One-carbon metabolism (OCM) encompasses a network of metabolic pathways providing one-carbon units (methyl groups) for cellular methylation reactions and is essential for synthesizing DNA, polyamines, amino acids, creatine, and phospholipids [1,2]. OCM also plays an important role in cellular energy homeostasis, and alterations have been associated with the development of obesity and other metabolic diseases [3,4]. Raised homocysteine levels have been associated with cardiovascular morbidity and type 2 diabetes, possibly reflecting a change in the activity of the methionine cycle and the transsulfuration pathway [5]. Changes in the expression levels of key enzymes such as methionine adenosyltransferase, cystathionine beta-synthase, and cystathionine gamma-lyase as well as the synthesis of metabolites such as S-adenosylmethionine and glutathione have been reported in diet-induced steatotic mouse models [6]. It is likely that changes in OCM are also implicated in the development of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [2].

Disruptions in the OCM pathways can lead to imbalances in the availability of methyl donors, impacting DNA methylation and protein modification. Dysregulation of the methionine cycle and the transsulfuration pathway are associated with insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation, all believed to be implicated in MASLD development. In addition, choline and S-adenosylmethionine are substrates for the formation of phosphatidylcholine [7,8], which is involved in very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) assembly and secretion from the liver [9]. Impaired phosphatidylcholine secretion from the liver affects lipid metabolism and leads to the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides [10]. Mouse models with reduced expression of enzymes involved in the regulation of S-adenosylmethionine, and subsequently phosphatidylcholine, show increased susceptibility to the development of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis [11–13]. Decreased mRNA expression of these enzymes have been linked to the histopathological severity in patients with steatotic liver disease [14].

Oxidative stress plays a key role in the development of MASLD and contributes to the progression from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis[15–17] and is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction[18] as well as an imbalance between the production and detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [19]. In MASLD, increased production of glutathione may ameliorate oxidative stress [20].

The association between alterations in OCM in plasma and the liver and the possible changes in metabolite profile following treatment with Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP1-RAs) may provide valuable insights into the disease mechanisms implicated in MASLD development and progression. This study evaluates MASLD-associated alterations in OCM in both plasma and liver from patients with histologically verified MASLD compared to healthy controls as well as a MASLD mouse model subjected to treatment with the GLP1-RA semaglutide compared to vehicle or chow.

2Materials and Methods2.1Patients with MASLD and healthy controlsPatients were included in a prospective cohort study of biomarkers in MASLD. The study is approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-17,029,039) and adheres to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided their informed consent. The study is ongoing with a planned sample size of 1000 patients, and this paper includes patients and controls who were included from January 2017 to December 2022. Patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic at the Gastro Unit, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre and healthy controls via online advertising. Patients and controls were evaluated clinically and with routine blood tests (including liver and metabolic assessments), Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4), and Transient Elastography (TE). The healthy controls had no history of liver disease, type 2 diabetes, or other diseases. All patients with MASLD and a subgroup of healthy controls underwent a liver biopsy. The following data were recorded for all participants: demographics, body mass index (BMI), medical history, TE, FIB-4, and laboratory tests: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, creatinine, total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL), triglycerides (TG), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), platelets, hemoglobin, white blood cell count (WBC) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Fasting blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and placed in wet ice before centrifugation at 2500 G for 10 min at 4 °C. Plasma was stored at −80 °C until analyses.

Two expert pathologists evaluated the liver biopsies, which were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE), Picro Sirius Red (PSR) and immunostained for p62 (described in supplementary materials). MASLD was diagnosed based on steatosis, inflammation, ballooning, and fibrosis [21]. Significant fibrosis was defined as a fibrosis score ≥ 2. MASH was defined as presence of steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation.

2.2Targeted metabolomics (human samples)The plasma concentration of the OCM metabolites were analyzed in 100 patients with MASLD and 50 healthy controls at the Bevital Laboratory, Bergen, Norway (www.bevital.no). According to pathway, the following metabolites were quantified: the Methionine cycle: methionine, homocysteine; Folate cycle: folate, cobalamin, riboflavin; Choline oxidation pathway: choline, betaine, dimethylglycine; Transsulfuration pathway: serine, cystathionine, cysteine, α-hydroxybutyrate, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; and Glutathione pathway: glycine, glutamate. We also calculated the GSG index, a proxy marker of glutathione synthesis (glutamate/ [serine+glycine]), as an indicator of oxidative stress [22].

