Sepsis is a serious medical condition with a high mortality rate where patients experience a severe infection. In a normal operation, the immune and physiological systems work together to eliminate dangerous infections. On the other hand, sepsis occurs when the body cannot control these normal physiological reactions. In an ideal situation, the first interaction between the immune system and a pathogen would result in the total elimination of the infection and a quick return to balance in the host's body. Increased macrophage and neutrophil activity can accelerate the septic response. Sepsis happens because of many things, such as more cell and tissue damage, faster lymphocyte cell death, longer neutrophil cell death, and too many lymphocytes costimulatory molecules being made. Various interactions between the coagulation system and the inflammatory response result in an imbalanced reaction from both systems. Identifying patients who could potentially benefit from immunomodulatory therapy and assisting in diagnosing sepsis are important applications of biomarkers.

La sepsis es una enfermedad grave con una alta tasa de mortalidad, en la que los pacientes experimentan una infección grave. En condiciones normales, los sistemas inmunitario y fisiológico trabajan en conjunto para eliminar infecciones peligrosas. Por otro lado, la sepsis ocurre cuando el organismo no puede controlar estas reacciones fisiológicas normales. Idealmente, la primera interacción entre el sistema inmunitario y un patógeno resultaría en la eliminación total de la infección y un rápido restablecimiento del equilibrio en el organismo del huésped. El aumento de la actividad de macrófagos y neutrófilos puede acelerar la respuesta séptica. La sepsis se produce debido a diversos factores, como un mayor daño celular y tisular, una muerte celular más rápida de los linfocitos, una muerte celular más prolongada de los neutrófilos y una producción excesiva de moléculas coestimulantes de linfocitos. Diversas interacciones entre el sistema de coagulación y la respuesta inflamatoria resultan en una reacción desequilibrada de ambos sistemas. Identificar a los pacientes que podrían beneficiarse de la terapia inmunomoduladora, y ayudar en el diagnóstico de la sepsis son aplicaciones importantes de los biomarcadores.

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. When two or more criteria including temperature (>38°C or <36°C), heart rate (>90 beats per minute), respiratory rate (>20 or PaCO2 <32mm Hg) and white blood cell count (>12K or <4Kmm−3, or >10% bands) are present, clinicians classify the condition as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). SIRS can be diagnosed as sepsis when an infection is identified as the root cause.1 It is not always necessary to have a positive pathogen culture to diagnose sepsis. A culture may not be required in cases with a strong indication of infection, such as the presence of neutrophils in a normally sterile area like the peritoneum.2 A serious condition, severe sepsis, occurs when the septic process reaches a level of severity where the functioning of one or more organs is disrupted. Severe sepsis can cause low blood pressure, which is one indication of septic shock.3 Septic shock is a subset of sepsis in which underlying circulatory and cellular/metabolic abnormalities are profound enough to substantially increase mortality. It is clinically identified by the requirement of vasopressor therapy to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65mm Hg and serum lactate level >2mmol/L despite adequate fluid resuscitation. Ranked by severity: Sepsis is a more serious condition compared to septic shock, which is essentially a form of sepsis.4 A comprehensive analysis of individuals with severe sepsis from an international database provided valuable insights into the development of the condition, according to a 2009 assessment.5 Based on data collected from over 11,000 patients across 37 countries, the study has identified several key symptoms of sepsis.6 A significant number of patients (57%) presented with gram-negative infections, while 44% had gram-positive infections. Additionally, fungal infections were observed in many patients, affecting approximately 11% of the individuals.7–10 It is important to note that there were certain cases where the total percentage of illnesses exceeded 100%. In 47% of cases, the lungs had the highest infection rate among the patients. The abdomen was affected in 23% of cases, while the urinary tract was affected in 8% of cases.11 A notable portion of patients, including the individual in this case study, also experienced diabetes (24%), chronic lung disease or malignancy (16%), congestive heart failure (14%), and renal insufficiency (11%).12 The database revealed a significant number of fatalities, highlighting the severity of sepsis as a life-threatening condition. There was no noticeable decrease in sepsis mortality throughout the patient enrollment period. Having a thorough understanding of sepsis pathology is crucial for enhancing survival rates.

Sepsis and phagocytic cellsWhen a bacterial pathogen enters a sterile environment, the local cells that detect the infiltrator usually trigger an inflammatory response. In cases with only a few invading germs, the body's local immune responses can often eliminate the infections successfully.13 Macrophages play a crucial role in engulfing bacteria and releasing proinflammatory cytokines, which activate the innate immune system to fight against the bacterial pathogen.14 This probably occurred to patient during the initial stages of the infection, after the rupture of her colonic diverticulum. M1 cells are macrophages that produce chemokines like IL-8 (CXCL8) and cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF, and IL-615 (additional information regarding biomarkers will be provided below). Dendritic cells and macrophages are specialized cells that play a crucial role in the immune response by alerting the body to the presence of an infection.16 They achieve this by identifying pathogen-associated molecular patterns and common microbial molecules in a diverse range of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Activated peripheral blood cells contain receptors that can detect various substances.17–21 As a result, cytokines are generated, contributing to the natural inflammatory response. One of the most widely recognized PRRs are toll-like receptors, which can detect various components of bacterial and fungal cell walls and viral and bacterial nucleic acids.22 During the innate response to bacterial contact, macrophages experience an increase in the levels of CD80 and CD86, which are costimulatory molecules. The molecules are crucial in the interactions between innate and adaptive immune responses (see the following section).23 The initial discharge of pathogens from the perforated diverticulum was prevented by local peritoneal macrophages when bacteria invaded a sterile zone. The patient's condition is being closely monitored to ensure minimal complications, primarily focusing on providing effective local treatment.24 It is expected that the newly recruited neutrophils, if they overcome this initial defense barrier, will be able to eliminate the pathogens effectively.25

Inflammatory cellsIn most cases, when inflammation occurs, more cells are needed to help clear the pathogens. Endothelial cell surface adhesion molecules are produced due to cytokine secretion from nearby inflammatory cells.26 The transportation of white blood cells to the site of inflammation occurs when they temporarily attach to the lining cells of the blood vessels and pass through the vessel wall. MicroRNAs have also been linked to the modulation of microbial adhesion molecules.27 Peripheral blood contains a variety of cell categories, such as monocytes, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. Neutrophils make up more than half of the blood cells in individuals who are in good health.28 Neutrophils, also known as polymorphonuclear leukocytes, have a variety of nuclear structures. Phagocytic cells are commonly referred to as macrophages and neutrophils.29 Neutrophils and macrophages have different ways of eliminating pathogens. The body utilizes energy for various functions, some of which are necessary while others are not. Phosphocytosis is an important intracellular mechanism crucial in eradicating pathogens by phagocytic cells. It serves as the initial stage in the eradication process.30 Upon entering the body, bacteria are often surrounded by host proteins, such as complement fragments and antibodies. Neutrophil surface receptors facilitate phosphocytosis by recognizing opsonized proteins on bacterial surfaces. PRRs include complement receptors and the Fc subunit of immunoglobulins.31 The elimination of the bacterium is a direct outcome of the various processes taking place within the neutrophils. Vacuoles called pneugosomes contain microorganisms that have been ingested through phagocytosis. It forms phagosomes by interacting with specific intracellular granules.32 Neutrophils possess granules with antimicrobial properties. The earliest (azurophilic) granules contain α-defensins, antimicrobial proteases such as cathepsin G and elastase, myeloperoxidase, and a protein that enhances bacterial permeability. In addition, secondary granules contain antimicrobial peptides like lactoferrin, metalloproteases, and lysozyme.33 The interaction between bacteria and neutrophil granules creates an unfavorable local environment. This environment has a lower pH and contains powerful proteases designed to eliminate pathogens. In addition, there are implications of mortality related to the dependence on oxygen and other mechanisms. Reactive oxygen intermediates produced by neutrophils, such as superoxide anion and hydroxyl radicals, can trigger a respiratory surge.34 A desirable scenario entails the effective collaboration of mediators, ensuring they stay within the phagolysosome. This allows for the swift eradication of bacteria while maintaining the host's well-being. In certain situations, sepsis can occur when microbes can evade the body's defenses or when the body is harmed by its response.35 Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are formed in response to bacterial interactions. The neutrophil extracellular matrix (NET) comprises fragments of neutrophil DNA, antimicrobial peptides, and histones. This response helps in the fight against pathogens. Nets are made up of substances that help prevent the growth of microorganisms.35

