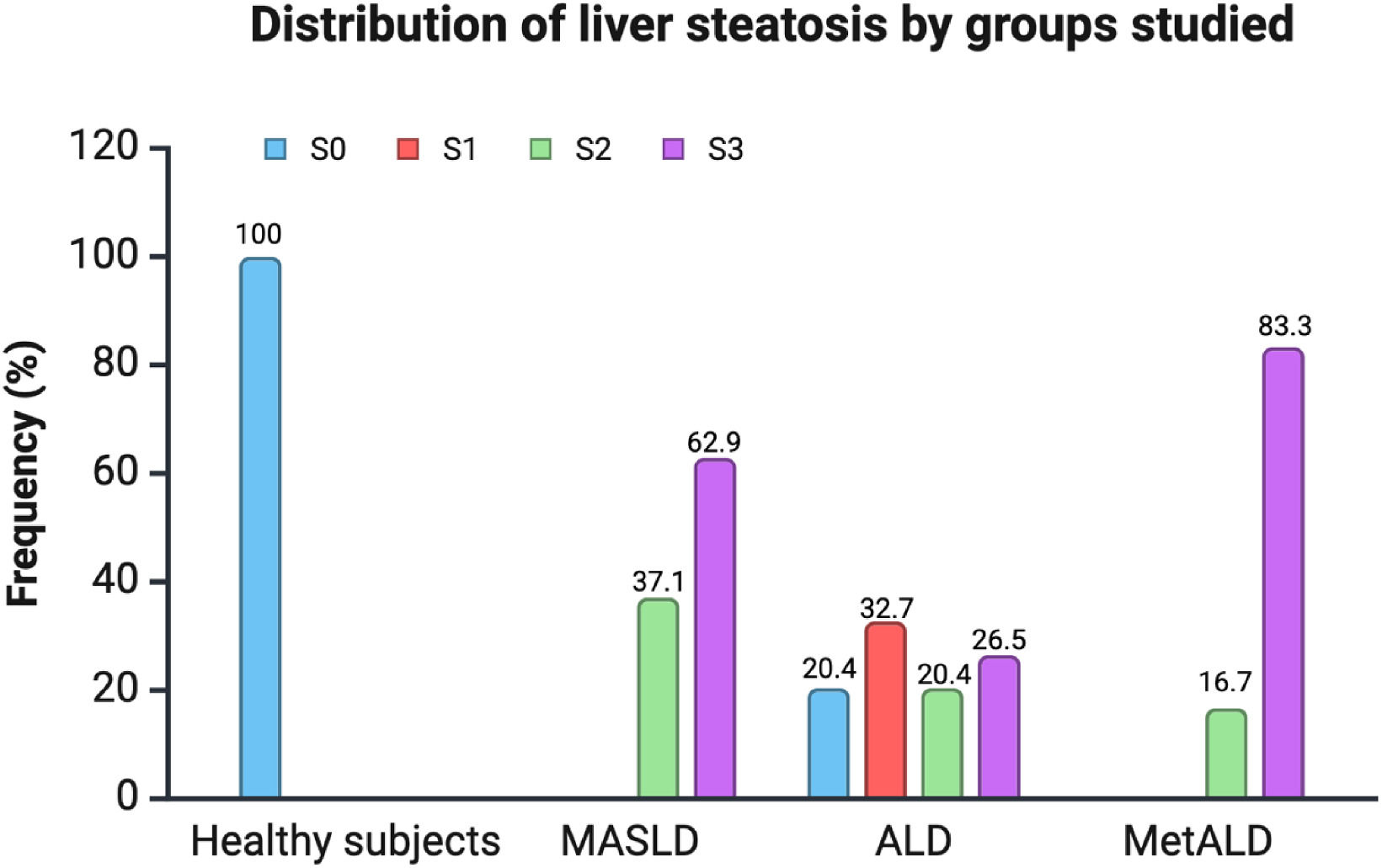

The CAP score evaluated steatosis. Measures were statistically significant (p < 0.001) in all pairwise comparisons except for MASLD vs. MetALD, where scores were similar. Grade 3 steatosis was observed in the MASLD and MetALD groups.

Liver stiffness scores were measured in kilopascals (kPa), showing average higher values in the MetALD group (p < 0.001); statistical differences were between HS vs. MASLD and MetALD, as well as MetALD vs ALD and MASLD (Table 1, Fig. 2).

4DiscussionThe results of this study are interesting. The data were obtained from blood bank donors from the Mexican population, who consider themselves “healthy” and therefore come to donate, and are of an age considered young (36 ± 12.6 years). We found that 70% of these subjects have some degree of liver steatosis, and the group perceived as healthy, with no liver steatosis, is only 31.40%. Overweight and obesity is a characteristic in the four groups, so perhaps considering the “healthy” group as truly healthy could be in doubt, since it is overweight considering this group with an average BMI of 26.8 (25.91–27.7), but without alcohol consumption, nor any grade of steatosis or fibrosis, that is why we have called it the healthy control group. On the other hand, the BMI of the other three groups are different, being statistically significant, the group that consumes alcohol with a BMI 26.41 (25.43–27.39) but with some grade of steatosis and/or fibrosis, the MASLD group with a BMI of 30.78 (29.9–31.67) which corresponds to grade I obesity and the MetALD group with BMI 33.16 (31.09–35.23). By comparing this finding with the results of the most recent National Health and Nutrition Survey, we see that only 27.6% of the Mexican population has an adequate weight for their height, while obesity has overtaken overweight as the most frequent state of malnutrition (36.7% vs 35.7%) [15]. Thus, the presence and grade of steatosis are different in each group, the healthy group without steatosis, the patients who consume alcohol with a grade 3 steatosis of 26.5%, the MASLD group with grade 3 steatosis up to 62.9% and the most affected group is the MetALD group with grade 3 steatosis up to 83.5%, this being explained by the double damage to the liver (obesity and risky alcohol consumption) (Fig. 1, and Table 3).