Plasma cobalamin (vitamin B12) and folate (vitamin B9) concentrations were determined by microbiological assays based on a colistin sulfate-resistant strain of Lactobacillus leichmannii and a chloramphenicol-resistant strain of Lactobacillus casei [23,24]. The B6 vitamin form, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, and riboflavin (vitamin B2) as well as choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [25]. Total homocysteine, a functional indicator of folate and cobalamin status, cysteine, methionine, serine, glycine, cystathionine, glutamate and α-hydroxybutyrate were analyzed using gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (GC–MS/MS). The assays were adapted to a microtiter plate format and carried out by a robotic workstation. The within-day coefficient of variation (CV) was 4 % for cobalamin and folate, 3 % for pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, 6 % for riboflavin and 1 % for total homocysteine, and ranged from 1 % to 2 % for cysteine, methionine, serine, glycine, cystathionine, glutamate and alpha-hydroxybutyrate and from 3 % to 6 % for choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine. The between-day CV was 5 % for both cobalamin and folate and ranged from 6 % to 8 % for pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, and riboflavin, 2 % for total homocysteine, and 2 % to 4 % for cysteine, methionine, serine, glycine, cystathionine, glutamate and α-hydroxybutyrate, and 3 % to 6 % for choline, betaine and dimethylglycine.

2.3Untargeted transcriptomics (human samples)Bulk RNA sequencing of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) liver biopsies was performed to analyze the expression of enzymes in the following OCM pathways: Methionine cycle (methionine adenosyltransferase 1A, MAT1A; methionine adenosyltransferase 2A, MAT2A; methionine adenosyltransferase 2B, MAT2B; glycine N-methyltransferase, GNMT; adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase, AHCY), Folate cycle (serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1, SHMT1; serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2, SHMT2; methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, MTHFR; methionine synthase, MTR), Choline oxidation (choline dehydrogenase, CHDH; aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family member, ALDH7A1; betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase, BHMT; betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase 2, BHMT2; dimethylglycine dehydrogenase, DMGDH; pipecolic acid and sarcosine oxidase, PIPOX; sarcosine dehydrogenase, SARDH), Transsulfuration pathway (cystathionine beta-synthase, CBS; cystathionine gamma-lyase, CTH), cysteine oxidation (Cysteine dioxygenase 1, CDO1; cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase, CSAD), Glutathione pathway, glutamate-cysteine ligase C, GCLC; glutamate-cysteine ligase M, GCLM; glutathione synthetase, GSS; glutathione-disulfide reductase, GSR; glutathione peroxidase 1, GPX1; glutathione peroxidase 2, GPX2; glutathione peroxidase 3, GPX3; glutathione peroxidase 4, GPX4).

RNA was extracted from FFPE liver biopsies using the RNeasy FFPE Kit. RNA quality was assessed using the Fragment Analyzer System, with a focus on samples with DV200 above 30 %. Strand-specific libraries were prepared, and coding regions of the transcriptome were captured using the TruSeq RNA Exome kit. Sequencing was performed with the Illumina NovaSeq platform, yielding single-end 75 bp reads, which were then aligned to the human genome (GRCh38) using STAR, and quantified with Salmon. Quality control was conducted using FastQC, Picard, and STAR, consolidated by MultiQC. Gene expression associations were evaluated via DESeq2’s logistic regression, which uses a negative binomial model with inclusion of batch effects and sex as covariates and statistical significance determined by Wald test.

2.4Mouse modelsMale C57BL/6JRj mice were fed the Gubra Amylin MASH diet with 40 % fat, 22 % fructose, and 2 % cholesterol for 33 weeks prior to study start [26]. All mice treated with the diet developed obesity and had a steatosis score ≥2 and fibrosis stage ≥1 based on collagen1a1 (Col1a1) quantification % fractional area. Mice were randomized to 12 weeks of treatment with vehicle (n = 16) or subcutaneous semaglutide 30 nmol/kg/day (n = 16). Age-matched chow-fed mice were used as controls (n = 6). At baseline steatohepatitis was confirmed histologically by image analysis in DIO-MASH mice by increased relative and total levels of steatosis and inflammation based on Gal-3 deposition. The fibrotic phenotype was confirmed by increased hepatic α−1 chain of type I collagen and alpha-smooth muscle actin compared with chow vehicle, supporting the translatability to human disease [27]. After 12 weeks, the mice were fasted, and samples (blood and liver tissue) were collected and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Plasma and liver tissue underwent untargeted metabolomics using ultra high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS). The analyses were conducted by Metabolon Inc. (Durham, USA) using standardized published methods [28,29]. A total of 976 (886 named and 110 unnamed) metabolites were identified from the liver tissue, while 898 (777 named and 121 unnamed) metabolites were identified in plasma. The instrument variability was evaluated by calculating the median relative standard deviation (RSD) for the internal standards (3 % liver and 5 % plasma) The process variability was estimated by calculating the median RSD for all metabolites (i.e., non-instrument standards) in technical replicates created from all samples (8 % liver and 9 % plasma). All were within the vendors quality control specifications.