Sepsis occurs when the body's inflammatory response to an infection becomes severe enough to disrupt important physiological functions. The given description may not be entirely accurate, but this response can be classified as an overly enthusiastic or exaggerated inflammatory reaction.36 In cases with a significant bacterial load, especially with highly virulent bacteria, it can trigger an inflammatory reaction corresponding to the level of bacterial stimulation. Nevertheless, for individuals with a susceptibility to sepsis, the resulting unintended consequences pose significant challenges in terms of effective management.37 A careful examination of the medical case study reveals that an intervention aimed at reducing inflammation could have positive and negative effects in this scenario. This has the potential to reduce the harmful effects of inflammation. However, it can weaken the body's ability to fight off infections. It is widely acknowledged that individuals with weakened immune systems are at a higher risk of developing infections, including sepsis.38

LymphocytesDuring bacterial infections, lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) have a strong and essential interaction. APCs play a crucial role in the development of an adaptive immune response.39 Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) work with costimulatory factors and CD3 proteins on the cell surface to present microbial antigens to T lymphocytes. After receiving the appropriate signals, effector CD4+ T cells release cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ. These cytokines activate phagocytic cells to eliminate pathogens within the cell.40 Moreover, effector CD4+ T cells play a crucial role in stimulating the production of antibodies, which offer defense against microbial infection by interacting with B cells. Furthermore, T cells enhance the production of CD40 ligand, which combines with APC CD40 to form a complex. This method enhances the communication between innate and adaptive systems by maintaining the expression of costimulatory molecules and increasing the secretion of IL-12.41 Patients suffering from sepsis often experience a significant decrease in lymphocyte counts as a result of apoptosis. The decrease in question is expected to significantly impact the development of an immunosuppressive state, a common occurrence in the final stages of sepsis. Patients with compromised health are more susceptible to acquiring additional infections.42 Immunohistochemistry staining revealed a decrease in the number of splenic B cells and CD4+ T cells in the postmortem spleens of patients with sepsis. Patients with sepsis often experience decreased CD4+ T cells in their peripheral blood. Unlike individuals who are in a state of excellent health. It is worth mentioning that individuals who show improvement in sepsis also experience a decrease in T cell apoptosis.43 Using a two-hit paradigm, an evaluation was conducted on T cells in the spleens of mice. In this specific case, a mixed microbial infection occurred due to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). After five days, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was introduced intravenously as part of an experiment. Based on the findings, it is evident that the mice produced a lower amount of IFN-γ.44 Nevertheless, in a controlled laboratory environment, the splenic T cells demonstrate similar levels of IFN-γ production when stimulated with IL-12, as observed in the control group. The findings suggest that the ability of T cells to respond to subsequent infections may be compromised due to a potential lack of effective stimulation by APCs following an initial infection.45 A possible explanation for decreased T cell functionality in sepsis is modifying antigen-presenting cell (APC) signaling pathways through costimulatory molecules. This can result in the development of anergic cells and ultimately cell death. It has been noted that patients diagnosed with sepsis tend to have a higher prevalence of the inhibitory costimulatory ligand CTLA-4/CD152 on their T cells.46 Alongside this rise, there is a decrease in the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD86 on monocytes. Based on research conducted on individuals who have recovered from sepsis, it has been observed that the decline in T cell apoptosis becomes less pronounced over time. This decline was associated with an increase in CD86 overexpression and a decrease in CTLA-4 expression.47 One possible reason for the reduced lymphocyte activity in septic patients is the excessive presence of regulatory T cells (Tregs), specifically CD4+CD25+ cells. Whole-blood samples collected from septic patients showed a reduced ability of T cells to respond to antigens, as observed in studies conducted outside of the body. When examining splenocytes from septic rodents, it was observed that the proliferation response was restored when Foxp3, a crucial transcription factor for regulatory T cells (Tregs), was absent.48

Immune responsible moleculesOne well-known and well-researched aspect of developing sepsis is the increased generation of proinflammatory cytokines during the innate immune response (see the following biomarker section).49 Recent studies have demonstrated that the host response to sepsis is significantly influenced by the interplay between antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and the adaptive immune system. Some interactions happened because of the septic patient's weakened immune system. The interaction between the two branches of the immune system is expanding, particularly how the first reaction affects the second response and possible consequences for the prognosis of sepsis patients in the long run. Significant lymphocyte apoptosis is frequently observed in sepsis patients, which reduces the capacity of septic mouse monocytes to activate T cells.50 The immunological synapse that links APC and T cells depends on cell surface proteins called CSMs. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) must express these substances to regulate T cell activation properly. The fate of T cell growth is largely determined by the secondary signals, which can either stimulate or inhibit it. This can ultimately lead to anaerobic responses and cell death.51 A thorough analysis of the B7 family's cell surface molecules, CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2) has been conducted. As ligands for CD28/CTLA-4 receptors on T cells, CSMs are found in APCs and proliferate in response to various microbiological stimuli. Like other signaling systems, CD80 and CD86 can interact with CD28 or CTLA-4 to produce stimulatory or inhibitory responses. T cells become more active and proliferative during transit when CD28 is activated.52 Conversely, CTLA-4 is only generated after T cell activation and functions to impede the T cell's reaction to the antigen. A monoclonal agonist antibody for CD28 was used in a clinical experiment that revealed the possible significance of the B7:CD28 pathway in the innate response. The study subjects treated with antibodies exhibited sepsis-like clinical symptoms and a strong inflammatory response.53 Research findings demonstrate that CLP can lead to increased CD80 expression in various types of monocytes found in rodents’ peritoneal, splenic, and peripheral blood. This phenomenon mimics the development of sepsis in humans and the occurrence of bowel perforation. In contrast, the expression of CD86 is reduced in the peritoneum, but increased in the spleen and peripheral circulation.54 Although there is significant sequence and ligand overlap, the change in expression indicates that the roles of CD80 and CD86 expression may differ depending on the location of the antigen-presenting cells about the infection site. A comparable form of compartmentalization has been observed in the cytokine response to infection.55 In addition, it may substantially impact the probability of a severe localized infection advancing to systemic immunosuppression, a condition frequently observed in the later stages of sepsis.56 There are noticeable differences in CD80 and CD86 expression levels in sepsis cases, which can impact survival. Comparing the survival rates of CD86−/− mice and wild-type controls to CD80−/− mice or mice treated with anti-CD80 monoclonal antibody before CLP reveals a significant improvement. Severe patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) show increased CD80 expression on their circulating monocytes.57 Elevated levels of CD80, associated with shock, indicate the negative impact of the protein. However, there is no observed connection with survival. The expression of CD86 in these cells is lower compared to the healthy control group. On the other hand, individuals who have survived septic patients show higher levels of expression than those who did not survive.58

