The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the world, mainly during the first year of the pandemic, where strategies such as vaccination were not available. Information on the outcomes of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in Colombia is scarce. Our main objective was to characterize critically ill patients with COVID-19 in our region.

MethodsWe conducted a single-center retrospective observational study in which we included patients with COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR who were admitted to the adult ICU between March 18, 2020 and March 18, 2021, in Quindío, Colombia. We identify the clinical and laboratory characteristics at admission, the support used, and their relationship with mortality during ICU hospitalization.

ResultsThree hundred and fifty-nine patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 were admitted, 64% men, mean age was 62.7 years (SD±12.3), body mass index 27.9kg/m2 (±5.8), SOFA score was 7.6 (±3.12), Pa/FiO2 96.2 (±62.3), and lung compliance 30.5ml/cmH2O (±18.4). Mortality was 60%. The variables with the highest mortality association were obesity OR: 2.38 (95% CI: 1.39–4.09, p: <.001), Glasgow coma scale at admission <12: 17.5, (5.21–58.8, p: <.001), PaFiO2 <100: 5.63, (3.38–9.39, p: <.001), static lung compliance less than 50ml/cmH2O: 3.54, (3.38–9.39, p: <.001), SOFA score >5: 3.75 (2.19–6.42, p: <0.001), ferritin>1000: 2.58, (1.66–4.02, p: <.001), C-reactive protein>5: 2.52 (1.42–4.26, p: <.001), and LDH>280: 2.71 (1.55–4.74, p: <.001). Patients who required PEEP>10cmH2O: 2.34 (1.48–3.70, p: <.001), FiO2>60%: 4.01, (2.46–6.53, p: <.001), and ventilation in the prone position.

ConclusionMortality in the first year of the pandemic in our region was high, mainly associated with obesity, inflammation, altered mental status upon admission, and increased lung elastance.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha tenido un impacto devastador en el mundo, principalmente durante el primer año de la pandemia, donde no se disponía de estrategias como la vacunación. La información sobre los resultados de los pacientes ingresados en la unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) en Colombia es escasa. Nuestro principal objetivo fue caracterizar a los pacientes críticos con COVID-19 en nuestra región.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio observacional retrospectivo unicéntrico donde incluimos pacientes confirmados con RT-PCR para COVID-19 que ingresaron a la UCI de adultos entre el 18 de marzo de 2020 y el 18 de marzo de 2021 en Quindío, Colombia. Identificamos las características clínicas y de laboratorio al ingreso, los soportes utilizados y su relación con la mortalidad durante la hospitalización en UCI.

ResultadosIngresaron 359 pacientes con diagnóstico confirmado de COVID-19, 64% hombres, edad 62,7años (DE±12,3), índice de masa corporal 27,9kg/m2 (±5,8), SOFA score 7,6 (±3,12), Pa/FiO2 96,2 (±62,3) y distensibilidad pulmonar 30,5ml/cmH2O (±18,4). La mortalidad fue del 60%. Las variables con mayor asociación a mortalidad fueron la obesidad, OR: 2,38 (IC95%: 1,39-4,09, p<0,001), escala de coma de Glasgow al ingreso <12: 17,5 (5,21-58,8, p<0,001), PaFiO2 <100: 5,63 (3,38-9,39, p<0,001), distensibilidad pulmonar estática inferior a 50ml/cmH2O: 3,54 (3,38-9,39, p<0,001), puntuación SOFA >5: 3,75 (2,19-6,42, p<0,001), ferritina >1.000: 2,58 (1,66-4,02, p<0,001), proteína C reactiva >5: 2,52 (1,42-4,26, p<0,001) y LDH >280: 2,71 (1,55-4,74, p<0,001). Pacientes que requirieron PEEP >10cmH2O: 2,34 (1,48-3,70, p<0,001), FiO2 >60%: 4,01 (2,46-6,53, p<0,001) y ventilación en decúbito prono.

ConclusiónLa mortalidad en el primer año de la pandemia en nuestra región fue alta, asociada principalmente a obesidad, inflamación, alteración del estado mental al ingreso y aumento de la elastancia pulmonar.