Bulk RNA sequencing was performed on liver tissue samples from DIO-MASH and chow-fed mice. RNA samples were used to generate cDNA libraries with the TruSeq Stranded mRNA preparation kit. These libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform, producing paired-end reads of 50 base pairs. The resulting reads were aligned to the mouse genome (mm10) using the STAR aligner (v2.4) and quantified with RSEM (v1.2.14). Raw RNA-seq counts were then normalized with edgeR (v3.24.3) using the TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) method to correct for library size differences. Differential gene expression was analyzed with edgeR (v3.24.3), and statistical significance was determined using the quasi-likelihood F-test.

2.5Statistical analysesContinuous data are presented as medians with interquartile range (p25–p75 intervals). Groups were compared with Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Correlations between plasma metabolites and histological features were assessed with Pearson’s or partial Spearman’s correlation adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). When Pearson’s correlation was used, logarithmic transformation was applied. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.2.2.

3Results3.1Patients with masld vs healthy controlsPatients with MASLD (n = 100) and healthy controls (n = 50) were matched for age and sex; 51 % of patients had type 2 diabetes, 44 % had hypertension, and 64 % had dyslipidemia (Table 1). Patients with MASLD had a higher BMI, liver function tests, and C-reactive protein as well as lower creatinine levels (Table 1). Histological assessment showed that 51 % of patients had no/mild fibrosis and 49 % had significant fibrosis (F2 n = 20, F3 n = 12, F4 n = 17). Twenty-five percent had no inflammation and 75 % had steatohepatitis with steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning.

Characteristics of patients with MASLD and healthy controls, with medians and interquartile range (p25-p75). Groups are compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test, adjusted for age, Body Mass Index (BMI), and sex.

Targeted metabolomics showed that several metabolites differed between MASLD patients and healthy controls. Complementary bulk transcriptomics showed that several enzymes involved in OCM differed between MASLD patients and healthy controls (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table S1, and Supplementary Figure S1). Compared with healthy controls, patients with MASLD showed reduced levels of metabolites in all parts of the OCM except the methionine pathway. As shown in Table 2, reduced metabolites were found in the folate cycle, choline oxidation pathway, the transsulfuration pathway, and glutathione pathway including plasma betaine (29.9 [p25-p75: 24.3–35.7] vs. 37.0 [29.8–41.9] µmol/L, P < 0.001), folate (13.4 [8.7–25.6] vs. 17.5 [12.9–30.4] nmol/L, P = 0.03), serine (99 [93–114] vs. 119 [102–130] µmol/L, P < 0.001), glycine (209 [174–246] vs. 257 [230–287] µmol/L, P < 0.001), and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, which is the active form of vitamin B6 (41.1 [31.5–60.8] vs. 64.1 [55.5–104] nmol/L, P < 0.001). Increased metabolites were only identified for the transsulfuration pathway and glutathione pathway including α-hydroxybutyrate (65.4 [46.4–85.5] vs. 35.1 [28.3–43.4] µmol/L, P < 0.001), cystathionine (0.40, [0.26–0.57] vs. 0.25 [0.20–0.45] µmol/L; P = 0.003), and glutamate (78.2 [62.6–109] vs. 38.9 [30.7–52.0] µmol/L, P < 0.001, Fig. 1C). Accordingly, the GSG index (0.28 [0.19–0.35] vs. 0.11 [0.08–0.14] µmol/L, P < 0.001) was increased.

One-carbon metabolism (OCM) in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Panel A shows summary findings of targeted metabolomics (plasma) and transcriptomics (liver) in analyses of patients with histologically verified MASLD vs healthy controls. Decreased levels/expression in MASLD are indicated in blue, increased levels/expression in red, and green indicates no difference (correction for batch, sex, and multiple testing). Panel B shows alterations in Glutathione pathway for patients with MASLD vs healthy controls, MASLD with steatohepatitis (MASL) vs simple steatosis (MASL), and MASLD with significant (F2-F4) vs no/mild (F0-F1) fibrosis. The bars indicate median values and error bars range (P < 0.001 for all analyses).

Targeted metabolomics in patients with MASLD vs healthy controls, MASLD with F2–4 vs F0–1 fibrosis, and MASLD with steatohepatitis (MASH) vs simple steatosis (MASL). Groups are compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test, adjusted for age, Body Mass Index (BMI), and sex. The relative concentration of metabolites is denoted by a unique color with blue indicating reduced concentration and red an increased concentration.

The RNAseq analyses showed a decrease in hepatic gene expression of several enzymes of the methionine cycle, the transsulfuration pathway, the choline oxidation pathway, and the folate cycle (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table S1, and Supplementary Figure S1). The changes included reduced expression of methionine adenosyltransferase 1A (Log2FC −0.67, P < 0.0001), glycine N-methyltransferase (Log2FC −1.59, P < 0.0001), adenosylhomocysteinase (Log2FC −0.98, P < 0.0001), cystathionine beta-synthase (Log2FC −0.68, P = 0.0007), and cystathionine gamma-lyase (Log2FC −0.55, P = 0.01). Increased gene expression was only observed for enzymes in glutathione metabolism, namely glutathione-disulfide reductase (Log2FC 0.27, P = 0.01) and glutathione peroxidase 2 (Log2FC 1.46, P = 0.0004).