A medical case study highlights the connection between CD40 and its T cell ligand, CD154 or CD40L, shedding light on the immune response to infection. For macrophages to efficiently engulf bacteria, CD40 must be expressed. The patient needs to undergo this procedure to develop a response to the infection. T cells that are activated show higher levels of CD40L expression.59 Due to the binding of CD80 and CD86 to CD40 on APCs, their expression levels are elevated. In addition, it enhances the secretion of IL-12, an important regulator of T cell differentiation and activation. Mortality rates in CD40−/− mice are lower than wild-type controls, even though septic mice have higher levels of CD40. In addition, the rodents’ blood lacking CD40−/− showed a significant decrease in IL-6 levels.60 Patients with sepsis showed increased levels of CD40 expression on mononuclear cells in their peripheral blood. There is a correlation between shock and higher levels of CD40 expression.29 On the other hand, higher survival rates are linked to higher expression levels. Clearly, when mice were given an agonistic anti-CD40 antibody, it was observed that lymphocyte apoptosis decreased and overall survival improved after CLP.61

In addition, PD-L1 and PD-L2 are important members of the B7 family. Through the PD-1 T cell receptor, these individuals experience decreased energy and ultimately succumb. PD-L1 is widely expressed on various cells, including APCs, B cells, splenic T cells, and other nonhematopoietic cells. Some specific immune cells, such as peritoneal B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and bone marrow-derived mast cells, can be activated to express PD-L2.31,32 T cells infected with the virus exhibit increased levels of PD-1.62 It has been observed that animals lacking the PD-1 signaling pathway show increased resistance to Listeria monocytogenes infection. This indicates that the signaling system may affect the host's immune response to pathogens.62 Although PD-1 has been studied in animal models involving bacterial infections and sepsis, there is limited research specifically focused on sepsis patients and their relationship with PD-L1 and PD-L2. When CLP is present, rodents that lack PD-1 show lower mortality rates and decreased production of inflammatory cytokines and bacterial burden in the body and abdomen.63 The findings of this study come as a surprise to some extent, as the lack of a T cell-inhibitory pathway could have indicated a stronger inflammatory reaction. This is because activated T cells release IL-2, which triggers the activation of cytotoxic T cells. Despite the lack of extensive evidence, it is undeniable that CSMs play a crucial role in the body's immune response to pathogens. They greatly disturb the delicate balance between clearing infections and the excessive inflammatory response seen in sepsis.64

Effects of sepsis on cell proliferationIn sepsis cases, mortality remains high, with approximately 40% of patients not surviving beyond 28 days, particularly when complications arise during anesthesia and critical care management. The pathophysiology of sepsis places great importance on the occurrence of individual cell death.65 Two mechanisms contribute to the death of cells: apoptosis and necrosis. This section describes the responses of specific cell types to necrotic and apoptotic pathways. The patient's condition probably worsened due to the dysregulation of apoptosis and necrosis in inflammatory cells.66

Cell apoptosisApoptosis, or “programmed cell death,” is a complex process involving multiple synchronized stages. The plasma membrane's division occurs during the later stages of apoptosis. Rare instances occur where harmful substances are released from cells into the surrounding environment, as long as the plasma membranes remain undamaged.67 Apoptotic cells display various changes in their appearance, such as the development of plasma membrane blebs, nuclear fragmentation, and chromatin condensation. Various techniques can be used to detect apoptotic cells, such as staining for terminal deoxynucleotidal transferase, chromatin laddering, or activation of caspases.68 Apoptosis plays a crucial role in maintaining proper development by regulating proliferation. Apoptotic mechanisms play a crucial role in removing unnecessary cells during the development of organs. Scientific research has found that over time, a significant amount of bone marrow and lymph nodes can accumulate in the body if cells are not eliminated through apoptosis.69 In addition, apoptosis could potentially contribute to the elimination of cancer cells. As a result, any disruptions in this process might be linked to the formation of certain types of cancer.70

Two fundamental pathways initiate apoptosis: extrinsic and intrinsic.71 Cell death occurs through the extrinsic pathway when external proteins attach to receptors on the cell surface. The process in question is called the death receptor pathway.72 Several molecules are involved in this particular case, including FAS, TRAIL, and TNF. Upon receptor binding, the FAS-associated death domain of the adaptor protein relocates to the inner surface of the cell membrane.73 As a result, a cascade of internal mechanisms is set in motion, leading to the synthesis of more proteins that prevent cell death through a negative feedback loop. According to research, caspase-3 is commonly called the “master executioner” due to its effective performance.74

When it comes to the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, the mitochondria play a significant role. This method heavily depends on the presence of γ radiation, oxygen radicals, or DNA damage. In a fragile balance, various proapoptotic proteins, such as Bim, Bax, and PUMA, exist alongside antiapoptotic proteins, like BCL-2, BCL-XL, and others.75 Factors that influence specific proteins are linked to the onset of the apoptotic signal. For example, PUMA regulates apoptosis, a cellular response to DNA damage. When proapoptotic proteins are present, mitochondria release cytochrome c, triggering a series of events that activate caspase-9. Following the completion of the extrinsic pathway, caspase-3 is activated.76

Cell necrosisThe second primary cause of cellular demise is necrosis. Ischemia-induced cellular ATP depletion has historically been associated with ischemia-induced necrosis. The compromised membranes of necrotic cells permit detrimental proteolytic enzymes to pass through. These enzymes are released by intracellular organelles like lysosomes into the cytoplasm or, if a plasma membrane rupture occurs, into the adjacent tissue.77 Phosphocytic cells are responsible for eliminating pathogens during the initial phases of an infection, as previously stated in the corresponding section. Tests on adoptive transfer subjects have demonstrated that apoptosis is more significant than necrosis in sepsis. Injecting necrotic cells decreased mortality rates in sick rodents, whereas administering apoptotic cells increased mortality.78

Apoptosis roleExisting evidence suggests that apoptosis-associated cell death holds significant therapeutic significance in this particular situation, as necrosis has been observed in animal models of sepsis and endotoxemia and septic patients.79 Apoptosis has been observed in various cell types, such as endothelial, muscle, and neuronal cells. However, sepsis causes the most severe apoptosis in lymphocytes and gastrointestinal epithelial cells.80 The Hotchkiss group conducted complex and time-sensitive investigations on patients who had succumbed to sepsis, and they were the first to document this important discovery in human subjects. Increased cell death has been noted in lymphoid organs like the thymus and spleen and in lymphoid sections of other organs such as the large intestine. The occurrence of this condition in tissues outside of lymph nodes is relatively low.81 Furthermore, there was no conclusive evidence linking the organ injury observed in these patients to the low occurrence of apoptosis in kidney and lung epithelial cells and other organs such as the liver. Further research by the same group revealed that in the spleens of septic patients, macrophages and other T cell subsets showed very low susceptibility to apoptosis.82 Nevertheless, dendritic cells (including follicular and interdigitating cells), B cells, and CD4+ T lymphocyte subsets showed increased susceptibility. A similar pattern of cell death was later observed in newborn and young patients who died from sepsis.82 Septic patients often experience prolonged lymphopenia due to increased lymphocyte apoptosis, affecting various subpopulations of lymphocytes in circulation.83 Like splenic lymphocytes, most circulating CD4+ T and B cells go through apoptosis. However, there have been findings of reduced levels of CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells.84 It is important to note that the severity of symptoms and prognosis strongly correlated with the level of apoptosis in both studies.85