Emerging infections are a real challenge for health personnel. Currently, SARS-CoV-2 has shown an infectious dynamic that still has the world on alert after more than a year and a half of the pandemic,1,2 with more than 560 million infected patients and more than 6 million deaths, up to July 15, 2022.3

There are 1119 municipalities with COVID-19 cases in Colombia, which corresponds to 99% of the territory. As of September 21, 2021, 4.9 million people have been infected, and about 126,000 patients have died from COVID-19.4,5 To face this crisis, the country has increased its installed beds, currently having 46,368 hospital beds, 3795 intermediate care beds and 11,450 intensive care beds.6,7

Quindío, a small state located in the center of Colombia, has approximately 500,000 inhabitants and has 563 available hospital beds, 53 intermediate care beds and 150 ICU beds. 85% (480) of hospital beds are concentrated in the capital city (Armenia), 100% of unique care beds. Total number of ICU beds represent 300% growth in installed intensive care capacity since the onset of the pandemic.7

In the literature, some works account for the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients infected with SARS-COV-2 in Asian populations,8 European9–11 and American populations.12 For example, 20% of patients require admission to the ICU due to critical illness; cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes are risk factors for severe disease and unfavorable outcomes.13 In addition, 17% of patients require mechanical ventilation, with men more likely than women to receive ventilatory support (22% versus 12%). Ventilated patients have a mean duration of mechanical ventilation of 12 days and 18 days of hospitalization. The mortality of ventilated patients was 53%.10

In Latin America, the information scarce.14–16 For example, not much information is available in Colombia, where most of the population is different from the Asian, European, and Anglo-Saxon. The existing one is from studies of short duration or with small samples,17 which leaves us with a knowledge gap at the national level regarding the characteristics, management, and outcomes of critically ill patients due to COVID-19 who are admitted to the ICU as adults.

This study aimed to identify the baseline characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients infected with SARS-COV-2 in critical condition who were hospitalized in the ICU of the San Juan de Dios regional hospital in the first year of the pandemic.

MethodsStudy designThis is an observational, retrospective, single-center study.

SettingsIt was carried out in the intensive care unit of the regional hospital of Quindío San Juan de Dios; this is the leading and most prominent university health center in the state, it currently has 304 beds, of which 18 are intensive care for adult patients with COVID-19 and 56 unique care beds, built progressively since the beginning of the pandemic as an ICU extension.

The ICU is attended 24h a day by two intensive care physicians, two nursing professionals, two respiratory therapy professionals, six nursing assistants, a speech therapist, a physiotherapist, and a nutritionist.

The data was analyzed for the corresponding period between March 18, 2020, and March 18, 2021.

ParticipantsDescribe the data related to patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 by RT-PCR in any of its manifestations of the spectrum of the disease who have been admitted to the ICU as adults during the period studied.

VariablesAnthropometric variables, comorbidities, admission manifestations, disease severity are described using the SOFA score, ventilatory strategies, pulmonary mechanics, use of prone position, oxygenation disorder (severity), the phenotype of pulmonary manifestations (L–H), internal environment variables (renal function, electrolytes), inflammation variables (C-reactive protein, lactic dehydrogenase, ferritin). Coagulation variables (platelets – D-dimer), myocardial injury variables (troponin I), as well as the use of hemodynamic support drugs, antibiotics, sedatives, analgesics and neuromuscular relaxants, anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory drugs, outcome variables (mortality).

Source of informationA database was prospectively completed in a spreadsheet (Excel®) from patient one to the cut-off date of the study.

Bias controlThe database has all the variables in analysis; It has no loss of information; it was completed in real-time by an intensivist (CASP) and verified by two intensivists (WCO-YDG).

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed in SPSS 27® (IBM, USA). The qualitative variables are summarized with proportions and the quantitative variables with measures of central tendency and dispersion. Normality was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Association measures (Odds Ratio) and χ2 were performed to compare the categorical variables. Statistical significance will be expressed as a function of p. <0.05.

Ethical aspectsThe bioethics committee approved this study of the San Juan de Dios University Hospital, Armenia, Quindío, Colombia, with registration No.: 02461/21.