Volcano plots from RNA-seq analyses depicting differential expression of enzymes involved in one-carbon metabolism (OCM) in liver tissue. Panel A compares patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) to healthy controls. Panel B Panel B compares patients with MASLD and advanced fibrosis (F2–F4) to those with mild or no fibrosis (F0–F1). Decreased expression is indicated in blue, increased expression in red, and grey indicates no difference. All analyses include correction for batch, sex, and multiple testing.

Targeted metabolomics comparing MASLD with F2–4 vs F0–1 fibrosis only showed a reduction in pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (37.3 [25.5–50.7] vs 49.8 [36.9–66.7], P = 0.001, Table 2). None of the other the transsulfuration metabolites were reduced. Similar to the comparison between MASLD vs healthy controls, patients with MASLD and F2–4 fibrosis had increased metabolites in the transsulfuration pathway and glutathione pathway including cystathionine (0.43 [0.30–0.90] vs 0.32 [0.24–0.45], P = 0.006), α-hydroxybutyrate (77.7 [48.6–95.6] vs 58.0 [45.8–78.3], P = 0.03), glutamate (95.4 [65.1–112.2] vs 73.9 [59.9–95.3], P = 0.04), and the GSG index (0.30 [0.22–0.40] vs 0.26 [0.19–0.30], P = 0.04). Patients with MASLD and F2–4 also had an increased concentration of choline (8.7 [7.1–10.3] vs 7.2 [6.1–8.6] µmol/L, P = 0.004).

RNAseq analyses showed marked alterations in patients with F2–4 vs F0–1 fibrosis, including reduced expression of enzymes in a large number of OCM enzymes in patients with significant (F2–4) versus mild/no (F0–1) fibrosis (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S1). The changes included reduced expression in patients with significant fibrosis of methionine adenosyltransferase 1A (Log2FC −0.37, P < 0.0001), glycine N-methyltransferase (Log2FC −0.56, P = 0.01), adenosylhomocysteinase (Log2FC −0.28, P = 0.005) and serine‑hydroxymethyltransferase (Log2FC −0.29, P = 0.004). Four of seven enzymes involved in choline oxidation showed decreased expression: aldehyde dehydrogenase-7 family member A1, betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase, dimethylglycine dehydrogenase, pipecolic acid and sarcosine oxidase. Both enzymes in the transsulfuration pathway showed reduced expression: cystathionine beta-synthase (Log2FC −0.30, P = 0.02) and cystathionine gamma-lyase (Log2FC −0.32, P = 0.01). In cysteine oxidation, reduced expression was found for cysteine dioxygenase 1 (Log2FC −0.29, P = 0.0004), glutamate-cysteine ligase C (Log2FC −0.15, P = 0.005), and glutathione peroxidase 4 (Log2FC −0.17, P = 0.02). Only one enzyme, methionine synthase, showed increased expression (Log2FC 0.21, P = 0.006).

3.3Patients with masld and steatohepatitis (MASH) vs simple steatosis (MASL)Metabolomics and transcriptomic analyses of patients with MASH vs MASL only showed minor alterations. One metabolite, glycine, was reduced in MASH vs MASL (202 [173–227] vs. 252 [189–277] µmol/L, P = 0.008). Patients with MASH had increased α-hydroxybutyrate (75.2 [50.0–88.8] vs. 49.8 [40.9–69.4] nmol/L, P = 0.02, Table 2) and glutamate (84.0 [64.5–110.7] vs. 67.8 [51.1–95.4] µmol/L, P = 0.03). Accordingly, the GSG index was increased in MASH (0.29 [0.21–0.40] vs. 0.24 [0.15–0.28], P = 0.004). The RNAseq analyses only reduced expression of methionine adenosyltransferase 1A (Log2FC −0.31, P = 0.04). No other differences between the two groups were observed.

3.4Correlation between RNAseq of liver tissue and p62 area fraction as a marker of oxidative stressAs shown in Supplementary Table S2, post hoc analyses including patients with MASLD, showed a negative correlation between hepatic enzyme activity and p62 area fraction for four of five enzymes in the methionine cycle: Methionine adenosyltransferase 1A (Log2FC −0.07, P = 0.002), methionine adenosyltransferase 2A (Log2FC −0.07, P = 0.03), glycine N-methyltransferase (Log2FC −0.24, P < 0.0001), adenosylhomocysteinase (Log2FC −0.08, P = 0.003). The p62 area fraction was negatively correlated with two enzymes in the choline oxidation pathway, choline dehydrogenase (Log2FC −0.06, P = 0.01) and sarcosine dehydrogenase (Log2FC −0.13, P < 0.0001) as well as one enzyme in the transsulfuration pathway cystathionine beta syntase (Log2FC −0.09, P = 0.001). The only positive correlations were identified in glutathione metabolism: Glutathione-disulfide reductase (Log2FC 0.04, P = 0.004), glutathione peroxidase 1 (Log2FC 0.06, P = 0.005), and glutathione peroxidase 2 (Log2FC 0.16, P = 0.007),