Much data obtained from animal studies supports the previously mentioned results. Similar levels of lymphocyte apoptosis have been observed in the intestinal epithelium and lymphoid organs of the murine CLP model of polymicrobial sepsis, mirroring the findings in humans with sepsis.86 Apoptosis can occur in various nonlymphoid sites and cell subsets, including kidney tubule cells, skeletal muscle cells, and lung alveolar, respiratory, and capillary endothelial cells, during CLP sepsis.86 Interestingly, despite the decrease in lymphocyte levels caused by CLP during the initial stage of sepsis, several studies have found higher peripheral lymphocyte counts in mice that did not survive than those that did. However, these counts did not specify the exact ratio of cells undergoing apoptosis to those not undergoing.87

The rate of lymphocyte apoptosis can harm neutrophils. Powerful antibacterial neutrophils are initially recruited to the infection site, where they play a vital role in containing the infectious attack. Furthermore, neutrophils can undergo apoptosis, ensuring strict control over the inflammation they generate. Extensive documentation exists on the prolonged suppression of neutrophil apoptosis in patients with sepsis.88 It appears that extended neutrophil apoptosis may have a role in causing harm to organs and leading to death. Continuous neutrophil activation can cause significant damage to nearby cells and tissues by constantly producing harmful metabolites.89

There are still many unanswered questions regarding apoptosis in septic patients. The range of cells or tissues that can induce apoptosis is likely much larger than currently understood. Examining the origin or qualities of septic damage may reveal new patterns in apoptotic depletion. For instance, Listeria monocytogenes triggers a rapid apoptosis in hepatocytes, whereas Staphylococcus pyogenes does not induce the same apoptosis in macrophages and neutrophils.90 Further research in this area can be greatly improved by using a recently developed mouse model that includes hCD34+ hematopoietic cord blood stem cells. This model accurately represents the full functionality of the human innate and adaptive immune systems.91

In lymphocytes, accelerated apoptosis may significantly impact the development of sepsis. An advanced adoptive transfer experiment was conducted using septic rodents to examine the concept mentioned earlier.92 In addition, a significant decrease in immune function occurs during the later stages of sepsis. The primary cause of this illness is most likely the loss of lymphocytes due to apoptosis. The immunosuppressive mechanism is believed to encompass two key processes: the direct elimination of crucial effector cells or the induction of immune tolerance through apoptosis in macrophages and dendritic cells that survive.93 Several antiapoptotic medications have been suggested as potential approaches to hinder or reverse these processes, as the long-term weakening of the immune system's defenses undoubtedly puts the individual at a disadvantage and increases susceptibility to future infections. Various therapeutic approaches have been extensively studied, including the inhibition of CD95, the overexpression of BCL-2, the inhibition of caspases (such as caspase-3 and caspase-8), and the use of no caspase protease inhibitors.94 Unfortunately, trials for these experimental treatments have not yet started. The complexity of the signaling networks that regulate apoptosis may contribute to the unsuitability of these targets for therapeutic purposes.95

Sepsis and blood coagulationThe association between sepsis-induced coagulation dysfunction and an atypical accumulation of fibrin in blood vessels is widely acknowledged. Beyond that, it remains exceedingly challenging to reach an agreement.96 There is intense debate regarding the function of coagulopathy in sepsis, with divergent opinions regarding whether it is a causal factor or merely an observer. The inconsistent results of anticoagulant medications in clinical studies for sepsis add layer of complexity to the subject, especially when compared to their effect on 28-day all-cause mortality.97 A week after contracting a bacterial infection, our patient developed severe sepsis and hypotension as a result of disseminated intravascular coagulation. When the body's typical coagulation process is disrupted, virtually impermeable blood clots may develop. These clots have the potential to obstruct the organ's minute blood vessels.98 Those with protracted clotting times, low platelet counts, and low fibrinogen levels may experience a depletion of platelets and coagulation components that surpasses their restoration rate. Patients diagnosed with DIC pose a peculiar dilemma due to their propensity for thrombosis and increased risk of hemorrhaging in comparison to fit individuals. Skin petechiae are prominent indications of micro bleeding in various anatomical sites and are frequently observed in patients with DIC-induced consumption coagulopathy.99

The resolution to this issue ought to be uncomplicated. The microvasculature was physically obstructed in this instance by the aggregates. Damage caused by ischemia and reperfusion can result in severe complications, such as failure of multiple organs and mortality.100 To safeguard organ function, it is necessary to halt or prevent the formation of blood clots. Nevertheless, when confronted with practical situations, it is imperative to consider many intricate elements.101 Potential variables to considerable include shifts in the population's demographic composition, the coexistence of supplementary medical conditions, and the justifications for the inappropriateness of certain frequently prescribed medications, such as heparin. The impact of heparin therapy on the effectiveness of an investigational medication is being investigated in two clinical trials involving patients with sepsis.102

Anticoagulation and sepsisDespite the difficulties, efforts are being made to prevent unnecessary blood clot formation in patients with sepsis. Various points in the coagulation cascade are frequently targeted for pharmaceutical intervention.103 Various pharmaceutical or natural methods can be employed to achieve this goal. Certain molecules play a crucial role in the successful synthesis of fibrin. These molecules, such as tissue factor, cofactors Factor Va and VIIIa, and Factor Xa, act as checkpoints in the process. The extrinsic pathway is activated by tissue factor and is sped up by factors VIIIa and Va. Factor Xa is the coagulation enzyme required for both the extrinsic and intrinsic routes.104

While studying sepsis and its effects on patients, it has been observed that using anticoagulants can lead to different outcomes. However, by conducting correlation tests, it is possible to distinguish between trauma-induced coagulopathy and infection in patients. These tests can also help predict the prognosis of the patients.105 The clinic routinely conducts two clotting tests. The measurement of molecules in the tissue factor pathway is done using the prothrombin time (PT). Tissue factor (thromboplastin) from an external source is introduced into the patient's plasma to compensate for any inconsistencies in the laboratory reagents.106 The coagulation time is calculated as a ratio, known as the international normalized ratio, to a standard reagent value. It is common practice to use physical therapists to monitor individuals who are taking oral anticoagulants such as warfarin. The contact activation pathway that leads to the activation of Factor Xa can be assessed through the activated partial thromboplastin time, commonly known as APTT.107 Clotting time is evaluated by administering an exogenous phospholipid in the patient's plasma. APTT tests are commonly utilized to evaluate patients receiving intravenous anticoagulants, like heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin. Various assays can be utilized to measure clot disintegration, clot formation regulation, and clot creation. Only a few tests have practical value in treatment, even though numerous tests are used in research. As an example, markers such as D-dimer and fibrin degradation products (FDPs) can provide valuable insights into fibrinolysis and help assess the extent of coagulopathy.108