In the ALD group, the male gender predominated, whereas in the healthy control and MASLD groups, the male-to-female ratio was similar at 1:1. However, the female gender predominated in the MetALD group. The National Survey on Drug, Alcohol, and Tobacco Consumption (ENCODAT) conducted in our country in 2016 showed that younger women consume more alcohol and start consuming alcohol at younger ages, supporting evidence from other countries noting that liver disease due to alcohol consumption in women has increased up to 50% compared to 30% in men [16]. Our findings suggest that women may be at greater risk of developing liver damage when metabolic factors and risky alcohol consumption are combined due to several factors, including women's susceptibility to liver damage due to fewer alcohol metabolizing enzymes, fat distribution, and the presence of estrogen.

Inflammation, as measured by liver enzymes (AST and ALT), differs among the groups. It is normal in the healthy group and elevated in the other three groups, with a higher level in the MetALD group. This is likely accompanied by higher interleukins, cytokines, and oxidative stress, which would be worth measuring. The absence of these measurements is a weakness of our study.

Regarding the findings of liver fibrosis, as expected, most of the subjects did not have fibrosis. When comparing the groups, important findings were observed in those with some degree of fibrosis. In the ALD group, F1, F2, and F3 were found in order of decreasing frequency, and F4 was not detected. Subjects with F4 were found in the groups with metabolic dysfunction. The highest proportion of subjects with F4 was found in the MetALD group (16.7% vs. 2.9% in MASLD). In MASLD, F2 was the most prevalent grade of fibrosis, followed by F1 and F3 in equal numbers. Finally, in MetALD, F4 was the most frequent fibrosis grade, while F2 and F3 were equally prevalent; no subjects had F1. This finding is relevant because it has traditionally been postulated that dual damage affects the liver in a more intense and accelerated manner, and this study supports it. We found that individuals with MASLD have the highest steatosis, and the average fibrosis is more advanced in subjects with MetALD. This reinforces the emerging serious public health problem with the increasing prevalence of overweight/obesity and alcohol consumption in our population, which increases the risk of developing advanced chronic liver disease earlier and will eventually lead to increased demand for health services.

When analyzing the biochemical parameters included as diagnostic criteria for MASLD, we found that the group with metabolic dysfunction is the only one that included subjects with abnormal fasting glucose. However, the highest concentrations of cholesterol and triglycerides were found in the MetALD group. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol values are found to be lower in the MetALD group. This is consistent with the evidence pointing to insulin resistance as a fundamental pathophysiological factor in the development of MASLD, [17], and it demonstrates a direct proportional relationship between increased alcohol consumption and serum cholesterol levels, specifically low-density lipoproteins, and triglycerides [18]. It should be noted that the MetALD group was the one that showed the highest grade of elevation of aminotransferases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, which objectively shows the grade of damage that these subjects develop. All these biochemical parameters, except the total cholesterol value, showed statistical significance.

The age of onset of alcohol consumption was similar in all groups, which is earlier than reaching the age of adulthood, including the control group. However, the years of consumption are lower in the MetALD group, which again highlights that liver damage occurs more intensely and is accelerated in subjects with simultaneous metabolic dysfunction and risky alcohol consumption. Risky alcohol consumption at younger ages increases the time of toxic exposure, which favors liver damage and its progression to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition, the MetALD group has a higher number of grams of alcohol consumed compared to the group with exclusive alcohol damage. Both groups have risky alcohol consumption identified by AUDIT.

To date, we have not found any Mexican studies that evaluate the prevalence and characteristics of individuals with MetALD; therefore, this work sets a precedent. Our work has the strength of studying a population without chronic liver diseases or other diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, which could represent a confounding factor when estimating the grade of steatosis and fibrosis. We, therefore, exclusively included people who perceived themselves to be healthy, although most were identified as having an inadequate weight for their height. We understand that one limitation of our study is that our sample represents a cohort rather than a broader population in our country. However, it is a precedent considering that we studied subjects who perceive themselves as healthy. We suggest publications that include a larger number of centers and subjects to establish a broader picture of dual liver damage in Mexico.

5ConclusionsOur study demonstrated a prevalence of 45.3%, 17.5%, and 5.8% for MASLD, ALD, and MetALD, respectively. Although MetALD has the lowest prevalence compared to MASLD and ALD, it has the highest grade of steatosis and liver fibrosis. High BMI and risky alcohol consumption were associated with the severity of liver disease. This reinforces the emerging serious public health problem with the increasing prevalence of overweight/obesity and alcohol consumption in our population, which increases the risk of developing advanced chronic liver disease earlier and will eventually lead to increased demand for health services.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsJELV: Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. ADSV: Data curation, formal analysis. GGR: Conceptualization, data curation. OMG: Data curation. MFHT: Conceptualization, data curation. DMO: Data collection. CHS: Data collection. MMC: Data curation. SSV: Data collection. MALP: Data collection. DMOA: Data collection. AHB: Data collection. MHS: Data collection. YLBR: Data curation. JLPH: Conceptualization, writing – review & editing.

None.