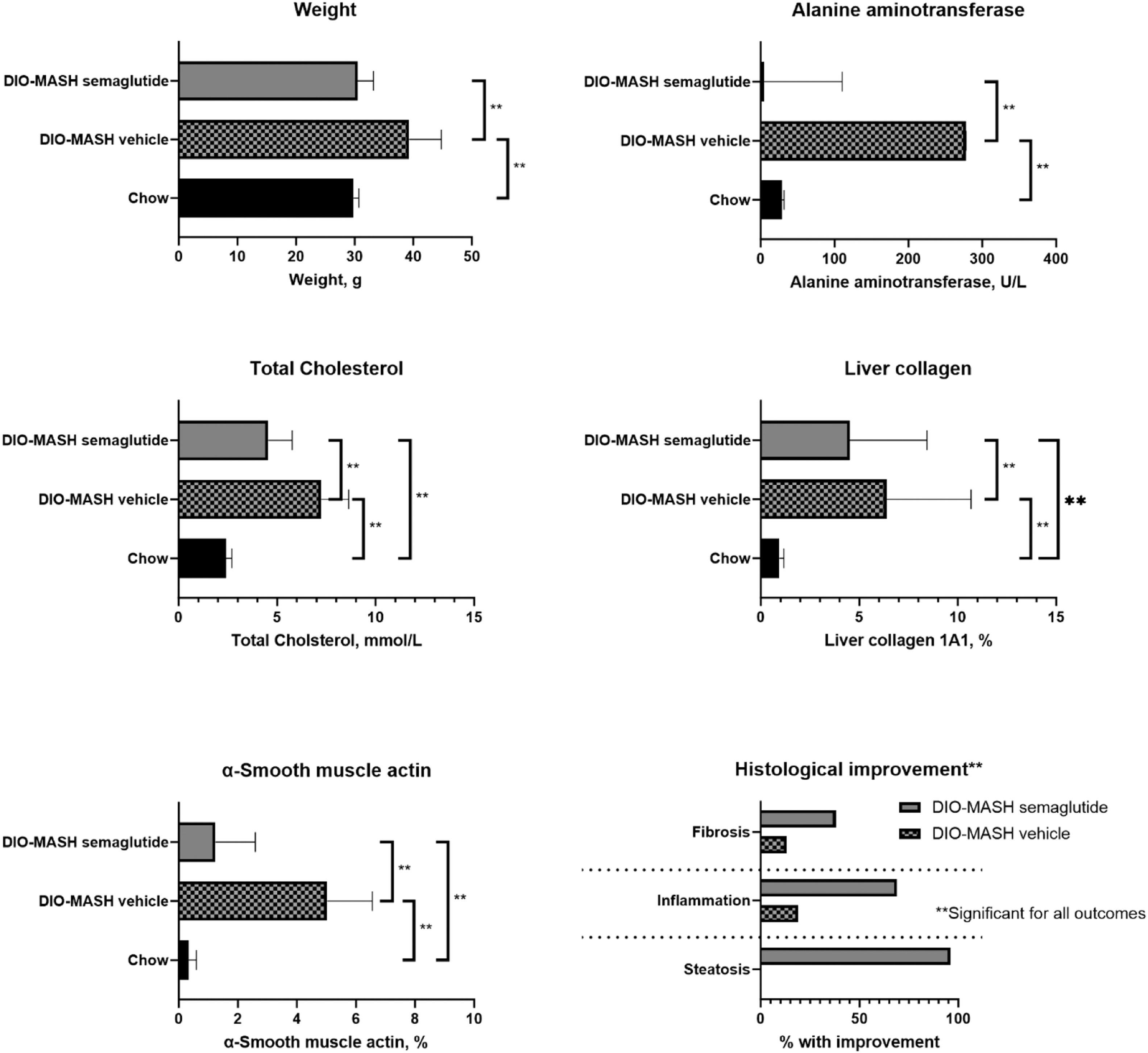

3.5Characteristics of animal modelsCompared with chow, DIO-MASH mice developed higher weight, hepatomegaly, increased hepatic triglycerides, and liver enzymes (Fig. 3). All mice in the DIO-MASH and none in the chow group developed grade 3 steatosis. Fifteen of 16 (96 %) in the DIO-MASH group treated with semaglutide and none in the vehicle or chow group had improved hepatic steatosis after treatment. In the chow group, 1/6 (17 %) had a reduction of lobular inflammation whereas the numbers were 3/16 (19 %) in the DIO-MASH vehicle group and 11/16 (69 %) in the DIO-MASH semaglutide group. Improvement in fibrosis was seen in 2/16 (13 %) in the DIO-MASH vehicle group, 6/16 (38 %) in the DIO-MASH semaglutide group and 0/6 in the chow group (collagen 1a1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin, Fig. 3). After treatment, hepatic fibrosis significantly decreased in DIO-MASH semaglutide vs. vehicle (3.45 %, 0.82–4.70 % vs. 2.15 %, 0.38–5.76 %, P < 0.05).