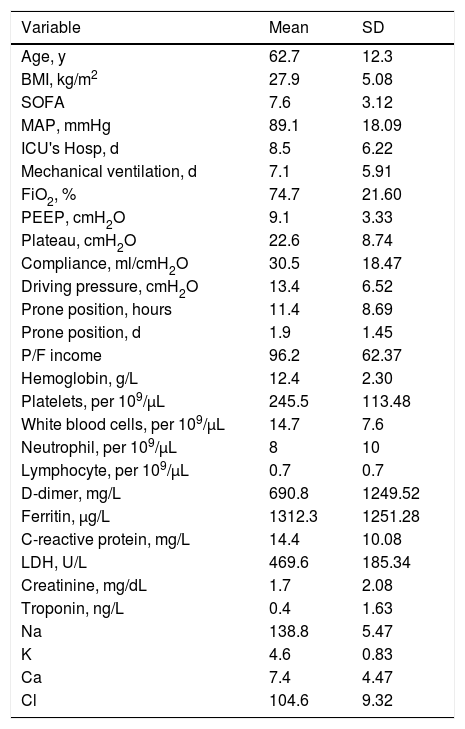

ResultsIn total, 359 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 were admitted, 232 men (64%), the mean age was 62.7 years (SD: ±12.3), the body mass index (BMI) was 27.9kg/m2 (SD: ±5.8), the mean of the SOFA score (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) was 7.6 (SD: ±3.12), the mean of Pa/FiO2 and lung compliance at admission were low (96.2, SD: ±62.3) and (30.5ml/cmH2O, SD: ±18.4) respectively. On the other hand, inflammation variables were high at admission: Ferritin (1312μg/L, DS: ±1251.2), C-reactive protein (14.4mg/L, DS: ±10), lactic dehydrogenase (469.6U/L, DS: ±185.3) as shown in Table 1.

Quantitative variables of the patients at admission.

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.7 | 12.3 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.9 | 5.08 |

| SOFA | 7.6 | 3.12 |

| MAP, mmHg | 89.1 | 18.09 |

| ICU's Hosp, d | 8.5 | 6.22 |

| Mechanical ventilation, d | 7.1 | 5.91 |

| FiO2, % | 74.7 | 21.60 |

| PEEP, cmH2O | 9.1 | 3.33 |

| Plateau, cmH2O | 22.6 | 8.74 |

| Compliance, ml/cmH2O | 30.5 | 18.47 |

| Driving pressure, cmH2O | 13.4 | 6.52 |

| Prone position, hours | 11.4 | 8.69 |

| Prone position, d | 1.9 | 1.45 |

| P/F income | 96.2 | 62.37 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 12.4 | 2.30 |

| Platelets, per 109/μL | 245.5 | 113.48 |

| White blood cells, per 109/μL | 14.7 | 7.6 |

| Neutrophil, per 109/μL | 8 | 10 |

| Lymphocyte, per 109/μL | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 690.8 | 1249.52 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 1312.3 | 1251.28 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 14.4 | 10.08 |

| LDH, U/L | 469.6 | 185.34 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.7 | 2.08 |

| Troponin, ng/L | 0.4 | 1.63 |

| Na | 138.8 | 5.47 |

| K | 4.6 | 0.83 |

| Ca | 7.4 | 4.47 |

| Cl | 104.6 | 9.32 |

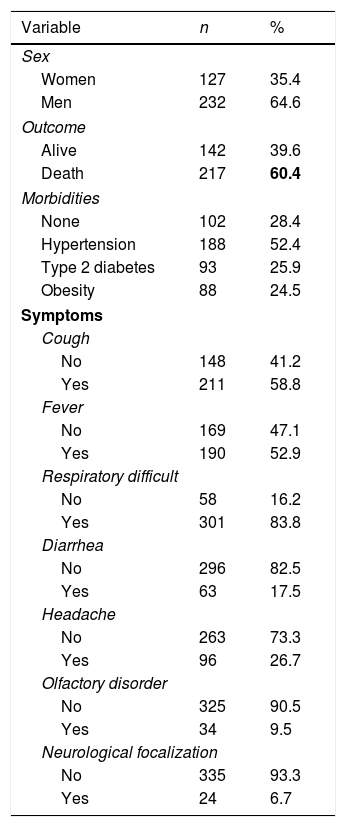

The most frequent symptoms were cough (58.8%) and respiratory distress (83.8%), hypertension was the most prevalent morbidity (52.4%), most of the patients required mechanical ventilation (90.3%), and in 88.3% of the cases, the assisted-controlled ventilation mode was used.

88.3% of the patients required sedation and 66.3% neuromuscular relaxation; 97.2% received anticoagulants, 86.4% corticosteroids, 94.2% antibiotics, and less than a third of the patients required vasoactive drugs (28.7%). Unfortunately, 60% of patients admitted to the adult ICU for COVID-19 died (Tables 2 and 3).

Qualitative characteristics at admission.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Women | 127 | 35.4 |

| Men | 232 | 64.6 |

| Outcome | ||

| Alive | 142 | 39.6 |

| Death | 217 | 60.4 |

| Morbidities | ||

| None | 102 | 28.4 |

| Hypertension | 188 | 52.4 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 93 | 25.9 |

| Obesity | 88 | 24.5 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Cough | ||

| No | 148 | 41.2 |

| Yes | 211 | 58.8 |

| Fever | ||

| No | 169 | 47.1 |

| Yes | 190 | 52.9 |

| Respiratory difficult | ||

| No | 58 | 16.2 |

| Yes | 301 | 83.8 |

| Diarrhea | ||

| No | 296 | 82.5 |

| Yes | 63 | 17.5 |

| Headache | ||

| No | 263 | 73.3 |

| Yes | 96 | 26.7 |

| Olfactory disorder | ||

| No | 325 | 90.5 |

| Yes | 34 | 9.5 |

| Neurological focalization | ||

| No | 335 | 93.3 |

| Yes | 24 | 6.7 |

Statistically significant results are highlighted in bold.