Thrombin is the final serine protease generated by the cascade. The primary role of this protein in the coagulation process is to break down fibrinogen into two smaller peptides known as fibrinopeptides A and B, resulting in the formation of oligomerized fibrin monomers. As mentioned, thrombin has various effects including fibriolysis, inflammation, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis. While there is potential for thrombin inhibitory drugs in sepsis, it is important to consider their significant role in inflammation through protease-activated receptors (PARs).109 Therefore, it may be premature and unproductive to utilize these drugs during severe coagulopathy of sepsis. A study examined the effectiveness of hirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor derived from the medical leech Hirudo medicinalis, in patients experiencing acute thrombotic events. The study involved Phase II and III clinical trials. However, the trials found that hirudin had a significant bleeding rate, no clear advantage over low-molecular-weight heparin or conventional heparin, and no noticeable impact on mortality outcomes.110 Researchers discovered that hirudin has been shown to decrease fibrin deposition in animal models of mixed microbial sepsis. However, it does not appear to impact organ perfusion significantly.111 In the KyberSept trial, a significant international Phase III clinical trial aimed at assessing antithrombin therapy for patients with severe sepsis, it was found that despite the natural ability of antithrombin to slow thrombin, the use of antithrombin medication did not improve survival rates. It is worth noting that antithrombin therapy has shown potential benefits for patient subpopulations with a significant risk of mortality (30–60%), as indicated by a meta-analysis of the KyberSept data.112 This discovery shows potential for future clinical research using patient classification standards.

Tissue factorsTissue factor, also known as thromboplastin, CD142, and Factor III, is a versatile transmembrane cofactor and receptor. The body initiates the clotting process.113 Tissue factor is typically not readily available to blood components as it is absent in the bloodstream. However, it can also manifest mysteriously and become procoagulant through an unidentified process. The mechanism by which the tissue factor transitions between high and low activity levels is fascinating. This concept highlights the redox-induced disulfide bonding between two specific cysteine residues in tissue factor (Cys186 and Cys209).114 Nevertheless, the limited conclusive evidence regarding free thiols in tissue factor, combined with insights from crystal structure data, indicates the potential presence of other factors contributing to the identification of tissue factor activity.115 Recent research has uncovered a soluble tissue factor that has prothrombotic properties. Due to alternative splicing, the transmembrane domain is absent and exon 5 is not produced in this factor. During coagulation, tissue factor binds to Factor VII on cell surfaces, activating it. Consequently, an enzyme-cofactor complex is formed, leading to an increase in the production of Factor Xa. Endothelial cells and platelets produce tissue factor pathway inhibitors (TFPI), effectively suppressing this checkpoint.116 TFPI inhibits the tissue factor-Factor VIIa complex in the presence of Factor Xa, leading to a dysfunctional quaternary structure. Heparin can displace TFPI, which has a relatively loose connection with endothelial cells and binds to their glycocalyx layer. In animal models of bacterial sepsis and human endotoxemia challenge tests, TFPI has demonstrated potential as a treatment for reducing Nevertheless, the effectiveness of recombinant TFPI (rTFPI) in reducing the 28-day all-cause mortality rate among patients diagnosed with severe sepsis was found to be insignificant in a coagulopathy.117 Phase III randomized clinical trial involving a substantial number of participants (n=1754). Interestingly, individuals with a low international normalized ratio (<1.2) experienced a notable improvement in their chances of survival. The survival rate showed a notable difference between the placebo group (22.9%) and the rTFPI group (12.0%), with the latter exhibiting a lower survival rate. The survival effect remained consistent despite accounting for therapy, baseline APACHE score, and log10 IL-6 levels. There may be some concerns about this anticoagulant's effectiveness in treating sepsis patients. There is a higher likelihood of bleeding in the central nervous, gastrointestinal, and respiratory systems in the rTFPI arm. In addition, there is a concerning interaction with heparin for medical purposes.

Va and VIIIa factorsDuring the coagulation process, two cofactors, factors VIIIa and Va, enhance the production of fibrin. Given the critical function these molecules play as checkpoints, nature has ingeniously devised the protein C anticoagulant pathway to inhibit both cofactors effectively. Within cellular contexts, the transportation of the protein C precursor to a preassembled complex is facilitated by the endothelium protein C receptor. This complex comprises thrombin and thrombomodulin (CD141), which act as cofactors on the membrane. This promotes the cleavage of activated protein C's precursor, a serine proteinase that breaks down Factors Va and VIIIa through limited proteolysis. When these crucial elements are absent, the coagulation process experiences a significant slowdown, leading to a notable decrease in thrombin production. In addition, components of the protein C pathway play a beneficial role in safeguarding cells from the harmful effects of sepsis. An interesting example is the ability of activated protein C to degrade cytotoxic histones released by injured cells. An investigation in the late 1980s involving nonhuman primates showcased the efficacy of using activated protein C as a pretreatment to decrease mortality caused by high doses of the gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli Based on the PROWESS clinical study, the FDA approved recombinant human activated protein C (drotrecogin alfa, activated) in 2001 as an additional treatment for patients diagnosed with severe sepsis.118

The significant concern of bleeding associated with drotrecogin alfa in almost all trials dampened the initial excitement surrounding a hopeful clinical study that demonstrated a 6.1% decrease in mortality and improved long-term organ function in acutely septic patients.119 Furthermore, research has indicated a minimal risk of mortality associated with this treatment option. However, it is important to note that it is not effective for managing severe sepsis in adult patients. In addition, research has indicated that it does not provide positive outcomes for children.120 Drotrecogin alfa is currently only prescribed to patients who meet specific criteria, and it is not considered a commonly used treatment option. Meeting certain criteria, such as a high APACHE score, being in a terminal condition, or having multiple organ failures are some examples of the necessary conditions. It suggests that administering anticoagulants early to critically ill patients provides a certain level of protection. A 30-nation volunteer initiative known as Surviving Sepsis aimed to provide comprehensive and evidence-based therapeutic care to patients suffering from severe sepsis and shock. The promotional material stated that individuals who were administered drotrecogin alfa within the initial 24h of admission to the intensive care unit while in a state of shock had an increased likelihood of survival.121

Various studies, including the PROWESS experiment, have shown that patients with low levels of circulating protein C tend to experience severe illness and have a less favorable prognosis. A Phase II trial was conducted to assess the effectiveness of protein C concentrate in critically ill children with meningococcemia, and the results were quite promising. The survival time of 12.3h is similar to what has been observed in previous small-scale clinical investigations. This medication effectively increased the levels of activated protein C in the blood, partially restoring the coagulation balance without any adverse bleeding effects.122 The results of this investigation disproved the conventional wisdom that patients suffering from acute sepsis ought to get the active enzyme since they are incapable of activating the protein C precursor. The only available option for treating severe protein C deficiency in newborns, an uncommon autosomal recessive disorder, is CeprotinTMR, a recombinant human protein C. A recent study focused on four premature infants who were at high risk of mortality due to severe bacterial sepsis, shock, and other comorbidities. The newborns were administered antithrombin and protein C concentrate, not part of the standard critical care treatment. After 48-h treatment with protein C concentrate, the levels of circulating protein C returned to normal, the purpuric cutaneous lesions disappeared, and the newborn's multiple organ dysfunction score became stable. All four babies made a complete recovery without any complications related to bleeding, clotting, or disruption of blood flow. There is a high demand for clinical trials investigating the efficacy of human protein C concentrate in pediatric sepsis patients. This particular group of individuals has a higher likelihood of experiencing blood coagulation problems. Although recombinant activated protein C (drotrecogin alfa) was initially approved based on early trial data (PROWESS trial), subsequent larger studies failed to replicate the survival benefit. The PROWESS-SHOCK trial, a Phase III randomized controlled study, demonstrated no significant reduction in mortality, leading to the withdrawal of the drug from the market.123,124 Furthermore, the high risk of serious bleeding events raised safety concerns. These findings underscore the complexity of sepsis treatment and the limitations of targeting a single pathway in such a heterogeneous syndrome.