Animal models of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). The analyses included DIO-MASH mice randomized to semaglutide (n = 16) vs vehicle (n = 16) for 12 weeks and chow controls (n = 6). The figures show body weight, p-alanine aminotransferase, total p-cholesterol and hepatic α-Smooth muscle actin, collagen 1A1 as well as histological changes (inflammation and fibrosis) after 12 weeks. Data are presented as median and range or % with histological improvement. Groups are compared with Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05.

The untargeted analyses of metabolites in the liver included a higher number of metabolites than in plasma (Table 3). Overall, the analyses showed that compared to chow, DIO-MASH mice showed decreased abundance of several metabolites in the liver while plasma levels largely remained unaltered or increased (Table 3). Compared to chow, DIO-MASH mice had decreased levels of the following metabolites in the liver: methionine (FC 0.60; P = 0.005), S-adenosyl homocysteine (FC 0.52; P = 0.002), and homocysteine (FC 0.31, P = 0.002), folate (FC 0.35; P = 0.007), serine (FC 0.64; P = 0.01), glycine (FC 0.57; P = 0.002), riboflavin (FC 0.57; P = 0.002), sarcosine (FC 0.63; P = 0.002), cystathionine (FC 0.63; P = 0.02), pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (FC 0.67; P = 0.01), hypotaurine (FC 0.56; P = 0.02), and glutamate (FC 0.68; P = 0.02).

Differential expression of OCM metabolites in plasma and liver from untargeted metabolomics including DIO-MASH mice treated with semaglutide (n = 12) or vehicle (n = 12) or control mice (n = 6). Differences between groups are expressed as Fold change (FC) and P values. Statistically significant differential expression is denoted by a unique colour with blue indicating reduced expression and red an increased expression.

Metabolites with decreased plasma levels in DIO-MASH mice were glycine (FC 0.75; P = 0.007), choline (FC 0.73; P = 0.03), betaine (FC 0.77; P = 0.003), sarcosine (FC 0.84; P = 0.04), cysteine (FC 0.65; P = 0.03), and hypotaurine. Unlike in the liver, three plasma metabolites showed increased levels: dimethylglycine (FC 1.70; P = 0.02), α-ketobyturate (FC 7.58; P = 0.002), α-hydroxybutyrate (FC 2.00; P = 0.003), and α-aminobyturate (FC 1.62; P = 0.03).

Similar to patients with MASLD versus healthy controls, DIO-MASH mice showed reduced expression of a large number of enzymes compared to chow (Fig. 4A. Supplementary Table S3, and Supplementary Figure S2). The enzymes with reduced expression were methionine adenosyltransferase 1A (log2FC −0.60; P = 0.0002), methionine adenosyltransferase 2B (log2FC −0.14; P = 0.003), glycine N-methyltransferase (log2FC −1.92; P < 0.0001), adenosylhomocysteinase (log2FC −1.23; P < 0.0001), serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 (log2FC −0.64; P < 0.0001), serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (log2FC −0.29; P < 0.0001), betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase (log2FC −0.61; P < 0.0001), pipecolic acid sarcosine oxidase (log2FC −1.08; P < 0.0001), sarcosine dehydrogenase (log2FC −1.18; P < 0.0001), aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family member (log2FC −0.61; P < 0.0001), cystathionine beta-synthase (log2FC −1.04; P < 0.0001), cystathionine gamma-lyase (log2FC −1.65; P < 0.0001), cysteine dioxygenase 1 (log2FC −0.87; P < 0.0001), cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase (log2FC −1.07; P < 0.0001), and glutamate-cysteine ligase M (log2FC −0.27; P = 0.002).

Volcano plot of enzymes in one-carbon metabolism (OCM) in RNAseq analyses of liver tissue from DIO-MASH mice vs chow (Panel A) and DIO-MASH mice treated with semaglutide vs vehicle (Panel B). Decreased expression is indicated in blue, increased expression in red, and grey indicates no difference. All analyses include correction for batch, sex, and multiple testing. Abbreviations are listed under Fig. 1.

Increased expression was found for the following six enzymes: Methionine adenosyltransferase 2A (log2FC 0.25; P = 0.02), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (log2FC 1.13; P > 0.0001), glutathione synthetase (log2FC 0.24; P = 0.03), glutathione peroxidase 2 (log2FC 2.49; P = 0.002), glutathione peroxidase 3 (log2FC 2.15; P > 0.0001), and glutathione peroxidase 4 (log2FC 0.72; P > 0.0001).