Treatments used for the patients.

| Treatment | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical ventilatory mode | ||

| None | 35 | 9.7 |

| ACV | 317 | 88.3 |

| ACP | 5 | 1.4 |

| PRVC | 1 | 0.3 |

| Duolevel | 1 | 0.3 |

| Sedation and analgesia | ||

| Fentanyl | 317 | 88.3 |

| Midazolam | 224 | 62 |

| Propofol | 5 | 1.4 |

| Dexmedetomidine | 6 | 1.7 |

| Muscular relaxant | ||

| None | 121 | 33.7 |

| Rocuronium | 230 | 64.1 |

| Cisatracurio | 8 | 2.2 |

| Anticoagulation/prophylaxis | ||

| No | 10 | 2.8 |

| Yes | 349 | 97.2 |

| Corticoids | ||

| No | 49 | 13.6 |

| Yes | 310 | 86.4 |

| Antibiotics | ||

| None | 21 | 5.8 |

| Meropenem | 44 | 12.3 |

| Pip/tazobactam | 130 | 36.2 |

| Cefepime | 18 | 5 |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 113 | 31.5 |

| Vancomycin | 33 | 9.2 |

| Macrolides | 158 | 44 |

| RBC transfusion | ||

| No | 352 | 98.1 |

| Yes | 7 | 1.9 |

| Nutritional support | ||

| None | 32 | 8.9 |

| Enteral | 326 | 90.8 |

| Parenteral | 1 | 0.3 |

| Vasoactive/inotropic | ||

| None | 256 | 71.3 |

| Norepinephrine | 98 | 27.3 |

| Vasopressin | 3 | 0.8 |

| Dobutamine | 2 | 0.6 |

| Renal support | ||

| No | 317 | 88.3 |

| Yes | 42 | 11.7 |

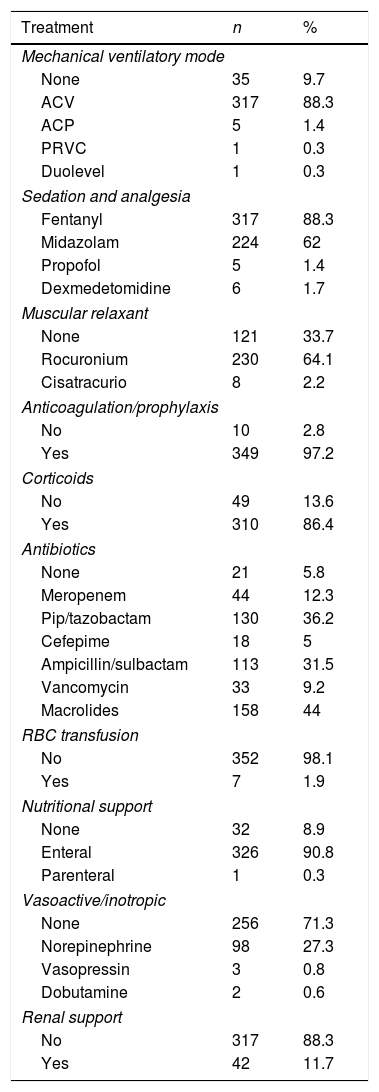

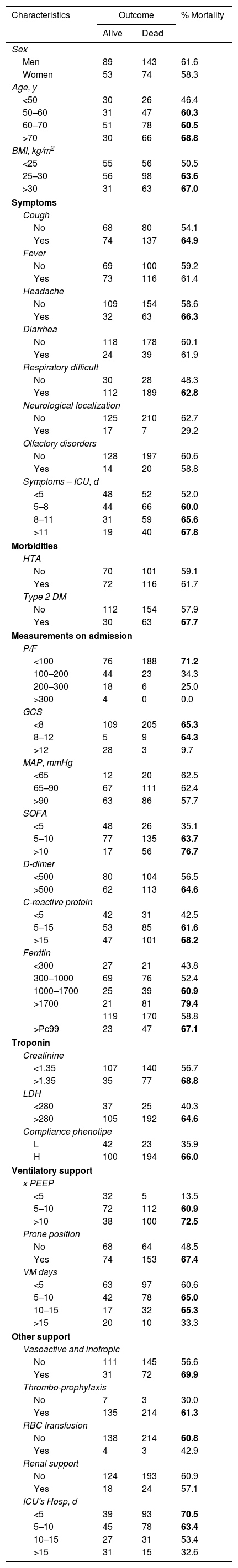

Mortality in men was slighter (61.6% vs. 58.3%), lower in patients under 50 years of age (46.4%), and with a normal body mass index (50.5%). Mortality was higher when admission symptoms were cough (64.9%), headache (63.3%), and respiratory distress (62.8%) (Table 4).