Factor XaAlthough leeches and hirudin have a significant historical background as anticoagulants, several contemporary alternatives have surfaced since the 1930s introduction of heparin. Despite the potential drawbacks, low-molecular-weight heparin (specific to Factor Xa; 1987) and vitamin K antagonists (warfarin and coumadin; early 1950s) remain widely used as anticoagulants. The mentioned side effects include the requirement for intravenous administration, medication-induced thrombocytopenia, and difficulties in determining the ideal dosage. As a result, the finding of new oral Factor Xa inhibitors is highly promising. Factor Xa plays a crucial role in coagulation, being involved in both phases. A crucial cascade element affects both the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways. By inhibiting this component, we can effectively prevent the formation of blood clots. Apixaban, a newly discovered Factor Xa inhibitor, has shown promising results in animal models and could help patients prevent complications after knee replacement surgery.125 The anti-Factor Xa activity of BAY 59-7934 (rivaroxaban). This specific chemical belongs to a class of oxazolidinone derivatives discovered through high-throughput screening. These compounds are competitive inhibitors of Factor Xa by targeting its active site. Their oral bioavailability remains high despite their short half-life. Rivaroxaban has been extensively studied in various settings, including pre-operative evaluation in healthy individuals, animal models of thrombosis, and patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.126 Little is known about the effectiveness of these new medications in treating blood clotting disorders during a severe infection. A recent study has highlighted the important role of Factor Xa in signaling, particularly in the activation of PARs (PAR-1 and PAR-2). It is important to mention that this communication occurs when the coagulation activity of Factor Xa is not present. The findings of this study suggest that altering this molecule could have important implications for various physiological processes commonly seen in severe sepsis, such as acute lung injury, wound healing, and tissue regeneration.127

Cellular biomarkersBiomarkers are chemical entities that correlate with physiological or pathological changes. Although these compounds may not be the main cause of the illness, they suggest a biological basis. The plasma concentration of troponin, used for diagnosing acute myocardial infarction in patients, is a remarkable example of a biomarker.128 Utilizing biomarkers can be instrumental in guiding treatment decisions and diagnosing various diseases. The discovery of biomarkers for accurate sepsis diagnosis and patient monitoring in critical illness is a topic of significant interest, given the complex nature of the septic response. In the past, sepsis management focused on evaluating physiological markers.129

Physiology of septic patientsCurrently, medical professionals in the intensive care unit (ICU) closely monitor various laboratory parameters such as platelet count and serum sodium levels. They also closely monitor physiological data like heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration rate. This is particularly important for septic patients, who comprise most ICU cases. Nevertheless, the standard metrics mentioned lack the required reliability to provide a definitive diagnosis of sepsis.130 Furthermore, it is important to mention that patients with sepsis may show either heightened or reduced inflammation levels, even if they have noticeable physiological scores. The scoring systems commonly used in medical case studies, such as APACHE, SOFA, and PIRO, cannot fully capture patients’ complex immunoinflammatory status. As a result, several Phase III clinical trials have shown that the widespread use of therapeutic anti-inflammatory drugs can be dangerous or have no effect at all.131 Improved results can be achieved by identifying specific biomarkers, allowing for more precise targeting of therapy techniques that were previously ineffective and more selective patient selection. However, it is unlikely that the current set of physiological indicators will provide appropriate diagnostic and prognostic signals.

ImmunologySome claim that as compared to traditional clinical monitoring, immunomonitoring has no advantages. An immunoinflammatory biomarker is beneficial when it can provide information beyond what can be obtained from a typical physiological examination. This information guarantees that therapy can be beneficial before the end of the treatment time. Given the complex immunoinflammatory response associated with sepsis, it is critical to look at symptoms from a range of perspectives. Procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are a few examples of inflammatory biomarkers that have been studied in conjunction with human sepsis to learn more about their diagnostic utility and possible relationship to mortality.132 PCT has shown great promise as a diagnostic marker in distinguishing sepsis from noninfectious SIRS etiology. Because PCT has a comparable effect on septic animal survival, it has also been studied as a possible target for therapeutic therapies. However, higher death rates were the outcome of neutralizing calcitonin precursors. The use of PCT in critical care settings is the subject of ongoing research. Furthermore, several clinical trials are also being conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of PCT immunomonitoring in sepsis patients. The possible effects of daily PCT levels on patient outcomes are presently being studied. The goal of the PASS study, which is filed under the NCT00271752, is to obtain important information in this field. You can visit http://www.clinicaltrials.gov for additional information. Daily PCT levels may shorten the duration of antimicrobial therapy (Pro-SEPS trial; NCT01025180) and offer helpful information for treatment decisions in septic patients (SISPCT study; NCT00832039). The usefulness of IL-6 as a biomarker for sepsis is still debatable. Opinions on its function vary; some consider it to be little more than a disease marker, while others think it is essential in assessing the severity of the sickness.133 Nevertheless, IL-6 strongly predicts septic complications and mortality in both animal and human models. CRP in sepsis has little predictive and diagnostic significance because of its low specificity.134

Besides the extensive studies on humoral markers, scientists have also found that sepsis patients have significant changes in immunoinflammatory responses in cellular compartments, particularly leukocytes.135 The goal of the research was to assess a variety of sepsis-related biochemical indicators without needless duplication. A relationship was discovered between the patient's immunological status and the monocytes’ expression of the fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) and HLA-DR. Patients’ expression levels dropped when they experienced immunosuppression due to clinical sepsis.136 Studies have demonstrated a strong association between a lower lymphocyte count in sepsis patients and a poor outcome. Studies have shown that preventing lymphocyte apoptosis in animal cases of sepsis significantly increased survival rates.137 It has been found that sepsis outcome in hospitalized patients can be accurately predicted by measuring the proportion of neutrophils expressing CD64. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells in septic patients can give important information about the stage and severity of the illness.138