3.7DIO-MASH treated with semaglutide vs vehicleOverall, 12 weeks of semaglutide reversed, and in some cases normalized, many of the changes in metabolites and enzyme expression levels in the DIO-MASH mice compared to vehicle (Table 3, Fig. 4B). As shown in Table 3, only one metabolite showed decreased levels in the liver (taurine log2FC 0.71; P = 0.006). Metabolites with increased hepatic levels were found in the methionine cycle (methionine log2FC 1.55: P = 0.005, s-adenosyl methionine log2FC 1.39; P = 0.001, and homocysteine log2FC 3.88; P = 0.001), folate cycle (serine log2FC 1.66; P = 0.005, glycine log2FC 1.41 P = 0.002, and riboflavin log2FC 1.42; P = 0.002), choline oxidation pathway (betaine log2FC 1.79; P = 0.01), and transsulfuration pathway (cystathionine log2FC 1.70; P = 0.006, cysteine log2FC 1.20; P = 0.04, and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate log2FC 1.34; P = 0.04).

In plasma, only minor changes occurred with decreased levels expression of s-adenosyl homocysteine (log2FC 0.57; P = 0.02) and alfa-ketobutyrate (log 2FC 0.49; P = 0.002). Two metabolites showed increased expression (betaine log 2FC 1.38; P = 0.0001 and hypotaurine log 2FC 1.76; P = 0.0006).

The RNAseq analyses showed mainly showed increased expression of enzymes. The only enzymes with reduced expression were identified in the folate cycle (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase log2FC −0.53; P < 0.0001) and in glutathione production (glutathione synthetase log2FC −0.34; P < 0.0001, glutathione-disulfide reductase log2FC −0.13; P = 0.04, glutathione peroxidase 4 log2FC −0.50; P < 0.0001).

The enzymes with increased hepatic expression following semaglutide versus vehicle were found in several pathways, including the methionine cycle (methionine adenosyltransferase 1A log2FC 0.64; P < 0.0001, methionine adenosyltransferase 2B log2FC 0.12; P = 0.0009, glycine N-methyltransferase log2FC 0.88; P < 0.0001, and adenosylhomocysteinase log2FC 0.81; P < 0.0001), folate cycle (serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 log2FC 0.53; P < 0.0001), choline oxidation pathway (aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family member 1 log2FC 0.20; P = 0.008, betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase log2FC 0.26; P = 0.0007, dimethylglycine dehydrogenase log2FC 0.23; P = 0.01, pipecolic acid and sarcosine oxidase log2FC 0.73; P < 0.0001, and sarcosine dehydrogenase log2FC 0.44; P < 0.0001), the transsulfuration pathway (cystathionine beta synthase log2FC 0.37; P = 0.01, cystathionine gamma-lyase log2FC 0.38; P = 0.02), and cysteine oxidation (cysteine dioxygenase 1 log2FC 0.61; P < 0.0001).

4Discussion4.1OCM pathway disruptions in MASLDIn this study, we observed that MASLD was associated with alterations in OCM pathways reflecting metabolic stress with increased activity in the methionine and folate cycles, as well as an upregulated transsulfuration pathway. These alterations were evident in metabolite levels and hepatic gene expression, both in MASLD patients and in animal models, suggesting a systemic change in OCM dynamics. In addition, increased glutamate and GSG index levels in MASLD patients likely indicate increased oxidative stress [17,22]. Detailed analysis of MASLD-related metabolic changes indicated elevated levels of α-hydroxybutyrate and cystathionine in the transsulfuration pathway, coupled with decreased levels of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (active vitamin B6). Cystathionine, formed from serine and homocysteine, was elevated, while serine itself was reduced in MASLD. The observed reduction in serine might reflect increased demand due to increased flux through the folate cycle and transsulfuration pathway. Betaine, a key component of the methionine cycle, was also found to be reduced in MASLD, which may reflect its increased utilization to accommodate the increased metabolic activity within the methionine cycle. Folate levels were also decreased, possibly reflecting the increased formation of homocysteine in MASLD. These findings underscore the significant strain on OCM-related pathways in MASLD, which may contribute to metabolic and cellular stress.

4.2Differential impact of MASLD severity on OCM pathwaysIn our study, few changes were observed when comparing patients with MASH vs. MASL, but pronounced changes were seen in patients with significant fibrosis compared to no/mild fibrosis. Patients with significant fibrosis exhibited pronounced changes in OCM pathways, particularly in transsulfuration and glutathione metabolism. Significant fibrosis was linked with increased metabolites such as choline, cystathionine, α-hydroxybutyrate, and glutamate, along with a markedly increased GSG index, indicating elevated oxidative stress and metabolic disturbance. These patterns suggest that OCM pathway disruption worsens with disease progression and that OCM metabolites might serve as indicators of disease severity.