Variables and mortality.

| Characteristics | Outcome | % Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Dead | ||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 89 | 143 | 61.6 |

| Women | 53 | 74 | 58.3 |

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 30 | 26 | 46.4 |

| 50–60 | 31 | 47 | 60.3 |

| 60–70 | 51 | 78 | 60.5 |

| >70 | 30 | 66 | 68.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| <25 | 55 | 56 | 50.5 |

| 25–30 | 56 | 98 | 63.6 |

| >30 | 31 | 63 | 67.0 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Cough | |||

| No | 68 | 80 | 54.1 |

| Yes | 74 | 137 | 64.9 |

| Fever | |||

| No | 69 | 100 | 59.2 |

| Yes | 73 | 116 | 61.4 |

| Headache | |||

| No | 109 | 154 | 58.6 |

| Yes | 32 | 63 | 66.3 |

| Diarrhea | |||

| No | 118 | 178 | 60.1 |

| Yes | 24 | 39 | 61.9 |

| Respiratory difficult | |||

| No | 30 | 28 | 48.3 |

| Yes | 112 | 189 | 62.8 |

| Neurological focalization | |||

| No | 125 | 210 | 62.7 |

| Yes | 17 | 7 | 29.2 |

| Olfactory disorders | |||

| No | 128 | 197 | 60.6 |

| Yes | 14 | 20 | 58.8 |

| Symptoms – ICU, d | |||

| <5 | 48 | 52 | 52.0 |

| 5–8 | 44 | 66 | 60.0 |

| 8–11 | 31 | 59 | 65.6 |

| >11 | 19 | 40 | 67.8 |

| Morbidities | |||

| HTA | |||

| No | 70 | 101 | 59.1 |

| Yes | 72 | 116 | 61.7 |

| Type 2 DM | |||

| No | 112 | 154 | 57.9 |

| Yes | 30 | 63 | 67.7 |

| Measurements on admission | |||

| P/F | |||

| <100 | 76 | 188 | 71.2 |

| 100–200 | 44 | 23 | 34.3 |

| 200–300 | 18 | 6 | 25.0 |

| >300 | 4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| GCS | |||

| <8 | 109 | 205 | 65.3 |

| 8–12 | 5 | 9 | 64.3 |

| >12 | 28 | 3 | 9.7 |

| MAP, mmHg | |||

| <65 | 12 | 20 | 62.5 |

| 65–90 | 67 | 111 | 62.4 |

| >90 | 63 | 86 | 57.7 |

| SOFA | |||

| <5 | 48 | 26 | 35.1 |

| 5–10 | 77 | 135 | 63.7 |

| >10 | 17 | 56 | 76.7 |

| D-dimer | |||

| <500 | 80 | 104 | 56.5 |

| >500 | 62 | 113 | 64.6 |

| C-reactive protein | |||

| <5 | 42 | 31 | 42.5 |

| 5–15 | 53 | 85 | 61.6 |

| >15 | 47 | 101 | 68.2 |

| Ferritin | |||

| <300 | 27 | 21 | 43.8 |

| 300–1000 | 69 | 76 | 52.4 |

| 1000–1700 | 25 | 39 | 60.9 |

| >1700 | 21 | 81 | 79.4 |

| 119 | 170 | 58.8 | |

| >Pc99 | 23 | 47 | 67.1 |

| Troponin | |||

| Creatinine | |||

| <1.35 | 107 | 140 | 56.7 |

| >1.35 | 35 | 77 | 68.8 |

| LDH | |||

| <280 | 37 | 25 | 40.3 |

| >280 | 105 | 192 | 64.6 |

| Compliance phenotipe | |||

| L | 42 | 23 | 35.9 |

| H | 100 | 194 | 66.0 |

| Ventilatory support | |||

| x PEEP | |||

| <5 | 32 | 5 | 13.5 |

| 5–10 | 72 | 112 | 60.9 |

| >10 | 38 | 100 | 72.5 |

| Prone position | |||

| No | 68 | 64 | 48.5 |

| Yes | 74 | 153 | 67.4 |

| VM days | |||

| <5 | 63 | 97 | 60.6 |

| 5–10 | 42 | 78 | 65.0 |

| 10–15 | 17 | 32 | 65.3 |

| >15 | 20 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Other support | |||