ImmunomonitoringBiomarker-based immunomonitoring is a versatile method used in various preventive and disease scenarios. When examining sepsis, the main focus has been on prognosis and diagnosis. In addition, previous studies have been conducted to determine if biomarkers can help in the timely discontinuation of antibiotics. When evaluating the effectiveness of a biomarker for sepsis diagnosis, it is important to consider various performance indicators. These include reducing the time it takes to make a diagnosis, improving the ability to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections, determining whether inflammation is caused by an infectious or noninfectious source, and assessing the effectiveness of infection control measures.139 The first two factors are extremely important because prompt intervention greatly enhances the outlook for patients suffering from sepsis. In the realm of medical research, there is a constant pursuit of innovative approaches. However, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of promptly administering antibiotics in the early stages of sepsis treatment. Patients suffering from septic shock experienced a significant decrease in survival rates when effective antibiotic treatment was delayed, with a decline of 8% for every additional hour of delay.140 In comparison to the widely accepted blood culture and SIRS criterion, biomarkers are expected to reduce the waiting time in this critical period. While the overall goal is practical, there is a significant limitation: it only identifies sepsis, not infection. Various biomarker-based tests, both experimental and commercial, can assist in detecting bacterial infections in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. However, it is important to note that these tests do not provide information about the pathogen's susceptibility to antibiotics or identify the specific causative pathogen. Insufficient administration of antibiotics in the early stages of sepsis has been associated with a significant decrease in the chances of survival. Consequently, omitting this crucial treatment may jeopardize the well-being of patients.141 By integrating biomarker-based monitoring with advanced molecular techniques, like nucleic acid-based technologies that can detect specific diseases, we may be able to fill this diagnostic gap. It is possible that a biomarker could have provided early warning signs of sepsis before the patient experienced hypotension. Ideally, this would have helped with timely and suitable intervention, thus preventing the patient's deterioration into severe sepsis. It appears that biomarkers have a significantly greater ability to predict and guide treatment than diagnostic methods. In contrast to APACHE or SOFA scores, immunomonitoring effectively identified the group at high risk and the varying immune response, allowing for more personalized and targeted treatment approaches. Serial biomarker measurements have been thoroughly examined in animal models and septic patients,142 indicating they are the more cautious in this situation. Customizing treatment for septic patients based on their immunoinflammatory condition is a relatively new advancement. There is a notable connection between early sepsis mortality and an excessive hyperinflammatory response. Interestingly, the characteristic features of hyperinflammatory and hypo-inflammatory reactions in this condition are remarkably similar. A thorough analysis has found that providing certain immunomodulators to a specific group of critically ill septic patients can greatly improve their chances of survival. This approach has been utilized in clinical trials with varying levels of effectiveness: A study conducted on patients with a higher risk of mortality, as indicated by the biomarker IL-6, found that treatment with anti-TNF antibodies showed a slight improvement in survival rates. However, this advantage was observed in only one out of the two studies.143 The lack of consensus on accurately characterising immune-inflammatory signatures in different septic patients remains a significant challenge in advancing this field. Nevertheless, sepsis in experimental animals demonstrated the successful utilization of a biomarker to guide general treatments, like glucocorticoids, and enhance survival.144 Various subtypes of sepsis can result in different clinical outcomes. Sepsis is commonly diagnosed by assessing a localized infection, such as peritonitis, pneumonia, or abscesses. Regarding disease diagnosis and predicting clinical progression, it might be more beneficial to measure inflammatory markers at the site of infection rather than in plasma. According to research, local manifestations of infection occur before systemic changes. The intraperitoneal micro dialysis data noted significant elevation in lactate pyruvate ratios following an urgent laparotomy.145 In this study, it was observed that there was no correlation between peritoneal cytokine levels and plasma levels after major surgery, even though the former were higher than the latter. A highly accurate identification of pneumonia patients in the lungs was achieved by enhancing soluble triggering receptor on myeloid cells 1 expression during Mini bronchoalveolar lavage.146 Although monitoring local biomarker levels can have advantages, it may not always be possible or practical. In most cases, peripheral blood is the easiest specimen to obtain for diagnostic purposes.147

Prediction paradigmsBiomarkers have a great chance of being useful if they exceed current physiological scoring systems. Numerous investigations have directly compared the diagnostic accuracy of physiological scoring systems and biomarkers. The analysis entailed determining the receiver operator characteristic's area under the curve using the provided data. The biomarkers perform at a level comparable to, or even higher than, that of the scoring systems. Researchers discovered contradictory findings in a recent study148 about the predictive efficacy of several biomarkers for sepsis. It was discovered that PCT performed noticeably better than CRP, and IL-6 even performed even better. However, in contrast to the previous study149 there was no discernible variation in the blood plasma levels of IL-6 between patients who had SIRS following surgery and those who did not. It is interesting to note that the ratio of TNF to IL-10 was found to possess predictive significance. According to earlier studies, people with septic shock or severe sepsis had greater PCT levels than people with sepsis alone. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that IL-10 and TNF are more reliable death indicators.

Ninety-four individuals were included in a comprehensive study aimed at identifying the best reliable indicators for sepsis death prediction. To guarantee thorough results, a wide range of characteristics were explored in the study. Initial research showed that IL-6 and TNF-soluble receptor I levels were correlated with death. Subsequent analysis of several variables, including age and APACHE II, showed that the early plasma IL-6 concentrations are the sole consistent predictor of 28-day mortality.150 Natriuretic peptide plasma levels and APACHE II scores in sepsis patients appear to be related, suggesting that these levels may have use as biomarkers.112 A study was done to look at the relationship between hospital mortality, physiologic scores, and brain natriuretic protein (BNP) levels. Both BNP and SAPS II (the new simplified acute physiology score) were proven to be independent variables that potentially predict mortality in a hospital setting by a logistic regression analysis.151 The results of a study on PCT and SOFA score levels indicated that both variables had comparable predictive power. But by day three, the SOFA score correctly predicted the result, and by day six following admission, the PCT demonstrated a good predictive capacity.144

Modern markers and approachesAdditional investigation is necessary to ascertain the optimal biomarkers and their efficacy in various scenarios. Recent research has put forward a range of potential new biomarkers. Pro-BNP is a reliable indicator of mortality152 and has shown a strong correlation with survival in individuals diagnosed with severe sepsis and septic shock. During the sepsis examination, two biomarkers attracted attention: high mobility group box 1 and an abnormal late rise in restin.153 According to the analysis, high mobility group box 1 consistently showed higher plasma concentration levels than cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF. An kinetic analysis was utilized to determine this.154 This discovery highlights the significant clinical relevance of the biomarker. In addition, it has been noted that sepsis-related mortality is linked to higher plasma concentrations of tissue inhibitors, and individuals with sepsis show raised levels of matrix metalloproteinases.155 There is an interesting correlation between the levels of gelsolin and interalpha inhibitor protein in the bloodstream and the severity of illness in septic patients. Based on a previous study, it was found that the indicator showed a high level of accuracy (area under the curve of 0.89) in differentiating between sepsis and noninfectious SIRS in critically ill patients. This presents a significant difference compared to a previous indicator. Plasma concentrations of selenium or selenoprotein P can be valuable prognostic markers in critically ill patients.156 It suggests that physiological activity may not be necessary for biomarkers to provide valuable data. Considering the wide range of septic conditions, conducting medical case studies in a controlled setting can reveal new and promising indicators, enhancing the accuracy of sepsis diagnosis and prediction. There is a possibility of sepsis occurring in individuals who have undergone multiple traumas without any traumatic brain injury. It is important to consider the levels of Pro-C-type natriuretic peptide157 in this case. When examining newborn sepsis, it was discovered that serum amyloid A proved to be more reliable and accurate in both diagnosis and monitoring, surpassing PCT and CRP. The timely identification of inflammation proved extremely beneficial as it led to a faster diagnosis of the condition.158

The challenges in evaluating a patient's severity during the initial phases of goal-directed therapy are elucidated.159 This study revealed a concerning trend where the severity of sepsis was often underestimated in emergency rooms. Using SIRS criteria alone is not enough to assess the progression of non-life-threatening illnesses, such as community-acquired pneumonia, to severe sepsis, septic shock, and mortality. To address these limitations, researchers160 have utilized advanced data analysis techniques, such as artificial neural networks, to accurately identify the specific group of septic patients facing the highest mortality risk shortly after admission to the ER. A team of researchers conducted a study using mathematical models to predict their patients’ progress. A comprehensive study used a Monte Carlo microsimulation model to predict the sequential SOFA scores, in-hospital death rates, and hospital discharges for sepsis patients.161 These findings highlight the significance of the duration of the illness in forecasting the outcome of sepsis.