4.3Semaglutide reverses OCM changes in animal modelsAs previously reported [26,27] and confirmed in this study, the DIO-MASH mouse model demonstrated excellent clinical translatability to MASLD in humans. The DIO-MASH mouse model replicated many MASLD-associated OCM alterations observed in humans, including changes in the methionine and transsulfuration pathways. Twelve weeks of treatment with semaglutide led to reduced fibrosis and normalization of metabolic markers, including weight. Semaglutide was also associated with reversal or mitigation of many observed disruptions in OCM.

MASLD was associated with lower levels of serine and glycine, which coupled with increased cystathionine and α-hydroxybutyrate, could indicate a shift in amino acid metabolism and a disruption of the feedback loop of the liver-alpha cell axis [30,31]. Elevated glutamate levels along with the increased GSG index also point to disrupted amino acid metabolism and the changes could eventually affect the hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. MASLD was associated with downregulated enzymes in key pathways, which, combined with upregulated glutathione metabolism, suggests a compensatory response to oxidative stress. Reversing these changes may underlie the beneficial effects of semaglutide observed in DIO-MASH mice. The findings also suggest that monitoring of treatment response could include OCM metabolites such as the GSG index and plasma betaine, especially as it returned to normal levels with semaglutide treatment. Weight loss remains a cornerstone in the management of MASLD and is likely a major driver of the effects observed with semaglutide in our animal model. Our study design did not allow for a clear distinction between weight loss-dependent and -independent mechanisms, such as epigenetic modifications. Future studies could consider an assessment of epigenetic changes in animal studies using, e.g., pair-feeding or weight-matched control groups. Autophagy, oxidative stress, and the role of glutathione in MASLD

The increased flux through transsulfuration and glutathione synthesis pathways in MASLD patients may reflect a response to elevated oxidative stress. Glutathione, a key antioxidant, plays a crucial role in maintaining liver health, and reduced levels have been associated with oxidative stress, hepatic steatosis, and inflammation, which is supported by elevated turnover of glycine, serine, and glutamate [32]. Increased p62, linked to autophagy in MASLD, suggests a role in clearing damaged mitochondria and protein aggregates, connecting autophagy, oxidative stress, and disease severity [33]. In contrast to previous evidence [34], we found no differences in homocysteine levels. We did, however, identify disruptions in the folate cycle and choline oxidation, involved in maintaining S-adenosylmethionine via homocysteine re-methylation. Such alterations have been linked to epigenetic changes and insulin resistance [35]. Maintaining adequate levels of methyl donors could be critical for preserving liver cell homeostasis and preventing further metabolic imbalance. Our findings align with evidence suggesting that changes in methyl donors, including folate, could influence gene expression and liver health in MASLD [36,37].

4.4Limitations and need for focused future researchThe interpretation of our findings is challenging due to the complexity of OCM pathways and the possible influence of confounding factors, such as obesity, weight reduction, and dietary intake, which were unavailable for patients with MASLD. Taken together, this makes it difficult to make definite conclusions regarding the relationship between OCM metabolites and gene expression changes in MASLD. Distinguishing between the direct effects of semaglutide and those mediated by weight loss is challenging as beneficial outcomes, such as improved glycemic control, are closely linked with weight reduction. We did not include animals with matched for weight loss to the semaglutide-treated group and are unable to evaluate if observed alterations in OCM reflect direct actions of semaglutide or are secondary to losing weight. Future studies should attempt to distinguish the impacts of semaglutide-induced weight loss from direct effects of semaglutide on hepatic metabolism. Additionally, the role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in MASLD progression warrants further exploration, particularly in the context of autophagy markers such as p62, which correlates with oxidative stress [33,38].

5ConclusionsBy combining analyses of liver tissue and plasma from patients with MASLD and advanced fibrosis with animal studies, this study found marked alterations in OCM metabolism that reversed following treatment with semaglutide. Our study sheds light on the changes in OCM that occur in MASLD, likely driven by oxidative and metabolic stress. Semaglutide showed promise in reversing these changes in animal models, by improving metabolic health and reducing oxidative stress. These findings deepen our understanding of MASLD pathophysiology and may aid in identifying new biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring treatment response, although further studies are needed to validate these observations in clinical practice.

Data statementSummary data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

FundingThe study is supported by Novo Nordisk, Maaloev, Nicolai J. Wewer Albrechtsen is supported by NNF Excellence Emerging Investigator Grant – Endocrinology and Metabolism (Application No. NNF19OC0055001), EFSD Future Leader Award (NNF21SA0072746) and DFF Sapere Aude (1052–00003B).

Lise Lotte Gluud has received consulting fees and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations or manuscript writing from: Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Norgine, Sobi, Becton Dickinson, and Alexion.

Jenny Norlin, Sanne Veidal, Dorte Holst, Anne Bugge, Lea Mørch Harder, Gianluca Mazzoni, Birgitte Martine Viuff, Henning Hvid, Kristian Moss Bendtsen and Elisabeth Douglas Galsgaard are employed at Novo Nordisk A/S.