| Vasoactive and inotropic | |||

| No | 111 | 145 | 56.6 |

| Yes | 31 | 72 | 69.9 |

| Thrombo-prophylaxis | |||

| No | 7 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Yes | 135 | 214 | 61.3 |

| RBC transfusion | |||

| No | 138 | 214 | 60.8 |

| Yes | 4 | 3 | 42.9 |

| Renal support | |||

| No | 124 | 193 | 60.9 |

| Yes | 18 | 24 | 57.1 |

| ICU's Hosp, d | |||

| <5 | 39 | 93 | 70.5 |

| 5–10 | 45 | 78 | 63.4 |

| 10–15 | 27 | 31 | 53.4 |

| >15 | 31 | 15 | 32.6 |

Statistically significant results are highlighted in bold.

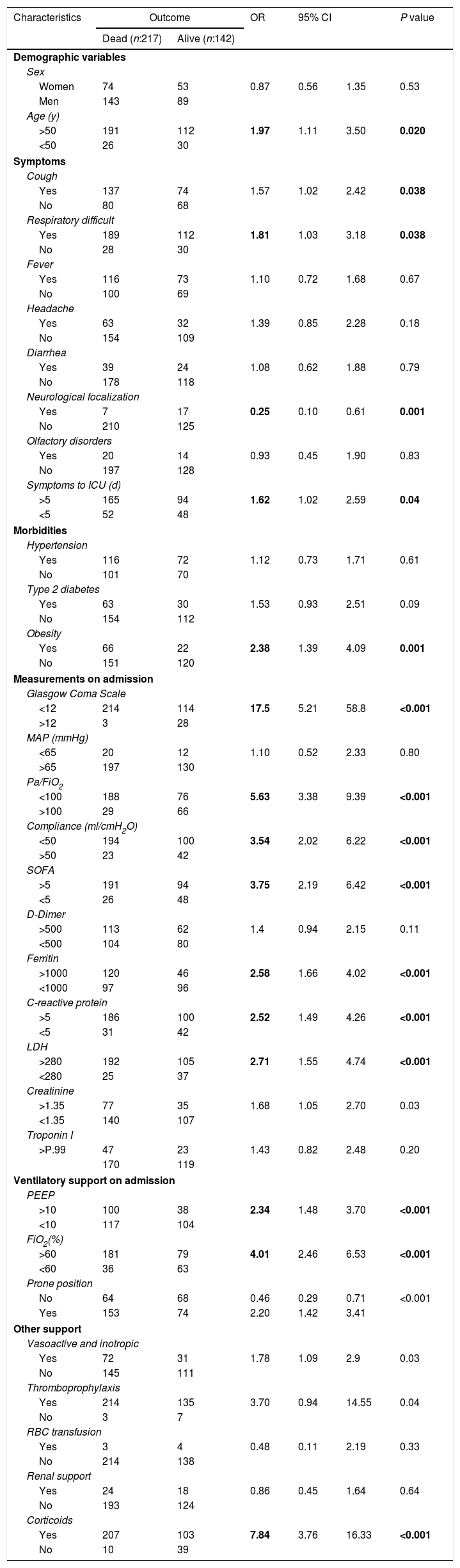

The variables with the highest mortality association were age over 50 years (OR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.11–3.50, p: 0.020), presence of respiratory distress (OR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.03–3.18, p: 0.038), obesity was the morbidity mostly associated with mortality (OR: 2.38, 95% CI: 1.39–4.09, p: <0.001). The measurements at admission that are most associated with mortality were the Glasgow coma scale <12 (OR: 17.5, 95% CI: 5.21–58.8, p: <0.001), PaFiO2<100 (OR: 5.63, 95% CI: 3.38–9.39, p: <0.001), static lung compliance less than 50ml/cmH2O (OR: 3.54, 95% CI: 3.38–9.39, p: <0.001), SOFA score>5 (OR: 3.75, 95% CI: 2.19–6.42, p: <0.001), ferritin>1000 (OR: 2.58, 95% CI: 1.66–4.02, p: <0.001), C-reactive protein>5 (OR: 2.52, 95% CI: 1.42–4.26, p: <0.001), and LDH>280 (OR: 2.71, 95% CI: 1.55–4.74, p: <0.001).

Regarding respiratory supports, patients who required PEEP>10cmH2O (OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.48–3.70, p: <0.001), FiO2>60% (OR: 4.01, 95% CI: 2.46–6.53, p: <0.001) and ventilation in the prone position had a greater association with mortality (Table 5).