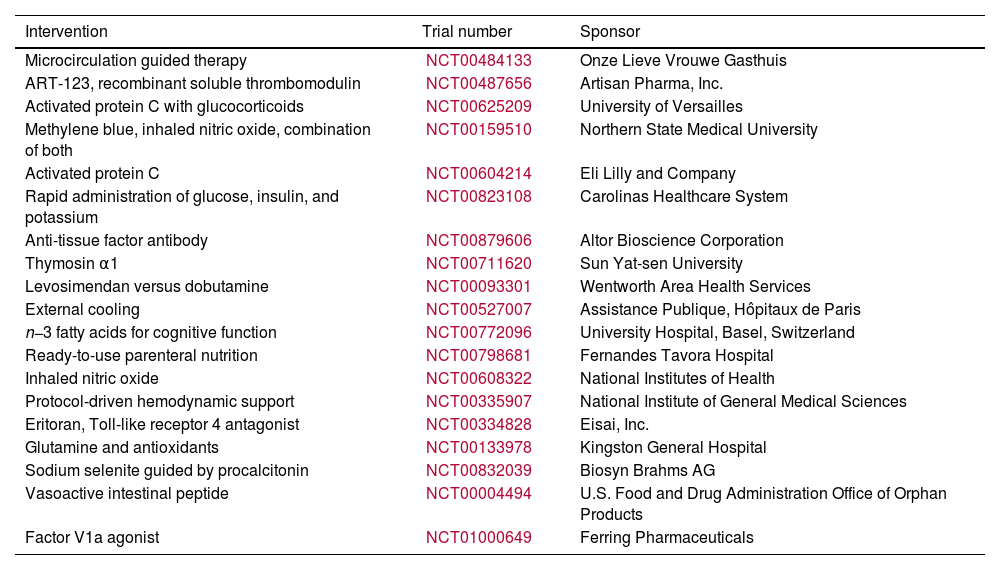

Modern therapeutic measuresVarious pathogenic factors of sepsis have been discovered, resulting in the development of several treatment options to improve survival rates. In February 2010, the sepsis trials listed on http://www.clinicaltrials.gov are displayed in Table 1. Efforts were made to counteract substances that trigger an exaggerated inflammatory response. Monoclonal antibodies specifically targeted TNF, IL-1 receptors, and endotoxin antibodies. However, despite these efforts, there was no noticeable improvement in survival. These results highlight the intricate and interconnected nature of the immune system's innate defenses in cases of sepsis. Prior attempts to reduce inflammation with high-dose steroids have not improved survival.162 Decreasing the number of steroids administered, specifically 200mg of hydrocortisone per day, did not have any impact on the mortality rate. It is used as an additional treatment for sepsis because it helps speed up the recovery from shock. A growing array of innovative treatments, such as a synthetic antagonist of Toll-like receptor 4, focus on addressing inflammation in its early stages. A recent analysis163 found that this drug's Phase II clinical trial showed no significant decrease in mortality. It is worth mentioning that the group that received the highest dose had a lower fatality rate. Activated protein C is an FDA-approved treatment for sepsis. It is designed to target the microthrombosis that occurs during the disease specifically. Furthermore, its anti-inflammatory properties have been widely acknowledged.164 However, currently, there is insufficient evidence to support this assertion. For more information about this treatment, please refer to the section on coagulation and peritonitis. EGDT does not focus on the microbiological and inflammatory pathophysiology of sepsis. Currently, EGDT is part of the Surviving Sepsis recommendations.165 Extensive clinical trials have shown its effectiveness in reducing mortality rates in severe cases of sepsis and septic shock.166 These recommendations emphasise the importance of providing timely and thorough supportive care to septic patients. These recommendations aim to effectively manage hyperglycemia, minimize the risk of barotrauma associated with mechanical ventilation, address infections, and optimize organ perfusion. Alternative therapeutic methods, like the use of low-dose steroids or activated protein C, may be considered if deemed necessary. The study found that higher adherence to the recommended criteria is associated with lower death rates. This correlation was observed across multiple medical centers.167

Sepsis registered traits.

| Intervention | Trial number | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|

| Microcirculation guided therapy | NCT00484133 | Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis |

| ART-123, recombinant soluble thrombomodulin | NCT00487656 | Artisan Pharma, Inc. |

| Activated protein C with glucocorticoids | NCT00625209 | University of Versailles |

| Methylene blue, inhaled nitric oxide, combination of both | NCT00159510 | Northern State Medical University |

| Activated protein C | NCT00604214 | Eli Lilly and Company |

| Rapid administration of glucose, insulin, and potassium | NCT00823108 | Carolinas Healthcare System |

| Anti-tissue factor antibody | NCT00879606 | Altor Bioscience Corporation |

| Thymosin α1 | NCT00711620 | Sun Yat-sen University |

| Levosimendan versus dobutamine | NCT00093301 | Wentworth Area Health Services |

| External cooling | NCT00527007 | Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris |

| n−3 fatty acids for cognitive function | NCT00772096 | University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland |

| Ready-to-use parenteral nutrition | NCT00798681 | Fernandes Tavora Hospital |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | NCT00608322 | National Institutes of Health |

| Protocol-driven hemodynamic support | NCT00335907 | National Institute of General Medical Sciences |

| Eritoran, Toll-like receptor 4 antagonist | NCT00334828 | Eisai, Inc. |

| Glutamine and antioxidants | NCT00133978 | Kingston General Hospital |

| Sodium selenite guided by procalcitonin | NCT00832039 | Biosyn Brahms AG |

| Vasoactive intestinal peptide | NCT00004494 | U.S. Food and Drug Administration Office of Orphan Products |

| Factor V1a agonist | NCT01000649 | Ferring Pharmaceuticals |

| Resuscitation studies | Trial numbers |

|---|---|

| Colloid (typically albumin) versus crystalloid | NCT00707122, NCT00318942, NCT00327704 |

| Hydroxy-ethyl starch | NCT00962156, NCT00464204, NCT00273728 |

| Antibiotic studies | Trial number |

| Adjusted antibiotic dosing in patients with renal failure | NCT00816790 |

| Meropenem | NCT00534287 |

| Renal dialysis and antibiotics | NCT00451373 |

| Cotrimoxazole versus vancomycin for MRSA | NCT00427076 |

| Duration of antibiotics for peritonitis | NCT00657566 |

| Daptomycin versus vancomycin for MRSA | NCT00770341 |

| Liposome encapsulated amphotericin B | NCT00697944 |

| Azithromycin (macrolide antibiotic) for early therapy | NCT00708799 |

| 30-min versus 3-h infusion of meropenem (antibiotic) | NCT00891423 |

All authors contribute equally and approved final version of manuscript to publish.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.