Association between variables and mortality.

| Characteristics | Outcome | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead (n:217) | Alive (n:142) | |||||

| Demographic variables | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 74 | 53 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 1.35 | 0.53 |

| Men | 143 | 89 | ||||

| Age (y) | ||||||

| >50 | 191 | 112 | 1.97 | 1.11 | 3.50 | 0.020 |

| <50 | 26 | 30 | ||||

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Cough | ||||||

| Yes | 137 | 74 | 1.57 | 1.02 | 2.42 | 0.038 |

| No | 80 | 68 | ||||

| Respiratory difficult | ||||||

| Yes | 189 | 112 | 1.81 | 1.03 | 3.18 | 0.038 |

| No | 28 | 30 | ||||

| Fever | ||||||

| Yes | 116 | 73 | 1.10 | 0.72 | 1.68 | 0.67 |

| No | 100 | 69 | ||||

| Headache | ||||||

| Yes | 63 | 32 | 1.39 | 0.85 | 2.28 | 0.18 |

| No | 154 | 109 | ||||

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| Yes | 39 | 24 | 1.08 | 0.62 | 1.88 | 0.79 |

| No | 178 | 118 | ||||

| Neurological focalization | ||||||

| Yes | 7 | 17 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.001 |

| No | 210 | 125 | ||||

| Olfactory disorders | ||||||

| Yes | 20 | 14 | 0.93 | 0.45 | 1.90 | 0.83 |

| No | 197 | 128 | ||||

| Symptoms to ICU (d) | ||||||

| >5 | 165 | 94 | 1.62 | 1.02 | 2.59 | 0.04 |

| <5 | 52 | 48 | ||||

| Morbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 116 | 72 | 1.12 | 0.73 | 1.71 | 0.61 |

| No | 101 | 70 | ||||

| Type 2 diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 63 | 30 | 1.53 | 0.93 | 2.51 | 0.09 |

| No | 154 | 112 | ||||

| Obesity | ||||||

| Yes | 66 | 22 | 2.38 | 1.39 | 4.09 | 0.001 |

| No | 151 | 120 | ||||

| Measurements on admission | ||||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | ||||||

| <12 | 214 | 114 | 17.5 | 5.21 | 58.8 | <0.001 |

| >12 | 3 | 28 | ||||

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||||

| <65 | 20 | 12 | 1.10 | 0.52 | 2.33 | 0.80 |

| >65 | 197 | 130 | ||||

| Pa/FiO2 | ||||||

| <100 | 188 | 76 | 5.63 | 3.38 | 9.39 | <0.001 |

| >100 | 29 | 66 | ||||

| Compliance (ml/cmH2O) | ||||||

| <50 | 194 | 100 | 3.54 | 2.02 | 6.22 | <0.001 |

| >50 | 23 | 42 | ||||

| SOFA | ||||||

| >5 | 191 | 94 | 3.75 | 2.19 | 6.42 | <0.001 |

| <5 | 26 | 48 | ||||

| D-Dimer | ||||||

| >500 | 113 | 62 | 1.4 | 0.94 | 2.15 | 0.11 |

| <500 | 104 | 80 | ||||

| Ferritin | ||||||

| >1000 | 120 | 46 | 2.58 | 1.66 | 4.02 | <0.001 |

| <1000 | 97 | 96 | ||||

| C-reactive protein | ||||||

| >5 | 186 | 100 | 2.52 | 1.49 | 4.26 | <0.001 |

| <5 | 31 | 42 | ||||

| LDH | ||||||

| >280 | 192 | 105 | 2.71 | 1.55 | 4.74 | <0.001 |

| <280 | 25 | 37 | ||||

| Creatinine | ||||||

| >1.35 | 77 | 35 | 1.68 | 1.05 | 2.70 | 0.03 |

| <1.35 | 140 | 107 | ||||

| Troponin I | ||||||

| >P.99 | 47 | 23 | 1.43 | 0.82 | 2.48 | 0.20 |

| 170 | 119 | |||||

| Ventilatory support on admission | ||||||

| PEEP | ||||||

| >10 | 100 | 38 | 2.34 | 1.48 | 3.70 | <0.001 |

| <10 | 117 | 104 | ||||

| FiO2(%) | ||||||

| >60 | 181 | 79 | 4.01 | 2.46 | 6.53 | <0.001 |

| <60 | 36 | 63 | ||||

| Prone position | ||||||

| No | 64 | 68 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.71 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 153 | 74 | 2.20 | 1.42 | 3.41 | |

| Other support | ||||||

| Vasoactive and inotropic | ||||||

| Yes | 72 | 31 | 1.78 | 1.09 | 2.9 | 0.03 |

| No | 145 | 111 | ||||

| Thromboprophylaxis | ||||||

| Yes | 214 | 135 | 3.70 | 0.94 | 14.55 | 0.04 |

| No | 3 | 7 | ||||

| RBC transfusion | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 4 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.33 |

| No | 214 | 138 | ||||

| Renal support | ||||||

| Yes | 24 | 18 | 0.86 | 0.45 | 1.64 | 0.64 |

| No | 193 | 124 | ||||

| Corticoids | ||||||

| Yes | 207 | 103 | 7.84 | 3.76 | 16.33 | <0.001 |

| No | 10 | 39 | ||||

Statistically significant results are highlighted in bold.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study on the characteristics and outcomes of adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU in Colombia, a lower-middle-income Latin American country. In this study, most patients were men over 60 years of age, hypertensive and overweight; it was like that found in other Latin American studies. In a Mexican study, the average age of patients admitted to the ICU was 57 years, the body mass index (BMI) was 30.7kg/m2 (± 5.5), and 63% of the patients had a history of hypertension,15 and in an Argentine study, the median was 62 years, the BMI was 29kg/m2,26–31 and 47% of patients were hypertensive.16 In a Colombian study it was found that in seriously ill patients the age, on average, was 59.3 years, the BMI was 26.4kg/m2 and 54.5% of the patients had a history of hypertension.17 In another Colombian study, a median age of 62 years, BMI of 26.7, SOFA score of 5, and mortality between 20% and 88% were found. Characteristics associated with mortality were age, use of vasopressors, and the need for renal replacement therapy.18

The most frequent clinical manifestations were cough and respiratory distress, which is consistent with the published literature.9,13,19,20 The oxygenation disorder was severe, and the static compliance was low, this has been published in other studies and that in fact represents a higher risk of mortality and difficulty in ventilatory management due to the decrease in lung compliance and the requirements of deep sedation and neuromuscular relaxation.19,21,22

Critically ill patients with COVID-19 require admission to the intensive care unit, for airway management, support with invasive mechanical ventilation and in more severe cases for assistance with extracorporeal oxygenation (ECMO).13,23,24 In our work, invasive mechanical ventilation was used in most cases, with an average time of 7.1 days, and the most used mode was volume-assisted-controlled. Most of the patients were pronated, averaging 12h a day for two days.

In a Mexican observational study, the use of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) was reported in 100% of the patients admitted to the ICU, this support was given for 11 days (median), about half of the patients were placed in prone position.15 In the SATICOVID study, the median IMV was 13 days.16 In both Latin American studies, the duration of invasive ventilation was longer than that found by us. In the multicenter study PRo-VENT-COVID, the volume-controlled mode was much lower than that found by us (19% vs. 90%), the most used ventilatory mode was pressure-control ventilation (52%) and Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (SIMV) in 7% of cases. Regarding the prone position, they reported its use in 25% of all patients and in 60% of patients with Pa/FiO2<150, for a time of 8h on average, which is below what was found in our study.25

The organic dysfunction evaluated from prognostic scores such as SOFA or APACHE II has been associated with the severity of patients with COVID-19; in our study, we found an average of 7 points, which is higher than that found in other studies of our region15,16 and in North American,26 European27 and Asian studies.28

Mortality in our study was 60%, this is slightly higher compared to that reported in patients hospitalized in ICU in Argentina (57%) and Mexico (52%),15,16 nevertheless, was higher than that reported in Canada (26%),29 30% in the United States of America,26 Denmark (35–51%, depending on the weeks of ICU hospitalization),27 29% in London.19 This is possibly explained by the severity of the pulmonary involvement, most of the patients in our study showed a phenotype of high pulmonary elastance (phenotype H) and by the difference in the resources available to support very critical cases (e.g.: ECMO) between developed countries and some of the countries of our region.30

Markers of severity and risk of mortality such as C-reactive protein, LDH, ferritin, advanced age, obesity, and kidney failure were like other studies.13,15,16,19,31 In the ventilatory aspect, patients with phenotype H, with higher PEEP, FiO2 requirements and the need for pronation had a higher risk of mortality. From the above, we can interpret that the more severe the disease, the greater the risk of dying, therefore, these patients require a higher level of support.

Our work presents some important limitations, it is an observational study, of a single center, that although it was the largest hospitalization center for critical cases of COVID-19 in our region during the first year of the pandemic, this limits its generalizability.

ConclusionsCOVID-19 is a disease with high morbidity and mortality, in our study, we found that a higher level of inflammation, impaired lung compliance, severe oxygenation disorder and the need for greater ventilatory support related to a higher risk of fatal outcome.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.